Abstract

Croup is a common childhood illness. The majority of children presenting with an acute onset of barky cough, stridor and indrawing have croup. A careful history and physical examination is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of croup, and to rule out potentially serious alternative causes of upper airway obstruction. Nebulized adrenaline is effective for the temporary relief of airway obstruction. Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment in children with croup of all levels of severity.

Keywords: Child, Corticosteroids, Croup, Inhaled adrenaline

Abstract

Le faux croup est une maladie infantile courante. La majorité des enfants qui présentent une toux aboyante, un stridor et un tirage souffrent de faux croup. Il faut procéder à une anamnèse attentive et à un examen physique pour confirmer le diagnostic de faux croup et écarter les autres causes d’obstruction des voies aériennes supérieures au potentiel grave. L’adrénaline en aérosol offre un soulagement temporaire efficace de l’obstruction des voies aériennes. Les corticoïdes constituent le principal mode de traitement des enfants atteints de faux croup, quelle que soit la gravité de la maladie.

Croup (laryngotracheobronchitis) is a common cause of upper airway obstruction in children. The annual incidence is 1.5 to 6 per 100 children younger than six years of age (1). Croup is most prevalent in the late fall to early winter months. Although common in children between six months and three years of age, it can also occur in children as young as three months and as old as 15 years of age (1). It is rarely reported in adults (2). Boys are affected more often than girls. Common causes are parainfluenza types 1 and 3. Influenza A and B, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, metapneumovirus and mycoplasma have also been isolated (1,3).

Croup is a clinical diagnosis requiring no specific laboratory or radiological investigations when the history and physical examinations are typical (Table 1). Particular attention should be paid to symptoms such as nonspecific cough, rhinorrhea and fever, which may precede the characteristic seal-like barky cough. Symptoms are usually worse at night, and are aggravated by agitation and crying. Obstructive symptoms generally resolve within 48 h, but a small percentage of children remain symptomatic for up to five to six days (4). Physical findings include stridor, chest wall retractions and respiratory distress ranging from mild to severe. Signs of respiratory failure include reduced respiratory effort and breath sounds, lethargy, and pallor or cyanosis. Severity of croup may be broadly categorized by clinical observation (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Differential diagnoses for children who present with acute onset of stridor

| Differential diagnosis | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Bacterial tracheitis (most common diagnosis after croup) | High fever, toxic appearance and poor response to nebulized adrenaline. |

| Epiglottitis (relatively rare since introduction of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine) | Absence of barky cough, sudden onset of high fever, dysphagia, drooling, toxic appearance, anxious appearance and sitting slightly forward in the ‘sniffing’ position. |

| Occult foreign object (very rare) | Acute onset of stridor and presence of occult foreign body most commonly lodged in the upper esophagus. |

| Laryngeal diphtheria (very rare) | History of inadequate immunization may be found. Prodrome of pharyngitis 3 days. Low-grade fever, hoarseness, barking cough, stridor and dysphagia. Characteristic membranous pharyngitis on examination. |

| Acute allergic reaction or angioneurotic edema (rare) | Rapid onset of dysphagia and stridor, and possible cutaneous allergic signs such as urticarial rash. |

TABLE 2.

Classification of severity of croup at time of initial assessment

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|

| Without stridor or significant chest wall indrawing at rest | Stridor and chest wall indrawing at rest without agitation | Stridor and indrawing of the sternum associated with agitation or lethargy |

Data from reference 7

The majority of children can be safely managed at home. Very few require artificial airway support (5). Over 60% of children diagnosed with croup have mild symptoms, approximately 4% are hospitalized and approximately one in 5000 children are intubated (approximately one in 200 hospitalized children) (4–6).

Goals of therapy are to decrease the duration and severity of symptoms, minimize anxiety of the child and his/her parents, and to decrease intubations, hospitalizations and return visits to physicians.

THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

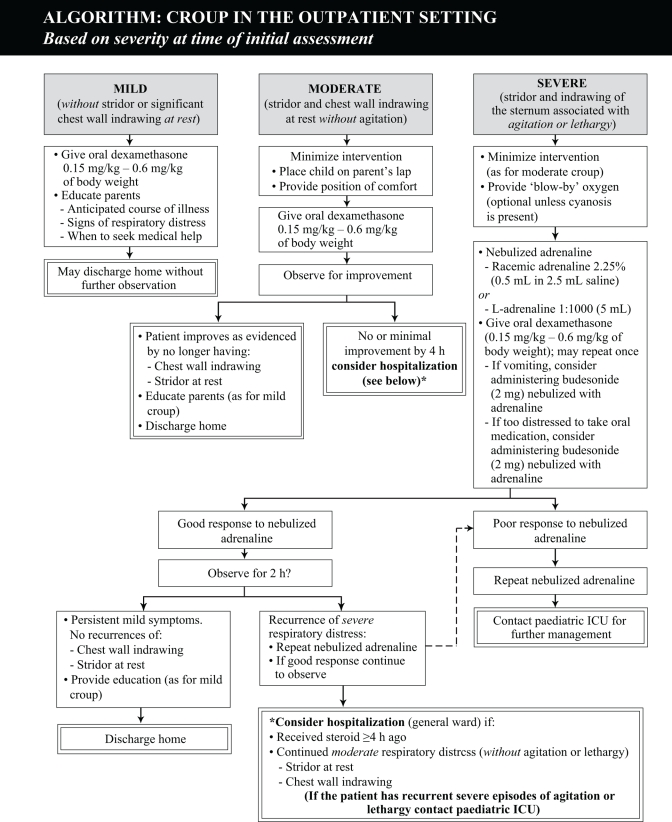

Children with mild croup can be managed in the office setting, while those with moderate or severe croup should be referred to an emergency department for treatment and observation (Figure 1).

NONPHARMACOLOGICAL CHOICES

Keep children calm by ensuring a relaxed and reassuring atmosphere to minimize oxygen demand and respiratory muscle fatigue. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of mist therapy (7–14). Placing children in mist tents, a wet and cold environment, and separating them from their parents may provoke anxiety and agitation and should be avoided (13).

Oxygen therapy, in conjunction with corticosteroids and adrenaline, is reserved for children with hypoxia and significant respiratory distress. It should never be forced on a child, especially if it results in significant agitation. ‘Blow-by’ administration of oxygen through a plastic hose with the end opening held within a few centimeters of the child’s nose and mouth is often the most beneficial way of administration. Helium-oxygen mixtures may benefit children with severe respiratory distress (15–18), but there is insufficient evidence to advocate their use outside this setting. Administration of helium-oxygen mixtures has been proposed because there is a potential for the lower density helium gas (relative to nitrogen) to decrease turbulent airflow in a narrowed airway. Practical limitations include the limited fractional concentration of inspired oxygen in a child with significant hypoxia.

PHARMACOLOGICAL CHOICES (TABLE 3)

TABLE 3.

Drugs used for croup

| Drug class | Drug | Dose and duration | Comments | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenergic agonist | Adrenaline, racemic Vaponefrin (sanofiaventis, Canada) | 0.5 mL of 2.25% solution diluted in 2.5 mL of normal saline or sterile water via nebulizer | Racemic adrenaline and L-adrenaline are equivalent in terms of effect and safety (53).

Adrenaline has no effect on clinical symptoms beyond 2 h, consequently patients should not be discharged from medical care before 2 h following treatment (51,52). |

$ |

| L-adrenaline generics | 5 mL of 1:1000 (1 mg/mL) solution via nebulizer | See L-adrenaline, racemic. | $ | |

| Corticosteroids | Dexamethasone generics | 0.15 mg/kg to 0.6 mg/kg taken orally or intramuscularly once. May repeat dose in 6 h to 24 h | Oral dexamethasone is well-absorbed and achieves peak serum concentrations as rapidly as with intramuscular administration (59) (without the pain of intramuscular injection).

Several controlled trials suggest oral and intramuscular administration yield equivalent results (30,31,60). Experience suggest that clinical improvement will begin as early as 2 h to 3 h after treatment (22). No evidence to suggest that multiple doses provide additional benefit over a single dose. Reduces rate and duration of intubation, rate and duration of hospitalization and rate of return to medical care (20–29). |

$ |

| Budesonide, Pulmicort Nebuamp (AstraZeneca Canada) | 2 mg (2 mL) solution via nebulizer | Inhaled budesonide has been shown to be equivalent to oral dexamethasone in several studies (22,35,37) but is substantially more expensive.

