Abstract

Limited information exists regarding measurement, reproducibility and interrelationships of non-invasive biomarkers in smokers. We compared exhaled breath condensate (EBC) leukotriene B4 (LTB4) and 8-isoprostane, exhaled nitric oxide, induced sputum, spirometry, plethysmography, impulse oscillometry and methacholine reactivity in 18 smokers and 10 non-smokers. We assessed the relationships between these measurements and within-subject reproducibility of EBC biomarkers in smokers. Compared to non-smokers, smokers had significantly lower MMEF % predicted (mean 64.1 vs 77.7, p = 0.003), FEV1/FVC (mean 76.2 vs 79.8 p = 0.05), specific conductance (geometric mean 1.2 vs 1.6, p = 0.02), higher resonant frequency (mean 15.5 vs 9.9, p = 0.01) and higher EBC 8-isoprostane (geometric mean 49.9 vs 8.9 pg/ml p = 0.001). Median EBC pH values were similar, but a subgroup of smokers had airway acidification (pH < 7.2) not observed in non-smokers. Smokers had predominant sputum neutrophilia (mean 68.5%). Repeated EBC measurements showed no significant differences between group means, but Bland Altman analysis showed large individual variability. EBC 8-isoprostane correlated with EBC LTB4 (r = 0.78, p = 0.0001). Sputum supernatant IL-8 correlated with total neutrophil count per gram of sputum (r = 0.52, p = 0.04) and with EBC pH (r = −0.59, p = 0.02). In conclusion, smokers had evidence of small airway dysfunction, increased airway resistance, reduced lung compliance, airway neutrophilia and oxidative stress.

Keywords: smoking, exhaled breath condensate, exhaled nitric oxide, induced sputum, respiratory function tests

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is the major risk factor for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Smokers without COPD have evidence of airway inflammation, small airway dysfunction and bronchial hyperreactivity (Cosio et al 1978; Tashkin et al 1996; Stanescu et al 1998; Clark et al 2001; Saetta et al 2001). In a proportion of cases, these pathophysiological abnormalities become amplified, causing airflow obstruction. The early pathophysiological changes caused by smoking therefore form an integral part of the study of COPD.

Spirometry is routinely used to diagnose COPD. Alternative pulmonary function methods such as body plethysmography, which measures lung volumes and airway conductance, and impulse oscillometry (IOS), which measures pulmonary resistance and compliance, provide valuable additional information on pulmonary dynamics. Using these additional methods may provide evidence of the early physiological abnormalities present in smokers without airflow obstruction ie, with normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).

Non-invasive techniques such as induced sputum, exhaled breath condensate (EBC) and exhaled nitric oxide (NO) are being increasingly used to identify biomarkers that are linked to the effects of smoking and the development of airflow obstruction. Although bronchial biopsy remains the gold standard investigation of airway inflammation, these techniques have the benefit of being non-invasive, safe and easily repeatable. There is evidence that smokers without COPD have sputum neutrophilia (Pizzicini et al 1996; Chalmers et al 2001; Rytila et al 2006), increased EBC 8-isoprostane (Montuschi et al 2000) and reduced exhaled NO (Kharitonov et al 1995; Corradi et al 1999; Malinovschi et al 2006; Rytila et al 2006). Although EBC pH is known to be reduced in COPD patients (Kostikas et al 2002), this has not been studied in smokers.

Induced sputum, EBC and exhaled NO measurements have not been investigated during the same study in smokers, so it is not known whether these measurements are independent or related variables in this population group. Induced sputum, EBC and exhaled gas analysis all sample different compartments of the airways by different methods, and can be used to analyze different biological mediators that are involved in a range of inflammatory processes. For this reason, it is important to understand whether biomarkers measured by these techniques provide similar or different information about airway inflammation. For example, it is not known if airway neutrophilia is related to increased 8-isoprostane production or airway acidification in smokers.

EBC measurements can be prone to significant variability (Horvath et al 2005). Although studies have shown raised levels of EBC 8 isoprostane and LTB4 in smokers (Montuschi et al 2000; Carpagnano et al 2003), there have been concerns about the reproducibility of these assays (van Hoydonck et al 2004; Borrill et al 2005; Rahman 2005).

We report a comprehensive assessment of non-invasive biomarkers of airway inflammation (EBC, exhaled NO and induced sputum), bronchial hyperreactivity (BHR) and lung function (spirometry, plethysmography and IOS) in smokers without airflow obstruction. The primary aims of this study were 1) to compare pulmonary function and non-invasive biomarker data between smokers and non-smokers to gain a comprehensive understanding of the early physiological and inflammatory effects of cigarette smoking, and 2) to investigate the relationships between non-invasive biomarkers in smokers. We also investigated the reproducibility of EBC biomarkers in smokers.

