Water limitation affects all types of organisms at some stage during their life cycle; therefore, many strategies have been selected through evolution to cope with water deficit, including changes in enzyme activities and in gene expression, among others. In plants, a group of very hydrophilic proteins, known as LATE EMBRYOGENESIS ABUNDANT (LEA) proteins, accumulate to high levels during the last stage of seed maturation (when acquisition of desiccation tolerance occurs in the embryo) and during water deficit in vegetative organs, suggesting a protective role during water limitation (Dure, 1993b; Bray, 1997; Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000; Hoekstra et al., 2001).

LEA proteins have been grouped into various families on the basis of sequence similarity (see below; Dure et al., 1989; Ingram and Bartels, 1996; Colmenero-Flores et al., 1999; Cuming, 1999). Although significant similarity has not been detected between the members of the different families, a unifying and outstanding feature of most of them is their high hydrophilicity and high content of Gly and small amino acids like Ala and Ser (Baker et al., 1988; Dure, 1993b).

Most LEA proteins are part of a more widespread group of proteins called “hydrophilins.” The physicochemical characteristics that define this set of proteins are a Gly content greater than 6% and a hydrophilicity index greater than 1. By database searching, it was shown that this criterion selects most LEA proteins, as well as additional proteins from different taxa (Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000). The genomes of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae contain five and 12 genes, respectively, encoding proteins with the characteristics of hydrophilins. The fact that the transcripts of all these genes accumulate in response to osmotic stress suggests that hydrophilins represent a widespread adaptation to water deficit (Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000; Posas et al., 2000; Yale and Bohnert, 2001; Saccharomyces Genome Database project, http://www.yeastgenome.org). Remarkably, now it is known that these proteins are distributed across archeal, eubacterial, and eukaryotic domains, as will be described later in this review.

Although the functional role of hydrophilins remains speculative, there is evidence supporting their participation in acclimation and/or in the adaptive response to stress. Ectopic expression of some plant hydrophilins (LEA proteins) in plants and yeast confers tolerance to water-deficit conditions (Imai et al., 1996; Xu et al., 1996; Swire-Clark and Marcotte, 1999; Zhang et al., 2000), and their presence has been associated with chilling tolerance (Danyluk et al., 1994, 1998; Ismail et al., 1999a, 1999b; Puhakainen et al., 2004a; Nakayama et al., 2007). An osmosensitive phenotype is caused by the deletion of the RMF hydrophilin gene in E. coli (Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000) and by the absence of a LEA protein in the moss Physcomitrella patens (Saavedra et al., 2006).

To gain further insight into their function, in vitro assays have been established similar to those used to test the role of other protective molecules such as chaperones. Examples of these are cryoprotection assays, in which the protective role of LEA proteins is tested using freeze-labile enzymes (Lin and Thomashow, 1992). Dehydration assays, in which the activities of malate dehydrogenase and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were measured in the presence or absence of a putative protecting protein, showed that hydrophilins from plants, bacteria, and yeast were able to protect their enzymatic activity. Under similar conditions, trehalose was required in a 105-fold molar excess over hydrophilins to confer the same protective level to LDH, suggesting that they confer protection via different mechanisms (Reyes et al., 2005). While hydrophilin research in different organisms has provided us with significant advances to understand their biological properties, we are still far from a complete understanding of their biological functions and activities.

Here, we review the structural and functional characteristics of hydrophilins to provide a reference platform to understand their role during the adaptive response to water deficit in plants and other organisms and to generate new ideas to elucidate their function.

LEA PROTEINS

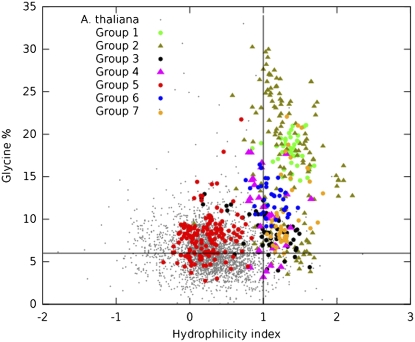

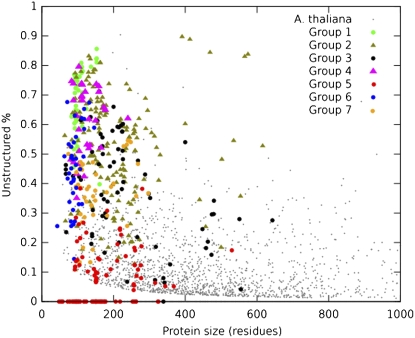

Twenty-seven years ago, Leon Dure III identified several families of proteins that accumulated to high levels during the maturation phase of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) embryogenesis (Dure and Chlan, 1981; Dure and Galau, 1981; Dure et al., 1981), which gave rise to their name as LEA proteins. The characterization of different representative cDNAs from many of these protein families uncovered their common structural features, some of which were first noticed by Dure and his colleagues. These include a high hydrophilicity, a lack or low proportion of Cys and Trp residues, and a preponderance of certain amino acid residues such as Gly, Ala, Glu, Lys/Arg, and Thr, which later led them to be considered as a subset of hydrophilins (Dure, 1993b; Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000; Fig. 1). The common structural elements among the members of different families indicate that most exist principally as randomly coiled proteins in solution. While structure modeling and structure prediction programs suggest that at least some LEA proteins from particular families contain defined conformations (Dure et al., 1989; Dure, 1993a; Close, 1996), all hydrophilic LEA proteins studied experimentally have revealed a high degree of unordered structure in solution. This has led them to be considered as intrinsically unstructured proteins (Fig. 2; McCubbin et al., 1985; Eom et al., 1996; Lisse et al., 1996; Russouw et al., 1997; Ismail et al., 1999b; Wolkers et al., 2001; Soulages et al., 2002, 2003; Goyal et al., 2003; Shih et al., 2004; Dyson and Wright, 2005; Tompa, 2005; Mouillon et al., 2006; Kovacs et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of LEA proteins according to the properties that define the hydrophilins. This analysis includes data for all LEA proteins considered in this work (378). All points on the top right quadrant correspond to proteins that can be considered as hydrophilins according to their definition (hydrophilicity index > 1, Gly > 6%). Also, 3,000 randomly chosen Arabidopsis proteins are shown as reference. To obtain the hydrophilicity index, the average hydrophobicity of all amino acids in the protein was multiplied by −1 (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982).

Figure 2.

Protein size and fraction predicted as unstructured of LEA proteins belonging to different groups. Also, 3,000 randomly chosen Arabidopsis proteins are shown as reference. Many of them (1,350 of 3,000) cannot be seen because they overlap the x axis, as they were predicted to be 0% unstructured. The unstructured fraction was calculated according to Dosztányi et al. (2005), using a sliding window of 21 amino acids.

In plants, most of these proteins and their mRNAs accumulate to high concentrations in embryo tissues during the last stages of seed development before desiccation (Baker et al., 1988; Hughes and Galau, 1989; Ingram and Bartels, 1996; Oliveira et al., 2007; Bies-Ethève et al., 2008; Hundertmark and Hincha, 2008) and also in vegetative tissues exposed to dehydration, osmotic, and/or low-temperature stress (Dure et al., 1989; Chandler and Robertson, 1994; Robertson and Chandler, 1994; Ingram and Bartels, 1996; Bray, 1997; Campbell and Close, 1997; Thomashow, 1998; Bies-Ethève et al., 2008; Hundertmark and Hincha, 2008). These observations have suggested their involvement in the plant response to water-limiting environments, probably by playing roles in ameliorating different stress effects; however, their precise functions remain elusive.

Members of the LEA protein families appear to be ubiquitous in the plant kingdom. Their presence has been confirmed not only in angiosperms and gymnosperms (Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 1996; Bray, 1997; Cuming, 1999) but also in seedless vascular plants (e.g. Selaginella; Oliver et al., 2000; Alpert, 2005; Iturriaga et al., 2006) and even in bryophytes (e.g. Tortula, Physcomitrella; Alpert and Oliver, 2002; Oliver et al., 2004; Saavedra et al., 2006; Proctor et al., 2007), pteridophytes (e.g. ferns; Reynolds and Bewley, 1993), and algae (Honjoh et al., 1995; Tanaka et al., 2004). In addition, similar proteins are found in bacteria and yeast (Stacy and Aalen, 1998; Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000), nematodes (Solomon et al., 2000; Browne et al., 2004), archaea (F. Campos, unpublished data), and fungi (Mtwisha et al., 1998; Abba et al., 2006).

Recently, computational methods to study and/or classify these proteins have been developed (Wise, 2002; Wise and Tunnacliffe, 2004). These methods consider the similarities in peptide composition rather than the similarities in their amino acid sequences. Although this kind of analysis may emphasize those characteristics related to the amino acid composition of a protein, it neglects the importance of conserved motifs that could be essential to define their structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships.

Here, we will adopt the classification introduced by Dure's group, in which LEA proteins are categorized into at least six families by virtue of similarities in their deduced amino acid sequences (Galau and Hughes, 1987; Baker et al., 1988; Dure et al., 1989; Dure, 1993b; Colmenero-Flores et al., 1997; Cuming, 1999). This classification has been very useful because it not only allows the identification of different families, but it is also possible to distinguish motifs conserved across species, which are unique to each family. Based on these characteristics and considering all available sequence information from different plant species, we have grouped LEA proteins into seven distinctive groups or families. Groups 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 correspond to the hydrophilic or “typical” LEA proteins (Supplemental Tables S1–S6), whereas those LEA proteins that show hydrophobic characteristics (“atypical”) have been kept in group 5, where they could be subclassified according to their homology.

