Abstract

Prospect theory suggests that because smoking cessation is a prevention behavior with a fairly certain outcome, gain-framed messages will be more persuasive than loss-framed messages when attempting to encourage smoking cessation. To test this hypothesis, the authors randomly assigned participants (N = 258) in a clinical trial to either a gain- or loss-framed condition, in which they received factually equivalent video and printed messages encouraging smoking cessation that emphasized either the benefits of quitting (gains) or the costs of continuing to smoke (losses), respectively. All participants received open label sustained-release bupropion (300 mg/day) for 7 weeks. In the intent-to-treat analysis, the difference between the experimental groups by either point prevalence or continuous abstinence was not statistically significant. Among 170 treatment completers, however, a significantly higher proportion of participants were continuously abstinent in the gain-framed condition as compared with the loss-framed condition. These data suggest that gain-framed messages may be more persuasive than loss-framed messages in promoting early success in smoking cessation for participants who are engaged in treatment.

Keywords: message framing, smoking cessation, bupropion

Prospect theory describes the nonlinear relationship between objective outcomes (in terms of gains and losses from some reference point) and one’s subjective reactions to them (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). The framing implications of prospect theory suggest that individuals respond differently to factually equivalent messages depending on whether they are framed so as to emphasize benefits (gain-framed) or costs (loss-framed). This idea is applicable to messages intended to promote health (Rothman & Salovey, 1997). For example, with respect to sunscreen use, a gain-framed message is “Don’t expose yourself to the sun, and you won’t risk becoming sick,” and a loss-framed message is “Don’t protect yourself from the sun, and you won’t help yourself stay healthy.” Regarding smoking cessation, “You will live longer if you quit smoking” is a gain-framed message, and “You will die sooner if you do not quit smoking” is a loss-framed message. Prospect theory suggests that if gains are made salient, people are averse to risk, and when losses are made prominent, individuals are risk-seeking. Even though the messages may be equivalent factually, the framing of the message can influence an individual’s willingness to incur risk either to encourage a desirable outcome or avoid an outcome that is unwanted (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981).

A review of the literature on message framing and health behavior suggested that gain- and loss-framed messages are differentially persuasive, depending on the health behavior in question (Rothman & Salovey, 1997). Specifically, when behaviors have a relatively certain outcome, individuals are more persuaded by gain-framed messages, and if behaviors result in an uncertain outcome, loss-framed messages are more persuasive. For example, gain-framed messages are more effective in motivating prevention behaviors such as using sunscreen at the beach (Detweiler, Bedell, Salovey, Pronin, & Rothman, 1999) because these behaviors produce relatively certain outcomes (i.e., preventing skin cancer). In contrast, loss-framed messages are more efficacious for promoting detection behaviors, such as screening mammography (Banks et al., 1995; Schneider, Salovey, Apanovitch, et al., 2001), because these behaviors have risky and uncertain outcomes (i.e., breast cancer may or may not be detected).

Historically, most antismoking messages have highlighted the costs of not quitting smoking. For example, the Surgeon General’s warnings on cigarette packs are typically loss-framed messages (e.g., “Smoking causes lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and may complicate pregnancy”), even though the effectiveness of these messages is unclear (Krugman, Fox, & Fischer, 1999). Evidence spanning over 40 years recently reviewed by the Surgeon General suggests the following: “1. Smoking harms nearly every organ of the body, causing many diseases and reducing the health of smokers in general. 2. Quitting smoking has immediate as well as long-term benefits, reducing risks for diseases caused by smoking and improving health in general” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004, p. 25). Thus, prospect theory suggests that because smoking cessation is a prevention behavior with little associated risk or uncertainty (i.e., quitting is linked to preventing health problems), it is likely that gain-framed messages would be more persuasive when attempting to encourage smoking cessation.

Findings from two previous studies support this hypothesis. Steward, Schneider, Pizarro, and Salovey (2003) examined intentions to quit as a function of message framing among smokers at various outdoor locations and public events. In this study, participants were given brochures containing framed smoking cessation messages, and gain-framed messages produced marginally greater intentions to quit than loss-framed messages. In a study that used a video-based intervention, stronger framing effects emerged. Schneider, Salovey, Pallonen, et al. (2001) presented visual and auditory gain- and loss-framed messages to smoking and non-smoking college students, and their findings revealed that gain-framed messages led to significant shifts in smoking-related attitudes and beliefs in the direction of avoidance and cessation. In addition, they observed a significant reduction in smoking behavior in the gain-framed group 6 weeks after the intervention.

Many previous studies of message framing have focused on a single act (e.g., using sunscreen lotion; Detweiler et al., 1999), and these experiments have generally provided a single framed message (e.g., a brochure or video). Examining smoking cessation is an extension of the framing literature in that it is a complex behavior that requires sustained effort, not just a single instance of behavior. Moreover, in the present study, we provided multiple framed interventions throughout treatment in an effort to sustain framing effects. For this reason, fidelity to treatment was of particular importance for the present study. Although earlier studies have investigated complex behaviors with a behavioral health outcome (e.g., exercise), they have resulted in mixed findings. For example, Jones, Sinclair, Rhodes, and Courneya (2004) did not find evidence supporting the framing hypothesis in motivating college students to engage in exercise, but McCall and Martin Ginis (2004) reported greater exercise adherence among cardiac patients who received gain-framed messages. It should be noted that both of these studies used a single framed message. Further research is needed to examine the utility of message framing to promote complex behaviors (e.g., exercise, smoking cessation), and the present study is one of the first to provide multiple framed interventions aimed at sustaining smoking cessation.

