Abstract

This experiment examined relationships among adulthood victimization, sexual assertiveness, alcohol intoxication, and sexual risk-taking in female social drinkers (N = 161). Women completed measures of sexual assault and intimate partner violence history and sexual assertiveness before random assignment to 1 of 4 beverage conditions: control, placebo, low dose (.04%), or high dose (.08%). After drinking, women read a second-person story involving a sexual encounter with a new partner. As protagonist of the story, each woman rated her likelihood of condom insistence and unprotected sex. Victimization history and self-reported sexual assertiveness were negatively related. The less sexually assertive a woman was, the less she intended to insist on condom use, regardless of intoxication. By reducing the perceived health consequences of unprotected sex, intoxication indirectly decreased condom insistence and increased unprotected sex. Findings extend previous work by elucidating possible mechanisms of the relationship between alcohol and unprotected sex – perceived health consequences and situational condom insistence – and support the value of sexual assertiveness training to enhance condom insistence, especially since the latter relationship was robust to intoxication.

Keywords: alcohol, sexual risk-taking, sexual assertiveness, condom use, sexual assault, intimate partner violence

Heterosexual contact is by far the predominant mode of HIV infection for women, accounting for 80% of new infections (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). Because the risk of heterosexual transmission of HIV can be greatly reduced through consistent use of latex condoms (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2006), a major focus of HIV-prevention efforts directed toward heterosexual women has been to strengthen sexual assertiveness, particularly condom negotiation and refusal of unprotected sex (Sikkema et al., 1995; Weinhardt et al., 1998). Survey research has suggested that higher sexual assertiveness is associated with lower sexual risk behavior (Noar, Morokoff, & Redding, 2002; Zamboni, Crawford, & Williams, 2000; Somlai et al., 1998), which suggests that women with sexual assertiveness skills routinely use these skills to protect themselves in sexual situations. However, little is known about under what conditions sexually assertive women enact these skills. For example, many sexual situations involve alcohol consumption (Goldstein, Barnett, Pedlow, & Murphy, 2007), yet it is unclear how women’s intoxication affects their insistence on condom use with a new sex partner. The present study conducted an experiment to address this knowledge gap. Because women who have a history of victimization tend to have lower sexual assertiveness (Rickert, Sanghvi, & Wiemann, 2002) and elevated risk factors for sexually transmitted diseases (Koenig, Doll, O’Leary, & Pequegnat, 2004), we also examined the influence of a history of victimization.

Alcohol Intoxication and Condom Use

A large number of studies have found a relationship between alcohol use and sexual risk-taking, particularly nonuse of condoms (Cooper, 2002). Most studies finding such a relationship have used survey methodologies assessing the global association between these variables. For example, in one study, level of alcohol consumption was found to be correlated with inconsistent condom use in HIV-infected injection drug users with a history of alcohol problems, and inconsistent condom use was more common for women than for men, statistically controlling for possible confounds (Ehrenstein, Horton, & Samet, 2004). Such findings imply that, due to the effects of alcohol, individuals are less likely to use condoms when they are intoxicated. However, studies examining specific events using diaries or other self-report methodologies have failed to show a relationship (e.g., Morrison et al., 2003). In recognition of this inconsistency, Cooper (2006) asserted that “future research should focus on delineating the conditions under which, and the individuals for whom, different causal (and noncausal) processes are most likely to operate” (p. 22). Because it allows tight control over the conditions under study and close examination of putative causal processes, research using the experimental method is particularly well-suited to answer such a call.

Results from laboratory-based alcohol-administration experiments have suggested that acute alcohol intoxication promotes sexual risk-taking in a number of ways. Maisto and colleagues (2002, 2004) found that perceived intoxication predicted decrements in women’s verbally assertive responses to a man’s suggestion for unprotected sex. Alcohol has also been shown to increase negative condom attitudes (Gordon, Carey, & Carey, 1997), increase perceived ability to discern a potential partner’s HIV status (Monahan, Murphy, & Miller, 1999), decrease individuals’ perceptions of sexual risk and negative consequences of risk behavior (Fromme, D’Amico, & Katz, 1999), and increase intentions to engage in risky sex (Abbey, Saenz, & Buck, 2005; MacDonald, MacDonald, Zanna, & Fong, 2000). While each of these studies has examined alcohol’s effects on important aspects of sexual decision-making, more research is needed to specify how alcohol affects multiple aspects in the moment as the sexual decision-making process unfolds. For example, perceptions of sexual risk might mediate the effects of alcohol on risky sex intentions. The present study examined this hypothesis using a hypothetical scenario. In addition, we examined intentions to insist on condom use as an additional mediator in the sexual decision-making process.

Sexual Assertiveness and Condom Insistence

Morokoff et al. (1997) conceptualized sexual assertiveness as the strategies women use to safeguard their sexual autonomy. These strategies encompass three areas: initiation of wanted sexual events; refusal of unwanted sex; and prevention of unwanted pregnancy and STDs. A woman’s previous experience being sexually assertive should predict her likelihood of insisting on using a condom in a sexual encounter with a man. In this study we examined the relationship between the background trait of sexual assertiveness and its situational enactment.

