Abstract

Coenzyme A (CoA) is an essential cofactor in the metabolism of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms and a universal five-step pathway is utilized to synthesize CoA from pantothenate. Null mutations in two of the five steps of this pathway led to embryo lethality and therefore viable reduction-of-function mutations are required to further study its role in plant biology. In this article, we have characterized a viable Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) T-DNA mutant affected in the penultimate step of the CoA biosynthesis pathway, which is catalyzed by the enzyme phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase (PPAT). This ppat-1 knockdown mutation showed an approximately 90% reduction in PPAT transcript levels and was severely impaired in plant growth and seed production. The sum of CoA and acetyl-CoA levels was severely reduced (60%–80%) in ppat-1 seedlings compared to wild type, and catabolism of storage lipids during seedling establishment was delayed. Conversely, PPAT overexpressing lines showed, on average, approximately 1.6-fold higher levels of CoA + acetyl-CoA levels, as well as enhanced vegetative and reproductive growth and salt/osmotic stress resistance. Interestingly, dry seeds of overexpressing lines contained between 35% to 50% more fatty acids than wild type, which suggests that CoA biosynthesis plays a crucial role in storage oil accumulation. Finally, biochemical analysis of the recombinant PPAT enzyme revealed an inhibitory effect of CoA on PPAT activity. Taken together, these results suggest that the reaction catalyzed by PPAT is a regulatory step in the CoA biosynthetic pathway that plays a key role for plant growth, stress resistance, and seed lipid storage.

Coenzyme A (CoA) is an essential cofactor in numerous biosynthetic, degradative, and energy-yielding metabolic pathways (Begley et al., 2001). The synthesis of CoA, starting from pantothenate as a precursor, occurs in five steps and the corresponding biosynthetic enzymes have been cloned in both prokaryotes and higher eukaryotes (Begley et al., 2001; Daugherty et al., 2002; Kupke et al., 2003; Leonardi et al., 2005). The universal pathway for biosynthesis of CoA from pantothenate is initiated by phosphorylation of this precursor to generate 4′-phosphopantothenate, which is catalyzed by pantothenate kinase (PANK; CoaA). In unicellular organisms and animal systems, the rate of CoA biosynthesis appears to be regulated by feedback inhibition of PANK. Recently, two plant PANKs, namely, AtPANK1 and AtPANK2, have been characterized in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and, as a result, a pank1-1pank2-1 double mutant was found to be embryo lethal (Tilton et al., 2006). The second step of CoA biosynthesis involves the addition of Cys to 4′-phosphopantothenate mediated by 4′-phospho-N-pantothenoyl-Cys synthetase (PPCS; CoaB). In the next step, 4′-phospho-N-pantothenoyl-Cys decarboxylase (PPCDC; CoaC) catalyzes the generation of 4′-phosphopantetheine. Two Arabidopsis genes, AtHAL3A and AtHAL3B, encode essential PPCDC enzymes, and combined inactivation of both genes aborted embryogenesis at the early globular stage (Rubio et al., 2006). The penultimate step in the CoA biosynthetic pathway is catalyzed by the enzyme 4′-phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase (PPAT; CoaD), which catalyzes the reversible adenylation of 4′-phosphopantetheine to form 3′-dephospho-CoA (dPCoA) and pyrophosphate (PPi; see Fig. 5A). Finally, dephospho-CoA kinase (DPCK; CoaE) catalyzes the last step of the CoA biosynthetic pathway, which involves the phosphorylation of the 3′-hydroxy group of the Rib sugar moiety from dPCoA to form CoA and ADP.

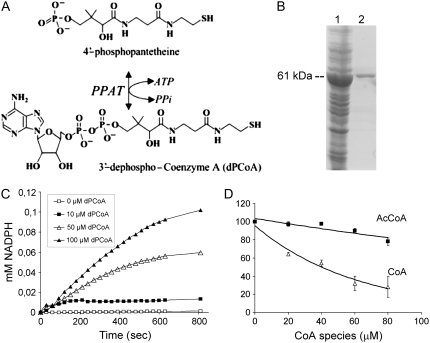

Figure 5.

Biochemical characterization of PPAT enzyme in the reverse reaction. A, Scheme of the reversible reaction catalyzed by PPAT. B, Recombinant MBP-PPAT fusion protein in E. coli crude extract (1) and after purification by affinity chromatography (2). The apparent molecular mass of the protein is indicated. C, Enzyme kinetics of recombinant MBP-PPAT. The enzyme (40 nm) was assayed as described in “Materials and Methods” and the reduction rate of NADP to NADPH was monitored by measuring A340 wavelength. Regression analysis of the data (R2 = 0.99) was performed using Microsoft Excel software to calculate the initial velocity (V0) of the reaction at different substrate concentrations. D, Inhibition of PPAT activity by CoA (Δ) and AcCoA (▪). Values are averages ± sd for two independent experiments. Regression analysis of the data was performed using Graph Pad 4.0 software.

Considering the central role of CoA in plant metabolism, the analysis of mutants impaired in CoA biosynthesis has received limited attention (Rubio et al., 2006; Tilton et al., 2006). Recently, we reported that a hal3a-1hal3b-1 double mutant was embryo lethal, whereas seedlings that were null for HAL3A and heterozygous for HAL3B (aaBb hal3 mutant) displayed a Suc-dependent phenotype for seedling establishment (Rubio et al., 2006). In this article, we have focused on the next step of CoA biosynthesis, which is catalyzed by the enzyme PPAT. Studies in Escherichia coli and mammals of the intermediates in CoA biosynthesis have shown that, in addition to control of the synthesis at the level of PANK, further modulation of flux through the pathway occurs at PPAT as both pantothenate and 4′-phosphopantetheine can accumulate in the cell under limiting conditions for CoA biosynthesis (Jackowski and Rock, 1984; Rock et al., 2000). In humans, both PPAT and DPCK activity are encoded in a single gene that gives rise to a bifunctional enzyme named CoA synthase (Daugherty et al., 2002). In contrast, plants have separate monofunctional enzymes encoded by distinct genes (Kupke et al., 2003). The Arabidopsis PPAT gene product was identified by its strong homology to the human counterpart in CoA synthase and its biochemical activity has been confirmed in vitro (Kupke et al., 2003). In this article, we have performed analyses of gain-of-function and reduction-of-function mutants in PPAT, providing evidence on its role in plant growth, osmotic stress resistance, and lipid metabolism.