May be useful in patients with vomiting and severe respiratory distress. Can administer budesonide and adrenaline simultaneously. |

$$ |

*Cost of one dose; includes drug cost only. $<$1; $$=$1 to $5

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy for croup, regardless of clinical severity (19). Corticosteroids have been shown to reduce intubations, duration of intubation, need for reintubation, need for additional inhaled adrenaline, duration of hospitalization, rate of hospitalization and rate of return to a health care practitioner for persistent croup symptoms (20–29). Dexamethasone and inhaled budesonide relieve croup symptoms as early as 3 h after treatment (22).

Dexamethasone is equally effective when given orally (30,31). While an older meta-analysis of controlled trials (21) suggested that higher doses yield a clinically important response in a greater proportion of patients, four more recent controlled trials have found no difference in clinical outcomes between dexamethasone doses ranging from 0.15 mg/kg to 0.6 mg/kg (26,32–34). It is not known whether multiple doses of corticosteroids provide greater benefit than a single dose. Given the short duration of croup symptoms in the majority of patients, a single dose of corticosteroid may be sufficient.

It has been demonstrated that oral or intramuscular administration of corticosteroids is either equivalent or superior to the inhaled route (22,35–38). Routine use of inhaled budesonide is limited by cost. Patients with severe croup, or who are near respiratory failure, may benefit from the simultaneous administration of inhaled budesonide and nebulized adrenaline. The combination may be more effective than adrenaline alone.

Corticosteroids should be avoided in children with a known immunodeficiency or recent exposure to varicella (39–42).

Adrenaline (adrenergic agonist)

Based on historical data, nebulized adrenaline in children with severe croup substantially reduces the number requiring an artificial airway (43). Adrenaline reduces respiratory distress within 10 min of administration and lasts longer than 1 h (44–46).

Effects of adrenaline wear off within 2 h of administration (44). Although patients treated with adrenaline may return to their ‘baseline’ severity, they do not routinely develop worse symptoms (44,46). Both retrospective and prospective studies (22,47–52) suggest that patients treated with adrenaline may be safely discharged if their symptoms do not recur for at least 2 h to 3 h after treatment.

L-adrenaline 1:1000 is as effective and safe as the racemic form (53). A single-size dose (0.5 mL of 2.25% racemic adrenaline or 5 mL of L-adrenaline 1:1000) is used in all children regardless of size. Children’s relative size of tidal volume is thought to modulate the dose of drug actually delivered to the upper airway (54–57).

There is one report (58) of an otherwise normal child with severe croup treated with three nebulizations of adrenaline within 1 h who developed ventricular tachycardia and a myocardial infarction. If back-to-back adrenaline is considered necessary, the treating physician should contact a paediatric intensivist as soon as possible regarding further treatment and transport.

Analgesics

Analgesics may provide some degree of increased comfort by reducing fever and pain.

Antitussives and decongestants

No experimental studies have been published regarding the potential benefit of antitussives or decongestants in children with croup. There is no rational basis for their use.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not effective in the treatment of croup but may be used in suspected cases of bacterial superinfection. Intravenous antibiotics are generally recommended because of the potential for rapid deterioration.

Figure 1.

Croup in the outpatient setting (based on severity of initial assessment). ICU Intensive care unit

REFERENCES

- 1.Denny FW, Murphy TF, Clyde WA, Collier AM, Henderson FW. Croup: An 11-year study in a pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1983;71:871–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong MC, Chu MC, Leighton SE, van Hasselt CA. Adult croup. Chest. 1996;109:1659–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.6.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho HK. Human metapneumovirus and lower respiratory tract disease in children. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1788–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc040541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson DW, Williamson J. Croup: Duration of symptoms and impact on family functioning. Pediatr Research. 2001;49:83A. (Abst) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown JC. The management of croup. Br Med Bull. 2002;61:189–202. doi: 10.1093/bmb/61.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson DW, Williamson J. Health care utilization by children with croup in Alberta. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:185A. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson D, Klassen T, Kellner J. Diagnosis and management of croup: Alberta Medical Association clinical practice guidelines. 2005 < http://www.albertadoctors.org/bcm/ama/ama-website.nsf/AllDocSearch/87256DB000705C3F87256E05005534E2/$File/CROUP.PDF?OpenElement> (Version current at July 11, 2007)

