Abstract

Background

Despite high rates of intimate partner violence in South Africa, there have been no national studies of men's perpetration of violence against female partners.

Methods

We analyzed data from the South Africa Stress and Health Study, a cross-sectional, nationally representative study, specifically examining data for men who had ever been married or had ever cohabited with a female partner. We calculated the prevalence of physical violence against intimate female partners and used logistic regression to examine associations with physical abuse during childhood and exposure to parental and community violence.

Results

A total of 834 male participants in the South Africa Stress and Health Study met the study criteria. Of these, 27.5% reported using physical violence against their current or most recent female partner during their current or most recent marriage or cohabiting relationship. Crude odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) indicated significant associations between perpetration of violence against an intimate partner and witnessing parental violence (OR 3.91, 95% CI 2.66–5.73) or experiencing physical abuse during childhood (OR 3.24, 95% CI 2.27–4.63), but not exposure to community violence (OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.88–1.88). The 2 significant associations persisted in adjusted analyses: OR 3.22 (95% CI 1.94–5.33) for witnessing parental violence and OR 1.73 (95% CI 1.07–2.79) for experiencing physical abuse during childhood.

Interpretation

We found a high prevalence of physical violence perpetrated by men against their intimate partners. Men who experienced physical abuse during childhood or were exposed to parental violence were at the greatest risk.

Most research about men's perpetration of violence against female intimate partners has concentrated on elucidating the factors that put women at risk for experiencing such violence and identifying the related service needs. Less work has been done to investigate the factors affecting men's risk of perpetrating violence against women. Such work is needed to inform development of empirically based public health programs to reduce men's use of such violence. Intimate partner violence is of pandemic proportions, with global estimates indicating that 15% to 75% of women have experienced such abuse.1,2 Such violence may confer grave health consequences, including transmission of HIV/AIDS.3

The overwhelming majority of research on violence against intimate partners perpetrated by men has been conducted in Western countries, with the focus on men at high risk for such activity (e.g., prisoners, people enrolled in intervention programs for batterers).4,5 This work has highlighted the importance of exposure to violence early in life (e.g., witnessing parental violence, experiencing child abuse) in predicting perpetration of violence against a partner during adulthood.6 Recently, the potential relations between community violence and men's perpetration of violence against intimate partners have also been examined.7

Fewer studies have been done in developing nations, but several notable investigations have recently assessed men's perpetration of violence against intimate partners in South Africa, specifically in Eastern Cape and Cape Town. Two of these studies have indicated high rates of violence against intimate partners: 31.8% in Eastern Cape8 and 42.3% in Cape Town.9 The extent to which these findings reflect national rates is unknown. Furthermore, work with both men and women in South Africa has demonstrated strong relations between violence (men's perpetration and women's victimization) and higher rates of sexually risky behaviours.3,8 Associations between women's experience as victims of intimate partner violence and HIV infection have also been documented.3 These data strongly suggest that men's perpetration of violence against intimate partners is common in South Africa and that it may play an important role in this nation's HIV epidemic,3,8 which currently ranks highest in the world with respect to the number of people living with HIV.10

In the study reported here, we sought to build upon prior work by using a national sample of South African men to examine the prevalence of physical violence perpetrated by men against their female intimate partners and potential violence-related risk factors (i.e., exposure to parental violence, experience of abuse in childhood and exposure to community violence).

