Abstract

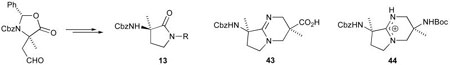

Several functionalized diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonenes and other heterocycles have been prepared as potential peptidomimetic scaffolds. A novel and efficient method has been developed for the preparation of N-substituted γ-lactams 13. Preparation of amidine-containing 1,5-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonenes 43 and 44 has been achieved through Hg-mediated cyclization of the precursor N-aminopropyl-γ-thiolactams and subsequent functional group manipulation. Bicycle 43 represents a novel scaffold for potential peptide turn mimetics, whereas 44 could potentially be employed as an α-helix template attached to the C-terminus of peptides. These compounds are novel additions to the current range of small-molecule constrained peptidomimetics.

Keywords: Peptidomimetic; Diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonene; Pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrimidine; β-turn mimetic; α-helix template

Introduction

Functionalized monocyclic and bicyclic compounds are highly useful scaffolds in the rational design and synthesis of peptidomimetics.1-5 These conformationally restricted heterocyclic frameworks have been used to generate mimics and templates of a variety of peptide secondary structural elements, particularly β-turns,6-17 but also γ-turns,18-20 β-strands21-26 and α-helices.27-31 Such scaffolds have been employed to constrain the backbone geometry and/or side-chain conformations of appended peptides to investigate the structural basis of peptide–protein and protein–protein interactions, and to develop potent and selective peptidomimetic therapeutic agents. Notable examples of constrained cyclic peptidomimetic scaffolds include the 6,5-fused azabicycloalkane–type β-turn mimetics, exemplified by the Nagai mimetic 1 (X=CH2, Y=S),32 5,6-fused bicyclic hydrazones, e.g. 2,23,33 diketopiperazine β-turn mimetics 3,8,12,13,15 the aza[4.3.0]bicyclononene and diproline-based α-helix templates, 427 and 5,28,29 respectively, medium-ring β-turn mimetics, e.g. 6,3,9,10,17 γ-lactam-constrained dipeptide surrogates 7,1,34 and the β-strand templates 821,22 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cyclic small molecule peptidomimetic scaffolds

We were interested in expanding the range of fused 5,6-bicyclic heterocycles available as peptidomimetic scaffolds. The diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonene 9 represents such a novel peptidomimetic scaffold, in which incorporation of a carboxylate substituent (R2 = CO2H) affords a dipeptide surrogate that could act as a turn mimetic. Alternatively, incorporation of an amino substituent (R2 = NH2) affords a potential α-helix template related to the N-terminal α-helix template 4 developed by Bartlett.27 Bicyclic amidine 9 (R2 = NH2), in the protonated state, has a geometry matching that of 4 but with the three hydrogen-bond acceptor carbonyl groups replaced with donor N–H groups, and represents a potential C-terminal α-helix template.

Results and Discussion

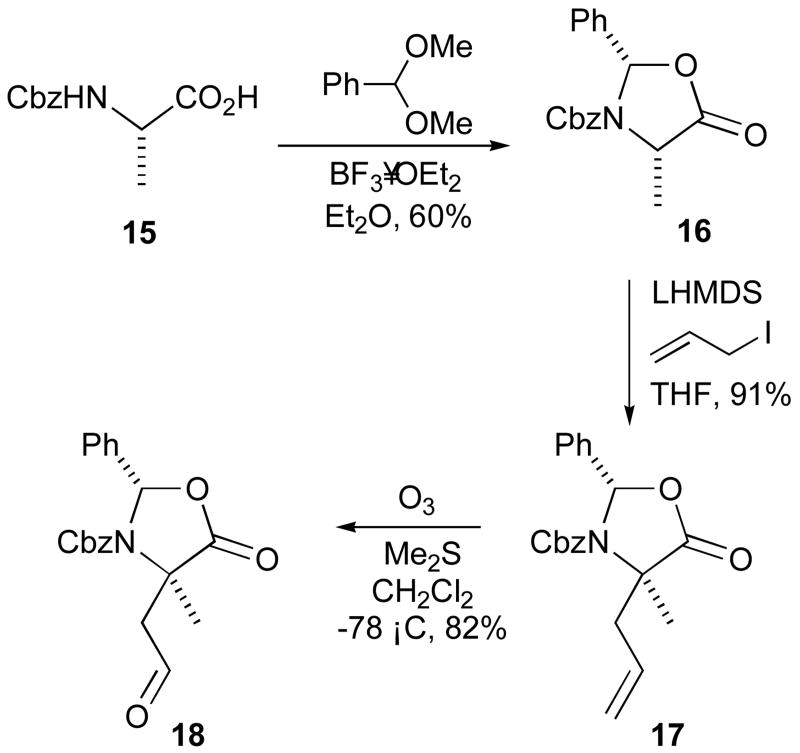

Retrosynthetic analysis of the bicyclic amidine 9 suggested that the bicycle could be formed by cyclodehydration of an N-(3-aminopropyl)-γ-lactam 10 (Scheme 1).35 While Freidinger1 has developed methods for the preparation of γ-lactam peptidomimetics, we envisaged a novel route to the γ-lactam 10 through reductive amination of an aspartate-semi aldehyde derivative 11 with amine 12, followed by cyclization. Alternatively, 10 could be accessed by Michael-type addition of γ-lactam 13 to substituted acrylate 14. With the γ-lactam 13 accessible from 11 through a similar reductive amination–cyclization process, and the amine 12 accessible from acrylate 14, the required starting materials for this strategy are the aldehyde 11 and acrylate 14. We chose to incorporate α-methyl substituents (9 R1, R3 = Me) for additional conformational constraint. Accordingly, our synthesis was initiated with oxazolidinone 16, prepared via condensation of Cbz-L-alanine 15 with benzaldehyde dimethyl acetal according to Shrader's modification36 of the procedure of Karady et al.37 Alkylation of the oxazolidinone 16 was achieved in 91% yield by treatment with lithium hexamethyldisilazide followed by addition of allyl iodide (Scheme 2). Only the (2S,4S)-isomer was detected by 1H NMR spectroscopy, indicating that the reaction had proceeded to give the allyloxazolidinone 17 in >95:5 diastereomeric ratio. Ozonolysis of the allyloxazolidinone 17 gave the requisite aldehyde 18 in 82% yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1.