The nomenclature in this work will follow the terminology introduced by Cuming (1999), in which groups 1 to 4 correspond to the first LEA proteins described from cotton: group 1 (D-19), group 2 (D-11), group 3 (D-7/D-29), and group 4 (D-113). In group 5 are the atypical LEA proteins (D-34, D-73, D-95; Dure, 1993b; Cuming, 1999). Similarly, the remaining two groups are designated with the consecutive numbers and associated to the name of the proteins that were used to describe these groups for the first time: group 6 (LEA18; Colmenero-Flores et al., 1997) and group 7 (ASR1 [for ABSCISIC ACID STRESS RIPENING1]; Silhavy et al., 1995; Rossi et al., 1996). Although two recent publications report an inventory of the LEA proteins encoded in the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genome (Bies-Ethève et al., 2008; Hundertmark and Hincha, 2008), we did not follow the same nomenclature because they have included in their classification Arabidopsis LEA proteins not found in other plant species. Table I shows a comparison of the nomenclature used in this work with the corresponding PFAM number and other classifications.

Table I.

Correspondence between different nomenclatures given to LEA protein groups

*, Used by Bies-Ethève et al. (2008) to differentiate proteins initially identified as related to group 5 but revealed as belonging to group 3. –, Used to denote groups that were not identified by these authors.

| This Work | Dure | Bies-Ethève | PFAM | PFAM No. | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D-19 | 1 | LEA_5 | PF00477 | Em1, Em6 |

| 2 | D-11 | 2 | Dehydrin | PF00257 | Dehydrin, RAB |

| 3A | D-7 | 3 | LEA_4 | PF02987 | ECP63, PAP240, PM27 |

| 3B | D-29 | 3* | LEA_4 | PF02987 | D-29 |

| 4A | – | 4 | LEA_1 | PF03760 | LE25_LYCES |

| 4B | D-113 | 4 | LEA_1 | PF03760 | PAP260, PAP051 |

| 5A | D-34 | 5 | SMP | PF04927 | PAP140 |

| 5B | D-73 | 6 | LEA_3 | PF03242 | AtD121, Sag21, lea5 |

| 5C | D-95 | 7 | LEA_2 | PF03168 | LEA14 |

| 6 | – | 8 | LEA_6 | PF10714 | LEA18 |

| 7 | – | – | ABA_WDS | PF02496 | ASR |

GROUP 1 (D-19)

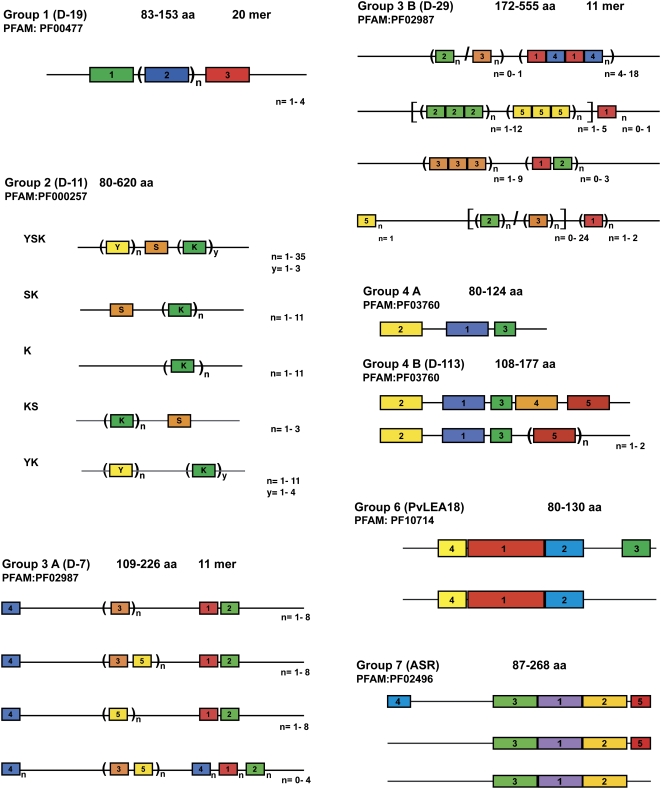

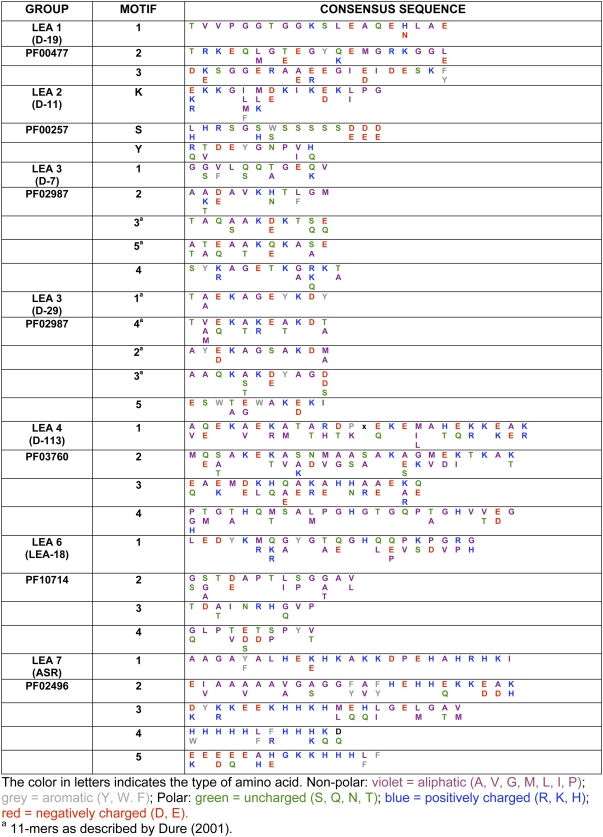

This set of LEA proteins, originally represented by the D-19 and D-132 proteins from developing cotton seeds, were recognized by an internal 20-mer sequence (Galau et al., 1992; Baker et al., 1995). They contain a very large proportion of charged residues, which contributes to their high hydrophilicity, and a high content of Gly residues (approximately 18%). This last characteristic allows us to predict that they exist largely as random coils or unstructured in aqueous solution (Eom et al., 1996; Russouw et al., 1997; Soulages et al., 2002). Structural analyses using circular dichroism (CD) strongly indicate that group 1 members exhibit a high percentage (70%–82.5% of their residues) of random coil configuration in aqueous solution, with a small percentage of the protein exhibiting a left-handed extended helical or poly-(l-Pro)-type (PII) conformation (Soulages et al., 2002). NMR analyses also indicate that this group of proteins have an unstable structure and are quite flexible (Eom et al., 1996). A comparison between group 1 proteins from all taxa reveals substantial homology, especially in the hydrophilic 20-mer motif (TRKEQ[L/M]G[T/E]EGY[Q/K]EMGRKGG[L/E]). This motif may be present in several copies arranged in tandem (from one to four in plant species, and up to eight in other organisms). In plant proteins, two other conserved motifs were identified in this work, an N-terminal motif (TVVPGGTGGKSLEAQE[H/N]LAE) located just upstream of the 20-mer and a C-terminal motif (D[K/E]SGGERA[A/E][E/R]EGI[E/D]IDESK[F/Y]; Fig. 3; Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 3.

Array of the distinctive motifs in the LEA protein groups. Each block contains a schematic representation of the arrangement of the motifs that distinguish each group of LEA proteins and their corresponding subgroups. Although similar colors and numbers indicate the different motifs for each group, they do not imply any sequence relation among the motifs in the different blocks. The amino acid sequence corresponding to each motif represented here is shown in Table II. The range of protein sizes in each group is indicated at the top of each block, in number of amino acid (aa) residues.

Noteworthy, similar proteins to group 1 LEA proteins have been found in Bacillus subtilis (Stacy and Aalen, 1998) and in other soil bacterial species. Homologous sequences have been detected in uncultured methanogenic archaeons, containing one, two, or three 20-mer repeats, and in the crustacean Artemia franciscana, in which two genes encoding group 1 LEA-like proteins containing four and eight 20-mer repeats, respectively, were found (F. Campos, unpublished data). Therefore, LEA group 1 is unique in its representation across all taxonomic domains: archaea, bacteria, and eukarya.

In plants, group 1 LEA proteins are preferentially accumulated during embryo development, especially in dry seeds, although they have also been detected in organs that undergo dehydration, such as pollen grains (Ulrich et al., 1990; Espelund et al., 1992; Wurtele et al., 1993; Hollung et al., 1994; Williams and Tsang, 1994; Prieto-Dapena et al., 1999; Vicient et al., 2001). Additionally, many of the characterized genes of this group are responsive to abscisic acid (ABA) and/or water-limiting conditions, mainly in embryos and, in a few cases, in vegetative tissues of young seedlings (Gaubier et al., 1993; Vicient et al., 2000).

