Abstract

Objective: Despite the substantial distress and impairment often associated with skin picking, there currently is only limited research examining various phenomenological aspects of this behavior. The present research contributes to the existing literature by investigating phenomenological variables related to skin picking, such as family involvement, anxiety, depression, and the emotional consequences of skin picking. Moreover, on the basis of symptom severity level, differences were explored between individuals with skin picking who were from a psychiatric population.

Method: Forty individuals with various clinician-ascertained DSM-IV diagnoses in addition to skin picking symptomatology participated in the present study, which was conducted from September 2002 through January 2003. Participants were administered a self-report questionnaire (which assessed demographic, symptom, and past diagnostic information) as well as the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, and the Self-Injury Interview.

Results: Phenomenological data on various aspects of individuals with skin picking are presented. Individuals with mild skin picking and individuals with severe skin picking were compared and found to differ in the level of distress they experienced (t = −2.35, p = .05) and the amount of damage caused by their picking behavior (t = −3.06, p = .01).

Conclusion: Overall, skin picking represents a behavior with its own unique characteristics and accompanying levels of distress and impairment that warrants specific attention by clinicians.

Anonclinical populations, surprisingly, there is limted existing literature about the theoretical and phenomenological aspects of this behavior. In our clinical experience, as a behavior, skin picking can range greatly in its severity, level of interference, degree of pathology, and functionality. Moreover, skin picking is often a cause of substantial distress and embarrassment for many individuals. Unfortunately, many patients with skin picking often fail to report it, believing it to be unrelated to therapeutic issues. Consequently, skin picking often goes undiagnosed and thus untreated.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study is 2-fold. First, unlike patients in previous psychiatric studies, individuals in the present sample had forms of skin picking that ranged from mild to severe. Therefore, the authors examined whether individuals with mild skin picking differed in their presentation of picking behavior (e.g., emotional experiences related to the picking) from individuals with severe skin picking. It is important to study the broad spectrum of skin picking because the knowledge obtained may be helpful in understanding the course of this behavior as well as assist in preventing the exacerbation of picking once it begins. Furthermore, the distinction between mild and severe skin picking may also help in the resolution of existing diagnostic categorization issues around this symptom as well as help generate more efficacious treatment recommendations.

Second, in an effort to further expand the existing skin picking knowledge base, phenomenological data related to the relationship between skin picking and anxiety, depression, and family involvement, as well as the emotional consequences of picking, were explored.

In order to provide a broader context for the current findings, the following is a brief review of current phenomenological information on skin picking. Several studies have investigated the characteristics and phenomenology of skin picking in a nonclinical student population. Keuthen et al.1 investigated phenomenological characteristics and psychiatric history in 105 college students. Seventy-eight percent endorsed some skin picking behavior. Of those who described themselves as engaging in skin picking, only 4.9% had severe tissue damage and significant distress, as well as impairment, which the investigators designated as self-injurious or severe skin picking. Seventy-eight students (95.1%) had noticeable tissue damage without impairments or distress, categorized as mild to moderate skin picking. These 78 individuals were compared to a clinical sample of 31 individuals with severe skin picking. They differed by the amount of time spent, areas picked, and implements used. Furthermore, higher tension before picking, higher satisfaction during picking, and higher levels of shame after picking also differentiated between the severe and the nonsevere pickers. Likewise, higher rates of depression and anxiety were reported in the individuals with severe picking. The authors concluded that skin picking as a symptom does not discriminate clinical from nonclinical populations.1

In another study of 133 college students in Germany, Bohne et al.2 reported that 91.7% had engaged in at least 1 occasion of skin picking in the previous year. Additionally, 57.9% reported recurrent skin picking, but only 8.3% engaged in skin picking for more than 30 minutes per day.2 Teng et al.3 found a 5.9% prevalence rate of severe skin picking in their college sample. Moreover, individuals who engaged in repetitive skin picking demonstrated higher somatic awareness.3