Methods

Subjects and study design

18 current smokers (mean age 46.4 [SD 9.6], 7 male, mean pack years 25.5 [SD 10.3]) and 10 lifelong non-smoking healthy controls (mean age 44.8 [SD 15.6], 4 male) with normal lung function were recruited. Exclusion criteria were; history of asthma or atopy, FEV1 <85% predicted, FEV1/FVC <70%, respiratory tract infection within 2 weeks, any concomitant medication or major concurrent medical condition. Subjects were asked to avoid caffeine and cigarettes for 2 hours prior to each visit. Written informed consent was obtained and the study was approved by the South Manchester Medical Research Ethics Committee, Gateway House, Piccadilly South, Manchester, UK. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Subjects underwent EBC, exhaled NO, respiratory function tests (IOS, plethysmography and spirometry), methacholine challenge and induced sputum assessments in that order (visit 1). One week later, all smokers attended for repeated EBC (visit 2). EBC samples were obtained from all subjects, and were used firstly for 8-isoprostane and LTB4 analysis. After 8-isoprostane and LTB4 analysis there was sufficient sample remaining for pH analysis in all non-smokers, 17 smokers at visit 1, and 14 at visit 2. Adequate sputum samples were obtained from 16 smokers but only 2 non-smokers. Non-smokers’ sputum data was not used further. Methacholine challenge was performed in 15 smokers and all non-smokers. The relationship between non-invasive biomarkers was assessed in smokers at visit 1.

Pulmonary function and methacholine challenge

For IOS (Masterscreen IOS, Erich Jaeger, Hoechberg, Germany) subjects supported their cheeks to reduce upper airway shunting while impulses were applied during tidal breathing for 30 seconds. R5 and R20 (respiratory resistance at 5 and 20Hz respectively), X5 (reactance at 5 Hz) and RF (resonant frequency) were recorded. Airways resistance (Raw), specific conductance (sGaw), functional residual capacity (FRC), vital capacity (VC), inspiratory capacity (IC), total lung capacity (TLC) and residual volume (RV) were measured in a constant volume plethysmograph (Vmax 6200, Sensormedics, Bilthoven, Netherlands). IOS and body plethysmograph measurements were performed in triplicate and the mean calculated. Maximum expiratory flow volume measurements (FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second, FVC, forced vital capacity and MMEF, maximum mean expiratory flow) were performed using a spirometer (Super Spiro, Micromedical, Rochester, UK). Readings were performed in triplicate, with the highest measurement used.

Methacholine challenge was performed using a previously described method (Langley et al 2002). A DeVilbiss 646 nebuliser (Sunrise medical, Wollaston, UK) and a Rosenthal dosimeter (PDS research, Gravesend, UK) were used to deliver doubling doses of methacholine, administered using 3 stock concentrations (1.5 mg/ml, 12 mg/ml and 50 mg/ml; Stockport pharmaceuticals, Stockport, UK). FEV1 measurements were made immediately before the challenge procedure, one minute after the administration of saline and one minute after each dose of methacholine. Doubling doses of methacholine starting at 0.015 mg were administered until a fall of ≥20% from the post-saline FEV1 was observed or the maximum dose of methacholine (5.96 mg) had been administered.

Exhaled breath condensate

EBC was collected during tidal breathing for 10 minutes (EcoScreen, Jaeger, Hoechberg, Germany) without a nose peg as previously described (Borrill et al 2005). Samples were aliquoted into separate 200 μl tubes and frozen at −80 °C for later analysis. Argon gas was passed over the sample at 2L/min for 10 minutes to achieve gas standardisation, after which pH was measured using pH 210 meter (Hanna instruments, Bedfordshire, UK) with a Biotrode electrode (Hamilton, Nevada, US). LTB4 and 8-isoprostane were measured by enzyme immunoassays (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbour, MI, USA). All samples were analysed in triplicate. The lower limits of detection were 13 pg/ml and 5 pg/ml for LTB4 and 8-isoprostane respectively.

Exhaled nitric oxide

Exhaled nitric oxide was measured using a chemiluminescence analyser according to the ATS guidelines (American Thoracic Society 1999). The results from 5 different flow rates (10, 30, 50, 100 and 200 ml/s) were applied to one non-linear (Silkoff et al 2000) and two mixed linear and non-linear mathematical models (Pietropaoli et al 1999; Hogman et al 2002) with the following unknown variables; CawNO (concentration of NO in the airway wall), CalvNO (alveolar concentration) and DawNO (diffusing capacity of NO from the airway wall). Total maximal airway wall NO flux (J’awNO in pl/s) was also calculated as the product of CawNO and DawNO.

Induced sputum

Sputum was induced and processed as previously described (Pizzicini et al 1996). Briefly, sputum was induced using 3%, 4%, and 5% saline, inhaled in sequence for 5 min each via an ultrasonic nebulizer (Ultraneb 2000, Medix, Harlow, UK) 20 minutes after 200 mcg inhaled salbutamol. Once expectorated, the sputum was stored on ice and processed within 1 hour. Sputum was selected from saliva and treated by adding four volumes of 0.1% dithiothreitol, followed by four volumes of phosphate buffered saline (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The suspension was then filtered through 48 mcm nylon gauze (Sefar, Bury, UK) and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes. The resulting supernatant was stored at −80 °C for later analysis. Total leukocyte count and evaluation of cell viability (trypan blue exclusion method) was made and the cell suspension adjusted to 1.0 × 106/ml. Cytospin preparations were made with 50 mcl and 100 mcl of the cell suspension (Cytospin 4, Shandon, Runcorn, UK) after which slides were air dried, fixed with methanol and stained with Rapi-diff (Triangle, Skelmersdale, UK). Four hundred leukocytes were counted and the results expressed as a percentage of the total leukocyte count. Supernatant IL-8 was measured using a commercially available quantitative enzyme linked sandwich immunoassay (ELISA, R&D Systems Europe, Oxon, UK) with a lower limit of detection of 15.625 pg/ml.

