Abstract

2’-Deoxy-N4-[2-(4-nitrophenyl) ethoxycarbonyl]-5-azacytidine (NPEOC-DAC), decitabine with a modification of the N4 position of the azacitidine ring can be used to inhibit DNA methyltransferase. This modification protects the azacitidine ring and can be cleaved by carboxylesterase to release decitabine. NPEOC-DAC was 23-fold less potent at low doses (<10 µM) than decitabine at inhibiting DNA methylation, and was also associated with a 3-day delay in its effect. However, at doses ≥ 10 µM NPEOC-DAC was more effective at inhibiting DNA methylation. Theses differences between decitabine and NPEOC-DAC are dependent on the cleavage of the carboxylester bond, and could be potentially exploited pharmacologically.

Keywords: DNA methylation, decitabine, NPEOC-DAC, carboxylesterase, DNA methyltransferase

Introduction

5-methylcytosine comprises approximately 1% of the human genome, and arises from the post-replicative modification of cytosine by a family of methyltransferase enzymes [1]. Humans are known to have three active enzymes, DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1, 3a, and 3b that transfer a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine to the 5 position of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides [2]. DNA methylation along with histones and histone modification control chromatin structure and gene expression. Abnormal DNA methylation patterns are commonly found in almost all cancer, and are associated with aberrant silencing of tumor suppressor genes [3, 4]. In addition, some cancers appear to have phenotypes that drive aberrant DNA methylation, such as the CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (CIMP) [5].

Cytosine analogs are routinely used in the treatment of cancer as chemotherapeutic agents. One of the most important breakthroughs in the study of DNA methylation came with the discovery that 5-aza derivatives of cytosine [6, 7], which have a nitrogen substitution in the 5-position of the ring, can inhibit DNA methylation [8]. 5-azacytidine (azacitidine, Vidaza) is a ribonucleotide analog, and 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (decitabine, Dacogen), is a deoxyribonucleotide analog. These analogs once incorporated into the DNA in place of cytosine, can covalently trap DNA methyltransferase leading to decrease in DNA methylation [9]. These mechanistic inhibitors of DNA methytransferase are currently approved for use in myelodysplastic syndrome [10, 11], and have clinical activity in other malignancies [12]. Two other pyrimidine analogs, 5-fluorocytidine [13] and zebularine [14, 15], are also mechanistic inhibitors of DNA methyltransferase and currently under clinical development. Other non-mechanistic inhibitors of DNA methyltransferase have been described and are also under investigation [16–18].

Biologically it is clear that mechanistic inhibitors of DNA methyltransferase work best at low doses with prolonged exposures. Jones and Taylor showed that muscle differentiation of 10T1/2 cells induced by azacitidine was due to inhibition of DNA methylation and optimal at lower concentrations of the drug [19]. Clearly lower doses of azacitidine or decitabine are more effective at inhibiting DNA methyltransferase in vitro and in vivo [20–22]. At higher doses the drugs are less effective at inhibiting DNA methylation and cause cytotoxicity. Consistent with this biological observation, Issa and colleagues have shown that clinically these drugs are most effective at a dose of 15mg/m2/day for 10 days, which is approximately 1/20 the maximum tolerated dose with 11 of 18 patients with refractory leukemia responding[22]. Corresponding studies on DNA methylation changes in the peripheral blood of these patients showed that this dose, 15mg/m2/day was the optimal biological dose for inhibiting DNA methylation [23].

In addition to low doses, prolonged exposures to these drugs are important for its effectiveness. Nucleoside analogs that require incorporation into DNA are S-phase specific. Therefore azacytosine derivatives are also more effective at inhibiting DNA methyltransferase with prolonged exposure [24]. Unfortunately azacytosine nucleotides are not stable in aqueous solution. The azacytosine ring of both azacitidine and decitabine can undergo hydrolysis to an inactive form [25]. The half-life of azacitidine is 1.5 +/− 2.3 hours [26] and the half-life of decitabine is 15 to 25 minutes in aqueous solution [27]. The need for prolonged administration, ideally continuous infusion, is impractical due to the aqueous instability of the drug. Thus the drugs require frequent administration and immediate use of the drug once reconstituted from the lysophilized powder form. Compounding the aqueous instability is the fact that cytidine deaminase rapidly metabolizes both azacitidine and decitabine after administration. The in vivo plasma half-life of azacitidine and decitabine are only 41 and 7 minutes respectively due to rapid deamination to azauridine by plasma cytidine deaminase [28, 29].

Patients treated with decitabine show clear decreases in global DNA methylation, but DNA methylation levels quickly return to baseline levels well before the next course and usually within days of stopping drug administration [23]. Development of an oral mechanistic inhibitor of DNA methyltransferase that could be given continuously would provide a convenient route of drug administration that could improve the clinical ability to inhibit DNA methyltransferase and clinical efficacy. Zebularine, another pyrimidine analog is more stable than azacytosine pyrimidine analogs, and is potentially orally bioavailable [15]. However, zebularine is not efficiently metabolized to the triphosphate form and therefore is 100 times less potent than decitabine at inhibiting DNA methyltransferase [15].