Methods

Study participants and data collection

For this study, we used data from the South Africa Stress and Health Study,11 a national investigation examining the prevalence and correlates of mental health concerns. The main study involved a 3-stage area probability sample of adults (at least 18 years old) living in households and hospital-based hostels; residents of military barracks and prisons were excluded. In stage 1, the study team developed area-based sampling frames from enumeration area maps. They divided the 85 783 geographic enumeration areas into 53 strata based on province, urbanicity and racial group. They then selected 960 enumeration areas and used the 2001 South African census to develop listings of homes and dwelling units within each enumeration area, identifying a random sample of 5 homes or dwelling units in each selected enumeration area. Fieldwork supervisors and interviewers contacted each household or dwelling unit and obtained informed consent to participate in the survey from a single adult respondent, who was randomly selected using the Kish procedure.12

For the current study, we applied the following inclusion criteria: report of ever having been married or in a cohabiting relationship, response to the survey question about perpetration of physical violence against an intimate partner and response regarding all 3 primary exposures (witnessing parental violence, experiencing physical abuse during childhood and exposure to community violence).

All of the research protocols for the South Africa Stress and Health Study were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the University of Michigan and Harvard Medical School. A single-project assurance of compliance obtained from the Medical University of South Africa was approved by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Survey development and administration

Interviewers trained in field research methods and in the administration of the paper-and-pencil version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview used by the World Mental Health Survey Initiative13 administered the surveys in person during prescheduled appointments in January 2002 and August 2004. The questionnaire was available in 6 languages (English, Afrikaans, Zulu, Xhosa, Northern Sotho and Tswana). To ensure consistency of constructs across languages, the survey developers translated the non-English versions of the questionnaire into English and then back-translated these translations into each South African language; they also conducted 2 formal pretests with 50 participants each.

Definition of key variables

We collected respondents' information for the variables of interest via self-reporting. We assessed demographic variables (age, family income, education, marital status, employment, number of biological children), variables related to exposure to violence during childhood (witnessing parental violence, experiencing physical abuse) and perpetration of physical violence against an intimate partner using items from the World Mental Health Survey, an instrument used in more than 25 countries and in all World Health Organization (WHO) regions (Box 1).13 We dichotomized responses regarding exposure to parental violence and childhood abuse and perpetration of violence against an intimate partner as ever versus never. We measured exposure to community violence using a single item from the National Survey of American Life14 (Box 1) and coded responses as ever versus almost never or never.

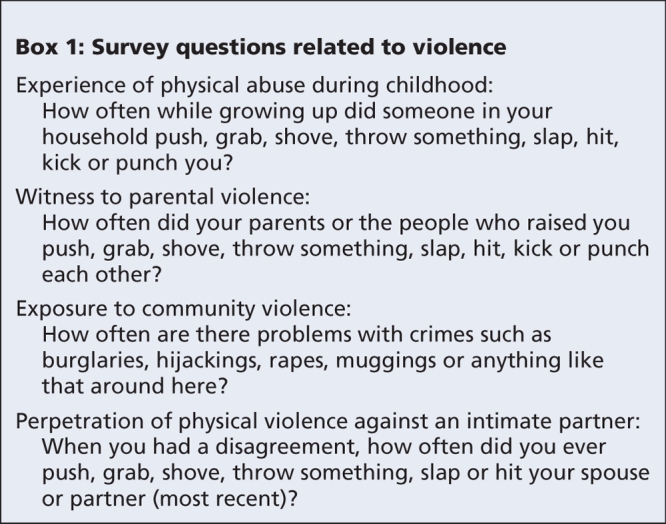

Box 1.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and other characteristics are expressed as percentages weighted according to the 2001 South African Census. We estimated the prevalence of physical violence against an intimate partner in the most recent marriage or cohabiting relationship. We used simple logistic regression to assess bivariate demographic differences in the perpetration of physical violence against an intimate partner (with significance set at p < 0.05). We used χ2 analysis to assess such differences across the South African provinces. We then constructed a multivariable logistic regression model, with adjustment for all of the demographic characteristics that were considered, to examine the associations between perpetration of physical violence against an intimate partner and the 3 variables related to previous exposure to violence: witnessing parental violence, experiencing physical abuse during childhood and exposure to community violence. Following the rationale described by Miettinen and Cook,15 we included demographic variables that have been proposed or identified as correlates of violence against intimate partners in the multivariable model as covariates; these demographic variables were simultaneously entered into the adjusted model. To preserve statistical power and reduce the bias that may result from list-wise deletion, we conducted multiple imputation of the exposure variables and demographic covariates. More specifically, we used a bootstrapping-based, expectation-maximizing algorithm to impute missing values.16 We did not impute outcome values, because χ2 analyses revealed no differences at the p < 0.05 level in terms of demographic characteristics and exposures of interest between men who reported perpetration of violence against intimate partners and those who did not. Because of the complex survey design, we used the Taylor series linearization method to take the weighting and clustering into account using STATA, version 9.