RESULTS

Isolation and Characterization of a T-DNA Insertion Mutation in the Arabidopsis PPAT Gene

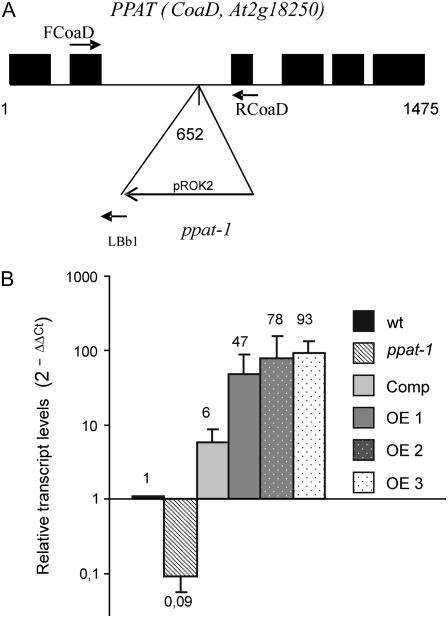

A T-DNA disrupted allele of PPAT was identified at the SALK collection (http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress), corresponding to donor stock number SALK_093728 and designated ppat-1 (Fig. 1A). The T-DNA insertion in ppat-1 is localized to the second intron, 652 nucleotides downstream of the ATG start codon. Three additional T-DNA lines localized in the vicinity of the PPAT transcription unit were identified, but they did not affect significantly PPAT gene expression (data not shown). The ppat-1 mutant showed an approximately 90% reduction in the expression of PPAT compared to wild type (Fig. 1B). Quantitative real-time-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis consistently detected residual approximately 10% expression, which suggests that splicing of the intron where the T-DNA was inserted occurred to some extent.

Figure 1.

Molecular characterization of the ppat-1 mutant. A, Scheme of the PPAT gene and localization of T-DNA insertion. The numbering begins at the ATG translation start codon. The T-DNA left border primer (LBb1) that was used to localize the T-DNA insertion as well as primers used for qRT-PCR analysis (FCoaD, RCoaD) are indicated. Black boxes represent exons. B, qRT-PCR analysis of PPAT expression in mRNAs prepared from 10-d-old seedlings (whole tissue) of wild type, ppat-1, Comp line, and PPAT OE lines. Data are averages ± sd from three independent experiments. Expression of β-actin-8 was used to normalize data.

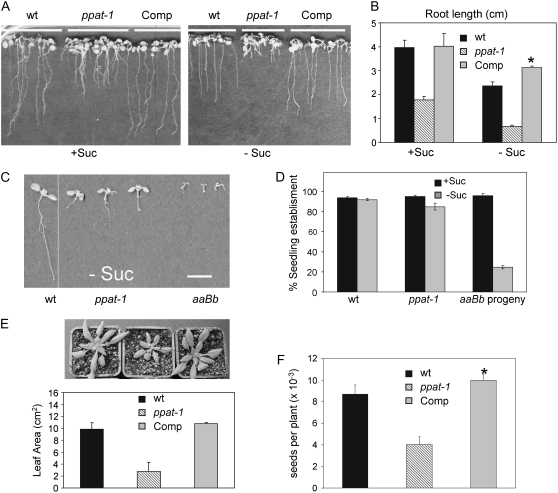

An impairment in vegetative growth was observed for ppat-1 seedlings both in medium lacking or supplemented with 1% Suc (Fig. 2, A and B); nevertheless, the phenotype was not so severe as those of aaBb hal3 seedlings in medium lacking Suc (Rubio et al., 2006; Fig. 2C), and, in contrast to aaBb hal3 progeny, seedling establishment was not compromised in ppat-1 (Fig. 2D). The ppat-1 mutant was viable, but the percentage of survival after transferring seedlings germinated in Murashige and Skoog plates to soil was below 30% (data not shown). Subsequent growth in soil and seed production of ppat-1 plants was severely reduced compared to wild-type plants (Fig. 2, E and F; see Fig. 3D). In general, reproductive growth was impaired in ppat-1 plants because fewer inflorescence stems were present per plant (see Fig. 3D). To verify that the observed phenotypes were a consequence of impaired PPAT expression, we generated complementation lines for ppat-1. To this end, the PPAT cDNA was placed under the control of the 35S promoter and introduced into ppat-1 via Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Primary transformants (T1) were selected for hygromycin resistance and a T3 population homozygous for the transgene was obtained. Introduction of the wild-type PPAT allele complemented the above-described phenotypes (Fig. 2; see Fig. 3D), which proved that a reduction-of-function mutation in PPAT was responsible for these phenotypes. qRT-PCR analysis showed that the introduction of PPAT under the control of a 35S promoter led to higher expression levels than those obtained from the native promoter (Fig. 1B). Indeed, some significant differences on root growth, seed production (Fig. 2), and fatty acid (FA) content (see Fig. 6A) were found in the complementation lines as compared to wild type.

Figure 2.

Growth phenotype of ppat-1 mutant and genetic complementation. A, Growth of wild type, ppat-1, and Comp line in medium supplemented with 1% Suc (+Suc) or lacking Suc (−Suc). B, Quantification of root growth in 5-d-old seedlings. Values are averages ± sd (n = 100). C and D, Seedling (7-d-old) growth and establishment of wild-type, ppat-1, and aaBb plants. Scale bar = 1 cm. Values in D are averages ± sd for three independent experiments (200 seeds each). E, Growth in soil of wild type, ppat-1, and Comp line, and quantification of leaf area in 21-d-old plants. Values are averages ± sd (n = 20). F, Seed production. Values are averages ± sd (n = 20). *, P < 0.05 (Student's t test) with respect to wild type.