Their possible role in the adaptation of different organisms to water scarcity is supported by the fact that the transcripts of bacterial group 1 LEA-like proteins also accumulate under stressful conditions, such as stationary growth phase, Glc or phosphate starvation, high osmolarity, high temperature, and hyperoxidant conditions (Stacy and Aalen, 1998). Further evidence comes from the presence of these proteins in organisms with extreme habitats, such as archaeons (uncultured like methanogenic RC1), as well as in some primordial saltwater crustaceans such as Artemia (Wang et al., 2007). Group 1 LEA-like proteins are particularly abundant in the thick-shelled eggs of Artemia, whose encysted form can survive in a dried, metabolically inactive state for 10 or more years while retaining the ability to endure severe environmental conditions (Macrae, 2005).

Direct evidence showing a function for group 1 LEA proteins is scarce. In vitro experiments using recombinant versions of wheat (Triticum aestivum) Em protein suggested their ability to protect citrate synthase or LDH from aggregation and/or inactivation due to desiccation or freezing (Goyal et al., 2005; Gilles et al., 2007). A mutation in one the predicted α-helical domains in the N terminus of the rEm protein suggested a role for this region in providing protection from drying (Gilles et al., 2007). Tolerance to stress conditions induced by the constitutive expression of genes from this group has not been reported in plants; however, the expression of wheat TaEm in S. cerevisiae seems to attenuate the growth inhibition of yeast cultures normally observed in high-osmolarity media (Swire-Clark and Marcotte, 1999). Also, the absence of one of two group 1 members in Arabidopsis plants led to a subtle phenotype of premature seed dehydration and maturation, suggesting a role during seed development (Manfre et al., 2006). The expression in vegetative tissues from plants grown under optimal growth conditions of some of the group 1 LEA proteins implies that they may also have a role during normal seed/seedling development.

GROUP 2 (D-11)

This group of LEA proteins, also known as “dehydrins,” was originally identified as the “D-11” family in developing cotton embryos. Group 2 LEA proteins are the most characterized group of LEA proteins. Typically, they are highly hydrophilic, contain a high proportion of charged and polar amino acids and a low fraction of nonpolar, hydrophobic residues, and lack Trp and frequently Cys residues; hence, they can also be considered as hydrophilins (Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000). A distinctive feature of group 2 LEA proteins is a conserved, Lys-rich 15-residue motif, EKKGIMDKIKEKLPG, named the K-segment (Close et al., 1989, 1993), which can be found in one to 11 copies within a single polypeptide (Fig. 3; Table II). An additional motif also found in this group is the Y-segment, whose conserved consensus sequence is [V/T]D[E/Q]YGNP, usually found in one to 35 tandem copies in the N terminus of the protein (Fig. 3; Table II; Close et al., 1993; Close, 1996; Campbell and Close, 1997). Many proteins of this group also contain a tract of Ser residues, called the S-segment, which in some proteins can be phosphorylated (Fig. 3; Table II; Vilardell et al., 1990; Plana et al., 1991; Goday et al., 1994; Jiang and Wang, 2004). Less conserved motifs (Φ-segments), which are usually rich in polar amino acids and lay interspersed between K-segments, are present in some proteins of this group (Campbell and Close, 1997). The presence and arrangement of these different motifs in a single polypeptide allow the classification of group 2 LEA proteins into five subgroups (Campbell and Close, 1997). Proteins that only contain the K-segment are in the K-subgroup, and those that include the S-segment followed by K-segment are in the SK-subgroup. In addition, there are the YSK-, YK-, and KS-subgroups (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table S2; Campbell and Close, 1997). Proteins with these structural characteristics have been detected in different organisms of the Plantae kingdom, in nonvascular plants, like the moss P. patens (Saavedra et al., 2006), in seedless vascular plants such as the lycopod Selaginella lepidophylla (Iturriaga et al., 2006), and, more commonly, in all seed plants investigated (Supplemental Table S2).

Table II.

Consensus amino acid sequences of the different motifs characteristic of each LEA protein group

Experimental structural analysis of four group 2 LEA proteins, Dsp16 (YSK2) from resurrection plant (Craterostigma plantagineum; Lisse et al., 1996), 35-kD protein (Y2K) from cowpea (Vigna unguiculata; Ismail et al., 1999b), rGmDHN1 (Y2K) from soybean (Glycine max; Soulages et al., 2003), and ERD10 (SK3) from mouse-ear cress (Arabidopsis; Bokor et al., 2005), indicated that these proteins are in a largely hydrated and unstructured conformation in aqueous solution. However, equilibrium between two extended conformational states, unordered and PII structures, were also detected in the case of GmDHN1, with a low degree of transitional cooperativity. CD spectra of full-length Arabidopsis dehydrins (COR47, LTI29, LTI30, RAB18) and isolated peptides (K-, Y- and K-rich segments) showed mostly unordered structures in solution, with a variable content of poly-Pro helices. However, neither temperature, metal ions, nor stabilizing salts could promote ordered structures in either the peptides or the full-length proteins (Mouillon et al., 2006).

The K-segment motifs of group 2 LEA proteins are predicted to form amphipathic α-helical structures and are thought to protect membranes (Dure, 1993b; Close, 1996). Accordingly, dehydrins from cowpea and the resurrection plant showed an estimated α-helical content of approximately 15%; however, this was not the case for GmDHN1, a soybean LEA protein that, although containing K-segment motifs, does not contain α-helical regions. The limited ability of this protein to adopt α-helical conformation was confirmed by CD spectroscopy in the presence of trifluoroethanol (TFE), a helix-promoting cosolvent. Even with the addition of high concentrations (up to 60% [v/v]) of TFE or SDS (1%–4%), only a small fraction of protein was able to form α-helices. Additionally, CD spectra of the protein in the presence of liposomes showed it had a very low intrinsic ability to interact with phospholipids (Soulages et al., 2003). However, it is still possible that under certain conditions promoted by dehydration, such as high ionic content or high solute concentration, the GmDHN1 protein could assume a higher proportion of ordered structure, which may play a physiological role in the plant response to water deficit.

Like group 1 LEA proteins, several studies of specific group 2 LEA proteins have confirmed that they accumulate during seed desiccation and in response to water deficit induced by drought, low temperature, or salinity (Ismail et al., 1999a; Nylander et al., 2001). These proteins are also present in nearly all vegetative tissues during optimal growth conditions (Rorat et al., 2004). A role in bud dormancy has also been attributed to group 2 LEA proteins (Muthalif and Rowland, 1994; Levi et al., 1999; Karlson et al., 2003a, 2003b). The ability to withstand freezing is highly developed in some trees, in which the buds, which are critical for reassuming growth after winter, can build up tolerance to temperatures as low as −196°C (Guy et al., 1986). Therefore, of particular interest is the fact that LEA proteins from this group are expressed in birch (Betula spp.) apices during wintertime dehydration, a period in which buds become highly desiccated during endodormancy (Rinne et al., 1998, 1999; Puhakainen et al., 2004b). Similarly, the accumulation of chilling-responsive LEA proteins from this group was detected in floral buds of blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus), a woody perennial (Muthalif and Rowland, 1994; Arora et al., 1997).

The data in the literature, obtained from different species, indicated that different types of group 2 LEA proteins can localize to common tissues (in root tips, root vascular system, stems, leaves, and flowers) during development under optimal growth conditions, while other proteins of this group seem to accumulate in specific cell types (e.g. root meristematic cells, plasmodesmata, pollen sacs, or guard cells; Nylander et al., 2001; Karlson et al., 2003a). Most of these proteins accumulate in all tissues upon water deficit imposed by drought, low temperature, or salinity, although there are those that preferentially respond to particular stress conditions: some dehydrins are strongly accumulated in response to low-temperature treatments but not to drought or salinity (Rorat et al., 2006). Other group 2 members are detected under normal growth conditions but not in response to low temperatures, while a small number of dehydrins show an unusual constitutive expression (Gilmour et al., 1992; Houde et al., 1992; Danyluk et al., 1994; Rorat et al., 2004; Sánchez-Ballesta et al., 2004). Because of the observed accumulation upon cold stress, some of the proteins in this group and some proteins in group 3 were originally designated as COR (for COLD RESPONSIVE) proteins (Lin et al., 1990; Gilmour et al., 1992; Guo et al., 1992). However, as limited information is available for proteins of the different subgroups, it is not possible to assign confidently specific accumulation patterns to particular groups or subgroups of these proteins. A similar situation is found when studying their regulation by ABA. Consistent with the fact that the ABA-responsive element was first described for a group 2 LEA gene from rice (Oryza sativa; Mundy and Chua, 1988), there are genes for this group of proteins whose expression during seed development or in response to stress is mediated by ABA (Nylander et al., 2001). However, some others are not responsive to ABA or are regulated by ABA during development but not in response to stress (Stanca et al., 1996; Giordani et al., 1999). Moreover, there are examples of dual regulation; that is, their response to stress is mediated by more than one pathway, one of which may be ABA dependent (Welling et al., 2004).

Effort has been made to determine the subcellular localization for some of these proteins. The majority of group 2 LEA proteins accumulate in the cytoplasm, and some of them are also localized to the nucleus. For nucleus-directed SK2 proteins, the phosphorylated S-segment and the RRKK sequence have been postulated as nuclear localization signals (Plana et al., 1991). However, for some proteins of this group, nuclear localization seems to be independent of the phosphorylation state of the S-segment, and even more, proteins lacking the S-segment or RRKK motif have been localized to the nucleus (Riera et al., 2004). Such complexity suggests that the transport of different types of dehydrins to the nucleus occurs via different nuclear localization pathways.