Numerous large-scale clinical trials have tested the effectiveness of sustained-release (SR) bupropion for smoking cessation and have shown that treatment with this medication significantly improves smoking cessation outcomes (Ahluwalia, Harris, Catley, Okuyemi, & Mayo, 2002; Hurt et al., 1997; Jorenby et al., 1999; Swan, McAfee, et al., 2003; Tønnesen et al., 2003). A recent meta-analysis of bupropion SR clinical trials found that this medication was an effective smoking cessation aid (Scharf & Shiffman, 2004), and the U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline identifies bupropion SR as a first-line medication for smoking cessation (Fiore et al., 2000).

Although most clinical trials evaluating bupropion SR have provided brief behavioral counseling (e.g., 7–9 weeks; Ahluwalia et al., 2002; Jorenby et al., 1999), only two studies have investigated aspects of counseling interventions used in bupropion clinical trials (Hall et al., 2002; Swan, McAfee, et al., 2003). Further research is needed to examine factors that may help to maximize the effectiveness of psychological interventions provided with bupropion and other pharmacotherapies. Factors that determine the persuasiveness of the messages that clinicians give their patients regarding smoking cessation warrant examination.

Toward this end, in the current investigation, we evaluated the effects of message framing in a smoking cessation clinical trial using bupropion. The study delivered smoking cessation messages based on the U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline for brief advice and in a manner such that they could reasonably be provided in a primary care office (i.e., through two short videos, print matter, and a water bottle and air freshener with printed slogans on them). On the basis of prospect theory and the conceptualization of quitting smoking as a prevention behavior, we hypothesized that gain-framed messages regarding quitting smoking and bupropion would be more effective in promoting smoking cessation than loss-framed messages in a general population of smokers. In addition, we were interested in testing whether a gain-framed intervention would be more effective in the subset of smokers who were actively engaged in our smoking cessation program and received the entire framed intervention.

Method

Study Design

This investigation was a randomized controlled study of two framed message conditions for smoking cessation in combination with open label bupropion SR (300 mg/day). Two hundred fifty-eight cigarette smokers were randomly assigned to receive either gain- or loss-framed video and printed messages encouraging smoking abstinence. Preproduced video and printed information were chosen as the intervention media because of their reliability in delivering specific framed messages. All participants were seen at a community mental health center for 6 months and received a 7-week supply of bupropion SR. Consistent with other studies (Hurt et al., 1997; Tønnesen et al., 2003) and recent recommendations (Hughes et al., 2003), we assessed multiple outcomes. The primary outcomes analyzed were biochemically verified continuous abstinence over the 6-week treatment and point prevalence abstinence in the last 7 days of treatment, and we hypothesized that the gain-framed condition would produce higher rates of abstinence from cigarette smoking. Written informed consent was provided by all participants at the first study visit. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Yale University School of Medicine.

Participants, Screening, and Randomization

To be eligible, smokers had to be between the ages of 18 and 70, speak English, smoke at least 10 cigarettes per day, have an expired carbon monoxide (CO) level greater than 10 parts per million (ppm), and had to have made at least one prior attempt to stop smoking. No more than one person per household was allowed to enroll. Women were excluded if they were pregnant, nursing, or not using a reliable form of birth control. Smokers were excluded for current serious neurologic, psychiatric, or medical illness (as assessed by the study physician); sharing immediate work environment with a current or past participant; current alcohol dependence; current major depressive episode; history of anorexia nervosa or bulimia; current use of psychoactive medications; history of seizure disorder; previous hypersensitivity to bupropion; or current use of smokeless tobacco, pipes, cigars, nicotine replacement products, or marijuana.

Participants were recruited through newspaper and radio advertisements, press releases, mailings to physicians, and the Internet. They were screened by telephone and at two subsequent intake appointments, one of which included a physical examination with laboratory testing. Of the 412 people screened, 258 were randomized to one of the two treatment conditions (i.e., gain- or loss-frame), with randomization in blocks of 6 stratified by gender. One of the investigators (Joel A. Dubin) created the allocation sequence before study enrollment began. As each new participant was enrolled in the study, he or she was assigned the next sequential number by an investigator (Benjamin A. Toll) who remained blind to message framing condition. These numbers corresponded to the participants’ gain- or loss-framed materials (i.e., water bottles, air fresheners, and smoking cessation handouts), which had been prepackaged in opaque folders and bags by two staff members who had no interactions with study participants. The allocation sequence was kept in a locked desk by an unblinded staff member so that unblinded staff could set up the gain- or loss-framed videos during treatment sessions. Unblinded staff did not interact with participants. Participants were randomized between February 17, 2003, and July 29, 2004, and the last follow-up appointment was completed on March 2, 2005.

Treatment Period

Starting with the baseline visit (Week −1), all participants received 150 mg of bupropion SR (Zyban, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) once per day for 3 days, then twice per day for the duration of the 7-week treatment period (Ahluwalia et al., 2002; Hurt et al., 1997). During the baseline visit, a nurse practitioner gave all participants scripted message-neutral brief advice and instructions (verbal and printed) about the risks and benefits related to bupropion SR, discussed the procedures for taking the medication, and scheduled the participant’s quit date. This interaction lasted approximately 5 min and covered drug information (e.g., do not divide, crush, or chew the tablets) and study-related information (e.g., reviewing the study treatment timeline, the quit date, and postquit 3-day follow-up call). Participants also completed a small battery of questionnaires at this visit. At the end of the session, all participants viewed one of two 8-min videos (i.e., Video 1) that provided advice about quitting smoking and taking bupropion that was either gain- or loss-framed. The brief advice followed guidelines recommended by the U.S. Public Health Service for tobacco dependence treatment (Fiore et al., 2000). Typical gain- and loss-framed messages that were provided in Video 1 are displayed in Table 1. During each video, there were brief pauses at which participants were instructed to complete a small, framed packet of questionnaires encouraging smoking cessation.

Table 1.

