Abstract

Apoptotic and antiproliferative activities of small heterodimer partner (SHP) nuclear receptor ligand (E)-4-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamic acid (3-Cl-AHPC), which was derived from 6-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxylic acid (AHPN), and several carboxyl isosteric or hydrogen bond-accepting analogues were examined. 3-Cl-AHPC continued to be the most effective apoptotic agent, whereas tetrazole, thiazolidine-2,4-dione, methyldinitrile, hydroxamic acid, boronic acid, 2-oxoaldehyde, and ethyl phosphonic acid hydrogen bond-acceptor analogues were inactive or less efficient inducers of KG-1 acute myeloid leukemia and MDA-MB-231 breast, H292 lung, and DU-145 prostate cancer cell apoptosis. Similarly, 3-Cl-AHPC was the most potent inhibitor of cell proliferation. 4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-3-chlorophenyltetrazole, (2E)-5-{2-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-2-chloro-4′-hydroxy-4-biphenyl]-ethenyl}-1H-tetrazole, 5-{4-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-3-chlorobenzylidene}thiazolidine-2,4-dione, and (3E)-4-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-2-chloro-4′-hydroxy-4-biphenyl]-2-oxobut-3-enal were very modest inhibitors of KG-1 proliferation. The other analogues were minimal inhibitors. Fragment-based QSAR analyses relating the polar termini with cancer cell growth inhibition revealed that length and van der Waals electrostatic surface potential were the most influential features on activity. 3-Cl-AHPC and the 3-chlorophenyltetrazole and 3-chlorobenzylidenethiazolidine-2,4-dione analogues were also able to inhibit SHP-2 protein-tyrosine phosphatase, which is elevated in some leukemias. 3-Cl-AHPC at 1.0 µM induced human microvascular endothelial cell apoptosis but did not inhibit cell migration or tube formation.

Introduction

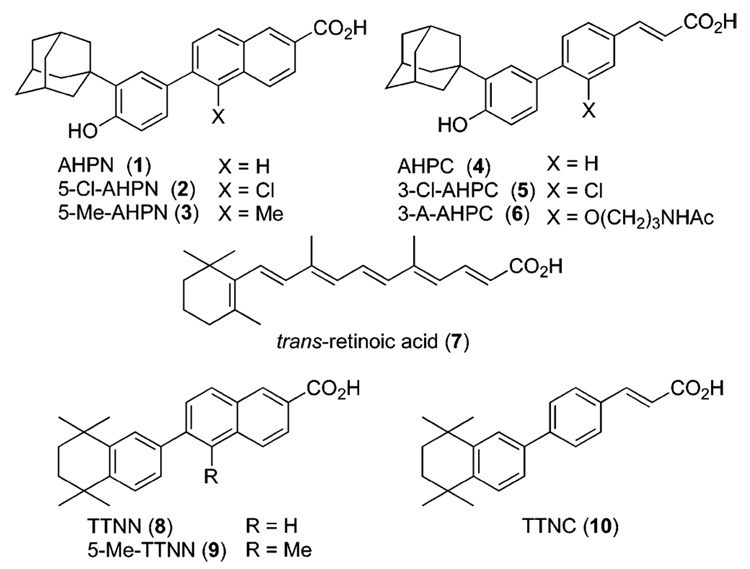

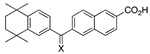

In investigating the effects of retinoids on cancer cell proliferation, we first noticed that the retinoid 6-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxylic acid (AHPNa/ CD437, 1 in Figure 1)1,2 displayed the atypical functions of inducing the cell-cycle arrest and initiating the apoptosis of MCF-7 breast cancer and other cancer cell lines.3,4 Further research led to our identification of (E)-4-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamic acid (3-Cl-AHPC, 5)5 that retained these functions but not that exhibited by classical retinoids, namely the transcriptional activation of the retinoic acid nuclear receptor (RAR) subtypes to induce the transcription of genes regulated by trans-retinoic acid (trans-RA, 7) and its synthetic retinoid analogues.5–8 By inducing apoptosis of leukemia cells obtained from AML patients,5 5 may have potential as a therapeutic agent for treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML). It also has the ability to induce apoptosis of cells from a variety of human cancer cell lines, including those derived from breast, lung, and prostate cancers.9 Moreover, apoptosis induced by 1 and 5 was found to be independent of the sensitivity of the cancer cell line to growth regulation by trans-RA or its p53 status,3,4 either of which is therapeutically advantageous because during cancer progression the ability of the trans-RA–RARα complex to regulate proliferation or induce differentiation through induction of expression of the tumor suppressor gene RARβ is lost10,11 and the tumor suppressor gene p53 becomes dysfunctional or lost in about 50% of tumors.12,13

Figure 1.

Structures of AHPN (1), 5-Cl-AHPN (2), 5-Me-AHPN (3), AHPC (4), 3-Cl-AHPC (5), 3-A-AHPC (6), trans-RA (7), TTNN (8), 5-Me-TTNN (9), and TTNC (10).

Recently, we identified the first synthetic small-molecule ligands, 3-Cl-AHPC (5) and several analogues, for the nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner (SHP; NR0B2),14 which hitherto had only a putative ligand-binding domain and was classified as an orphan receptor. SHP is an atypical member of the steroid/thyroid hormone nuclear receptor family of transcription factors because it lacks the amino terminal sequence (AB), canonical DNA-binding domain (C), and hinge region (D) that are typical of other nuclear receptors and predominately functions as a transcriptional repressor through the binding of one of its three NR box motifs (LXXLL) to the activation function 2 (AF-2) site in the ligand-binding domain of its dimeric nuclear receptor partner. SHP has been found to bind such nuclear receptors as the androgen, aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator, constitutive activated, estrogen, farnesoid, glucorticoid, liver X, pregnane X, peroxisome proliferator-activated, retinoic acid, retinoid X, thyroid hormone, TR3/nur77/NGFB-I, and vitamin D receptors.15–21 SHP modulates gene transactivation or suppression induced by its heterodimeric partner by recruiting histone deacetylases 1, 3, or 6, G9a histone 3 K9 methyltransferase, and other members of the Sin3a-Swi/Snf repressor complex.17

Tumor growth can be inhibited directly by inducing cancer cell death or indirectly by inhibiting tumor neovascularization (angiogenesis), a process that provides a conduit for delivery of nutrients to and removal of metabolic byproducts from the tumor.22 Tumor vasculature also provides a route for cancer cells to escape from the tumor and move to secondary metastatic sites.23 For these reasons, we explored the abilities of 3-Cl-AHPC (5) and its analogues to function as anticancer and antiangiogenic agents. We also undertook an analogue generation program to determine the pharmacophoric elements necessary to confer apoptotic activity to 5. Here, we report the effects of 5 and several analogues on the proliferation and functions of human microvascular endothelial (HMVE) cells and the impact that replacing the carboxylic acid group of 5 with other hydrogen-bond acceptors or isosteric-like groups has on cancer cell growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

Analogue Design

As a consequence of reports that therapeutic retinoids and RAR ligands such as trans-RA (7) and 9-cis-RA can cause adverse effects in cancer patients,24,25 a major facet of our design strategy has been introducing groups and scaffold modifications onto the AHPN scaffold that reduced interaction with the RAR subtypes. This strategy was first accomplished for the design of AHPC (4) by comparing the activities of members of our retinoid library in assays for retinoid activity with those of the retinoid TTNN (8)26 from which AHPN (1) was originally derived.2 These assays, which historically have been widely used to assess retinoic acid-like activity, were (i) induction of keratin granule formation in vitamin-A-deficient hamster trachea in organ culture (TOC assay), which was developed by Sporn and co-workers;27 (ii) induction of differentiation in F9 embryonic teratocarcinoma cells (F9 assay);28 and (iii) inhibition of the induction of the proliferative enzyme ornithine decarboxylase in mouse epidermis by the tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), which was developed by Verma and Boutwell (ODC assay).29 These assays have been reviewed by Sporn and Roberts.30 On the basis of its lower activities in the TOC and ODC assays, the cinnamic acid analogue (TTNC, 10)31 of TTNN (8) was deemed to have less retinoid activity (Table 1). Similarly, the 3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl ring of 1 conferred lower retinoid activity than the 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-5,5,8,8-tetramethyl-2-naphthalenyl ring of 826 did in the ODC assay32 (Table 1), just as it was subsequently found by Shroot and co-workers to have lower activity in the RAR transcriptional activation assay.1 Therefore, the two ring systems, 3-(1-adamantyl)-4-hydroxyphenyl and (E)-cinnamic acid, were joined at their 1-and 4-ring positions, respectively, to produce AHPC (4).

Table 1.

Classical Retinoid Assays Used To Compare Activities of Comformationally Restricted Retinoids with Those of trans-Retinoic Acida

| IC50 value (nM) |

ID50 value (nmol) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| retinoid | TOCb | F9c | ODCd |

| trans-RA (7) | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.19 |

| TTNN (8) | 0.007 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| TTNC (10) | 0.32 | 0.3 | 7.5 |

| AHPN (1) | nde | nd | 3.1 |

| 5-Me-TTNN (9) | 0.08 | 3.0 | 66 |

For overview of these assays see Sporn and Roberts (1984).

TOC assay, concentration required to reverse keratinization in 50% of vitamin A-deficient hamster tracheas in organ culture after 10 days as determined by analysis of stained cross-sections for the absence of keratin and keratohyaline granules.

F9 assay, concentration required to induce terminal differentiation in 50% of F9 murine embryonic teratocarcinoma cells in culture after 3 days as measured by secreted plasminogen activator activity.

ODC assay, topical dose of retinoid preapplied to mouse dorsal epidermis at 1 h before TPA leading to 50% inhibition in level of ornithine decarboxylase induced by TPA (7.5 nmol) at 4.5 h after TPA application as measured by the release of labeled CO2 from [14C]ornithine by epidermal homogenates. TPA, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate.

nd, not determined.

AHPC (4) effectively induced cancer cell apoptosis and exhibited lower activities in the TOC, F9, and ODC assays than AHPN; however, we observed that mice injected intravenously with AHPC displayed symptoms of retinoid-like toxicity. The structure of 4 was later reported as ST1926, which was found to have antileukemic activity.33 Recently, 4 was also found to transactivate the RARs α, β, and γ on a DR5-tk-CAT reporter construct in transfected COS-7 cells.34 Its half-maximal activation concentrations (AC50s) were 8-, 2.8-, and 4.7-fold higher, respectively, than those of trans-RA (7), thereby supporting our design strategy.

As Table 1 indicates, introduction of a substituent at the 5-position of the naphthalene ring in TTNN (8), which is ortho to the diaryl bond, reduced the retinoid activity of 5-Me-TTNN (9) in the TOC, F9, and ODC assays. By adapting this substitution strategy, namely introducing a chloro group adjacent to the diaryl bond of AHPN (1) and AHPC (4), we achieved a further reduction in RAR interaction by energetically hindering the diaryl rings of 5-Cl-AHPN (2)35 and 3-Cl-AHPC (5)5 from assuming a small dihedral angle on binding to the RARs.6 According to molecular dynamics calculations on 2, the increased dihedral angle for the 1′,4-diaryl bond caused the adamantyl group to interfere with the local dynamics of RARγ helix H12 to prevent the formation of the AF-2 site with helices H3 and H4 to which coactivator proteins bind to recruit the transcriptional complex necessary for retinoid-induced gene transcription.