The Influence of Adult Victimization

Women’s experiences of victimization in adulthood, including adult sexual assault (ASA) and intimate partner violence (IPV), have been independently associated with higher alcohol use (Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2005; Kaysen et al., 2007), lower general assertiveness (Rickert et al., 2002; Rosenbaum & O’Leary, 1981), and higher HIV/STD risk (Newcomb & Carmona, 2004; Gielen et al., 2007). He et al. (1998) found that women who had been raped or threatened with assault were more likely to have multiple partners and to engage in unprotected sex than women without such experiences. Littleton et al. (2007) found that a history of physical abuse by a romantic partner was associated with an increased likelihood of both having sex after drinking alcohol and having multiple sexual partners in the past year. Collins et al. (2005) found that, among the women in their sample, concurrent substance use and prior adult victimization (including sexual, physical, and theft victimization) together predicted 25% of the variance in number of sex partners and 26% of the variance in high risk sex. Moreover, Corbin et al. (2001) found that, in their sample of college women, severe sexual victimization, defined as having experienced attempted or completed rape, was associated with lower sexual refusal assertiveness, higher weekly alcohol consumption, greater positive outcome expectancies for alcohol consumption, more sexual activity subsequent to alcohol consumption, and more consensual sexual partners. Such findings point to the importance of understanding the nexus of prior victimization in adulthood, substance use, sexual assertiveness, and sexual risk. In the present study, we explored this nexus in a tightly controlled experimental setting.

The Present Study

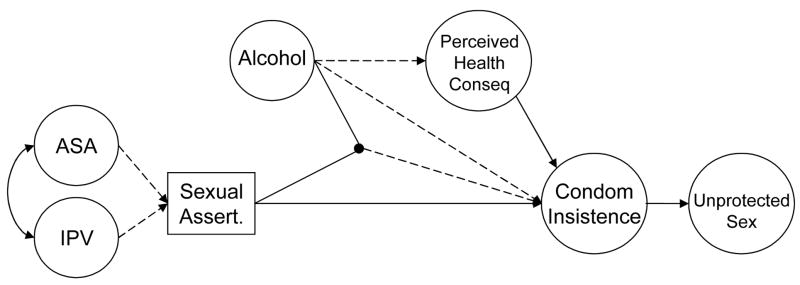

The present study sought to extend previous work by examining relationships among history of adult victimization, sexual assertiveness, and risky sexual decision-making in the context of acute alcohol intoxication. Four conditions were tested: A low dose and a high dose of alcohol (target peak blood alcohol concentrations of .04% and .08%, respectively), placebo, and control. The interaction of alcohol condition with background sexual assertiveness was also investigated. The hypothesized model is shown in Figure 1. We hypothesized that general sexual assertiveness would mediate the effects of past adult victimization on condom insistence in the experimental situation, which in turn would mediate the effects of general sexual assertiveness on intentions to engage in unprotected sex in the situation. With regard to alcohol, we hypothesized that intoxication would interfere with the situational enactment of sexual assertiveness in the form of condom insistence, except among women with low general sexual assertiveness, in whom we expected low condom insistence regardless of intoxication. Furthermore, because intoxication has been shown to decrease individuals’ perceptions of sexual risk and negative consequences of risk behavior (Fromme et al., 1999), we expected that perceived health consequences would mediate the effect of alcohol on condom insistence, which in turn would mediate the effect of perceived health consequences on intentions to engage in unprotected sex. To reflect the multiple ways that alcohol influences individuals in their typical drinking contexts the present study considered alcohol consumption as a multidimensional phenomenon. Thus, in our structural equation model alcohol intoxication is a latent variable composed of three indicators: dose, expectancy set, and perceived intoxication.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model. Solid lines represent hypothesized positive relationships whereas dashed lines represent hypothesized negative relationships.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from a large urban community in the Pacific Northwest through ads in local newspapers and flyers seeking single female social drinkers between the ages of 21 and 35 to participate in a study on social interactions between men and women. The sample consisted of 161 women with a mean age of 25.02 (SD = 3.85). Sixty-five percent self-identified as Caucasian/White, 14.3% as African American, 12.4% as multiracial, 2.5% as Asian American/Pacific Islander, and 6.2% as “other”. Overall, 10.6% self-identified as Hispanic or Latina, 36.6% as unemployed, 33.5% as employed full-time, 34.2% as students (full- or part-time), and 71.5% as earning less than $21,000 a year.

Callers were screened to ensure that they had no medical conditions or medication usage that would contraindicate alcohol consumption and no history of problem drinking. Those who drank fewer than one or more than forty drinks per week were excluded. The mean drinks per week reported was 10.19 (SD = 7.83). To ensure that all participants would find the experimental story relevant to their current dating status and lifestyle, callers were excluded if they were in a committed, exclusive relationship, had no interest in relationships with men, or had never had consensual vaginal sex with a man. Eligible callers were scheduled for the study and instructed not to drive to the lab nor to eat or drink caloric beverages for the preceding three hours.

Procedure

Overview

All procedures and materials were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the University of Washington. Each participant was conducted through the one-session protocol individually by a female experimenter and completed all background questionnaires and dependent measures in private via computer. The experimenter checked her photo identification, verified her age, and administered a breathalyzer (Alco-Sensor IV, Intoximeters, Inc.) to ensure that her pre-experimental blood alcohol level (BAL) was at .00%. The experimenter then obtained informed consent. After completing the background measures, the participant received a beverage (see below) and began the experimental protocol in which she read and responded to a stimulus story (see below) designed to assess sexual decision-making processes. Afterwards, those who had received alcohol remained in a comfortable room until their BALs fell below .03%. Immediately prior to discharge, participants were fully debriefed, compensated $10–15 per hour1 for their time, and given resource materials on STDs and HIV.