Statistical analysis

PD20, sGaw, EBC 8-isoprostane, EBC LTB4, percentage eosinophil count, percentage lymphocyte count and absolute cell counts were normally distributed after natural log transformation and are expressed as geometric mean (SD). EBC pH data were not normally distributed and are expressed as median (range). All other data including supernatant IL-8, percentage neutrophil and macrophage counts were normally distributed and expressed as mean (SD). Parametric data and natural log transformed data were compared using unpaired t tests, and correlated using Pearson’s correlations. EBC pH data were compared using Mann-Whitney U test and correlated with other non-invasive biomarkers using Spearman’s correlations. Significance was defined as a p value of <0.05. Subjects who did not react to the highest dose of methacholine were assigned a PD20 of 11.92 mg (2 × maximum dose). Between day variability in smokers was analysed using the Bland Altman method expressed as mean difference and limits of agreement (Bland and Altman 1986).

Results

Comparison of smokers and non-smokers

Lung function

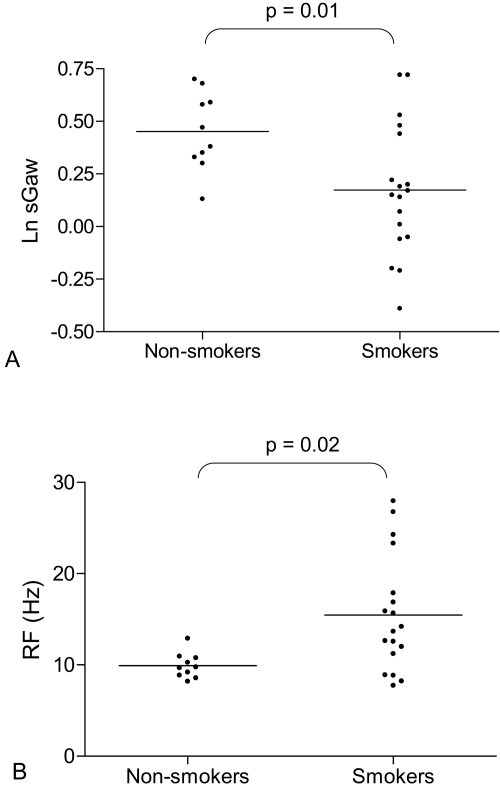

As a group, smokers had significantly lower MMEF and sGaw, and significantly higher RF compared to non-smokers (Figure 1, Table 1). FEV1/FVC was not quite significantly lower in smokers compared to non-smokers (p = 0.05) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Natural log (Ln) sGaw in non-smokers and smokers. Non-smokers (n = 10) and smokers (n = 18). Bars represent geometric means, t test used for comparison. (B) Resonant frequency (RF) in non-smokers and smokers. Non-smokers (n = 10) and smokers (n = 18). Bars represent means, t test used for comparison.

Table 1.

Pulmonary function, bronchial hyperreactivity, exhaled breath condensate and exhaled nitric oxide results in smokers and non-smokers

| Smokers (n = 18)d |

Non-smokers (n = 10) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (% predicted)a | 98.2 (8.5) | 104.7 (14.1) | 0.23 |

| FEV1/FVC (%)a | 76.2 (4.0) | 79.8 (5.2) | 0.05 |

| MMEF (% predicted)a | 64.1 (8.3) | 77.7 (14.1) | 0.003 |

| R5 (kPaL−1s)a | 0.39 (0.17) | 0.37 (0.07) | 0.63 |

| R20 (kPaL−1s)a | 0.31 (0.12) | 0.35 (0.07) | 0.34 |

| X5 (kPaL−1s)a | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.86 |

| RF (Hz)a | 15.5 (6.3) | 9.9 (1.38) | 0.02 |

| sGaw (kPaL−1s−1)b | 1.19 (1.36) | 1.57 (1.20) | 0.01 |

| Raw (kPaL−1s)a | 0.24 (0.08) | 0.19 (0.06) | 0.12 |

| TLC (% predicted)a | 106.1 (13.5) | 98.8 (4.9) | 0.11 |

| FRC (% predicted)a | 109.3 (29.8) | 103.3 (13.5) | 0.55 |

| RV (% predicted)a | 120.2 (36.6) | 104.5 (23.07) | 0.23 |

| PD20 (mg)b | 2.86 (5.09) | 8.15 (1.86) | 0.07 |

| FeNO at 50 ml/sec (ppb)b | 12.55 (5.62) | 15.71 (9.81) | 0.68 |

| CawNO (ppb)b | 58.88 (1.93) | 73.26 (2.30) | 0.45 |

| CalvNO (ppb)b | 3.56 (1.50) | 2.92 (1.63) | 0.26 |

| DawNO (pl/ppb/s)b | 7.40 (2.37) | 7.87 (2.37) | 0.85 |

| J’awNO (pl/s)b | 436.0 (2.5) | 576.4 (1.8) | 0.40 |

| EBC pHc | 7.16 (4.82–7.82) | 7.39 (7.29–7.75) | 0.18 |

| EBC 8-isoprostane (pg/ml)b | 49.9 (2.9) | 8.9 (4.0) | 0.001 |

| EBC LTB4 (pg/ml)b | 32.7 (3.1) | 23.0 (1.7) | 0.80 |

Mean (SD), t test.

Geometric mean (SD), t test.

Median (range), Mann-Whitney U test.

n = 18 except PD20 n = 15 and EBC pH n = 17.

