Do you have an adolescent-friendly practice? Adolescents, especially boys, underutilize the health care system (1). Youth tend to use emergency departments or drop-in clinics, making it difficult to develop an ongoing relationship with a medical professional. Even though they are generally a healthy population, we know that adolescents have medical needs that must be addressed. Twenty per cent of teenagers in North America have a serious health problem, most commonly, obesity, asthma and eating disorders (2). Furthermore, the top three causes of death in the 12- to 18-year-old age group – motor vehicle traffic-related injury, suicide and homicide (3) – are not related to disease, but to modifiable risk-taking behaviours. Altering these behaviours requires partnership with the teenager. Thus, building a trusting and ongoing relationship with a provider becomes central to preventive health maintenance in this population. The goal of the present paper was to enhance the health provider’s ability to partner with teens by offering clinical pearls in the area of history-taking, providing practical pointers for negotiating the difficult issues around confidentiality and tips on integrating the role of families in the setting of adolescent-friendly health care.

YOUTH TALK

Adolescents are often remarkably forthcoming about themselves when they feel safe. Keys to creating such an atmosphere includes the assurance of confidentiality, a non-judgemental approach and recognition of the youth’s personal autonomy. Conveying a nonjudgemental attitude requires critical examination of one’s own beliefs, acceptance that those beliefs might not be universally shared, and recognition of how the teenagers’ beliefs and actions might pose a potential threat to their health. Focusing on health promotion rather than value promotion allows health care providers to build a nonjudgemental and inviting atmosphere.

Interview adolescents alone

No matter how open teenagers are with their parents, or how low risk their behaviour may appear to be, sensitive issues should be broached with the teenager alone. Teenagers will spare their parents from hearing information that is in some way painful or that will risk altering the parent’s perception of the teenager. Creating that ‘alone time’ depends on how the office is set up, as well as the age of the adolescent. Calling patients from the waiting room yourself allows some control as to who will be brought into the examining room, initially. Older adolescents typically feel comfortable coming in alone, and parents can be reassured that they will have an opportunity to speak with you later in the encounter. With the younger or very anxious adolescent, or in situations in which the parent is already in the room (such as an emergency room visit), an abbreviated history can be obtained which should address the immediate concerns of the parents, as well as allow the parent or caregiver to provide key details (this is also an obvious time to obtain the family history). Parents can then be asked for some time alone with the adolescent as a means of getting to know them better and addressing any of their own health concerns. For the most part, parents are usually quite willing to do this, if a few minutes are taken upfront to explain the concept of adolescent-friendly care.

Screen for high-risk behaviours

The popular HEADSS (4) psychosocial screening tool is presented in Appendix A. There is no doubt that addressing psychosocial risks is time consuming. Teens are less likely to be forthcoming if they perceive that their provider is going through the motions versus being genuinely interested. Therefore, a quick run-through of a checklist is likely to have a low yield. Pose open-ended questions and practice active listening to favour a more thorough discussion. When short on time, one strategy is to address one or two psychosocial domains at each visit. Otherwise, assume you get only ‘one shot’ at risk reduction, given teens’ sporadic use of the health care system. Because of the high mortality and morbidity associated with depression, all teens should be screened for depression, beyond the HEADSS interview (Appendix B) (5).

Paper and pen (6) or on-screen tests (7) have been developed to prescreen for high-yield areas of discussion. This can provide an efficient alternative to the 30 min to 45 min required for the HEADSS interview. The obvious caveat is that all positive responses must be addressed.

Get personal

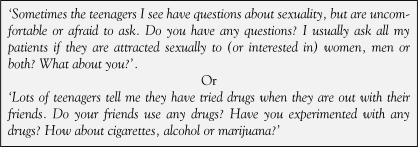

Because the HEADSS interviewing strategy provides a graduated approach from less sensitive to more sensitive areas, it can serve the dual purpose of screening and developing a rapport with the teenager. Providers often worry that questions about sexuality and substance use seem voyeuristic. Both parties are more at ease when the goal of identifying potential health risks is clearly articulated and is seen by both as part of the medical monitoring of teenagers. Normalizing the questions (Figure 1) is a useful technique to foster open dialogue. Furthermore, teenagers should be informed that they have the right not to answer if they do not want to.