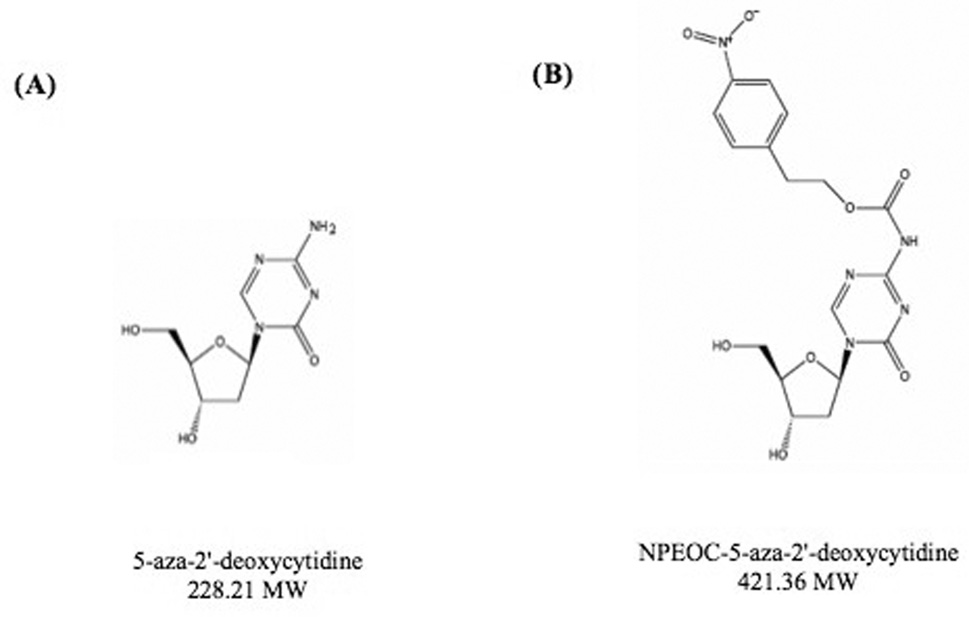

In order to study 5-aza-derivatives of cytosine, azacytosine has been chemically incorporated into an oligonucleotide [30]. In order to protect the azacytosine ring during oligonucleotide synthesis a 2-(p-nitrophenyl) ethoxycarbonyl (NPEOC) protecting group was added to the N4 position of the azacytosine ring creating, N4-NPEOC-DAC (Figure 1). The NPEOC group was then removed chemically using 1, 8-diazabiciclo [5.4.0] undec-7-ene (DBU) after synthesis of the azacitidine containing oligonucleotide. We hypothesized that N4-NPEOC DAC might also inhibit DNA methyltransferase in vivo. Carboxylesterases consist of a family of enzymes that hydrolyze ester and carboxylester bonds. The enzymes have a broad specificity and are involved in the metabolism of xeonobiotics (pesticides, CPT-11, nerve gases, heroin and other drugs), and specific carboxylesterases (CES) subtypes are variably expressed in different human tissues [31]. We speculated that carboxylesterase enzymes could remove the NPEOC protecting group of NPEOC-DAC, and result in the direct release of decitabine in vivo. This is analogous to the prodrug capecitabine (Xeloda) [31], 5’deoxy-5-fluoro-N-[(pentyloxy) carbonyl]-cytidine [32], which is a pyrimidine analog with the addition of a carbon chain on the N4 position via a carboxylester bond. Capecitabine can be converted to 5’-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine by carboxylesterase in the liver and then is further metabolized to 5-fluorouracil the active chemotherapy agent [31]. This drug is currently clinically used as an oral form of 5-fluorouracil in gastrointestinal and breast cancers [33, 34].

Figure 1.

Structure of (A) 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (decitabine, DAC) and (B) N4 2-(p-nitrophenyl) ethoxycarbonyl 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (NPEOC-DAC). The grey oval is NPEOC region

In this study we show that NPEOC-DAC, decitabine with an N4 protecting modification, can be activated to decitabine. Our prodrug can decrease global and gene specific DNA methylation like other azacytosine analogs, but this activity is limited to cells that express carboxylesterase 1. Furthermore, NPEOC-DAC could reactivate ID4 expression, a tumor suppressor gene frequently hypermethylated in cancer.

Material and Methods

Cell lines

T24 cells (urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma), MCF7 (breast adenocarcinoma), Hep G2 cells (hepatocellular carcinoma), Hep 3B2 (hepatocellular carcinoma), were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). T24 were cultured in McCoy's 5A medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Other cells were cultured in DMEM medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells were grown in a humidified 37°C incubator containing 5% CO2.

Nucleic acid isolation

Genomic DNA was isolated by standard proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction [35]. Total RNA was collected and extracted from cultured cells with the RNeasy Protect minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Drug treatments

Synthesis of NPEOC-DAC has been described previously [36]. Cells were seeded at 2 × 104 cells per well in a 12-well dish 24 hours prior to treatments. Cells were treated with decitabine (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO), NPEOC-DAC at the indicated concentrations. Decitabine was dissolved in distilled water and NPEOC-DAC was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Untreated controls of the DMSO solvent alone were also included. Cells were treated at the concentrations indicated for each experiment. Cells were collected the number of days indicated in individual experiments. For subsequent methylation, genomic DNA was extracted using standard phenol/chloroform extraction methods, as described previously [37]. Each experiment was done in triplicate and error bars indicate standard deviations.

Bisulfite treatment

Bisulfite modification of genomic DNA has been described previously [38]. In brief, 1.5 µg of DNA was denatured in 50 µl of 0.2 M NaOH for 10 min at 37°C. Then, 30 µl of freshly prepared 10 mM hydroquinone (Sigma) and 520 µl of 3 M sodium bisulfite (Sigma) at pH 5.0 were added and mixed. The samples were incubated at 50°C for 16 h. The bisulfite-treated DNA was isolated using Wizard DNA Clean-Up System (Promega). The DNA was eluted by 50 µl of warm water and 5.5 µl of 3 M NaOH were added for 5 min. The DNA was ethanol precipitated with glycogen as a carrier and resuspended in 20 µl of water. Bisulfite treated DNA was stored at −20°C until ready for use.