Messages Provided in Each of the Framed Interventions

| Intervention | Gain-framed message | Loss-framed message |

|---|---|---|

| Video 1 | If you hold on to your reasons for quitting, you will have a better chance of success. | If you do not hold on to your reasons for quitting, you will have a greater chance of failure. |

| With an active support system for yourself, you are more likely to succeed. | Without an active support system for yourself, you are less likely to succeed. | |

| Video 2 | If no one smoked, 430,000 lives would be saved in the United States each year. | Because people smoke, 430,000 lives are lost in the United States each year. |

| In addition to the physical benefits of quitting smoking, it can also have a positive impact on one’s social life. | In addition to the negative physical effects of smoking, it can have a negative impact on one’s social life. | |

| In recent studies, smokers who took Zyban were more successful in quitting smoking than those who did not take Zyban. In addition, those who took Zyban were less likely to experience cravings and weight gain. | In recent studies, smokers who didn’t take Zyban were not as successful in quitting smoking as those who did take Zyban. In addition, those who didn’t take Zyban were more likely to experience cravings and weight gain. | |

| Water bottle | When you quit smoking: You take control of your health. You save your money. You look healthy. You feel healthy. | If you continue smoking: You are not taking control of your health. You waste your money. You look unhealthy. You feel unhealthy. |

| Handouts | Decide for sure that you want to quit. Think positively about how you will overcome obstacles and succeed. | Decide for sure that you want to quit. Try to avoid negative thoughts about how difficult it might be. |

| List all of the benefits of quitting smoking. Every night before going to bed, repeat one of those benefits 3 times. | List all of the costs of continuing to smoke. Every night before going to bed, repeat one of those costs 3 times. | |

| Air freshener | Start living. Stop smoking. | Stop harming yourself. Stop smoking. |

Note. Zyban = bupropion sustained release. Gain-framed messages can focus on attaining a desirable outcome or not attaining (avoiding) an undesirable outcome, both beneficial. Loss-framed messages can emphasize attaining an undesirable outcome or not attaining (avoiding) a desirable outcome, both costs.

The target quit date for each participant was set for 1 week after they started medication, usually on Day 8. Participants returned for a research session the day before their quit date (Week 0). At this visit, they viewed one of two 14-min videos (i.e., Video 2) encouraging smoking cessation with bupropion SR. The two videos included factually equivalent arguments that were either gain-framed (e.g., “As you quit smoking, you begin to add years to your life”) or loss-framed (e.g., “If you continue to smoke, you subtract years from your life”). Examples of typical framed messages provided in Video 2 are presented in Table 1. At this session, participants also received a water bottle and printed smoking cessation materials that were either gain- or loss-framed. A nurse practitioner called all participants approximately 3 days after the targeted quit date to assess smoking status, side effects, use of bupropion, and confidence about quitting smoking.

After the Week 0 session, participants returned every 2 weeks (Weeks 2, 4, and 6) to complete short batteries of questionnaires and to receive medication refills. At Weeks 2 and 4, they received printed gain- or loss-framed smoking cessation handouts, and at Week 2 they also received a gain- or loss-framed air freshener for their car. Examples of gain- and loss-framed messages on the water bottles, handouts, and air fresheners are presented in Table 1. The framed messages used throughout this study encouraged participants to attempt to quit smoking, and they highlighted the short- and long-term benefits of smoking cessation.

In an effort to ensure that participants in different conditions would not share materials, only one participant per household was allowed to enroll in the study, and participants were excluded if they shared an immediate work environment with a current or past participant. All research assistants who conducted study interviews were blind to study condition. The nurse practitioners were blind until the end of the baseline session, at which time they set up the appropriate framed video (i.e., Video 1), according to the condition to which the participant was randomized. The nurse practitioners also set up Video 2, but they had no interactions with participants during the research session in which Video 2 was viewed. The nurse practitioners broke the blind to set up these videos because the majority of the relatively small staff needed to be blinded. Although the nurse practitioners called participants 3 days after their quit date, this was a brief scripted telephone call that was message-neutral.

There were several instances in which the nurse practitioners were unavailable to set up the framed videos. At these times, unblinded staff set up Video 1 and Video 2, but these unblinded staff never had any interactions with participants. All research assistants and nurse practitioners were trained to minimize conversation with participants outside of the protocol to prevent them from making any gain- or loss-framed statements to participants. To increase adherence to this rule, we audiotaped all sessions with participants, and weekly written feedback regarding taped interactions was provided by one of the investigators (JLC). Although written feedback was provided for relatively few taped interactions (i.e., 165 tapes), these procedures were implemented in an effort to provide a bogus pipeline, in which monitoring has been shown to increase the validity of self-reports among participants (Roese & Jamieson, 1993). In fact, this strategy appears to have worked fairly well, as less than 5% of the taped interactions (6/165 tapes) were rated as having any instances of framed interactions between the research assistant or nurse practitioner and the participant.

The phone calls made 3 days after participants’ quit date by the nurse practitioners could not be recorded. However, part of the general training given to staff members regarding not making framed statements to participants included training for the nurse practitioners to provide scripted message-neutral calls. Given the low proportion of framed interactions in the study sessions, it appears that the general training was effective overall, and it is unlikely that these calls contained a higher percentage of framed interactions than research sessions.

Posttreatment Period

Follow-up assessments were scheduled for 3 and 6 months after the target quit date. Participants received framed follow-up letters at Weeks 10 and 19, which encouraged them to remain abstinent by reinforcing the benefits of quitting smoking or the costs of not quitting for the gain- and loss-framed conditions, respectively.

