INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting more than 1.5 million people in North America. Current pharmacological and surgical treatments for PD are palliative, ameliorating the classical symptoms of tremor, rigidity and akinesia, but not altering underlying disease processes (Lang and Lozano, 1998 a,b). Patient morbidity and mortality rates steadily increase as the disease progresses. Better treatments are needed and many of the approaches being developed target the primary pathophysiological sequella characterizing PD, namely: (i) the loss of dopamine (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra and (ii) degeneration of their axonal processes in the caudate nucleus and putamen. An important issue raised in testing new neuroprotective/restorative treatments is the optimal stage in the disease process to initiate therapy. Intuitively, early intervention in the degenerative process would seem preferable to slow or even reverse the damage to the neural circuitry before extensive disruptions have occurred. This was even proposed as early as 1817 by James Parkinson (Parkinson, 1817). However, current palliative drug treatments are effective in the early disease stages raising significant ethical concerns about substituting an experimental treatment for a proven therapy. Therefore, a nonhuman primate model of the earlier stages of PD would be useful for assessing the benefits and risks of early intervention.

An appropriate animal model should mimic the early stages of idiopathic PD without spontaneous recovery. Age is one of the most important components; disease onset is after age 40 in 90–95% of the patients and the incidence increases exponentially from age 65 to 90 (Lang and Lozano, 1998a). There is a ~50% loss of DA neurons in the substantia nigra in the early stages of PD, which increases to an ~80% neuronal loss in the later stages of the disease (Fearnley and Lees, 1991). The pattern of neuronal loss in the substantia nigra has been correlated with the predominant clinical features of the patient: akinesia-rigidity dominant features were associated with more severe cell loss in the ventrolateral nigra while the tremor dominant form was associated with greater neuronal loss in the medial substantia nigra and retrorubal field of A8 (Jellinger, 2002). Striatal DA fiber loss has been estimated by quantitative imaging of the type-2 vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2), which is predominately (>95%), associated with DA terminals in the striatum (Bohnen et al., 2006). The posterior putamen is most affected in early clinical PD with a ~58–77% reduction in VMAT2 binding, with smaller losses measured in the anterior putamen (42–68%) and caudate nucleus (44%) (Lee et al., 2004; Bohnen et al., 2006).

It has proven difficult to reliably produce neurotoxic lesions of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system in nonhuman primates modeling early clinical PD because of the narrow range in putamenal DA levels between symptomatic and asymptomatic animals (e.g. 92% vs 99%, Pifl and Hornykiewicz, 2006). In addition, some studies have shown partial recovery in animals with less severe lesions (Kurlan et al., 1991), particularly in younger animals receiving systemic 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6 tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) administration including via intravenous, intraperitoneal, intramuscular and subcutaneous injections (Albanese et al., 1993; Crossman et al., 1987; Moratalla et al., 1992; Rose et al., 1993; Schneider et al., 1987). This was further supported by a recent study in which spontaneous behavioral recoveries were found in 4 to 6 year old young vervet monkeys after receiving multiple intramuscular injections of MPTP (Mounayar et al., 2007). Given the importance of age in idiopathic PD, we have used middle-aged (16–19 year old) rhesus monkeys in the current study to attempt to replicate the features of early idiopathic PD. Based on factors such as life expectancy, age at puberty and brain volume, one year of rhesus life equals approximately three years of human life (Andersen et al., 1999), indicating that the 16–19 year old animals used in this study were analogous to 49 to 57 year old humans. Based on our previous studies in rhesus monkeys (Ovadia et al., 1995), we have used a low dose of 0.12 mg/kg MPTP compared to the standard dose of 0.4mg/kg, which was first reported by Bankiewicz and colleagues about two decades ago (Bankiewicz et al., 1986). We hypothesized that the low dose of MPTP injected directly via the right carotid artery, as opposed to systemic administration, would produce milder but stable parkinsonism in middle-aged rhesus monkeys; and preserve more dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and DA-containing fibers in the striatum. Because spontaneous recovery from motor symptoms is rarely seen in human idiopathic PD, such a model could be more suitable for testing neuroprotective and neurorestorative approaches than extensively lesioned animals modeling the later stages of PD. To demonstrate lesion stability, behavioral changes were closely monitored for up to 12 months following MPTP administration. A subset of eight randomly selected animals was euthanized 6–8 months after the lesion to quantify nigral DA cell loss, loss of striatal axons and striatal DA levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Twenty-seven female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) ranging in age from 16 to 19 years old and weighing between 6.2–7.9kg, were used in the study. All animals were obtained from a commercial supplier (Covance, Alice, TX) and individually housed in temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms (25 ± 1°C and 50%, respectively) on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Water was available ad libitum. Standard primate biscuits were supplemented daily with fresh fruit and vegetables. All procedures were conducted in the Laboratory Animal Facilities of the University of Kentucky, which are fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Veterinarians skilled in the health care and maintenance of nonhuman primates supervised all animal care, and all protocols were approved by the University of Kentucky's Animal Care and Use Committee.

MPTP Administration

Once adequate general anesthesia was obtained, the animal was intubated via the orotracheal method and intravenous lines were secured. As previously described (Ovadia et al., 1995), the animal was placed on a heated blanket and cardiac and respiratory parameters were monitored during the procedure. The animal was placed in the supine position with the neck hyper-extended and head slightly turned to the left. In the present study, as in our prior work, MPTP was administered to the right hemisphere of middle-aged female rhesus monkeys. Once the common carotid artery (CCA) was exposed, the external carotid artery was temporally blocked by a micro bulldog clamp to occlude blood flow. At this time, all of the CCA blood flow was diverted into the internal carotid artery. A 25 gauge butterfly needle, attached to a syringe with previously mixed MPTP solution (2mg/ml), was bent at the tip to a slight angle, and then inserted retrograde to the blood flow through the CCA wall and into the CCA lumen. The MPTP solution was delivered at a rate of 2ml/min. During this time, the animals remained stable with an increase in heart rate (up to 20–30 counts/min) but no notable changes in EKG patterns. Spontaneous respirations were maintained throughout the procedure. The average dose of MPTP administered in the present study was 0.12 mg/kg to induce early-stage parkinsonism as compared with 0.4mg/kg used in our prior studies to induce late-stage PD. At the end of the surgery, dose and volume of MPTP was double checked. In addition, ipsilateral mydirasis and muscle tension of contralateral limbs were immediately examined and recorded in the surgery notes in all animals.

Behavioral Evaluation

Home cage activity levels were conducted starting one month post MPTP administration. Behavioral measures, including distance traveled and movement speed, were quantified from videotapes using an automated video-tracking system, EthoVision (Noldus Information Technologies, Asheville, NC). The detailed procedure has been described elsewhere (Walton et al., 2006). Briefly, the tracking method relies on calibrating the software to the dimensions of the cage, so that the position of the animal can be determined in the cage based on x,y coordinates, which are then used to calculate distance moved (cm) and movement speed (cm/sec) during the observation period.