Reverse Transcription and multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

Total RNA (5 µg) extracted from cultured cells was reverse transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and random hexamers (NEB) in a total volume of 20 µl. The reverse transcription was performed according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. To identify expression level of carboxylesterase enzyme, cDNA samples were amplified in a multiplex PCR reaction with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), CES1, and CES2 primers. The gene specific primers were designed to have a similar Tm so that they have similar amplification kinetics by combination with 3 different pair of primers. For ID4 expression, cDNA samples were amplified with ID4 primers. Primer sequences are, GAPDH-F: TGAGGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTC, GAPDH-R:CAGCCGAGCCACATC G, CES1-F: AGAGGAGCTCTTGGAGACGACAT, CES1-R: ACTCCTGCTTGTTAAT TCCGACC, CES2-F: AACCTGTCTGCCTGTGACCAAGT CES2-R: ACATCAGCAG CGTTAACATTTTCTG, ID4-EX-F: CCTGCAGCACGTTATCGACT, ID4-EX-R: CTC AGCGGCACAGAATGC

Pyrosequencing for methylation analysis

Bisulfite-converted DNA was used for pyrosequencing analysis as previously described [39]. In brief, PCR product of each gene was used for individual sequencing reaction. Streptavidin–Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) and Vacuum Prep Tool (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden) was used to purify the single-stranded biotinylated PCR product per the manufacturer’s recommendation. The appropriate sequencing primer was annealed to the purified PCR product and used for a Pyrosequencing reaction using the PSQ 96HS system (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Raw data were analyzed with the allele quantitation algorithm using the provided software. Pyrosequencing was done for LINE-1 elements and ID4 tumor suppressor gene. The PCR primers are, LINE-F: TTTTGAGTTAGGTGTGGGATATA, LINE-R: biotin-AAAATCAAAAAATTCCCTTTC, ID4-F: TTTGATTGGTTGGTTATTTTAGA, ID4-R: biotin-AATATCCTAATCACTCCCTTC. The sequencing primers are, LINE-SP: AGTTAGGTGTGGGATATAGT and ID4-SP: GGTTTTATAAATATAGTTG.

Inhibition of carboxylesterase by nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA)

For dose effects of nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA), a known inhibitor of CES, Hep G2 cells were grown in 6-well plates. Cells were allowed to adhere overnight and were then treated with 100µM of NDGA and 100 µM of NPEOC-DAC or 5µM of decitabine as indicated. Cells were harvested on day 4 by Tripsin-EDTA.

GFP reactivation experiments

NIH 3T3 Cell lines containing an epigenetically silenced GFP transgene in a CMVIE promoter vector (Stratagene, Inc) were used to assay for reactivation of GFP expression. In brief, clone 0Np13 was made by transfecting NIH3T3 cells with a pcnβGFP construct containing a fusion lacZ-GFP gene with a nuclear localization signal under the control of a CMVIE promoter. AflIII-digested DNA was transfected using calcium phosphate and cells were selected with G418. G418R mixed stable clones were pooled and expanded for one week without selection. Both β-galactosidase and GFP expressions were strongly inhibited in NIH3T3. To reactivate GFP, 1×104 cells were plated into one well of a 12-well plate and grown for 1 day in DMEM (Gibo, Life Tchnologies) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum at 37°C in 5% CO2. The medium was changed and transfacted with 1 µg of human CES1 or CES2 transcript expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) using Lipofectamine (Gibo, Life Technologies) according to manufacture’s guide and grown for 1 day. Transfection with CES1 or CES2 was repeated twice additionally with 24 hr time interval. After transfacting three times, treat the cells with fresh medium containing either decitabine or NPEOC-DAC (0.5, 10, 100 µM) and grown 1 day. Next day, GFP expression was determined by florescence microscope.

Statistics

Microsoft Excel was used to perform a standard two-sided t-test to calculate p values.