CawNO (concentration of NO in the airway wall), CalvNO (alveolar concentration), DawNO (diffusing capacity of NO from the airway wall) and J’awNO (total maximal airway wall NO flux; the product of CawNO and DawNO).

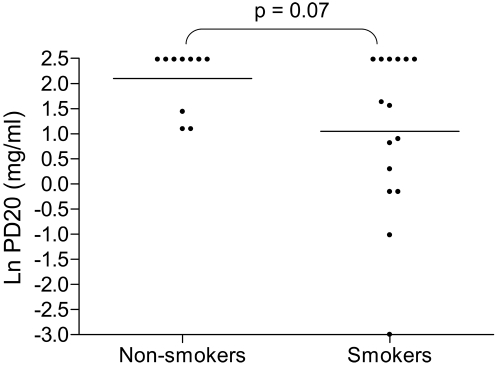

Methacholine challenge

A numerically higher proportion of smokers reacted to methacholine (ie, PD20 of 5.96 mg or less) compared to non-smokers (60% versus 30%) with a trend towards increased BHR in smokers that did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.07) (Figure 2, Table 1).

Figure 2.

Natural log (Ln) methacholine challenge PD20 in non-smokers and smokers. Non-smokers (n = 10) and smokers (n = 15). Bars represent geometric means, t test used for comparison.

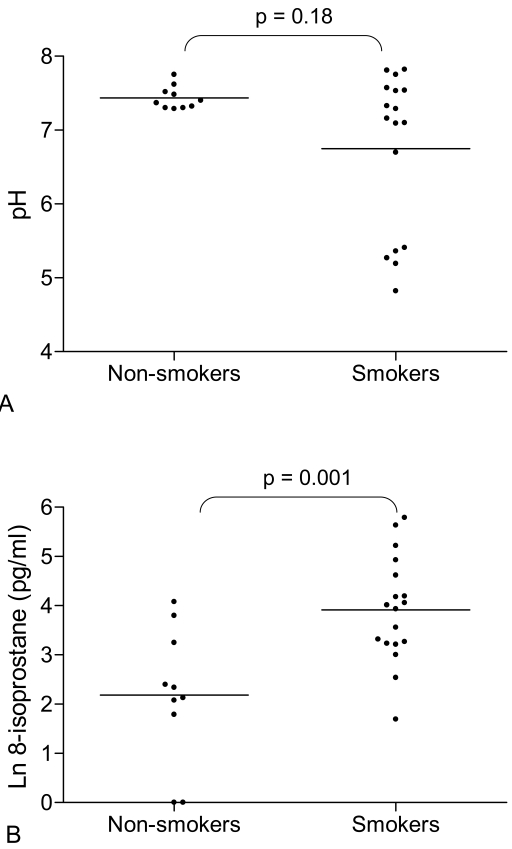

Exhaled breath condensate

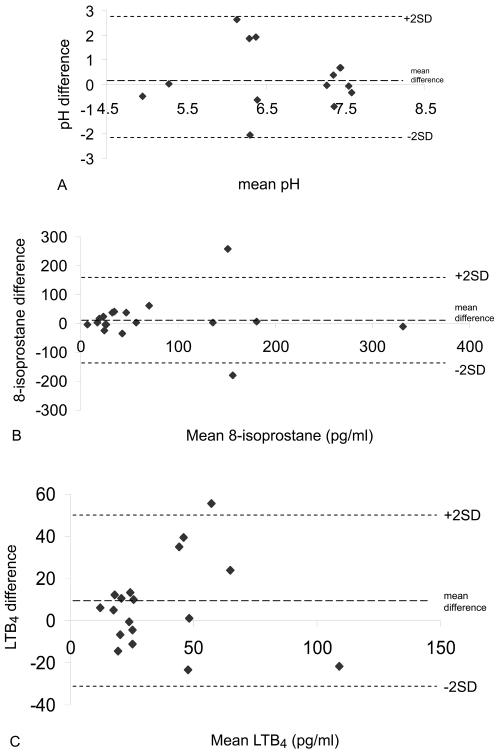

8-isoprostane was significantly higher in smokers compared to non-smokers (Figure 3A, Table 1). In contrast, levels of LTB4 did not differ between the 2 groups (Table 1). There was no statistical difference between the median values of EBC pH in smokers and non-smokers (Figure 3B, Table 1). However, there was evidence of airway acidification in some smokers; 5 smokers had very acidic EBC pH (less than 6). In contrast, the pH values in all non-smokers were greater than 7.2. While the within subject mean differences in EBC biomarkers was small and statistically insignificant (p > 0.05 for all comparisons), Bland Altman analysis revealed wide limits of agreement indicating marked between day variability in some individuals (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

(A) Natural log (Ln) exhaled breath condensate 8-isoprostane concentration in non-smokers and smokers. Non-smokers (n = 10) and smokers (n = 18). Bars indicate geometric mean values, t test used for comparison. (B) Exhaled breath condensate pH in non-smokers and smokers. Non-smokers (n = 10) and smokers (n = 17). Bars indicate median values, Mann-Whitney U test used for comparison.

Figure 4.

(A) Bland Altman plot of EBC pH reproducibility between visit 1 and visit 2 (n = 14). (B) Bland Altman plot of EBC 8-isoprostane reproducibility between visit 1 and visit 2 (n = 18). (C) Bland Altman plot of EBC LTB4 reproducibility between visit 1 and visit 2 (n = 18).