Beverage administration

Participants were randomly assigned to one of 5 experimental conditions: low dose alcohol (0.82 ml vodka in 3.4 ml orange juice per kg body weight), high dose alcohol (1.75 ml vodka in 7.0 ml orange juice/kg), placebo (0.82 ml bogus vodka in 3.4 ml orange juice/kg), low dose control (4.2 ml orange juice/kg) or high dose control (8.7 ml orange juice/kg).2 The low dose was chosen to reach a target peak BAL of .04%, the high dose .08%.

In the alcohol conditions, participants were breathalyzed every 2 to 5 minutes until they reached a criterion BAL of .025 (low dose) or .055 (high dose). These criterion BALs were selected to ensure that participants began reading the story while their BALs were ascending toward the target. Each alcohol participant had a control participant “yoked” to her to control for individual variation in time to criterion BAL.3 The experimenter breathalyzed the placebo participant at the same time point at which her yoked alcohol participant had reached the criterion BAL. The experimenter told the placebo participant she was right on target with a BAL of .027 and rising, and the participant started reading the story at the same time point as the alcohol participant to whom she had been yoked.4 Final cell sizes were as follows: low dose alcohol n = 32, low dose control n = 32, placebo n = 33, high dose alcohol n = 32, and high dose control n = 32.

Materials and Measures

Background measures

A 20-item Sexual Victimization Scale (Testa, 2001; cf. Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, Livingston, & Koss, 2004; cf. Koss & Oros, 1982) was used to measure adult sexual assault (ASA). Participants were instructed to indicate how many times various experiences had occurred in their lifetimes since the age of 14. Experiences were grouped according to the tactic used by the perpetrator to gain sexual gratification. Responses were rated on 4-point Likert scales ranging from 0 = 0 times to 3 = 3 or more times. Cronbach’s alpha for all twenty items was .90. Four subscales were derived: sexual coercion (alpha = .84, sexual assault not meeting the legal definition for rape (alpha = .65), attempted rape (alpha = .71), and completed rape (alpha = .83). Averages were computed for each group of items and used as indicators of ASA. Means and intercorrelations are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Measured Variables

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Achieved BAL | --- | --- | --- | ||||||

| 2. Perceived Intoxication | --- | --- | .72** | --- | |||||

| 3. Expected Alcohol Amount | --- | --- | .83** | .78** | --- | ||||

| 4. Past Sexual Coercion | 4.46 | 4.27 | −.06 | .00 | −.09 | --- | |||

| 5. Past Sexual Assault | 2.23 | 2.36 | .00 | −.02 | −.07 | .54** | --- | ||

| 6. Past Attempted Rape | 1.01 | 1.79 | −.10 | .03 | −.08 | .46** | .75** | --- | |

| 7. Past Rape | 1.69 | 3.19 | −.02 | .05 | −.05 | .50** | .67** | .69** | --- |

| 8. IPV - Indirect | 1.80 | 0.83 | −.07 | −.11 | −.13 | .38** | .42** | .37** | .33** |

| 9. IPV - Direct | 1.58 | 0.71 | −.15 | −.14 | −.27** | .41** | .40** | .35** | .40** |

| 10. IPV - Severe | 1.18 | 0.46 | −.13 | −.18* | −.21** | .23** | .34** | .37** | .37** |

| 11. Sexual Assertiveness | 4.04 | 0.68 | −.06 | −.10 | .00 | −.33** | −.26** | −.23** | −.26** |

| 12. Direct Request | 4.93 | 1.45 | −.11 | −.10 | −.07 | −.03 | −.15 | −.08 | −.12 |

| 13. Withholding Sex | 4.78 | 1.70 | −.10 | −.16 | −.08 | .02 | −.04 | −.02 | −.02 |

| 14. Risk Information | 3.65 | 2.11 | .00 | −.11 | −.06 | −.04 | −.04 | .02 | .00 |

| 15. Likelihood of Unprotected Sex | 1.84 | 1.79 | .13 | .15 | .09 | .08 | .21** | .19* | .14 |

| 16. Encouraging Behaviors | 1.69 | 1.39 | .16* | .20* | .10 | .01 | .14 | .11 | .16 |

| 17. Discouraging Behaviors | 2.85 | 1.42 | −.03 | .05 | .04 | .03 | −.03 | .06 | .02 |

| 18. Likelihood of STD | 3.12 | 1.38 | −.28** | −.27** | −.24** | .05 | .08 | .09 | .03 |

| 19. Likelihood of HIV | 2.43 | 1.58 | −.23** | −.28** | −.19* | .03 | .12 | .12 | .07 |

| 20. Likelihood of Pregnancy | 2.35 | 1.71 | −.10 | −.14 | −.10 | .01 | .14 | .15 | .06 |

|

| |||||||||

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| 8. IPV - Indirect | --- | ||||||||

| 9. IPV - Direct | .74** | --- | |||||||

| 10. IPV - Severe | .62** | .70** | --- | ||||||

| 11. Sexual Assertiveness | −.28** | −.34** | −.19* | --- | |||||

| 12. Direct Request | −.18* | −.15 | −.16* | .45** | --- | ||||

| 13. Withholding Sex | −.12 | −.08 | −.14 | .47** | .83** | --- | |||

| 14. Risk Information | −.01 | .04 | −.04 | .19* | .57** | .58** | --- | ||

| 15. Likelihood of Unprotected Sex | .21** | .24** | .24** | −.43** | −.62** | −.67** | −.36** | ||