In a larger study looking at self-injurious behavior including skin picking, Croyle and Waltz4 found that 68% of their sample of 280 college students reported a history of some self-injurious behavior, with 31% engaging in mild injurious behavior characterized by nail biting and skin picking and 20% engaging in moderately injurious behavior including skin cutting and burning. Surprisingly, only 20% of the mildly self-injurious group and 45% of the moderately self-injurious group reported experiencing at least a moderately negative effect related to their self-injurious behavior. However, these behaviors were correlated with various dysfunctional behaviors, such as impulsive, somatic, and obsessive-compulsive characteristics. This study highlights the fairly common existence of self-injurious behavior, including skin picking, in the overall population and indicates, as well, that this behavior is often not of clinical significance given the low amount of distress it causes.4

Regarding research conducted with psychiatric populations, overall, Jenike et al.5 reported that about one half of psychiatrists have seen individuals with skin picking at one time or another in their practices. Notwithstanding, many of the clinical skin picking studies have been conducted with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) populations.

For example, Phillips and Taub6 examined skin picking behavior in a subset of individuals who were diagnosed with BDD (N = 123). They found that 27% of these individuals engaged in skin picking behavior. The individuals who picked their skin did not differ significantly in the severity of their BDD or in other demographic or diagnostic aspects. However, there was a higher number of individuals preoccupied with their skin in the skin picking group than in the nonpicking group. Compared to individuals who did not pick, significantly more individuals with skin picking engaged in camouflaging of the skin and grooming. Individuals who picked their skin also sought out dermatologic treatment significantly more than those who did not pick.6 In a more recent study of 176 individuals diagnosed with BDD, Grant et al.7 also found that individuals who picked their skin had an increased preoccupation with their skin, had comorbid trichotillomania or a personality disorder, used makeup for camouflage, and sought dermatologic treatment to deal with their skin preoccupation.

Phillips and Taub6 also found that the picking behavior usually results in an immediate reduction in tension, followed thereafter by feelings of shame and embarrassment and impairment in functioning. The latter occurs because the picking behavior often leads to damage of the skin, causing the person to be further upset by his or her appearance. The immediate reduction in distress seems to perpetuate the picking behavior in the future, despite the damage produced. While this scenario accounts for the skin picking behavior of many individuals with BDD, it by no means explains the triggers and behaviors of all individuals with skin picking.

In a broader clinical study, Wilhelm et al.8 studied 31 psychiatric outpatients who engaged in severe skin picking resulting in substantial tissue damage or marked distress and interference. All participants met criteria for an Axis I diagnosis, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), BDD, mood disorders, and alcohol abuse or dependence, and most had comorbid personality disorders. The study reported data on demographics, comorbidity, and skin picking characteristics for these subjects. However, this information represented only a small subset of individuals and did not include the majority of individuals who pick their skin in a milder or moderate form.8

Odlaug and Grant9 investigated skin picking in a clinical group of adults with a primary diagnosis of pathologic skin picking. They compared individuals with childhood and adult onset of skin picking behavior. Childhood onset was correlated with longer duration of picking behavior before seeking treatment, as well as with more unconscious picking. However, no difference was found in picking severity, comorbidity, and social functioning.9

In summary, skin picking has played a distressing lifelong role in the lives of many individuals. As a result, the present researchers have attempted to contribute to the literature on skin picking by expanding the phenomenological variables previously investigated and by studying the relationship between level of severity and picking behavior. This information may assist in clarifying unresolved issues (e.g., classification) in the skin picking literature, as well as hopefully lead to more efficacious treatment strategies and case conceptualizations.

METHOD

Participants

Forty participants were recruited by a private psychiatric treatment and research facility located in Great Neck, N.Y. All participants had a history of at least 1 psychiatric disorder. Although patients contacted the clinic for a variety of reasons, patients were recruited into the study, conducted from September 2002 through January 2003, if they acknowledged some level of skin picking behavior when asked during the initial interview, regardless of whether skin picking was the focus of treatment. All participants reported skin picking behavior that caused them some degree of emotional distress.

Prior to participation, all individuals were informed of the nature of the current investigation, and written informed consent was obtained. Subsequently, patients were asked to complete the questionnaires.