Exhaled NO

FeNO at 50 ml/s and non-linear model derived parameters using multiple flow rates did not differ between the 2 groups (Table 1). Similarly, data derived using two other NO models did not differ between smokers and non-smokers (data not shown).

Induced sputum

The predominant cell type in smokers was neutrophils. Mean (SD) percentage neutrophil and macrophage count were 68.5% (18.8) and 30.4% (18.8) respectively. Geometric mean percentage eosinophil count and lymphocyte count (SD) were 0.51 (2.54), and 0.35 (2.31) respectively. Geometric mean (SD) total cell, neutrophil and macrophage count per gram of selected sputum were 1.2 (2.6) × 106, 0.8 (3.1) × 106 and 0.3 (2.6) × 106 respectively. Mean (SD) supernatant IL-8 concentration was 322.5 (154.7) pg/ml.

Correlations between non-invasive inflammatory markers in smokers

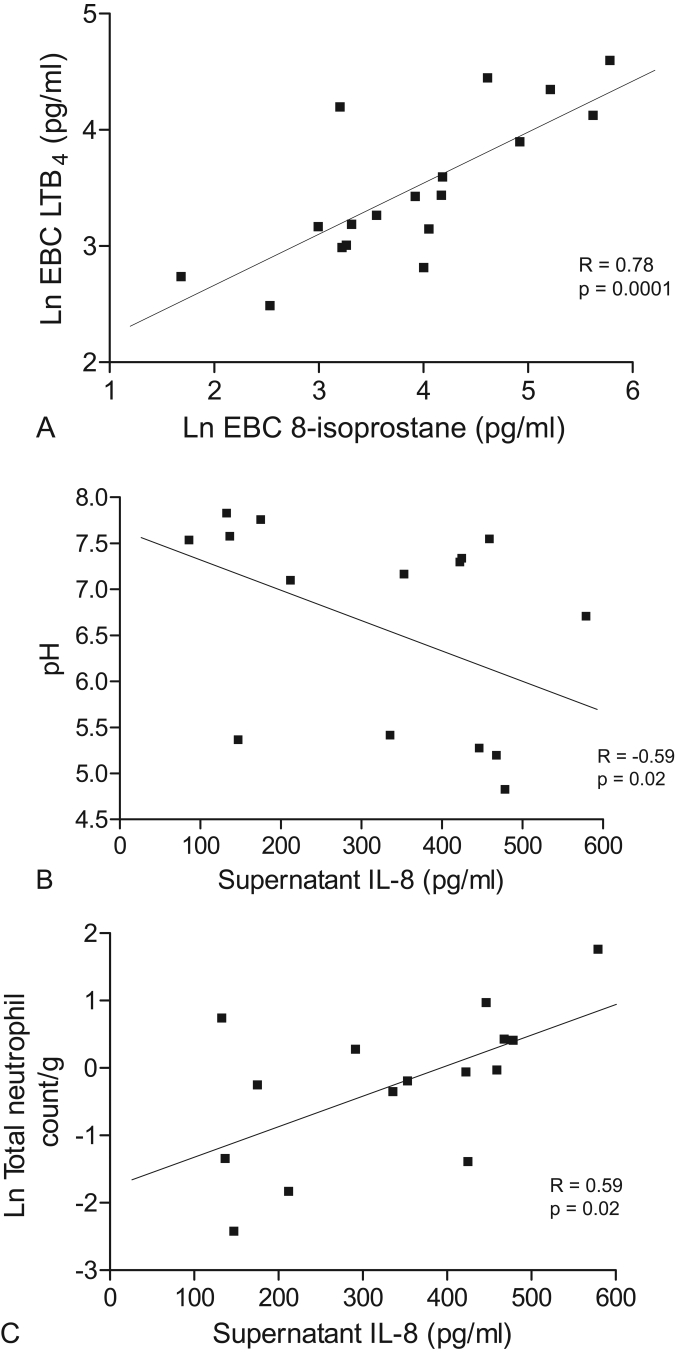

There was a significant correlation between EBC 8-isoprostane and LTB4 (r = 0.78, p < 0.0001) in smokers (Figure 5a, Table 2). However, 8-isoprostane and LTB4 did not correlate with sputum neutrophilia or with any other measurements (p > 0.05 for all comparisons, Table 2). Sputum supernatant IL-8 correlated significantly with EBC pH (r = −0.59, p = 0.02 Figure 5b, Table 2), total neutrophil count per gram of sputum (r = 0.59, p = 0.02, Figure 5c, Table 2) and total cell count per gram of sputum (0.54, p = 0.04, Table 2). Exhaled NO (including model derived parameters) showed no significant correlations with the other measurements (p > 0.05 for all comparisons, data not shown).

Figure 5.

(A) Pearson’s correlation in smokers between natural log (Ln) exhaled breath condensate 8-isoprostane and LTB4 (n = 18). (B) Spearman’s correlation in smokers between sputum supernatant IL-8 (pg/ml) and EBC pH (n = 15). (C) Pearson’s correlation in smokers between sputum supernatant IL-8 (pg/ml) and natural log (Ln) sputum total neutrophil count (n = 15).

Table 2.