| 16. Encouraging Behaviors | .12 | .14 | .19* | −.37** | −.61** | −.62** | −.31** | ||

| 17. Discouraging Behaviors | −.04 | .00 | −.05 | .19* | .52** | .51** | .41** | ||

| 18. Likelihood of STD | .13 | .22** | .16* | .07 | .08 | .19* | .15 | ||

| 19. Likelihood of HIV | .14 | .22** | .19* | .04 | .16* | .24** | .26** | ||

| 20. Likelihood of Pregnancy | .10 | .14 | .14 | .10 | .12 | .17* | .18* | ||

|

| |||||||||

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| 15. Likelihood of Unprotected Sex | --- | ||||||||

| 16. Encouraging Behaviors | .75** | --- | |||||||

| 17. Discouraging Behaviors | −.50** | −.57** | --- | ||||||

| 18. Likelihood of STD | −.03 | −.05 | .15 | --- | |||||

| 19. Likelihood of HIV | −.06 | −.07 | .14 | .74** | --- | ||||

| 20. Likelihood of Pregnancy | −.07 | −.03 | .10 | .55** | .67** | --- | |||

Note. p<.05,

p<.01.

Seven items measured intimate partner violence (IPV; Whitmire, Harlow, Quina, & Morokoff, 1999). Participants were asked, “How often in your life has a sex partner done these things to you?” Items ranged from threatened to hit you or throw something at you to threatened or attacked you with a knife or gun. Responses were rated on 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Items were averaged to create three indicators of IPV (indirect, direct, and severe). Means and intercorrelations are shown in Table 1.

Participants also completed the 18-item Sexual Assertiveness Scale (Morokoff et al., 1997), which includes subscales for sexual initiation (e.g., I begin sex with my partner if I want to), sexual refusal (e.g., I refuse to have sex if I don’t want to, even if my partner insists), and pregnancy/STD prevention (e.g., I insist on using a condom or latex barrier if I want to, even if my partner doesn’t like them). Responses were rated on 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). In the present study, the latter two subscales were of primary interest. Because scores on these subscales were strongly correlated (r = .41, p < .001), items from these subscales were averaged to form a single score to be used in subsequent analyses (M = 4.04, SD = 0.68, α = .80).

Blood alcohol level and perceived intoxication

The key BAL measurement for the present study occurred just prior to starting the stimulus story. Perceived intoxication was assessed with the question “How intoxicated do you feel right now?” administered immediately after the end of the stimulus story. Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not intoxicated at all) to 6 (extremely intoxicated).

Stimulus story

The stimulus story (~ 2200 words) depicted an interaction with an attractive man (“Nick”) with whom the woman had never had sex. The participant was instructed to “imagine that you are the person being described and try to put yourself in the situation. Answer the questions as if you are the woman in the story.” To enhance the realism of the experience, the story was written in the second person (using the pronoun, “you”), the participant was instructed to project herself into the story at her current level of intoxication, and the beverages consumed by the woman and her counterpart in the story matched the participant’s expected alcohol consumption. In other words, the couple was depicted as drinking soft drinks in the control condition, weak alcoholic drinks in the placebo and low dose conditions, and strong alcoholic drinks in the high dose condition.

In the story, the couple watched movies with a group of friends. Eventually, they were alone together and began to kiss. The encounter escalated until both Nick and the woman were in kissing and petting in bed together, undressed, and highly sexually aroused; this part of the story was eroticized to evoke sexual arousal in the participant and further enhance realism. As the opportunity for sexual intercourse unfolded in the story, it became apparent that neither Nick nor the woman had a condom. However, the woman was portrayed as being “on the pill” (i.e., using oral contraceptives) to minimize the potentially confounding influence of concern about pregnancy. The story ended with Nick’s suggestion that they engage in vaginal penetration despite not having a condom. After the story, participants rated (in this order) their perceived intoxication, likelihood of insisting on condom use, likelihood of engaging in genital intercourse despite the lack of a condom, and likelihood of health consequences.

Condom insistence

Three subscales were adapted from the Condom Influence Strategy Scale (Noar, Morokoff, & Harlow, 2002) to assess participants’ strategies for insisting on condom use: Direct Request, Withholding Sex, and Risk Information. Items began with the stem, “How likely are you to…,” and were rated on 7-point Likert scales ranging from 0 (definitely unlikely) to 6 (definitely likely). Direct Request (alpha = .84) was measured with three items: ask that we use condoms during sex, tell Nick that I would be more comfortable using a condom, and be clear that I’d like us to use condoms. Withholding Sex (alpha = .94) consisted of three items: tell Nick that I will not have sex with him if we do not use condoms, let Nick know that no condoms means no sex, and tell Nick that I have made the decision to use condoms and so we are going to use them. Risk Information (alpha = .92) consisted of three items: tell Nick that we both would be safer from disease if we used a condom, explain to Nick that there are too many sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) going around to not use a condom, and tell Nick that we need to use condoms to protect ourselves from AIDS. Means were computed for each subscale and used as indicators of likelihood of condom insistence.

Likelihood of unprotected sex

This construct was measured with indicators representing likelihood of genital contact without a condom, sex-encouraging behaviors, and sex-discouraging behaviors. Indicator scores were computed as means of constituent items. Each item began with the stem, “At this point in your encounter with Nick how likely are you to…” and were rated on scales ranging from 0 (definitely unlikely) to 6 (definitely likely). Three questions assessed the genital contact without a condom: have sex with Nick, rub your clitoris against Nick’s penis without a condom, and allow Nick to put his penis inside your vagina without a condom (alpha = .85). Six items assessed sex-encouraging behaviors, e.g., let Nick know verbally that I want to keep going, let Nick know nonverbally that I want to keep going (alpha = .87). Eight items assessed sex-discouraging behaviors, e.g, try to cool things down, tell Nick that I like him but I’m not ready for this (alpha = .84).