- 8.Johnson D. Croup. In: Rudolf M, Moyer V, editors. Clinical Evidence. 12 edn. London: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2004. pp. 401–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavine E, Scolnik D. Lack of efficacy of humidification in the treatment of croup: Why do physicians persist in using an unproven modality? CJEM. 2001;3:209–12. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500005571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neto GM, Kentab O, Klassen TP, Osmond MH. A randomized controlled trial of mist in the acute treatment of moderate croup. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:873–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scolnik D, Coates AL, Stephens D, Da Silva Z, Lavine E, Schuh S. Controlled delivery of high vs low humidity vs mist therapy for croup in emergency departments: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1274–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.11.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourchier D, Dawson KP, Fergusson DM. Humidification in viral croup: A controlled trial. Aust Paediatr J. 1984;20:289–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1984.tb00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry R. Moist air in the treatment of laryngotracheitis. Arch Dis Child. 1983;58:577. doi: 10.1136/adc.58.8.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore M, Little P. Humidified air inhalation for treating croup. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD002870. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002870.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan PG. Efficacy of helium–oxygen mixtures in the management of severe viral and post-intubation croup. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1979;26:206–12. doi: 10.1007/BF03006983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGee DL, Wald DA, Hinchliffe S. Helium-oxygen therapy in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1997;15:291–6. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(97)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terregino CA, Nairn SJ, Chansky ME, Kass JE. The effect of Heliox on croup: A pilot study. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:1130–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber JE, Chudnofsky CR, Younger JG, et al. A randomized comparison of helium-oxygen mixture (heliox) and racemic epinephrine for the treatment of moderate to severe croup. Pediatrics. 2001;197:E96. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell K, Wiebe N, Saenz A, et al. Glucocorticoids for croup. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD001955. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001955.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ausejo M, Saenz A, Pham B, et al. The effectiveness of glucocorticoids in treating croup: Meta-analysis. BMJ. 1999;319:595–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7210.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kairys SW, Olmstead EM, O’Connor GT. Steroid treatment of laryngotracheitis: A meta-analysis of the evidence from randomized trials. Pediatrics. 1989;83:683–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson DW, Jacobson S, Edney PC, Hadfield P, Mundy ME, Schuh S. A comparison of nebulized budesonide, intramuscular dexamethasone, and placebo for moderately severe croup. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:498–503. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjornson CL, Klassen TP, Williamson J, et al. Pediatric Emergency Research Canada Network A randomized trial of a single dose of oral dexamethasone for mild croup. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1306–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tibballs J, Shann FA, Landau LI. Placebo-controlled trial of prednisolone in children intubated for croup. Lancet. 1992;340:745–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92293-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geelhoed GC. Sixteen years of croup in a western Australian teaching hospital: Effects of routine steroid treatment. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:621–6. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geelhoed GC, Macdonald WB. Oral dexamethasone in the treatment of croup: 0.15 mg/kg versus 0.3 mg/kg versus 0.6 mg/kg. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1995;20:362–8. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950200605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luria JW, Gonzalez-del-Rey JA, DiGiulio GA, McAneney CM, Olson JJ, Ruddy RM. Effectiveness of oral or nebulized dexamethasone for children with mild croup. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1340–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.12.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klassen TP, Feldman ME, Watters LK, Sutcliffe T, Rowe PC. Nebulized budesonide for children with mild-to-moderate croup. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:285–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson DW, Schuh S, Koren G, Jaffee DM. Outpatient treatment of croup with nebulized dexamethasone. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:349–55. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donaldson D, Poleski D, Knipple E, et al. Intramuscular versus oral dexamethasone for the treatment of moderate-to-severe croup: A randomized, double-blind trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rittichier KK, Ledwith CA. Outpatient treatment of moderate croup with dexamethasone: Intramuscular versus oral dosing. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1344–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chub-Uppakarn S, Sangsupawanich P. A randomized comparison of dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg versus 0.6 mg/kg for the treatment of moderate to severe croup. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:473–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fifoot AA, Ting JY. Comparison between single-dose oral prednisolone and oral dexamethasone in the treatment of croup: A randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:51–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2006.