Scheme 2.

A. Preparation of γ-Lactam

A reductive amination/cyclization strategy from 18 was investigated as a route to γ-lactam scaffolds. Treatment of the aldehyde 18 with ammonium chloride and sodium cyanoborohydride gave the γ-lactam 20 directly, presumably via cyclization of intermediate amine 19 with concomitant release of benzaldehyde (Scheme 3). However, the γ-lactam 20 was produced in low yield, with the N-benzyl lactam 21 isolated as the major product. The N-benzyl lactam 21 presumably forms by reductive amination of the benzaldehyde byproduct generating benzylamine, which then undergoes reductive amination/cyclization with aldehyde 18. An efficient preparation of the lactam 20 was ultimately achieved using p-anisidine as the amine partner in the reductive amination of 18. Under these conditions PMP-lactam 22 was produced in 90% yield, which upon treatment with ceric ammonium nitrate gave γ-lactam 20 in good yield (Scheme 4).

Scheme 3.

Scheme 4.

B. Synthesis of diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonene ring system

Extension of the reductive amination/cyclization methodology was then investigated using functionalized diamines as a route toward the diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonene ring system. Treatment of the aldehyde 18 with Boc-diaminopropane 23 under reductive amination conditions gave the bicyclic compound 24 in 52% yield, as a 1:1 ratio of diastereomers (Scheme 5). Formation of the bicyclic compound 24 presumably occurs via the initially formed iminium species 25, with two cyclization events and elimination of benzaldehyde yielding the bicyclic product 24.

Scheme 5.

It was anticipated that replacement of Boc-protected diamine 23 with the corresponding phthaloyl-protected compound 26 would prevent intramolecular attack of the intermediate iminium species, thereby preventing formation of the bicyclic compound. Accordingly, treatment of the aldehyde 18 with 1.5 equivalents of the phthaloyl-protected diaminopropane 26 in the presence of sodium cyanoborohydride gave the phthalimidopropyl-γ-lactam 27 in 75% yield (Scheme 6). A slight excess of amine 26 is required for optimum yields of 27, as some of the amine undergoes reductive amination with the benzaldehyde byproduct formed concurrently with production of the γ-lactam 27.

Scheme 6.

Removal of the phthaloyl group from 27 was effected by treatment with hydrazine hydrate in ethanol, to generate the amine 28. Subsequent attempts to cyclodehydrate the aminopropyl-γ-lactam 28 to the bicyclic amidine 29, including refluxing in high boiling point solvents with catalytic acid, and via the corresponding O-silyl- and O-alkyl-imidates, were unsuccessful.35 Accordingly, γ-lactam 27 was converted to the corresponding thiolactam 30 by treatment with Lawesson's reagent.38 The phthalimidopropyl thiolactam 30 was isolated in moderate yield, together with varying amounts of a byproduct, presumed to be the dithio-compound 31 (Scheme 7). Various conditions were employed in an attempt to improve the yield of the thiolactam 30, however variation of the amount of Lawesson's reagent and the reaction time did not result in significant improvements in the yield of 30 (optimum 40%, with 20% unreacted starting material). Treatment of the thiolactam 30 with hydrazine hydrate gave the free amine 32 in 77% yield. The amine was then treated with mercuric chloride in THF34,39 to give the bicyclic amidine 29 in 67% yield. The amidine 29 was found to be unstable as its free base, and was therefore purified and stored as its trifluoroacetate salt.

Scheme 7.

C. Synthesis of functionalized diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonene ring system

With a method for preparing the alanine-derived diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonene derivative 29 in hand, preparation of the carboxylate-functionalized bicycle 41via the corresponding carboxylate-functionalized phthalimidopropyl-γ-lactam 37 was investigated. Initial attempts to prepare 37 by Michael-type addition of γ-lactam 20 to phthalimidomethacrylate 34 were unsuccessful. Hence, the reductive amination–cyclization route was followed as for the preparation of amidine 29, which necessitated preparation of amine 36. Phthalimidomethylacrylate 34 was prepared from the corresponding bromide 33, then was treated with one equivalent of benzylamine to give the amine 35 in 57% yield (76% based on recovered starting material) (Scheme 8). Use of excess benzylamine in attempts to increase the yield of the amine 35 only resulted in the formation of increasing amounts of N-benzylphthalimide, presumably via transimidation of either the acrylate 34 or the amine 35 with excess benzylamine.

Scheme 8.

Removal of the benzyl group from the amine 35 was initially attempted by hydrogenation in the presence of Pearlman's catalyst, however, the procedure was not reproducible and normally resulted in the recovery of the benzyl-protected amine 35. Alternative debenzylation conditions were therefore investigated, and ultimately treatment of the N-benzylamine 35 with N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) or bromine in methylene chloride/water was found to give the amine as its hydrobromide salt 36, in high yield (Scheme 8).40 While N-debenzylation under these conditions has been employed sporadically, the use of this procedure is most common with N-benzylamides,41,42 with the N-debenzylation of amines40,43 – particularly secondary amines44 – being rare. The use of NBS and bromine were equally effective, with the use of bromine being the method of choice on large scale as removal of the succinimide byproduct is avoided.

Synthesis of the bicyclic amidine 41 then followed the protocol outlined in Scheme 7 for the synthesis of the model compound 29. Reductive amination of the aldehyde 18 with the amine hydrobromide salt 36 gave the γ-lactam 37 in 71% yield, as a 1:1 ratio of diastereomers. The diastereomers were separable by chromatography and independently characterized, but in subsequent reactions a 1:1 mixture of the diastereomers of 37 was employed. As with the conversion of aldehyde 18 and amine 26 to give γ-lactam 27 (Scheme 6), conversion of 18 and amine 36 to give γ-lactam 37 required an excess of the amine due to the competing reductive amination with the benzaldehyde byproduct (Scheme 9). It should be noted, however, that in this case this secondary reductive amination process converts excess amine 36 into its corresponding N-benzyl derivative 35, which is the immediate precursor of the amine 36. The use of 1.5 equivalents of amine 36 in the reductive amination of 18 gave, in addition to 81% yield of the desired lactam 37, the N-benzylamine 35 in 24% yield (72% recovery of excess amine, which can be recycled back to the amine 36 thereby improving the overall efficiency of the process).