Motor dysfunctions were assessed from the same videotapes using a rating scale for MPTP-lesioned parkinsonian monkeys that was patterned after the human Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (Kurlan et al., 1991b Ovadia et al., 1995). Briefly, the videotapes were evaluated blindly and scored from 0 to 3 points by two independent experienced raters in the following categories: rigidity, bradykinesia, posture, balance, tremor, and hand dexterity. The rating scale data collected at 3, 6 and 12 months post surgery were used to show the stability of the PD features induced by using a lower dose of MPTP. Also, a levodopa drug-challenge was conducted at 5 months post MPTP administration. Each animal received an intramuscular injection of levodopa-methyl ester (50mg, Sigma Co.) and carbidopa (5.0mg, Sigma Co.) mixed separately in sterile saline, and was then videotaped for 2 hours. Responsiveness to levodopa was judged by behavioral changes in PD features using the rating scale for MPTP-lesioned parkinsonian monkeys. In addition, behavioral rotation and potential side-effects such as vomiting, dystonias, and stereotypic movements were examined as well.

Post-mortem Morphology and Neurochemistry

Eight of the twenty-seven behaviorally characterized animals were randomly selected for immunocytochemical analysis and tissue punches were obtained from six of the eight animals for neurochemical evaluations, approximately eight months after MPTP treatment. The procedure for euthanasia has been described elsewhere (Gash et al., 2005). Briefly, the animals were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital and euthanized via transcardial perfusion of ice-cold saline. Then, the brain was immediately removed and placed in an ice-cold brain mold, and sliced into 4mm-thick coronal slabs. Multiple tissue punches were taken from both sides of the caudate nucleus (n=10 for each side) and putamen (n=10 for each side). Levels of DA and DA metabolites, homovanillic acid (HVA) and 3–4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), were measured in the punches by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrochemical detection (procedures previously published in Grondin et al., 2002). The remaining sections plus the entire midbrain were immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution in 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 3 nights and cryoprotected in 30% buffered sucrose until they sank. Then, 40 µm-thick sections were cut on a sliding microtome through the striatum and the substantia nigra. One of every six sections was processed for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, monoclonal antibody, 1:1000; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) for assessment of MPTP-induced neuronal loss in the midbrain and loss of TH-positive (TH+) fiber density in the striatum (procedures described elsewhere, Gash et al., 1996; Grondin et al., 2002). It is important to note that all post mortem analyses were blindly conducted. The only information given to the research personnel performing these analyses was the animal’s ID number.

Late-Stage Parkinsonian Animals

A group of severely-lesioned animals were used for comparison, which consisted of the five monkeys previously described elsewhere (Gash et al., 2005). They were age and sex-matched to the early-stage parkinsonian animals (i.e. female rhesus monkeys, 14–17 years old). Surgical procedures for MPTP administration, behavioral testing, quantitative neuroanatomical methodology and neurochemical procedures were analogous to those described in the current study and performed by the same research personnel. To produce severe parkinsonism, these five monkeys received 0.4 mg/kg MPTP infused via the right carotid artery (i.e. a dose 3.3X that of the earlier stage animal model). For comparison, we used post MPTP behavioral measurements taken before these five severely-lesioned animals were implanted with a programmable pump and catheter to deliver citrate buffer into the dorsal supranigral region (Gash et al., 2005). The postmortem neurochemistry measures and quantitative cell counts obtained in these five severely-lesioned animals were not affected by citrate infusion and catheter implantation dorsal (above) to the substantia nigra and were comparable to published data obtained from other severely-lesioned female rhesus monkeys (Gash et al., 1996; Grondin et al., 2002).

Statistical Analyses

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. All statistical analyses were conducted using Prism 4 GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA). Stability in PD features over time was analyzed using a non-parametric Friedman’s test. Changes in locomotor activity including distance traveled and movement speed were analyzed by comparisons with pre-MPTP baseline levels with a repeated measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. Neurochemical data including changes in DA and DA metabolite levels in the striatum were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison Test. In addition, TH+ fiber density in the striatum, and TH+ neurons in the substantia nigra were based on unpaired t-tests for independent samples when comparing left and right hemispheres or comparing early- with late-stage PD animals. The same test was also used in assessing the difference in rating scales between early- and late-stage PD animals. The Welch’s correction was used if the P value was <0.05 in F-test (We did not assume equal variances). Differences of P ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. The severe PD animals were reported in a previous study (Gash et al., 2005).