Perceived health consequences

Three questions assessed the likelihood of experiencing health consequences if the couple had had sex: [If you had sex with Nick, how likely would you be to] contract a sexually transmitted disease in this situation, contract HIV in this situation, and get pregnant in this situation. Items were rated on Likert scales ranging from 0 (definitely unlikely) to 6 (definitely likely). Each item was used as a separate indicator of perceived health consequences. To avoid priming participants and biasing ratings of their behavioral intentions, the perceived likelihood of health consequences was measured after intentions to engage in condom insistence and unprotected sex.

Data Analytic Approach

To examine the relationships among the variables and to consider the potential moderated mediating role of sexual assertiveness, path analysis was performed using structural equation modeling (SEM) with Mplus statistical modeling software for Windows (version 4.1; Muthén & Muthén, 2007). One major advantage of this approach over traditional ordinary least squares (OLS) regression-based path analysis is the ability to enhance construct validity and control for measurement error by using multiple indicators to create latent variables for the constructs of interest. As in OLS regression each variable in the model may be regressed on all others preceding it in the hypothesized model; however, another major advantage conducting path analysis with SEM is the ability to examine all hypothesized relationships among the variables simulataneously rather than sequentially.

Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used to adjust for non-normality in the distributions of some variables. To assess both physiological and expectancy facets of alcohol’s potential effects, a latent variable for alcohol intoxication was formed using three indicators: the level of alcohol expected where low- and high-dose controls = 0, placebo and low dose = 1, and high dose condition = 2, achieved BAL measured immediately before the presentation of the stimulus story, and perceived intoxication measured immediately after the end of the story. Latent variables were also created for ASA, IPV, and the likelihoods of insisting on condom use, engaging in unprotected genital intercourse, and health consequences.

Results

Model Specification and Respecification

Descriptives and correlations among the variables are shown in Table 1. Mean (SD) achieved BALs at the start of the stimulus story were .034% (.008) and .065% (.009) in the low and high dose conditions, respectively. Mean (SD) perceived intoxication at the end of the story was 0.0 (0.0) in the control condition, 2.2 (1.5) in the placebo condition, 3.4 (1.3) in the low dose condition, and 4.0 (1.2) in the high dose condition.

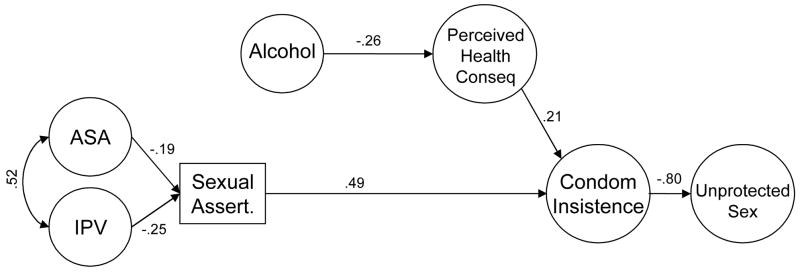

Factor loadings for the latent variables are shown in Table 2. The hypothetical model shown in Figure 1 was tested and revealed no interaction between alcohol and sexual assertiveness (p = .422). Therefore, the model was rerun without the interaction term. This simplified model demonstrated good fit, χ2(161) = 234.18, p = .0001, CFI = .956, RMSEA = .053, SRMR = .066, AIC = 9127.334. Inspection of the path coefficients revealed that the hypothesized negative relationship between alcohol and condom insistence was not significant, nor was the covariance between alcohol and ASA.5 Thus, these covariances were fixed to zero, and the model was rerun. Shown in Figure 2, the final model also provided a good fit to the data, χ2(163) = 235.56, p = .0002, CFI = .957, RMSEA = .053, SRMR = .068, AIC = 9124.135. Chi-square difference testing (Satorra & Bentler, 2001) showed that the final model fit the data no worse than the previous model, Δχ2(2) = 1.771, p = .412, and the decrease in AIC suggested that the final model was in fact a better fit than the first (Burnham & Anderson, 2004).

Table 2.

Factor Loadings for Latent Variables in the Model

| Raw Estimate | Std. Error | Z-Score | Std. Estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | ||||

| Perceived Intoxication | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .83 |

| Expected Alcohol Dose | 0.44 | 0.03 | 12.95 | .95 |

| Achieved BAL | 0.14 | 0.01 | 14.51 | .87 |

| Adult Sexual Assault | ||||

| Coercion | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .61 |

| Assault | 0.79 | 0.08 | 9.35 | .87 |

| Attempted Rape | 0.59 | 0.09 | 6.67 | .85 |

| Rape | 0.98 | 0.18 | 5.42 | .80 |

| Intimate Partner Violence | ||||

| Parcel 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .79 |

| Parcel 2 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 12.62 | .93 |

| Parcel 3 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 6.16 | .78 |

| Unprotected Sex | ||||

| Likelihood of genital contact | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .86 |

| Sex-encouraging behaviors | 0.77 | 0.06 | 13.64 | .86 |

| Sex-discouraging behaviors | −0.57 | 0.07 | −8.83 | −.62 |

| Condom Insistence | ||||

| Direct Request | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .89 |

| Withholding Sex | 1.25 | 0.08 | 15.71 | .94 |

| Risk Information | 0.98 | 0.09 | 10.71 | .60 |

| Likelihood of Health Consequences | ||||

| STD | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .78 |

| HIV | 1.41 | 0.16 | 9.00 | .95 |

| Pregnancy | 1.11 | 0.15 | 7.48 | .70 |

Figure 2.