Assessments

At intake, participants completed a battery of questionnaires that assessed demographics, smoking history, and potential predictor variables. Severity of dependence was evaluated with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991). The alcohol and mood disorder modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders (SCID–I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) were administered to exclude individuals with current alcohol dependence or a current major depressive episode. Participants with a history of anorexia nervosa or bulimia were excluded on the basis of screening modules from the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0.0 (Sheehan et al., 1998). Symptoms of depression over the past week were assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES–D; Radloff, 1977), and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a brief screening measure for alcohol problems, was used to characterize the sample with regard to alcohol problems (Connors & Volk, 2003). Serum cotinine was measured to document history of nicotine exposure. At each weekly/biweekly appointment, weight, CO, and reports of smoking and drinking were assessed, with the latter measured using timeline follow-back methods beginning 30 days prior to screening (Brown et al., 1998; Sobell & Sobell, 1992, 2003). Weight was assessed with shoes off.

After the framed video was presented at Week 0, all participants completed a postintervention questionnaire, which evaluated several aspects of the video. First, knowledge about the information presented in the video was assessed by creating a sum of the number of correct responses to four items: (a) the cause of the largest number of deaths in the United States, (b) the amount of money that a pack-a-day smoker will save in a year of not smoking, (c) how many hours per day smoking will shorten a smoker’s life over a 70-year life span, and (d) how bupropion SR helps people in the process of quitting. Second, using a 5-point scale, three items evaluated how believable, interesting, and confusing the video was. Third, participants rated how heavily the video focused on the benefits or the costs of smoking cessation on a scale of 1 (It focused heavily on the benefits of quitting smoking) to 5 (It focused heavily on the costs of continuing to smoke). Last, the overall tone of the video was rated on a scale from 1 (extremely negative) to 5 (extremely positive).

Bupropion SR adherence was monitored with electronic drug exposure monitor caps (APREX, Union City, CA), which recorded the time and day that the pill bottle was opened. Percent adherence equaled the number of times the bottle was opened divided by 95 (the number of times bupropion should have been taken over the 7-week treatment period; Kastrissios & Blaschke, 1997).

Adverse events were obtained weekly/biweekly using a checklist of commonly reported events for bupropion SR, rated on a scale from 0 (not present) to 3 (severe). Other concerns were elicited with open-ended questions.

Outcome Measures

Two primary smoking cessation outcomes were examined: (a) continuous 6-week abstinence from the quit date, and (b) point prevalence abstinence over the last 7 days of the 6-week treatment time period. Abstinence from smoking was defined as self-reported abstinence (no smoking, not even a puff) during the specified postquit treatment period, verified by an exhaled CO level ≤ 10 ppm (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002). Participants who dropped out or missed multiple appointments were considered to be smoking. Data for a single missed appointment were coded abstinent when the participant reported not smoking, and a CO ≤ 10 ppm was obtained at the appointments before and after the missed session. Secondary outcomes included 7-day point prevalence abstinence at the 3- and 6-month follow-up appointments and survival analyses for time to first cigarette during the study treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were analyzed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. With a planned sample of 125 participants in each group, this study was powered to detect an effect size of w = .20, with power = 0.89, and α = .05. No adjustments to sample size due to multiple comparisons of multiple endpoints were made. To examine treatment effects, we analyzed between-groups differences in the smoking cessation outcomes (continuous and end of treatment 7-day point prevalence abstinence) using logistic regression analyses, with the gain-framed compared with the loss-framed condition as a main effect. Time-to-event (i.e., time to first cigarette) analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier method for data display and the maximum likelihood method for comparison of the groups with missing data censored.

Previous research has suggested that women may be less successful in quitting smoking than men (Bjornson et al., 1995; Royce, Corbett, Sorensen, & Ockene, 1997; Scharf & Shiffman, 2004; Swan, Jack, & Ward, 1997), so main effects for gender along with the interaction of gender and message framing were examined in all regression models. These two main effects (message framing and gender) and their interaction (Message Framing × Gender) were tested together in single regression models for all smoking outcome analyses. Analyses were conducted both using the intention-to-treat (ITT) population and the subset of treatment completers (n = 170). All participants who attended the first study treatment session, at which medication was dispensed and the message framing intervention initiated, were included in the ITT population. Analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.1 for Windows (SAS Institute, 2003).

Results

Participant Characteristics

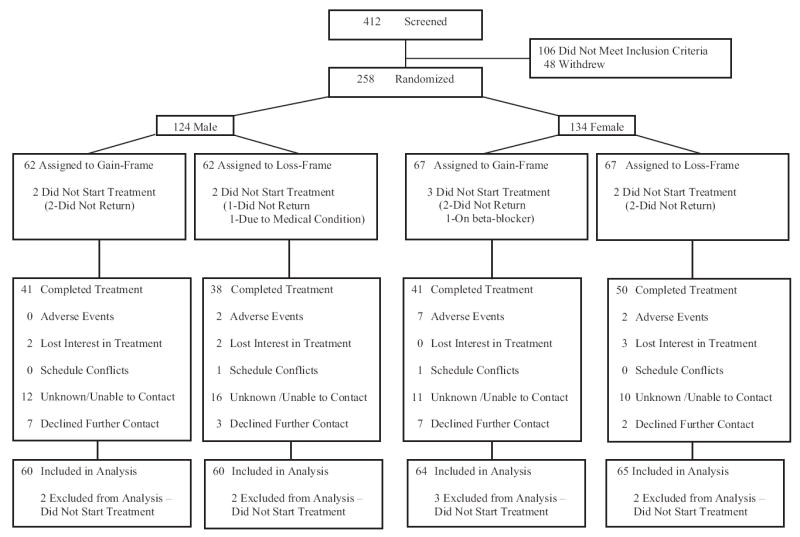

The flow of participants from initial screening to study completion is presented in Figure 1. Of the 412 participants who were screened, 258 were randomized to the gain- or loss-framed condition; 249 participants attended the first study treatment session and made up the ITT sample. As displayed in Table 2, there were no significant differences between the two intervention groups on baseline characteristics.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. Gain-framed messages focused on attaining a desirable outcome or not attaining (avoiding) an undesirable outcome. Loss-framed messages emphasized attaining an undesirable outcome or not attaining (avoiding) a desirable outcome.