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alshehri M, Almegamsi T, Hammdi A. Efficacy of a small dose of oral dexamethasone in croup. Biomed Res (Aligarh) 2005;16:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geelhoed GC, Macdonald WB. Oral and inhaled steroids in croup: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1995;20:355–61. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950200604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedersen LV, Dahl M, Falk-Petersen HE, Larsen SE. [Inhaled budesonide versus intramuscular dexamethasone in the treatment of pseudo-croup. ] Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160:2253–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klassen TP, Craig WR, Moher D, et al. Nebulized budesonide and oral dexamethasone for treatment of croup: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1629–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cetinkaya F, Tüfekçi BS, Kutluk G. A comparison of nebulized budesonide, and intramuscular, and oral dexamethasone for treatment of croup. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:453–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dowell SF, Bresee JS. Severe varicella associated with steroid use. Pediatrics. 1993;92:223–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Academy of Allergy and Immunology, Committee on Drugs. Inhaled corticosteroids and severe viral infections. News and Notes. 1992;3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.New drug not routinely recommended for healthy children with chickenpox. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Paediatric Society; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Revised label warns of severe viral problems with corticosteroids. FDA Med Bull. 1991;21:3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adair JC, Ring WH, Jordan WS, Elwyn RA. Ten-year experience with IPPB in the treatment of acute laryngotracheobronchitis. Anesth Analg. 1971;50:649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westley CR, Cotton EK, Brooks JG. Nebulized racemic epinephrine by IPPB for the treatment of croup: A double-blind study. Am J Dis Child. 1978;132:484–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1978.02120300044008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taussig LM, Castro O, Beaudry PH, Fox WW, Bureau M. Treatment of laryngotracheobronchitis (croup). Use of intermittent positive-pressure breathing and racemic epinephrine. Am J Dis Child. 1975;129:790–3. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1975.02120440016004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kristjánsson S, Berg-Kelly K, Winsö E. Inhalation of racemic adrenaline in the treatment of mild and moderately severe croup. Clinical symptom score and oxygen saturation measurements for evaluation of treatment effects. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:1156–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb18270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rizos JD, DiGravio BE, Sehl MJ, Tallon JM. The disposition of children with croup treated with racemic epinephrine and dexamethasone in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:535–9. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ledwith CA, Shea LM, Mauro RD. Safety and efficacy of nebulized racemic epinephrine in conjunction with oral dexamethasone and mist in the outpatient treatment of croup. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:331–7. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kunkel NC, Baker MD. Use of racemic epinephrine, dexamethasone, and mist in the outpatient management of croup. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1996;12:156–9. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199606000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prendergast M, Jones JS, Hartman D. Racemic epinephrine in the treatment of laryngotracheitis: Can we identify children for outpatient therapy? Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:613–6. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kelley PB, Simon JE. Racemic epinephrine use in croup and disposition. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:181–3. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(92)90204-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corneli HM, Bolte RG. Outpatient use of racemic epinephrine in croup. Am Fam Physician. 1992;46:683–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waisman Y, Klein BL, Boenning DA, et al. Prospective randomized double-blind study comparing L-epinephrine and racemic epinephrine aerosols in the treatment of laryngotracheitis (croup) Pediatrics. 1992;89:302–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wildhaber JH, Mönkhoff M, Sennhauser FH. Dosage regimens for inhaled therapy in children should be reconsidered. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38:115–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schüepp KG, Straub D, Möller A, Wildhaber JH. Deposition of aerosols in infants and children. J Aerosol Med. 2004;17:153–6. doi: 10.1089/0894268041457228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fink JB. Aerosol delivery to ventilated infant and pediatric patients. Respir Care. 2004;49:653–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Janssens HM, Krijgsman A, Verbraak TF, Hop WC, de Jongste JC, Tiddens HA. Determining factors of aerosol deposition for four pMDI-spacer combinations in an infant upper airway model. J Aerosol Med. 2004;17:51–61. doi: 10.1089/089426804322994460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butte MJ, Nguyen BX, Hutchison TJ, Wiggins JW, Ziegler JW. Pediatric myocardial infarction after racemic epinephrine administration. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e9. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.1.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richter O, Ern B, Reinhardt D, Becker B. Pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone in children. Pediatr Pharmacol (New York) 1983;3:329–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Amir L, Hubermann H, Halevi A, Mor M, Mimouni M, Waisman Y. Oral betamethasone versus intramuscular dexamethasone for the treatment of mild to moderate viral croup: A prospective, randomized trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:541–4. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000230552.63799.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]