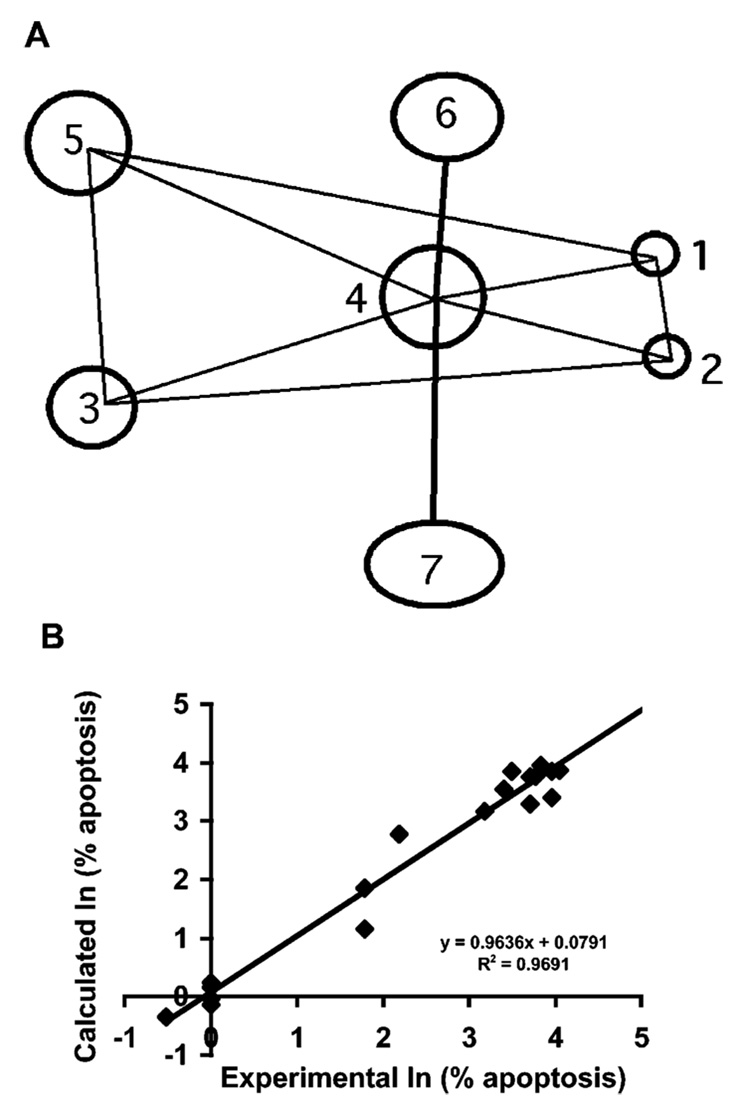

We recently undertook quantitative structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies to identify the core recognition elements on 55 analogues of AHPN (1) and AHPC (4) that were necessary to induce the apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells after treatment at 1.0 µM for 96 h. The ‘overlap rule’ was used to align the training set in SYBYL QSAR, and the comparative molecular similarity index analysis (CoMSIA) electrostatic, hydrophobic, and steric fields were computed on a grid surrounding the overlapped ligands. The resulting CoMSIA analysis for apoptosis induction in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells [ln(% apoptosis)] resulted in a predictive R2 of 0.78 and an un-cross-validated R2 of 0.95 with a standard error of 0.45. This seven-point descriptive model is illustrated in Figure 2A. Key polar points include two adjacent hydrogen-acceptor groups 1 and 2 and a hydrogen-donor/acceptor group 3. The predictivity of this initial model was sufficient to score apoptosis induced by analogues similar in character to those in the training set. For example, if 3-Cl-AHPC (5) and (E)-3-{5-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-2-thienyl}propenoic acid were left out of the training set and the CoMSIA model were used to predict their ability at 1.0 µM to induce MDA-MB-231 apoptosis, the predicted versus experimental results were: 92% versus 43% for 5 and 0.8% versus 1% for the thienylpropenoic acid (Figure 2B). Thus, while not quantitative, even at this level the CoMSIA model was able to make order of magnitude predictions, underscoring the reasonableness of the model and the underlying pharmacophore. In the study reported here, we focus on identifying the character of the hydrogen-acceptor group(s) 1 and/or 2 required for induction of apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Pharmacophoric model showing essential components of apoptosis-inducing activity used for the design of 3-Cl-AHPC and its analogues. (A) Three-dimensional seven-point pharmacophore descriptive of common elements in compounds in an AHPN analogue training set of which 44% were active at inducing MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell apoptosis at 1.0 µM after a 96-h treatment. Components 1 and 2, hydrogen-bond acceptor; 3, hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor; 4, hydrophobic ring; 5, hydrophobic group; 6, sterically accessible hydrophobic region; and 7, sterically accessible polar-permissible region. Interpoint distances (Å) ± SD: Δ(1–2), 2.1 ± 0.01; Δ(1–3), 12.5 ± 0.1; Δ(1–4), 5.9 ± 0.1; Δ(1–5), 12.4 ± 1.2; Δ(2–3), 12.5 ± 0.2; Δ(2–4), 5.7 ± 0.2; Δ(3–5), 4.0 ± 0.1; Δ(4–5), 7.5 ± 0.1; Δ(4–6) ≥ 2.3. (B) Comparative molecular similarity index analysis on 19 analogues using the overlap rule/ pharmacophore defined in (A) for prediction of induction of apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells after treatment for 96 h at 1.0 µM by comparing natural logs of experimental and calculated values. Predictive R2 = 0.78; uncross-validated R2 ± SE = 0.95 ± 0.45.

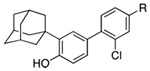

Replacement of the carboxylic acid group of 3-Cl-AHPC (5) by isosteric and other groups having a similar pattern of polar atoms that function as hydrogen-bond acceptors was explored to determine whether pharmacologic properties could be improved with retention of apoptotic activity. Our earlier studies indicated that shifting the position of the carboxylate group relative to the phenolic hydroxyl was not successful. No apoptosis of trans-RA-resistant HL-60R leukemia cells36 was observed after 24-h treatment with 1.0 µM 6-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-3-naphthalenecarboxylic acid (11 in Table 2), compared to 98% apoptosis with 1.0 µM AHPN (1). The 96-h treatment of retinoid-resistant MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells with 2.0 µM 5-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-1-naphthalenecarboxylic acid produced only 4% apoptosis, compared to 46% apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 cells induced by 1.0 µM 1. Replacement of the 2-carboxylate group with phenolic hydroxyl, carboxamide, and N-ethyl sulfonamide groups was similarly unsuccessful. Only 15% inhibition of primary human microvascular endothelial (HMVE) cell growth resulted on treatment with 1.0 µM 6-[3′-(1-adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-2-naphthol (12). The carboxamide derivative of 5-Me-AHPN (3) at 1.0 µM or 5.0 µM was essentially inactive at inducing retinoid-resistant KG-1 AML cell apoptosis at 48 h (3% and 5%, respectively, compared to 2% apoptosis in the vehicle-treated control) although 3 at 1.0 µM and 5.0 µM induced 51% and 73% apoptosis, respectively. After 48 h, KG-1 AML cell growth inhibition by the carboxamide derivative of 3 at 5.0 µM was 3% compared to 2% in the control and 96% in 5.0 µM 3-treated cells. Similar results were obtained after 72 h of treatment. Evidently, KG-1 cells were unable to cleave a primary amide to the active carboxylate. Apoptosis induced in MDA-MB-231 cells after a 96-h treatment with the 2-(N-ethyl sulfonamide) analogue of 1 at 2.0 µM was only 2%, although growth inhibition was 30%.

Table 2.

Comparison of Effects of 3-Cl-AHPC (5) and Its Analogues on HMVE Cell Proliferation after 96 h of Treatment Compared to trans-Retinoic Acid (7) and Synthetic RARγ-selective Analogues 13and 14

| compound | IC50(µM)a | inhibition (%) at 0.5 µMb |

|---|---|---|

| AHPN (1) | 0.3 | 70 |

| 5-Cl-AHPN (2) | 0.5 | 45 |

| AHPC (4) | 0.1 | 90 |

| 3-Cl-AHPC (5) | 0.3 | 60 |

| trans-RA (7) | >0.5c | 10 |

|

||

| AHPN-3-CO2H (11) X = H, Y = CO2H | >0.5c | 15 |

| AHPN-2-OH (12) X = OH, Y = H | >0.5c | 15 |

|

||

| 13 X = NHOH | >0.5c | 30 |

| 14 X = (SCH2)2 | >0.5c | 15 |

Concentration inhibiting proliferation by 50%.

Relative to vehicle alone control.

Highest concentration evaluated.

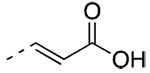

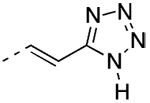

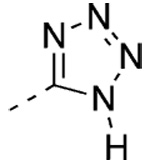

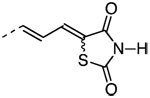

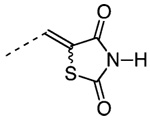

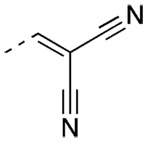

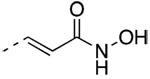

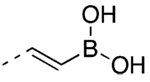

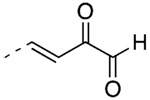

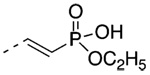

Because shifting the 2-carboxyl group of AHPN (1) to the 3-position and replacing the 2-carboxyl group by a hydroxyl group (11 and 12 in Table 2) were unpromising, other modifications were investigated using 3-Cl-AHPC (5) as the scaffold. The tetrazole and thiazolidinedione termini were investigated using analogues 24, 31, 39, and 43. These termini were reported to reduce retinoid activity by the Dawson32 and Shudo37,38 groups, respectively. The ability of nitriles (C=O bioisostere)39 and hydroxamates to function as hydrogen-bond acceptors led to the design of 45 and 48, respectively. The boronic acid and phosphonic acid monoethyl ester analogues (57 and 63, respectively) were also investigated. In the latter case, the monoester rather than the free acid was prepared to improve membrane permeability.

On the basis of our finding that commonly used carboxylate replacements (OH and CONH2) resulted in loss of apoptotic activity, we hypothesized that the carboxylate group of 3-Cl-AHPC (5) was crucial for bioactivity. Retinoid carboxylates are known to form strong salt bridges with the side-chain guanidinium groups of arginines in the ligand-binding pockets of RARs and RXRs. For example, the crystallographic structure of trans-RA (7) bound to the RARγ ligand-binding domain (PDB 2LBD) reveals a strong salt bridge between the carboxylate of 7 and the guanidinium group of Arg-278 located at the C-terminus of helix 5.40,41 We further hypothesized that a putative arginine in the receptor protein for 542 could interact with the carboxylate of 5. If this were correct, an analogue bearing a terminal 2-oxoaldehyde could undergo the Maillard reaction with the arginine guanadinium group or at least hydrogen-bond with this group. Methyl glyoxal and α-diones undergo the Maillard reaction with the arginine guanidinium group to form pyrimidines.43–45 2-Oxoaldehyde 60 was designed to test this hypothesis. The structures of these isosteric carboxylate analogues are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effects of 3-Cl-AHPC (5) and Analogues on Leukemia Cell Apoptosis and Leukemia and Cancer Cell Proliferation

|

KG-1 AML apoptosis (%)a | growth inhibition IC50 value (µM) (% inhibition at 1.0 µM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 5.0 | KG-1 | MDA-MB-231 | H292 | DU-145 | ||

| compound | R | µM | µM | AMLb | breastc | lungc | prostatec |

| 5 |  |

35 | 55 | 0.30 (44) | 1.8 (32) | 0.4(79) | 0.5(76) |

| 24 |  |

10 | 12 | 13d(0) | 21(0) | 16(3) | 14(0) |

| 31 |  |

2 | 2 | >5e(13) | 71(0) | 14(3) | 52(0) |

| 39 |  |

2 | 2 | >5f(0) | 24(0) | 23(2) | 15(0) |

| 43 |  |

8 | 10 | 14d(28) | 18(0) | 3.6(17) | 3.7(17) |

| 45 |  |

0 | 3 | >5e(0) | >10e(0) | >10e(0) | >10e(4) |

| 48 |  |

0 | 4 | >5e(0) | 6.3d(4) | 9.0d(6) | 3.5 (7) |

| 57 |  |

4 | 4 | >5e(0) | 19f(3) | 7.2(0) | 7.0(2) |

| 60 |  |

5 | 6 | 10d (11) | 14(0) | 7.0(7) | 7.8(0) |

| 63 |  |

0 | 0 | >5e(0) | >5.0e(3) | >5.0e(2) | >5.0e(3) |

Apoptosis after 48 h of treatment.

Inhibition of proliferation relative to vehicle-alone control after 48 h of treatment for KG-1 leukemia cells.

Inhibition of proliferation relative to vehicle-alone control after 72 h for solid tumor cell lines, with one media ± compound change after 48 h. At 5.0 µM, inhibition of KG-1 AML growth was as follows: 5, 67%; 24, 31%; 31, 21%; 39, 2%; 43, 41%; 45, 0%; 48, 0%; 57, 0%; 60, 38%; 63, 0%.

Extrapolated value; highest concentration evaluated was 5.0 µM.

Low activity at highest concentration evaluated (5.0 µM or 10 µM) did not permit extrapolation.

Extrapolated value; highest concentration evaluated was 10 µM.