Some dehydrins are also found in other cell compartments, including the vicinity of the plasma membrane, mitochondria, vacuole, and endoplasmic reticulum (Houde et al., 1995; Egerton-Warburton et al., 1997; Danyluk et al., 1998; Borovskii et al., 2000, 2002; Heyen et al., 2002). Hence, the subcellular localization attributed to a particular protein of this group does not seem to be a general characteristic for the different group 2 LEA proteins, and care should be taken in considering membranes as a common location for these proteins.

For some proteins of this group, an ion-binding activity has been demonstrated. Various dehydrins from Arabidopsis can be efficiently purified by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography; in particular, they bind Cu2+ and Ni2+ ions (Svensson et al., 2000). Since no metal-binding motif is found in group 2 LEA proteins, this ability seems to be due to their high content of His residues, some of which are disposed as His-His pairs with a strong metal-binding affinity. For example, a citrus (Citrus unshiu) dehydrin binds Cu2+, Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+ through a specific sequence (HKGEHHSGDHH) rich in His residues (Hara et al., 2005). Moreover, acidic dehydrins such as a vacuole-associated dehydrin from celery (Apium graveolens; VCaB45) and Arabidopsis ERD14 possess calcium-binding properties, which seem to be positively modulated by phosphorylation (Heyen et al., 2002; Alsheikh et al., 2003, 2005). These findings suggest ion binding as one of the major biochemical functions of the acidic dehydrins, acting as calcium buffers or as calcium-dependent chaperone-like molecules (Alsheikh et al., 2003). Alternatively, metal binding may be related to a detoxification function needed under stress conditions, where metal toxicity is associated with the production of reactive oxygen species, commonly generated in plants exposed to water limitation (Hara et al., 2004). Thus, these proteins could act as scavengers of radicals under oxidative stress. The modulation of changes in dehydrin conformation leading to the recognition of a particular set of targets by ion binding should also be considered.

Most of the attempts to elucidate the function of these proteins have been focused on the in vitro characterization of their biochemical properties. Several proteins of this group show cryoprotective activity, which is enhanced in the presence of compatible solutes (Bravo et al., 2003; Reyes et al., 2005). Also, there is evidence indicating that dehydrins from Arabidopsis, Craterostigma, and Citrus (Hara et al., 2001; Reyes et al., 2005) prevent the inactivation of enzymes induced by partial dehydration in vitro. It is predicted that the K-segments may form amphipathic α-helices similar in structure to the lipid-binding class A2 amphipathic α-helical region found in apolipoproteins and α-synucleins associated with membranes (Segrest et al., 1992; Davidson et al., 1998). This observation raised the hypothesis that one of the roles of the group 2 LEA proteins may be related to an interaction with hydrophobic surfaces present in membranes and/or partially denatured proteins. While maize (Zea mays) DHN1 dehydrin is able to bind in vitro to lipid vesicles containing acidic phospholipids, there is no direct evidence for membrane binding through lipid-protein interactions in solution, nor for such a function in planta (Koag et al., 2003). Moreover, the prevalence of extended PII helical and unordered conformations in dehydrins is consistent with a role in providing or maintaining enough water molecules in the cellular microenvironment to preserve the functionality or stability of macromolecules or cellular structures during water scarcity conditions.

In most cases, the contribution of dehydrins to stress tolerance has been limited to the phenotypical analysis in plants and yeast, in which some of these proteins were overexpressed. For instance, overexpression of multiple Arabidopsis group 2 LEA proteins, ERD10, RAB18, COR47, and LTI30, resulted in plants with increased freezing tolerance and improved survival under low-temperature conditions (Puhakainen et al., 2004a). Also, ectopic expression of wheat DHN-5 in Arabidopsis plants improved their tolerance to high salinity and water deprivation (Brini et al., 2007). A role in stress tolerance for dehydrins is also supported by the cosegregation of a dehydrin gene with chilling tolerance during seedling emergence in cowpea (Ismail et al., 1999a). More recently, the mutation of a dehydrin gene from the moss P. patens resulted in a plant severely impaired in its capacity to resume growth after salt and osmotic stress, strongly suggesting its contribution to stress tolerance (Saavedra et al., 2006).

GROUP 3 (D-7/D-29)

Group 3 LEA proteins are characterized by a repeating motif of 11 amino acids (Dure, 1993a). Differences found in the molecular mass in this group of proteins are usually a consequence of the number of repetitions of this 11-mer motif. Additionally, we have found other conserved regions (motifs 1, 2, and 4 in subgroup D-7, and motif 5 in subgroup D-29; Table II), which may or not be repeated and whose sequences are completely different from the 11-mer (Table II). In comparison with other groups of LEA proteins, the group 3 members are quite diverse. This diversity is a consequence of changes introduced in the repeating 11-mer amino acid motif, first noticed by Dure (1993a), as well as of changes in the sequences of the other motifs. A more detailed analysis of numerous proteins (65) from different plant species confirmed the consensus sequence for the 11-mer proposed by Dure (1993a; Supplemental Table S3), as follows: hydrophobic residues (F) in positions 1, 2, 5, and 9; negative or amide residues (E, D, Q) in positions 3, 7, and 11; positive residues (K) in positions 6 and 8; and a random assortment (X) in positions 4 and 10 (FF[E/Q]XFK[E/Q]KFX[E/D/Q]). Hence, in support of the suggestion by Dure (2001), the variability in the 11-mer motif leads to a subclassification of the group 3 LEA proteins into two subgroups: 3A, represented by the cotton D-7 LEA protein; and 3B, represented by the cotton D-29 LEA protein (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table S3). The first subgroup is highly conserved; two of the motifs characteristic of these proteins (motifs 3 and 5) correspond to almost the same 11-mer described originally for this subgroup, with some variation at positions 9 and 10 (TAQ[A/S]AK[D/E]KT[S/Q]E; Table II). At the N-terminal portion of 3A proteins, we found motif 4 (SYKAGETKGRKT), and at the C-terminal portion, we found motifs 1 and 2 (GGVLQQTGEQV and AADAVKHTLGM; Table II). The other subgroup (3B) is more heterogeneous; four variations of the 11-mer were found (motifs 1–4), but the variability was restricted to the consensus sequence described above. Yet, motif 5 is highly conserved and is unique to this subgroup (Table II).

In silico predictions of the secondary structure of some group 3 proteins suggest that the 11-mer exists principally as amphipathic α-helices, which may dimerize in an unusual right-handed coiled-coil arrangement, with a periodicity defined by the 11-mer motif (Dure, 1993a). This hypothetical structure was later found in a surface layer tetrabrachion protein from Staphylothermus marinus (Peters et al., 1996; Stetefeld et al., 2000). CD analysis and IR spectroscopy of various group 3 LEA proteins indicated that they are mostly devoid of secondary structure, being largely in a random coil conformation in solution. However, in the presence of Suc, glycerol, ethylene glycol, or methanol, or after fast drying, they adopt an α-helical conformation (Dure, 2001; Wolkers et al., 2001; Goyal et al., 2003; Tolleter et al., 2007). The presence of TFE or SDS also promotes helical folding of these proteins. A slow-drying treatment led to the formation of α-helical and intermolecular extended β-sheet structures; thus, the structures of these proteins in the final dry state might depend on the drying rate (Wolkers et al., 2001). The fact that rehydration of the dried protein samples leads to the reformation of random coil structures indicates that these structural transitions are fully reversible (Tolleter et al., 2007). Soluble nonreducing sugars seem to contribute to the formation of a cytoplasmic “glass” at low water content in both mature seeds and pollen cells, which could stabilize cellular structures during this severe desiccation (Wolkers et al., 2001). As plants coaccumulate sugars and LEA proteins at the onset of desiccation, it is possible that sugars could be affecting the molecular structure of LEA proteins in the sugar glass. When D-7, a group 3 LEA protein from pollen, is dried in the presence of Suc, the protein adopts an α-helical conformation irrespective of drying rate (Wolkers et al., 2001). Structural modeling suggested that in the α-helical conformation, these proteins may form an amphipathic structure, which closely resembles that of the class A amphipathic helices involved in the membrane association found in different plasma apolipoproteins (Woods et al., 2007). This structural similarity may imply that some of the group 3 LEA proteins interact with membranes during dehydration. In support of this hypothesis, a pea (Pisum sativum) mitochondrial group 3 LEA protein (PsLEAm) was found to interact with and protect liposomes subjected to drying (Tolleter et al., 2007).

The group 3 LEA proteins are widely distributed in the plant kingdom. Their transcripts have been detected in algae (Joh et al., 1995), in nonvascular plants (Hellwege et al., 1996), in seedless vascular plants (Salmi et al., 2005), and in all seed plants in which they have been looked for.