Results

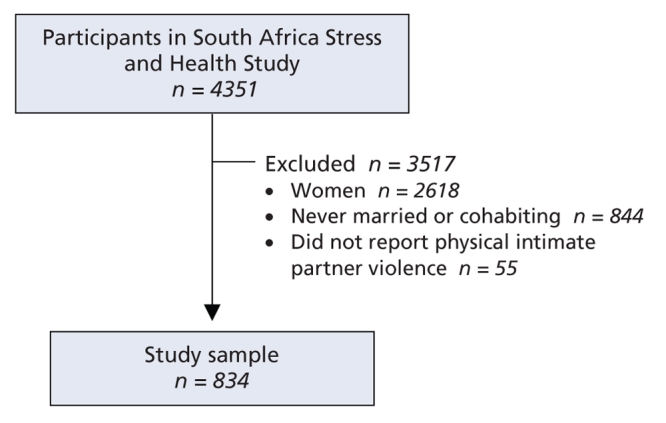

Of the 5088 adults selected for the South Africa Stress and Health Study, 4351 agreed to participate (85.5% response rate), of whom 1733 (39.8%) were men (Figure 1). In total, 889 men (20.4% of the total sample; 51.3% of the male respondents) reported ever have been married or in a cohabiting relationship. Of these, 55 (6.2%) did not provide outcome information and were excluded from the analysis reported here. The final sample for the current study was therefore 834.

Figure 1: Flow diagram showing study population of South African men who had ever been married or in a cohabiting relationship and who provided data regarding exposure to violence and their own perpetration of physical violence against intimate partners.