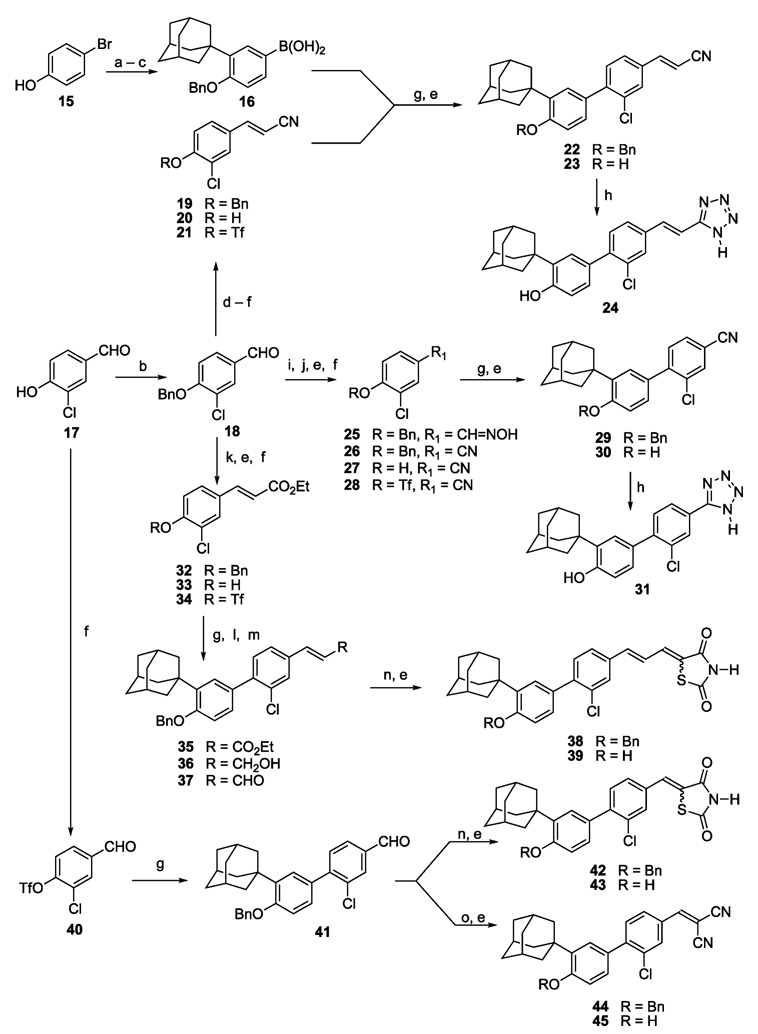

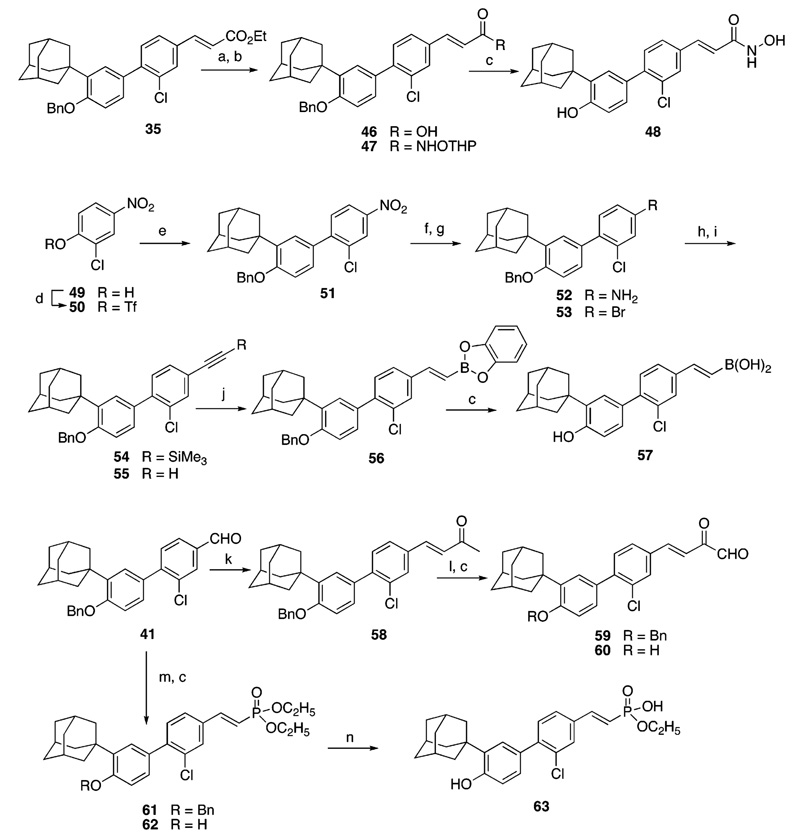

Synthesis

Routes to the 3-Cl-AHPC (5) analogues are shown in Scheme 1 and Scheme 2. Like 5, these analogues are characterized by a tetrasubstituted 1,1′-biphenyl core that was introduced by a Suzuki–Miyaura diaryl coupling reaction46 between the arylboronic acid 16 and a 4-substituted 2-chlorophenyl triflate (21, 28, 34, 40, or 50) using tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)-palladium as the catalyst generally in the presence of LiCl and an aqueous base in refluxing dimethoxyethane (Scheme 1 and Scheme 2). Coupling yields ranged from 51% to 91%. Intermediate 166 was prepared in three steps (74% overall yield), namely (i) Friedel–Crafts monoalkylation of 4-bromophenol (15) with 1-adamantanol catalyzed by methanesulfonic acid or concd sulfuric acid, which gave comparable yields of 2-(1-adamantyl)-4-bromophenol and no detectable diadamantylation product; (ii) protection of the phenolic hydroxyl group of the adamantylation product as the benzyl ether; and (iii) low-temperature (−78 °C) lithium–halogen exchange of resultant 3-(1-adamantyl)-4-benzyloxybromobenzene using n-butyllithium, conversion of the aryllithium to the arylboronate ester by treatment with tri-(isopropyl) borate, and acid hydrolysis during workup.

Scheme 1a.

a Reagents and conditions: (a) 1-AdOH, concd H2SO4, CH2Cl2. (b) PhCH2Br, K2CO3, acetone, reflux. (c) n-BuLi, −78 °C; B(Oi-Pr)3, −78 °C to room temperature; dil. HCl. (d) [(EtO)2P(O)CH2CN, KN(TMS)2, THF, −78 °C], −78 °C to room temperature. (e) BBr3, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; H3O+. (f) Tf2O, pyridine, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to room temperature. (g) 16, Pd(PPh3)4, 2 M Na2CO3, LiCl, DME, reflux. (h) Me3SiN3, (n-Bu)2SnO, PhMe, 90° to 95 °C. (i) NH2OH·HCl, MeOH, pyridine, 50 °C. (j) MeSO2Cl, PhMe, pyridine. (k) [(EtO)2P(O)CH2CO2Et, KN(TMS)2, THF, −78 °C], −78 °C to room temperature. (l) DIBAL, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; dil. HCl. (m) (COCl)2, Me2SO, NEt3. (n) 2,4-Thiazolidinedione, HOAc, NHEt2, PhMe, 50° to 60 °C. (o) CH2(CN)2, DMF, reflux.

Scheme 2a.

a Reagents and conditions: (a) LiOH·H2O, THF, H2O; dil. HCl. (b) H2NOTHP, DIC, DMAP, CHCl3, 0 °C to room temperature. (c) BBr3, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; H3O+. (d) Tf2O, pyridine, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to room temperature. (e) 16, Pd(PPh3)4, aq K3PO4, DME, reflux. (f) SnCl2•2 H2O, EtOH, reflux. (g) CuBr2, t-BuNO2, MeCN, 0 °C to room temperature. (h) Pd(PPh)3, CuI, Et3N, Me3Si-acetylene, reflux. (i) (n-Bu)4NF, THF. (j) Catecholborane, THF, reflux. (k) MeCOCH2P(Ph)3Br, 1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene, THF, room temperature to 70 °C. (l) H2SeO3, dioxane/H2O (10:1). (m) Tetraethyl methylenediphosphonate, 50% aq NaOH, CH2Cl2. (n) 20% aq HCl, reflux.

4-Hydroxyl-3-chlorobenzaldehyde (17) was used to generate four of the triflate intermediates (21, 28, 34, and 40) as shown in Scheme 1. In the case of the tetrazole-terminated targets 24 and 31 and the thiazolidendione-terminated target 39, the hydroxyl group of 17 was protected as the benzyl ether so that benzaldehyde 18 could be elongated to cinnamonitrile 19 and ethyl cinnamate 32 by olefination chemistry or be derivatized to the hydroxylimine 25 for dehydration to produce benzonitrile 26. The E isomer predominated in the olefination products 19 and 32 according to their 1H NMR spectra, which indicated about 5% of the Z isomer at most. The unwanted isomer was readily removed by chromatography. Low-temperature (−78 °C) cleavage of the benzyl ether protecting groups from 19, 26, and 32 using boron tribromide afforded phenols 20, 27, and 33. These phenols and 17 were converted to their respective triflates 21, 28, 34, and 40 using triflic anhydride and pyridine in dichloromethane. Diaryl coupling of the triflates with 16 introduced the substituted 1,1′-biphenyl scaffolds of intermediates 22, 29, 35, and 41, respectively.

After removal of the benzyl protecting groups from 22 and 29, the nitrile groups of their parent phenols 23 and 30 were allowed to undergo cycloaddition with trimethylsilyl azide in the presence of di(n-butyl)tin oxide47 to introduce the 5-substituted tetrazole termini of targets 24 and 31, respectively. The ethyl cinnamate, intermediate 35,35 was converted by hydride reduction followed by Swern oxidation48 to (E)-cinnamaldehyde 37, which was subjected to condensation/elimination with 2,4-thiazolidinedione to afford the 5-cinnamylidene-2,4-thiazolidinedinone 38. The substituted benzaldehyde, intermediate 41, was similarly transformed to the 5-benzylidene-2,4-thiazolidinedione 42. Thiazolidinedione formation produced both double-bond isomers. Their 1H NMR spectra indicated that the Z-double bond isomers 38 and 42 predominated as demonstrated by the downfield positions (0.4 ppm) of their vinylic protons trans to the sulfur atom (H−C=C−S) compared to those that were cis. Chromatographic purification and debenzylation of 38 and 42 afforded the 5-cinnamylidene- and 5-benzylidene-2,4-thiazolidinedione targets 39 and 43, respectively. Knoevenagel condensation of benzaldehyde 41 with malononitrile49 and debenzylation produced the 2-benzylidenepropanedinitrile 45. However, if 17 were first converted to the 2-(3′-chloro-4′-hydroxybenzylidene)propanedinitrile and then treated with triflic anhydride, the triflate ester was not obtained.

Syntheses of hydroxamic acid 48, boronic acid 57, 2-oxoaldehyde 60, and monoethyl phosphonate 63 are outlined in Scheme 2. Cinnamyl ester 35 from Scheme 1 was hydrolyzed to cinnamic acid 46,35 which was converted to the activated ester by treatment with diisopropylcarbodiimide and 4-di-methylaminopyridine. Reaction of this ester with the tetrahydropyranyl ether of hydroxylamine50 produced the protected hydroxamic acid 47. Concomitant low-temperature cleavage of the benzyl and tetrahydropyranyl protecting groups with boron tribromide afforded the hydroxamic acid target 48. Reaction of the activated ester of 3-Cl-AHPC (5) with hydroxylamine failed to produce 48 in the presence of the unprotected phenolic group.

Construction of the 2-arylethenylboronic acid 57 was accomplished in eight steps from 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol (49). Because aryl bromides and triflates typically undergo coupling with boronic acids with equal efficiency and the ortho chloro group in 49 was expected to hinder coupling by the aryl triflate, the bromo group was masked as a nitro group in triflate 50 to accomplish coupling with 16. The nitro group in the coupled product, 51, was then transformed to the bromo group by reduction to the amine and diazotization under hydrophobic conditions using tert-butyl nitrite in the presence of cupric bromide.51 Aryl bromide 53 underwent Sonagashira coupling with trimethylsilylacetylene52 to give the protected phenylacetylene 54. Desilylation of 54 with tetra(n-butyl)ammonium fluoride52 provided phenylacetylene 55. Benzodioxaborole 56 was prepared by the cis-hydroboration of 55 with catecholborane.53 Treatment of 56 with boron tribromide (−78 °C) cleaved both benzodioxa and benzyl protecting groups to produce the (E)-2-phenylethenyl boronic acid 57.

To prepare the 2-oxoketoaldehyde 60, we introduced the (E)-2-oxopropylidene group of 58 by olefination of benzaldehyde 416 with the ylid derived from (2-oxopropyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide.54 The aldehyde group of 59 was obtained by selenous acid oxidation55 of the methyl group of 58. Debenzylation of 59 afforded 60. Horner–Emmons–Wadsworth olefination of 41 using the anion of tetraethyl methylenediphosphonate56 produced diethyl phosphonate 61, which on acid hydrolysis57 and debenzylation with boron tribromide produced the monoethyl phosphonate 63.