Correlations between non-invasive biomarkers. Data are Spearman’s correlations for EBC pH data and Pearson’s correlations for all other data

| Ln EBC 8-isoprostane |

Ln EBC LTB4 | Supernatant IL-8 (pg/ml) |

Ln TCC/g | Ln Total neutrophil count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | n = 17 | n = 17 | n = 15 | n = 14 | n = 14 |

| R = −0.07 | R = 0.32 | R = −0.59 | R = −0.18 | R = −0.17 | |

| p = 0.79 | p = 0.21 | p = 0.02 | p = 0.54 | p = 0.56 | |

| Ln EBC | n = 18 | n = 16 | n = 15 | n = 15 | |

| 8-isoprostane | R = 0.78 | R = 0.33 | R = 0.45 | R = 0.39 | |

| p = 0.0001 | p = 0.21 | p = 0.09 | p = 0.16 | ||

| Ln EBC | n = 16 | n = 15 | n = 15 | ||

| LTB4 | R = 0.19 | R = 0.30 | R = 0.25 | ||

| p = 0.47 | p = 0.28 | p = 0.38 | |||

| Supernatant | n = 15 | n = 15 | |||

| IL-8 (pg/ml) | R = 0.54 | R = 0.59 | |||

| p = 0.04 | p = 0.02 |

Discussion

The major findings of this study were that the sensitive techniques of plethysmography and IOS showed the detrimental effects of smoking even while FEV1 was normal, and that smokers had raised EBC 8-isoprostane and sputum neutrophilia, while a proportion had acidified airway pH. Reduced EBC pH has been reported in established COPD (Kostikas et al 2002) but this is the first study to demonstrate acidification of EBC in smokers without COPD. The significant association between sputum IL-8 and EBC pH is suggestive of links between airway acidity and airway inflammation in smokers. We also observed considerable variability in EBC measurements. These key findings are now discussed in more detail.

Comparison of smokers and non-smokers

Smokers with normal lung function are known to have increased mucosal inflammation, mucus hypersecretion and pathological changes typical of early emphysema (Clark et al 2001; Saetta et al 2001). The current study suggests that these pathological abnormalities lead to reduced MMEF, reduced sGaw and increased RF. The spirometric abnormalities observed in the current study have been previously reported (Clark et al 2001; D’Ippolito et al 2001). To our knowledge, this is the first study to also use body plethysmography and IOS. There is published oscillometry evidence (using a forced random noise generator) that smokers have abnormal RF20 (Hayes et al 1979). Abnormalities of MMEF and RF may be due to peripheral airway dysfunction (Cosio et al 1978; Bouaziz et al 1996; Kaczka et al 1999). We also observed reduced sGaw in smokers, indicating that the decreased airway conductance found in COPD patients (Mitchell et al 1967) is also present in smokers. Overall, these findings demonstrate that in smokers with normal FEV1 there is small airway dysfunction, decreased airway conductance and reduced lung compliance.

A numerically higher number of smokers had methacholine hyperreactivity compared to non-smokers, although there was no difference between the group PD20 mean values. This may have been due to insufficient sample size. Nevertheless, our results show that bronchial hyperreactivity is present is some smokers, and previous data indicates that these subjects may be at increased risk of COPD (Tashkin et al 1996).

Acidified EBC pH has been reported in established COPD (Kostikas et al 2002) but there are no reports of EBC pH in smokers without COPD. We found that several smokers had very acidic EBC pH (< 6), a phenomenon observed in COPD but not in non-smokers (Borrill et al 2005, 2006). Although the median pH values of smokers and non-smokers were not statistically different, it is clear that a subgroup of smokers have acidic airway pH. The reasons for this finding are unclear. It has previously been reported that airway acidification is related to bacterial colonisation in bronchiectasis and to neutrophilic inflammation and oxidative stress in COPD (Kostikas et al 2002). This study provides supporting evidence to suggest a link between neutrophilic inflammation and airway acidity, demonstrating a correlation between sputum supernatant IL-8 and EBC pH. Cigarette smoke contains substances capable of causing oxidative stress and cellular toxicity (McNee and Rahman 2001). These properties alter airway cell function, increasing levels of airway inflammation in smokers. Such altered cell function may also lead to airway acidification, either due to increased acid production, or decreased buffering capacity. Further work is needed to elucidate the reasons for and importance of airway acidification in smokers.

We observed increased levels of the oxidative stress biomarker EBC 8-isoprostane in smokers compared to non-smokers in agreement with a previous report (Montuschi et al 2000). This was demonstrated despite the recent observation that use of the EcoScreen results in lower levels of 8-isoprostane than other condenser coatings (Rosias et al 2006). However, we found no difference in EBC LTB4 between smokers and controls. This is in contrast to a previous study using the same immunoassay method; while LTB4 levels were higher in smokers compared to non-smokers, it should be noted that the levels reported were much lower compared to the current study (Montuschi et al 2003). Furthermore, recent work has suggested that LTB4 present in EBC is mainly due to salivary contamination (Gaber et al 2006). Analysis of inflammatory markers in EBC has not been standardized, and reported levels of LTB4 and 8-isoprostane vary (Montuschi et al 2000; Kostikas et al 2003; Montushci et al 2003; van Hoydonck et al 2004). Alternative methods such as mass spectrometry may improve variability and sensitivity (Cap et al 2004; Montuschi et al 2004).