RESULTS

Behavioral Evaluation

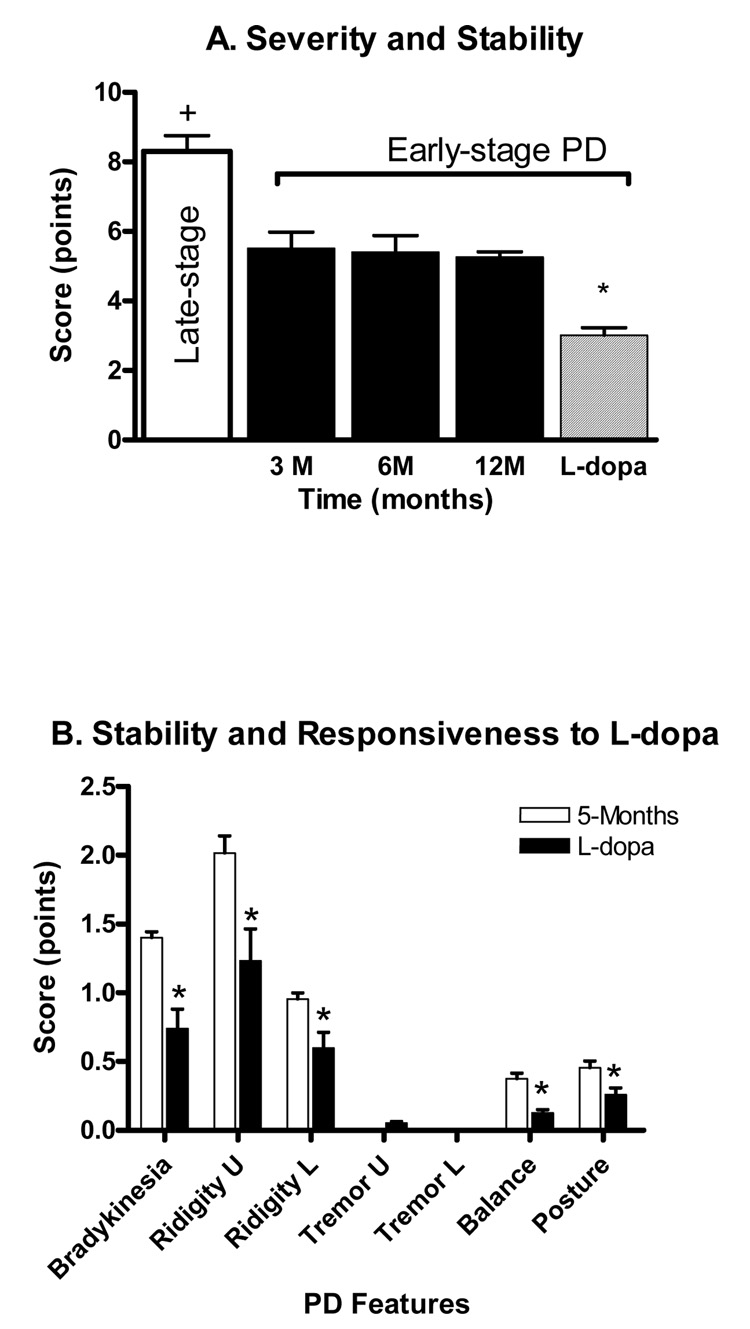

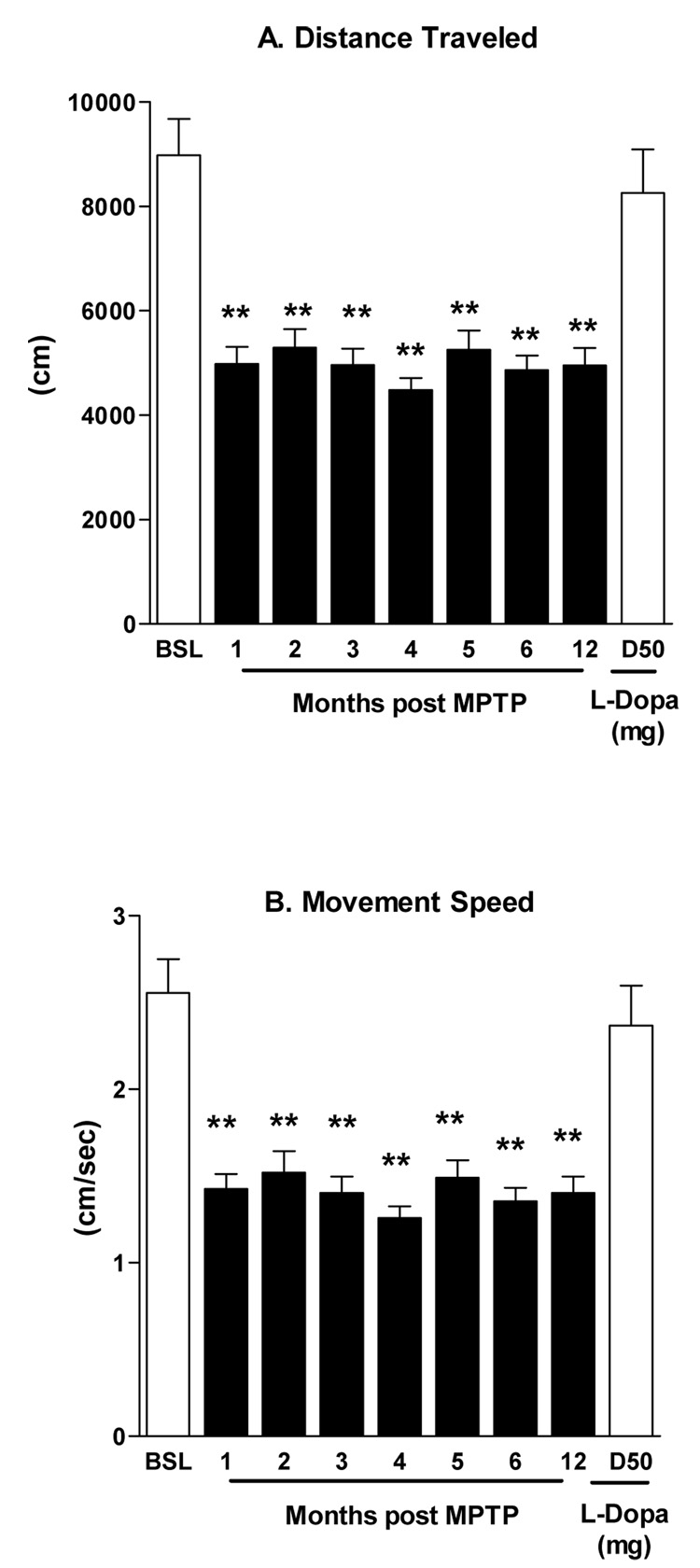

Unilateral parkinsonian features emerged by two weeks and were stable by six-eight weeks after MPTP treatment. The movement dysfunctions were continuously expressed throughout the study without evidence of either behavioral recovery or progressive functional decline (Figure 1A close bars). None of the animals required an additional dose of MPTP to maintain their level of parkinsonism. The parkinsonian features expressed included bradykinesia and rigidity of upper and lower limbs on the contralateral side of MPTP administration (Figure 1B, open bars). In addition, stooped posture and mild postural instability were evident in all animals. Severely-lesioned rhesus monkeys can express an action tremor. This feature was either absent or rarely expressed in the monkeys in this study. As shown in figure 1A, the total (cumulative) parkinsonian score of the early-stage animals was 5.3 ± 0.15 points (close bars) compared to a significantly more severe score of 8.3± 0.45 (the open bar) for the late-stage parkinsonian animals. The PD scores were consistent with the results collected using an automated video-tracking system showing the stability of the model over 12 months (Figure 2 A&B). Both distance traveled and movement speed were reduced by ~44% by one month post MPTP treatment and remained lower over the twelve month test period.

Figure 1.

A. Parkinsonian features at 3, 6 and 12 months following MPTP administration in 27 early-stage parkinsonian monkeys. No significant differences were observed from 3 through 12 months post MPTP treatment, indicating the stability of the model. A significant difference in parkinsonism severity was seen among the early-stage (5.3 ± 0.15 points) and late-stage model animals (8.3± 0.45 points) on the rating scale. +P<0.001, late- vs. early-stage. In addition, L-dopa improved overall PD rating scale in the early-stage model animals. B. Levodopa significantly improved parkinsonian features including bradykinesia, rigidity of the upper and lower limbs, balance, and postural instability. *P<0.05, L-dopa vs. other time points.

Figure 2.

Changes in locomotor function 12 months following MPTP administration in 27 early stage parkinsonian monkeys. Both the total distance traveled (A) and movement speed (B) were significantly decreased versus baseline (F=20.4, r2=0.4, P<0.001). The last bar of each panel shows that L-dopa significantly improved each measurement. **P<0.01 MPTP vs. baseline.

In addition, the parkinsonian features were levodopa responsive, with significant improvements measured following levodopa administration five months after the MPTP lesion (Figure 1B, close bars). In addition, rotational behavior was observed in 22 out of 27 animals. The average total number of turns over 60 min was 34.5±9.6. Furthermore, all animals showed a significant increase of locomotor activity assessed by distance traveled and movement speed in response to levodopa challenge (Figure 2A&B, right hatched bar).