Biological Activity

Of the compounds shown in Table 3, only 3-Cl-AHPC (5) efficiently induced KG-1 cell apoptosis after a 48-h treatment at 1.0 µM (30%) or 5.0 µM (55%). Its inhibition of cell growth was comparable (44% and 67%, respectively). After 96 h of treatment with 1.0 µM 5, apoptosis rose to 66% compared to 7% in the Me2SO-alone control. Evidently, the region of the target protein with which the carboxylate group of 5 interacts to mediate its apoptotic effects is sufficiently constrained to prevent the other hydrogen-acceptor groups in the analogues shown in Table 3 from efficient interaction. However, similar constraints did not appear to impact inhibition of proliferation as potently. Thus, tetrazoles 24 and 31 and thiazolidinedione 43 were modest inhibitors of KG-1 cell proliferation as measured by cell counting but induced minimal apoptosis (2%–10% compared to 2%–3% in the control). On the basis of its efficient overlap with 5 and structural similarity, we had predicted that tetrazole 24 would have significant antiproliferative and apoptotic activities and that the longer thiazolidine 39 would lack such activities. However, both proved to be inactive in the apoptosis induction assays, and 39 lacked antiproliferative activity. 2-Oxoaldehyde 60 was also unable to induce apoptosis but did show weak growth inhibition (38% at 5.0 µM). Recently, we demonstrated that 3-A-AHPC (6) antagonized 5-induced apoptosis but retained antiproliferative activity.6

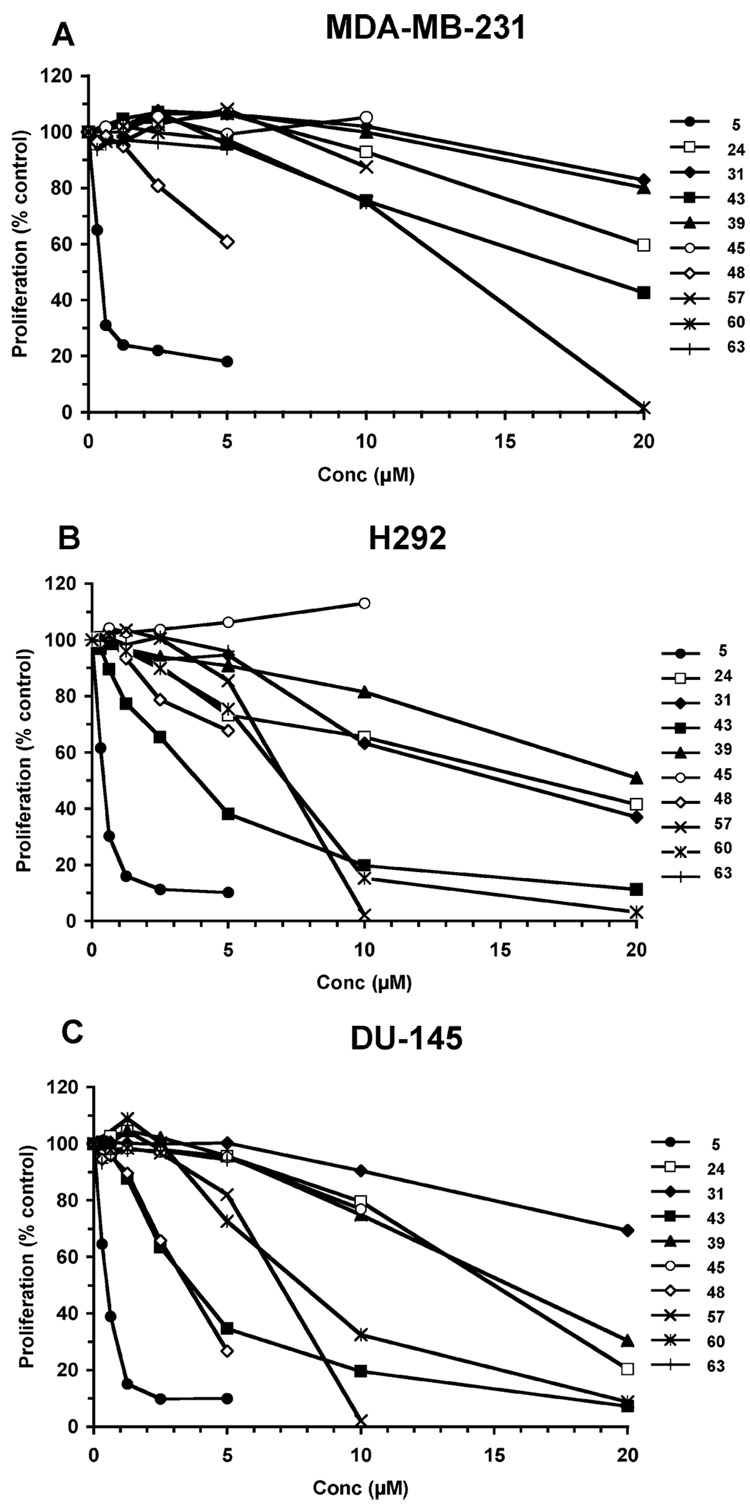

3-Cl-AHPC (5) and its analogues were also assessed for their abilities to inhibit the proliferation of retinoid-resistant MDA-MB-231 breast, H292 lung, and DU-145 prostate cancer cells grown in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum. Dose–response curves are shown in Figure 3. On the basis of their IC50 values (Table 3), H292 and DU-145 cells were generally more sensitive to inhibition under these growth conditions than MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 3). The most potent inhibitor in the series was 5. Thiazolidinedione 43 displayed modest growth inhibitory activity against the lung and prostate cancer cell lines (IC50 = 3.6 and 3.7 µM, respectively). Hydroxamic acid 48 displayed similar activity against prostate cancer cells (IC50 = 3.5 µM) and had an IC50 of about 6.3 µM (extrapolated value) against breast cancer cells. The other analogues were less active.

Figure 3.

Effects of 3-Cl-AHPC (5) and analogues 24, 31, 39, 43, 45, 48, 57, 60, and 63 on proliferation of trans-retinoic acid-refractory cancer cell lines after treatment for 72 h as described in the Experimental Section. (A) MDA-MB-231 breast cancer; (B) H292 lung cancer; and (C) DU-145 prostate cancer. Results shown are the averages of three replicates. Standard errors were below 10%

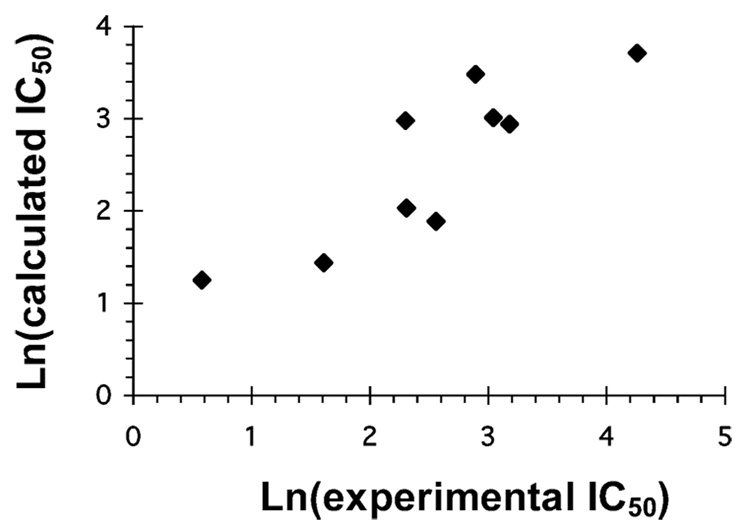

Most of the AHPN analogues in the original training set for apoptosis induction had a carboxyl group at the 2-position of the naphthalene ring. Modifying this group had a deleterious impact on apoptosis induction but not on inhibition of proliferation (Table 3). We next addressed the impact on KG-1 cell growth of variations in the position and character of the polar hydrogen-bond acceptor region (descriptive points 1 and 2 in Figure 2A) in an attempt to understand the biological data in terms of fundamental changes in the polar region. Thus, a fragment QSAR model was constructed using the isosteric polar/ hydrogen-bond acceptor replacements shown in Table 3 for the carboxyl group of 3-Cl-AHPC (5). While the number of analogues included in this portion of the SAR study was limited, a predictive fragment QSAR, ln(IC50 KG-1) = −2.65 + 0.121POLAR_V + 0.062 pKa (raw), having an R2 of 0.76 and a standard error of 0.78, using two independent variables could be developed and related to the ln(IC50) values.58 Polar volume (POLAR_V) and calculated (raw) pKa were the most important features influencing KG-1 growth inhibition. For the solid tumor cell lines, modestly predictive QSAR models (R2 = 0.5–0.8) were developed using the three properties of the longest length of the fragment (L), minimum in computed electrostatic potential on the van der Waals surface of the fragments (MINIM_PS) and polar volume. In Figure 4 is illustrated the quality of the three-parameter QSAR model for MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell growth inhibition IC50 values in terms of these properties. The resultant analysis had an R2 of 0.75 and a standard error of 0.6. The QSAR equation ln(IC50 MBA-MB-231) = 4.14 − 0.30L + 14.9MINIM_PS + 0.10POLAR_V with the ‘weights’ of the elements revealing their ‘relative contributions’. Analogously, analysis of the results on the other cell lines yielded similar equations: ln(IC50 H292) = 3.33 + 0.28L + 11.78MINIM_PS + 0.090POLAR_V with an R2 of 0.44 and a standard error of 1.1 and ln(IC50 DU-145) = 3.87 − 0.073L + 19.3MINIM_PS + 0.10POLAR_V with an R2 of 0.54 and a standard error of 1.0. While the predictive R2 values are only modest, the analyses do indicate that both the amount of polar atom (group) exposure and size are correlated with antiproliferative activity, whereas the other computed properties are not explanatory variables. Therefore, the analyses provide a preliminary indication of molecular design features coupled to growth inhibitory activity variations.

Figure 4.

Predictive fragment QSAR for isosteric replacements of hydrogen-bond acceptor region (components 1 and 2) in Figure 2 performed on 3-Cl-AHPC carboxylate and other polar termini shown in Table 3 and based on IC50 values for inhibition of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer proliferation after 96 h of treatment. The natural log of the antiproliferative activity in terms of IC50 values would be expressed as 4.14 − 0.30L + 14.9MINIM_PS + 0.10POLAR_V, where L is the longest length of the polar fragment; MINIM_PS is the minimum in the electrostatic potential on the van der Waals surface; and POLAR_V is volume of polar group, R2 ± SE = 0.75 ± 0.6.

The NR4A1 nuclear receptor protein was found to interact in the cytoplasm with the mitochondrial protein Bcl-2 to induce cancer cell apoptosis.59 The translocation of NR4A1 from nucleus to cytoplasm was observed to occur in several cancer cell lines after their transfer to media lacking serum and treatment with an analogue of AHPN (1). Once in the cytoplasm, NR4A1 was able to induce a proapoptotic conformational change in antiapoptotic Bcl-2 that led to mitochondrial cytochrome c release followed by apoptosis. Therefore, we attempted to correlate the sensitivity of MDA-MB-231 breast, H292 lung, and DU-145 prostate cancer cells to apoptosis induction by 3-Cl-AHPC (5) with their levels of NR4A1 (human TR3) protein expression. In lysates obtained from these cancer cell lines that had been both grown and treated with 1.0 µM 5 in media containing 10% fetal bovine serum we were not able to detect NR4A1 protein by Western blotting (data not shown). These results suggest that serum constituents could influence NR4A1 expression.