Figure 1.

Examples of how to ask about sexuality and substance use, using normalizing statements

Attend to both explicit and implicit information

Teenagers will sometimes use peculiar phrasing or awkward pauses to cue you to an issue they want to talk about, but are not sure how to broach. The long pause before answering whether they are ‘sexually active’ may be because they are embarrassed, but it may also be because they are trying to decide whether you are interested in hearing about heterosexual vaginal intercourse only, or other sexual interactions as well.

Provide the facts

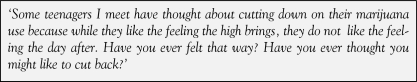

During the HEADSS psychosocial interview, provide feedback in a factual manner as issues arise instead of an authoritative lecture at the end of the visit. Teenagers are interested in a care provider who displays honesty, experience and knowledge (8). Furthermore, teenagers usually see through the practice of physicians using ‘their’ slang expressions in an effort to try to relate to them. Remember that while your ultimate objective in risk behaviour counselling may be elimination of all risk behaviour, this is not a realistic objective for any one patient over their lifetime, let alone for one interview. Motivational interviewing (9) is a technique proven to have benefits in this population. This approach can be summarized by providing feedback during the history (educating around risks and benefits, while promoting a sense of responsibility within the teenager). Furthermore, you want to assess where the teenager stands with regard to their openness to change (Figure 2). This ranges from ‘not even considering it’ to ‘thinking about it’ to ‘ready for action’.

Figure 2.

Example of assessing openness to change

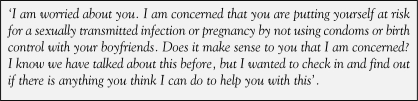

It may help to envision your role as attempting to gently nudge adolescents to the next stage. When they are ready for action, you should be armed with a few strategic suggestions and a list of community resources that are available to help. When the situation arises, where high-risk behaviours do pose a risk to the young person’s health, use ‘I’ statements to express concern instead of the ‘You’ statements, which imply blame and are perceived as alienating (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Example of an “I” statement of concern

Involve the patient in the decision of when the parent is present and what information is shared

Some patients prefer to have the parent present during the physical examination, while others do not. Ask patients whether they would prefer you to explain the diagnosis and treatment plan to the patient and parent together. If the parent or caregiver is brought in just at the end of the visit, be clear to establish with the teenager what information they would like to keep confidential. Partner with the teenager by anticipating questions that their parents may have, and discuss with them how they would want their concerns to be addressed.

WALKING THE TALK: THE IMPORTANCE OF CONFIDENTIALITY

Providing confidential health care to adolescents is not always straightforward, and often causes a great sense of uneasiness among medical practitioners (10). Uncertainties can arise as a result of complex dilemmas that may challenge the provider’s ethical as well as legal responsibilities. (11) Adolescent patients ‘buy’ into the doctor-patient relationship with an expectation that their confidences will not be revealed to others without their consent. For paediatricians and family doctors who have cared for children, and have come to know their parents well, the concept of not disclosing medical information to the parents can be uncomfortable. Despite this, it is vitally important that physicians offer confidential care.

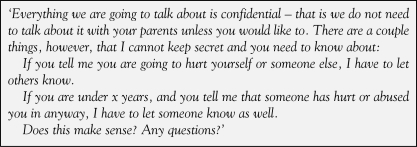

As a group, adolescents repeatedly tell us that confidential care matters (8,12). Ford et al (13) showed that when a health visit is started with a brief discussion about confidentiality (Figure 4), adolescents are more willing to disclose sensitive information, and report a greater intent to return to the health provider for further care. Furthermore, the number one reason given by teenagers for not accessing health care is confidentiality (14). Interestingly, a recent study (15) examined whether adolescents who forgo health care due to confidentiality concerns differ from adolescents who forgo health care for other reasons. Boys with confidentiality concerns were more likely to suffer depressive symptoms and experience suicidal ideation and suicide attempts than their nonconfidentiality-concerned counterparts. Girls with confidentiality concerns were also more likely to report these mental health risks and risky sexual behaviour.

Figure 4.