Demographic characteristics

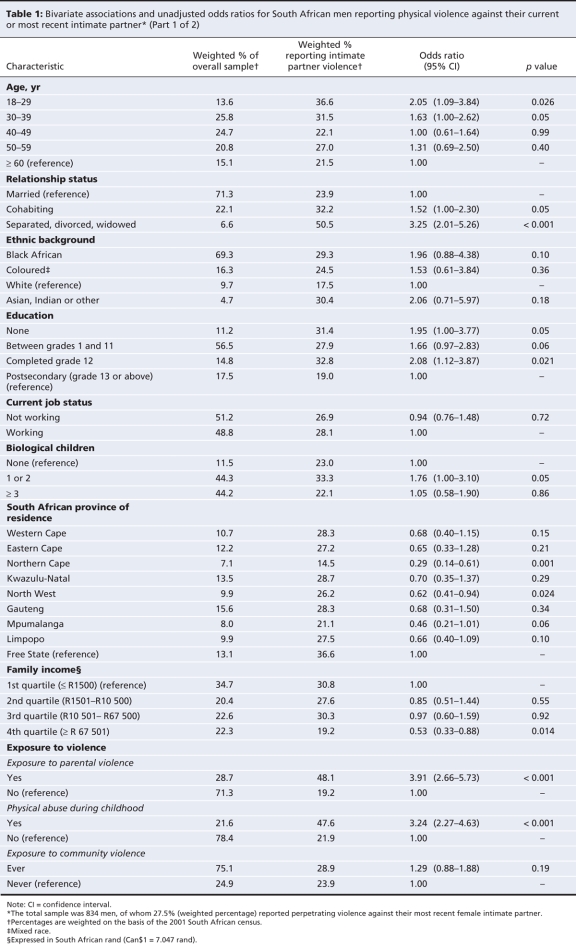

The mean age of the 834 respondents included in the current analysis was 43.8 years. Most of the men (71.3%) were married, and most (69.3%) were black Africans (Table 1). Slightly more than half of the respondents (56.5%) reported their educational attainment as between grades 1 and 11, and a similar percentage (51.2%) reported being unemployed at the time of the study. Slightly more than one-third of the men (34.7%) reported an annual family income up to 1500 South African Rand (equivalent to about Can$212 in mid-2008). Most of the men (88.5%) reported having at least one biological child.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics and violence against intimate partners

Among the 834 respondents included in the study, 27.5% reported having used physical violence against their female partners in the most recent marriage or cohabiting relationship (Table 1). Younger men (18–29 years of age) were significantly more likely to have perpetrated physical violence against an intimate partner than men 60 years of age and older (crude odds ratio [OR] 2.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.09–3.84; p = 0.026). No significant differences were apparent for other age groups. Men who were separated, divorced or widowed were more than 3 times as likely as married men to report violence against their intimate partners (OR 3.25, 95% CI 2.01–5.26; p < 0.001). Men who had completed grade 12 were at greater risk than men with postsecondary education (OR 2.08, 95% CI 1.12–3.87; p = 0.021). Compared with men from Free State province, men from Northern Cape province (OR 0.29, 95% CI 0.14–0.61; p = 0.001) and North West province (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.41–0.94; p = 0.024) were less likely to report violence against their intimate partners. We identified no significant differences based on ethnic background, family income or number of biological children.

Exposure to violence and violence against intimate partners

Rates of exposure to violence were high (Table 1). More than 1 in 4 respondents (28.7%) reported exposure to parental violence during childhood, and more than 1 in 5 respondents (21.6%) reported having been physically abused as a child. A majority of the men (75.1%) reported current exposure to violence in their communities.

Men who reported witnessing parental violence were almost 4 times as likely as men who had not witnessed such violence to report violence against their intimate partners (crude OR 3.91, 95% CI 2.66–5.73; p < 0.001). The risk of perpetrating physical violence against intimate partners was similarly elevated among men who reported experiencing abuse as a child (crude OR 3.24, 95% CI 2.27–4.63; p < 0.001). No significant relation was observed between physical violence against intimate partners and exposure to community violence; this variable was therefore excluded from further analyses.