Scheme 9.

Formation of the thiolactam 38 was performed by treatment of the γ-lactam 37 with 0.55 equivalents of Lawesson's reagent in refluxing toluene (Scheme 9). The thiolactam 38 was isolated in 56% yield, and the dithio compound 39 in 10% yield. The yield of the thiolactam 38 was higher than for the corresponding reaction in the model series (27→30), presumably because the methoxycarbonyl group sterically shields the phthaloyl group, thereby slowing formation of the dithio compound 39.

Initial attempts to remove the phthaloyl group of 38 by hydrazinolysis with hydrazine hydrate in refluxing ethanol were unsuccessful, and the starting material was recovered. After experimentation with various methods it was found that treatment of the thiolactam 38 with anhydrous hydrazine in methanol gave a satisfactory yield of the free amine 40.

With the functionalized aminopropyl-thiolactam 40 in hand, synthesis of the bicylic amidine was investigated. Treatment of the thiolactam 40 with mercuric chloride in refluxing THF proceeded slowly, with some starting material still remaining after two days. Dioxane was therefore substituted for THF, and the corresponding reaction using dioxane as solvent was found to be complete in 24 hours (Scheme 9). Purification of the amidine 41 proved troublesome, with the solvent system used in chromatographic purification of the model amidine 29 (CHCl3/MeOH/TFA) proving ineffective. The dilemma was solved through the use of either reverse-phase column chromatography, or normal phase silica chromatography eluting with CH2Cl2/MeOH/isopropylamine, with the amidine 41 isolated in 62% yield as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers (Scheme 9).

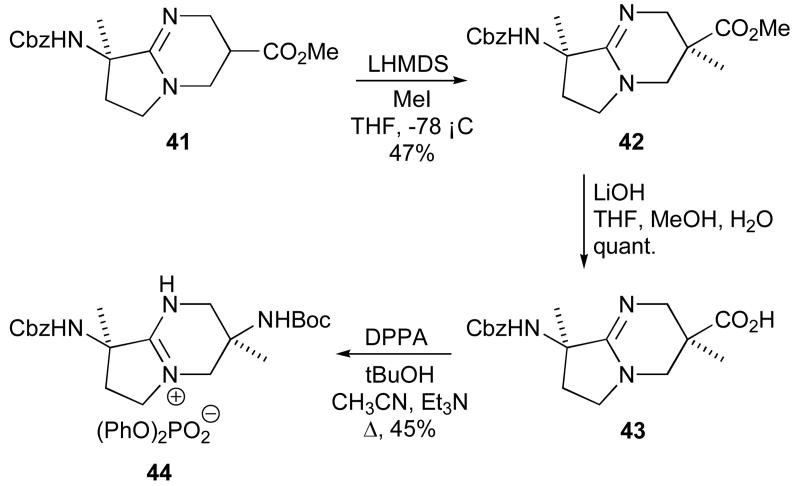

Alkylation of the amidine 41 adjacent to the ester moiety was then investigated in order to introduce further conformational restraint to the bicyclic scaffold.27 Treatment of the amidine 41 with 5.5 equivalents of LHMDS and 3.5 equivalents of methyl iodide gave a moderate yield of the alkylated compound 42 (Scheme 10). Only one diastereomer was detectable by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude product, indicating that the reaction proceeds stereoselectively to give 42 in > 95:5 diastereomeric ratio. While the stereochemical identity of the product was not established definitively, it is presumed to arise from approach of the electrophile from the side opposite to the bulky, pseudo-axial CbzNH-group. This is also in accord with the reported α-methylations of cyclohexane carboxylate esters in which the methyl groups are installed in a cis-manner in equatorial positions.45

Scheme 10.

Alkaline hydrolysis of ester 42 gave the corresponding acid 43 in quantitative yield. Acid 43 was then transformed through a Curtius rearrangement to the corresponding Boc-protected amine 44, isolated in good yield as the diphenylphosphate salt.

Conclusion

Several functionalized diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonenes and other heterocycles have been prepared as peptidomimetic scaffolds. A novel and efficient method has been developed for the preparation N-substituted γ-lactams, which have previously been utilized as constrained dipeptide surrogates. A rapid assembly of the 1,5-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonan-9-one ring system 24 has been achieved through a one-pot reductive amination-tandem cyclization process. Preparation of amidine-containing 1,5-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonenes 29 and 41–44 has been achieved through Hg-mediated cyclization of the precursor N-aminopropyl-γ-thiolactams and subsequent functional group manipulation. C3-Carboxylate-functionalized compound 43, containing a fused 5,6-bicyclic ring system and the combination of a protected amino group and carboxylic acid, represents a novel scaffold for potential peptide turn mimetics. C3-Amino-functionalized compound 44, containing a protonated amidine and two differentially-protected amino groups, could potentially be employed as an α-helix template attached to the C-terminus of peptides. The three N–H hydrogen bond donors of 44 are positioned in an analogous arrangement to the three carbonyl group hydrogen bond acceptors of the N-terminal template 4, and therefore mimics the hydrogen-bonding pattern of the first turn at the C-terminus of an α-helix. These compounds are novel additions to the current range of small-molecule constrained peptidomimetics.

Experimental Section

General procedures are available in the Supporting Information.

