Abstract

Background

Improvements in ventilatory mechanics with tiotropium increases exercise tolerance during pulmonary rehabilitation. We wondered whether tiotropium also increased physical activities outside of pulmonary rehabilitation.

Methods

COPD patients participating in 8 weeks of pulmonary rehabilitation were studied in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tiotropium 18 μg daily (tiotropium = 47, placebo = 44). Study drug was administered for 5 weeks prior to, 8 weeks during, and 12 weeks following pulmonary rehabilitation. Patients completed a questionnaire documenting participation in pre-defined activities outside of pulmonary rehabilitation during the 2 weeks prior to each visit. Patients who submitted an activity questionnaire at week 4 and on at least one subsequent visit were included in the analysis. For each patient, the number of sessions was multiplied with the duration of each activity and then summed to give overall activity duration.

Results

Patients (n = 46) had mean age of 67 years, mean baseline FEV1 of 0.84 L (33% predicted). Mean (SE) increase in duration of activities (minutes during 2 weeks prior to each visit) from week 4 (prior to PR) to week 13 (end of PR) was 145 (84) minutes with tiotropium and 66 (96) minutes with placebo. The increase from week 4 to week 25 (end of follow-up) was 262 (96) and 60 (93) minutes for the respective groups. Increases in activity duration from week 4 to weeks 17, 21, and 25 were statistically significant with tiotropium. No statistical differences over time were observed within the placebo-treated group and differences between groups were not significant.

Conclusions

Tiotropium appears to amplify the effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation as seen by increases in patient self-reported participation in physical activities.

Keywords: activity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, exercise, pulmonary rehabilitation, tiotropium

Background

In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), physiological impairments imposed by the progressive nature of the disease, including airflow limitation and hyperinflation lead to reduced exercise tolerance. Reduced exercise tolerance in turn leads to self-imposed activity limitation which then leads to deconditioning (ACCP/AACVPR 1997; GOLD 2005). Regular exercise training programs, such as those administered through pulmonary rehabilitation programs, consistently improve exercise endurance in patients with COPD (GOLD 2005). GOLD guidelines for COPD recommend exercise training for COPD patients with disease severity of GOLD stage II to IV (GOLD 2005). Presumably, improving ventilatory mechanics can lead to an increased ability to train and augment the benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation.

Tiotropium 18 μg given once daily has been shown to provide sustained 24-hour improvements in airflow (Casaburi et al 2002), reduce hyperinflation (Celli et al 2003; O’Donnell et al 2004a; Maltais et al 2005), and improve endurance time during constant work exercise (O’Donnell et al 2004a; Maltais et al 2005) due to prolonged muscarinic M3-receptor antagonism. We previously reported that tiotropium, in combination with pulmonary rehabilitation, improved ventilatory mechanics and augmented the exercise tolerance benefits of rehabilitation compared with a control group receiving rehabilitation training without tiotropium (Casaburi et al 2005).

As part of the protocol of this study, a simple questionnaire allowed the patients to track their participation in physical activities outside of the pulmonary rehabilitation program. In the current analysis, we retrospectively evaluated a group of patients completing an activities questionnaire to determine whether patients who participated in a clinical trial of exercise training with a combination of treatment with tiotropium and pulmonary rehabilitation were able to increase their physical activity outside of the pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Methods

Study design

A 25-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in patients with COPD to determine the efficacy of tiotropium compared with placebo on exercise tolerance in patients participating in a pulmonary rehabilitation program (previously reported) (Casaburi et al 2005). The pulmonary rehabilitation training program was an 8-week program consisting of treadmill training 3 times per week for at least 30 minutes each session. Patients were randomized to receive either tiotropium 18 μg once daily or placebo for 5 weeks prior to, 8 weeks during, and 12 weeks following pulmonary rehabilitation. Patients used a questionnaire to record activities they performed outside of the pulmonary rehabilitation sessions.

A retrospective analysis was performed on the subgroup of patients completing an activities questionnaire at week 4 and on at least one other visit to determine whether patients were also able to increase their physical activity outside of pulmonary rehabilitation. This subgroup was also evaluated for improvements in exercise tolerance, lung function, dyspnea, and quality of life. Week 4 (prior to pulmonary rehabilitation) was designated as the baseline. Changes in exercise participation were calculated from this timepoint because changes in exercise participation would not be expected without the benefit of a pulmonary rehabilitation program in this population of severe and very severe COPD patients.