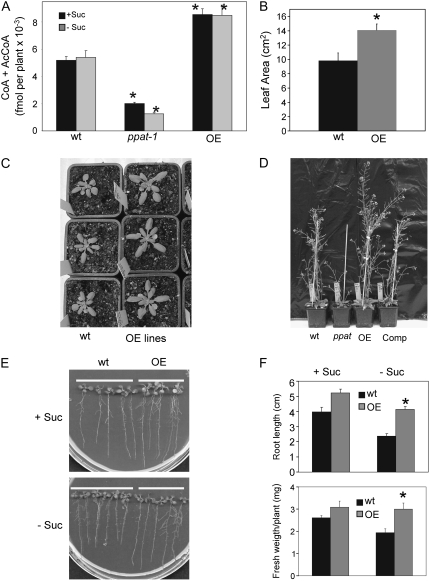

Figure 3.

Phenotype of PPAT OE lines. A, The sum of CoA and AcCoA levels was determined in 12-d-old seedlings (whole tissue) from wild type, ppat-1, and PPAT OE lines grown in medium supplemented with 1% Suc (+Suc) or lacking Suc (−Suc). Values are averages ± se from two independent experiments. Values from OE lines represent pooled data from three independent lines. B and C, Increased leaf growth in PPAT OE lines compared to wild-type plants. Quantification of leaf area and photograph of plants grown in soil for 2 weeks. Values are averages ± se (n = 20). D, Enhanced reproductive growth of OE lines as compared to wild-type plants. E, Growth of wild-type and OE lines in medium +Suc or −Suc after 12 d. F, Quantification of both root growth and fresh weight for wild-type and OE lines in medium +Suc or −Suc. A representative OE line is shown in D, E, and F. *, P < 0.01 (Student's t test) with respect to wild type.

Overexpression of PPAT Leads to Enhanced Growth and Salt/Osmotic Stress Resistance

Plants that overexpress the gene encoding the AtHAL3A PPCDC showed improved growth under salt and osmotic stress (Espinosa-Ruiz et al., 1999). Overexpression of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) HAL3 also enhanced salt and osmotic stress tolerance in cultured tobacco cells (Yonamine et al., 2004). Although these works did not prove that CoA levels were affected by the overexpression of HAL3, their results suggested that regulation of CoA levels must play an important role in the integration of plant growth and stress resistance. To test this hypothesis, we generated PPAT overexpressing (OE) lines in wild-type background. Three lines homozygous for the selection marker at the T3 generation were selected and used for further analyses. qRT-PCR analysis showed that PPAT expression in OE lines was between 45- and 90-fold higher than in wild type (Fig. 1B).

The combined amount of free CoA and acetyl-CoA (AcCoA) was determined using the spectrophotometric enzyme cycling assay described originally by Allred and Guy (1969; Fig. 3A). OE lines showed, on average, 1.6-fold higher levels of free CoA + AcCoA than wild type (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the ppat-1 mutant showed a reduction of either approximately 60% or approximately 80% compared to wild type in medium +Suc or −Suc, respectively (Fig. 3A). Whereas leaf growth was reduced in ppat-1 plants compared to wild type (Fig. 2E), OE lines showed increased leaf growth (Fig. 3, B and C). These results suggest that manipulation of CoA levels through modulation of PPAT expression correlates with plant growth. Growth rate, as estimated from the number of rosette leaves per plant in a time course, was not significantly altered in OE lines (Supplemental Fig. S1), although floral stem production was, on average, 2 d faster in OE lines compared to wild type (18 ± 1 d in OE lines; 20 ± 1 d in wild type). Additionally, reproductive growth (Fig. 3D) and seed production (Supplemental Fig. S2) were significantly higher in OE lines than wild type. Seedlings from OE lines grown in medium lacking Suc showed both higher fresh weight and root growth than wild type (Fig. 3, E and F). These differences were attenuated when plants were grown in medium supplemented with Suc (Fig. 3, E and F).

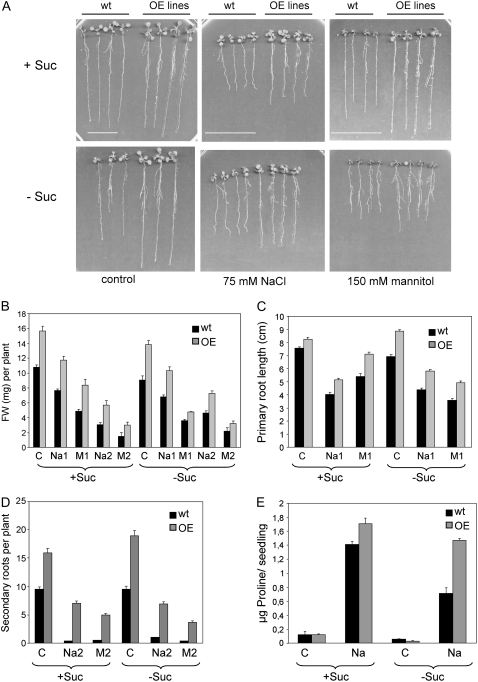

To test salt and osmotic stress sensitivity of OE lines, we transferred 7-d-old seedlings grown in medium containing 1% Suc to medium supplemented either with NaCl or mannitol, both in the absence or presence of Suc (Fig. 4). Compared to wild-type plants, OE lines showed higher fresh weight and primary root growth under salt and osmotic stress conditions (Fig. 4, B and C). Taking into account that, in the absence of stress, the OE lines also showed higher growth than wild type, the enhanced resistance to salt and osmotic stress-induced growth inhibition might be, at least partially, a consequence of the enhanced vigor observed in these lines. Indeed, the ppat-1 mutant showed both reduced growth and severe sensitivity to salt/osmotic stress (Supplemental Fig. S3). Under these conditions of low water availability, a dramatic reduction both in the number and length of secondary roots was observed in wild-type plants (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S3). OE lines suffered a less severe reduction and overall root biomass was notably higher than in wild-type plants (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S3). A partial explanation of the improved growth under osmotic stress observed in OE lines might be an enhanced accumulation of compatible osmolytes, such as Pro. Indeed, osmotic adjustment due to increased Pro deposition plays an important role in the maintenance of root elongation at low water potentials (Voetberg and Sharp, 1991). Figure 4E shows that OE lines contained approximately 2-fold higher levels of Pro than wild type in medium lacking exogenous supplementation of Suc. Additionally, Figure 4E shows that wild type was more dependent than OE lines on exogenous supplementation of Suc to increase Pro levels under salt stress.

Figure 4.