Example of an explanation of confidentiality and its limits

Laws and practices pertaining to the extension and limits of confidentiality for teenagers vary across provinces and are beyond the scope of the present article. In general, adolescent patients should be aware that the limits of confidentiality apply specifically to issues of safety. For example, risk of self-harm, harm to others, and abuse and risk of abuse in youth.

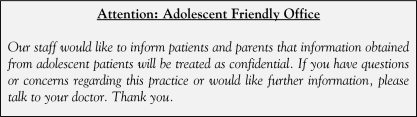

Educating adolescents and their caregivers about confidentiality for teenagers is key. For example, posters outlining the practice of confidential health care can be placed in waiting areas in an effort to introduce the topic as well as to set the tone for an adolescent-friendly practice (Figure 5). Table 1 lists other suggestions to make your practice teenager friendly.

Figure 5.

Example of a poster outlining the practice of confidentiality

TABLE 1.

Tips for making your practice ‘teenager friendly’

|

ALL IN THE FAMILY: BUILDING BRIDGES

Adolescents do not live in isolation; rather, they are interdependent on their families and friends as they make the transition into adulthood. In the vast majority of situations, families are an incredible source of support for the well-being of their youth. The family-centred care (FCC) approach is based on the understanding that the family is the primary source of strength and support, and recognizes that the perspectives and clinical information provided by both the adolescent and the family are very important for decision making (16). The Canadian Paediatric Society also has a family-friendly adolescent health care statement (17) which is also useful.

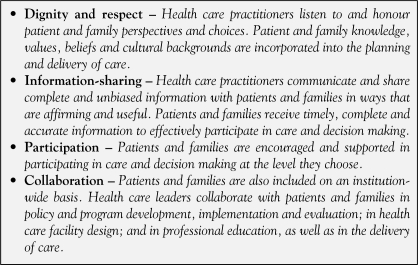

At first glance, it may seem that the tenets of FCC (Figure 6) may be in conflict with respecting the rights of the adolescent concerning confidentiality and privacy, but in actuality, they work to protect all family members’ rights and access to information, and foster active participation in the youth’s care.

Figure 6.

Core concepts of patient- and family-centred care. Data from reference 16

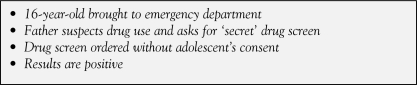

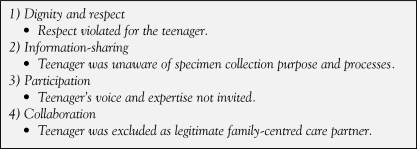

But how does the FCC approach apply to adolescent health? (Figures 7 and 8 list examples). Overall, the approach of FCC prepares youth to participate in medical decision making, and assists families of youth to move from primary decision maker to consultants. It also supports medical professionals to see the young adult as the leader of the health care team and helps build bridges between the youth and their family when dealing with challenging and sensitive issues, while respecting their basic rights to confidentiality.

Figure 7.

The ‘secret’ drug screen request

Figure 8.

The family-centred approach as applied to the ‘secret’ drug screen

CONCLUSION

Although the task of counselling a teenager, who has experienced a sexual assault, is suffering from an eating disorder or may be struggling with depression, can appear to be quite daunting, asking the ‘tough’ questions and providing an empathic ‘space’ allows providers to initiate conversations that will hopefully provide the first step to comprehensive adolescent health care. Adolescents who are concerned about confidentiality, ‘vote with their feet’. It is imperative to review the right to, as well as the limits of, confidentiality with every teenager who is interviewed, regardless of the setting. The failure of adolescents to seek appropriate medical care, not only contributes to morbidity and mortality in this age group, but also creates public health challenges in many domains. Families are often youths’ greatest resource and models, such as the FCC, can be applied to help navigate decisions and dilemmas while balancing caregivers’ legitimate concerns with youths’ right to confidential health care.