(2S,4S)-3-Benzyloxycarbonyl-4-methyl-2-phenyl-4-(prop-2-enyl)oxazolidin-5-one 17

A solution of the oxazolidinone 1636 (15.0 g, 48.2 mmol) in dry THF (80 mL), under an atmosphere of argon, was cooled to −78 °C. A solution of lithium hexamethyldisilazide in THF (1.0M, 63 mL) was added slowly and the mixture was stirred for 15 min. Allyl iodide (6.3 mL, 68.9 mmol), which had been passed through a short column of alumina, was then added and the mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 3 h. The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and was stirred for a further 18 h. The mixture was diluted with ether (250 mL), and was quenched by the addition of sat. NH4Cl (250 mL). The organic layer was separated and was washed with sat. NH4Cl. The combined aqueous layers were extracted with ether, then the organic layers were combined, dried, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by chromatography on silica to give the oxazolidinone 17 (15.45 g, 91%) as a clear, viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) (major rotamer) δ̱ 1.81 (3H, s), 2.54 (1H, dd, J 6.3 13.5), 3.27 (1H, dd, J 8.9 13.5), 4.96 (2H, m), 5.16 (2H, m), 5.67 (1H, m), 6.28 (1H, s, NH), 6.87 (1H, m), 7.18–7.41 (9H, m); (minor rotamer) δ 1.72 (3H, s), 2.54 (1H, dd, J 6.3 13.5), 2.92 (1H, dd, J 8.5 13.5), 4.96 (2H, m), 5.16 (2H, m), 5.60 (1H, m), 6.34 (1H, s, NH), 6.87 (1H, m, ArH), 7.18–7.41 (9H, m, ArH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 23.6, 39.4, 63.1, 67.2, 89.4, 121.3, 126.8, 127.8, 128.1, 128.3, 128.7, 129.8, 130.9, 135.2, 137.0, 151.7, 174.1. MS (FAB) m/z 352 (100%, M+H+).

(2S,4S)-3-Benzyloxycarbonyl-4-methyl-4-(2-oxoethyl)-2-phenyloxazolidin-5-one 18

A solution of the allyloxazolidinone 17 (7.8 g, 22.2 mmol) in methylene chloride (200 mL) was cooled to −78 °C, then ozone was bubbled through the solution until it turned blue (ca. 45 min). Oxygen was bubbled through the solution until it became colourless. Dimethyl sulfide (33 mL) was added, and the solution was stirred at −78 °C for 30 min. The solution was allowed to warm to room temperature, then the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by chromatography on silica and was recrystallized from hexanes/ethyl acetate to give the aldehyde 18 (6.44 g, 82%) as colourless prisms. M.p. 109–110 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) (major rotamer) δ 1.76 (3H, s), 3.07 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 4.04 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), 4.84 (1H, d, J = 9.9 Hz), 4.97 (1H, d, J = 9.9 Hz), 6.57 (1H, s), 6.79 (1H, m), 7.16–7.48 (9H, m), 9.92 (1H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) (major rotamer) δ 24.4, 48.4, 57.8, 67.3, 89.9, 127.1, 127.5, 128.0, 128.3, 128.6, 129.8, 135.1, 136.6, 151.8, 173.6, 198.6. MS (FAB) m/z 354 (100%, M+H+). Anal. Calcd for C20H19NO5: C 68.0, H 5.4, N 4.0. Found: C 68.0, H 5.5, N 4.1.

(3R)-3-Benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-methyl-1-(3-phthalimidopropyl)pyrrolidin-2-one 27

To a solution of the aldehyde 18 (1.0 g, 2.83 mmol) and the amine salt 26 (1.35 g, 4.25 mmol) in methanol (25 mL) was added NaCNBH3 (267 mg, 4.25 mmol) and NaOAc (100 mg). Acetic acid was added dropwise to lower the pH to 6.0. The solution was then stirred at room temperature for 36 h, then the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was taken up in ether/methylene chloride (5:1) and was washed with water, then dilute HCl, then with water. The organic phase was dried and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Purification of the residue by chromatography on silica gave the lactam 27 (0.92 g, 75%) as a colorless oil, which solidified after storage at −20 °C. M.p. 73–75 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.41 (3H, s), 1.93 (1H,m), 1.97 (1H, m), 2.35 (1H, m), 2.45 (1H, m), 3.32 (1H, m), 3.39 (2H, m), 3.48 (1H, m), 3.66 (1H, m), 3.71 (1H, m), 5.04 (1H, d, J = 12.2 Hz), 5.09 (1H, d, J = 12.2 Hz), 5.42 (1H, br s), 7.32 (5H, m), 7.71 (2H, m), 7.83 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.2, 25.9, 32.7, 35.3, 40.5, 43.4, 57.8, 66.4, 123.1, 127.8, 127.9, 128.3, 132.0, 133.9, 136.3, 154.9, 168.0, 174.5. Anal. Calcd for C24H25N3O5: C 66.2, H 5.8, N 9.7. Found: C 66.5, H 6.0, N 9.9.

(3R)-3-Benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-methyl-1-(3-phthalimidopropyl)pyrrolidin-2-thione 30

To a solution of the lactam 27 (400 mg, 0.92 mmol) in dry toleune (5 mL) was added Lawesson's reagent (124 mg, 0.31 mmol), and the mixture was heated at reflux for 2 h. The mixture was cooled and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was chromatographed on silica to give the dithio-compound 31 (28 mg, 7%) and the thiolactam 30 (165 mg, 40%) as a white solid. M.p. 55–57 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.45 (3H, s), 2.07 (2H, m), 2.42 (1H, m), 2.61 (1H, m), 3.70 (4H, m), 3.74 (1H, m), 3.97 (1H, m), 5.07 (2H, s), 6.00 (1H, s), 7.28–7.35 (5H, m), 7.72 (2H, m), 7.83 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.6, 25.3, 34.2, 35.2, 45.9, 51.4, 66.3, 66.6, 123.2, 127.8, 127.9, 128.4, 131.9, 134.0, 136.4, 154.7, 168.1, 204.1. Anal. Calcd for C24H25N3O4S: C 63.8, H 5.6, N 9.3. Found: C 64.1,H 5.8, N 9.5.

(3R)-1-(3-Aminopropyl)-3-benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-methylpyrrolidin-2-thione 32

To a solution of the thiolactam 30 (1.1 g, 2.4 mmol) in ethanol (20 mL) was added a solution of hydrazine hydrate in ethanol (2M, 2.4 mL). The solution was heated at reflux for 2.5 h, then was allowed to cool and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was suspended in dilute HCl (30 mL), and the mixture was heated at 50° for 15 min. The mixture was cooled and the precipitate was removed by filtration. The filtrate was washed with methylene chloride, then the aqueous layer was made basic (pH >11) by the addition of 6N NaOH. The solution was extracted twice with ethyl actetate, then the combined organic phases were dried and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, to give the amine 32 (605 mg, 77%) as a pale yellow oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.41 (3H, s), 1.67 (2H, br s), 1.77 (2H, m), 2.41 (1H, m), 2.49 (1H, m), 2.67 (2H, m), 3.56 (1H, m), 3.63 (1H, m), 3.78 (1H, m), 3.86 (1H, m), 5.07 (2H, s), 6.21 (1H, br s), 7.31 (s, 5H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.9, 27.9, 33.8, 37.9, 45.7, 51.4, 66.4, 66.8, 127.9, 128.0, 128.4, 136.3, 154.8, 204.0. MS (FAB) m/z 322 (100%, M+H+).