Adjusted analysis predicting violence against intimate partners

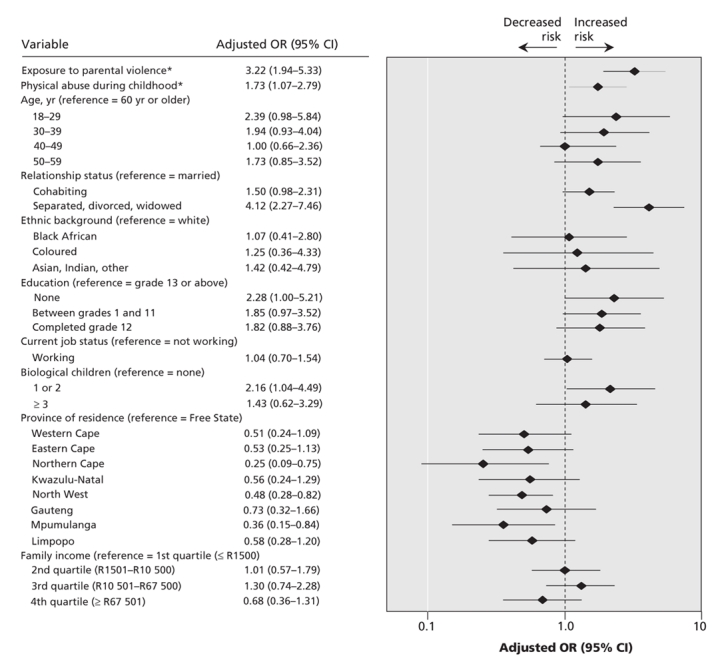

In the adjusted analyses, exposure to parental violence (adjusted OR 3.22, 95% CI 1.94–5.33; p < 0.001) and experience of physical abuse as a child (adjusted OR 1.73, 95% CI 1.07–2.79; p = 0.027) remained significantly related to men's perpetration of physical violence against their intimate partners (Figure 2). Other significant correlates were being separated, divorced or widowed (adjusted OR 4.12, 95% CI 2.27–7.46, p < 0.001), having 1 or 2 biological children versus having no children (adjusted OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.04–4.49; p = 0.039) and being from Mpumalanga province (adjusted OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.15–0.84; p = 0.018), Northern Cape province (adjusted OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.09–0.75; p = 0.014) or North West province (adjusted OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.28–0.82; p = 0.08) relative to being from Free State province.

Figure 2: Adjusted odds ratios for reported use of physical violence against intimate partners according to exposure to other types of violence for 834 South African men. *Primary outcome. CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

Interpretation

Among this national sample of South African men, more than one-quarter of respondents (27.5%) reported having perpetrated physical violence against their most recent female partner. This finding falls within the range of estimates documented in other samples of South African men (22.9%–42.3%)8,9 and the few investigations of men's perpetration of violence against intimate partners in other developing nations (18%–75%).2,17

Our estimates might have been higher if lifetime perpetration of violence against all intimate partners, rather than violence against the most recent partner, had been assessed. Similarly, estimates might have been higher if younger men without a history of marriage or cohabitation had been included. Such considerations may be particularly important in South Africa, where multiple partnering has been associated with men's perpetration of violence against intimate partners.18 Furthermore, existing studies that have examined men's perpetration of violence against intimate partners in South Africa have included sexual violence,8,18 which has allowed a wider range of abusive behaviours to be reported. Although these variations limit direct comparisons between studies, the current findings support the perception that men's perpetration of violence against intimate partners is pervasive in South Africa. Coordinated global data collection, such as the WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence,1 is needed to both examine this issue and increase the potential for comparisons between countries.

In this work we documented provincial differences in perpetration of physical violence against intimate partners, with residents of Mpumalanga, Northern Cape and North West provinces being less likely to report such violence than men from Free State province. More work is needed to understand the social, economic and cultural factors that may account for this observation. Also noteworthy was the association between having 1 or 2 biological children (but not a greater number of children) and perpetration of violence. Research is needed to elucidate why having a small number of children may heighten a man's likelihood of violence against his partner; for example, there may be factors related to newer parenthood. Notably, although separated, divorced and widowed men were significantly more likely than married men to report perpetration of physical violence against their intimate partners, the reported perpetration of violence was still relatively high (23.9%) among married South African men. Thus, efforts to combat violence against intimate partners should include men across all relationship categories, given that previous research has shown that such violence is perpetrated against both current and former partners.19

Echoing prior work in South Africa,18,20 South Asia21,22 and the United States,6,23 we found that exposure to parental violence during childhood was a significant predictor of physical violence against intimate partners. Men who witnessed parental violence may come to view such behaviour as normative.9,20,24 Furthermore, men who have witnessed violence against their mothers may develop traditional attitudes favouring men's domination over women, which has also been associated with violence against female intimate partners.25

Consistent with work in the United States and South Africa, men who experienced physical abuse in childhood were more likely than men who had not been abused to report perpetration of physical violence against their intimate partners.6 However, in one South African study, this relation ceased to be significant when variables concerning the partner and relationship conflict (e.g., suspicion of infidelity, partner's refusal to have sex) were considered;9 these findings indicate that social norms promoting men's sexual entitlement over female partners may be an even stronger predictor of their propensity for violence against intimate partners.