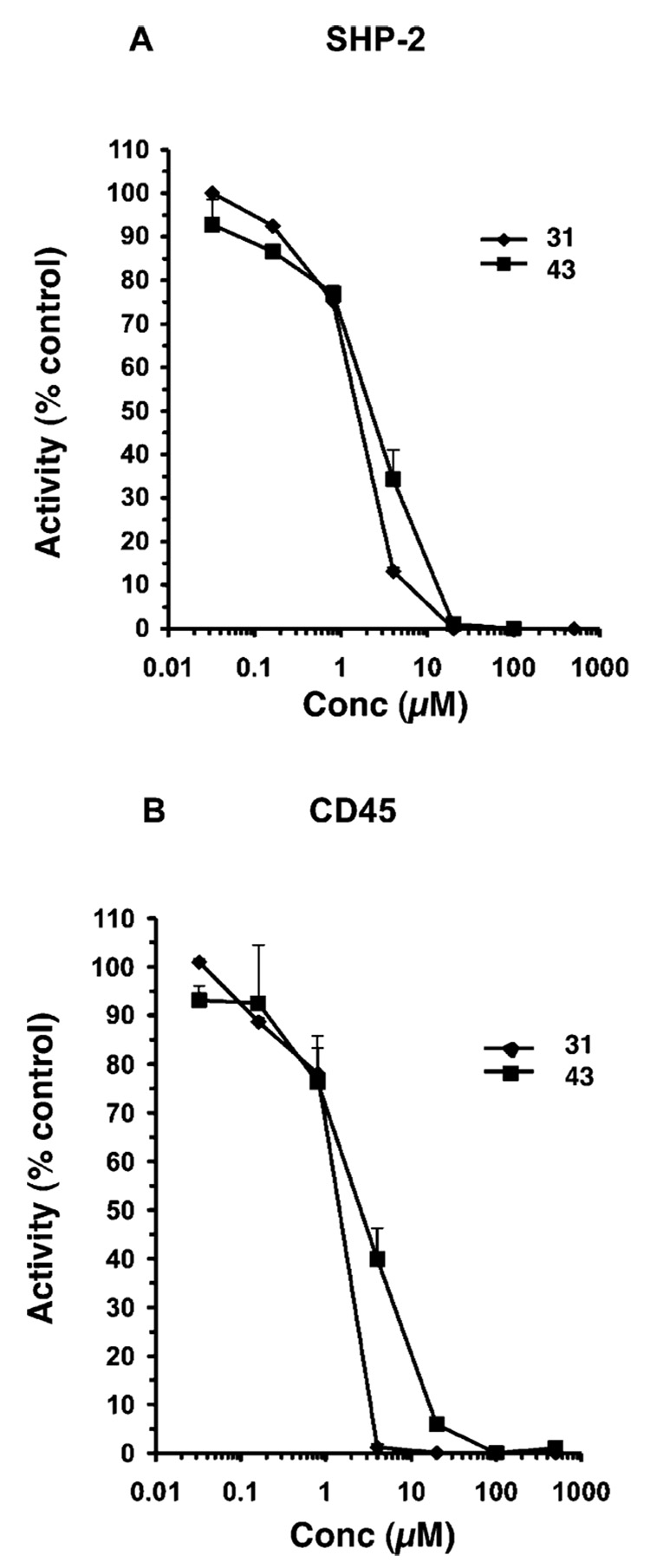

After Zhang et al.60 found evidence to suggest that AHPN (1) modulated enzyme activity on the basis of (i) its rapid induction of cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis; (ii) its lack of a requirement for gene transcription or protein synthesis as evidenced by resistance to actinomycin D or cycloheximide treatment, respectively, and (iii) its ability to inhibit the phosphohatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3-K)/Akt pathway, we hypothesized that the effects of 1 as well as those of 5-Cl-AHPN (2) and 3-Cl-AHPC (5) could be due to inhibition of an enzyme. Pfahl and Piedrafita subsequently reported that the IC50 value obtained for 1 in inhibiting the dual-specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase (MKP)-1 in vitro was in the 6-µM range.61 Because of their report, we investigated the inhibitory activity of several analogues of 5 on the protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) SHP-2 and CD45, both of which are implicated in the development of some forms of leukemia. Somatic gain-of-function mutations were found to occur in the PTPN11 gene for the cytoplasmic Src-homology 2 domain-containing PTP (SHP-2) in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and lead to hyperactivation of oncogenic Ras.62,63 Phosphorylated (activated) SHP-2 was reported to be overexpressed in 23 of 25 peripheral blood or bone marrow samples from adult chronic myeloid myelocytic leukemia patients but was only poorly or not expressed in samples from normal adults.64 In addition, SHP-2 was observed to coimmunoprecipitate with phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3-K) in BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase-transformed cells.65 In earlier work, we had observed that 5 was able to inhibit the PI3-K/Akt pathway in cancer cells.66 The KG-1 leukemia cell line is reported to express SHP-2.64 These observations suggested that inhibition of SHP-2 activity could affect KG-1 cell function and prompted us to investigate the effects of 5, 31, and 43 on KG-1 cells. Both 31 and 43 were found to inhibit SHP-2 PTP activity (Figure 5A) with IC50 values of 1.3 µM and 2.2 µM, respectively, and, therefore, could serve as leads for the development of more potent and selective inhibitors of this enzyme. The IC50 value for 5 was found to be 2.1 µM. This small sample did not permit us to correlate KG-1 growth inhibition with inhibition of enzyme activity.

Figure 5.

3-Cl-AHPC analogues 31 and 43 inhibit the activity of SHP-2 and CD45 protein tyrosine phosphatases in cleaving 6,8-difluoro-4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate (100 µM) as measured by fluorescence spectrometry of the cleavage product as described in the Experimental Section. SHP-2 and CD45 concentrations were 5 nM and 1 nM, respectively. Tetrazole 31, solid diamond; thiazolidinedione 43, solid square. Results shown are the average of duplicates ± SE.

CD45 PTP is found on the surface of cells of lymphohematopoietic lineage, including leukemia cells,67 and the expression of its isoforms is altered in acute myeloid leukemia.67,68 We observed that AHPC (4), 31, and 43 at 10 µM inhibited CD45 activity by 84%, 46%, and 53%, respectively, when dimethylformamide was used as the vehicle. 3-Cl-AHPC (5) and 60 were not evaluated. However, because 45, 48, and 57 had similar CD45 inhibitory activities (68%, 37%, and 54%, respectively) under these same conditions but at 5 µM were not able to inhibit KG-1 cell proliferation, the probability that 4, 31, and 43 inhibit KG-1 proliferation by inhibiting CD45 activity appears to be very low. As shown in the dose–response curve of Figure 5B, IC50 values for CD45 PTP activity inhibition by 31 and 43 were 1.2 µM and 2.3 µM, respectively, when dimethyl sulfoxide was used as the vehicle.

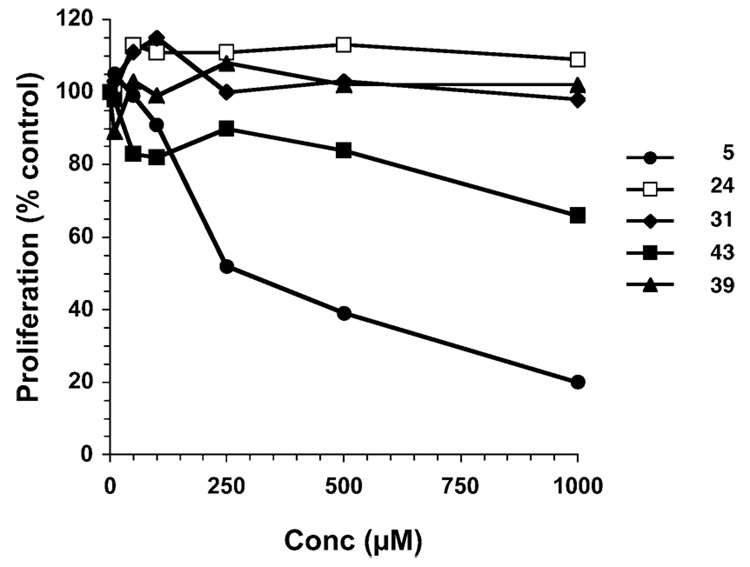

Cancer cells stimulate angiogenesis to promote tumor growth and metastasis. In the presence of growth factors released by tumors and their related stroma, human microvascular endothelial (HMVE) cells from the surrounding vasculature are induced to proliferate, migrate into the tumor, and assemble into microtubular vessels. Because cancer cells underwent both cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to 3-Cl-AHPC (5) and 5-Cl-AHPN (2), we wondered whether proliferating primary HMVE cells would behave similarly in culture. As shown in Figure 6, 5 effectively reduced HMVE cell growth (IC50 = 0.3 µM). Thiazolidinedione 43 had low inhibitory activity (30% inhibition at 1.0 µM), whereas 24, 31, and 39 had no significant effect on HMVE cell growth compared to that of the vehicle-treated control.

Figure 6.

3-Cl-AHPC (5) inhibits HMVE cell proliferation, whereas 43 is a poor inhibitor and 24, 31, and 39 do not inhibit. Cells were treated for 72 h at the indicated compound concentrations or with vehicle alone (Me2SO), detached by trypsinization and counted as described in the Experimental Section. A representative experiment is shown with proliferation expressed as the percent of vehicle alone-treated control.

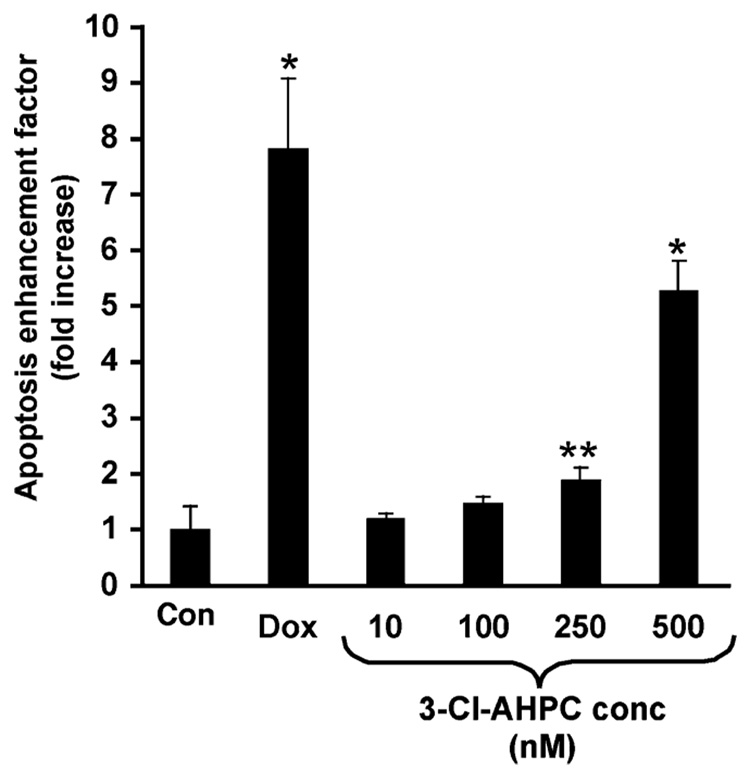

We next examined whether 3-Cl-AHPC (5) would induce the apoptosis of proliferating HMVE cells in culture. Although no obvious cell detachment or rounding was observed after a 20-h incubation with 5, oligonucleosome levels were significantly enhanced after treatment with 0.25 or 0.50 µM 5 in a concentration-dependent manner, as shown in Figure 7. These results demonstrate that 5 is able to induce HMVE cell apoptosis. Apoptosis induced by 0.5 µM 5 was 64% of that induced by 1.0 µM adriamycin. These results suggest that 5 has potential in vivo antiangiogenic activity.

Figure 7.

3-Cl-AHPC (5) induces apoptosis of HMVE cells. Cells were incubated for 20 h in the presence of Me2SO (negative control), positive control doxorubicin (1.0 µM), or 5 (10 nM to 500 nM) and assayed for apoptosis using a cell death detection ELISA as described in the the Experimental Section. Values represent the enrichment of mono- and oligonucleosome levels in treated sample relative to Me2SO control, and each bar represents the mean ± SD. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) compared with Me2SO control are indicated (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001).

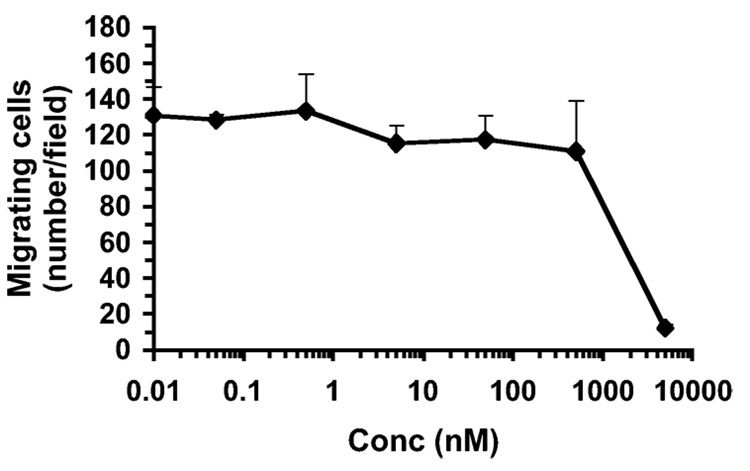

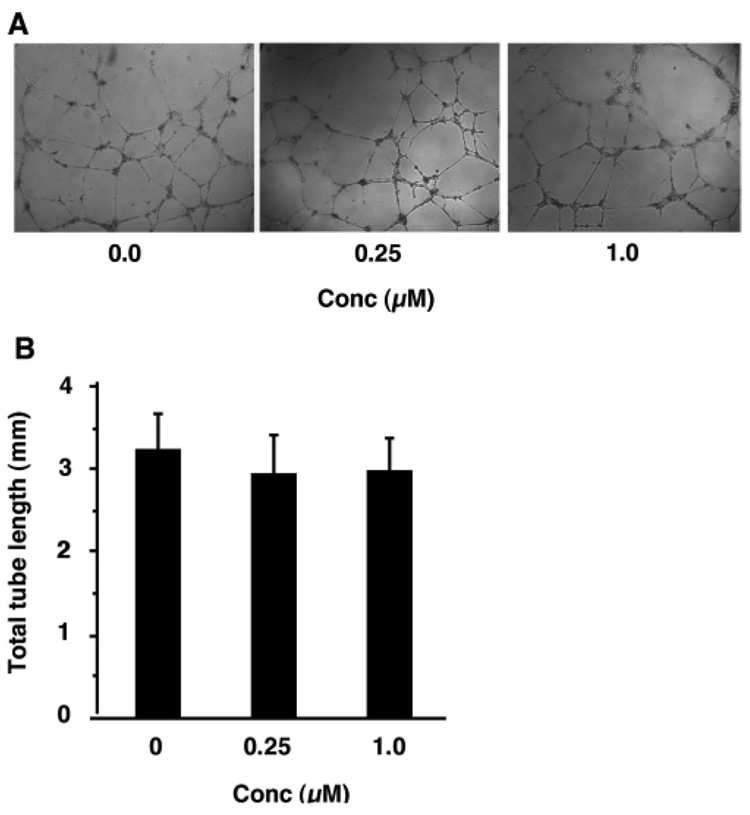

3-Cl-AHPC (5) was further examined for its effects on HMVE cell migration and tubule formation. As shown in Figure 8, 0.05 nM to 0.50 µM 5 had no statistically significant effect on cell migration through Matrigel when cells were treated for 5-h compared to cells treated with only vehicle. Moreover, 18-h treatment with 0.25 µM or 1.0 µM 5 had no statistically significant effects on either the level of tube formation or tube length in Matrigel by cells obtained from 80% confluent cultures (Figure 9). In contrast, trans-RA (7) and other classical retinoids are reported to inhibit angiogenesis in chick chorioallantoic membrane.69 To establish that these compounds were not exerting their effects through any retinoid-mediated pathway, the antiproliferative activity of AHPN (1) was compared to those of trans-RA (7), RARγ-selective transcriptional agonist SR11254 (13),70,71 and RARγ-selective antagonist SR11253 (14)70,71 in HMVE cells. The results shown in Table 2 demonstrate that 1 was the most potent of the four compounds, although it was less efficient as a transactivator of the RARs than 7.1 5-Cl-AHPN (2), AHPC (4), and 5 were also able to inhibit the proliferation of HMVE cells. In contrast, the 3-naphthalenecarboxylic acid and 2-naphthol analogues (11 and 12) of 1 were poor inhibitors of HMVE cell proliferation, just as they were of cancer cell growth.

