Sir: Individuals with mental illness frequently have poor physical health, are overweight or obese, and have higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, respiratory disease, and cardiovascular disease, all of which may contribute to early mortality.1–3 Persons with mental illness often experience weight gain and metabolic dysregulation during the course of their illness and treatment.1,4,5 Effective management of persons with mental illness may require a holistic approach to care, one that includes not just their mental health but monitoring and improving their physical health as well.6 This management could be provided in the primary care setting just as it is for the non–mentally ill population, including advice on smoking cessation, weight reduction, and exercise.

The Solutions for Wellness Personalized Program7 is an ongoing 6-month lifestyle intervention program that was initiated in July 2001 for patients with mental illness living in the community. To increase awareness that community-dwelling individuals with mental illness will participate in wellness intervention programs to improve their health and well-being, we report outcomes from over 7000 program completers.

Method

Patients were provided program information and an enrollment form during a visit to their health care provider. In order to participate in the program, patients were not required to meet any criteria, such as DSM diagnosis, receipt of psychopharmacologic treatment, incident weight, or risk for weight gain. The decision to enroll was entirely up to the patient, and conduct of the program was independent of the health care provider, mental health center, or program sponsor. As part of the enrollment process, patients completed a questionnaire that included questions regarding diet, exercise, sleep, and stress management, which provided information for the development of a personalized menu planner and exercise program. Participants signed an agreement at enrollment that allowed the use of non-identifiable data from the questionnaire and subsequent monthly follow-up surveys to be used to monitor program outcomes.

The results presented here were summarized from self-reported responses on follow-up surveys returned from July 1, 2002, through December 31, 2004. Participants who returned 5 follow-up surveys (surveys 2–6) were considered program completers; all others were considered noncompleters. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used to summarize data. Mean changes in weight and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) from enrollment to program completion were analyzed using last observation carried forward (LOCF), and monthly changes in weight and BMI were analyzed using observed cases. Differences between completers and noncompleters were evaluated using t tests at the 5% significance level.

Results

Over 5500 physicians across the United States referred patients to the program. Overall, most of the participants were women (84%) with an average age in their early 40s, and over 60% were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2). There were 7836 completers (21%) and 29,412 noncompleters (79%). The most common reason for enrolling in the program reported by completers and noncompleters, respectively, was the desire to improve their well-being (71.3% and 68.6%), although some indicated that they wanted to feel better about themselves (15.9% and 18.3%) and others wanted to improve their diet (6.3% and 6.5%) or fitness (6.5% and 6.6%).

At enrollment, program completers and noncompleters, respectively, reported that they were ready to improve their diet (98.8% and 99.0%), become more physically active (96.8% and 97.2%), sleep better (82.1% and 83.6%), and reduce stress (94.9% and 95.3%). On the second follow-up survey, completers and noncompleters reported that they were eating healthier (67% and 61%), had begun exercising (42% and 39%), had improved sleep habits (46% and 44%), and had reduced their levels of stress (57% and 55%). At the end of the program, over 90% of the completers reported that they had switched to healthier diets; over 80% had become more physically active, were sleeping better, and had less stress; and over 95% reported that they were confident in their ability to maintain these lifestyle changes. For the noncompleters, responses were summarized from their last available survey, which indicated that 85% had switched to healthier diets; over 70% were more physically active, were sleeping better, and had less stress; and over 90% were confident that they could continue with their changes in lifestyle.

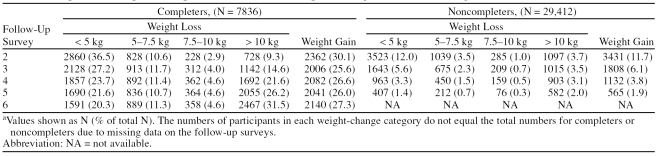

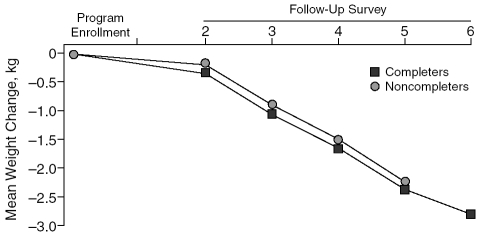

BMI calculated from height and weight reported at enrollment indicated that 87% of completers and 86% of noncompleters were overweight or obese. The results from each follow-up survey for both completers and noncompleters indicated mean weight changes reflecting weight loss, although some participants gained weight (Table 1). Overall, the mean change in weight was −4.5 kg (–10.0 lb) for those participants who lost weight and the mean change in weight was +4.2 kg (9.3 lb) for those who gained weight. The mean weight change in program completers was −2.77 kg (–6.16 lb) with a corresponding mean change in BMI of −1.0 kg/m2, and both of these changes were significantly greater than those reported by the noncompleters (–0.97 kg [–2.16 lb], p < .001; BMI of −0.35 kg/m2, p < .001, LOCF). However, mean weight changes over time between completers and noncompleters were not significantly different in an observed case analysis (Figure 1). Among the overweight participants, the mean weight changes were −0.88 kg (–2.0 lb) for completers and −0.15 kg (–0.3 lb) for noncompleters. Among obese participants, mean weight changes were −4.1 kg (–9.1 lb) for completers and −1.5 kg (–3.3 lb) for noncompleters.

Table 1.

Categorical Changes in Weight From Baseline in Program Completers and Noncompletersa

Figure 1.