(S)-7-Amino-7-methyl-1,5-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]non-5-ene 29

To a solution of the amine 32 (600 mg, 1.87 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL) was added HgCl2 (760 mg, 2.80 mmol). The mixture was heated at reflux for 18 h, then the mixture was filtered and the filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by chromatography on silica, eluting with CHCl3/MeOH/TFA (70:30:1) to give the bicyclic amidine 29 as its trifluoroacetate salt (502 mg, 67%) as a clear oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.64 (3H, s), 2.02 (2H, m), 2.09 (1H, m), 2.75 (1H, m). 3.39 (2H, m), 3.44 (2H, m), 3.63 (1H, m), 3.80 (1H, m), 5.02 (1H, d, J = 12.5 Hz), 5.10 (1H, d, J = 12.5 Hz), 7.32 (5H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 18.4, 24.7, 32.8, 38.0, 43.3, 51.2, 61.3, 67.0, 127.6, 128.0, 128.4, 136.2, 156.8, 167.3. MS (FAB) m/z 288 (100%, M+H+). HRMS (FAB) m/z 288.1704, C16H22N3O2 requires 288.1712.

Methyl 3-Benzylamino-2-(phthalimidomethyl)propanoate 35

To a solution of the acrylate 3446 (5.0 g, 20.4 mmol) in chloroform (25 mL) was added benzylamine (2.2 g, 20.5 mmol). The solution was refluxed for 2 d, then was cooled and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. Purification of the residue by chromatography on silica recovered some acrylate 34 (1.23 g, 25%) and gave the amine 35 (4.42 g, 57%) as a white solid. M.p. 82–83 °C. IR ν 3470, 3326, 1773, 1734, 1715, 1398, 1367, 1201 cm-1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.81 (1H, br s), 2.83 (1H, dd, J = 5.7, 12.3 Hz), 2.89 (1H, dd, J = 6.7, 12.3 Hz), 3.03 (1H, m), 3.67 (3H, s), 3.77 (2H, s), 3.97 (1H, dd, J = 6.7, 14.0 Hz), 4.00 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 14.0 Hz), 7.20 (1H, m), 7.27 (4H, m), 7.71 (2H, m), 7.83 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDC13) δ 37.3, 44.5, 47.7, 51.9, 53.6, 123.3, 126.8, 128.0, 128.2, 131.9, 133.4, 140.0, 168.1, 173.0. MS (FAB) m/z 353 (100%, M+H+). Anal. Calcd for C20H20N2O4: C 68.2, H 5.7, N 8.0. Found: C 68.1, H 5.9, N 7.8.

Methyl 3-Amino-2-(phthalimidomethyl)propanoate Hydrobromide 36

To a solution of the amine 35 (23.0 g, 65.3 mmol) in methylene chloride (300 mL) was added water (40 mL) and the mixture was stirred vigorously. Bromine (11.0 g, 68.8 mmol) in methylene chloride (60 mL) was added dropwise over ca. 30 min., after which vigorous stirring was continued for 4 h. The mixture was extracted with water (300 mL), and the aqueous layer was lyophilized to give the amine salt 36 (20.4 g, 91%) as a white powder. Recrystallization from ether/methanol gave the amine salt 36 as fine crystals. M.p. 184–186 °C (decomp.). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 3.33 (2H, m), 3.42 (1H, m), 3.78 (3H, s), 4.00 (1H, dd, J = 5.4 14.7 Hz), 4.07 (1H, dd, J = 6.3 14.7 Hz), 7.83 (4H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O) δ 37.0, 38.0, 42.1, 53.2, 123.6, 130.8, 135.1, 170.0, 172.6. MS (FAB) m/z 263 (100%, M+H+). Anal. Calcd for C13H15BrN2O2: C 45.5, H 4.4, N 8.2. Found: C 45.7, H 4.5, N 8.0.

(3R)-3-Benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-methyl-1-((2RS)-2-methoxycarbonyl-3-phthalimido)-propyl)pyrrolidin-2-one 37

To a solution of the aldehyde 18 (13.7 g, 38.8 mmol) in methanol (250 mL) was added the amine salt 36 (20.0 g, 58.3 mmol) and sodium cyanoborohydride (3.7 g, 58.9 mmol). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 3 d, with acetic acid being added to keep pH ∼ 6 (ca. 2 mL). The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the residue was partitioned between ethyl acetate and water, and the aqueous phase was re-extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were dried, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was subject to chromatography on silica, eluting with 3:1 ethyl acetate/hexanes, to give the N-benzylamine 35 (4.85 g, 24%), and the lactam 37 (15.5 g, 81%) as a foam, as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers. Further chromatography enabled isolation of pure samples of each of the diastereomers of 37. The first eluting diastereomer was obtained as a glassy solid: M.p. 66–71 °C. IR ν 3420, 3403, 1774, 1718 (br), 1503, 1398, 1072 cm-1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.41 (3H, s), 2.33 (1H, m), 2.46 (1H, m), 3.19 (1H, m), 3.35 (2H, m), 3.48 (1H, dd, J = 8.4, 17.1 Hz), 3.68 (3H, s), 3.74 (1H, dd, J = 5.1, 14.1 Hz), 3.88 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 14.0 Hz), 4.02 (1H, dd, J = 8.3, 14.1 Hz), 5.05 (1H, d, J = 12.3 Hz), 5.08 (1H, d, J = 12.3 Hz), 5.42 (1H, br s), 7.32 (5H, m), 7.72 (2H, m), 7.84 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.2, 32.9, 37.2, 42.7 (2 C's), 44.4, 52.4, 57.7, 66.5, 123.4, 127.9, 128.0, 128.4, 131.8, 134.1, 136.3, 154.9, 167.9, 172.0, 175.0. MS (FAB) m/z 494 (100%, M+H+). Anal. Calcd for C26H27N3O7•0.5H2O: C 62.1, H 5.6, N 8.4. Found: C 62.4, H 5.7, N 8.1. The second eluting diastereomer was obtained as a viscous oil. IR ν 3423, 3405, 1775,1718 (br), 1503, 1399, 1075 cm-1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.37 (3H, s), 2.31 (1H, m), 2.43 (1H, m), 3.30 (2H, m), 3.45 (1H, m), 3.61 (2H, m), 3.67 (3H, s), 3.87 (1H, dd, J = 5.1, 13.0 Hz), 4.00 (1H, dd, J = 7.5, 13.0 Hz), 5.04 (1H, d, J = 12.3 Hz), 5.05 (1H, d, J = 12.3 Hz), 5.36 (1H, br s), 7.32 (5H, m), 7.71 (2H, m), 7.84 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.1, 30.8, 37.3, 42.4, 42.8, 44.0, 52.3, 57.7, 66.5, 123.4, 127.9, 128.0, 128.4, 131.8, 134.1, 136.3, 154.9, 167.9, 171.9, 174.9. MS (FAB) m/z 494 (100%, M+H+).