Participants

Patients included in the trial had a clinical diagnosis of COPD (Celli et al 2004), were at least 40 years of age, had a smoking history ≥10 pack-years, an FEV1 ≤60% predicted (Morris et al 1988), and an FEV1/FVC ratio ≤70%. Patients were required to be candidates for pulmonary rehabilitation and to meet the rehabilitation program inclusion criteria. Patients were excluded if there was a history of asthma, moderate to severe renal impairment, moderate to severe symptomatic prostatic hypertrophy, bladder-neck obstruction, narrow angle glaucoma, regular use of daytime oxygen, history of lung resection, or recent myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, or hospitalization for heart failure. Patients were also excluded if they had a history of orthopedic, muscular or neurologic disease that would interfere with regular participation in aerobic exercise or exercise testing, or if they had participated in pulmonary or cardiac rehabilitation in the preceding year.

Concomitant use of prn albuterol metered dose inhaler (100 μg/puff) was allowed throughout the study period. Concomitant use of theophylline preparations (excluding 24-hour preparations), inhaled corticosteroids, and modest doses of oral corticosteroids was allowed. Oral β-agonists, long-acting β-agonists, short-acting anticholinergics and other investigational drugs were not allowed during the study. The protocol is consistent with the ethical standards of Helsinki. All patients provided written, informed consent and the study was approved by local institutional review boards.

Study protocol

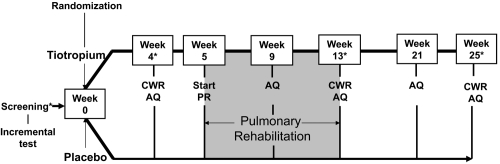

The study protocol is outlined in Figure 1. An incremental treadmill test was performed at the screening visit prior to randomization. At the following visit, patients were randomized to receive either tiotropium 18 μg once daily (Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH and Co. KG, Ingelheim, Germany) or placebo via a dry powder inhalation device (HandiHaler®, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH and Co. KG, Ingelheim, Germany) for the subsequent 25 weeks. After 4 weeks of treatment, constant work rate treadmill exercise testing (zero incline) at 80% of the peak speed achieved in an incremental treadmill test was used to measure endurance time prior to the start of pulmonary rehabilitation. Constant work rate treadmill exercise testing was repeated at the end of pulmonary rehabilitation, and 12 weeks after pulmonary rehabilitation had ended. At the screening visit and at weeks 4, 13, and 25, spirometry was used to determine morning pre-dose (trough) and post-dose forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). Dyspnea was assessed using the baseline (BDI) and transition dyspnea index (TDI) and health-related quality of life was assessed using the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (Mahler et al 1984; Jones et al 1992).

Figure 1.

Study design of 25-week randomized, controlled trial of tiotropium in COPD patients receiving pulmonary rehabilitation.

Abbreviations: CWR, constant work exercise; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation; AQ, activity questionnaire.

Notes: *Spirometry, Baseline/Transitional dyspnea index, and St. George’s respiratory questionnaire also performed.

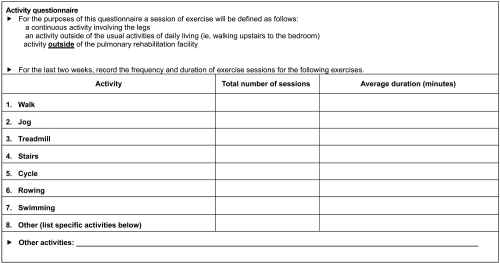

Activity questionnaire

At each clinic visit, patients were requested to complete an activity questionnaire (AQ) that was developed for this trial (Figure 2). This questionnaire captured participation in pre-defined activities during the 2 weeks prior to each visit. Data were included in the analysis from patients who submitted an AQ at week 4 and on at least one subsequent visit. For each patient, the number of sessions was multiplied by the duration for each activity and then summed to give overall activity duration.

Figure 2.

Contents of activity questionnaire administered to COPD patients participating in the trial.