Post-mortem Neurochemistry

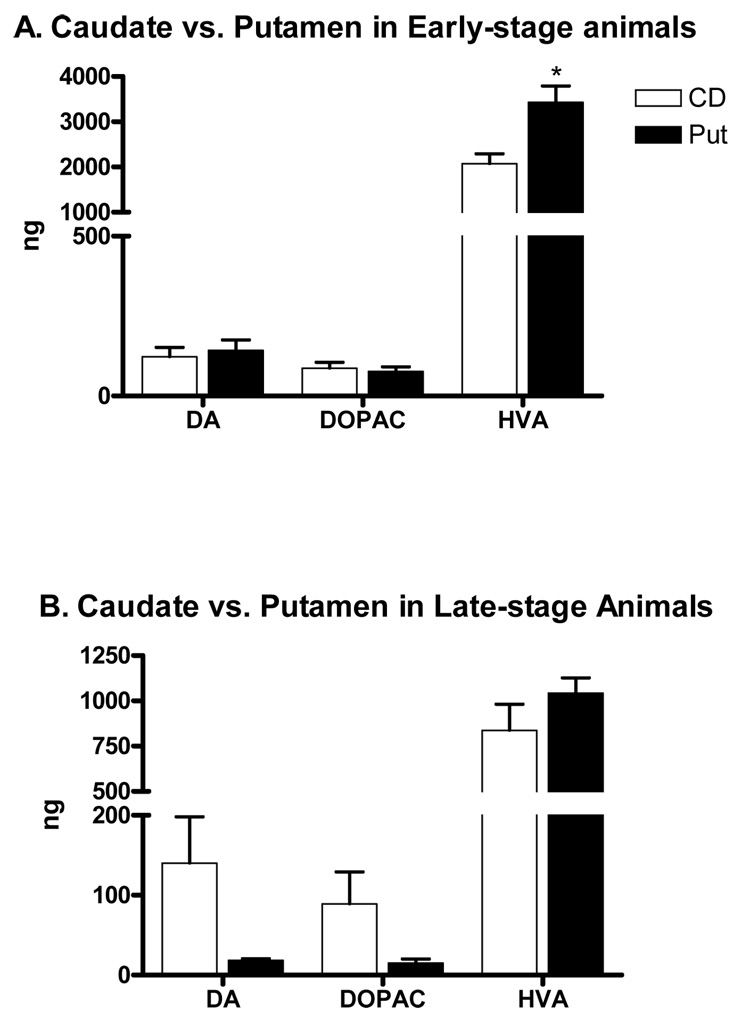

In accordance with the other effects on the nigrostriatal DA system, significant declines in DA and DA metabolite levels were found using both MPTP dose regimens. Normal values are shown in Table 1 for comparisons. In the early-stage model, tissue DA levels in the putamen were decreased by 98%, while DOPAC and HVA levels were reduced by ~95% and 83%, respectively (Table 1). In the animals modeling late-stage PD, DA, DOPAC and HVA levels were reduced by up to 99% in the putamen (Table 1). Consistent with a milder lesion, HVA levels measured in the early-stage model were significantly greater than those found in the late-stage model (P<0.05, Table 1). The HVA/DA ratios were significantly larger in the putamen of early- and late-stage animals versus the normal putamen. In addition, the DOPAC/DA ratios were significantly larger in the early-stage model versus normal putamen, but the DOPAC/DA ratios in the putamen of the late stage animals, while larger, did not reach statistical significance. In the animals with early-stage PD, no significant differences were seen between the caudate nucleus and putamen in DA and DOPAC levels (see Figure 7A). However, levels of HVA were statistically higher in the putamen than in the caudate nucleus (Figure 7A). In the animals with late-stage PD, no significant differences were seen between the putamen and caudate nucleus. Although the levels of DA and DOPAC were lower in the putamen than in the caudate nucleus, they did not reach significance due to a large variance in the caudate nucleus (Figure 7B).

Table 1.

Putamenal dopamine and its metabolites in normal and MPTP-injected side

| Control (n=5) | MPTP Early Stage (n=6) MPTP injected side | MPTP Late stage (n=5) MPTP injected side | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine1 | 9135±293 | 143±32.32** | 18.38±1.87** |

| DOPAC2 | 3997±210 | 77.39±14.47** | 15.25±4.97** |

| HVA3 | 20229±456 | 3432±361** | 1044±83.24**,+ |

| DOPAC/DA4 | 0.45±0.03 | 1.6±0.3** | 1.1±0.34 |

| HVA/DA5 | 2.35±0.12 | 69.4±6.5** | 75.7±8.4** |

Values shown are means ± S.E.M. in ng/g wet weight and means ± S.E.M. molar ratios

Dopamine, MPTP vs control: F= 981.4, r2=0.93

DOPAC, MPTP vs control: F= 333.3, r2=0.83

HVA, MPTP vs control: F= 914, r2=0.93

DOPAC/DA, MPTP vs control: F= 4.88, r2=0.06

HVA/DA, MPTP vs control: F= 41.36, r2=0.37

P<0.01 vs. control

P<0.01 early vs. late stage

Figure 7.

Whole tissue levels of DA, DOPAC and HVA in the caudate nucleus of early-stage and late-stage PD models. A) In early-stage PD animals, tissue levels of DA, DOPAC and HVA were greatly reduced in the caudate nucleus and putamen in the injected hemisphere of the animals as compared to the un-injected side of the parkinsonian animals. No significant differences in DA and DOPAC between the caudate nucleus and putamen were observed. However, a significant difference was found in HVA between the caudate nucleus and putamen. The level of HVA was about 40% higher in the putamen. B) No significant differences in DA, DOPAC, and HVA were found in late-stage animals, but they were greatly reduced as compared to the un-injected hemisphere. *P=0.009.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that a low dose of MPTP administered to middle-aged rhesus monkeys mimics some important parkinsonian features often seen in early stage idiopathic PD such as milder bradykinesia and rigidity, which can be partially normalized by levodopa treatment. Levodopa is the most efficacious drug to treat PD motor symptoms and is widely considered the "gold standard" by which to compare other therapies, including surgical therapy. Response to levodopa is one of the criteria used for the clinical diagnosis of PD. In fact, MPTP-induced PD symptoms that are responsive to levodopa therapy have been observed in human subjects who took a drug later revealed to be contaminated with MPTP (Ballard et al., 1985; Davis et al., 1979; Langston et al., 1983). Our early stage rhesus monkey model also shares this feature with the early stages of human PD in that all animals positively responded to a low-dose of levodopa/carbidopa (~6.7/0.67 mg/kg, respectively, i.m).