Enhanced resistance to both salt and osmotic stress in OE lines as compared to wild type. Seedlings grown in medium containing 1% Suc were transferred to medium supplemented with 75 mm NaCl (Na1), 125 mm NaCl (Na2), 150 mm mannitol (M1), or 250 mm mannitol (M2), in the presence or absence of exogenous Suc. Control seedlings (C) were transferred to medium lacking NaCl or mannitol to measure growth in the absence of stress. A representative OE line from three independent lines is shown. A, Representative photograph taken after 11 d. Scale bars = 4 cm. B, Quantification of fresh weight (FW) after 11 d. Data from control seedlings correspond to 50% of true values. C, Quantification of primary root growth after 7 d. D, Quantification of secondary root growth after 11 d. Values are averages ± se for two independent experiments (30 seedlings each). E, Determination of Pro content in wild-type and OE lines after treatment with 125 mm NaCl for 48 h.

Enzymatic Characterization of PPAT

The activity of Arabidopsis PPAT has been previously assayed by adding different combinations of recombinant enzymes to a reaction mixture containing pantothenate, ATP, Mg2+, Cys, and dithiothreitol (DTT; Kupke et al., 2003). For instance, a mixture of CoaA, CoaB, CoaC, and PPAT was able to catalyze the synthesis of dPCoA. When CoaC was omitted from the assay, dPCoA was not generated, which indicates that PPAT does not accept 4′-phosphopantothenoyl-Cys as a substrate (produced by the combined action of CoaA and CoaB). However, steady-state kinetics and biochemical regulation have not been investigated for the individual PPAT enzyme. PPAT catalyzes the reversible transfer of an adenylyl group from Mg2+-ATP to 4′-phosphopantetheine to form dPCoA and PPi (Fig. 5A). Therefore, it is possible to assay PPAT activity in the reverse direction using hexokinase and Glc-6-P dehydrogenase to couple ATP production to NADP reduction (Geerlof et al., 1999). Thus, using recombinant maltose binding protein (MBP)-PPAT (Fig. 5B), the initial rate of the reverse reaction was measured at varying concentrations of the commercial substrate dPCoA (Fig. 5C). The kinetic parameters for the reverse reaction were found to be KM (dPCoA) = 37 ± 2.1 μm, Kcat = 3.4 ± 0.2 s−1, and Vmax = 0.34 ± 0.02 μmol min−1 mg−1 protein.

The CoA metabolic intermediate 4′-phosphopantetheine is present in significant amounts both in E. coli and mammals, which suggests that PPAT catalyzes a rate-limiting step in the pathway (Jackowski and Rock, 1984; Rock et al., 2000). Such enzymes are often subjected to feedback regulation by end products of the pathway. Therefore, we have examined the effect of CoA and AcCoA on PPAT activity (Fig. 5D). Whereas AcCoA had almost no effect on PPAT activity up to 40 μm, CoA had an IC50 = 38.6 ± 1.9 μm, which is close to the Km for dPCoA.

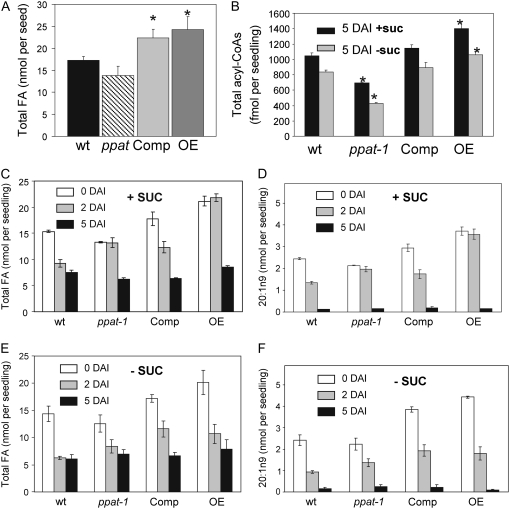

FA and Acyl-CoA Measurements

The FA content in dry seed from wild type, ppat-1, complemented (Comp), and OE lines was analyzed (Fig. 6A). FA content per seed in ppat-1 appeared lower than in wild type, although it was not statistically significant (P < 0.15). Therefore, although seed yield per plant was lower for ppat-1 plants, normal oil deposition within individual seeds occurred during seed development. A statistically significant increase in total FA content was measured both in the Comp (P < 0.026) and OE (P < 0.012) lines. Individual profiling of the major FAs from Arabidopsis dry seeds showed that the OE lines contained between 35% to 50% more FAs, namely, oleic, linoleic, linolenic, and eicosenoic acid, than wild-type seeds (Supplemental Fig. S4). Measurement of the total acyl-CoA pool was performed at 5 d after imbibition (DAI) both in medium lacking or supplemented with Suc as described by Larson and Graham (2001). In agreement with previous results (Rubio et al., 2006), Suc supplementation led to stimulation of acyl-CoA biosynthesis compared to medium lacking Suc (Fig. 6B). Total acyl-CoA levels in ppat-1 were approximately 68% and 50% of wild-type levels at 5 DAI in medium +Suc and −Suc, respectively. In contrast, PPAT OE lines contained approximately1.4 and 1.3-fold higher levels of acyl-CoAs than wild type in medium +Suc and −Suc, respectively. These changes broadly mimicked those observed for CoA and AcCoA levels in older plants in these lines (Fig. 3), indicating a relationship between free CoA availability and the size of the acyl-CoA pool.

Figure 6.

Measurements of FAs and acyl-CoAs. A, Total FA content in dry seeds of the indicated genotypes. B, Acyl-CoA content in seedlings grown +1% Suc or −Suc at 5 DAI. C and E, Total FA content at 0, 2, and 5 DAI from seedlings grown +1% Suc or −Suc, respectively. D and F, Eicosenoic acid content at 0, 2, and 5 DAI from seedlings grown +Suc or −Suc, respectively. Values are averages ± sd for five separate determinations, expressed on a per-seed/seedling basis. *, P < 0.03 (Student's t test) when compared with data from each genotype and wild type in the same growth conditions.