Figure 8.

3-Cl-AHPC (5) does not inhibit HMVE cell migration. Migration through Matrigel was measured after 5-h incubation with the indicated concentrations of 5 or with vehicle alone as described in the Experimental Section. Results shown represent the mean number of cells ± SD of three fields in three replicates examined microscopically.

Figure 9.

3-Cl-AHPC (5) does not inhibit HMVE cell tubule formation or affect tube length. Cells in medium were layered onto Matrigel containing 0.25 µM or 1.0 µM 5, which was added as a Me2SO solution, or Me2SO alone. Tube formation was examined microscopically as described in the Experimental Section. (A) Results shown are representative of one field of four in triplicate experiments. (B) Total tube length was determined in four random fields for each triplicate experiment. Bars represent the means ± SD.

Recently, we discovered that 3-Cl-AHPC (5) binds to the small heterodimer partner (SHP) nuclear orphan receptor.14 Interestingly, prior to its inducing the intrinsic apoptosis cascade in KG-1 AML and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, 5 was found to interact with SHP in the nuclear Sin3A repressor complex. A recombinantly expressed glutathione S-transferase–SHP chimeric protein (GST–SHP) also bound 5, as evidenced by its ability to displace tritiated AHPN42 from GST–SHP bound to glutathione-linked Sepharose beads, as did AHPN (1) and the 3-chlorophenyltetrazole and 3-chlorobenzylidenethiazolidinedione analogues (39 and 43, respectively). The relative competitive displacement efficiencies of the tritiated label were as follows: nonlabeled 1, 53%; 5, 87%; 3-A-AHPC (6), 72%; tetrazole 39, 69%; thiazolidinedione 43, 37%; hydroxamic acid 48, 7%; and boronic acid 57, 0% at 50 µM.

Conclusion

Thus, 3-Cl-AHPC (5) appears to negatively impact cancer cell growth through two signaling pathways, namely inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis. Our results suggest that 5 also has antiangiogenic activity by modulating the same pathways in tumor microvasculature. The present fragment-based QSAR study on the hydrogen bond-accepting elements 1 and 2 of the pharmacophoric model shown in Figure 2A indicates that the dimensions of the elements and their minima in computed electrostatic potential on the van der Waals surface of the fragments have a major role in determining growth inhibitory activity. Defining the apoptotic activity properties of these elements was not possible because the present isosteric modifications of the carboxylate group abrogated apoptosis induction. These results suggest that if interaction with SHP regulates apoptotic activity, the region of SHP to which the carboxylate group binds is sterically constrained. Of the three hydrogen-acceptor analogues (5, 31, and 43) evaluated as inhibitors of phosphatases, only 5 was a potent inhibitor of both apoptosis and cell growth. Analogues 31 and 43 were only modest inhibitors of cell proliferation. Thus, while the present results suggest that inhibition of phosphatase activity may have a role in inhibition of cell proliferation, further studies will be necessary before robust conclusions can be drawn.

As observed with 3-A-AHPC (6), tetrazole 39 was able to compete with radiolabeled AHPN for binding to recombinantly expressed small heterodimer partner protein14 but was unable to induce KG-1 AML cell apoptosis. Earlier, we found that 6 was able to attenuate apoptosis induced by 3-Cl-AHPC (5).6 These results suggest that both 6 and 39 can function as antagonists of the apoptotic activity of 5. Thus, with identified potent agonists (1 and 5) and antagonists (6 and 39) of SHP–Sin3A-mediated apoptotic activity, we plan on pursuing our studies on how these compounds regulate transcriptional signaling through SHP. Because both 31 and 43 exhibited similar modest antiproliferative activities but had very low apoptosis-inducing activity, they may have application as probes of the pathway by which 5 induces cell-cycle arrest independent of apoptosis.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

Chemicals and solvents from commercial sources were used without further purification unless specified. Abbreviations for solvents and reagents are as follows: DIBAL, diisobutylaluminum hydride; DIC, diisopropylcarbodiimide; DMAP, 4-(N,N-dimethylamino)pyridine; DMF, dimethylformamide; DME, ethylene glycol dimethyl ether; TBAF, tetra(n-butyl)ammonium fluoride; THF, tetrahydrofuran; Tf2O, trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride. Reactions were carried out under argon and monitored by thin-layer chromatography on silica gel (mesh size 60, F254) with visualization under UV light. Organic extracts were dried over Na2-SO4 unless otherwise specified and concentrated at reduced pressure. Standard and flash column chromatography employed silica gel (Merck 60, 230–400 mesh). Experimental procedures were not optimized. Melting points for samples were determined in capillaries using a Mel-Temp II apparatus and are uncorrected. Infrared spectra were obtained using an FT-IR Mason satellite spectrophotometer on powdered samples. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a 300-MHz Varian Unity Inova spectrometer, and shift values are expressed in ppm (δ) relative to CHCl3 as an internal standard. Unless mentioned otherwise, compounds were dissolved in 2HCCl3. MALDI-FAB mass spectra were run on an Applied Biosystems Voyager De-Pro MALDI-TOF instrument at the Burnham Institute. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on an Agilent ESI-TOF mass spectrometer at The Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, CA). Electrospray mass spectrometry was performed on an ABI EPI-3000 instrument.

3-(1-Adamantyl)-4-benzyloxyphenylboronic Acid (16).35

Our reported procedure8 was adapted. To a solution of 3-(1-adamantyl)-4-benzyloxyphenyl bromide8 (2.00 g, 5.04 mmol) in THF (7 mL) at −78 °C (dry ice/acetone bath) under argon was added in one portion 1.6 M n-BuLi (7.56 mmol) in hexane (4.7 mL). The mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 15 min, (i-PrO)3B (3.5 mL, 15.1 mmol) was added, and the resulting solution was stirred at −78 °C for 20 min and then at room temperature overnight. The mixture was quenched with 0.1 N HCl (30 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 190 mL). The extracts were washed (brine) and dried. The residue after concentration was purified on silica gel (40% EtOAc/hexane) to give 1.63 g (89%) of 16 as a white solid, mp 151–153 °C. 1H NMR δ 1.78 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.09 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.27 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 5.23 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.07 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.33–7.55 (m, 5H, ArH), 8.04 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 8.2 ppm (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH).

4-Benzyloxy-3-chlorobenzaldehyde (18).72

To a suspension of 17 (4.68 g, 30 mmol) and K2CO3 (6.90 g, 50 mmol) in THF (50 mL) and DMF (10 mL) under argon was added benzyl bromide (6.84 g, 40 mmol). The mixture was heated at reflux for overnight, concentrated, diluted with CH2Cl2 (100 mL), washed (water, 1 N HCl and brine), and dried. Concentration and chromatography (15% EtOAc/hexane) afforded 6.22 g (84%) of 18 as a white solid; mp 92–94 °C. IR (CHCl3) 2966, 1682 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 5.23 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.08 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.35–7.46 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.74 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.94 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH), 9.85 ppm (s, 1H, CHO).

(E)-4-Benzyloxy-3-chlorocinnamonitrile (19)

To diethyl (cyanomethyl)phosphonate (885 mg, 5.0 mmol) in THF (5 mL) stirred with cooling in a dry ice/acetone bath was added under argon 10 mL of 0.5 M KN(SiMe3)2 (5.0 mmol) in toluene. Stirring was continued for 0.5 h before 1872 (738 mg, 3.0 mmol) in THF (5.0 mL) was slowly added over a 0.5-h period. After being stirred for 1 h more, the mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature, stirred overnight, poured into 1 M NH4Cl (10 mL) and water (20 mL), and extracted with hexane (100 mL). The extract was washed (water and brine) and dried. Concentration and chromatography on silica gel (EtOAc/hexane) afforded 710 mg (91%) of 19 as a white powder, Rf 0.47 (EtOAc/hexane); mp 110–114 °C. IR (CHCl3) 2966, 2215 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 5.21 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 5.73 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, HC=CCN), 6.97 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.26 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H, C=CHCN), 7.36–7.45 (m, 6H, ArH, 6-ArH), 7.51 ppm (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH). The crude nitrile was converted directly to 20.

General Procedure for Debenzylation of 19, 22, 26, 29, 32, 38, 42, 44, 47, 56, 59, and 61

To a stirred mixture of the benzyl ether (2.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) at −78 °C under argon was added slowly over a 10-min period 6.0 mL of 1.0 M BBr3 (6.0 mmol) in CH2Cl2. The mixture was stirred for 2 h at −78 °C. Water (10 mL) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 10 min and then extracted (EtOAc). The extract was washed (water and brine), dried, and concentrated. Flash chromatography of the residue on silica gel (10% EtOAc/hexane) yielded the phenol.

(E)-3-Chloro-4-hydroxycinnamonitrile (20)

19 (672 mg, 2.5 mmol) yielded 420 mg (94%) of 20 as a pale-yellow powder, Rf 0.12 (10% EtOAc/hexane); mp 165–169 °C. IR (powder) 3416, 2966, 2213 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 6.32 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, HC=CHCN), 7.02 (dd, J = 3.0, 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.48 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.54 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, HC=CHCN), 7.75 (s, 1H, 2-ArH), 10.88 ppm (s, 1H, OH). The crude product was converted directly to the triflate 21.

(E)-4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamonitrile (23)

22 (420 mg, 87 mmol) yielded 310 mg (87%) of 23 as a pale-yellow solid, Rf 0.15 (5% EtOAc/hexane); mp 142–148 °C, which was used to prepare 24. IR (CHCl3) 3394, 2906, 2226, 1284 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.80 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.10 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.16 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 5.00 (s, 1H, OH), 5.90 (d, J = 17.1 Hz, 1H, HC=CHCN), 6.72 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.17 (dd, J = 2.1, 8.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.32 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.33 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCN), 7.38 (s, 1H, 2′-Ar), 7.39 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.55 ppm (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, 3-ArH).

3-Chloro-4-hydroxybenzonitrile (27)

26 (850 mg, 3.5 mmol) yielded after chromatography (20% EtOAc/hexane) (470 mg, 88%) of phenol 27 as a pale-yellow solid, which was converted directly to triflate 28.

4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-3-chlorobenzonitrile (30)

29 (300 mg, 0.66 mmol) yielded 0.45 g (87%) of 30 as a pale-yellow solid, Rf 0.37 (10% EtOAc/hexane); mp 220–222 °C. IR (CHCl3) 3410, 2966, 2237, 1278 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.80 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.10 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.15 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 5.02 (s, 1H, OH), 6.74 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.17 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.30 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.44 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.57 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.75 ppm (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH). FTMS (HRMS) calcd C23H23-ClNO [M + H]+ expected 364.1463, found 364.1461.

Ethyl (E)-3-Chloro-4-hydroxycinnamate (33).8

3272 yielded after chromatography (24% EtOAc/hexane) 0.855 g (92%) of 33 as a white solid, mp 106–108 °C. 1H NMR δ 1.34 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH2CH3), 4.26 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, CH2CH3), 5.84 (s, 1H, OH), 6.32 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO), 7.04 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.52 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH), 7.58 ppm (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO). The product was used directly in the next step.

5-[3-(3′-(1-Adamantyl)-2-chloro-4′-hydroxy-4-biphenyl)-(2E)-2-propenylidene]-2,4-thiazolidinedione (39)

38 (35 mg, 0.06 mmol) yielded 25 mg (85%) of 39 as an orange powder, Rf 0.27 (30% EtOAc/hexane); mp 162–164 °C (dec). IR (CHCl3) 3394, 2912, 1695, 1601, 1278 cm−1; 1H NMR (C2H3O2H) δ 1.78 (s, 6H, AdCH2). 2.07 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.17 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 6.80 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 6.91 (dd, J = 15.9, 11.4 Hz, 1H, ArCH= CHCH=C), 7.12 (dd, J = 7.8, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.16 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H, ArCH=CHCH=C), 7.26 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.38 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.52 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H, ArCH= CHCH=C), 7.58 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.70 ppm (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH). HRMS calcd C28H26ClNO3S [M − H]− 490.1249, found 490.1245.

5-{4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-3-chlorobenzylidene}-2,4-thiazolidinedione (43)

42 (12 mg, 0.02 mmol) yielded after chromatography (20% EtOAc/hexane) 8.3 mg (91%) of 43 as a yellow powder, Rf 0.36 (20% EtOAc/hexane); mp 280–284 °C. IR (CHCl3) 3372, 2902, 1655, 1577 cm−1; 1H NMR (C2H3O2H) δ 1.85 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.08 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.22 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 6H, AdCH2), 6.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.16 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.28 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.50 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.55 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.68 (s, 1H, 2-ArH), 7.80 ppm (s, 1H, ArCH=C). HRMS calcd C26H24ClNO3S [M − H]− 464.1093, found 464.1107.

2-{[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-2-chloro-4′-hydroxy-4-biphenyl]methylene}-propanedinitrile (45)

44 (74 mg, 0.15 mmol) yielded after chromatography (20% EtOAc/hexane) 42.5 mg (70%) of 45 as a yellow solid, mp 225–226 °C. IR 3450, 2901, 2848, 2230, 1276 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.80 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.11 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.15 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 5.08 (s, 1H, OH), 6.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.24 (dd, J = 7.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.36 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.53 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 2 ′-ArH), 7.74 (s, 1H, CH=C(CN)2), 7.90–7.94 ppm (m, 2H, 3-ArH, 6-ArH). HRMS calcd C26H23ClN2O [M − H]− 413.1426, found 413.1418.