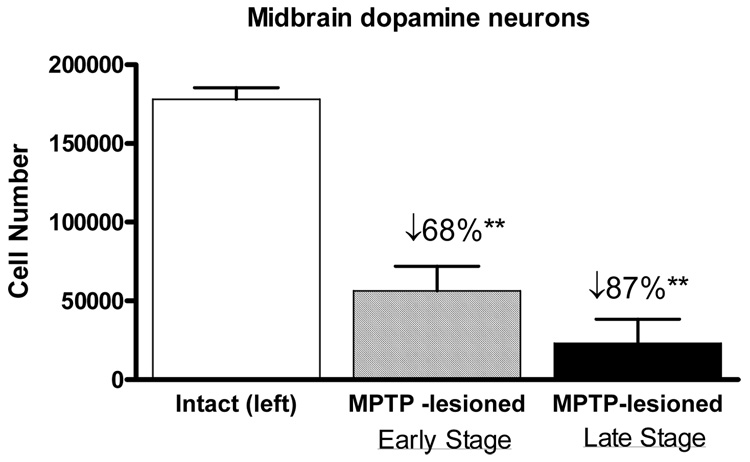

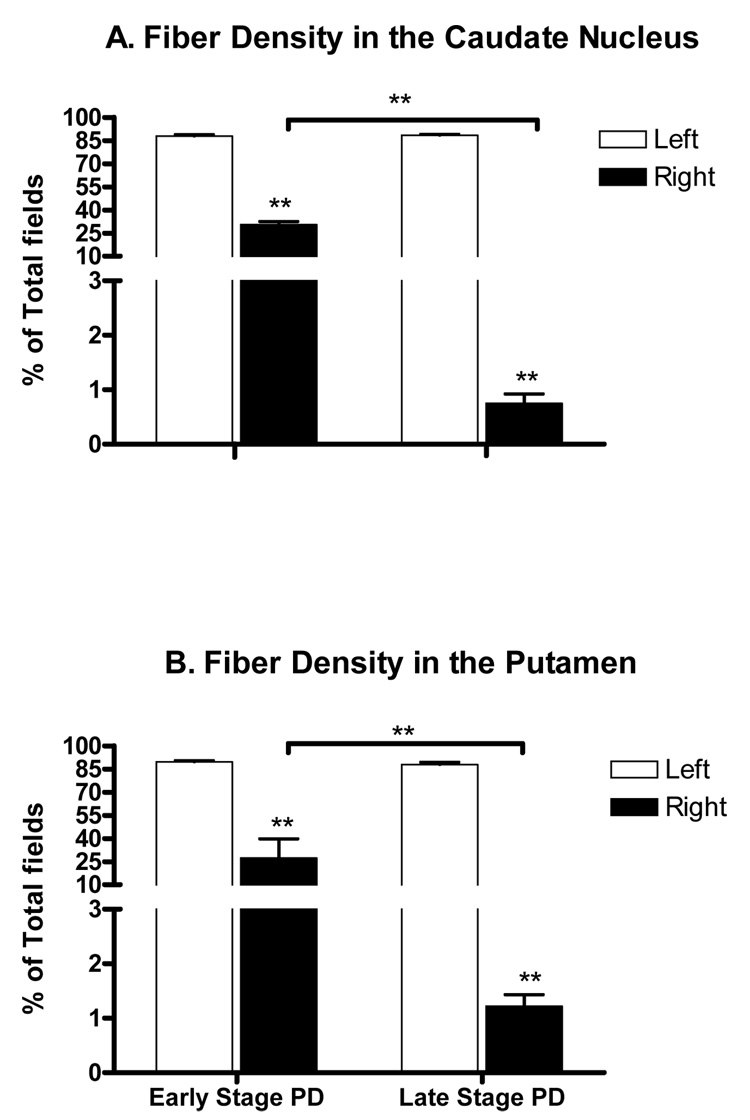

The low dose of MPTP also produces morphological and neurochemical features similar to those found in patients in the earlier stages of the disease, which include a smaller loss of DA neurons in the substantia nigra and significantly greater retention of dopaminergic fibers and DA in the striatum. By the time the features of PD have manifested and have been diagnosed, significant damage to the nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway has already occurred. In the early-stage model produced here, the most pronounced difference from the late-stage model was preservation of dopaminergic fibers in the caudate nucleus and putamen. TH+ fiber density was ~25% in the striatum of the milder lesioned animals (i.e. early-stage) compared with ~1% in the more severely esioned (i.e. late-stage) group. The decline in TH+ DA neurons in the substantia nigra was less pronounced than that seen in the striatum with a 68% to 87% loss, respectively, for the early versus the late stage model. This appears to model the progression of human PD, where an initial precipitous decline in nigral DA neurons in the first decade after the disease symptoms manifest, is followed by little further loss over the next several decades of the disease (Fearnley & Lees, 1991). This suggests that the relentless progression of disease features after the initial nigral neuron loss might be due to continuous loss of axons and terminals in the caudate nucleus and putamen.

Indeed, a highlight of the present study is that a lower dose of MPTP could not only produce stable parkinsonism behaviorally but also preserve more dopaminergic fibers in the striatum. This could provide a therapeutic target for neuroprotective agents to exert their biological effects. In human idiopathic PD, estimates of the progression of loss of dopaminergic axons and terminals in the striatum vary depending on the imaging methodology used (Lang and Lazano, 1998; Bohnen et al., 2006). Animal studies support the concept that cell bodies of DA neurons can be maintained in the substantia nigra for long periods following axonal loss in the striatum (Kirik et al., 2000). Recently, axonal degeneration has been demonstrated to be an active process that can be prevented, effectively maintaining axons for extended periods following axotomy or injury (Araki et al., 2004; Sasaki et al., 2006). Thus, the dopaminergic axons/terminals in the striatum and the neuronal cell bodies in the substantia nigra can be considered as two separate compartments and therefore separate targets for therapeutic intervention. The early-stage model with greater preservation of striatal axons could be quite useful for testing strategies to preserve and restore dopaminergic innervation in the striatum.

Studies in nonhuman primates indicate that DA metabolism increases in the striatum as DA levels decline, with the ratio of DOPAC and HVA significantly increased over control values. Pifl and Hornykiewicz (2006) recently reported that in presymptomatic MPTP-treated rhesus monkeys, putamenal DA levels were 8% of controls, but DOPAC/DA and HVA/DA ratios were 2–5 fold higher than control values. In symptomatic MPTP-treated monkeys, putamenal DA levels were < 1% of control levels. Here, we report that in early-stage PD animals, putamenal DA levels were only 1.5% of normal age-matched animals (143 vs. 9135 ng/g w. weight) while HVA/DA ratios were > 25-fold higher than those of normal animals (69 vs. 2.4 ng/g w. weight, for the data of normal age-matched control animals, seeGerhardt et al., 2002). Although there was a significant difference in striatal DA between early- and late-stage animals (P<0.01), the loss of DA was extensive in both groups (143 ng for the early- and 18.4 ng/g w. weight for the late-stage model) compared with normal animals (9135 ng/g w. weight). Thus, while the TH+ fiber density was more preserved in the striatum of the milder parkinsonian animals, DA synthesis is greatly diminished in these animals. Interestingly, putamenal DA levels have been shown to be diminished by 98% in subjects ranging from 1–5 on Hoehn and Yahr scores (Kish et al., 2008), supporting the massive loss of DA in the putamen analogous to our animal models.

Pathological studies of human PD showed the putamen to be more affected than the caudate nucleus (Kish et al., 1988; Brooks et al., 1990). However, heterogeneous changes were not seen in the present study, although a trend for higher DA and DOPAC levels and TH+ fiber density was observed in the caudate nucleus. Heterogeneous damage in the basal ganglia following MPTP administration in nonhuman primates has been a source of some debate. Studies have shown that the putamen was more affected than the caudate nucleus in squirrel, and cynomologus monkeys and baboons following chronic rather than acute administration of MPTP (Moratalla et al., 1992; Hantraye et al., 1993). However, other nonhuman primate studies report contradictory results (Elsworth et al., 1989; Pifl et al., 1988 & 1991; Alexander et al., 1992; Perez-Otano et al., 1994). For example, Elsworth et al. (1989) showed that DA and HVA levels were depleted to a greater extent in the caudate nucleus as opposed to the putamen in mildly lesioned African Green monkeys. Species and technical differences in MPTP administration may account for the varying results reported in striatal dopaminergic depletion.

Few studies have specifically addressed the stability of milder parkinsonian features induced by a low dose of MPTP administered through intracarotid artery injection in rhesus macaques, which is a widely used species in PD related research (for reviews see Soderstrom et al., 2006; Jakowec and Petzinger 2004). An intriguing question raised from our study is how such a low dose of MPTP can produce long-term milder but stable parkinsonism in rhesus monkeys without spontaneous recovery. Converging evidence from many studies has shown that there are at least two important factors determining the probability of spontaneous recovery, namely: route of administration of MPTP and age of the animals. The administration of MPTP through a number of different routes and dosing regimens has led to the different models of parkinsonism in nonhuman primates. However, the most spontaneous recovery reported in previous publications occurs in systemic models including intravenous, intraperitoneal, intramuscular and subcutaneous injections (Albanese et al., 1993; Crossman et al., 1987; Moratalla et al., 1992; Rose et al., 1993; Schneider et al., 1987). The assumption was further supported by a recent study in which spontaneous behavioral recoveries were found in 4 to 6 years old young vervet monkeys after receiving multiple intramuscular injections of MPTP (Mounayar et al., 2007). The results from our study support that a milder but stable parkinsonism can be produced by controlling for the route of neurotoxin administration and age of the animals as discussed below.