Previous studies have shown reduced FeNO in smokers compared to non-smokers (Kharitonov et al 1995; Corradi et al 1999; Rytila et al 2006), probably through inhibition of nitric oxide synthase activity (Hoyt et al 2003). However, increased numbers of inducible nitric oxide synthase positive cells have also been observed in sputum from smokers compared to non-smokers (Rytila et al 2006). In the current study there was no difference in FeNO between smokers and non-smokers, and no reduction in the bronchial wall concentration of NO in smokers in contrast to previous studies (Hogman et al 2002; Malinovschi et al 2006). Levels of exhaled NO in smokers are determined by the balance between inhibition of nitric oxide synthase activity caused by smoking and upregulation of this enzyme caused by inflammation, as well as NO consumption which may be affected by a variety of factors including the levels of reactive oxygen species (Ichinose et al 2000) and the degree of bacterial colonization (Gaston et al 2002). We speculate that the smokers in the current study had levels of airway inflammation that counter-balanced the inhibitory effect of smoking on exhaled NO levels.

We were unable to obtain induced sputum specimens from the majority of healthy non-smokers in this study. However, it is known that macrophages are the predominant cell type in induced sputum from healthy non-smokers (Belda et al 2000). In contrast, smokers in this study had predominant neutrophilia. Pizzichini et al showed a trend towards increased neutrophilia in smokers with non-obstructive chronic bronchitis and predominant neutrophilia in established COPD (Pizzichini et al 1996). Studies have also observed increased neutrophilia in smokers with normal FEV1 compared to non-smokers (Chalmers et al 2001; Rytila et al 2006). Neutrophils play a key role in innate immunity, and it is clear that an abnormal innate immune response is present in the airways of smokers with and without COPD.

Reproducibility of EBC biomarkers in smokers

We assessed the reproducibility of EBC biomarkers using the Bland-Altman method, which calculates the limits of agreement (ie, the range of variation that can be expected for repeated measurements from the same subject) (Bland and Altman 1986). This is the first report of the variability of EBC pH, 8-isoprostane and LTB4 in smokers. Overall, our results for all measurements demonstrated only small changes in group mean differences over 1 week. However, the variability between individual measurements (determined by the limits of agreement) may be relatively large. Using limits of agreement, we have recently shown considerable within subject variability of EBC 8 isoprostane and LTB4 in COPD patients (Borrill et al 2007) and of EBC pH from COPD patients compared to healthy controls (Borrill et al 2005). We believe that this increased variability compared to that observed in healthy subjects is due to greater changes in airway inflammation over time in COPD patients. Similarly, the results in the current study suggest that these changes in airway inflammation over time also occur in smokers.

Although the current study used a relatively small sample size, we were still able to adequately assess the reproducibility of the EBC biomarkers. For 8-isoprostane and LTB4, the poor reproducibility contributes to the reduced sensitivity of these measurements in small sample sizes. However, despite these issues, this study still provides some novel insights into the effects of smoking on the airways.

Correlations in smokers

There was a strong correlation between exhaled breath condensate LTB4 and 8-isoprostane in smokers. However, there were no significant correlations between these 2 biomarkers and EBC pH. Similarly, it has been shown in COPD patients that EBC pH and 8-isoprostane are not related (Kostikas et al 2003). While pH did not relate to other EBC measurements, there was a significant correlation between EBC pH and sputum supernatant IL-8, a potent neutrophil chemoattractant. This suggests that airway acidification is related to neutrophilic influx in smokers. Indeed in COPD patients a similar relationship was observed between EBC pH and sputum neutrophilia (Kostikas et al 2002), although in our study this relationship failed to reach statistical significance. Our observation of a significant correlation between sputum supernatant IL-8 and both total cell count and total neutrophil count are in agreement with a previous study (Chalmers et al 2001).

Conclusion

The pathological processes of airway inflammation and oxidative stress were demonstrated in smokers using non-invasive biomarkers. The positive relationship observed between sputum IL-8 and EBC pH suggests that airway acidity is related to neutrophilic inflammation. Therefore, these techniques may be useful in the early detection of cigarette smoke-induced pathophysiological abnormalities. However, our EBC reproducibility data adds to the growing body of evidence indicating that the sensitivity and reproducibility of 8 isoprostane and LTB4 assays need to be improved.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Andrew Hazel with the exhaled nitric oxide models.

Funding source This study was funded by a grant from Glaxo Smith Kline. The study sponsors (via the listed author) were involved in the study design, data analysis and interpretation, writing the report and the decision to submit the paper for publication. They had no role in the collection of data from subjects.

Footnotes

Competing interests No financial or other potential conflicts of interest exist with regard to this study for any of the contributing authors.