N-(Hydroxy)(E)-4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-hydroxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamamide (48)

47 (70 mg, 0.117 mmol) yielded after chromatography (HOAc/EtOAc/hexane, 0.3:10:10) 22 mg (45%) of 48 as a pale-tan solid, mp 208 °C (dec). IR 3334, 2899, 1652, 1382 cm−1; 1H NMR [(C2H3)2SO] δ 1.75 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.04 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.16 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 6.65 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO), 6.88 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.12 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.16 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.41 (s, 1H, 3-ArH), 7.50 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO), 7.55 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.71 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 9.63 (bs,1H, OH), 9.69 (bs, 1H, N HOH), 10.81 ppm (bs, 1H, NHO H). HRMS calcd C25H26ClNO3 [M + H]+ 424.1674, found 424.1669.

(E)-2-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-2-chloro-4′-hydroxy-4-biphenyl] - ethenylboronic Acid (57)

56 (56 mg, 0.097 mmol) yielded after chromatography (50% EtOAc/hexane) 31 mg (67%) of 57 as a paletan solid, mp 186–189 °C. IR 3350, 2901, 1621, 1217 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.81 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.11 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.18 (m, 6H, AdCH2), 4.92 (s, 1H, OH), 6.38 (d, J = 18 Hz, 1H, CH=CHB), 6.74 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.22 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.36 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.39 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.55 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.73 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 3-ArH), 7.76 ppm (d, J = 18 Hz, 1H, CH=CHB). HRMS calcd C24H26BClO3 [M + H]+ 409.1736, found 409.1730.

(3E)-4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-2-chloro-4′-hydroxy-4-biphenyl]-2-oxobut-3-enal (60)

59 (35 mg, 0.068 mmol) yielded after chromatography (25% to 33% EtOAc/hexane) 22 mg (77%) of 60 as a yellow wax, mp 121–123 °C. IR 3383, 2902, 1695, 1678, 1603, 1251 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.80 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.11 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.16 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 5.10 (s, 1H, OH), 6.74 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 6.97 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO), 7.20 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.34 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.41 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.52 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.71 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 3-ArH), 7.80 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO), 9.47 ppm (s, 1H, CHO). HRMS calcd C26H25ClO3 [M + H]+ 421.1565, found 421.1573.

Diethyl (E)-2-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-2-chloro-4′-hydroxy-4-biphenyl]ethenylphosphonate (62)

61 (0.14 mmol, 82 mg) yielded after chromatography (50% to 67% EtOAc/hexane) 61 mg (87%) of 62 as an off-white solid, mp 110–112 °C. IR 3414, 2932, 1028, 989 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.38 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H, OCH2CH3), 1.79 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.09 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.17 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 4.18 (m, 4H, OCH2CH3), 6.29 (t, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H, CH=CHP), 6.82 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.17 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.31 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.33–7.41 (m, 3H, 5-ArH, 6-ArH, OH), 7.48 (dd, J = 17.4, 22.5 Hz, 1H, CH=CHP), 7.59 ppm (s, 1H, 3-ArH). HRMS calcd C28H34ClO4P [M + H]+ 501.1956, found 501.1958.

General Procedure for Converting Phenols 20, 27, 33, 17, and 49 to Their Triflates

To a stirred solution of the phenol (2.0 mmol) in pyridine (5 mL) at 0 °C (ice-bath) under argon was slowly added Tf2O (846 mg, 3.0 mmol) over a 0.5-h period. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then extracted (EtOAc). The extract was washed (10% HCl, 5% NaHCO3, brine and water), dried, and concentrated to afford an oil, which was purified by chromatography (5% EtOAc/hexane) to give the triflate.

(E)-3-(3-Chloro-4-trifluoromethanesulfonyloxy)cinnamonitrile (21)

20 (358 mg, 2.0 mmol) gave 565 mg (91%) of 21 as a white powder, Rf 0.68 (10% EtOAc/hexane); mp 93– 99 °C. IR (CHCl3) 2966, 2226 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 5.93 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H, HC=CHCN), 7.34 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H, HC=CHCN), 7.42 (s, 2H, 5,6-ArH), 7.62 ppm (s, 1H, 2-ArH). The crude product was used to prepare 22.

3-Chloro-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyloxy)benzonitrile (28)

Crude 27 (306 mg, 2.0 mmol) gave 530 mg (93%) of 28 as a white powder, Rf 0.80 (20% EtOAc/hexane); mp 55–56 °C, which was used directly for coupling to produce 29. IR (CHCl3) 2961, 2243 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 7.50 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.69 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.86 ppm (s, 1H, 2-ArH).

Ethyl (E)-3-Chloro-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyloxy)cinnamate (34).8

33 (800 mg, 3.54 mmol) gave 1.13 g (93%) of 34 as a white solid, Rf 0.62 (10% EtOAc/hexane); mp 78–80 °C. IR (CHCl3) 2961, 1706, 1651, 1432 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.35 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 4.29 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 6.44 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, HC=CHCO), 7.39 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5ArH), 7.48 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.60 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO), 7.68 ppm (s, 1H, 2-ArH). HRMS calcd C12H10ClF3O5S [M + H]+ 358.9962, found 358.9951.

3-Chloro-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyloxy)benzaldehyde (40)

17 (1.56 g, 10.0 mmol) gave 2.30 g (79%) of 40 as a pale-yellow oil, Rf 0.65 (20% EtOAc/hexane). IR (CHCl3) 2961, 1717, 1223 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 7.61 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.94 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 6ArH), 8.11 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH), 10.07 ppm (s, 1H, CHO). FTMS (HRMS) calcd C8H5ClF3O4S [M+ H]+ expected 288.9544, found 288.9542.

2-Chloro-4-nitrophenyl Trifluoromethanesulfonate (50)

49 (1.58 g, 9.12 mmol) gave after chromatography (12.5% EtOAc/hexane) 2.73 g (97%) of 50 as a yellow oil, which was used to prepare 51. 1H NMR δ 7.59 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 8.26 (dd, J = 9, 2.7 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 8.45 ppm (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H, 3-ArH).

General Procedure for the Coupling between Aryl Boronic Acid 16 and Aryl Triflates 21, 28, 34, 40, and 50

To a stirred suspension of the aryl triflate (1.6 mmol), 16 (651 mg, 1.8 mmol), Pd(PPh3)4 (115 mg, 0.1 mmol), and LiCl (242 mg, 2.8 mmol) in DME (8 mL) was added under argon 1.3 mL of 2.0 M aq Na2CO3 (2.6 mmol). The mixture was heated at reflux for 24 h, cooled, and extracted (EtOAc). The extract was washed (water and brine), dried, and concentrated. Flash chromatography on silica gel (5% EtOAc/hexane) yielded the diaryl-coupling product.

(E)-3-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamonitrile (22)

21 (498 mg, 1.6 mmol) yielded 510 mg (64%) of 22 as a white solid, Rf 0.55 (5% EtOAc/hexane); mp 72–74 °C. IR (CHCl3) 2906, 2221 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.75 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.06 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.20 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 5.18 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 5.91 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCN), 7.02 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5′- ArH), 7.28 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.45–7.35 (m, 7H, ArH, 5-ArH, 2′-ArH), 7.48 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCN), 7.53 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.56 ppm (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 3-ArH). The crude product was used to prepare 23.

4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl]-3-chlorobenzonitrile (29)

28 (428 mg, 1.5 mmol) yielded 390 mg (57%) of 29 as a white solid, Rf 0.55 (5% EtOAc/hexane); mp 60–62 °C, which was used to prepare 30. IR (CHCl3) 2906, 2232 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.74 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.18 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 5.18 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.02 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.27 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.35–7.47 (m, 6H, 2′-ArH, ArH), 7.51 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.58 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.76 ppm (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH).

Ethyl (E)-4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamate (35).8

34 (500 mg, 1.40 mmol) yielded 1.33 g (91%) of 35 as a white solid, which was reduced to 36. Rf 0.51 (10% EtOAc/hexane); mp 72–74 °C. IR (CHCl3) 2906, 1713, 1640 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.35 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.72 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.04 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.17 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 4.27 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 5.17 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 6.46 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H, HC=CHCO), 7.00 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.29 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.35–7.42 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.43 (d J = 6.9 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.50 (s, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.52 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.62 (s, 1H, 2-ArH), 7.64 ppm (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO).

4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl]-3-chlorobenzaldehyde (41)

40 (289 mg, 1.00 mmol) yielded after chromatography (10% EtOAc/hexane) 215 mg (78%) of 41 as a white solid, mp 115–116 °C. IR 2902, 1699, 1596, 1262 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.75 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.06 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.19 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 5.19 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.04 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.31–7.56 (m, 8H, 6-ArH, 2′-ArH, 6′-ArH, ArH), 7.81 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.99 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH), 10.01 ppm (s, 1H, CHO). HRMS calcd C30H29ClO2 [M + Na]+ 479.1748, found 479.1763.

3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxy-2-chloro-4-nitrobiphenyl (51)

50 (721 mg, 2.36 mmol) yielded after chromatography (7% EtOAc/hexane) 908 mg (81%) of 51 as a yellow solid, mp 52–54 °C, which was reduced to 52. 1H NMR δ 1.77 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.09 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.21 (m, 6H, AdCH2), 5.21 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.06 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.32 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.35–7.56 (m, 7H, 2′-ArH, 6-ArH, ArH), 8.16 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.4 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 8.37 ppm (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, 3-ArH).

(E)-5-{2-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-2-chloro-4′-hydroxy-4-biphenyl]ethenyl}-1H-tetrazole (24)

A reported procedure73 was applied. To 23 (78 mg, 0.2 mmol) in toluene (2 mL) were added (n-Bu)2SnO (5.0 mg, 0.02 mmol) and azidotrimethylsilane (58 mg, 1.0 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 90–95 °C for 48 h. Additional azidotrimethylsilane (34 mg, 0.3 mmol) was added, and stirring was continued for 20 h. The mixture was concentrated, diluted with EtOAc (10 mL) and 10% HCl (3 mL), and stirred for 0.5 h. The organic layer was washed (water and brine) and dried. Concentration and crystallization (EtOAc/CH2Cl2/hexane) gave 55 mg (64%) of 24 as a white powder, Rf 0.28 (50% EtOAc/hexane); mp 260– 262 °C. IR (CHCl3) 3405, 2966, 2237 cm−1; 1H NMR (C2H3O2H) δ 1.72 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.01 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.12 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 7.09 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H, CH=CH), 7.11 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.22 (s, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.28 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.32 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.40 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.56 (s, 1H, 3-ArH), 7.61 ppm (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H, CH=CH). FTMS (HRMS) calcd C25H25ClN4O (M + H)+ expected 433.1790, found 433.1801.

4-Benzyloxy-3-chlorobenzonitrile (26)

To a solution of 18 (1.23 g, 5 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) and pyridine (2 mL) was added NH2OH·HCl (695 mg, 10 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 50 °C under argon for 5 h and then poured into ice water to give a solid, which was collected by filtration, washed with water, and dried. Chromatography (9% EtOAc/hexane) gave 1.21 g (94%) of oxime 25 as a white solid, which was used for the elimination step.

To 25 (1.1 g, 4.2 mmol) in toluene (15 mL) and pyridine (2 mL) cooled in an ice bath was slowly added methanesulfonyl chloride (798 mg, 7 mmol) over a 10-min period. The mixture was stirred at reflux for 3 h, cooled to room temperature, and diluted with toluene (30 mL). The organic phase was washed (1 N HCl, 5% NaHCO3, water, and brine) and dried. Concentration and chromatography (10% EtOAc/hexane) gave 910 mg (91%) of 26 as a white solid, Rf 0.60 (20% EtOAc/hexane); mp 120–122 °C. IR (CHCl3) 2966, 2232 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 5.23 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.0 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.35–7.45 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.50 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.68 ppm (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH). The crude product was used directly in the next step.

5-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-2-chloro-4′-hydroxy-4-biphenyl]-1H-tetrazole (31)

A reported procedure was applied.73 To 30 (73 mg, 0.2 mmol) in toluene (2 mL) was added (n-Bu)2SnO (5.0 mg, 0.02 mmol) and azidotrimethylsilane (115 mg, 1.0 mmol). This mixture was stirred at 90–95 °C for 48 h and then concentrated. EtOAc (10 mL) and 10% HCl (3 mL) were added. The mixture was stirred for 0.5 h, washed (water and brine), and dried. Concentration and crystallization (EtOAc/CH2Cl2/hexane) produced 58 mg (72%) of 31 as a white powder, Rf 0.27 (50% EtOAc/hexane); mp 235– 240 °C. IR (powder) 3377, 2906, 1486, 1256 cm−1; 1H NMR (C2H3O2H) δ 1.85 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.08 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.22 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 6.83 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.18 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.29 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.57 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 8.01 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 8.18 ppm (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH). FTMS (HRMS) calcd C23H23ClN4O [M + H]+ expected 407.1633, found 407.1630.