The propensity for spontaneous recovery following MPTP lesions may also be related to the age of the animal at the time of the lesion. Prior data show that the behavioral response to MPTP appears to be age-dependent, whether given systematically or via the intracarotid route (Degryse et al., 1986; Narabayashi et al., 1987; Rose et al., 1993; Ovadia et al., 1995; Irwin et al., 1997; Mounayar et al., 2007). For example, younger animals (<10 years old) may have little or no behavioral response to MPTP as previously reported (Ovadia et al, 1995). Here, we used middle-aged rhesus monkeys (16–19 years old) that are somewhat analogous to 48–57 year old humans, an age range that is well within the range seen for age of onset of idiopathic PD. In addition, increasing incidence of PD with advancing age suggests that age-associated changes in the nigrostriatal system play a crucial role in neurodegeneration in PD (Mayeux et al., 1995; McCormack et al., 2004). Recent studies have demonstrated that PD is associated with defective mitochondrial function as evidenced by defects in mitochondrial DNA (Trimmer et al., 2000; Smigrodzki et al., 2004; Bender et al., 2006). Studies show that 1-methyl–4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), which is converted from MPTP, is a mitochondrial toxin (Nicklas et al., 1985) that rapidly accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix (Ramsay et al., 1986) leading to a deficit of ATP and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by inhibiting Complex I (for a review, see Przedborski et al., 2004). Therefore, in adult neurons, which depend primarily on mitochondrial ATP production to meet bioenergetic demands, any compromises in mitochondrial function place neurons at a high risk for losses of normal function or death. Furthermore, an increasing number of studies have shown that there are several aged-related changes in the nigrostriatal system, including, i) mitochondrial DNA deletions which cause functional impairment of substantia nigra neurons (Kraysberg et al., 2006); ii) decreases of dopaminergic fiber density in the putamen (Collier et al., 2007); and iii) reductions of DA content in the striatum (McCormack et al., 2004) all of which suggest that compensatory effects would be significantly diminished in older animals. Therefore, it is not surprising that behavioral recoveries were not seen in middle-aged animals even when receiving a low dose of MPTP.

Although results indicate that a low dose of MPTP can produce a behaviorally milder and pathologically lesser denervated model in middle-aged rhesus monkeys, our model still has limitations as a model of early stage of PD. First, there is a greater loss of DA neurons in the substantia nigra and DA content in the striatum than early-stage human PD. As aforementioned, there is a loss of about 50% of DA neurons in substantia nigra in early PD (Fearnley and Lees, 1991). Second, because MPTP was injected unilaterally, potential compensatory effects from the MPTP un-injected side should be considered if this model is used for preclinical trails to evaluate neuroprotective and/or neurorestorative therapies. For example, pharmacological MRI studies have revealed potential compensatory effects in unilateral MPTP lesioned middle-aged rhesus monkeys (Zhang et al., 2006). In that study, strong deactivations were found in the contralateral side to counter apomorphine-evoked activations in the striatum on the MPTP-injected side. Furthermore, MPTP administration produces an acute neurotoxin lesion model and does not promote progressive neurons loss in the midbrain.

In summary, our data support that a low dose of MPTP can induce milder but stable parkinsonian features in middle-aged female rhesus monkeys while preserving more dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and terminals in the striatum. In addition to the PD features displayed, all animals positively responded to L-dopa treatment. Overall, our study supports that a stable, earlier stage model of PD can be produced in the rhesus monkey by controlling for several factors, including the animal’s age as well as dose and route of administration of the neurotoxin, MPTP.

Figure 3.

TH+ cell numbers in the substantia nigra on the uninjected and injected hemispheres of the early stage and late stage parkinsonian monkey models. Compared to the uninjected side, a loss in TH+ neurons of approximately 68% was seen in the substantia nigra in the early stage parkinsonian animals versus an 87% reduction in the late stage parkinsonian animals. ** P<0.01 vs. uninjected side.

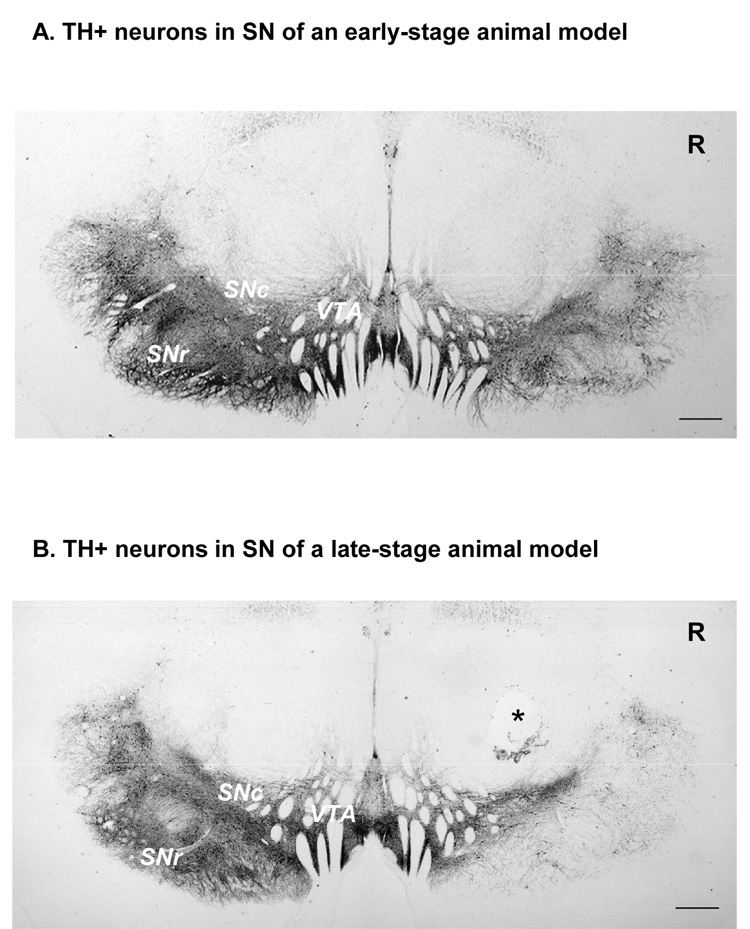

Figure 4.