Statistical analysis

The sample size of the study was initially powered based on expected differences in exercise duration and not for other outcomes such as the AQ. Differences in calculated activity duration from week 4 to subsequent visits were compared within treatment groups using paired t-tests. Other patient outcomes such as FEV1, exercise endurance time, TDI and SGRQ were analyzed specifically in the subgroup of patients who completed the questionnaire. These data are presented as adjusted means and standard error based on an analysis of covariance model with treatment and center as factors and the baseline value as covariate. P values were calculated for descriptive purposes only. Nominal statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05. The analysis was not corrected for multiple comparisons. (SAS/Stat software program, version 8.2, SAS, Cary, NC, USA)

Results

Results reported here are for the subgroup completing the AQ at week 4 (beginning of rehabilitation) and on at least one other subsequent visit.

Participants

Of 108 patients randomized to treatment (55 tiotropium; 53 placebo), 91 had data available for efficacy analysis for exercise endurance (47 tiotropium, 44 placebo), and 46 completed the AQ at week 4 and on at least one other visit (25 tiotropium, 21 placebo) The characteristics of the AQ subgroup were similar to those of the full cohort (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics of the full cohort (n = 108) and for the activity questionnaire (AQ) subgroup (n = 46)

| Full cohort |

AQ subgroup |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiotropium | Placebo | Tiotropium | Placebo | |

| Total randomized (n) | 55 | 53 | 25 | 21 |

| Males (%) | 55 | 59 | 56 | 52 |

| Age (years)a | 65.9 (8.8) | 67.3 (6.9) | 67.6 (7.2) | 67.2 (7.4) |

| Duration of COPD (years)a | 9.7 (7.6) | 8.9 (6.6) | 9.8 (8.0) | 7.1 (4.4) |

| Smoking history (pack-years)a | 58.6 (34.6) | 58.8 (31.4) | 57.9 (32.5) | 50.2 (24.3) |

| Current smoker (%) | 29.1 | 18.9 | 20.0 | 23.8 |

| BMI (kg/cm2)a | 25.0 (4.6) | 26.8 (5.6) | 24.4 (5.4) | 26.2 (5.9) |

| FEV1 (L)a | 0.82 (0.31) | 0.94 (0.40) | 0.78 (0.28) | 0.91 (0.45) |

| FEV1 (% predicted)a | 32.6 (12.4) | 36.2 (12.2) | 31.5 (12.3) | 35.8 (12.4) |

| FVC (L)a | 2.01 (0.68) | 2.14 (0.85) | 1.91 (0.62) | 1.99 (0.87) |

| FEV1/FVC (%)a | 41.5 (10.4) | 44.6 (11.2) | 41.6 (10.6) | 46.0 (11.4) |

| Incremental treadmill test | ||||

| Maximum speed (mph)a | 2.98 (0.87) | 2.81 (0.98) | 3.13 (0.92) | 2.90 (0.98) |

| Endurance time (min)a | 8.96 (2.84) | 8.83 (3.60) | 9.16 (3.02) | 7.91 (2.34) |

| BDI focal scorea | 5.7 (2.1) | 5.7 (1.9) | 5.9 (2.2) | 5.9 (1.8) |

| SGRQ total scorea | 50.4 (15.4) | 46.6 (16.1) | 48.8 (16.2) | 47.6 (18.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced respiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; BDI, baseline dyspnea index; SGRQ, St. George’s respiratory questionnaire.

Note: *Mean (SD).

Table 2.

Respiratory medications (proportion of population) used at any time during the trial period according to treatment group for the full cohort (n = 108) and the activity questionnaire (AQ) subgroup (n = 46)

| Respiratory medication (%) | Full cohort |

AQ subgroup |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiotropium n = 55 | Placebo n = 53 | Tiotropium n = 25 | Placebo n = 21 | |

| Anticholinergic | 9 | 4 | 12 | 0 |

| Long-acting beta-agonist | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Inhaled steroid | 46 | 32 | 56 | 29 |