Interestingly, proteins similar to plant group 3 LEA proteins accumulate in several nonplant organisms in response to dehydration. Examples of these are proteins from the prokaryotes Deinococcus radiodurans (Battista et al., 2001) and Haemophilus influenzae (Dure, 2001) as well as a protein from Caenorhabditis elegans (CeLEA-1), whose expression is correlated with the survival of this nematode under conditions of desiccation, osmotic, and heat stress (Gal et al., 2004). Interestingly, anhydrobiotic organisms such as the nematodes Steinernema feltiae (Solomon et al., 2000) and Aphelencus avenae (Browne et al., 2004), as well as the bdelloid rotifer Philodina roseola (Tunnacliffe et al., 2005), the chironomid Polypedilum vanderplanki (Kikawada et al., 2006), and the eucoelomate crustacean A. franciscana (Hand et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007), also accumulate these proteins in their desiccated states. A. franciscana is the most complex metazoan in which group 3 LEA-like proteins have been detected. Outside the plant kingdom, the best characterized group 3 protein is AavLEA1 from A. avenae, which showed an unstructured conformation in solution with a high degree of hydration and low compactness; yet, upon dehydration, a remarkable but reversible increase in α-helical structure was observed (Goyal et al., 2003).

Expression analysis of plant proteins in this group, as well as information available from transcriptomic projects, shows their accumulation in mature seeds and in response to dehydration, salinity, or low temperatures (Harada et al., 1989; Cattivelli and Bartels, 1990; Hsing et al., 1995; Romo et al., 2001). Some members also respond to hypoxia (Siddiqui et al., 1998) or to high-excitation pressure imposed by high light (NDong et al., 2002). As for LEA proteins from other groups, the expression of group 3 LEA proteins appears to be regulated by ABA during specific developmental stages and/or upon stress conditions (Piatkowski et al., 1990; Curry et al., 1991; Curry and Walker-Simmons, 1993; Dehaye et al., 1997; Dong and Dunstan, 1997).

The diversity of proteins in this group could suggest variety in their intracellular localization and possibly in their targets, with specific members selected to carry out their function in particular cellular compartments. In plant embryos, these proteins are uniformly distributed in the cytosol of all cell types. Group 3 D-7 LEA protein from cotton accumulates to a concentration of about 200 μm in mature cotton embryos (Roberts et al., 1993). Studies of seeds have localized group 3 LEA proteins to the cytoplasm and protein storage vacuoles, as is the case for HVA1 from barley (Hordeum vulgare; Marttila et al., 1996), whereas PsLEAm is distributed within the mitochondrial matrix of pea seeds (Grelet et al., 2005). Group 3 proteins are also detected in vegetative tissues. WAP27A and WAP27B are abundantly accumulated in endoplasmic reticulum of cortical parenchyma cells of the mulberry tree (Morus bombycis) during winter (Ukaji et al., 2001); and WCS19 accumulates specifically in wheat leaves and rye (Secale cereale) during cold acclimation, where it was localized within the chloroplast stroma (NDong et al., 2002).

The different approaches followed to elucidate the function of group 3 proteins indicate that they also contribute to counteract the damage produced by water limitation. One of their roles in anhydrobiotic organisms might be to contribute to the formation of a tight hydrogen-bonding network in the dehydrating cytoplasm, together with sugars to promote a long-term stability of sugar glasses during anhydrobiosis. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that a dehydrated mixture of Suc and LEA protein (D-7 from pollen) shows both a higher glass transition temperature and increased average strength of hydrogen bonding than dehydrated Suc alone (Wolkers et al., 2001).

The high correlation found between the accumulation of group 3 LEA proteins or their transcripts and the onset of stress, induced by low temperatures (cold and freezing), dehydration, or salinity, prompted their consideration as essential factors of the adaptation process to this type of environmental insult. This hypothesis was strengthened by several observations of the expression of these proteins in different plant species. In wheat, roots lacking group 3 LEA proteins were unable to resume growth and died upon dehydration and subsequent rehydration, in contrast to shoot and scutellar tissues, which accumulated high levels of these proteins and survived the treatment (Ried and Walker-Simmons, 1993). In indica rice varieties, group 3 LEA protein levels were significantly higher in roots from salt-tolerant compared with salt-sensitive varieties (Moons et al., 1995). Also, the accumulation of the chloroplastic group 3 LEA-L2 protein was directly correlated with the capacity of different wheat and rye cultivars to develop freezing tolerance (NDong et al., 2002). Gain-of-function experiments in different plant species further reinforce their role in the adaptation to stress conditions. The constitutive expression of the wheat group 3 LEA-L2 protein in Arabidopsis resulted in a significant increase in the freezing tolerance of cold-acclimated plants (NDong et al., 2002). Expression of the barley HVA1 gene regulated by the ACTIN1 gene promoter, leading to high-level constitutive accumulation of the HVA1 protein in both leaves and roots of transgenic rice plants, conferred tolerance to water deficit and salt stress (Xu et al., 1996). Comparable results were obtained when the same gene was constitutively expressed in transgenic wheat, rice, creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera var. palustris), and mulberry (Sivamani et al., 2000; Chandra Babu et al., 2004; Fu et al., 2007; Lal et al., 2008). The overexpression of the soybean PM2 protein in transgenic bacteria, and of wheat TaLEA3 and barley HVA1 proteins in yeast, also resulted in the generation of salt- and freezing-tolerant organisms (Zhang et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2005).

The direct contribution of these proteins to adaptation to water-limiting environments has been addressed through loss-of-function experiments in bacteria and nematodes. Mutants lacking group 3 LEA-like proteins from D. radiodurans, a bacterium highly tolerant to ionizing radiation and desiccation, showed sensitivity to dehydration. Similarly, C. elegans containing an interrupted group 3 LEA-like gene was susceptible to desiccation (Battista et al., 2001; Gal et al., 2004).

Employing in vitro assays to explore a protective role of enzymatic activities under dehydration conditions showed that group 3 LEA proteins from Arabidopsis (AtLEA76 and COR15am; Reyes et al., 2005; Nakayama et al., 2007), pea (PsLEAm; Grelet et al., 2005), and A. avenae (AavLEA1; Goyal et al., 2005) are effective in protecting enzymes such as LDH, malate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, fumarase, and rhodanese against partial dehydration. Likewise, freeze-thaw assays in the presence of group 3 LEA proteins from the green alga Chlorella vulgaris (HIC6; Honjoh et al., 2000) and of group 3 LEA-like protein from the anhydrobiotic nematode A. avenae (AavLEA1; Goyal et al., 2005) showed that these types of LEA proteins are capable of preventing enzyme inactivation when enzymes such as LDH are used. Recent in vitro experiments suggested that the nematode group 3 LEA-like protein is able to prevent the aggregation induced by severe desiccation of water-soluble proteins from nematodes and mammalian cells (Chakrabortee et al., 2007). In addition to supporting a role as protector molecules under water limitation, these results indicate that LEA proteins may function to provide a water-rich environment to their target enzymes, preventing their inactivation by possibly maintaining protein integrity as long as water is restrictive.

GROUP 4 (D-113)

Group 4 LEA proteins are of widespread occurrence in the plant kingdom, including nonvascular plants (bryophytes) and vascular plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms). As predicted by Dure's classification, the proteins of this family are conserved in their N-terminal portion, which is about 70 to 80 residues long and is predicted to form amphipathic α-helices, while the less conserved C-terminal portion is variable in size (Dure, 1993b).

A motif that has characterized the proteins in this group is motif 1, located at the N-terminal region with the following consensus sequence: AQEKAEKMTA[R/H]DPXKEMAHERK[E/K][A/E][K/R] (Table II). However, four additional motifs can be distinguished in many group 4 LEA proteins. The presence or absence of motif 4 or 5 defines two subgroups within the family (Fig. 3). The first subgroup (group 4A) consists of small proteins (80–124 residues long) with motifs 2 and/or 3 flanking motif 1. The other subgroup (group 4B) has longer representatives (108–180 residues) that, in addition to the three motifs in the N-terminal portion, may contain motifs 4 and/or 5 at the C-terminal region (Supplemental Table S4). D-113 protein from cotton, the first discovered of this group, belongs to group 4B.

In silico analysis for group 4 LEA proteins predicts that the first 70 to 80 residues could adopt an α-helix structure, whereas the rest of the protein assumes a random coil conformation (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982). Spectroscopic analysis of a soybean group 4 LEA protein (GmPM16) partially confirmed these predictions. In aqueous solution, this protein is mainly disordered, although some helical structures were detected (Shih et al., 2004). Interestingly, in the presence of compounds able to induce ordered structures, such as 1% SDS, 50% TFE, or in the dry state, this protein adopts an almost 90% α-helix conformation. Most notably, these conformational changes are reversible. Similar to group 3 LEA proteins, the GmPM16 protein interacts with Suc and raffinose and increases the glass transition temperature of the sugar-protein matrix, which leads to the suggestion that a common role for group 3 and group 4 LEA proteins is related to the formation of tight glass matrices in dry seeds (Shih et al., 2004).