In contrast to work conducted with adolescents in the United States,7 we found that exposure to community violence was not significantly associated with men's perpetration of physical violence against their intimate partners. The lack of variation in the current sample (i.e., over 75% of respondents reported exposure to community violence) may explain the present finding. The high rate of self-reported exposure to community violence is not surprising, given the extremely high levels of violent crime documented in South Africa.26 The high prevalence of exposure to community violence may also stem from the possibility that participants in our study reported exposure to media coverage of violence as exposure to community violence. Another important consideration is the potential differential effect of direct (i.e., personal) involvement in community violence versus witnessing community violence. Prior work with South African men has revealed strong relations between involvement in community violence and perpetration of violence against intimate partners.18 Such differences in assessment complicate comparisons between studies in this area. Moreover, South Africa has a history of politically motivated violence related to apartheid, and a link has previously been established between exposure to political violence and perpetration of violence against intimate partners.27 As such, extreme forms of community-level violence (e.g., torture) may be more predictive of men's violent behaviours in the context of this nation.

Future investigations should seek to identify the factors that promote resilience among men who have had adverse childhood experiences. To date, only a few studies have examined the factors that may prevent men from perpetrating violence against their intimate partners (e.g., family connectedness28).

Beyond the limitations associated with assessing violence perpetrated against current intimate partners only, as described earlier, the current study had limitations in terms of assessing exposure to violence. Specifically, the current data do not include information on the age at which exposure to physical violence occurred during childhood or the identity of perpetrators of child abuse, data that might allow greater precision in assessing the risk of perpetrating violence against intimate partners in adulthood. Other limitations include the cross-sectional design, which invokes temporality concerns (i.e., whether the exposures preceded the outcome), although we did examine 2 exposures that occurred during childhood. This study assessed self-reported perpetration of physical violence against intimate partners, which may be subject to under-reporting. However, the instrument used for data collection assessed multiple behaviourally specific forms of physical violence based on modified items from the Conflict-Tactics Scale,29 which has been validated internationally.30

We hope that the findings of the current study, along with the growing body of work from South Africa addressing men's perpetration of violence against their partners, will motivate additional research, particularly longitudinal studies, to both investigate additional context-specific risk factors (e.g., politically motivated violence) and identify protective factors. In light of accumulating evidence linking men's violence against intimate partners with their controlling and sexually risky behaviours (e.g., transactional sex,8 multiple partnering8 and inconsistent use of condoms31), preventing violence against intimate partners may help to alter the course of South Africa's HIV epidemic.32 Such initiatives should therefore be considered a public health priority. Furthermore, the social structure now present in South Africa, which is characterized by extremes in wealth and other social determinants, can also be observed in other developing countries, such as India, and violence against intimate partners has been highlighted as an important factor driving social disparities in health in these contexts.33 Therefore, the high prevalence of violence against intimate partners may also be an important consideration in efforts to reduce health disparities across South Africa and in other developing nations.

@@ See related commentary by Campbell and colleagues, page 511

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The South African Stress and Health Study was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. We thank the staff of the World Mental Health Survey for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork and data analysis. These activities of the World Mental Health Survey Initiative were supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (grant R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (grants R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864 and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (grant FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan-American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The South Africa Stress and Health Study was funded by grant R01-MH059575 from the US National Institute of Mental Health and the US National Institute on Drug Abuse, with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. Dr. Gupta's work was partially supported by award T32MH020031 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Institutes of Health. A complete list of publications related to the World Mental Health Survey Initiative can be found at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/.