| Theophylline | 18 | 21 | 20 | 14 |

| Oral steroid | 20 | 28 | 28 | 38 |

| Oxygen | 9 | 28 | 12 | 19 |

Activities in addition to pulmonary rehabilitation

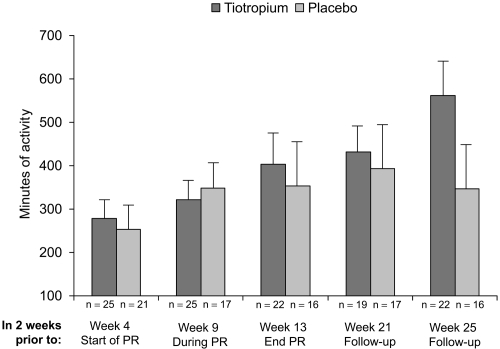

In the AQ subgroup, patients treated with tiotropium had a higher mean duration of participation in activities (in addition to pulmonary rehabilitation) during the 2 weeks prior to visits at weeks 4, 13, 17, 21, and 25 compared with patients taking placebo (Figure 3). At week 0 (prior to trial randomization), the mean (SE) duration of activities was 328 (100) and 155 (46) minutes in the tiotropium and placebo groups, respectively. The differences between groups were minor at week 4 prior to pulmonary rehabilitation (279 vs 253 minutes, Figure 3). Differences between groups were not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Mean (SE) minutes of activity during 2 weeks prior to each visit as reported through the activity questionnaire. Although not significantly different by statistical analysis, patients receiving tiotropium reported approximately 216 minutes more physical activity as compared with patients receiving placebo at week 25.

Abbreviation: PR, pulmonary rehabilitation.

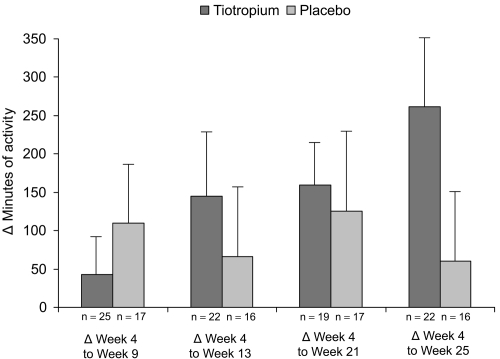

The improvements in duration of activities from week 4 (prior to rehabilitation) to subsequent visits were greater with tiotropium compared with placebo following pulmonary rehabilitation (week 13) and persisted during 12 weeks of follow-up (weeks 21 and 25) (Figure 4). The increases in activity duration from week 4 to weeks 17, 21, and 25 were statistically significant in the tiotropium group (Table 3). No statistical differences over time were observed within the placebo treated group (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Mean (SE) difference in duration of activities from week 4 (prior to pulmonary rehabilitation) to subsequent visits as reported through the activity questionnaire. Patients receiving tiotropium reported on average 262 minutes more exercise at the end of the study whereas patients receiving placebo reported a gain of only 60 minutes.

Table 3.

Mean (SE) duration of patient reported participation in physical activities outside of the pulmonary rehabilitation program in the treatment groups

| Tiotropium |

Placebo* |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Time (min) | ΔWeek 4 (min) | p-value for ΔWeek 4 | n | Time (min) | ΔWeek 4 (min) | p-value for ΔWeek 4 | |

| Prior to PR (week 4) | 25 | 279 (41) | – | – | 21 | 253 (50) | – | – |

| During PR (week 9) | 25 | 322 (39) | 43 (53) | 0.425 | 17 | 349 (74) | 110 (85) | 0.212 |

| End of PR (week 13) | 22 | 403 (81) | 145 (84) | 0.098 | 16 | 353 (100) | 66 (96) | 0.506 |

| Follow-up (week 17) | 22 | 526 (75) | 269 (63) | <0.001 | 16 | 355 (102) | 99 (106) | 0.369 |

| Follow-up (week 21) | 19 | 432 (59) | 159 (58) | 0.013 | 17 | 394 (97) | 125 (108) | 0.266 |

| Follow-up (week 25) | 22 | 562 (86) | 262 (96) | 0.013 | 16 | 346 (95) | 60 (93) | 0.529 |

Abbreviations: PR, pulmonary rehabilitation.

Note: p > 0.05 for between group differences.