A time course analysis of the FA content from the different genetic backgrounds at 0, 2, and 5 DAI in medium supplemented with Suc was performed (Fig. 6C). Suc supplementation leads to slower consumption of the reserve lipids (Eastmond et al., 2000; Martin et al., 2002), and this delay was notably increased both in ppat-1 and OE lines at 2 DAI, where FA consumption was stalled (Fig. 6C). In particular, the level of the storage triacylglycerol-specific FA, eicosenoic acid (20:1n9), decreased approximately 40% in wild-type seedlings at 2 DAI, whereas almost no reduction was observed in the ppat-1 mutant and OE lines (Fig. 6D). The accumulation of 20:1n9 in ppat-1 and OE lines suggests that early FA catabolism was stalled under these germination conditions in contrast to the sharp catabolism observed in wild type. However, 20:1n9 had been mostly consumed at 5 DAI, which suggests that only early use of reserve lipids was compromised in these lines. In medium lacking exogenous Suc, faster consumption of FAs was observed in the different genotypes (Fig. 6, E and F). The severe impairment of FA catabolism at 2 DAI reported above for ppat-1 and OE lines was not observed in medium lacking exogenous Suc; however, delayed consumption of 20:1n9 was found in ppat-1 compared to wild type. Thus, the level of eicosenoic acid decreased approximately 60% in wild-type seedlings at 2 DAI, whereas approximately 40% reduction was observed in the ppat-1 mutant (Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

A universal five-step pathway is followed both by bacteria and eukaryotic organisms to synthesize CoA from pantothenate. In plants, double null mutations that lead to a complete blockade of either the first or third step of the CoA biosynthetic pathway (i.e. PANK and PPCDC activities) have been reported to be embryo lethal (Rubio et al., 2006; Tilton et al., 2006). Although these works have established the essential nature of this pathway, either the embryo-lethal phenotype or the genetic segregation of the aaBb mutant made further study of the pathway difficult. Additionally, mutants affected in the enzymes that catalyze the three remaining steps of the pathway have not been described.

In this article, we took advantage of a viable reduction-of-function mutation and gain-of-function lines that affect the penultimate step of the CoA biosynthetic pathway to study its impact on plant growth, stress response, and lipid metabolism. The results show that PPAT plays an important role in determining CoA levels. Additionally, we showed that PPAT function correlated with plant growth and stress resistance and enhancement of CoA biosynthesis through overexpression of PPAT led to plants with higher vigor and stress resistance than wild-type plants. In contrast, the ppat-1 mutant hereby studied showed a remarkable impairment in growth, which was apparent both in the absence or presence of exogenous Suc. However, the remaining expression of PPAT was sufficient for seedling establishment, although further vegetative and reproductive growth, as well seed yield, were severely impaired compared to wild-type plants. These phenotypes are likely a reflection of the key role played by CoA in a multitude of enzymatic reactions, such as the oxidation of FAs, carbohydrates, and amino acids, as well as many biosynthetic reactions (Begley et al., 2001). Growth defects of ppat-1 were complemented upon introduction of a wild-type PPAT copy under the control of the 35S promoter. Most morphological features from complemented lines were similar to wild type, although significant differences were found for root growth, seed production, and FA content, somehow resembling a weak OE line.

Overexpression of PPAT led to enhanced vegetative growth compared to wild type. Thus, during photoautotrophic growth in soil, both vegetative and reproductive growth was higher in OE lines than in wild-type plants (Fig. 3). Similarly, both root growth and fresh weight were higher in seedlings from OE lines grown in vitro in the absence of Suc. Increased root biomass is usually associated with enhanced drought tolerance (Park et al., 2005; Verslues et al., 2006). OE lines, which showed higher root growth than wild type under nonstressed conditions, also showed higher primary and secondary root growth than wild-type plants under stress conditions. As a result, better integration of plant growth with environmental stress was found in these OE lines. Thus, water stress avoidance through increased root biomass can explain the better performance under stress of the OE lines. Additionally, stress tolerance might be achieved through both compatible solute accumulation and different metabolic changes that avoid cellular damage caused by water loss. Interestingly, upon osmotic stress, 2-fold higher levels of Pro were synthesized in OE lines than wild type in medium lacking exogenous Suc (Fig. 4E). Exogenous Suc stimulated 2-fold the synthesis of Pro in wild type, whereas OE lines were less dependent than wild type on exogenous supplementation of Suc to synthesize Pro. This fact is clearly advantageous to cope with water stress as carbon reduction and phloem transport are impaired under these conditions (Wardlaw, 1967; Tully et al., 1979). Pro is mainly synthesized through a Glu-derived pathway and therefore the carbon skeleton backbone is derived from the citric acid cycle. PPAT OE lines have higher levels of CoA and AcCoA than wild type, which might enhance the synthesis of the different intermediates of the citric acid cycle.

PPAT catalyzes a secondary regulatory step in CoA biosynthesis after the PANK master regulatory point (Jackowski and Rock, 1984; Rock et al., 2000, 2003). Enhancing flux of the CoA biosynthetic pathway in E. coli through introduction of a PANK version that is refractory to inhibition by CoA led to higher accumulation of 4′-phosphopantetheine (the substrate of PPAT) than CoA, which illustrates that PPAT is a second site for regulation of CoA biosynthesis after PANK (Rock et al., 2003). In mammals, 4′-phosphopantetheine accumulates as the second most abundant metabolite of the CoA pathway after pantothenate, which suggests that both PPAT and PANK catalyze rate-limiting steps in CoA biosynthesis (Rock et al., 2000). Transient overexpression of PANK1β abolished the accumulation of pantothenate and resulted in at least a 10-fold increase of intracellular CoA levels, although also a 3-fold accumulation of 4′-phosphopantetheine was measured (Rock et al., 2000). Arabidopsis PPAT OE lines contained increased levels of CoA species (Figs. 3A and 6E), which indicates that PPAT limits CoA production in plants to some extent. Unfortunately, PPAT activity could not be demonstrated directly in Arabidopsis seedlings or leaves either in crude plant extracts or after partial purification through Sephadex G-25 gel filtration and ammonium sulfate precipitation (data not shown). The presumably low abundance of PPAT, together with background contaminants (PPAT is usually assayed by following ATP or PPi production) might explain the failure to detect PPAT activity in plant extracts. For instance, the activity of a plant enzyme involved in pantothenate biosynthesis could only be detected in purified mitochondria at specific activities of 0.5 nmol/min mg protein (Ottenhof et al., 2004). In contrast, we could easily measure PPAT activity using recombinant protein and provide steady-state kinetic parameters of the enzyme (Fig. 5). The Kcat for PPAT (3.4 s−1) was comparable to that reported for E. coli PPAT (3.3 s−1) and the bifunctional pig liver enzyme (7.7 s−1), whereas the Km of Arabidopsis PPAT for dPCoA (37 μm) was notably higher than in bacterial and mammalian enzymes (7 and 11 μm, respectively; Geerlof et al., 1999; Aghajanian and Worrall, 2002).