Results

NPEOC-DAC inhibits DNA methylation in liver cancer cell lines

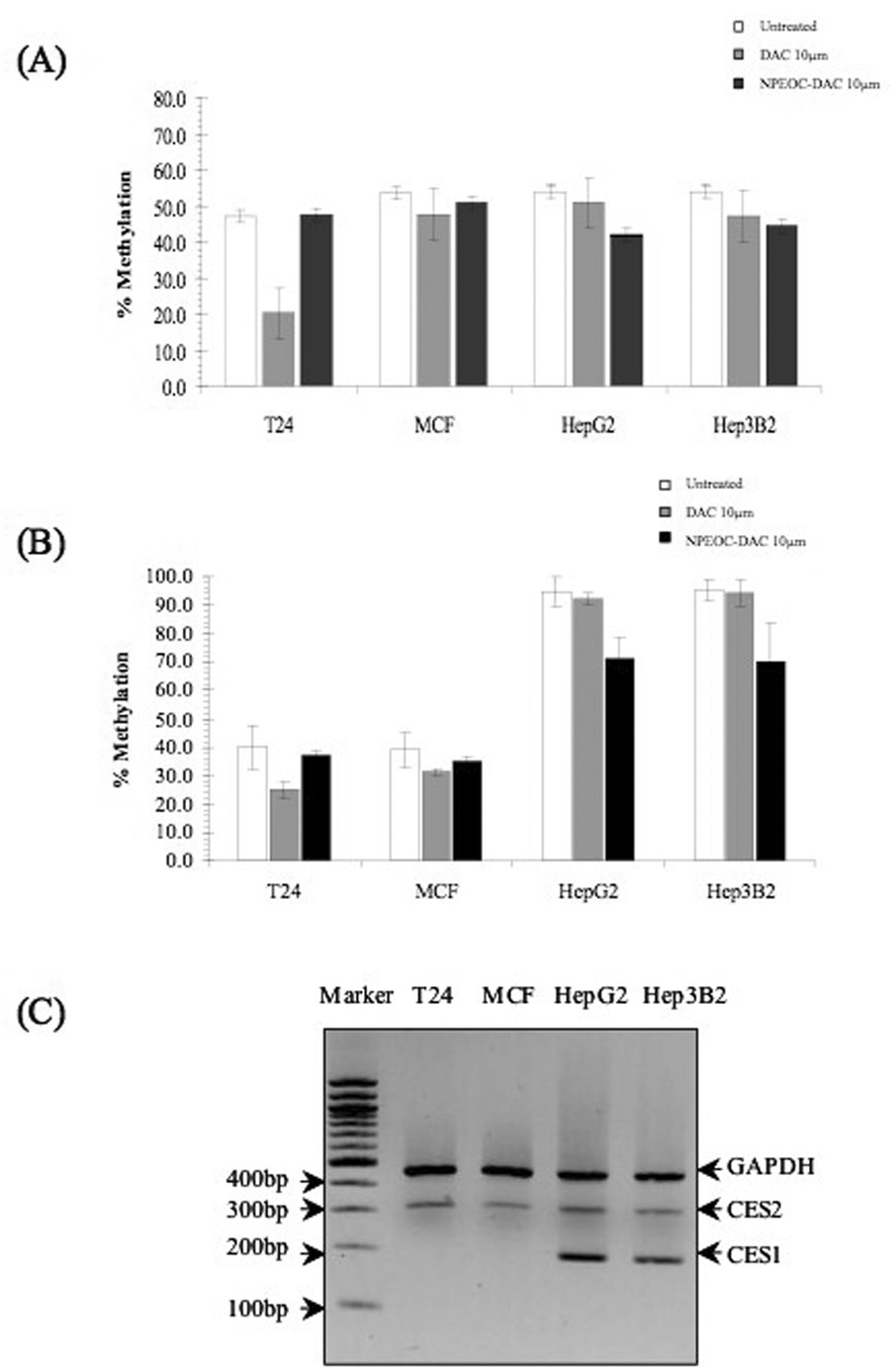

Four cancer cell lines T24 (bladder), MCF7 (breast), Hep G2 (liver), and Hep 3B2 (liver) were treated with decitabine and NPEOC-DAC for three days. Global DNA methylation was quantitated using bisulfite-PCR Pyrosequencing of LINE-1 DNA repetitive elements. PCR primers were designed towards a consensus LINE-1 sequence and a pool of LINE-1 elements was assayed as a surrogate of global DNA methylation. Decitabine decreased global DNA methylation by 57.1%, 11.0%, 5.6% and 12.3% in T24, MCF, Hep G2 and Hep 3B2 cell lines respectively. NPEOC-DAC decreased global DNA methylation by 0.9%, 5.1%, 22.1% and 17.4% in T24, MCF, Hep G2 and Hep 3B2 cell lines respectively (Figure 2A). T24 cell lines were very sensitive to decitabine, and only the liver cell lines showed a significant decrease in DNA methylation when treated with NPEOC-DAC (p=0.01).

Figure 2.

DNA methylation changes induced by DAC (decitabine) and NPEOC-DAC. Various cell lines were treated with either 10µM DAC or 10µM NPEOC-DAC for three days. Global DNA methylation was quantitated using bisulfite-PCR Pyrosequencing of the LINE-1 repetitive element (A) and ID4 (B). All experiments were performed in triplicate and error bars represent standard deviation. (C) Carboxylesterase expression in various cell lines. Reverse Transcriptase Multiplex PCR of carboxylesterase 1 and carboxylesterase 2 was performed on cDNA from the cell lines studied. Expression of the CES1, which is the most abundantly expressed carboxylesterase, was limited to the liver cancer cell lines, Hep3B and Hep G2.

Gene specific DNA methylation changes were also assessed by measuring changes in ID4, Inhibition of DNA-binding 4. Baseline methylation of ID4 was 40.2%, 39.0%, 94.7% and 95.4% in the T24, MCF, Hep G2 and Hep 3B2 cell lines respectively. There was a higher baseline methylation of ID4 in the liver cell lines. DNA methylation of ID4 decreased by 38.1%, 19.7%, 2.6% and 1.1% in T24, MCF, Hep G2 and Hep 3B2 cell lines respectively when treated with decitabine. Conversely, DNA methylation of ID4 decreased by 8.2%, 10.0%, 24.7% and 26.2% in T24, MCF, Hep G2 and Hep 3B2 cell lines respectively when treated with NPEOC-DAC (Figure 2B). Decitabine decreased ID4 methylation very efficiently in T24 cells, but the other cell lines seemed more resistant to decitabine at 10 µM. Again NPEOC-DAC significantly decreased DNA methylation only in Hep G2 and Hep 3B2 cell lines (P=0.0005).