Table 2.

Pretreatment Characteristics of Participants by Study Condition

| Gain (n = 124) | Loss (n = 125) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 42.4 ± 11.47 | 42.9 ± 11.56 | .75 |

| Male (%) | 48.4 | 48.0 | .95 |

| White (%) | 79.8 | 84.0 | .39 |

| Body mass index | 28.8 ± 6.05 | 27.7 ± 6.11 | .14 |

| Education (%) | .31 | ||

| High school graduate or less | 32.8 | 40.2 | |

| Some education after high school | 56.6 | 46.7 | |

| College graduate or more | 10.7 | 13.1 | |

| Marital status (%) | .74 | ||

| Married or cohabitating | 48.4 | 52.0 | |

| Divorced or separated | 21.0 | 20.8 | |

| Never married | 28.2 | 26.4 | |

| Widowed | 2.4 | 0.8 | |

| Full-time employment (%) | 67.5 | 61.9 | .37 |

| No. of cigarettes smoked per day | 22.2 ± 8.77 | 22.9 ± 9.51 | .52 |

| Years of smoking cigarettes | 25.1 ± 11.40 | 25.6 ± 11.61 | .73 |

| No. of previous attempts to quit | 5.2 ± 6.57 | 6.6 ± 16.21 | .41 |

| Expired carbon monoxide (ppm) | 22.0 ± 10.87 | 22.0 ± 8.31 | .94 |

| Serum cotinine (ng/ml) | 272.2 ± 126.10 | 299.0 ± 122.70 | .09 |

| FTND score | 5.3 ± 2.04 | 5.5 ± 2.03 | .51 |

| Other smokers in household (%) | 33.1 | 38.4 | .38 |

| CES–D score | 9.2 ± 6.93 | 8.2 ± 6.83 | .23 |

| AUDIT score | 3.2 ± 2.75 | 3.6 ± 3.51 | .40 |

| Current alcohol abuse | 22.58 | 29.60 | .21 |

| Past alcohol dependent | 7.83 | 10.26 | .52 |

| Drinkers (%) | 74.2 | 68.0 | .28 |

| Percentage of days abstinent (drinkers) | 69.5 ± 32.11 | 71.9 ± 27.15 | .60 |

| Percentage of days heavy drinkinga | 3.4 ± 6.86 | 4.9 ± 8.98 | .21 |

Note. Except as indicated, data are means ± SDs. FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; CES–D = Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression scale; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Defined as drinking five or more standard drinks on an occasion (for men) or four or more standard drinks on an occasion (for women).

Manipulation Checks

As expected, no differences in general evaluations of the messages emerged. The gain- and loss-framed videos were rated as being equally believable (gain-frame: M = 4.10, SD = 0.71; loss-frame: M = 4.09, SD = 0.89), interesting (gain-frame: M = 3.61, SD = 0.85; loss-frame: M = 3.66, SD = 0.80), and clear (gain-frame: M = 1.07, SD = 0.34; loss-frame: M = 1.08, SD = 0.35). Participants demonstrated similar smoking cessation knowledge scores across the two conditions (gain-frame: M = 2.75, SD = 0.68; loss-frame: M = 2.70, SD = 0.64). However, consistent with the objective of the study, differences emerged on specific manipulation check items. Participants in the gain-framed condition rated the video as focusing more on the benefits of quitting smoking (M = 1.15, SD = 0.52), whereas participants in the loss-framed condition rated the video as focusing more on the costs of continuing to smoke (M = 1.82, SD = 1.49), F(1, 233) = 20.78, p < .01. In addition, the overall tone of the video was rated as more positive in the gain-framed condition (M = 4.58, SD = 0.59) than in the loss-framed condition (M = 3.68, SD = 1.23), F(1, 236) = 52.20, p < .01.

Treatment Exposure

The two experimental groups were similar in the percentage of participants who completed treatment (gain-framed: 66.1%, 82/124; loss-framed: 70.4%, 88/125) and the number of sessions attended during the treatment phase of the study (gain-framed: M = 3.13, SD = 1.37; loss-framed: M = 3.27, SD = 1.22). When considering the experimental groups and gender, there were also no differences in the percentage of participants who completed treatment (gain-framed/male = 68.3%, 41/60; loss-framed/male = 63.3%, 38/60; gain-framed/female = 64.1%, 41/64; loss-framed/female = 76.9%, 50/65) or the number of sessions attended during treatment (gain-framed/male: M = 3.22, SD = 1.29; loss-framed/male: M = 3.15, SD = 1.23; gain-framed/female: M = 3.05, SD = 1.45; loss-framed/female: M = 3.38, SD = 1.21). Participants in the loss-framed condition had a somewhat higher rate of adherence to bupropion SR treatment (M = 70.7%, SD = 32.24) as compared with gain-framed participants (M = 63.3%, SD = 34.97), F(1, 243) = 2.87, p = .09.

Smoking Outcome

ITT sample

Smoking abstinence data, including adjusted odds ratios and confidence intervals, are presented in Table 3. A logistic regression analysis testing continuous abstinence across the entire 6-week treatment period did not reveal a significant effect (p = .10), although participants in the gain-framed condition had higher rates of continuous abstinence (32.3%, 40/124) over the 6-week treatment than those in the loss-framed condition (24.8%, 31/125). Men tended to have higher abstinence rates than women, but again this effect was nonsignificant (32.5% vs. 24.8%; p = .09). No difference was found between the gain- and loss-framed conditions on point prevalence abstinence over the last 7 days of the trial (43.6%, 54/124 for gain-framed; vs. 41.6%, 52/125 for loss-framed; p = .66). Significant Message Framing × Gender interaction effects were not found.