Both panels show representative examples of remaining TH+ neurons in the substantia nigra in an early stage (A) versus late stage (B) monkey model. In both stages of MPTP-induced parkinsonism, the VTA on the lesioned side was less affected. In contrast, the lateral region of the substantia nigra was most affected by the MPTP lesions. Tissue loss (asterisk) during processing for immunocytochemistry produced the cavitation in b). Scale bar = 1mm. R= right side; SNc= substantia nigra compacta; SNr= substantia nigra reticulata; VTA= ventral tegmental area;

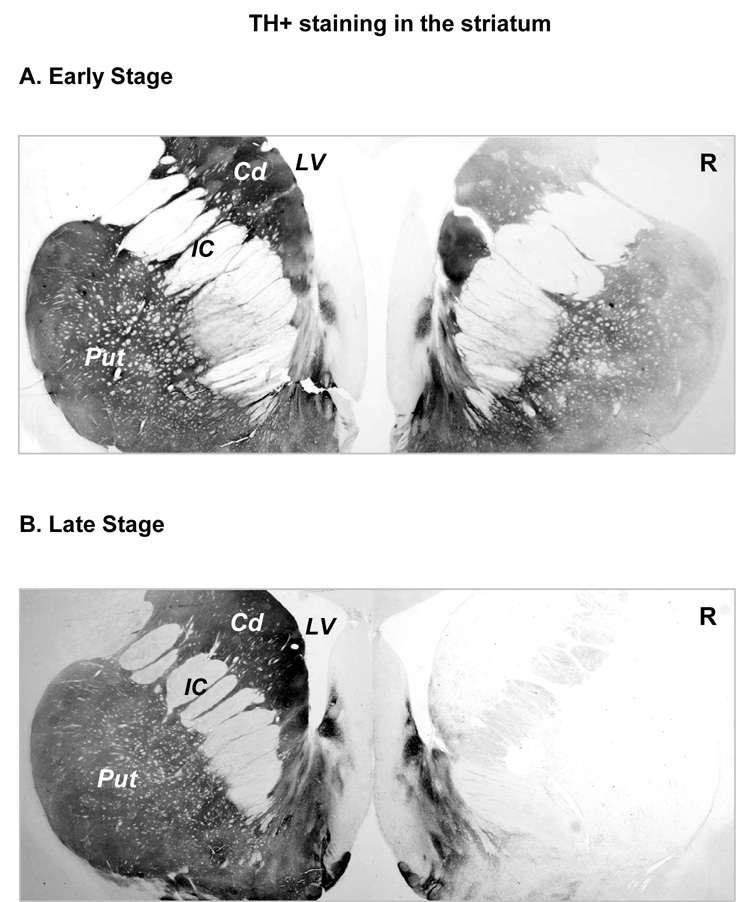

Figure 5.

TH+ staining in the striatum. A. TH+ staining in a section through the striatum from an early stage parkinsonian monkey. Compared to the uninjected side, MPTP administration produced an uneven loss of TH+ fibers in the putamen. There appeared to be a greater loss in the lateral putamen and dorsal caudate nucleus. B. TH staining in a late stage parkinsonian monkey. Compared to the uninjected side, very few TH+ fibers could be observed. Scale bar =1mm. Cd= caudate nucleus; IC= internal capsule; LV=lateral ventricle; Put= putamen; R= right side.

Figure 6.

TH+ fiber densities in the caudate nucleus and putamen of parkinsonian animals. No significant difference in TH+ fiber density was found between early stage and late stage parkinsonian animals in both the caudate nucleus and the putamen on the contralateral side of MPTP administration (Open bars in A &B). However, higher doses of MPTP almost completely destroyed all TH+ fibers in these structures (about 1% remained, far right close bars in A&B) while in milder parkinsonian animals (the left close bars) approximately 30% and 25% of TH+ fibers remained in the caudate nucleus and the putamen, respectively. **P<0.01