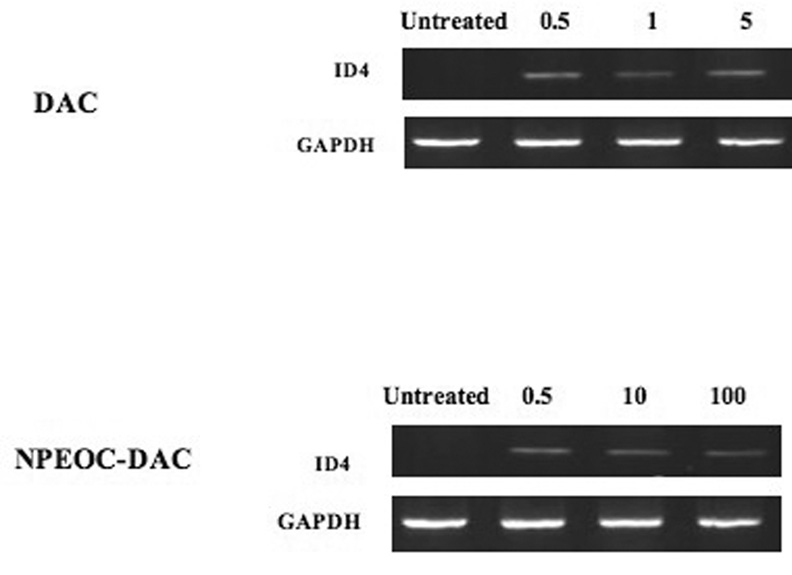

NPEOC-DAC reactivates expression of ID4

Clearly NPEOC-DAC was able to decrease the methylation of ID4, we next examined whether NPEOC-DAC could reactivate expression of this epigenetically silenced gene. Hep G2 cells do not normally express ID4, however when treated with decitabine for 3 days clear expression of ID4 could be detected by reverse transcription PCR (Figure 3). Treatment of Hep G2 cells with NPEOC-DAC also showed recovered expression of ID4. Therefore both decitabine and NPEOC-DAC clearly decreased the methylation of the ID4 promoter, which led to increased ID4 expression level.

Figure 3.

DAC (decitabine) and NPEOC-DAC reactivates expression of ID4 gene. Hep G2 cells were treated with DAC or NPEOC-DAC at the concentrations indicated (µM). Total RNA was isolated after 3 days of treatment and mRNA expression of ID4 was measured by RT-PCR. Untreated Hep G2 cells had no detectable ID4 expression, but treatment by either DAC or NPEOC-DAC lead to expression of ID4.

Carboxylesterase 1 is expressed only in liver cancer cell lines

We hypothesized that the carboxylesterase is responsible for the cleavage of the N4 carboxylester bond needed to convert NPEOC-DAC into decitabine. We wanted to assess carboxylesterase expression in the cell lines studied. CES1 has been previously reported as the most ubiquitously expressed enzyme in humans [40, 41]. We used multiplex RT-PCR assay to determine expression of carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) and 2 (CES2) in the cell lines studied. CES1 was expressed only in the liver cells Hep G2 and Hep 3B2. CES2 was more broadly expressed in all the cell lines, but at lower levels (Figure 2C).