Table 3.

Odds of Continuous Abstinence and Point Prevalence Abstinence for Gain- Versus Loss-Framed Messages

| 6-week continuous abstinence

|

7-day point prevalence abstinence

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

| Unadjusted model | ||||

| Message framing | 2.01† | 0.88, 4.56 | 1.17 | 0.58, 2.34 |

| Gender | 2.05† | 0.89, 4.69 | 1.01 | 0.49, 2.05 |

| Message Framing × Gender | 0.54 | 0.18, 1.65 | 0.86 | 0.31, 2.35 |

|

| ||||

| Model with treatment completers | ||||

| Message framing | 2.74* | 1.12, 6.68 | 1.84 | 0.78, 4.34 |

| Gender | 3.17* | 1.28, 7.86 | 1.64 | 0.69, 3.91 |

| Message Framing × Gender | 0.35† | 0.10, 1.22 | 0.44 | 0.13, 1.56 |

Note. n = 249 for the intent-to-treat sample, and n = 170 for the treatment completer subsample. Both groups received 300 mg/day of bupropion sustained-release. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

p ≤ .10.

p < .05.

Treatment completers

A main effect for message framing favoring the gain-framed condition was found for continuous abstinence among treatment completers, χ2(1, N = 170) = 4.87, p = .03 (47.6% vs. 35.2%; adjusted OR = 2.74, CI = 1.12, 6.68); and men were more likely to be abstinent than women, χ2(1, N = 170) = 6.18, p = .01 (49.4% vs. 34.1%; adjusted OR = 3.17, CI = 1.28, 7.86). Differences on end of treatment point prevalence abstinence were not statistically different (64.6% for gain-framed vs. 59.1% for loss-framed; p = .46). Although women in the gain-framed condition and men in either condition tended to do better than women in the loss-framed condition, the Message Framing × Gender interaction was not statistically significant (p = .10).

Of note, the rate of treatment completion did not differ between the two groups (gain-framed = 66.1%, 82/170; loss-framed = 70.4%, 88/170; p = .47), and the baseline characteristics of completers in each group were similar. However, there were differences in baseline characteristics between treatment completers and noncompleters. Specifically, as compared with noncompleters, the completer sample had a significantly higher proportion of White participants (87.1% vs. 70.9%; p = .002), older age (M = 44.35 years, SD = 11.05 vs. M = 39.05 years, SD = 11.66; p = .001), lower body mass index (M = 27.63, SD = 5.79 vs. M = 29.57, SD = 6.56; p = .02), and a greater number of years of daily smoking (M = 26.94 years, SD = 11.11 vs. M = 22.06 years, SD = 11.62; p = .002).

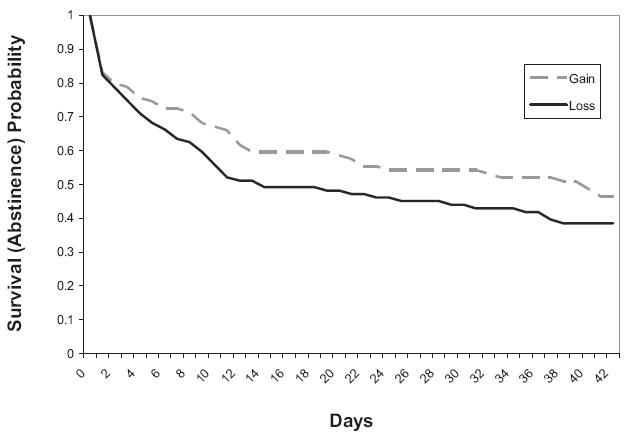

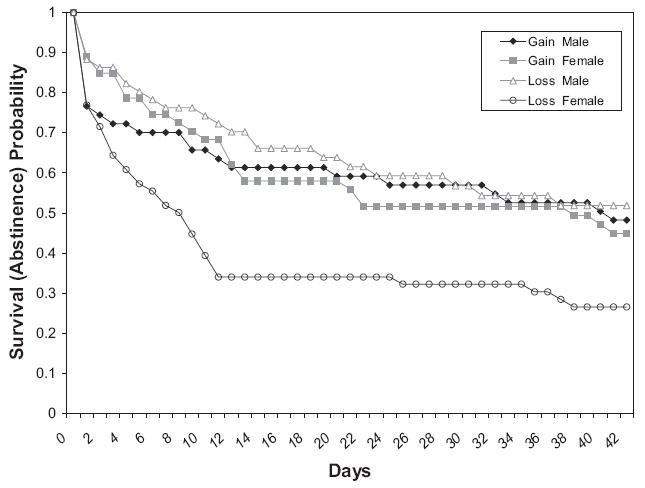

Time to First Cigarette

We examined whether the message framing intervention predicted the time until participants’ first cigarette (i.e., relapse) using the ITT sample. As presented in Figure 2, survival analyses showed a relationship between experimental condition and relapse, with participants in the gain-framed condition reporting a significantly longer time to relapse, χ2(1, N = 249) = 5.70, p = .02. This analysis also revealed a significant effect for gender, favoring men, χ2(1, N = 249) = 8.65, p < .01; and a significant interaction of Message Framing × Gender, χ2(1, N = 249) = 4.52, p = .03; the latter is displayed in Figure 3. This interaction shows that women exposed to gain-framed messages and men given either gain- or loss-framed messages showed a decreased vulnerability to relapse, as compared with women who received loss-framed messages.

Figure 2.

Survival (abstinence) analysis to end of treatment showing a main effect for message framing. Gain = messages focused on attaining a desirable outcome or not attaining (avoiding) an undesirable outcome. Loss = messages emphasized attaining an undesirable outcome or not attaining (avoiding) a desirable outcome.

Figure 3.