Ethyl (E)-4-Benzyloxy-3-chlorocinnamate (32).8,72

To triethyl phosphonoacetate (2.24 g, 10 mmol) in Et2O (20 mL) stirred under argon in a dry ice-acetone bath was added 0.91 M KN(SiMe3)2 (10.0 mmol) in THF (11.0 mL). The mixture was stirred for 0.5 h before 4-benzyloxy-3-chlorobenzaldehyde (18) (2.00 g, 8.1 mmol) in THF (40 mL) was added dropwise over a 0.5-h period, stirred for 1 h more, allowed to warm to room temperature, stirred overnight, poured into water (50 mL) containing HOAc (2 mL), and extracted (Et2O, 100 mL). The extract was washed (water and brine), dried, and concentrated. Chromatography (EtOAC/hexane) afforded 2.3 g (91%) of 32 as a white solid, Rf 0.41 (10% EtOAc/hexane); mp 72–74 °C. IR (CHCl3) 2961, 1706, 1634, 1508 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.33 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 4.25 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 5.20 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 6.31 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO), 6.95 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.36–7.45 (m, 6H, 6-ArH, ArH), 7.56 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO), 7.59 ppm (s, 1H, 2-ArH). This product was debenzylated to 33.

(E)-4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamyl Alcohol (36)

To a stirred solution of 35 (264 mg, 0.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) at −78 °C under argon was added 1.5 mL of 1.0 M DIBAL (1.5 mmol) in hexane. The mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 3 h, diluted with 1 N HCl, and then extracted (EtOAc). The extract was washed (water and brine), dried, and concentrated. Chromatography (10% EtOAc/hexane) gave 220 mg (91%) of 36 as a white powder, Rf 0.28 (20% EtOAc/hexane); mp 72–74 °C. IR (CHCl3) 3399, 2906, 1601 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.73 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.04 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.17 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 4.35 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 5.16 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.64 (td, J = 5.4, 16.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCH2OH), 6.61 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCH2-OH), 7.00 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.30–7.42 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.40 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.42 (s, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.50 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, 5,6-ArH), 7.53 ppm (s, 1H, 2-ArH). HRMS calcd C32H33ClO2 [M + Na]+ 507.2061, found 507.2066.

(E)-4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamaldehyde (37)

To a stirred solution of oxalyl chloride (127 mg, 1 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) at −78 °C under argon was slowly added Me2SO (156 mg, 2 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) according to the method of Swern.48 The solution was stirred at −78 °C for 10 min, 36 (170 mg, 0.35 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was slowly added, and stirring was continued at −78 °C for 20 min before Et3N (303 mg, 3.0 mmol) was added. The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL). The organic layer was washed (water and brine), dried, and concentrated. Chromatography (5% EtOAc/hexane) gave 122 mg (72%) of 37 as a white powder, mp 56–58 °C. IR (CHCl3) 2906, 1681, 1602 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.73 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.05 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.17 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 5.17 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 6.73 (dd, J = 15.2, 7.5 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCHO), 7.02 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.29 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.35–7.44 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.41 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.49 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.50 (s, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.51 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCHO), 7.66 (s, 1H, 2-ArH), 9.73 ppm (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, CHO). FTMS (HRMS) calcd C32H32ClO2 [M + H]+ expected 501.2200, found 501.2276.

General Procedure for Converting Aldehydes 37 and 41 to 2,4-Thiazolidinediones

To a stirred solution of aldehyde (0.1 mmol) and 2,4-thiazolidinedione (23 mg, 0.2 mmol) in toluene (1 mL) were added NHEt2 (0.1 mL) and HOAc (0.05 mL). The mixture was stirred at reflux for 2 h, cooled, and diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 mL). The organic layer was washed (water and brine) and dried. Concentration and chromatography gave the thiazolidinedione.

5-{3-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxy-2-chloro-4-biphenyl]-(2E)-2-propenylidene}-2,4-thiazolidinedione (38)

37 (46 mg, 0.1 mmol) gave 34 mg (62%) of 38 as a yellow powder, Rf 0.31 (30% EtOAc/hexane); mp 212–215 °C. IR (CHCl3) 3186, 1733, 1692 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.73 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.04 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.17 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 5.17 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 6.70 (dd, J = 15.6, 8.7 Hz, 1H, ArCH=CHCH=C), 7.00 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.02 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 1H, ArCH=CHCH=C), 7.27–7.46 (m, 7H, 5-ArH, 6′-ArH, Ar), 7.51 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.52 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.54 (d, J = 15.1 Hz, 1H, ArCH=CHCH=C), 7.60 (s, 1H, 3-ArH), 8.39 ppm (s, 1H, NH). HRMS calcd C35H32ClNO3S [M − H]− 580.1719, found 580.1714.

5-{4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl]-3-chlorobenzylidene}-2,4-thiazolidinedione (42)

41 (46 mg, 0.1 mmol) gave 34 mg (62%) of 42 as a yellow powder, Rf (10% EtOAc/hexane); mp 200–203 °C. IR (CHCl3) 3173, 2904, 1739, 1689 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.74 (s, 6H, AdCH2), 2.05 (s, 3H, AdCH), 2.18 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 6H, AdCH2), 5.18 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.02 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.30 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.35–7.43 (m, 6H, 2′-ArH, ArH), 7.48 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.52 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.60 (d, J = Hz, 1H, 2-ArH), 7.81 (s, 1H, ArCH=C), 8.14 ppm (bs, 1H, NH). HRMS calcd C33H30ClNO3S [M − H]− 554.1562, found 554.1552.

2-{[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxy-2-chloro-4-biphenyl]-methylene}propanedinitrile (44)

A reported procedure49 was adapted. A mixture of 41 (102 mg, 0.22 mmol) and malononitrile (18 mg, 0.27 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (0.6 mL) was stirred in a 103 °C oil-bath for 7 h, cooled to room temperature, and diluted with H2O (8 mL) and EtOAc (80 mL). The organic layer was washed (brine) and dried. The residue obtained on concentration was purified by chromatography (9% EtOAc/hexane) to give 78 mg (70%) of 44 as a yellow solid, mp 170–171 °C, which was deprotected to give 45. 1H NMR δ 1.76 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.08 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.20 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 5.20 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.05 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.32–7.57 (m, 8H, 5-ArH, 2′-ArH, 6′-ArH, ArH), 7.74 (s, 1H, CH=C(CN)2), 7.92–7.96 ppm (m, 2H, 3-ArH, 6-ArH).

(E)-4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamic Acid (46).5

A mixture of 355 (174 mg, 0.34 mmol) and LiOH·H2O (47 mg, 3.3 mmol) in CH3OH/THF/H2O (0.6:1.6:0.55) was stirred for 6 h. After removal of solvent, the residue suspended in H2O (7 mL) and 2 N HCl (5 mL) was extracted with EtOAc (100 mL). The organic layer was washed (brine) and dried. Removal of solvent gave 157 mg (93%) of 46 as a pale-tan solid, which was used directly in the next step. 1H NMR δ 1.74 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.05 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.19 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 5.18 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 6.48 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO), 7.01 (m, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.28–7.55 (m, 9H, 6′-ArH, 2-ArH, 5-ArH, 6-ArH, ArH), 7.66 (s, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.75 ppm (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO).

N-(Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy) (E)-4-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamamide (47)

A reported procedure50 was followed. To a stirred solution of 46 (102 mg, 0.205 mmol) in CHCl3 (4 mL) at 0 °C (ice-bath) were added DMAP (47 mg, 0.39 mmol) and O-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)hydroxylamine (36 mg, 0.31 mmol). Stirring was continued at 0 °C for 20 min more, before DIC (48 µL, 0.31 mmol) was added. After 1 h, the mixture was warmed to room temperature, stirred for 48 h, quenched with saturated NH4Cl (8 mL), and extracted with EtOAc (90 mL). The extract was washed (sat. NH4Cl and brine) and dried. Solvent was removed at reduced pressure and the residue chromatographed (33% EtOAc/hexane) to give 56 mg (46%) of 47 as a pale-tan solid, 91–93 °C. 1H NMR δ 1.64 (m, 4H, 4-THPH, 5-THPH), 1.74 (bs, 6H AdCH2), 1.87 (m, 2H, 3-THPH), 2.06 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.18 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 3.64 (m, 1H, 6-THPH), 3.98 (m, 1H, 6-THPH), 5.06 (bs, 1H, 2-THPH), 5.18 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.01 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.29 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.33–7.46 (m, 7H, CH=CHCO, 5-ArH, ArH), 7.51–7.63 (m, 3H, 2-ArH, 6-ArH, 2′-ArH), 7.72 ppm (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H, CH=CHCO).

3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxyphenyl)-3-chloroaniline (52)

A mixture of 51 (2.08 g, 4.4 mmol) and SnCl2·2H2O (4.96 g, 44 mmol) in EtOH (20 mL) was heated at 88 °C (oil-bath) for 2.5 h, cooled to room temperature, diluted with H2O (10 mL), and adjusted to pH 7–8 by addition of 2 N NaOH (21 mL) and 5% NaHCO3 (19 mL). This mixture was stirred for 1 h and extracted (3 × 350 mL EtOAc). The organic layer was washed (sat. brine) and dried. The concentrated residue was chromatographed (28% EtOAc/hexane) to give 1.766 g (90%) of 52 as a white solid, mp 154–155 °C. IR 3391, 2905, 1189 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.73 (m, 6H, AdCH2), 2.05 (m, 3H, AdCH), 2.18 (m, 6H, AdCH2), 3.73 (bs, 2H, NH2), 5.16 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 6.62 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.4 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 6.8 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, 2-ArH), 6.97 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.15 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.32 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.33–7.55 ppm (m, 5H, ArH). HRMS calcd C29H30ClNO [M + H]+ 444.2089, found 444.2096.

3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxy-4-bromo-2-chlorobiphenyl (53)

To CuBr2 (1.19 g, 5.32 mmol) and tert-butyl nitrite (899 µL, 6.81 mmol) in anhydrous MeCN (5 mL) at 0 °C were slowly added under argon 52 (1.89 g, 4.25 mmol) and MeCN (11 mL), and stirring was continued for 30 min. The mixture was warmed to room temperature, stirred for 2 h, at which time no insoluble 52 remained, quenched with 2 N HCl (100 mL), and extracted (3 × 300 mL Et2O). The organic layer was washed (sat. brine) and dried. After concentration, the residue was chromatographed (hexane) to give 973 mg (45%) of 53 as a pale-yellow solid, mp 58–60 °C. IR 2902, 1220 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 1.74 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.05 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.18 (m, 6H, AdCH2), 5.17 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.01 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.23 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.25 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.32 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.33–7.55 (m, 6H, 5-ArH, ArH), 7.64 ppm (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 3-ArH). HRMS calcd C29H28BrClO [M + H]+ 507.1085, found 507.1068.

3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxy-2-chloro-4-(2-trimethylsilylethynyl) biphenyl (54)

A reported procedure52 was adapted. A mixture of 53 (340 mg, 0.67 mmol), trimethylsilylacetylene (186 µL, 1.34 mmol), Pd(PPh3)4 (92 mg, 0.08 mmol), and CuI (5 mg, 0.026 mmol) was heated at 102 °C (oil-bath) under argon for 3.5 h, cooled to room temperature, diluted with EtOAc (90 mL), and filtered through silica gel. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was chromatographed (1% EtOAc/hexane) to give 350 mg (99%) of 54 as a pale-yellow solid, mp 55–57 °C. IR 2902, 2221, 1286 cm−1; 1H NMR δ 0.27 (s, 9H, Si(CH3)3), 1.74 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.05 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.18 (m, 6H, AdCH2), 5.17 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.01 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.27 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.29 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.30–7.46 (m, 6H, 2′-ArH, ArH), 7.53 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 5-ArH), 7.58 ppm (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 3-ArH). HRMS calcd C34H37ClOSi [M + H]+ 525.2375, found 525.2379.

3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxy-2-chloro-4-ethynylbiphenyl (55)

To a solution of 54 (350 mg, 0.67 mmol) in THF (15 mL) was added 0.9 mL of 1.0 M (n-Bu)4NF (0.88 mmol) in THF. The mixture was stirred for 1 h, diluted with H2O (20 mL), and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 200 mL). The extract was washed (sat. brine) and dried. After concentration, the residue was chromatographed (1% EtOAc/hexane) to give 295 mg (96%) of 55 as a white solid, mp 94–96 °C. 1H NMR δ 1.74 (bs, 6H, AdCH2), 2.06 (bs, 3H, AdCH), 2.18 (m, 6H, AdCH2), 3.14 (s, 1H, C≡CH), 5.17 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.01 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5′-ArH), 7.28 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.4 Hz, 1H, 6′-ArH), 7.31 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 6-ArH), 7.35 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, 2′-ArH), 7.32–7.55 (m, 6H, 5ArH, ArH), 7.6 ppm (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 3-ArH). HRMS calcd C31H29ClO [M + H]+ 453.1980, found 453.1978.

(E)-2-[3′-(1-Adamantyl)-4′-benzyloxy-2-chloro-4-biphenyl]ethenyl-1,3,2-benzodioxaborole (56)