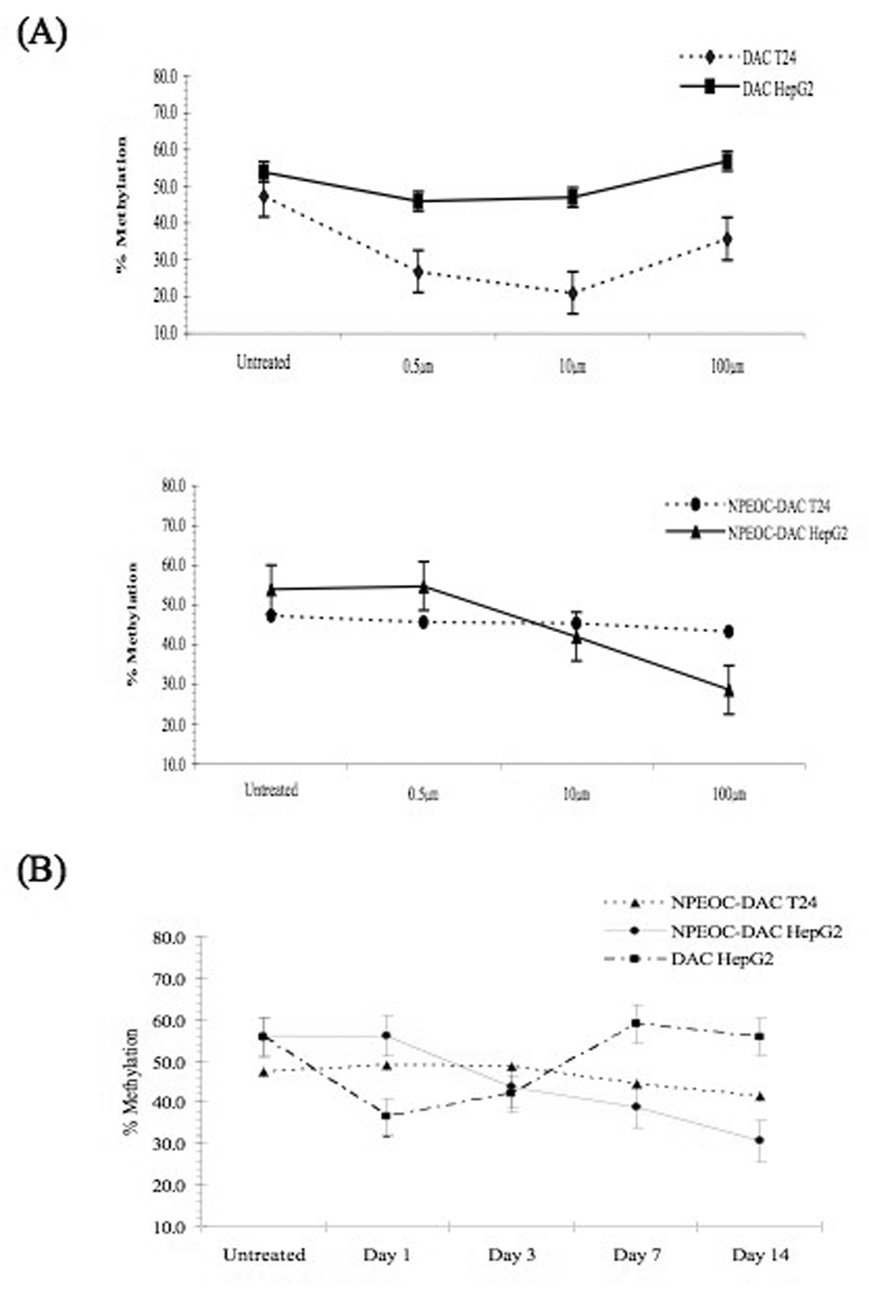

Dose dependent effect of decitabine and NPEOC-DAC

T24 and Hep G2 cells were used for more detailed investigations of the ability of NPEOC-DAC to inhibit DNA methylation. Untreated Hep G2 cells have a baseline LINE-1 methylation of 53.9(±6)%. This decreased slightly treated with 0.5 µM, 1 µM or 5 µM decitabine to 46.0(±2.3)%, 47.0(±1.9)% and 56.9(±1.0)% respectively. This paradoxical increase at higher concentrations is associated with significant cell toxicity (data not shown), which is likely selecting for cells with higher methylation levels. T24 cells showed a lower baseline LINE-1 methylation of 47.3(±3.3)%, but were more sensitive to decitabine. LINE-1 methylation decreased to 26.8(±0.8)%, 21.0(±0.1)% and 35.7(±3.6)% when treated with 0.5 µM, 1 µM and 5 µM decitabine. As previously described there was a parabolic effect on the effect of DNA methylation with lower doses around 1 µM having the maximal effect on DNA methylation.

NPEOC-DAC effectively inhibited DNA methylation in Hep G2 cells, but required higher concentrations. NPEOC-DAC at 0.5 µM had no detectable effect on DNA methylation, but 10 µM NPEOC-DAC decreased methylation to 42.0(±1.1)% and 100 µM NPEOC-DAC was able to decrease LINE-1 methylation to 28.7(±5.0)%. This decrease was greater than the strongest effect observed with decitabine. T24 cells were unaffected by NPEOC-DAC, and there appeared to be no change in DNA methylation even at the highest concentrations of NPEOC-DAC (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) LINE-1 DNA methylation changes at various concentrations of DAC (decitabine) and NPEOC-DAC. The T24, bladder cancer cell line, and Hep G2, liver cancer cell line, were treated for 3 days with various concentrations of either DAC (upper panel) or NPEOC-DAC (middle panel). (B) Time course of DNA methylation changes. T24 and Hep G2 cell lines were treated continually with either DAC (decitabine, 10 µM) or NPEOC-DAC (10 µM) and DNA methylation of LINE-1 was assessed on days 1, 3, 7 and 14.

Time dependent effect of NPEOC-DAC

NPEOC-DAC is a prodrug and needs to be converted to decitabine in order to have activity. In order to investigate this possibility we investigated the time dependence of NPEOC-DAC to inhibit DNA methylation. Decitabine significantly decreased methylation in Hep G2 cells from 53.9(±6.0)% to 36.5(±3.2)% by day 1 of treatment (Figure 4B). However, subsequent days of treatment led to a decrease in this effect, and by day 7 the LINE-1 methylation returned to baseline. Again, this treatment with high concentrations of decitabine, 10 µM, was associated with significant toxicity (data not shown). Thus there may have been a selection phenomenon where the cells with a selective advantage have higher LINE-1 methylation levels. Conversely NPEOC-DAC did not begin to decrease LINE-1 methylation until day 3 of treatment. LINE-1 methylation decreased from 53.9(±6.0)% to 43.7(±4.0)% on day 3, 38.9(±3.8)% on day 7 and finally to 30.9(±3.1)% on day 14. This delayed effect could be attributable to the time required to convert NPEOC-DAC to decitabine. In addition there was less toxicity then observed with decitabine, which is likely due to the slow conversion of NPEOC-DAC to decitabine. T24 cells did not show any decrease in DNA methylation despite prolonged treatment with NPEOC-DAC.

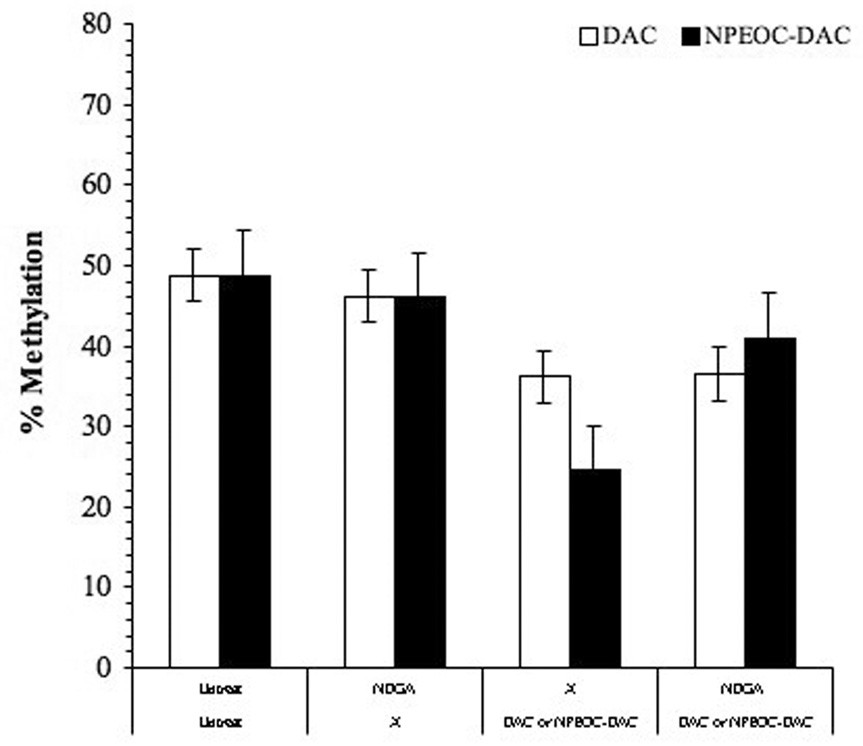

Inhibition of Carboxylesterase inhibits the ability of NPEOC-DAC to induce hypomethylation

Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) is a known inhibitor of carboxylesterase [42]. In order to confirm the ability of NPEOC-DAC to inhibit DNA methylation is dependent on carboxylesterase, we treated cells with a combination of NDGA and NPEOC-DAC. NDGA at 100 µM had no affect on the DNA methylation of Hep G2 cells. Hep G2 cells treated with 10 µM NPEOC-DAC alone decreased LINE-1 methylation from 49.7% to 24.5(±0.6)% (Figure 5). However, NPEOC-DAC in combination with NDGA showed that LINE-1 methylation did not decrease. Thus NDGA inhibited the ability of carboxylesterase enzyme which has activity to convert NPEOC-DAC to decitabine, therefore NPEOC-DAC remained inactivate form without inhibition of DNA methylation.

Figure 5.

NDGA inhibits the ability of NPEOC-DAC to inhibit DNA methylation. Hep G2 cells were treated with either DAC (1 µM) or NPEOC-DAC (100 µM) in the presence or absence of NDGA, which is known inhibitor of carboxylesterase enzyme.

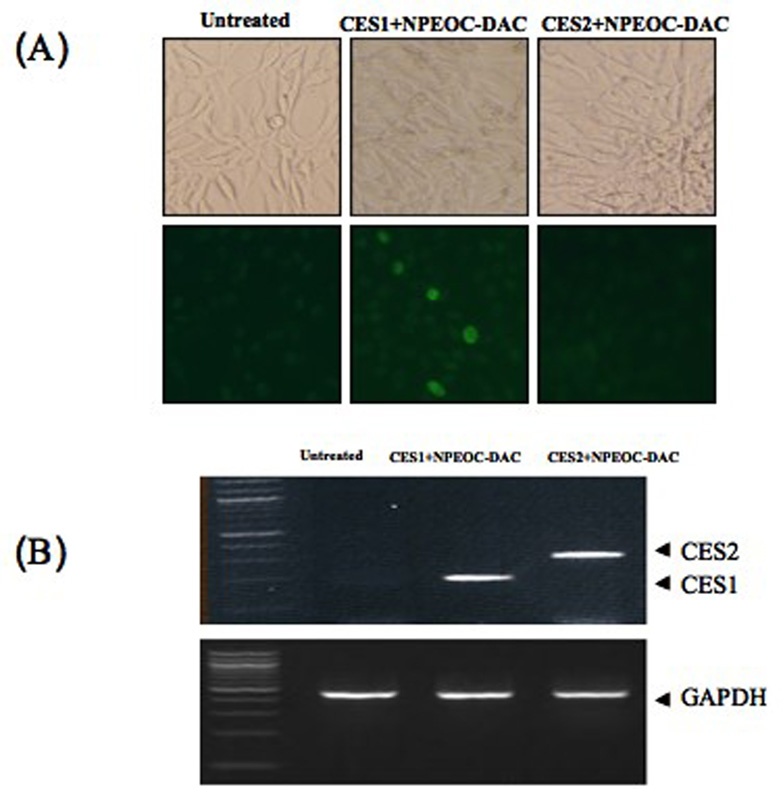

NPEOC-DAC requires CES1 expression in order to reactivate an epigenetic silenced GFP reporter gene

We found that NPEOC-DAC could inhibit DNA methylation in cells expressing CES1 but not cells expressing CES2 (Figure 2C), and that inhibition of CES by NDGA blocked the ability of NPEOC-DAC to inhibit DNA methylation. To further demonstrate the dependence of NPEOC-DAC on CES1 we carried out transient transfection of CES1 or CES2 expression vector along with NPEOC-DAC treatment in an epigenetic GFP reporter system. NIH3T3 cells with a stably transfected GFP reporter gene were cultured until the GFP expression became epigenetically extinguished, and then a clone that could be reactivated by decitabine was selected (data not shown). This cell line was then treated with NPEOC-DAC without reactivation of GFP (data not shown). However, transient transfection of the human CES1 gene and treatment with NPEOC-DAC lead to reactivation of GFP (Figure 6). Transfection of CES1 alone without NPEOC-DAC treatment did not reactivate GFP (data not shown). Transfection of CES2 had no effect on NPEOC-DAC treatment and activation of GFP. Therefore, NPEOC-DAC activation is dependent on CES1 expression.

Figure 6.

CES1 dependent activation of NPEOC-DAC in epigenetically silenced GFP cells. NIH3T3 cells with a GFP gene that is epigenetically silenced were treated with NPEOC-DAC and transiently transfected with human CES1 or CES2. (a) untreated NIH3T3 cells, (b) NPEOC-DAC treated with CES1 transfection, (c) NPEOC-DAC treated with CES2 transfection.

Discussion

We have clearly demonstrated that NPEOC-DAC can inhibit global DNA methylation as demonstrated by induction of hypomethylation of the LINE-1 repetitive element. Furthermore we demonstrate the NPEOC-DAC can reverse hypermethylation of a tumor suppressor gene, ID4, and reactive expression of the gene. This ability to inhibit DNA methylation is specific for the liver cancer cell lines Hep G2 and Hep 3B2, and dependent on the activity of the carboxylesterase 1 enzyme. Thus NPEOC-DAC is a prodrug that can be metabolized to decitabine and incorporate into DNA and lead to irreversible inhibition of the DNA methyltransferase enzyme.