The proteins of this group were originally found highly accumulated in dry embryos. One of these, cotton D-113 protein, was found homogeneously distributed in all embryo tissues at a concentration of nearly 300 μm (Roberts et al., 1993). Later, similar proteins were found to accumulate in vegetative tissues in response to water deficit. In tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants, group 4 LEA transcripts (LE25) accumulated in leaves in response to water deficit and ABA (Cohen et al., 1991). In Arabidopsis vegetative tissues, the transcripts of the group 4 LEA proteins also accumulated in response to water-deficit treatments (Y. Olvera-Carrillo, unpublished data). As for the LEA proteins in the other groups, scarce information exists regarding the distribution of group 4 LEA proteins in different plant tissues. Soybean GmPM16 transcripts accumulated in mesophyll cells of cotyledons and in small amounts in the hypocotyl-radicle axis tissues (Shih et al., 2004). In wheat, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR from developing seeds showed high accumulation of group 4 LEA transcripts in coleorhizae, whereas in developing seeds under abiotic stress, they accumulated in coleoptiles (Ali-Benali et al., 2005). More general information can be extracted from data available from ESTs obtained from Arabidopsis cDNA libraries of dry seeds, in which all group 4 LEA members are among the most abundantly accumulated transcripts in the dry seed stage (Delseny et al., 2001). In addition, scrutiny of the publicly available EST data banks indicates that group 4 LEA homologues in many plant species accumulate under drought in shoot meristems and in developing and dry seeds.

Although genes in this group respond to ABA (Zimmermann et al., 2004), the ability of this phytohormone to control group 4 LEA protein expression during development or in response to stress conditions remains undefined. One of the few examples in which the participation of ABA in the regulation of group 4 LEA gene expression was shown is the PAP51 gene (the Arabidopsis homolog of cotton D-113), which during seed development is repressed in the lec1-1 mutant, is not affected in the abi3-4 mutant, but is up-regulated in the abi5-5 background (Delseny et al., 2001). GUS expression driven by the LEA D-113 promoter in transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) seedlings showed that this gene responds to ABA, dehydration, and high salinity in vegetative tissues and further confirms its specific expression at the late stage of seed development (Luo et al., 2008). Gene expression analysis during germination suggests that the decrease in the transcript levels for some group 4 LEA genes is partially due to their repression associated with histone deacetylation (Tai et al., 2005).

As for other LEA proteins, in vitro studies using one member of the Arabidopsis group 4 LEA protein family (D-113 homolog) showed that its presence during controlled dehydration experiments prevented the inactivation of LDH, even after 99% water loss (Reyes et al., 2005), suggesting a protective role during dehydration. This possibility is supported by a functional analysis of the Arabidopsis group 4 LEA protein family using overexpression and loss-of-function approaches, which indicate that these proteins contribute to the plant's ability to cope with water deficit (Y. Olvera-Carrillo, unpublished data). Similarly, the transient silencing of a peanut (Arachis hypogaea) group 4 LEA gene in tomato plants appeared to result in a lower tolerance to drought (Senthil-Kumar and Udayakumar, 2006).

GROUP 5 (HYDROPHOBIC OR ATYPICAL LEA PROTEINS)

To avoid further confusion, we have kept group 5 for those LEA proteins that contain a significantly higher proportion of hydrophobic residues. Because this work is focused on the hydrophilic LEA proteins, this section does not represent an extensive review of the available information on this group of proteins. All LEA proteins with a higher content of hydrophobic residues than typical LEA proteins are included in this group (Fig. 1); thus, this group incorporates nonhomologous proteins. For further classification, we suggest the designation of subgroups according to their sequence similarity. Because the first proteins described for this group were D-34, D-73, and D-95 (Baker et al., 1988; Cuming, 1999), we assigned them to subgroups 5A, 5B, and 5C, respectively (Table I). Given their physicochemical properties, these proteins are not soluble after boiling, suggesting that they adopt a globular conformation (Baker et al., 1988; Galau et al., 1993; Cuming, 1999). Further experimental data from some of the proteins in this group confirmed this prediction (Singh et al., 2005). Although little is known about this set of proteins, the available data indicate that their transcripts accumulate during the late stage of seed development and in response to stress conditions, such as drought, UV light, salinity, cold, and wounding (Kiyosue et al., 1992; Maitra and Cushman, 1994; Zegzouti et al., 1997; Stacy et al., 1999; Park et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2005).

GROUP 6 (PVLEA18)

PvLEA18 protein from bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) was the first protein described from this group (Colmenero-Flores et al., 1997). To date, 36 members of this family have been identified from different species of vascular plants (Supplemental Table S5). The proteins in this group are characterized by their small size (approximately 7–14 kD) and high conservation. Four motifs distinguish this group, two of which (motifs 1 and 2) are highly conserved (Table II). Noteworthy, the sequence LEDYK present in motif 1 and the Pro and Thr residues located in positions 6 and 7, respectively, in motif 2 show 100% conservation (Table II; Fig. 3). In general, these proteins are highly hydrophilic, lack Cys and Trp residues, and do not coagulate upon exposure to high temperature. Typically, during SDS-PAGE, they migrate at a higher molecular mass than the one predicted from their deduced amino acid sequences. Their physicochemical characteristics and in silico analyses predict that group 6 LEA proteins are intrinsically unstructured (Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000).

Expression studies in plants are exemplified by work carried out on PvLEA18. The PvLEA18 transcript and protein levels are highly accumulated in dry seeds and pollen grains and also respond to water deficit and ABA treatments. Under normal growth conditions, the expression of this gene is also regulated during development (Colmenero-Flores et al., 1999). For example, high protein and transcript accumulation was detected in the expansion zone of bean seedling hypocotyls, which show lower water potentials than those from nongrowing regions. They also accumulate in meristematic regions, such as the apical meristem and root primordia, as well as in the vascular cylinder and within epidermal tissue. The high accumulation of PvLEA18 in the embryo radicle during the early stages of germination suggested a protective role during this process. Immunolocalization experiments indicated that the PvLEA18 protein is present in the cytosol and nuclei of different cell types in vegetative tissues (Colmenero-Flores et al., 1999).

Analysis of Arabidopsis transgenic lines harboring the PvLEA18 promoter fused to the GUS reporter gene, either with the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) from PvLEA18 or with the NOS 3′ UTR, showed that the expression pattern of the chimeric gene is similar to that of the endogenous gene in bean upon water deficit and ABA treatment and during development. The PvLEA18 3′ UTR is responsible for most of the GUS activity induction under water deficit but not in response to ABA treatments (Moreno-Fonseca and Covarrubias, 2001). Further analysis indicates that the PvLEA18 3′ UTR participates in the regulation of PvLEA18 protein expression at the translational level, allowing for preferential polysome loading of the GUS reporter transcript under water deficit (M. Battaglia and A.A. Covarrubias, unpublished data). These results suggest that this region and some mRNA binding proteins are important for a selective translational enhancement of the PvLEA18 mRNA to enable an efficient response to this stress condition.

While there is no direct information regarding the possible function of the proteins in this group, results obtained from in vitro dehydration assays indicated that PvLEA18, in contrast to LEA proteins from other groups (2, 3, and 4), was unable to prevent dehydration inactivation of reporter enzymes (Reyes et al., 2005). This result suggests that the molecular targets of these proteins are different from those of other LEA proteins, and it indicates that their hydrophilicity is not the only characteristic relevant for their protective function under water-limiting environments.

GROUP 7 (ASR1)

The ASR proteins, considered to be members of the hydrophilins, are small, heat stable, and intrinsically unstructured (Silhavy et al., 1995; Frankel et al., 2006; Goldgur et al., 2007). They not only share physiochemical properties with other LEA proteins, but like all proteins of this type, they accumulate in seeds during late embryogenesis and in response to water-limiting conditions (Maskin et al., 2008). Several ASR genes have been identified from various species of dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants (Silhavy et al., 1995; Rossi et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1998; Vaidyanathan et al., 1999) as well as from gymnosperm species like Pinus taeda (Padmanabhan et al., 1997) and Ginkgo biloba (Shen et al., 2005; Supplemental Table S6). However, no ASR-like genes are found in Arabidopsis. All known ASR proteins contain three highly conserved regions (motifs 1, 2, and 3; Fig. 3). One of these motifs (motif 3) is located within the C-terminal region and contains a putative nuclear localization signal (Silhavy et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2003, 2005). The other three motifs (1, 2, and 5) contain stretches of His residues. Motif 5 has only been found in the N terminus of the ASR1 protein (Fig. 3). The sequence-specific Zn2+-dependent DNA-binding activity shown for motif 5 suggests that the His-rich regions in this motif and in motifs 1 and 2 may contribute to this activity (Kalifa et al., 2004a; Goldgur et al., 2007). An additional conserved region (motif 4) has been detected at the C terminus of many proteins in this group, and like motifs 1, 2, and 5, it shows long His stretches (eight to 12; Table II; Fig. 3). Subcellular fractionation experiments using tomato fruit chromatin fractions indicated that tomato ASR1 is located within the nucleus; however, it has also been detected in the cytoplasm (Kalifa et al., 2004a). ASR gene expression pattern varies between different plant species. Transcripts for these genes accumulate during senescence, fruit ripening, and/or seed and pollen maturation. They also respond to environmental stress conditions, such as water deficit, salt, cold, and limited light (Silhavy et al., 1995; Padmanabhan et al., 1997; Doczi et al., 2005). There is also evidence of regulation by sugar, although for some of them this has not been confirmed (Carrari et al., 2004), and, as suggested by their name, gene expression can be induced by ABA (Wang et al., 1998; Vaidyanathan et al., 1999; Cakir et al., 2003). However, the drought response of the potato (Solanum tuberosum) ortholog ASR gene (DS2) is primarily ABA independent (Silhavy et al., 1995; Doczi et al., 2005).