(3R)-3-Benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-methyl-1-((2RS)-2-methoxycarbonyl-3-phthalimido)-propyl)pyrrolidin-2-thione 38

To a solution of the lactam 37 (1:1 mixture of diastereomers) (11.6 g, 23.5 mmol) in toluene (250 mL) was added Lawesson's reagent (5.4 g, 13.4 mmol). The mixture was refluxed for 1.5 h, then was allowed to cool and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Chromatography of the residue on silica, eluting with 3:2 ethyl acetate/hexanes, gave the dithio compound 39 (1.2 g, 10%), the starting lactam 37 (2.8 g, 24%) and the thiolactam 38 (6.7 g, 56%, 74% based on recovered starting material) as a white foam, as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers. IR ν 3433, 3360, 1774, 1720 (br), 1511, 1496, 1398, 1088 cm-1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.40 (1.5H, s), 1.41 (1.5H, s), 2.38 (1H, m), 2.55 (1H, m), 3.48 (0.5H, m), 3.62 (2.5H, m), 3.69 (1.5H, s), 3.70 (1.5H, s), 3.84 (1H, m), 3.91 (1H, m), 4.03 (1.5H, m), 4.40 (0.5H, m), 5.05 (2H, s), 5.95 (0.5H, br s), 6.00 (0.5H, br s), 7.30 (5H, m), 7.71 (2H, m), 7.83 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 20.8, 24.3, 24.5, 34.2, 34.3, 37.0, 37.2, 41.7, 47.5, 47.6, 52.3, 52.6, 66.1, 66.4, 123.2, 127.7, 127.8, 128.2, 131.6, 134.0, 136.2, 154.5, 167.8, 171.8, 204.7. MS (FAB) m/z 510 (100%, M+H+). Anal. Calcd for C26H27N3O6S: C 61.3, H 5.3, N 8.2. Found: C 61.6, H 5.7, N 7.8.

(3R)-3-Benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-methyl-1-((2RS)-3-amino-2-methoxycarbonyl)-propyl)pyrrolidin-2-thione 40

To a solution of the thiolactam 38 (6.44 g, 12.7 mmol) in dry methanol (80 mL) was added anhydrous hydrazine (445 mg, 13.9 mmol). The solution was stirred under argon at room temperature for 24 h, after which time a white precipitate had formed. The precipitate was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was partitioned between methylene chloride and 2N HCl. The aqueous layer was made basic (pH 10) by the addition of 6N NaOH, then was then extracted with methylene chloride. The combined organic phases were dried and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give the amine 40 (3.27 g, 68%) (1:1 mixture of diastereomers) as a pale yellow oil. IR ν 3431, 3356, 1717 (br), 1515, 1497, 1443, 1088 cm-1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.40 (1.5H, s), 1.42 (1.5H, s), 1.47 (2H, br s), 2.41 (1H, m), 2.52 (1H, m), 2.87 (0.5H, m), 2.95 (1H, m), 3.00 (1H, m), 3.09 (0.5H, m), 3.63 (2H, m), 3.70 (1.5H, s), 3.72 (1.5H, s), 3.74 (0.5H, m), 3.95 (0.5H, dd, J = 7.6, 13.4 Hz), 4.06 (0.5H, m), 4.25 (0.5H, dd, J = 6.6, 13.4 Hz), 5.07 (2H, s), 6.01 (0.5H, br s), 6.05 (0.5H, br s), 7.33 (5H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.6, 34.0, 34.1, 41.1, 41.2, 45.0, 45.3, 47.3, 47.5, 52.0, 52.1, 52.7, 66.3, 66.5, 66.6, 127.8, 127.9, 128.3, 136.2, 154.6, 173.1, 173.3, 204.4, 204.7. MS (FAB) m/z 380 (100%, M+H+). HRMS (FAB) m/z 380.1650, C18H26N3O4S requires 380.1644.

(3RS,7S)-7-Benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-methoxycarbonyl-7-methyl-1,5-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]non-5-ene 41