Measures

A self-report skin picking questionnaire compiled by the authors was used to assess demographic, symptom, and diagnostic information. History of past psychiatric diagnoses was ascertained via the self-report. Current psychiatric diagnoses were ascertained according to DSM-IV by a psychologist. Symptom checklists were used to identify target areas, implements, and triggers of skin picking. A Likert scale was used to assess the degree of awareness of, the duration of, and the interference from skin picking. In addition, using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from (0) “not present” to (5) “very intense,” participants rated their emotional response both prior to and after picking (e.g., satisfaction, being mesmerized, loss of control, tension, guilt, shame, and general negative feelings).

Participants were also given the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)10 and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).11 The BAI is a 21-item self-report measure that assesses the degree of physiologic anxiety symptoms. Subjects rate how much they are bothered by each of 21 sensations on a scale of 0 to 3, with higher numbers indicating more severe sensations. Overall scores may range from 0 to 63. The BAI has demonstrated high internal consistency as well as good concurrent and discriminate validity with other anxiety measures.10 The BDI is a 21-item self-report measure that assesses depressive symptoms, which are either vegetative or cognitive in nature. Scores on the BDI range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more severe levels of depression. The BDI has demonstrated high internal consistency as well as good concurrent validity.11

In addition, participants were administered the Self-Injury Interview (SII) (D. McKay, Ph.D., unpublished scale, Fordham University, 2005), which is a clinician-based interview under active development. The SII assesses the severity of self-harm behaviors, excluding suicidal behaviors. All participants answered the SII questions in reference to their skin picking behavior, not other self-injurious behaviors. The SII consists of 7 behaviorally anchored items rated on a scale ranging from 0 to 5. Potential scores on the SII can range from 0 to 35. The items assess the frequency, intensity, and severity of skin picking behavior and impulses. Initial data suggest adequate internal consistency reliability (r = 0.79) and an adequate univariate intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC = 0.76) for the SII.

Statistical Analyses

A series of univariate statistical procedures (t tests, correlations, etc.) were used to analyze the current data. It should be noted that as a result of incomplete responses from participants for various items on the self-report questionnaire, some percents throughout the article are based on Ns other than 40.

In order to investigate potential differences between mild and severe pickers, participants were classified into groups based on their score on the SII. Individuals who scored in the 25th percentile and below on the SII were deemed as having mild skin picking, while those in the 75th percentile and above were deemed as having severe skin picking. The emotional results of skin picking were determined using change scores for each of the emotional responses prior to and after picking.

All analyses were conducted using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

RESULTS

Participants

Participants ranged from 18 to 77 years of age (mean = 38.26, SD = 14.64). Seventy-five percent (30 of 40) of the participants were female and 97% (30 of 31) were white, with 1 individual (2% of 40) reporting race as “other.” Fifty-six percent (20 of 36) of the participants were single, 42% (17 of 40) were married, and 1 participant (2% of 40) was widowed. More than half of the participants (57% [21 of 37]) had at least some college credits or a college degree, with 27% (10 of 37) having completed some graduate school or a graduate degree and 16% (6 of 37) having completed some high school or a high school degree. Most of the participants were functioning well enough to be employed full-time (31% [11 of 35]), employed part-time (14% [5 of 35]), or attending school full-time (20% [7 of 35]). Seventeen percent of the participants (6 of 35) were unemployed, 11% (4 of 35) were homemakers, and 6% (2 of 35) were retired.

Results are reported first for the entire group. Later, individuals with mild versus severe skin picking are compared.

Psychiatric History

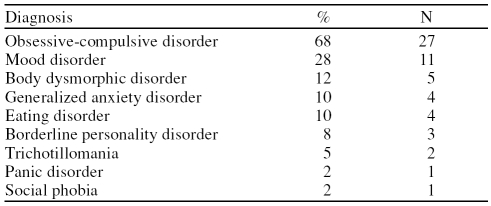

All of the participants had at least 1 current or past psychiatric diagnosis, with all participants reporting having an anxiety disorder. Most participants had more than 1 current Axis I diagnosis, with the most common combination being an anxiety and mood disorder (Table 1). More specifically, 68% of participants (27 of 40) reported having OCD, 12% (5 of 40) reported BDD, and 10% (4 of 40) reported generalized anxiety disorder. Five percent of participants (2 of 40) reported trichotillomania, and 2% (1 of 40) reported panic disorder and social phobia, respectively. Twenty-eight percent of participants (11 of 40) reported the presence of a mood disorder, and 10% (4 of 40), an eating disorder. Eight percent (3 of 40) reported a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. In addition, 36% of participants (12 of 33) reported a history of abuse (sexual, verbal, or emotional).