References

- American Thoracic Society. Recommendations for standardised procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:2104–17. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.ats8-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belda J, Leigh R, Parameswaran K, et al. Induced sputum cell counts in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:475–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9903097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between 2 methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrill Z, Starkey C, Vestbo J, et al. Reproducibility of exhaled breath condensate pH in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:269–74. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00085804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrill ZL, Smith JA, Naylor J, et al. The effect of gas standardisation on exhaled breath condensate pH. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:251–2. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00026706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrill ZL, Starkey RC, Singh SD. Variability of exhaled breath condensate leukotriene B4 and 8-isoprostane in COPD patients. Int J COPD. 2007 doi: 10.2147/copd.2007.2.1.71. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz N, Beyaert C, Gauthier R, et al. Respiratory system reactance as an indicator of the intrathoracic airway response to methacholine in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996;22:7–13. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199607)22:1<7::AID-PPUL2>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cap P, Chladek J, Pehal F, et al. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis of exhaled leukotrienes in asthmatic patients. Thorax. 2004;59:465–70. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.011866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpagnano GE, Kharitonov SA, Foschino-Barbaro MP, et al. Increased inflammatory markers in the exhaled breath condensate of cigarette smokers. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:589–93. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00022203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers GW, MacLeod KJ, Thomson L, et al. Smoking and airway inflammation in patients with mild asthma. Chest. 2001;120:1917–22. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KD, Wardrobe-Wong N, Elliott JJ, et al. Patterns of lung disease in a normal smoking population. Are emphysema and airflow obstruction found together? Chest. 2001;120:743–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.3.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradi M, Majori M, Cacciani GC, et al. Increased nitric oxide in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54:572–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosio M, Ghezzo H, Hogg JC, et al. The relations between structural changes in small airways and pulmonary-function tests. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:1277–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197806082982303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ippolito R, Foresi A, Chatta A, et al. Eosinophils in induced sputum from asymptomatic smokers with normal lung function. Respir Med. 2001;95:969–74. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaber F, Acevedo F, Delin I, et al. Saliva is one likely source of leukotriene B4 in exhaled breath condensate. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:1229–35. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00151905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston B, Ratjen F, Vaughan JW, et al. Nitrogen redox balance in the cystic fibrosis airway: effects of antipseudomonal therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:387–90. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.3.2106006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes DA, Pimmel RL, Fullton JM, et al. Detection of respiratory mechanical dysfunction by forced random noise impedence parameters. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:1095–9. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.5.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogman M, Holmkvist T, Wegener T, et al. Extended NO analysis applied to patients with COPD, allergic asthma and allergic rhinitis. Respir Med. 2002;96:24–30. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath I, Hunt J, Barnes PJ, et al. Exhaled breath condensate: methodological recommendations and unresolved questions. Eur Respir J. 2006;26:523–48. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00029705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt JC, Robbins RA, Habib M, et al. Cigarette smoke decreases inducible nitric oxide synthase in lung epithelial cells. Exp Lung Res. 2003;29:17–28. doi: 10.1080/01902140303759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose M, Sugiura H, Yamagata S, et al. Increase in reactive nitrogen species production in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:701–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9908132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczka DW, Ingenito EP, Israel E, et al. Airway and lung tissue mechanics in asthma. Effects of albuterol. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:169–78. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9709109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonov SA, Robbins RA, Yates D, et al. Acute and chronic effects of cigarette smoking on exhaled nitric oxide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:609–12. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7543345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostikas K, Papatheodorou G, Ganas K, et al. pH in expired breath condensate of patients with inflammatory airways diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1364–70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200111-068OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostikas K, Papatheodorou G, Psathakis K, et al. Oxidative stress in expired breath condensate in patients with COPD. Chest. 2003;124:1373–80. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley SJ, Holden J, Derham A, et al. Fluticasone Propionate via the Diskhaler or Hydrofluoroalkane-134a metered-dose inhaler on methacholine-induced airway hyperesponsiveness. Chest. 2002;122:806–11. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.3.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinovschi A, Janson C, Holmkvist T, et al. Effect of smoking on exhaled nitric oxide and flow-independent nitric oxide exchange parameters. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:339–45. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00113705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNee W, Rahman I. Is oxidative stress central to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)01912-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M, Watanabe S, Renzetti AD. Evaluation of airway conductance measurements in normal subjects and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967;96:685–91. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.96.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montuschi P, Collins J, Ciabattoni G, et al. Exhaled 8-isoprostane as an in vivo biomarker of lung oxidative stress in patients with COPD and healthy smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1175–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.2001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montuschi P, Kharitonov SA, Ciabattoni G, et al. Exhaled leukotrienes and prostaglandins in COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:585–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.7.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montuschi P, Martello S, Felli M, et al. Ion trap liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry analysis of leukotriene B4 in exhaled breath condensate. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:2723–9. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietropaoli AP, Perillo IB, Torres A, et al. Similtaneous measurement of nitric oxide production by conducting and alveolar airways of humans. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1532–42. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.4.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzichini E, Pizzichini MMM, Efthimiadis A, et al. Indices of airway inflammation in induced sputum: reproducibility and validity of cell and fluid-phase measurements. Am J Rspir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:308–17. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman I. Reproducibility of oxidative stress biomarkers in breath condensate: are they reliable? Eur Resp J. 2004;23:183–4. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00131604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosias PP, Robroeks CM, Niemarkt HJ, et al. Breath condenser coatings affect measurement of biomarkers in exhaled breath condensate. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:1036–41. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00110305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytila P, Rehn T, Ilumets H, et al. Increased oxidative stress in asymptomatic current chronic smokers and GOLD stage 0 COPD. Respir Res. 2006;7:69. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saetta M, Turato G, Maestrelli P, et al. Cellular and structural bases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1304–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.2009116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silkoff PE, Sylvester JT, Zamel N, et al. Airway nitric oxide diffusion in asthma. Role in pulmonary function and bronchial responsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1218–28. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9903111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanescu D, Sanna A, Veriter C, et al. Identification of smokers susceptible to development of chronic airflow limitation. A 13-year follow-up. Chest. 1998;114:416–25. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin DP, Altose MD, Connett JE, et al. Methacholine reactivity predicts changes in lung function over time in smokers with early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1802–11. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoydonck PGA, Wuyts WA, Vanaudenaerde BM, et al. Quantitative analysis of 8-isoprostane and hydrogen peroxide in exhaled breath condensate. Eur Respir J 2004. 2004;23:189–92. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00049403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]