The duration of individual activities over the 2-week period prior to each visit increased with pulmonary rehabilitation in both the tiotropium and placebo groups; however, the summed duration for each activity was generally greater with tiotropium (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean (SE) duration of each activity in treatment groups

| Tiotropium |

Placebo |

Tiotropium |

Placebo |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Duration (minutes) | n | Duration (minutes) | n | Duration (minutes) | n | Duration (minutes) | ||

| Walk | Cycling | ||||||||

| Week 4 | 21 | 256 (42) | 18 | 191 (43) | Week 4 | 1 | 90 | 1 | 120 |

| Week 9 | 20 | 251 (39) | 14 | 239 (55) | Week 9 | 5 | 62 (10) | 2 | 27 (3) |

| Week 13 | 17 | 327 (99) | 14 | 267 (61) | Week 13 | 1 | 60 | 1 | 20 |

| Week 21 | 18 | 270 (65) | 15 | 303 (76) | Week 21 | 2 | 54 (6) | 1 | 30 |

| Week 25 | 19 | 381 (95) | 14 | 257 (49) | Week 25 | 4 | 219 (100) | 1 | 60 |

| Treadmill | Other | ||||||||

| Week 4 | 5 | 84 (50) | 2 | 34 (14) | Week 4 | 4 | 203 (75) | 6 | 247 (62) |

| Week 9 | 11 | 153 (31) | 4 | 108 (43) | Week 9 | 5 | 97 (47) | 7 | 276 (84) |

| Week 13 | 12 | 140 (17) | 2 | 210 (30) | Week 13 | 8 | 151 (25) | 5 | 274 (97) |

| Week 21 | 8 | 145 (57) | 6 | 98 (17) | Week 21 | 6 | 324 (77) | 5 | 267 (170) |

| Week 25 | 12 | 132 (34) | 4 | 51 (17) | Week 25 | 8 | 267 (52) | 4 | 363 (271) |

| Stairs | Swimming | ||||||||

| Week 4 | 3 | 59 (22) | 6 | 33 (27) | Week 4 | 2 | 50 (30) | 0 | – |

| Week 9 | 5 | 78 (29) | 3 | 55 (43) | Week 9 | 2 | 78 (48) | 0 | – |

| Week 13 | 6 | 60 (28) | 3 | 37 (32) | Rowing | ||||

| Week 21 | 5 | 26 (9) | 4 | 49 (25) | Week 25 | 0 | – | 1 | 60 |

| Week 25 | 5 | 103 (87) | 4 | 40 (15) | Jog | 0 | – | 0 | – |

Endurance time, spirometry, dyspnea, and quality of life

Previously reported results for the full cohort showed that tiotropium in combination with pulmonary rehabilitation led to greater improvements in endurance time, spirometry, dyspnea, and quality of life than rehabilitation alone (Casaburi et al 2005). These improvements were sustained for at least 3 months following pulmonary rehabilitation (Casaburi et al 2005). As with the preceding section, results reported here are for the subgroup completing the AQ at week 4 (beginning of rehabilitation) and on at least one other subsequent visit.

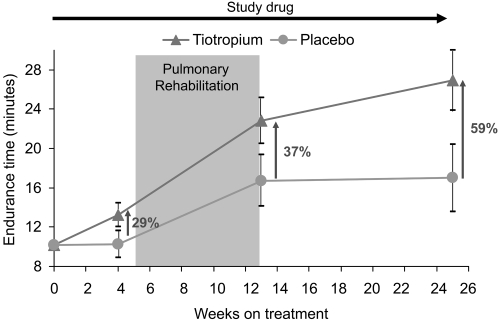

In the AQ subgroup, tiotropium provided numerically larger improvements in mean endurance time compared with placebo after 4 weeks of treatment (difference prior to pulmonary rehabilitation = 2.98 minutes), throughout the 8-week rehabilitation period (difference at end of pulmonary rehabilitation = 6.13 minutes) and up to 12 weeks following rehabilitation (difference at end of follow-up = 9.95 minutes) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Mean (SE) endurance times resulting from the combination of tiotropium and pulmonary rehabilitation in the subgroup of patients who completed the activity questionnaire. Patients receiving tiotropium continued to increase their measured exercise endurance during the 12-week period following pulmonary rehabilitation.

In the AQ subgroup, the difference in mean pre-dose (trough) FEV1 (tiotropium – placebo) was 0.07 L at the end of the 8-week rehabilitation period (Week 13) and 0.08 L at the end of the study (Week 25). Mean post-dose FEV1 was improved over placebo with tiotropium by 0.13 L at the end of the 8-week rehabilitation period (Week 13) and by 0.10 L at the end of the study (Week 25).