Finally, an inhibitory effect of CoA (IC50 = 38 μm) on PPAT activity was found. It is difficult to precisely estimate the concentration of free CoA in different plant tissues at different developmental stages to evaluate the physiological relevance of this CoA effect on PPAT activity (Tumaney et al., 2004). In spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves, the extraplastid AcCoA concentration (likely dominated by the cytosolic pool) is of the order of 40 to 65 μm (Tumaney et al., 2004). AcCoA is present in large excess over free CoA in seeds, but in spinach leaves or green silique walls both CoA species are in the same order of magnitude (Gibon et al., 2002; Tumaney et al., 2004). In addition, the IC50 of CoA on PPAT activity is quite close to the Km for the substrate dPCoA. Therefore, it seems reasonable that CoA has an inhibitory effect on PPAT activity under physiological conditions that might act as a negative feedback regulatory mechanism. CoA is indeed tightly bound to the purified E. coli enzyme (Geerlof et al., 1999), and the crystal structure of E. coli PPAT complexed with dPCoA, 4′-phosphopantetheine, or CoA has been solved (Izard and Geerlof, 1999; Izard, 2002, 2003). Analysis of the PPAT:CoA structure reveals that CoA binds to the active site in a distinct way to dPCoA and 4′-phosphopantetheine (Izard, 2003). As a result, CoA is not a substrate for PPAT and its binding to PPAT suggests negative feedback regulation on PPAT activity as has been already established for PANK (Rock et al., 2003).

The ppat-1 mutation had a modest effect on the accumulation of total FAs per seed, whereas overexpression of PPAT resulted in a 35% to 50% increase of some FAs with respect to wild type (Supplemental Fig. S4). Impairment of CoA biosynthesis in the aaBb hal3 mutant also had no major impact on the accumulation of FAs per seed (Rubio et al., 2006). However, both ppat-1 and aaBb hal3 mutants show a reduced seed yield per plant and therefore FA yield per plant was reduced more than 50% in both cases. These results suggest that the residual expression of PPAT and HAL3B throughout plant life provided sufficient CoA supply to get normal oil deposition per individual seed at the expense of reduced FA yield per plant. Although seedling establishment was not prevented in ppat-1, as reported for aaBb hal3 (Rubio et al., 2006), severe impairment for early seedling growth was observed when compared to wild-type seedlings (Fig. 2C). Early lipid catabolism was stalled in ppat-1 when the medium was supplemented with exogenous Suc; however, in medium lacking exogenous Suc, the ppat-1 mutant did not show such dramatic phenotype, although the use of eicosenoic acid was slower than in wild type (Fig. 6). The delay in FA consumption in ppat-1 might be attributed to impairment of β-oxidation due to diminished CoA biosynthesis. In contrast, the unexpected delay in FA consumption observed in the OE line suggests that enhanced CoA biosynthesis may lead to either more efficient use of exogenous Suc as an energy source and/or increased sensitivity to sugar signaling related inhibition of storage lipid catabolism.

Finally, the enhanced seed production of Arabidopsis PPAT OE lines, together with the higher accumulation of FAs per seed, suggest that boosting CoA biosynthesis might be an approach to engineer crop seeds with higher oil yield. Improved production of vegetal oils both for feeding and biodiesel use are of obvious interest. Additionally, the enhanced vegetative and reproductive growth as well as the concomitant improvement in osmotic stress resistance of PPAT OE lines might also serve to engineer crops with higher biomass production and to offer long-term sustainable solutions to agricultural land use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants were routinely grown under greenhouse conditions in pots containing 1:3 vermiculite:soil. For in vitro culture, seeds were surface sterilized by treatment with 70% ethanol for 20 min, followed by commercial bleach (2.5% sodium hypochlorite) containing 0.05% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and, finally, four washes with sterile distilled water. Seeds were sowed on Murashige and Skoog (1962) plates composed of Murashige and Skoog basal salts, 0.1% MES acid, 1% agar, and pH adjusted to 5.7 with KOH before autoclaving. When stated, 1% Suc was included in the medium. Stratification of the seeds was conducted in the dark at 4°C for 3 d. After stratification (=0 DAI), plates were transferred to a controlled-environment growth chamber at 22°C under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod at 80 to 100 μE m−2 s−1.

Mutant Isolation

A line (Columbia background) containing a single T-DNA insertion in PPAT (At2g18250) was identified from the SALK T-DNA collection (Alonso et al., 2003) corresponding to donor stock number SALK_093728. To identify individuals homozygous for the T-DNA insertion, genomic DNA was obtained from kanamycin-resistant (50 μg/mL) seedlings and submitted to PCR genotyping using the following primers: 5′-GGGAGTCTGTGATGGCCCAAT and 5′-CTTGACATAGGTCTCCACATTA. As T-DNA left border primer of the pROK2 vector, we used the following: 5′-GCCGATTTCGGAACCACCATC. The T-DNA-tagged mutant line was backcrossed once with the wild type, verified by DNA gel-blot hybridization and also by segregation analysis of the encoded antibiotic resistance gene.

Generation of Comp and OE Lines

The coding sequence of At2g18250 cDNA (obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center [ABRC]; clone U61663) was PCR amplified using the following pair primers: FCoaD, 5′-GGATCCATGGCAGCTCCGGAAGATTC and RCoaD, 5′-GGATCCTCATGATGCTTTTTCTTCTG. The PCR product was cloned into the pCR8/GW/TOPO entry vector (Invitrogen) and recombined by LR reaction into the pMDC32 destination vector (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003). The pMDC32-35S:PPAT construct was transferred to Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 (pGV2260; Deblaere et al., 1985) by electroporation and used to transform ppat-1 mutant (Comp lines) and wild-type plants (OE lines). Seeds of transformed plants were harvested and plated on hygromycin (20 μg/mL) selection medium to identify T1 transgenic plants. T3 progeny that were homozygous for the selection marker were used for further studies.