Survival (abstinence) analysis to end of treatment showing an interaction of Message Framing × Gender. Gain = messages focused on attaining a desirable outcome or not attaining (avoiding) an undesirable outcome. Loss = messages emphasized attaining an undesirable outcome or not attaining (avoiding) a desirable outcome.

Follow-Up Evaluations

The exploratory analyses of 3- and 6-month 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence did not reveal statistically significant differences between the two treatment groups for the ITT sample, although rates for the gain-framed condition were somewhat higher at both follow-up time points. Point prevalence abstinence rates for the gain-framed and loss-framed conditions, respectively, were 25.0% and 21.6% at 3 months (adjusted OR = 1.40, CI = 0.57, 3.48) and 16.1% and 12.8% at 6 months (adjusted OR = 2.49, CI = 0.73, 8.56). In the subsample of treatment completers, point prevalence abstinence rates were 24.4% and 17.1% at 6 months, a difference that was not statistically significant, χ2(1, N = 170) = 3.33, p = .07 (adjusted OR = 3.23, CI = 0.92, 11.42).

Adverse Events

No serious adverse events occurred during the study treatment period. There was one serious adverse event during follow-up in which a participant, who was in the loss-framed condition, was admitted to the hospital for treatment for medical problems unrelated to the study treatment (i.e., uterine fibroids). The percentages of participants reporting individual adverse events through Week 6 of bupropion SR use did not differ significantly between the groups. Consistent with other studies (Ahluwalia et al., 2002), the most common adverse events for the entire sample of participants were insomnia (63.3%) and dry mouth (57.9%).

Discussion

This is the first study to assess the effects of message framing for smoking cessation in the context of a smoking cessation clinical trial. The experimental intervention consisted of two videos and printed materials that were framed so that they emphasized either gains (benefits of quitting smoking) or losses (costs of continuing to smoke), and these materials supplemented open label bupropion SR. Analyses in the ITT sample did not reveal significant effects for either point prevalence or continuous abstinence, suggesting that a framed intervention delivered through videos and print materials may not be effective in the general smoking population from which this sample was drawn. These findings might have been due to the low intensity of the message framing intervention.

In analyses among those who completed treatment, participants in the gain-framed condition were significantly more likely to report continuous abstinence from smoking. Thus, it appears that a gain-framed intervention may be more effective in promoting continuous abstinence for participants who are actively engaged in a smoking cessation program. This might be due to the fact that these participants received the entire framing intervention (i.e., messages from both videos, all print matter, and the water bottle and air freshener). Or, perhaps the gain-framed intervention works better for a more motivated group of smokers. Not surprisingly, differences in baseline characteristics were found between those individuals who completed treatment and those who did not (Dale et al., 2001; Swan, Jack, et al., 2003). The sample completing treatment was an older group of participants who had smoked longer; perhaps these differences translated to greater responsiveness to gain-framed messages.

The fact that continuous abstinence but not point prevalence abstinence was significantly different in the completer sample suggests that the primary effect of the message framing intervention occurred in the early weeks of the treatment. Consistent with this, differences on time to the first cigarette favoring gain-framed compared with loss-framed messages were apparent very early and stabilized by about Day 12 following the quit date. Perhaps message framing is most effective clinically as a tool for initiating early cigarette abstinence. Alternatively, this finding may have been due to the fact that the largest portion of the message framing interventions (i.e., the two framed videos) was provided in the two sessions before participants’ target quit date. Subsequently, participants were given framed printed information during treatment and then framed letters during the follow-up period. In addition, the focus of the framed messages was on attempting to quit smoking and on the benefits of cessation. Future investigators should consider extending the duration and intensity of message framing interventions (e.g., additional videos at later time points during treatment), while also including framed messages that focus on maintaining abstinence after an initial quit attempt (e.g., relapse prevention skills).

Of interest, the significant interaction between gender and message frame on time to first cigarette suggests that gender may moderate the effects of message framing. Specifically, women who received gain-framed messages exhibited a decreased vulnerability to relapse, as compared with women exposed to loss-framed messages. The differences between the gain- and loss-framed message conditions were not as pronounced in men. There is emerging evidence showing that gender can moderate message effectiveness, and certain factors (e.g., issue involvement) can alter whether framed messages are persuasive for women and men (Kiene, Barta, Zelenski, & Cothran, 2005; Rothman, Salovey, Antone, Keough, & Martin, 1993). Our findings taken together with evidence showing the importance of moderators of framing effects such as need for cognition (Steward et al., 2003) and issue involvement (Rothman et al., 1993) indicate that it will be important for future investigations to test such moderators in studies of message framing for smoking cessation.

In the current study, all staff members were blind to message framing condition and provided no framed behavioral support. It is conceivable that stronger effects would have been observed if the health care provider delivered framed advice in addition to the framed print and video information. In addition, the use of dichotomous primary outcomes is another measurement constraint to consider. Previous message framing and smoking cessation research has used continuous variables as endpoints. Schneider, Salovey, Pallonen, et al. (2001) noted a decrease in number of cigarettes smoked among participants who received gain-framed messages, and Steward et al. (2003) reported greater intentions to quit among participants in the gain-framed condition. In our report, the measure of time to the first cigarette was more sensitive to message framing effects than categorical outcomes.