Table 1.

Psychiatric Diagnosis Demographics for Study Participants (N = 40)

Target Areas and Implements Used for Skin Picking

Participants reported multiple target areas for skin picking. Of these, the most common was the face (68% [27 of 40]), with cuticles (50% [20 of 40]) being the second most common target area. Picking was also frequently reported for the torso (back, 32% [13 of 40]; chest, 25% [10 of 40]) and limb regions (arms, 35% [14 of 40]; legs, 30% [12 of 40]). Other target areas included the neck (30% [12 of 40]), scalp (25% [10 of 40]), and ears (20% [8 of 40]). Forty-eight percent of participants (19 of 40) reported picking in other more idiosyncratic areas such as their feet and elbows.

While the majority of participants (95% [38 of 40]) utilized their fingers and/or fingernails, some also used other implements to facilitate their picking. The most common implements included tweezers (52% [21 of 40]), pins (32% [13 of 40]), and razors (5% [2 of 40]). In addition to using standard implements, 32% of participants (13 of 40) reported also using “other” implements (i.e., anything that was available at the time).

Skin Picking Triggers

The triggers that can precipitate an episode of skin picking can be emotional, perceptual, tactile, or environmental. Emotional triggers, such as general anxiety, were reported by every participant. Typical emotional triggers included general stress (95% [38 of 40]), interpersonal rejection (20% [8 of 40]), a sense of emptiness (42% [17 of 40]), and teasing (18% [7 of 40]).

Perceptual triggers were reported by most of the participants, with general skin imperfections reported by 80% of participants (32 of 40). Imperfections included such things as pimples and scabs (75% [30 of 40]), scars (25% [10 of 40]), mosquito bites (18% [7 of 40]), and other idiosyncratic, observed imperfections (40% [16 of 40]). Additional perceptual triggers included the perception of asymmetry in one's skin (35% [14 of 40]) and overall dissatisfaction with skin appearance (60% [24 of 40]). Thirty-two percent of participants (13 of 40) reported picking even at sites with no imperfections (i.e., healthy skin)

Tactile triggers included itchiness (40% [16 of 40]), sensations such as something underneath the surface of the skin (32% [13 of 40]), and the “right feeling” sensation (40% [16 of 40]). The most common environmental trigger was mirror checking (52% [21 of 40]). Many participants (50% [20 of 40]) also described anticipatory social anxiety as a trigger for picking.

Awareness, Duration, and Interference of Skin Picking

The majority of participants reported that their skin picking episodes took place when they were alone at home and stated that they were aware and attempted self-restraint. Seventy-four percent of participants (17 of 23) indicated that they were cognizant of their skin picking at the start of an episode more than half of the time, 13% (3 of 23) were aware half of the time, and 13% (3 of 23) were aware less than half of the time.

Skin picking episodes typically lasted from less than 5 minutes to 3 hours. Most participants reported that each individual skin picking episode usually lasted under an hour, with 9% (2 of 23) spending less than 5 minutes, 26% (6 of 23) spending 5 to 15 minutes, 13% (3 of 23) spending 15 to 30 minutes, and 26% (6 of 23) spending 30 minutes to 1 hour per incident. Twenty-six percent (6 of 23) reported 1 to 3 hours per episode. Over the course of a day, individuals may experience one or several skin picking episodes. In total over an entire day, 39% (9 of 23) spent less than 1 hour, 39% (9 of 23) spent 1 to 3 hours, 17% (4 of 23) spent 3 to 8 hours, and 4% (1 of 23) spent more than 8 hours picking per day.

As a result of skin picking, the majority of individuals experienced clinically significant interference in their daily functioning and lives. Although some participants experienced only mild to moderate distress (13% [3 of 23]), the vast majority were significantly distressed as a result of their skin picking. Forty-three percent (10 of 23) found their symptoms to be disturbing but manageable, 30% (7 of 23) found the symptoms to be very distressing, and 13% (3 of 23) described constant and disabling distress in relation to their symptoms.