APPENDIX A

The HEADSS psychosocial screening tool

| Home | Tell me what your homelife is like? |

| Who is at home? | |

| How does everyone get along? | |

| Family members/ages/health/substance use/psychiatric history? | |

| Education and employment | Name of school/grade/marks |

| Likes/dislikes at school – why? | |

| Activities | What do you like to do for fun on weekends? |

| Do you feel like you have enough friends? | |

| Do you have a best friend? | |

| Sports/exercise? | |

| Drugs and dieting | Have you tried cigarettes? Alcohol? Marijuana? |

| (If experimenting, cover all class of drugs: hallucinogens, amphetamines, rave drugs, anabolic steroids, inhalants, injectible drugs, crack cocaine and over-the-counter medication) Do you have concerns with your weight/shape? | |

| Sexual identity and activity, suicide and safety | Are you interested in the same sex, opposite sex or both? |

| Are you dating someone now? Are you having sexual intercourse? What do you use for protection? (sexually transmitted infections or pregnancy?) | |

| Have you heard of emergency contraception? | |

| Have you ever had a pelvic examination, a Pap smear or a sexually transmitted infection screening? | |

| Have you lost interest in things you used to enjoy? | |

| Have you had any thoughts about hurting/killing yourself? Others? | |

| Have you been feeling sad, down or depressed much of the time? | |

| Do you regularly wear seatbelts in the car, helmets when biking, etc. | |

| Does anyone at home own a gun? | |

| Has anyone ever hurt you or touched you in an inappropriate way? |

Adapted from <http://chipts.ucla.edu/assessment/Assessment_Instruments/Assessment_files_new/assess_headss.htm> (Version current at December 21, 2007).

APPENDIX B

Screening questions for depression

|

APPENDIX C

Internet resources for teenagers

|

Versions current at December 11, 2007

REFERENCES:

- 1.Newacheck PW, Stoddard JJ, Hughes DC. Children’s access to health care: The role of social and economic factors. In: Stein RE, editor. Health Care for Children. New York: United Hospital Fund; 1997. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Utilization of physician offices by adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 1999;104:35–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistics Canada The young and the reckless. < http://www.statcan.ca/english/kits/cyb1999/health/art1.htm> (Version current at December 11, 2007)

- 4.Wilkes MS, Anderson S. A primary approach to adolescent health care. West J Med. 2000;172:177–82. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.3.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatcher-Kay C, King CA. Depression and suicide. Pediatr Rev. 2003;24:363–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The American Medical Association Guidelines for adolescent preventive services: Younger and middle-older adolescent, and parent/guardian questionnaire. < http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/upload/mm/39/young.pdf>, < http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/upload/mm/39/periodic.pdf> and < http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/upload/mm/39/parenteng.pdf> (Version current at December 11, 2007)

- 7.Paperny DM. Computer-assisted detection and intervention in adolescent high-risk health behaviors. J Pediatr. 1990;116:456–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82844-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginsburg KR, Menapace AS, Slap GB. Factors affecting the decision to seek health care: The voice of adolescents. Pediatrics. 1997;100:922–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson SJ, Gerstle M, Feldstein SW. Brief interventions and motivational interviewing with children, adolescents, and their parents in pediatric health care settings: A review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1173–80. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnick MD, Litman TJ, Blum RW. Physician attitudes toward confidentiality of treatment for adolescents: Findings from the Upper Midwest Regional Physicians Survey. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13:616–22. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90377-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morton WJ, Westwood M. Informed consent in children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 1997;2:329–33. doi: 10.1093/pch/2.5.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng TL, Savageau JA, Sattler AL, DeWitt TG. Confidentiality in health care. A survey of knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes among high school students. JAMA. 1993;269:1404–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.269.11.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford CA, Millstein SG, Halpern-Felsher BL, Irwin CE., Jr Influence of physician confidentiality assurances on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information and seek future health care. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278:1029–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein JD, Wilson KM, McNulty M, Kapphahn C, Collins KS. J Adolesc Health. Vol. 25. 1999. Access to medical care for adolescents: Results from the 1997 Commonwealth Fund Survey of the Health of Adolescent Girls; pp. 120–30. (Erratum in 1999;25:312) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehrer JA, Pantell R, Tebb K, Shafer MA. Forgone health care among US adolescents: Associations between risk characteristics and confidentiality concern. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:218–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Institute for Family-Centered Care Patient- and family-centered care: Tools for change. < http://www.familycenteredcare.org/tools/index.html> (Version current at December 11, 2007)

- 17.Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Medicine Committee [Principal author: R Tonkin] Paediatr Child Health 1997. Vol. 2. Family friendly adolescent health care; pp. 356–7. [Google Scholar]