Taken together with prior findings (Schneider, Salovey, Pallonen, et al., 2001; Steward et al., 2003), the results of this study are consistent with the hypothesis that messages promoting smoking cessation are more persuasive if they emphasize the gains associated with quitting smoking rather than the losses associated with continued smoking, although the advantage of gain-framing was not as robustly observed here as compared with previous studies. Future studies should examine whether integrating gain-framed messages into counseling protocols can enhance these effects. Finally, research on the most effective messages for promoting interest in quitting smoking could be undertaken. In this regard, most cigarette package warning labels emphasize the risks of smoking (loss-framed) rather than the benefits of quitting smoking (gain-framed). In accordance with prospect theory and research on message framing, the use of gain-framed cigarette warning labels should be investigated (Strahan et al., 2002), and our findings, particularly in the completer sample, are consistent with this position.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants P50-DA13334 to Stephanie S. O’Malley, P50-AA15632 to Stephanie S. O’Malley, K12-DA00167 to Benjamin A. Toll; K05-AA014715 to Stephanie S. O’Malley; K02-DA16611 to Tony P. George; R01-CA68427 to Peter Salovey; and by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Veterans Affairs Special Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center Fellowship Program in Advanced Psychiatry and Psychology, Department of Veteran Affairs, to Benjamin A. Toll. We would like to thank Heather Toll and Scott Hyman for comments on drafts of this article, Elaine LaVelle for assistance with data management, and Sherry A. McKee, Denise Romano, Amy Blakeslee, Susan Neveu, Jay Kosegarten, Pamela Cox, Thomas Liss, Pamela Williams-Piehota, and Amanda McFetridge for assistance in implementing this project.

References

- Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS. Sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation in African Americans: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:468–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks SM, Salovey P, Greener S, Rothman AJ, Moyer A, Beauvais J, et al. The effects of message framing on mammography utilization. Health Psychology. 1995;14:178–184. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson W, Rand C, Connett JE, Lindgren P, Nides M, Pope F, et al. Gender differences in smoking cessation after 3 years in the Lung Health Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:223–230. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Burgess SA, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking Timeline Followback interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Volk RJ. Self-report screening for alcohol problems among adults. In: Allen JP, Wilson VB, editors. Assessing alcohol problems: A guide for clinicians and researchers. 2. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism; 2003. pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dale LC, Glover ED, Sachs DP, Schroeder DR, Offord KP, Croghan IT, et al. Bupropion for smoking cessation: Predictors of outcome. Chest. 2001;119:1357–1364. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detweiler JB, Bedell BT, Salovey P, Pronin E, Rothman AJ. Message framing and sunscreen use: Gain-framed messages motivate beach goers. Health Psychology. 1999;18:189–196. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, Goldstein MG, Gritz ER, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders, research version, patient edition. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Humfleet GL, Reus VI, Munoz RF, Hartz DT, Maude-Griffin R. Psychological intervention and antidepressant treatment in smoking cessation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:930–936. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton T, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Sachs DP, Glover ED, Offord KP, Johnston JA, Dale LC, et al. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:1195–1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LW, Sinclair RC, Rhodes RE, Courneya KS. Promoting exercise behaviour: An integration of persuasion theories and the theory of planned behavior. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9:505–521. doi: 10.1348/1359107042304605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, Rennard SI, Johnston JA, Hughes AR, et al. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:685–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrissios H, Blaschke TF. Medication compliance as a feature in drug development. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1997;37:451–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Barta WD, Zelenski JM, Cothran DL. Why are you bringing up condoms now? The effects of message content on framing effects of condom use messages. Health Psychology. 2005;24:321–326. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugman DM, Fox RJ, Fischer PM. Do cigarette warnings warn? Understanding what it will take to develop more effective warnings. Journal of Health Communication. 1999;4:95–104. doi: 10.1080/108107399126986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall LA, Martin Ginis KA. The effects of message framing on exercise adherence and health beliefs among patients in a cardiac rehabilitation program. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2004;9:122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES–D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roese NJ, Jamieson DW. Twenty years of bogus pipeline research: A critical review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ, Salovey P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:3–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ, Salovey P, Antone C, Keough K, Martin CD. The influence of message framing on intentions to perform health behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1993;29:408–433. [Google Scholar]

- Royce JM, Corbett K, Sorensen G, Ockene J. Gender, social pressure, and smoking cessations: The Community Intervention Trial For Smoking Cessation (COMMIT) at baseline. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44:359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. The SAS system for Windows, version 9.1. Cary, NC: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Scharf D, Shiffman S. Are there gender differences in smoking cessation, with and without bupropion? Pooled- and meta-analyses of clinical trials of bupropion SR. Addiction. 2004;99:1462–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TR, Salovey P, Apanovitch AM, Pizarro J, McCarthy D, Zullo J, et al. The effects of message framing and ethnic targeting on mammography use among low-income women. Health Psychology. 2001;20:256–266. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TR, Salovey P, Pallonen U, Mundorf N, Smith NF, Steward WT. Visual and auditory message framing effects on tobacco smoking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2001;31:667–682. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM–IV and ICD–10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption. Rockville, MD: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 207–224. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol consumption measures. In: Allen JP, Wilson VB, editors. Assessing alcohol problems: A guide for clinicians and researchers. 2. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism; 2003. pp. 75–99. [Google Scholar]

- SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward WT, Schneider TR, Pizarro J, Salovey P. Need for cognition moderates responses to framed smoking-cessation messages. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:2439–2464. [Google Scholar]

- Strahan EJ, White K, Fong GT, Fabrigar LR, Zanna MP, Cameron R. Enhancing the effectiveness of tobacco package warning labels: A social psychological perspective. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:183–190. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, Jack LM, Curry S, Chorost M, Javitz H, McAfee T, et al. Bupropion SR and counseling for smoking cessation in actual practice: Predictors of outcome. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:911–921. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001646903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, Jack LM, Ward MM. Subgroups of smokers with different success rates after use of transdermal nicotine. Addiction. 1997;92:207–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, McAfee T, Curry SJ, Jack LM, Javitz H, Dacey S, et al. Effectiveness of bupropion sustained release for smoking cessation in a health care setting. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:2337–2344. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tønnesen P, Tonstad S, Hjalmarson A, Lebargy F, Van Spiegel PI, Hider A, et al. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 1-year study of bupropion SR for smoking cessation. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2003;254:184–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981 January 30;211:453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: U S Government Printing Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]