Seedling Establishment and Stress Assays

Seedling establishment of the different genetic backgrounds was scored as the percentage of seeds that developed green expanded cotyledons and the first pair of true leaves. Salt and osmotic stress tolerance assays were performed by transferring 7-d-old seedlings grown in medium containing Suc to medium supplemented with 75 mm NaCl, 125 mm NaCl, 150 mm mannitol, or 250 mm mannitol, respectively. Seedlings were grown vertically for 7 to 11 d and periodically the plates were scanned on a flatbed scanner to produce image files suitable for quantitative analysis using the National Institutes of Health Image software (ImageJ; version 1.37).

Determination of Pro Content

Pro content was determined by HPLC/mass spectrometry (MS) in plant extracts prepared in 80% ethanol from seedlings that were either mock- or 125 mm NaCl-treated for 48 h. Free amino acids in extracts were derivatized to their isobutylchloroformate derivatives as described by Husek (1991) and analyzed by liquid chromatography-MS as their MS2 fragments.

RNA Analyses

Whole-plant tissue was collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using a Qiagen RNeasy plant mini kit and 1 μg of the RNA solution obtained was reverse transcribed using 0.1 μg oligo(dT)15 primer and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Roche) to finally obtain a 40-μL cDNA solution. qRT-PCR amplifications and measurements were performed using an ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). The sequences of the primers used for PCR amplifications were as follows: for PPAT, forward 5′-GGGAGTCTGTGATGGCCCAAT and reverse 5′-CTTGACATAGGTCTCCACATTA; and for β-actin-8 (At1g49420), forward 5′-AGTGGTCGTACAACCGGTATTGT and reverse 5′-GAGGATAGCATGTGGAAGTGAGAA.

qRT-PCR amplifications were monitored using Eva-Green fluorescent stain (Biotium). Relative quantification of gene expression data was carried out using the 2−ΔΔCT or comparative CT method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Expression levels were normalized using the CT values obtained for the β-actin-8 gene. The presence of a single PCR product was further verified by dissociation analysis in all amplifications. All quantifications were made in triplicate on RNA samples.

PPAT Enzyme Assay

PPAT activity was assayed in the reverse direction using hexokinase and Glc-6-P dehydrogenase to couple ATP production to NADP reduction (Geerlof et al., 1999). The assay mixture contained 0.1 mm dPCoA, 2 mm PPi, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm NADP+, 5 mm Glc, 1 mm DTT, 4 units of hexokinase, and 1 unit of Glc-6-P dehydrogenase in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8. Recombinant PPAT was obtained as a fusion protein with MBP. To this end, the coding sequence of PPAT was excised from the pCR8/GW/TOPO entry vector using BamHI digestion and cloned into pMalc2. Expression of recombinant MBP-PPAT was induced with 1 mm isopropylthio-β-galactoside in Escherichia coli DH5a cells and the fusion protein was purified by amylose affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer's instructions (New England Biolabs).

Enzyme assays were carried out at 25°C and the increase in A340 was monitored. One unit of activity corresponds to the formation of 1 μmol of product/min using an extinction coefficient for NADPH of 6,220 m−1 cm−1. Rates were corrected for background reduction of NADP.

Determination of AcCoA and CoA

AcCoA and CoA were determined basically as described in Gibon et al. (2002) with minor modifications. Tissue samples (100–200 mg fresh weight) were powdered using mortar and pestle and extracted with (100–200 μL) of 16% TCA. After centrifugation, the supernatant was brought to pH 6 to 7 by the addition of 2 m Tris base. The sum of CoA and AcCoA was determined using the spectrophotometric enzyme cycling assay described originally by Allred and Guy (1969). Aliquots of 20 μL of extract were disposed into a microplate and 150 μL of 100 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, containing 0.25 μmol DTT and 12.5 μmol malate were added and incubated for 10 min. Next, 80 μL of a mixture containing 0.25 μmol DTT, 0.2 μmol NAD+, 0.6 μmol acetyl phosphate, 2.5 units phosphotransacetylase, 1.25 units citrate synthase, and 3 units malate dehydrogenase in 100 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, were added, the reaction mixture was incubated at 25°C for 20 min, and absorbance was read at 340 nm. Calibration curves using CoA and AcCoA standards (ranging from 0.5–10 pmol) were included with every set of determinations.

FA and Acyl-CoA Profiling

Lipids from 20 dry seeds per replica were extracted and transmethylated to their FA methyl esters (FAMEs) together with tripentadecanoin as an internal standard using a one-step procedure (Browse et al., 1986). FAMEs were dissolved in hexane and 2-μL aliquots injected for gas chromatography-flame ionization detector analysis using a BPX70 60 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.25 μm film thickness capillary column (SGE) and a CE Instruments GC8000 Top GC (Thermoquest). Injection was made into a hydrogen carrier gas stream at 1.3 mL min−1 (average linear velocity 35 cm s−1) at a 30:1 split ratio. Temperature was ramped as follows: 110°C isothermal 1 min; 7.5°C min−1 to 260°C; cool down 70°C min−1 to 110°C; total analysis time, 23 min. FAMEs were identified by comparison to a 37 FAME mix (Supelco). One hundred seedlings per replica (approximately 3 mg for 0 DAI, 20 mg for 2 DAI, and 30 mg for 5 DAI seedlings) were extracted for quantitative acyl-CoA analysis by HPLC with fluorescence detection of acyl etheno-CoA derivatives (Larson and Graham, 2001; with modifications described by Larson et al., 2002). The lipid portion of the acyl-CoA extracts was used for FA determinations as described above.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Growth rate in soil of wild type, ppat-1, Comp, and OE lines.

Supplemental Figure S2. Higher seed production from OE lines compared to wild type.

Supplemental Figure S3. Reduced stress tolerance of ppat-1 mutant and higher generation of secondary roots in OE lines as compared to wild type.

Supplemental Figure S4. Content of major FAs from Columbia wild type, ppat-1, Comp, and OE lines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Ecker and the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory for providing the sequence-indexed Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants, and ABRC/Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre for distributing these seeds as well as the PPAT cDNA clone U61663. We thank Valeria Gazda for extensive technical assistance in the acyl-CoA analyses.