The organ or tissue specificity of the group 7 LEA proteins is also diverse. Their transcripts have been detected in fruits of tomato, melon (Cucumis melo), pomelo (Citrus maxima), apricot (Prunus armenaica), and grape (Vitis vinifera; Iusem et al., 1993; Canel et al., 1995; Mbeguie-A-Mbeguie et al., 1997; Hong et al., 2002; Cakir et al., 2003), in potato tubers (Frankel et al., 2007), in roots of rice (Yang et al., 2004), in leaves or stems of tomato, rice, and maize (Amitai-Zeigerson et al., 1994; Riccardi et al., 1998, 2004; Vaidyanathan et al., 1999; Maskin et al., 2008), in pollen of lily (Lilium longiflorum; Wang et al., 1998), and in developing tomato seeds (Maskin et al., 2008).

Overexpression of tomato ASR1 protein in tobacco plants resulted in increased salt tolerance (Kalifa et al., 2004b). Increased drought and salt tolerance were obtained when the lily ortholog was overexpressed in Arabidopsis (Yang et al., 2005). Maize ASR1 was proposed as a candidate gene for the quantitative trait locus for drought stress response (Jeanneau et al., 2002).

As is the case for other LEA proteins, biochemical and biophysical analysis showed that tomato ASR1 protein is disordered in aqueous solutions; however, upon binding to zinc ions, a transition from a disordered to an ordered state is induced. This transition in protein conformation can also be induced by desiccation (Goldgur et al., 2007).

OTHER HYDROPHILINS

Some years ago, we set out to investigate how widespread were proteins that shared the physicochemical characteristics of typical plant LEA proteins. We searched databases for proteins that exhibited high hydrophilicity and a high content of Gly residues. In spite of the deceivingly loose definition, hydrophilins represent less than 0.2% of the total protein of a given genome. Not only were these structural features present in plant LEA proteins, but they were shared by proteins from very diverse organisms (Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000). In spite of their common characteristics, proteins in different groups do not show an evident sequence similarity, suggesting that they do not have a common ancestor. Accordingly, our data suggest that these physicochemical characteristics have evolved independently in different protein families and in different organisms, but with the similar goal of protecting specific functions under partial dehydration. It is noteworthy that all hydrophilins from different phyla show higher expression under water-limiting conditions, imposed either by the environment or by developmental programs. This is not only the case for LEA and non-LEA hydrophilins from plants but also for hydrophilins expressed in bacterial and fungal spores or conidia (Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000) or for others that accumulate under dehydration in anhydrobiotic organisms (Tunnacliffe et al., 2005).

Although the definition for hydrophilins appears simple, it is remarkable that 92% (348 of 378) of the different typical LEA proteins described to date can be considered hydrophilins (Fig. 1), and those whose expression patterns have been characterized are responsive to conditions of low water availability.

The accumulated data from in vitro assays strongly suggest that hydrophilins are able to prevent enzyme inactivation under partial dehydration (Lin and Thomashow, 1992; Goyal et al., 2005; Grelet et al., 2005; Reyes et al., 2005). These results showed that a gradual decrease in water availability, to similar levels as those detected in plant tissues subjected to drought, leads to conformational changes in the enzymes that are associated with inactivation. These inhibitory conformational changes do not occur when hydrophilins are present before the dehydration treatment. However, when severe water limitation (greater than −50 bars) is imposed and protein aggregation is evident, hydrophilins have no protective effects, at least in target:hydrophilin ratios in which molecular chaperones are active (1:1–1:5; Reyes et al., 2005). Despite the in vitro nature of these assays, they attempt to mimic some of the characteristics of the water-loss process in plant tissues, such as the gradual decrease in water availability as well as the avoidance of total dehydration. This is considering that these proteins accumulate in response to mild water limitation. However, the possibility that at least a subset of these proteins play a protective role under fast and severe dehydration cannot be discounted. Evidence suggesting this comes from in vitro experiments in which a group 1 LEA protein from wheat or a protein from an anhydrobiotic nematode (A. avenae), similar to group 3 LEA proteins, apparently prevented protein aggregation induced by these extreme dehydration conditions when they were used in a target:LEA ratio of 1:10 up to 1:100 (Goyal et al., 2005; Chakrabortee et al., 2007).

Although the conditions established in these in vitro experiments may be far from those prevalent in the cell, it is evident that hydrophilins possess a protective activity that mitigates the effects that water limitation conditions exert on protein conformation and function. That they carry out their protective activity in the absence of an energy source discounts the possibility that hydrophilins act as typical molecular chaperones (Goyal et al., 2005; Reyes et al., 2005). Indeed, hydrophilins are unable to protect proteins from heat shock, and they cannot recover the activity of proteins once this is lost during the dehydration process. On the other hand, there are data indicating that molecular chaperones are unable to prevent the inactivation of enzymes due to dehydration, which suggests that hydrophilins alone may be necessary to maintain protein function during this specific type of abiotic stress (Reyes et al., 2005). It is even possible that some hydrophilins may target molecular chaperones, and in combination, they could contribute to protect proteins under conditions in which dehydration is severe enough to produce protein denaturation. Indirect evidence to support such a hypothesis shows that the transcripts of different molecular chaperones are, like those of hydrophilins, accumulated in response to water limitation in different organisms (Ingram and Bartels, 1996; Bray, 1997; Bartels and Souer, 2003; Wang et al., 2004).

If we consider the high hydrophilicity and the unordered structure of hydrophilins and the fact that they can be grouped by the presence of specific conserved motifs, it is likely that their function is closely related to the high avidity for water of their amino acid residues and to the recognition of different macromolecular targets. They provide a hydrophilic surrounding to substitute for the decrease in water molecules within the microenvironment of particular macromolecules or cellular structures during water-limiting conditions, consequently preserving their integrity and function. The conserved motifs that characterize each group might be responsible for the recognition of a particular set of target molecules. Because of the unstructured nature of hydrophilins in aqueous solution and their presumed ability to attain an ordered structure specifically under conditions of water limitation (Wolkers et al., 2001; Shih et al., 2004; Goyal et al., 2005; Tolleter et al., 2007), it is plausible that hydrophilins recognize their target molecules mostly under stress situations. An additional possibility could be that some hydrophilins provide a regulatory function directed toward particular enzymes or protein complexes under low water availability. One example of this is Rmf, an E. coli hydrophilin proposed to be involved in the modulation of the translation process during stress conditions. Specifically, Rmf was identified as a ribosome modulation factor, which associates with 100S ribosome dimers (Yamagishi et al., 1993) and accumulates upon hyperosmotic stress (Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000). Similarly, STF2, a yeast hydrophilin, seems to participate in the stabilization of the complex formed between F1F0-ATPase and a protein that inhibits the activity of this enzyme upon the cessation of phosphorylation (Yoshida et al., 1990). The fact that hydrophilins show a protective effect under in vitro partial dehydration even at a target:hydrophilin ratio of 1:1 is compatible with previous ideas considering intrinsically unstructured proteins as specialized molecules to function through protein-protein interactions (Mészáros et al., 2007; Hegyi and Tompa, 2008). Although other LEA proteins have been tested for protection of enzyme activity upon heat stress (Goyal et al., 2005; Reyes et al., 2005; J.M. Colmenero-Flores, unpublished data), recent results from in vitro experiments indicate that two group 2 LEA proteins from Arabidopsis (ERD10 and ERD14) are able to prevent the heat-induced aggregation and/or inactivation of various substrates (Kovacs et al., 2008).

The intrinsic flexible nature of hydrophilins that allows them to adjust their conformation to a particular microenvironment leads to the hypothesis that different water availability levels induce different conformations in the same protein, which results in the exposure of particular motifs important for the recognition of and/or interaction with specific target molecules to preserve their function and/or promote their assembly with partners. This metamorphosis, while an appealing property, imposes new challenges in the design of experiments to identify biological targets of hydrophilins and to elucidate the mechanism of their function, particularly when most existing methodologies have been developed for structured proteins. For now, a considerable amount of work, persistence, and imagination are required to enable a complete understanding of the function, or functions, of LEA proteins and other hydrophilins.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Table S1. Group 1 LEA proteins.

Supplemental Table S2. Group 2 LEA proteins.

Supplemental Table S3. Group 3 LEA proteins.

Supplemental Table S4. Group 4 LEA proteins.

Supplemental Table S5. Group 6 LEA proteins.

Supplemental Table S6. Group 7 LEA proteins.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to B.J. Barkla and J.L. Reyes for critical reading of the manuscript and stimulating discussions and to Dr. Leon Dure III for the discovery of these proteins and his visionary work.