Final model with standardized estimates. All paths in the figure are significantly different from zero (p < .05).

Testing Indirect Effects

Following procedures recommended by Bryan and colleagues for evaluating multiple mediator models in an SEM framework (Bryan, Schmiege, & Broaddus, 2007), we tested the significance of specific indirect effects and total indirect effects of adult victimization, sexual assertiveness, alcohol intoxication, and perceived health consequences on unprotected sex and of adult victimization and intoxication on condom insistence. Results are shown in Table 3. Alcohol intoxication had modest but significant indirect effects on condom insistence (β = −.06) and unprotected sex (β = .04) through its direct effect on perceived health consequences. IPV also had indirect effects on condom insistence and unprotected sex (βs = −.12 and .10, respectively) through its direct effect on sexual assertiveness. Contrary to expectations, the indirect effects of ASA on condom insistence and unprotected sex did not reach statistical significance. Through their direct effects on condom insistence, sexual assertiveness (β = −.39) and perceived health consequences (β = −.17) had significant indirect effects on unprotected sex.

Table 3.

Testing Significance of Specific Indirect Effects

| B | SE | β | Z-score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effects on Condom Insistence | ||||

| Effect of alcohol via perceived health consequences | −0.04 | 0.02 | −.06 | −2.17* |

| Effect of ASA via sexual assertiveness | −0.05 | 0.02 | −.09 | −1.86+ |

| Effect of IPV via sexual assertiveness | −0.24 | 0.10 | −.12 | −2.43* |

| Indirect Effects on Unprotected Sex | ||||

| Effect of perceived health consequences via condom insistence | −0.24 | 0.10 | −.17 | −2.43* |

| Effect of alcohol via perceived health consequences and condom insistence | 0.04 | 0.02 | .04 | 2.21* |

| Effect of sexual assertiveness via condom insistence | −0.87 | 0.16 | −.39 | −5.41*** |

| Effect of ASA via sexual assertiveness and condom insistence | 0.04 | 0.02 | .07 | 1.83+ |

| Effect of IPV via sexual assertiveness and condom insistence | 0.22 | 0.09 | .10 | 2.44* |

Note. p < .07,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Discussion

The present study examined relationships among history of adult victimization, sexual assertiveness, and risky sexual decision-making in the context of alcohol intoxication. We sought to extend previous work demonstrating a positive relationship between alcohol intoxication and intentions to engage in unprotected sex (e.g. MacDonald et al., 2000; Abbey et al., 2005) by elucidating possible mediating mechanisms, particularly situational condom insistence and perceived health consequences, and the moderating influence of sexual assertiveness. In the present study, alcohol did not promote unprotected sex directly,,but reduced perceived likelihood of health consequences of unprotected sex. In turn the less participants anticipated health consequences from unprotected sex, the less likely they were to insist on condom use. These findings are consistent with, and extend those of, Fromme and colleagues (1999), who found that participants who received alcohol, compared to those who did not, provided lower ratings of the risk of negative consequences from unprotected sex and of the likelihood that negative consequences would deter them from having sex with a new partner. Rather than asking participants whether such consequences would affect their decisions, we tested directly whether perceptions of consequences predicted their decisions within the hypothetical scenario. Also, our examination of an intermediary behavior, condom insistence, suggests that when women are intoxicated, they are less likely to insist on condom use, at least in part because they are more likely to underestimate or dismiss the possibility of health consequences.

Self-reported likelihood of condom insistence and unprotected sex were negatively related, which suggests that participants who intended to insist on condom use also intended to hold their ground and not go on to have unprotected sex. While the likelihood of unprotected sex is generally considered to be the bottom line, for women condom insistence is crucial to self-protection. Situational condom insistence was predicted by sexual assertiveness and perceived health consequences. This finding supports the value of sexual assertiveness training to enhance women’s intentions to insist on condom use, especially since the relationship between sexual assertiveness and condom insistence was robust to alcohol intoxication: the more sexually assertive, the more likely to insist on condom use, regardless of intoxication level.

Findings from the present study are also consistent with previous studies demonstrating lower sexual assertiveness in survivors of adult sexual victimization and relationship violence (Rickert et al., 2002; Rosenbaum & O’Leary, 1981). It is worth noting that our measure of background sexual assertiveness represented a snapshot in time. Items were written in the present tense, and responses ranged from never to always. Although it is impossible to know exactly what time frame participants had in mind when answering the questions on the day they came to the laboratory, answers presumably applied to their general, current, ongoing, or most recent behavior. On the other hand, our measures of prior victimization primarily applied to the past (since age 14) although victimization may have been ongoing for some women. For this reason, we placed adult victimization to the left of sexual assertiveness in our model. We do not know how sexually assertive participants were prior to their victimization experiences; however, research suggests that sexual assertiveness and sexual victimization are reciprocally related (Livingston, Testa, & VanZile-Tamsen, 2007; VanZile-Tamsen, Testa, & Livingston, 2005).