Physical Damage Attributed to Skin Picking

As a result of skin picking, 58% of participants (11 of 19) experienced a moderate degree of tissue damage. Mild tissue damage was reported by 26% of individuals (5 of 19), and severe tissue damage was reported by 5% of participants (1 of 19). Eleven percent (2 of 19) reported no damage at all. Numerous dermatologic complications were reported as a result of skin picking. Infection was the most common occurrence (18% [6 of 33]). Bleeding (6% [2 of 33]) and inflammation (3% [1 of 33]) were likewise reported. For some individuals with particularly severe forms of skin picking, corrective surgery was necessary (6% [2 of 33]). Moreover, 38% of participants (9 of 24) had sought some sort of other professional medical help for their skin picking, including visiting their general practitioner or internist.

Emotional Results of Skin Picking

In general, participants reported that they did not obtain substantial relief from their negative emotions after skin picking. In fact, 28% (10 of 36) reported experiencing no relief whatsoever, 19% (7 of 36) experienced relief on only a few occasions, and 11% (4 of 36) experienced some degree of relief. Fourteen percent (5 of 36) experienced relief half of the time, while 17% (6 of 36) reported experiencing relief a majority of the time. Only a small proportion (11% [4 of 36]) always experienced relief.

With regard to the intensity of specific emotions, prior to skin picking, individuals reported feeling an intense sense of loss of control, tension, and general negative feelings. They also reported feeling some guilt and shame and being mesmerized. When prepicking and postpicking emotions were compared, individuals reported a significant increase in the intensity of feelings of physical pain (t = 6.67, p = .000), guilt (t = 5.63, p = .000), shame (t = 6.31, p = .000), and general negative feelings (t = 4.45, p = .000). They also experienced a significant increase in the intensity of their sense of satisfaction (t = 3.32, p = .002), as well as a significant but slight decrease in tension (t = −3.45, p = .001) after picking. There was no significant change in participants' sense of control over the situation or their feelings of being mesmerized. Therefore, picking did not effectively decrease negative emotions, and, in fact, it seemed to increase several negative feelings.

Relationships Between Skin Picking and Depression and Anxiety

The BAI and BDI were given to investigate whether there were significant correlations between anxiety and depression and picking behavior. The degree of physiologic anxiety experienced by the participants, as measured by the BAI, ranged from 0 to 48 (mean = 16.41, SD = 11.42), reflecting that participants experienced physiologic symptoms ranging from “none” to “severe anxiety.” The correlation between the extent of skin picking behavior, as measured by the SII, and the BAI was not significant (r = −0.04, p = .82). Severity of depressive symptoms, as measured by BDI scores of 0 to 51 (mean = 18.59, SD = 13.27), also ranged from “none” to “severe depressive symptoms.” The correlation between the SII and BDI was not significant (r = 0.17, p = .38).

Relationship Between Skin Picking and Familial Variables

Eighty-eight percent of the participants (28 of 32) reported having a family psychiatric history, including 43% (16 of 37) who reported having family members who engaged in skin picking. As a result, participants reported that their skin picking was often a focus of family discussion. Additionally, participants reported both supportive (19% [5 of 26]) and unsupportive (50% [13 of 26]) family reactions to their problem, as well as mixed reactions (31% [8 of 26]) ranging from empathy, assistance, and emotional support to fighting over the behavior and a general lack of understanding and empathy.

Treatment History

With regard to treatment history, 79% of the participants (27 of 34) had a history of some psychological treatment. Ninety-four percent of the participants (32 of 34) were currently on at least 1 psychiatric medication, with medication types including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, stimulants, mood stabilizers, anxiolytics, and neuroleptics. While most participants had some sort of treatment history, a minority (30% [12 of 40]) had actually sought treatment specifically for their skin picking behavior. This finding was particularly noteworthy as most participants reported that their skin picking was a source of distress for which they would like intervention. Interestingly, however, most participants were unaware that any treatment (and in particular, psychological treatment) existed for skin picking.