This work was supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología-Mexico (grant nos. 40603–Q and 50485–Q). M.B. and Y.O.-C. were supported by scholarships from Dirección General de Estudios de Posgrado-UNAM and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, respectively.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Alejandra A. Covarrubias (crobles@ibt.unam.mx).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Abba S, Ghignone S, Bonfante P (2006) A dehydration-inducible gene in the truffle Tuber borchii identifies a novel group of dehydrins. BMC Genomics 7 39–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali-Benali MA, Alary R, Joudrier P, Gautier MF (2005) Comparative expression of five LEA genes during wheat seed development and in response to abiotic stresses by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Biochim Biophys Acta 1730 56–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert P (2005) The limits and frontiers of desiccation-tolerant life. Integr Comp Biol 45 685–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert P, Oliver MJ (2002) Drying without dying. In M Black, HW Prichard, eds, Desiccation and Survival in Plants. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp 3–43

- Alsheikh MK, Heyen BJ, Randall SK (2003) Ion binding properties of the dehydrin ERD14 are dependent upon phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 278 40882–40889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsheikh MK, Svensson JT, Randall SK (2005) Phosphorylation regulated ion-binding is a property shared by the acidic subclass dehydrins. Plant Cell Environ 28 1114–1122 [Google Scholar]

- Amitai-Zeigerson H, Scolnik PA, Bar-Zvi D (1994) Genomic nucleotide sequence of tomato Asr2, a second member of the stress/ripening-induced Asr1 gene family. Plant Physiol 106 1699–1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora R, Rowland LJ, Panta GR (1997) Chill-responsive dehydrins in blueberry: are they associated with cold hardiness or dormancy transitions? Physiol Plant 101 8–16 [Google Scholar]

- Baker EH, Bradford KJ, Bryant JA, Rost TL (1995) A comparison of desiccation-related proteins (dehydrin and QP47) in pea (Pisum sativum). Seed Sci Res 5 185–193 [Google Scholar]

- Baker J, Steele C, Dure L (1988) Sequence and characterization of 6 LEA proteins and their genes from cotton. Plant Mol Biol 11 277–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels D, Souer E (2003) Molecular response of higher plants to dehydration. Top Curr Genet 4 9–38 [Google Scholar]

- Battista JR, Park MJ, McLemore AE (2001) Inactivation of two homologues of proteins presumed to be involved in the desiccation tolerance of plants sensitizes Deinococcus radiodurans R1 to desiccation. Cryobiology 43 133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bies-Ethève N, Gaubier-Comella P, Debures A, Lasserre E, Jobet E, Raynal M, Cooke R, Delseny M (2008) Inventory, evolution and expression profiling diversity of the LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) protein gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 67 107–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokor M, Csizmok V, Kovacs D, Banki P, Friedrich P, Tompa P, Tompa K (2005) NMR relaxation studies on the hydrate layer of intrinsically unstructured proteins. Biophys J 88 2030–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovskii GB, Stupnikova IV, Antipina AI, Downs CA, Voinikov VK (2000) Accumulation of dehydrin-like-proteins in the mitochondria of cold-treated plants. J Plant Physiol 156 797–800 [Google Scholar]

- Borovskii GB, Stupnikova IV, Antipina AI, Vladimirova SV, Voinikov VK (2002) Accumulation of dehydrin-like proteins in the mitochondria of cereals in response to cold, freezing, drought and ABA treatment. BMC Plant Biol 2 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo LA, Gallardo J, Navarrete A, Olave N, Martinez J, Alberdi M, Close TJ, Corcuera LJ (2003) Cryoprotective activity of a cold-induced dehydrin purified from barley. Physiol Plant 118 262–269 [Google Scholar]

- Bray EA (1997) Plant responses to water deficit. Trends Plant Sci 2 48–54 [Google Scholar]

- Brini F, Hanin M, Lumbreras V, Amara I, Khoudi H, Hassairi A, Pagès M, Masmoudi K (2007) Overexpression of wheat dehydrin DHN-5 enhances tolerance to salt and osmotic stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep 26 2017–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne JA, Dolan KM, Tyson T, Goyal K, Tunnacliffe A, Burnell AM (2004) Dehydration-specific induction of hydrophilic protein genes in the anhydrobiotic nematode Aphelenchus avenae. Eukaryot Cell 3 966–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakir B, Agasse A, Gaillard C, Saumonneau A, Delrot S, Atanassova R (2003) A grape ASR protein involved in sugar and abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 15 2165–2180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SA, Close TJ (1997) Dehydrins: genes, proteins, and associations with phenotypic traits. New Phytol 137 61–74 [Google Scholar]

- Canel C, Bailey-Serres JN, Roose ML (1995) Pummelo fruit transcript homologous to ripening-induced genes. Plant Physiol 108 1323–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrari F, Fernie AR, Iusem ND (2004) Heard it through the grapevine? ABA and sugar cross-talk: the ASR story. Trends Plant Sci 9 57–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattivelli L, Bartels D (1990) Molecular cloning and characterization of cold-regulated genes in barley. Plant Physiol 93 1504–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabortee S, Boschetti C, Walton LJ, Sarkar S, Rubinsztein DC, Tunnacliffe A (2007) Hydrophilic protein associated with desiccation tolerance exhibits broad protein stabilization function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 18073–18078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler PM, Robertson M (1994) Gene expression regulated by abscisic acid and its relation to stress tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol 45 113–141 [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Babu R, Zhang JS, Blum A, Ho T, Wu R, Nguyen HT (2004) HVA1, a LEA gene from barley confers dehydration tolerance in transgenic rice (Oryza sativa L.) via cell membrane protection. Plant Sci 166 855–862 [Google Scholar]

- Close TJ (1996) Dehydrins: emergence of a biochemical role of a family of plant dehydration proteins. Physiol Plant 97 795–803 [Google Scholar]

- Close TJ, Fenton RD, Yang A, Asghar R, DeMason DA, Crione D, Meyer NC, Moonan F (1993) Dehydrin: the protein. In TJ Close, EA Bray, eds, Plant Responses to Cellular Dehydration during Environmental Stress. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 104–118

- Close TJ, Kortt AA, Chandler PM (1989) A cDNA-based comparison of dehydration-induced proteins (dehydrins) in barley and corn. Plant Mol Biol 13 95–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A, Plant AL, Moses MS, Bray EA (1991) Organ-specific and environmentally regulated expression of two abscisic acid-induced genes of tomato: nucleotide sequence and analysis of the corresponding cDNAs. Plant Physiol 97 1367–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmenero-Flores JM, Campos F, Garciarrubio A, Covarrubias AA (1997) Characterization of Phaseolus vulgaris cDNA clones responsive to water deficit: identification of a novel late embryogenesis abundant-like protein. Plant Mol Biol 35 393–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmenero-Flores JM, Moreno LP, Smith C, Covarrubias AA (1999) PvLEA-18, a member of a new late-embryogenesis-abundant protein family that accumulates during water stress and in the growing regions of well-irrigated bean seedlings. Plant Physiol 120 93–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuming AC (1999) LEA proteins. In R Casey, PR Shewry, eds, Seed Proteins. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 753–780

- Curry J, Morris CF, Walker-Simmons MK (1991) Sequence analysis of a cDNA encoding a group 3 LEA mRNA inducible by ABA or dehydration stress in wheat. Plant Mol Biol 16 1073–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry J, Walker-Simmons MK (1993) Unusual sequence of group 3 LEA (II) mRNA inducible by dehydration stress in wheat. Plant Mol Biol 21 907–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danyluk J, Houde M, Rassart E, Sarhan F (1994) Differential expression of a gene encoding an acidic dehydrin in chilling sensitive and freezing tolerant Gramineae species. FEBS Lett 344 20–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danyluk J, Perron A, Houde M, Limin A, Fowler B, Benhamou N, Sarhan F (1998) Accumulation of an acidic dehydrin in the vicinity of the plasma membrane during cold acclimation of wheat. Plant Cell 10 623–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS, Jonas A, Clayton DF, George JM (1998) Stabilization of alpha-synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes. J Biol Chem 273 9443–9449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaye L, Duval M, Viguier D, Yaxley J, Job D (1997) Cloning and expression of the pea gene encoding SBP65, a seed-specific biotinylated protein. Plant Mol Biol 35 605–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delseny M, Bies-Etheve N, Carles C, Hull G, Vicient C, Raynal M, Grellet F, Aspart L (2001) Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) protein gene regulation during Arabidopsis seed maturation. J Plant Physiol 158 419–427 [Google Scholar]

- Doczi R, Kondrak M, Kovacs G, Beczner F, Banfalvi Z (2005) Conservation of the drought-inducible DS2 genes and divergences from their ASR paralogues in solanaceous species. Plant Physiol Biochem 43 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong JZ, Dunstan DI (1997) Characterization of cDNAs representing five abscisic acid-responsive genes associated with somatic embryogenesis in Picea glauca, and their responses to abscisic acid stereostructure. Planta 203 448–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztányi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I (2005) The pairwise energy content estimated from amino acid composition discriminates between folded and intrinsically unstructured proteins. J Mol Biol 347 827–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dure L (1993. a) A repeating 11-mer amino acid motif and plant desiccation. Plant J 3 363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dure L (1993. b) Structural motifs in LEA proteins. In TJ Close, EA Bray, eds, Plant Responses to Cellular Dehydration during Environmental Stress. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 91–103

- Dure L (2001) Occurrence of a repeating 11-mer amino acid sequence motif in diverse organisms. Protein Pept Lett 8 115–122 [Google Scholar]

- Dure L, Chlan C (1981) Developmental biochemistry of cottonseed embryogenesis and germination. XII. Purification and properties of principal storage proteins. Plant Physiol 68 180–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]