To a solution of the amine 40 (1.0 g, 2.6 mmol) in dioxane (25 mL) was added mercuric chloride (1.07 g, 3.9 mmol). The mixture was stirred at reflux for 24 h, then was allowed to cool to room temperature. The mixture was filtered through celite, washed with acetone, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by chromatography on silica, eluting with a gradient of CH2Cl2/MeOH/isopropylamine (90:10:1–80:20:1), to give the bicyclic amidine 41 (567 mg, 62%) as a colorless oil. Further chromatography enabled isolation of pure samples of each of the diastereomers of amidine 41. The first eluting diastereomer was obtained as a colorless oil: IR ν 3408, 3275, 1738, 1717, 1692, 1508, 1310, 1275, 1089 cm-1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 1.66 (3H, s), 2.16 (1H, ddd, J = 2.9, 7.9, 12.7 Hz), 2.61 (1H, ddd, J = 8.8, 9.2, 12.7 Hz), 3.22 (1H, m), 3.64 (2H, m), 3.70 (3H, s), 3.79 (4H, m), 5.06 (1H, d, J = 12.7 Hz), 5.12 (1H, d, J = 12.7 Hz), 7.28 (1H, m), 7.35 (2H, m), 7.44 (2H, m), 7.74 (1H, br s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 23.2, 32.9, 34.2, 39.5, 44.5, 50.7, 52.0, 61.3, 66.0, 127.5, 127.6, 128.3, 137.0, 155.4, 166.2, 170.5. MS (FAB) m/z 346 (100%, M+H+). HRMS (FAB) m/z 346.1773, C18H24N3O4 requires 346.1767. Anal. Calcd for C18H23N3O4•HCl•2H2O: C 51.7, H 6.8, N 10.1. Found: C 51.7, H 6.7, N 10.4. The latter eluting diastereomer was obtained as a colorless oil; IR ν 3412, 3278, 1739, 1717, 1691, 1508, 1311, 1279, 1091 cm-1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 1.76 (3H, s), 2.15 (1H, ddd, J = 3.3, 8.3, 12.7 Hz), 2.57 (1H, ddd, J = 7.8, 9.3, 12.7 Hz), 3.42 (1H, m), 3.59 (2H, m), 3.66 (3H, s), 3.75 (2H, m), 3.90 (2H, m), 5.08 (2H, m), 7.28 (1H, m), 7.36 (2H, m), 7.44 (2H, m), 7.72 (1H, br s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 23.8, 32.9, 34.6, 39.1, 44.1, 50.7, 52.0, 61.3, 65.8, 127.3, 127.5, 128.3, 137.0, 155.3, 166.1, 170.0. MS (FAB) m/z 346 (100%, M+H+). HRMS (FAB) m/z 346.1764, C18H24N3O4 requires 346.1767.

(3S,7S)-7-Benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-methoxycarbonyl-3,7-dimethyl-1,5-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]non-5-ene 42

The amidine 41 (1:1 mixture of diastereomers) (1.0 g, 2.9 mmol) was dissolved in dry THF and the solution was cooled to −78 °C. Lithium hexamethyldisilazide (1.0M in THF, 10.2 mL) was added slowly, and the solution was stirred for 2 h, at which time methyl iodide (1.0 g, 7.0 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 3 h at −78 °C, then was allowed to warm to ca. 0 °C and was stirred for 1 h. The solution was cooled to −78 °C and a further 2 equivalents of LHMDS was added (5.8 mL), and stirring was continued for 30 min. Methyl iodide (1 eq., 185 μL) was added and the solution was stirred at −78 °C for 3 h. The solution was then allowed to warm to ambient temperature overnight. Methanol (ca. 50 mL) was added to quench the reaction and the solution was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by chromatography on silica, eluting with CH2Cl2/MeOH/isopropylamine (80:20:1) to give the product 42 (487 mg, 47%) as a colorless oil. IR ν 3395, 3293, 1738, 1717, 1690, 1538, 1375, 1261, 1219, 1090 cn−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.27 (3H, s), 1.65 (3H, s), 2.08 (1H, m), 2.62 (1H, m), 3.11 (1H, d, J = 13 Hz), 3.29 (1H, d, J = 13 Hz), 3.58–3.87 (4H, m), 3.64 (3H, s), 5.05 (2H, m), 7.28 (5H, m), 7.35 (1H, br s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 20.7, 24.3, 30.8, 32.9, 38.9, 46.6, 50.3, 52.8, 60.4, 66.1, 127.1, 127.6, 128.3, 136.5, 156.0, 166.2, 172.9. MS (FAB) m/z 360 (100%, M+H+). HRMS (FAB) m/z 360.1915, C19H26N3O4 requires 360.1923.

(3S,7S)-7-Benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-carboxy-3,7-dimethyl-1,5-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]non-5-ene 43

The amidine ester 42 (300 mg, 0.84 mmol) was dissolved in 1:1:1 THF:MeOH:1.0M LiOHaq (5 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature 18 h, and lyophilized to give a white foam. The residue was taken up in methanol (5 mL) and 3N HCl (ca. 0.3 mL) was added to lower the pH to 6. The mixture was filtered and the filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure to give the acid 43 (288 mg, 100%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOH-d4) δ 1.20 (3H, s), 1.56 (3H, s), 2.17 (1H, m), 2.58 (1H, m), 3.24 (2H, m), 3.53 (1H, m), 3.75 (3H, s), 5.09 (2H, s), 7.36 (5H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, MeOH-d4) δ 20.1, 22.5, 32.7, 39.1, 46.0, 50.1, 50.9, 60.7, 66.4, 127.5, 127.7, 128.1, 155.6, 165.4, 177.2. MS (FAB) m/z 368 (8%, M+Na+), 352 (38, M+Li+), 346 (44, M+H+), 313 (100). HRMS (FAB) m/z 346.1773, C18H24N3O4 requires 346.1767.

(3S,7S)-7-Benzyloxycarbonylamino-3-tert-butoxycarbonylamino-3,7-dimethyl-1,5-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]non-5-ene Diphenylphosphate 44

To a solution of the acid 43 (100 mg, 0.29 mmol) in dry t-butanol/acetonitrile (2:1, 4.5 mL) in a screw-capped pressure bottle was added DPPA (112 mg, 0.41 mmol) and triethylamine (32 mg, 0.32 mmol). The bottle was flushed with argon before affixing the cap, then was placed in a sand bath at ca. 110°. The solution was heated for 36 h, then was allowed to cool. Ether (8 mL) was added and the solution was stored at 4° overnight. The precipitate (diphenyl phosphate) was removed by filtration, the solid was washed with ether, and the filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by chromotography on silica to give the amidine diphenyl phosphate salt 44 (84 mg, 45%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOH-d4) δ 1.41 (3H, s), 1.43 (9H, s), 1.52 (3H, s), 2.15 (1H, ddd, J = 3.5, 7.0, 12.7 Hz), 2.59 (1H, m), 3.16 (1H, d, J = 13 Hz), 3.35 (1H, d, J = 13 Hz), 3.73 (2H, m), 3.79 (1H, d, J = 13 Hz), 3.89 (1H, d, J = 13 Hz), 5.07 (1H, d, J = 12.4 Hz), 5.14 (1H, d, J = 12.4 Hz), 7.34 (5H, m); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 21.3, 24.6, 28.2, 31.7, 33.3, 45.8, 51.2, 53.8, 60.8, 66.6, 79.7, 120.3*, 120.3*, 122.9*, 127.7, 128.3, 129.0, 136.4, 153.1*, 155.0, 156.2, 166.7, [* = (PhO)2PO2−]; MS (FAB) m/z 417 (100%, M+H+). HRMS (FAB) m/z 417.2512, C22H33N4O4 requires 417.2502.