Footnotes

Une version française de ce résumé est disponible à l'adresse www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/179/6/535/DC1

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Jhumka Gupta led the conception, statistical analysis, interpretation of data and writing of the study presented here. All other authors contributed to the study conception, interpretation of findings and critical revision of the manuscript. All of the authors approved this version of the manuscript. David R. Williams is the principal investigator of the South Africa Stress and Health Study, from which the data analyzed here were obtained.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Jhumka Gupta, Department of Society, Human Development, and Health, Harvard School of Public Health, 677 Huntington Ave., Rm. 705, Boston MA 02115, USA; fax: 617 432-3123; jgupta@hsph.harvard.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006;368:1260-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Silverman JG, Gupta J, Decker MR, et al. Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi women. BJOG 2007;114:1246-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, et al. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet 2004;363:1415-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Rothman EF, Gupta J, Pavlos C, et al. Batterer intervention program enrollment and completion among immigrant men in Massachusetts. Violence Against Women 2007;13:527-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Swogger MT, Walsh Z, Kosson DS. Domestic violence and psychopathic traits: distinguishing the antisocial batterer from other antisocial offenders. Aggress Behav 2007;33:253-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, et al. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: a 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71:741-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Malik S, Sorenson SB, Aneshensel CS. Community and dating violence perpetration among adolescents: perpetration and victimization. J Adolesc Health 1997;21:291-302. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Nduna M, et al. Perpetration of partner violence and HIV risk behaviour among young men in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS 2006;20:2107-14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Laubscher R, et al. Intimate partner violence: prevalence and risk factors for men in Cape Town, South Africa. Violence Vict 2006;21:247-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS). South Africa: Country situation analysis. Pretoria (South Africa): UNAIDS; 2006. Available: http://www.unaidsrstesa.org/country_profiles/2007/South%20Africa250107.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 7).

- 11.Williams DR, Herman A, Kessler RC, et al. The South Africa Stress and Health Study: rationale and design. Metab Brain Dis 2004;19:135-47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Kish L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. J Am Stat Assoc 1949;44:380-7.

- 13.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004;13:93-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, et al. The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004;13:196-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Miettinen OS, Cook EF. Confounding: essence and detection. Am J Epidemiol 1981;114:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Horton NJ, Kleinman KP. Much ado about nothing: a comparison of missing data methods and software to fit incomplete data regression models. Am Stat 2007;61: 79-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Martin SL, Tsui A, Maitra K, et al. Domestic violence in Northern India. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150:417-26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Hoffman M, et al. Sexual violence against intimate partners in Cape Town: prevalence and risk factors reported by men. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:330-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Kyriacou DN, Anglin D, Taliaferro E, et al. Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence against women. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1892-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Abrahams N, Jewkes R. Effects of South African men's having witnessed abuse of their mothers during childhood on their levels of violence in adulthood. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1811-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Martin SL, Moracco KE, Garro J, et al. Domestic violence across generations: findings from Northern India. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:560-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, et al. Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. Am J Public Health 2006;96:132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Oriel KA, Fleming MF. Screening men for partner violence in a primary care setting: a new strategy for detecting domestic violence. J Fam Pract 1998;46:493-8. [PubMed]

- 24.Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. Lancet 2002;359:1423-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:1603-17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for Southern Africa. South Africa: country profile on drugs and crime. Pretoria (South Africa): The Office; 2002. Available: www.unodc.org/pdf/southafrica/country_profile_southafrica.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 3).

- 27.Gupta J, Acevedo-Garcia D, Hemenway D, et al. Pre-migration political violence exposure associated with intimate partner violence perpetration among a community-based sample of immigrant men. Am J Public Health DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2007.120634 Epub 2008 Aug 13 ahead of print.

- 28.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum BW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA 1997;278:823-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, et al. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2). J Fam Issues 1996;17:283-316.

- 30.Straus MA. Cross-cultural reliability and validity of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales: a study of university student dating couples in 17 nations. Cross-Cultural Res 2004;38:407-32.

- 31.Raj A, Santana MC, La Marche A, et al. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1873-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Dunkle KL, Jewkes R. Effective HIV prevention requires gender-transformative work with men. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Subramanian SV, Ackerson LK, Subramanyam MA, et al. Domestic violence is associated with adult and childhood asthma prevalence in India. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:569-79. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.