In the AQ subgroup, tiotropium improved the mean TDI Focal score over placebo by 1.36 units at the end of the 8-week rehabilitation period (2.80 units with tiotropium vs 1.45 units with placebo) and by 2.50 units at the end of the study (3.08 vs 0.58 units). Tiotropium improved the mean SGRQ Total score (a lower score indicates improvement) compared with placebo by 3.83 units at the end of the 8-week rehabilitation period (39.39 units with tiotropium vs 43.22 units with placebo) and by 5.64 units at the end of the study (39.06 units vs 44.70 units, respectively).

Discussion

Pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD has consistently been reported to improve exercise tolerance, dyspnea and health-related quality of life (ACCP/AACVPR 1997). Tiotropium 18 μg once daily increases exercise endurance and patient-reported outcomes through sustained 24-hour improvements in airflow and hyperinflation (Casaburi et al 2002; Celli et al 2003; O’Donnell et al 2004a; Maltais et al 2005). A recent study has demonstrated that tiotropium can augment the benefits observed in pulmonary rehabilitation programs (Casaburi et al 2005). As part of this study, a simple questionnaire was used to track patient participation in physical activities outside of the pulmonary rehabilitation program. Comparing the change from immediately prior to pulmonary rehabilitation to the conclusion of the pulmonary rehabilitation program, patients treated with tiotropium reported, on average, more than twice the number of minutes engaged in physical activities compared to the control group. Comparing the change from immediately prior to pulmonary rehabilitation to the end of the 12-week follow-up period, this increased to over 4 times the mean number of minutes compared to the control group at the end of the 12-week follow-up period. There was a pattern of larger improvements in the tiotropium group at all time points although the magnitude of improvement varied. The improvements in the tiotropium group were statistically significant whereas changes in the placebo group were not. None of the differences between groups (tiotropium – placebo) achieved statistical significance; however, the sample size was small and the instrument was considered an exploratory secondary endpoint in the study. The results of the questionnaire suggest that tiotropium was associated with increased participation in physical activities in patients with severe and very severe COPD who were enrolled in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

The standard outcome measures following interventions in COPD have included spirometry, lung volumes, dyspnea, exercise endurance, exacerbations and health status. Few studies have been devoted to objective examination of whether an intervention can lead patients to engage in increased physical activities. The primary reason is lack of tools that can document the outcome. Measures of patient perception of dyspnea, such as the transition dyspnea index, indicate that the patient is able to engage in activities with less breathlessness, or engage longer in activities, or take on more strenuous activities; however, the instrument does not document the degree or duration of participation in physical activities (Mahler et al 1984). Health status instruments such as the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire and the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire also do not document the degree or duration of participation (Guyatt et al 1987; Jones et al 1992). Exercise testing, such as incremental or constant work cycle ergometry, can indicate that patients are able to engage in activities for longer periods of time, provided the intervention is efficacious but these tests are laboratory based. The Pulmonary Function Status Questionnaire has sub-scores of daily activities, household tasks, meal preparation, and grocery shopping but this questionnaire does not indicate duration of participation (Weaver et al 1992). Therefore, a tool with the ability to objectively document home-based activity would be desirable to measure the effect of interventions in patients with COPD.

The present analysis supports previous information that interventions in COPD can result in improvements in the ability to participate in physical tasks. In a 6-week double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study, tiotropium resulted in a 21% improvement in endurance time during constant work cycle ergometry set at 75% of the maximum work rate of a preceding symptom limited incremental test (O’Donnell et al 2004a). These results were corroborated in a subsequent clinical trial using a similar design in which tiotropium improved constant work cycle ergometry duration by 69% vs 10% in the control group (Maltais et al 2005). In addition, improvements were observed in a second test on the same test day performed 8 hours post dose (Maltais et al 2005). Salmeterol has also demonstrated improvements in constant work cycle ergometry in a single-center crossover study, although improvements in exercise duration with long-acting β-agonists have not been consistently observed (Rennard et al 2001; Aalbers et al 2002; O’Donnell et al 2004b). Pulmonary rehabilitation, however, is the intervention that appears to produce the largest improvements in exercise training in COPD patients (ACCP/AACVPR 1997). For all of the aforementioned interventions, information is scarce regarding objective documentation of participation in physical activities in the patients’ home environment.