Supplementary Material

Experimental methods and spectroscopic data for compounds 16, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28 and 34; spectroscopic data for compounds 31 and 39; 1H spectra for compounds 17, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26–30, 32, 35–38 and 40–44 (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (USA) grant GM-28965.

References

- 1.Freidinger RM. J Med Chem. 2003;46:5553–5566. doi: 10.1021/jm030484k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cluzeau J, Lubell WD. Biopolymers (Pept Sci) 2005;80:98–150. doi: 10.1002/bip.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souers AJ, Ellman JA. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:7431–7448. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanessian S, McNaughton-Smith G, Lombart HG, Lubell WD. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:12789–12854. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eguchi M, Kahn M. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2002;2:447–462. doi: 10.2174/1389557023405783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.d l Figuera N, Martin-Martinez M, Herranz R, Garcia-Lopez MT, Latorre M, Cenarruzabeitia E, d Rio J, Gonzalez-Muniz R. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00677-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W, Xiong C, Hruby VJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:3159–3161. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HO, Nakanishi H, Lee MS, Kahn M. Org Lett. 2000;2:301–302. doi: 10.1021/ol990355r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virgilio AA, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:11580–11581. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Virgilio AA, Schurer SC, Ellman JA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:6961–6964. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinds MG, Richards NGJ, Robinson JA. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1988:1447–1449. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golebiowski A, Jozwik J, Klopfenstein SR, Colson AO, Grieb AL, Russell AF, Rastogi VL, Diven CF, Portlock DE, Chen JJ. J Comb Chem. 2002;4:584–590. doi: 10.1021/cc020029u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golebiowski A, Klopfenstein SR, Chen JJ, Shao X. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:4841–4844. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Xiong C, Ying J, Wang W, Hruby VJ. Org Lett. 2003;5:3115–3118. doi: 10.1021/ol0351347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eguchi M, Lee MS, Nakanishi H, Stasiak M, Lovell S, Kahn M. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:12204–12205. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez-Rodriguez M, Garcia-Lopez MT, Herranz R. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:5177–5183. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blomberg D, Hedenstrom M, Kreye P, Sethson I, Brickmann K, Kihlberg J. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3500–3508. doi: 10.1021/jo0356863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brickmann K, Yuan Z, Sethson I, Somfai P, Kihlberg J. Chem Eur J. 1999;5:2241–2253. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baeza JL, Gerona-Navarro G, d Vega JP, Garcia-Lopez T, Gonzalez-Muniz R, Martin-Martinez M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:3689–3693. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrero S, Garcia-Lopez MT, Latorre M, Cenarruzabeitia E, Rio JD, Herranz R. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3866–3873. doi: 10.1021/jo0256336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond MC, Bartlett PA. J Org Chem. 2007;72:3104–3107. doi: 10.1021/jo062664i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips ST, Blasdel LK, Bartlett PA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4193–4198. doi: 10.1021/ja045122w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boatman PD, Ogbu CO, Eguchi M, Kim HO, Nakanishi H, Cao B, Shea JP, Kahn M. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1367–1375. doi: 10.1021/jm980354p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandrasekhar S, Babu BN, Prabhakar A, Sudhakar A, Reddy MS, Kiran MU, Jagadeesh B. Chem Commun. 2006:1548–1550. doi: 10.1039/b518420g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loughlin WA, Tyndall JDA, Glenn MP, Fairlie DP. Chem Rev. 2004;104:6085–6117. doi: 10.1021/cr040648k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reid RC, Pattenden LK, Tyndall JDA, Martin JL, Walsh T, Fairlie DP. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1641–1651. doi: 10.1021/jm030337m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin RE, Maplestone RA, Sefler AM, Liu K, Hruzewicz WN, Liu CW, Cho HS, Wemmer DE, Bartlett PA. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6461–6472. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kemp DS, Allen TJ, Oslick SL, Boyd JG. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:4240–4248. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maison W, Arce E, Renold P, Kennedy RJ, Kemp DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10245–10254. doi: 10.1021/ja010812a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis JM, Tsou LK, Hamilton AD. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:326–334. doi: 10.1039/b608043j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horwell DC, Howson W, Ratcliffe GS, Willems HMG. Bioorg Med Chem. 1996;4:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(95)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagai U, Sato K, Nakamura R, Kato R. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:3577–3592. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ternansky RJ, Draheim SE. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:777–796. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bock MG, DiPardo RM, Evans BE, Rittle KE, Freidinger RM, Chang RSL, Lottit VJ. J Med Chem. 1988;31:268–271. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oediger H, Moller F, Eiter K. Synthesis. 1972;11:591–598. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shrader WD, Marlowe CK. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1995;5:2207–2210. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karady S, Amato JS, Weinstock LM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:4337–4340. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheibye S, Pedersen BS, Lawesson SO. Bull Soc Chim Belg. 1978;87:229–238. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foloppe MB, Rault S, Robba* M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:2803–2804. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunstan S, Henbest HB. J Chem Soc. 1957:4905–4908. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker SR, Parsons AF, Wilson M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:331–332. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laurent M, Ceresiat M, Marchand-Brynaert J. Eur J Org Chem. 2006:3755–3766. doi: 10.1021/jo030377y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carpino LA, Padykula RE, Barr DE, Hall FH, Krause JG, Dufresne RF, Thoman CJ. J Org Chem. 1988;53:2565–2572. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christoforou IC, Koutentis PA. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:3681–3693. doi: 10.1039/b607442a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rebek J, Jr, Askew B, Killoran M, Nemeth D, Lin FT. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2426–2431. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sibi MP, Patil K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:1235–1238. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental methods and spectroscopic data for compounds 16, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28 and 34; spectroscopic data for compounds 31 and 39; 1H spectra for compounds 17, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26–30, 32, 35–38 and 40–44 (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.