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by USPHS NIH grants NS39787, AG013494 and NS050242.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Albanese A, Granata R, Gregori B, Piccardi MP, Colosimo C, Tonali P. Chronic administration of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine to monkeys: behavioural, morphological and biochemical correlates. Neuroscience. 1993;55(3):823–832. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90444-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander GM, Schwartzman RJ, Brainard L, Gordon SW, Grothusen JR. Changes in brain catecholamines and dopamine uptake sites at different stages of MPTP parkinsonism in monkeys. Brain. Res. 1992;588(2):261–269. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91584-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen AH, Zhang Z, Zhang M, Gash DM, Avison MJ. Age-associated changes in rhesus CNS composition identified by MRI. Brain. Res. 1999;829(1–2):90–98. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araki T, Sasaki Y, Milbrandt J. Increased nuclear NAD biosynthesis and SIRT1 activation prevent axonal degeneration. Science. 2004;305(5686):1010–1013. doi: 10.1126/science.1098014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballard PA, Tetrud JW, Langston JW. Permanent human parkinsonism due to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP): seven cases. Neurology. 1985;35(7):949–956. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.7.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bankiewicz KS, Oldfield EH, Chiueh CC, Doppman JL, Jacobowitz DM, Kopin IJ. Hemiparkinsonism in monkeys after unilateral internal carotid artery infusion of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) Life Sci. 1986;39:7–16. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90431-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bender K, Newsholme P, Brennan L, Maechler P. The importance of redox shuttles to pancreatic beta-cell energy metabolism and function. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34(pt 5):811–814. doi: 10.1042/BST0340811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohnen NI, Albin RL, Koeppe RA, Wernette KA, Kilbourn MR, Minoshima S, Frey KA. Positron emission tomography of monoaminergic vesicular binding in aging and Parkinson disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26(9):1198–1212. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks DJ, Salmon EP, Mathias CJ, Quinn N, Leenders KL, Bannister R, Marsden CD, Frackowiak RS. The relationship between locomotor disability, autonomic dysfunction, and the integrity of the striatal dopaminergic system in patients with multiple system atrophy, pure autonomic failure, and Parkinson's disease, studied with PET. Brain. 1990;113(Pt 5):1539–1552. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.5.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collier TJ, Lipton J, Daley BF, Palfi S, Chu Y, Sortwell C, Bakay RA, Sladek JR, Jr, Kordower JH. Aging-related changes in the nigrostriatal dopamine system and the response to MPTP in nonhuman primates: diminished compensatory mechanisms as a prelude to parkinsonism. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;26(1):56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crossman AR, Clarke CE, Boyce S, Robertson RG, Sambrook MA. MPTP-induced parkinsonism in the monkey: neurochemical pathology, complications of treatment and pathophysiological mechanisms. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14 3 Suppl:428–435. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100037859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis GC, Williams AC, Markey SP, Ebert MH, Caine ED, Reichert CM, Kopin IJ. Chronic Parkinsonism secondary to intravenous injection of meperidine analogues. Psychiatry Res. 1979;1(3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Degryse AD, Colpaert FC. Symptoms and behavioral features induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) in an old Java monkey [Macaca cynomolgus fascicularis (Raffles)] Brain Res. Bull. 1986;16(5):561–571. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsworth JD, Deutch AY, Redmond DE, Jr, Taylor JR, Sladek JR, Jr, Roth RH. Symptomatic and asymptomatic 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine-treated primates: biochemical changes in striatal regions. Neuroscience. 1989;33(2):323–331. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 5):2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkel E. The mitochondrion: is it central to apoptosis? Science. 2001;292(5517):624–626. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5517.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gash DM, Zhang Z, Ovadia A, Cass WA, Yi A, Simmerman L, Russell D, Martin D, Lapchak PA, Collins F, Hoffer BJ, Gerhardt GA. Functional recovery in parkinsonian monkeys treated with GDNF. Nature. 1996;380(6571):252–255. doi: 10.1038/380252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerhardt GA, Cass WA, Yi A, Zhang Z, Gash DM. Changes in somatodendritic but not terminal dopamine regulation in aged rhesus monkeys. J. Neurochem. 2002;80(1):168–177. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grondin R, Zhang Z, Yi A, Cass WA, Maswood N, Andersen AH, Elsberry DD, Klein MC, Gerhardt GA, Gash DM. Chronic, controlled GDNF infusion promotes structural and functional recovery in advanced parkinsonian monkeys. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 10):2191–2201. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hantraye P, Varastet M, Peschanski M, Riche D, Cesaro P, Willer JC, Maziere M. Stable parkinsonian syndrome and uneven loss of striatal dopamine fibres following chronic MPTP administration in baboons. Neuroscience. 1993;53(1):169–178. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90295-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunot S, Flavell RA. Apoptosis. Death of a monopoly? Science. 2001;292(5518):865–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1060885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irwin I, Delanney L, Chan P, Sandy MS, Di Monte DA, Langston JW. Nigrostriatal monoamine oxidase A and B in aging squirrel monkeys and C57BL/6 mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 1997;18(2):235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jellinger KA. Recent developments in the pathology of Parkinson's disease. J. Neural. Transm. Suppl. 2002;(62):347–376. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6139-5_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakowec MW, Petzinger GM. 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned model of Parkinson's disease, with emphasis on mice and nonhuman primates. Comp Med. 2004;54:497–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Bjorklund A. Preservation of a functional nigrostriatal dopamine pathway by GDNF in the intrastriatal 6-OHDA lesion model depends on the site of administration of the trophic factor. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12(11):3871–3882. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kish SJ, Shannak K, Hornykiewicz O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;318(14):876–880. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804073181402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kish SJ, Tong J, Hornykiewicz O, Rajput A, Chang LJ, Guttman M, Furukawa Y. Preferential loss of serotonin markers in caudate versus putamen in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2008;131:120–131. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraytsberg Y, Kudryavtseva E, McKee AC, Geula C, Kowall NW, Khrapko K. Mitochondrial DNA deletions are abundant and cause functional impairment in aged human substantia nigra neurons. Nat. Genet. 2006;38(5):518–520. doi: 10.1038/ng1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurlan R, Kim M, Gash DM. Time course and magnitude of spontaneous recovery of parkinsonism produced by intracarotid administration of 1-methyl-4- phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine to monkeys. Ann. Neurol. 1991;29(6):677–79. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang AE, Lozano AM. Parkinson's disease. First of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339(15):1044–1053. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang AE, Lozano AM. Parkinson's disease. Second of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339(16):1130–1143. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810153391607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langston JW, Ballard PA., Jr Parkinson's disease in a chemist working with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983;309(5):310. doi: 10.1056/nejm198308043090511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee CS, Schulzer M, de la Fuente-Fernandez R, Mak E, Kuramoto L, Sossi V, Ruth TJ, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ. Lack of regional selectivity during the progression of Parkinson disease: implications for pathogenesis. Arch. Neurol. 2004;61(12):1920–1925. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.12.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayeux R, Marder K, Cote LJ, Denaro J, Hemenegildo N, Mejia H, Tang MX, Lantigua R, Wilder D, Gurland B. The frequency of idiopathic Parkinson's disease by age, ethnic group, and sex in northern Manhattan, 1988–1993. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1995;142(8):820–827. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCormack AL, Di Monte DA, Delfani K, Irwin I, DeLanney LE, Langston WJ, Janson AM. Aging of the nigrostriatal system in the squirrel monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;471(4):387–395. doi: 10.1002/cne.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moratalla R, Quinn B, DeLanney LE, Irwin I, Langston JW, Graybiel AM. Differential vulnerability of primate caudate-putamen and striosome-matrix dopamine systems to the neurotoxic effects of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1992;89(9):3859–3863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mounayar S, Boulet S, Tande D, Jan C, Pessiglione M, Hirsch EC, Feger J, Savasta M, Francois C, Tremblay L. A new model to study compensatory mechanisms in MPTP-treated monkeys exhibiting recovery. Brain. 2007;130:2898–2914. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narabayashi H. Similarity and dissimilarity of MPTP models to Parkinson's disease: importance of juvenile parkinsonism. Eur. Neurol. 1987;26 Suppl 1:24–29. doi: 10.1159/000116352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicklas WJ, Vyas I, Heikkila RE. Inhibition of NADH-linked oxidation in brain mitochondria by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine, a metabolite of the neurotoxin, 1- methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine. Life Sci. 1985;36(26):2503–2508. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ovadia A, Zhang Z, Gash DM. Increased susceptibility to MPTP toxicity in middle-aged rhesus monkeys. Neurobiol. Aging. 1995;16(6):931–937. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)02012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez-Otano I, Oset C, Luquin MR, Herrero MT, Obeso JA, Del Rio J. MPTP-induced parkinsonism in primates: pattern of striatal dopamine loss following acute and chronic administration. Neurosci. Lett. 1994;175(1–2):121–125. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)91094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petzinger GM, Langston JW. Vol.1 Parkinson’s Disease. Chapter 4. The MPTP-Lesioned Non-Human Primate: A Model for Parkinson’s Disease. Scottsdale: Prominent Press; 1998. Advances in Neurodegenerative Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pifl C, Schingnitz G, Hornykiewicz O. The neurotoxin MPTP does not reproduce in the rhesus monkey the interregional pattern of striatal dopamine loss typical of human idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 1988;92(2):228–233. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pifl C, Schingnitz G, Hornykiewicz O. Effect of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine on the regional distribution of brain monoamines in the rhesus monkey. Neuroscience. 1991;44(3):591–605. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pifl C, Hornykiewicz O. Dopamine turnover is upregulated in the caudate/putamen of asymptomatic MPTP-treated rhesus monkeys. Neurochem. Int. 2006;49(5):519–524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Przedborski S, Tieu K, Perier C, Vila M. MPTP as a mitochondrial neurotoxic model of Parkinson's disease. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2004;36(4):375–379. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041771.66775.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramsay RR, Salach JI, Singer TP. Uptake of the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridine (MPP+) by mitochondria and its relation to the inhibition of the mitochondrial oxidation of NAD+-linked substrates by MPP+ Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986;134(2):743–748. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rose S, Nomoto M, Jackson EA, Gibb WR, Jaehnig P, Jenner P, Marsden CD. Age-related effects of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine treatment of common marmosets. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;230(2):177–185. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90800-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sasaki Y, Araki T, Milbrandt J. Stimulation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biosynthetic pathways delays axonal degeneration after axotomy. J. Neurosci. 2006;26(33):8484–8491. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2320-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider JS, Yuwiler A, Markham CH. Selective loss of subpopulations of ventral mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons in the monkey following exposure to MPTP. Brain Res. 1987;411(1):144–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smigrodzki R, Parks J, Parker WD. High frequency of mitochondrial complex I mutations in Parkinson's disease and aging. Neurobiol. Aging. 2004;25(10):1273–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soderstrom K, O'Malley J, Steece-Collier K, Kordower JH. Neural repair strategies for Parkinson's disease: insights from primate models. Cell Transplant. 2006;15:251–265. doi: 10.3727/000000006783982025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trimmer PA, Swerdlow RH, Parks JK, Keeney P, Bennett JP, Jr, Miller SW, Davis RE, Parker WD., Jr Abnormal mitochondrial morphology in sporadic Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease cybrid cell lines. Exp. Neurol. 2000;162(1):37–50. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walton A, Branham A, Gash DM, Grondin R. Automated video analysis of age-related motor deficits in monkeys using EthoVision. Neurobiol. Aging. 2006;27(10):1477–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Z, Andersen AH, Ai Y, Loveland A, Hardy PA, Gerhardt GA, Gash DM. Assessing nigrostriatal dysfunctions by pharmacological MRI in parkinsonian rhesus macaques. Neuroimage. 2006;33:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]