There are several limitations to the present report. The questionnaire was developed as a tracking instrument without standard psychometric development processes. For example, patient focus groups were not held to identify which activities are most important to rehabilitation patients. In addition, sufficient information from the questionnaire was obtained only in a subpopulation of patients as this was not considered a primary outcome. The results of the questionnaire cannot be generalized to a broader COPD population as the COPD patients eligible for pulmonary rehabilitation represent the severe end of the COPD spectrum. In addition, the sample size does not provide adequate power to determine statistical significance between the active treatment and the control groups. Nevertheless, patterns and trends in the results of the questionnaire support the benefits observed for other outcomes in both the full cohort as described by Casaburi et al (2005) and the subgroup having adequate activity questionnaire data in the present analysis. Furthermore, although the results suggest that improvements can be maintained following pulmonary rehabilitation, the follow-up period in the present study was limited to 12 weeks and further, longer term data is needed. Finally, it should also be recognized that the use of an accelerometer in studies of activity provide objective measures of movement and would be needed to validate activity-based questionnaires such as the one used in the present study.

Conclusions

In summary, a previously published clinical trial showed that tiotropium 18 μg once daily in addition to pulmonary rehabilitation leads to greater improvements in endurance time than rehabilitation alone in patients with COPD (Casaburi et al 2005). The results of an activity questionnaire in the reported study showed increases in patient self-reported participation in physical activities outside of pulmonary rehabilitation thereby supporting the observation that tiotropium amplifies the effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation. While this observation corroborates the significant improvements in treadmill endurance time with tiotropium relative to the control group documented in the pulmonary rehabilitation trial, definitive conclusions are limited as not all patients submitted the activity form. The simple, self-reported activity questionnaire described here can be used as a basis for development and testing of a more efficient and applicable tool to help track physical activities performed outside of pulmonary rehabilitation facilities.

Acknowledgments

We wish to gratefully acknowledge the statistical support of Inge Leimer and editorial support of Terry Keyser. Both Inge Leimer and Terry Keyser are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Footnotes

Disclosures Dr. Kesten is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Casaburi and Dr. Cooper have received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, serve on the Academic Advisory Board and are members of the Speakers’ Bureau of Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Casaburi is a consultant and serves on the Speakers’Bureau of Pfizer. This study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim and Pfizer.

References

- Aalbers R, Ayres J, Backer V, et al. Formoterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized, controlled, 3-month trial. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:936–43. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00240902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACCP/AACVPR Pulmonary Rehabilitation Guidelines Panel. ACCP/AACVPR Pulmonary Rehabilitation Guidelines. Chest. 1997;112:1363–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaburi R, Kukafka D, Cooper CB, et al. Improvement in exercise tolerance with the combination of tiotropium and pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;127:809–17. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaburi R, Mahler DA, Jones PW, et al. A long-term evaluation of once-daily inhaled tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:217–24.. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00269802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli BR, MacNee W ATS/ERS Task Force Committee Members. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli B, ZuWallack R, Wang S, et al. Improvements in resting inspiratory capacity and hyperinflation with tiotropium in COPD with increased static lung volumes. Chest. 2003;124:1743–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [GOLD] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. NHLBI/WHO Workshop Report [online] 2005 2001, Update 2005. Accessed November 10, 2005. URL: http://www.goldcopd.com.

- Guyatt GH, Berman LB, Townsend M, et al. A measure of quality of life for clinical trials in chronic lung disease. Thorax. 1987;42:773–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.10.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, et al. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1321–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler DA, Weinberg DH, Wells CK, et al. Baseline dyspnoea index and transitional dyspnoea index: The measurement of dyspnoea. Chest. 1984;85:751–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.85.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltais F, Hamilton A, Marciniuk D, et al. Improvements in symptom-limited exercise performance over eight hours with once-daily tiotropium in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128:1168–78. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF, Koski A, Temple WP, et al. Fifteen year interval spirometric evaluation of the Oregon predictive equations. Chest. 1988;93:123–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell D, Flüge T, Gerken F, et al. Effects of tiotropium on lung hyperinflation, dyspnoea and exercise tolerance in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004a;23:832–40. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00116004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell DE, Voduc N, Fitzpatrick M, et al. Effect of salmeterol on the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2004b;24:86–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00072703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennard SI, Anderson W, Zuwallack R, et al. Use of a long-acting inhaled β2-adrenergic agonist, salmeterol xinafoate, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1087–92. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.9903053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver TE, Narsavage GL. Physiological and psychological variables related to functional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nurs Res. 1992;41:286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]