Neither IPV nor ASA showed a direct relationship with condom insistence or unprotected sex. Through its negative relationship with sexual assertiveness, a history of IPV had significant indirect effects on likelihood of condom insistence (negative) and likelihood of unprotected sex (positive). Contrary to our expectations, the indirect paths from ASA to these variables did not reach statistical significance. However, ASA and IPV were strongly correlated; including both in the model may have weakened the appearance of a relationship between ASA and sexual assertiveness. Perhaps the least sexually assertive survivors of ASA also experience higher levels of IPV related to delays in leaving violent relationships. Nonetheless, sexual risk-taking by survivors of adult victimization may be reduced by strengthening their sexual assertiveness. Certainly, caution is warranted in asserting oneself in the face of a violent partner (O’Leary, Curley, Rosenbaum, & Clarke, 1985), but our findings suggest that lack of assertiveness associated with prior victimization extends to partners who exhibit no indication of being violent. The male character in our stimulus story was someone with whom the woman had had no prior sexual relationship, and there was no explicit suggestion that he might become violent should she refuse unprotected sex; however, based on their past experiences, women with histories of victimization may have feared that he could (El-Bassel, Gilbert, Rajah, Foleno, & Frye, 2000).

The experimental paradigm used in this study allowed us to examine decision-making processes as they unfolded and to determine how these processes may be affected by alcohol intoxication. Although laboratory-based studies provide the capability of doing so, in the present study we did not attempt to parse the physiological and expectancy effects of alcohol. Although alcohol expectancy and alcohol physiology may have disparate effects on sexual behavior (George & Stoner, 2000), whether this matters to sexual risk-taking is not clear. Previous studies of sexual risk-taking have generally failed to show placebo effects (Testa et al., 2006). We also felt that in this situation taking a multidimensional approach to examining alcohol intoxication had maximal external validity, simultaneously taking into account expected dose, perceived intoxication, and blood alcohol concentration. Finally, any major inconsistency between physiological and expectancy effects of alcohol would have been apparent in their fit as indicators of the same latent variable, but none was manifested. Therefore, we consider our multidimensional examination of alcohol intoxication to be a strength of the present study.

Despite its strengths, the present study had some limitations. Administering alcohol in the laboratory requires that participants be of legal drinking age with no history of problem drinking. Consequently, it is unknown whether responses of underage or problem drinkers would be similar to those observed in the present study. To control for possible confounding variables, the situation portrayed was necessarily limited. Other types of situational influences on sexual risk-taking should be examined. Because the laboratory setting precludes the measurement of actual sexual behavior, we focused instead on behavioral intentions. Although research has generally shown medium to strong correlations between intentions and behaviors (Sheeran & Orbell, 1998), actual behaviors are also important outcome variables. As in survey research, it is possible that within a laboratory setting individuals might feel hesitant to admit a high likelihood of risky sexual behavior to themselves or others. Thus, participants may tend to underestimate or underreport their true likelihood of engaging in such behavior.

Nevertheless our findings add to existing knowledge concerning how background and situational factors can together and independently lead women to engaging in high risk sexual activity. Taking such relationships into account, future prevention interventions may benefit by tailoring programs to specific subgroups of women and providing richer information to help them avoid postdrinking sexual risk-taking.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant AA014512 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to the second author.

Footnotes

Because of lagging participant recruitment, hourly participant compensation was increased from $10 to $15 per hour partway through the study.

In the alcohol and placebo conditions, beverage cups were misted with 100-proof vodka prior to mixing the beverages in full view of the participant. Vodka or bogus vodka, presented in a brand-name bottle, was mixed with orange juice (1:4) and divided into three beverage cups. A squirt of vodka-flavored lime juice was added to the top of each cup. Prior to drinking, the participant was directed to rinse with a strongly flavored mouthwash and was told that this would allow a more accurate breathalyzer reading. This procedure was standardized across all conditions even though it was only necessary to prevent placebo participants from recognizing the lack of alcohol in their beverage. Nine minutes were allotted to consume the beverages.

The yoked control participant was not matched to the alcohol participant in any way except for the number and timing of breath analyses and, consequently, the delay until beginning reading the story (George et al., 2004; Giancola & Zeichner, 1997). Placebo participants were similarly yoked to low alcohol participants to control for variation in time.

A yoked placebo was not included for the high alcohol participants because of known difficulties in maintaining successful placebo deception for high doses (Sayette, Breslin, Wilson, & Rosenblum, 1994).

Despite random assignment, the covariance between alcohol and IPV was significant (r = −23, p < .01). Followup oneway analysis of variance with Tukey’s HSD posthoc tests revealed that the mean overall IPV score was significantly higher (p < .05) in the control condition (M = 1.61, SD = 0.72) than in the high dose alcohol condition (M = 1.28, SD = 0.30). Therefore, this covariance was included in the model.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbey A, Saenz C, Buck PO. The cumulative effects of acute alcohol consumption, individual differences and situational perceptions on sexual decision making. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:82–90. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. Mediational analysis in HIV/AIDS research: Estimating multivariate path analytic models in a structural equation modeling framework. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods & Research. 2004;33:261–304. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Retrieved February 23rd, 2007];HIV/AIDS and Women. 2007, February 20th; http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/print/overview_partner.htm.

- Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Klein DJ. Isolating the nexus of substance use, violence and sexual risk for HIV infection among young adults in the United States. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9:73–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Does drinking promote risky sexual behavior? A complex answer to a simple question. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Bernat JA, Calhoun KS, McNair LD, Seals KL. The role of alcohol expectancies and alcohol consumption among sexually victimized and nonvictimized college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenstein V, Horton NJ, Samet JH. Inconsistent condom use among HIV-infected patients with alcohol problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;73:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Rajah V, Foleno A, Frye V. Fear and violence: Raising the HIV stakes. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:154–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, D’Amico EJ, Katz EC. Intoxicated sexual risk taking: An expectancy or cognitive impairment explanation? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:54–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Drown D, Torres A, Schacht RL, Stoner SA, Norris J, et al. Establishing the Advantage of Ideographically Determined BAC Data Relative to Standard Waiting Periods; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism; Vancouver, British Columbia. June.2004. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Stoner SA. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2000;11:92–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Zeichner A. The biphasic effects of alcohol on human physical aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:598–607. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: Intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8:178–198. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Barnett NP, Pedlow CT, Murphy JG. Drinking in conjunction with sexual experiences among at-risk college student drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:697–705. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CM, Carey MP, Carey KB. Effects of a drinking event on behavioral skills and condom attitudes in men: Implications for HIV risk from a controlled experiment. Health Psychology. 1997;16:490–495. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, McCoy HV, Stevens SJ, Stark MJ. Violence and HIV sexual risk behaviors among female sex partners of male drug users. Women, Drug Use, and HIV Infection. 1998;27:161–175. doi: 10.1300/J013v27n01_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, Simpson T, Waldrop A, Larimer ME, Resick PA. Domestic violence and alcohol use: Trauma-related symptoms and motives for drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1272–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig LJ, Doll L, O’Leary A, Pequegnat W, editors. From child sexual abuse to adult sexual risk: Trauma, revictimization, and intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:455–457. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Breitkopf CR, Berenson A. Sexual and physical abuse history and adult sexual risk behaviors: Relationships among women and potential mediators. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:757–768. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JA, Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C. The reciprocal relationship between sexual victimization and sexual assertiveness. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:298–313. doi: 10.1177/1077801206297339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, MacDonald G, Zanna MP, Fong G. Alcohol, sexual arousal, and intentions to use condoms in young men: Applying alcohol myopia theory to risky sexual behavior. Health Psychology. 2000;19:290–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM. The effects of alcohol and expectancies on risk perception and behavioral skills relevant to safer sex among heterosexual young adult women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:476–485. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Schum JL. Effects of alcohol and expectancies on HIV-related risk perception and behavioral skills in heterosexual women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12:288–297. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan JL, Murphy ST, Miller LC. When women imbibe: Alcohol and the illusory control of HIV risk. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1999;23:643–651. [Google Scholar]

- Morokoff PJ, Quina K, Harlow LL, Whitmire L, Grimley DM, Gibson PR, et al. Sexual Assertiveness Scale (SAS) for women: Development and validation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:790–804. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DM, Gillmore MR, Hoppe MJ, Gaylord J, Leigh BC, Rainey D. Adolescent drinking and sex: findings from a daily diary study. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35:162–168. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.162.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. HIV Infection in Women. 2006 May 18; Retrieved March 31, 2007, from http://www.niaid.nih.gov/factsheets/womenhiv.htm.

- Newcomb MD, Carmona JV. Adult trauma and HIV status among latinas: Effects upon psychological adjustment and substance use. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8:417–428. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Morokoff PJ, Harlow LL. Condom negotiation in heterosexually active men and women: Development and validation of a condom influence strategy questionnaire. Psychology and Health. 2002;17:711–735. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Morokoff PJ, Redding CA. Sexual assertiveness in heterosexually active men: A test of three samples. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14:330–342. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.5.330.23872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Curley A, Rosenbaum A, Clarke C. Assertion training for abused wives: A potentially hazardous treatment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1985;11:319–322. [Google Scholar]

- Rickert VI, Sanghvi R, Wiemann CM. Is lack of sexual assertiveness among adolescent and young women a cause for concern? Perspectives on Sexual Reproductive Health. 2002;34:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum A, O’Leary KD. Marital violence: Characteristics of abusive couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49:63–71. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Breslin F, Wilson G, Rosenblum GD. An evaluation of the balanced placebo design in alcohol administration research. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19:333–342. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Orbell S. Do intentions predict condom use? Meta-analysis and examination of six moderator variables. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1998;37:231–250. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1998.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlai AM, Kelly JA, McAuliffe TL, Gudmundson JL, Murphy DA, Sikkema KJ, et al. Role play assessments of sexual assertiveness skills: Relationships with HIV/AIDS sexual risk behavior practices. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2:319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M. 2001. The Sexual Victimization Survey: Unpublished questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Fillmore MT, Norris J, Abbey A, Curtin JJ, Leonard KE, et al. Understanding alcohol expectancy effects: Revisiting the placebo condition. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:339–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, Koss MP. Assessing women’s experiences of sexual aggression using the sexual experiences survey: Evidence for validity and implications for research. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Trauma Exposure, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Problem Drinking in Sexual Assault Survivors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:610–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanZile-Tamsen C, Testa M, Livingston JA. The Impact of Sexual Assault History and Relationship Context on Appraisal of and Responses to Acquaintance Sexual Assault Risk. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:813–832. doi: 10.1177/0886260505276071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmire LE, Harlow LL, Quina K, Morokoff PJ. Childhood trauma and HIV: Women at risk. Philadelphia, PA, US: Brunner/Mazel, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni BD, Crawford I, Williams PG. Examining communication and assertiveness as predictors of condom use: Implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:492–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]