Comparison of Characteristics Between Individuals With Mild and Individuals With Severe Skin Picking

As stated earlier, in order to examine whether skin picking differed between individuals with mild and with severe skin picking, participants were divided on the basis of their responses to the SII. Nine of 40 individuals (22%) were designated as engaging in mild skin picking (mean SII score = 10.56, SD = 1.00), with scores ranging from 6 to 16. Sixteen of 40 individuals (40%) were designated as engaging in severe skin picking (mean SII score = 23.50, SD = 0.45), with scores ranging from 22 to 27.

There were no significant differences between the groups on any demographic variables. The 2 groups differed in the degree of distress (t = −2.35, p = .05) and the extent of physical damage (t = −3.06, p = .01) caused by their skin picking, with the severe group experiencing more distress and more damage than the mild group. Surprisingly, however, they did not differ with respect to any other variables. Specifically, the 2 groups did not differ with regard to the degree of emotional responses both before and after picking, including the sense of loss of control, tension, guilt, shame, being mesmerized, and general negative feelings.

DISCUSSION

Skin picking is an underreported symptom because patients are usually ashamed of the behavior, do not specifically seek treatment for it, and report it only upon specific questioning by a clinician. Unfortunately, many clinicians are unaware of the prevalence and importance of the symptom and thus do not probe for it. Moreover, the absence of skin picking from mention as a symptom per se in the DSM-IV further adds to the lack of interest and information available about this behavior. It is for this reason that the present authors wish to draw attention to what appears to be a relatively common symptom among psychiatric patients.

Skin picking behavior of differing severity levels appears to exist within a psychiatric outpatient population and interferes with the life of the sufferer. While the behavior often occurs in the presence of other psychiatric disorders, it provides its own source of distress and impairment. Skin picking primarily occurs on the face and cuticles, but the torso, arms, and legs may also be involved. As reported above, skin picking is a time-consuming symptom, often lasting from 5 to 60 minutes per episode and totaling an hour or more per day. Interference from skin picking can be intense, and dermatologic injuries (e.g., infections, bleeding) are often present.

Individuals with mild and with severe skin picking differed in the degree of distress and skin damage they experienced. It should be noted that while individuals with severe skin picking experienced overall higher levels of distress due to their behavior, the distress was related mostly to the higher level of skin damage they experienced. Many of the participants in the study discussed the distress that was caused by seeing the extent of the damage they had caused, long healing times, and the social consequences of others' noticing the damage.

While individuals with severe skin picking experienced more distress and skin damage from their behavior than individuals with mild skin picking, the immediate emotional experience prior to and after picking did not differ significantly. This finding is noteworthy in that the degree of skin picking cannot be accurately classified on the basis of the emotional buildup that precedes the skin picking episode or the immediate emotional outcome of the behavior. This finding differs from the findings of Keuthen et al.,1 in which the severe and nonsevere pickers differed in degrees of tension, satisfaction, and shame surrounding a picking episode. The difference in our findings may be accounted for by the fact that mild skin picking in a student population may be generally less severe than mild skin picking in a clinical outpatient population.

Given that the current study did not find emotional differences based on skin picking severity, other factors must determine why individuals vary in the severity of this behavior. Although it is outside the scope of this article, possible explanations for severity differences may lie in factors external to the skin picking behavior per se, such as the general level of impulse control or availability of other coping mechanisms. This is an area in need of further research. Moreover, it is possible that the potential functions (e.g., mood regulation, grooming) that skin picking may serve vary between clinical and nonclinical populations and, therefore, contribute to the observed differences across studies.

On the basis of the current findings, skin picking triggers include emotional (e.g., interpersonal relationships), tactile (e.g., itchiness), and perceptual (e.g., skin imperfections) sources. Interestingly, the degree of anxiety or depression does not seem to be associated with the severity of the picking behavior, and, contrary to popular belief, skin picking is not an anxiety relief for the majority of individuals. This finding is interesting in light of the evidence that self-mutilative behaviors have been found to serve this function.

Specifically, Nock and Prinstein12 demonstrated that self-mutilative behaviors may serve automatic (e.g., emotional regulation) and/or socially reinforcing (e.g., secondary gain) functions. Future research should continue to examine the role of functionality in skin picking. In particular, special attention should be aimed at identifying additional functions that skin picking may serve, as well as identifying individual differences that may predict which functions certain individuals use skin picking to satisfy. Regardless, it is recommended that practitioners incorporate an appropriate functional behavior assessment once skin picking behavior is discovered in order to select appropriate treatment strategies based on the underlying function(s) of the behavior.