This work was supported by Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (grant nos. BIO2002–03090 and BIO2005–01760) and by Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (fellowship to S.R.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Pedro L. Rodriguez (prodriguez@ibmcp.upv.es).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Aghajanian S, Worrall DM (2002) Identification and characterization of the gene encoding the human phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase and dephospho-CoA kinase bifunctional enzyme (CoA synthase). Biochem J 365 13–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allred JB, Guy DG (1969) Determination of coenzyme A and acetyl CoA in tissue extracts. Anal Biochem 29 293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, et al (2003) Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley TP, Kinsland C, Strauss E (2001) The biosynthesis of coenzyme A in bacteria. Vitam Horm 61 157–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browse J, McCourt PJ, Somerville CR (1986) Fatty acid composition of leaf lipids determined after combined digestion and fatty acid methyl ester formation from fresh tissue. Anal Biochem 152 141–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MD, Grossniklaus U (2003) A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol 133 462–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty M, Polanuyer B, Farrell M, Scholle M, Lykidis A, Crecy-Lagard V, Osterman A (2002) Complete reconstitution of the human coenzyme A biosynthetic pathway via comparative genomics. J Biol Chem 277 21431–21439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblaere R, Bytebier B, De Greve H, Deboeck F, Schell J, Van Montagu M, Leemans J (1985) Efficient octopine Ti plasmid-derived vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer to plants. Nucleic Acids Res 13 4777–4788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond PJ, Germain V, Lange PR, Bryce JH, Smith SM, Graham IA (2000) Postgerminative growth and lipid catabolism in oilseeds lacking the glyoxylate cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97 5669–5674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Ruiz A, Belles JM, Serrano R, Culianez-Macia FA (1999) Arabidopsis thaliana AtHAL3: a flavoprotein related to salt and osmotic tolerance and plant growth. Plant J 20 529–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerlof A, Lewendon A, Shaw WV (1999) Purification and characterization of phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 274 27105–27111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon Y, Vigeolas H, Tiessen A, Geigenberger P, Stitt M (2002) Sensitive and high throughput metabolite assays for inorganic pyrophosphate, ADPGlc, nucleotide phosphates, and glycolytic intermediates based on a novel enzymic cycling system. Plant J 30 221–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husek P (1991) Amino acid derivatization and analysis in five minutes. FEBS Lett 280 354–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard T (2002) The crystal structures of phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase with bound substrates reveal the enzyme's catalytic mechanism. J Mol Biol 315 487–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard T (2003) A novel adenylate binding site confers phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase interactions with coenzyme A. J Bacteriol 185 4074–4080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard T, Geerlof A (1999) The crystal structure of a novel bacterial adenylyltransferase reveals half of sites reactivity. EMBO J 18 2021–2030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski S, Rock CO (1984) Metabolism of 4′-phosphopantetheine in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 158 115–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupke T, Hernandez-Acosta P, Culianez-Macia FA (2003) 4′-phosphopantetheine and coenzyme A biosynthesis in plants. J Biol Chem 278 38229–38237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson TR, Edgell T, Byrne J, Dehesh K, Graham IA (2002) Acyl CoA profiles of transgenic plants that accumulate medium-chain fatty acids indicate inefficient storage lipid synthesis in developing oilseeds. Plant J 32 519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson TR, Graham IA (2001) Technical advance: a novel technique for the sensitive quantification of acyl CoA esters from plant tissues. Plant J 25 115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi R, Zhang YM, Rock CO, Jackowski S (2005) Coenzyme A: back in action. Prog Lipid Res 44 125–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin T, Oswald O, Graham IA (2002) Arabidopsis seedling growth, storage lipid mobilization, and photosynthetic gene expression are regulated by carbon:nitrogen availability. Plant Physiol 128 472–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol Plant 15 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Ottenhof HH, Ashurst JL, Whitney HM, Saldanha SA, Schmitzberger F, Gweon HS, Blundell TL, Abell C, Smith AG (2004) Organisation of the pantothenate (vitamin B5) biosynthesis pathway in higher plants. Plant J 37 61–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Li J, Pittman JK, Berkowitz GA, Yang H, Undurraga S, Morris J, Hirschi KD, Gaxiola RA (2005) Up-regulation of a H+-pyrophosphatase (H+-PPase) as a strategy to engineer drought-resistant crop plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102 18830–18835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock CO, Calder RB, Karim MA, Jackowski S (2000) Pantothenate kinase regulation of the intracellular concentration of coenzyme A. J Biol Chem 275 1377–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock CO, Park HW, Jackowski S (2003) Role of feedback regulation of pantothenate kinase (CoaA) in control of coenzyme A levels in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 185 3410–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio S, Larson TR, Gonzalez-Guzman M, Alejandro S, Graham IA, Serrano R, Rodriguez PL (2006) An Arabidopsis mutant impaired in coenzyme A biosynthesis is sugar dependent for seedling establishment. Plant Physiol 140 830–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton GB, Wedemeyer WJ, Browse J, Ohlrogge J (2006) Plant coenzyme A biosynthesis: characterization of two pantothenate kinases from Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 61 629–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully RE, Hanson AD, Nelsen CE (1979) Proline accumulation in water-stressed barley leaves in relation to translocation and the nitrogen budget. Plant Physiol 63 518–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumaney AW, Ohlrogge JB, Pollard M (2004) Acetyl coenzyme A concentrations in plant tissues. J Plant Physiol 161 485–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verslues PE, Agarwal M, Katiyar-Agarwal S, Zhu J, Zhu JK (2006) Methods and concepts in quantifying resistance to drought, salt and freezing, abiotic stresses that affect plant water status. Plant J 45 523–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voetberg GS, Sharp RE (1991) Growth of the maize primary root at low water potentials: III. Role of increased proline deposition in osmotic adjustment. Plant Physiol 96 1125–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlaw IF (1967) The effect of water stress on translocation in relation to photosynthesis and growth. I. Effect during grain development in wheat. Aust J Biol Sci 20 25–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonamine I, Yoshida K, Kido K, Nakagawa A, Nakayama H, Shinmyo A (2004) Overexpression of NtHAL3 genes confers increased levels of proline biosynthesis and the enhancement of salt tolerance in cultured tobacco cells. J Exp Bot 55 387–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.