Mean Weight Change From Program Enrollment for Program Completers and Noncompleters

Self-reported outcomes from participants in this multifaceted wellness intervention program demonstrated that persons with mental illness living in the community can make lifestyle changes that improve their physical health and well-being. Most of the participants in this program were overweight or obese when they enrolled, and many of them reported having lost some weight, even those who did not complete the program. These results are similar to those from studies of commercial weight loss programs in nonpsychiatric overweight and obese subjects that reported weight loss in all participants, including those who discontinued early.8,9

Retention at the 6-month endpoint in this analysis was 21%, which is similar to findings in a naturalistic study of a commercial weight loss program that had enrolled over 60,000 clients and reported 22% retention at 26 weeks.9 However, retention rates in open enrollment programs are considerably lower than those from randomized trials of weight management. In a yearlong study of 160 overweight or obese subjects who were randomized to 1 of 4 commercial diet programs, retention at 6 months was 62% and at 12 months was 58%.8 In a 2-year trial10 of overweight or obese subjects randomized to a commercial diet program (N = 211) or self-help group (N = 212), retention at 6 months was 83% and 81%. A 12-week clinical trial in overweight/obese persons with mental illness randomized to behavioral intervention or usual care reported a completion rate of 75%.11 The higher retention rates in clinical trials may be due to the selective screening of potential participants and, perhaps, self-selection bias of successful participants.10

Attrition from weight-loss programs has been associated with age younger than 50 years,12,13 depression/emotional difficulties,13–15 smoking,13 physical inactivity,13 medical comorbidity,13 and unrealistic weight goals.16 The average age of the participants in this program was early 40s, and they were presumed to have a mental illness, were perhaps physically inactive, and may not have been ready to make lifestyle changes.7 However, since the reason for participant dropout was not collected, it would be difficult to speculate which aspects of the program could be improved to increase completion rates.

Although program participation was associated with some weight loss and positive lifestyle changes, these results are greatly limited by the nature of their origin. Self-reported data from a loosely defined population constrain generalization, particularly to any diagnostic group of persons with mental illness. However, the positive results reported here are mirrored by similar findings reported by others for cohorts of persons with mental illness who participated in weight loss/lifestyle intervention programs.17,18 Furthermore, the impact of lifestyle changes on dimensions of physical health is limited by the lack of clinical laboratory measures of glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides, which define the metabolic state associated with being overweight or obese.

In conclusion, the overall long-term experience with the Solutions for Wellness Personalized Program demonstrates that persons with mental illness have the desire to improve their health and well-being. Physicians treating persons with mental illness should encourage them to participate in programs that provide education and support for lifestyle changes, which may help them achieve these goals.

Acknowledgments

Suppported by Eli Lilly and Company.

Drs. Hoffmann, Bushe, and Ahl and Mr. Meyers are employees and/or stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Ind. Dr. Greenwood and Ms. Benzing are employees of Patient Marketing Group, Princeton, N.J., which is currently contracted by Eli Lilly and Company to implement this program.

References

- Keck PE, McElroy SL.. Bipolar disorder, obesity, and pharmaco-therapy-associated weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(12):1426–1435. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder SR, Essock SM, and Miller AL. et al. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 161(8):1334–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff DC, Sullivan LM, and McEvoy JP. et al. A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schizophr Res. 2005 80(1):45–53.16198088 [Google Scholar]

- Bushe C, Leonard B.. Association between atypical antipsychotic agents and type 2 diabetes: review of prospective clinical data. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;47:S87–S93. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.47.s87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susce MT, Villanueva N, and Diaz FJ. et al. Obesity and associated complications in patients with severe mental illnesses: a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005 66(2):167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L, Yeomans D. Do guidelines for severe mental illness promote physical health and well-being? J Psychopharmacol. 2005 19suppl 6. 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann VP, Ahl J, and Meyers A. et al. Wellness intervention for patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005 66(12):1576–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, and Griffith JL. et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005 293(1):43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley CE, Barlow CE, and Greenway FL. et al. Retention rates and weight loss in a commercial weight loss program. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007 31(2):292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heshka S, Anderson JW, and Atkinson RL. et al. Weight loss with self-help compared with a structured commercial program: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003 289(14):1792–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon JS, Choi JS, and Bahk WM. et al. Weight management program for treatment-emergent weight gain in olanzapine-treated patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a 12-week randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 67(4):547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honas JJ, Early JL, and Frederickson DD. et al. Predictors of attrition in a large clinic-based weight-loss program. Obes Res. 2003 11(7):888–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MM, Niaura R, and King TK. et al. Depression, smoking, activity level, and health status: pretreatment predictors of attrition in obesity treatment. Addict Behav. 1996 21(4):509–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yass-Reed EM, Barry NJ, Dacey CM.. Examination of pretreatment predictors of attrition in a VLCD and behavior therapy weight-loss program. Addict Behav. 1993;18(4):431–435. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90060-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi E, Dalle Grave R, and Mannucci E. et al. Complexity of attrition in the treatment of obesity: clues from a structured telephone interview. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006 30(7):1132–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, and Molinari E. et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients and treatment attrition: an observational multicenter study. Obes Res. 2005 13(11):1961–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushe C, Haddad P, and Peveler R. et al. The role of lifestyle interventions and weight management in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2005 19suppl 6. 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendlebury J, Bushe CJ, and Wilgust HJ. et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss in patients with severe mental illness through a behavioral treatment programme in the UK. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007 115(4):286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]