The current findings have additional important implications for treatment. First, because of the potential for substantial physical damage from skin picking, it is important to establish a collaborative relationship between psychologists and dermatologists in order to provide a more comprehensive treatment plan. Moreover, due to either actual or perceived social consequences of picking, these individuals may be more prone to avoidance behavior; therefore, treatment planning should incorporate both behavioral exposure and supplementary cognitive components to assist patients in coping with their own and/or others' reactions to their behavior, as well as to increase functioning across all major life domains. For example, it is important for practitioners to monitor the beliefs of individuals regarding what, specifically, the damage means to them, as well as what potential effect it may have on their body image and subsequent behavior. Furthermore, due to the mixed reactions of family members, practitioners should consider involving significant others in treatment as a means of behavioral coaching, as well as to model supportive modes of communicating to patients during already painful picking episodes.

Despite the potential utility of the current findings, certain limitations should be noted. The first limitation of this study is the high prevalence of individuals with skin picking who have a diagnosis of OCD. This is due to the fact that the institute where the patients were recruited is known for its treatment of OCD. However, despite this high prevalence (68%), many of these patients had other diagnoses, and, overall, there was a good representation of a variety of clinical conditions (e.g., eating disorders, mood disorders).

Another limitation to the study was the lack of a comparison group of individuals with skin picking who are seen solely by dermatologists. Those who seek psychiatric treatment and those who do not may be different. Finally, the measures that were used relied on self-reported data. Therefore, these measures were subject to potential reporting biases such as social desirability, unreliability, and temporal factors.

Future research efforts should utilize alternative assessment methods including multiple informants and repeated measures across time and locations.13 Moreover, evidence suggests that concepts investigated via self-report measures do not always hold experimentally. This fact has significant relevance regarding the functional assessment of skin picking behaviors. Specifically, as mentioned above, skin picking may serve different functions for different individuals. Future research should utilize experimental methods of assessment (e.g., analog assessment14) in order to increase the reliability and validity of identifying functionality in general, as well as to help identify potential functions of skin picking presently unrecognized by patients and clinicians.

CONCLUSION

It is the present authors' contention that the information provided by this study will give clinicians a framework for understanding skin picking and allow for proper questioning of their patients about its common characteristics. The authors encourage clinicians to ask their patients about skin picking during the initial interview, since most often skin picking is not reported spontaneously even though it can be deleterious in the life of the individual.

Footnotes

The authors report no financial or other affiliations relevant to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

- Keuthen NJ, Deckersbach T, and Wilhelm S. et al. Repetitive skin-picking in a student population and comparison with a sample of self-injurious skin pickers. Psychosomatics. 2000 41:210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohne A, Wilhelm S, and Keuthen N. et al. Skin picking in German students: prevalence, phenomenology, and associated characteristics. Behav Modif. 2002 26:320–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng EJ, Woods DW, and Twohig MP. et al. Body-focused repetitive behavior problems: prevalence in a nonreferred population and differences in perceived somatic activity. Behav Modif. 2002 26:340–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croyle KL, Waltz J.. Subclinical self-harm: range of behaviors, extent, and associated characteristics. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(2):332–342. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenike MA, Baer L, and Minichiello W. OCD Theory and Management. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Year Book. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Taub SL.. Skin picking as a symptom of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1995;31:279–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Menard W, Phillips KA.. Pathologic skin picking in individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Keuthen NJ, and Deckersbach T. et al. Self-injurious skin picking: clinical characteristics and comorbidity. J Clin Psychiatry. July1999 60(7):454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odlaug BL, Grant JE.. Childhood-onset pathologic skin picking: clinical characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(4):388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, and Brown G. et al. An inventory measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988 56:893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. New York, NY: Psychological Corporation. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ.. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 200472:885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ.. Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:140–146. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TI, Rose R, Chisholm S.. What is the function of nail biting: an analog assessment study. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:989–995. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]