The modification of decitabine at the N4 position was first carried out to stabilize the azacytosine ring during production of a phosphoramidate version of azacitidine that would be chemically stable enough to incorporate into a synthetic oligonucleotide. We show here that one intermediate of the NPEOC protected phosphoramidite of azacitidine, NPEOC-DAC, is able to specifically inhibit DNA methylation after activation of NPEOC-DAC into decitabine is carried out by the cleavage of the N4 nitrophenyl group by human CES1. We have found NPEOC-DAC, unlike decitabine, to have very low solubility in water and was therefore dissolved in DMSO. The increased hydrophobicity of the compound could potentially lead to very favorable human pharmacokinetics including oral bioavailability. One could perceive NPEOC-DAC or some other N4 derivative of decitabine or azacitidine that could be administered orally, survive the acidic environment of the stomach, and then be metabolized to an active pyrimidine by first pass metabolism of the liver.

NPEOC-DAC was less potent at inhibiting DNA methyltrasferase at same concentration. NPEOC-DAC was 23-fold less efficient at inhibiting DNA methylation compared to decitabine. In addition there appeared to be a 3-day delay in the effects of NPEOC-DAC compared to decitabine. We assume that this is due to the delayed effect of converting the prodrug NPEOC-DAC to decitabine. Carboxylesterases have variable expression in different tissues, and may not be 100% efficient in converting NPEOC-DAC to decitabine. Capecitabine, which is activated to 5-FU by a similar mechanism, appears to be much more efficiently converted to its active form [31]. We speculate that the N4 protecting group of capecitabine with a simple 5-carbon chain at the N4 position allows for more efficient cleavage of capecitabine to 5-fluorocytidine. Alternatively NPEOC-DAC is chemically different and may be metabolized differently than decitabine or capecitabine. Thus, changing the N4 NPEOC group of NPEOC-DAC to a smaller carbon chain may lead to a molecule much more efficient at inhibiting DNA methylation.

Carboxylesterase consists of a family of enzymes that have different specificities for different carboxylesterase molecules. The expression pattern of different carboxylesterase genes varies from tissue to tissue, which can be exploited pharmacologically. For example CES3 is specifically expressed in the brain [43], and a carboxylester molecule specific for CES3 could be directed to the brain by CES3 specific prodrug activation. One could theoretically modify the N4 carboxylester bond and side group to target specific members of the carboxylesterase enzyme family and therefore potentially target activation and release of the active drug in specific tissues or organs. Conversely the N4 group could be modified to avoid certain tissues, such as the bone marrow, and therefore avoid unwanted toxicity such as myelosuppression. Thus allowing organ specific targeting therapy using epigenetic prodrug.

There has been much interest in the combination of DNA methylation inhibitors with other epigenetic agents such as histone deacetylase inhibitors. Some of these inhibitors such as valproic acid, phenylbutyrate and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) [44] consist of carbon chains that could be attached to decitabine at the N4 position with a carboxylester bond. Addition of another active agent to the N4 position of decitabine would then lead to a two-sided drug where cleavage of the carboxylester bond could release two active agents. Therefore our prodrug system could not only be used for targeted delivery of a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, but could also be used for delivery of a combination of epigenetic therapies depending on the group added as the N4 modification.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bird A. The essentials of DNA methylation. Cell. 1992;l70(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90526-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu SC. S-Adenosylmethionine. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;l32(4):391–395. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones PA, Buckley JD. The role of DNA methylation in cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1990;l54:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60806-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spruck CH, 3rd, Rideout WM, 3rd, Jones PA. DNA methylation and cancer. Exs. 1993;l64:487–509. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9118-9_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;l4(12):988–993. doi: 10.1038/nrc1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman S. The effect of 5-azacytidine on E. coli DNA methylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;l89(4):1328–1333. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)92154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorm F, Vesely J. The Activity of a New Antimetabolite, 5-Azacytidine, against Lymphoid Leukaemia in Ak Mice. Neoplasma. 1964;l11:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones PA, Taylor SM. Cellular differentiation, cytidine analogs and DNA methylation. Cell. 1980;l20(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheikhnejad G, Brank A, Christman JK, Goddard A, et al. Mechanism of inhibition of DNA (cytosine C5)-methyltransferases by oligodeoxyribonucleotides containing 5,6-dihydro-5-azacytosine. J Mol Biol. 1999;l285(5):2021–2034. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverman LR, Demakos EP, Peterson BL, Kornblith AB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome: a study of the cancer and leukemia group B. J Clin Oncol. 2002;l20(10):2429–2440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantarjian H, Issa JP, Rosenfeld CS, Bennett JM, et al. Decitabine improves patient outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes: results of a phase III randomized study. Cancer. 2006;l106(8):1794–1803. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert J, Gore SD, Herman JG, Carducci MA. The clinical application of targeting cancer through histone acetylation and hypomethylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;l10(14):4589–4596. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Randerath K, Tseng WC, Harris JS, Lu LJ. Specific effects of 5-fluoropyrimidines and 5-azapyrimidines on modification of the 5 position of pyrimidines, in particular the synthesis of 5-methyluracil and 5-methylcytosine in nucleic acids. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1983;l84:283–297. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-81947-6_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marquez VE, Kelley JA, Agbaria R, Ben-Kasus T, et al. Zebularine: a unique molecule for an epigenetically based strategy in cancer chemotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;l1058:246–254. doi: 10.1196/annals.1359.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng JC, Matsen CB, Gonzales FA, Ye W, et al. Inhibition of DNA methylation and reactivation of silenced genes by zebularine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;l95(5):399–409. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi ST, Wang ZY, Smith TJ, Hong JY, et al. Effects of green tea and black tea on 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone bioactivation, DNA methylation, and lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice. Cancer Res. 1994;l54(17):4641–4647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villar-Garea A, Fraga MF, Espada J, Esteller M. Procaine is a DNA-demethylating agent with growth-inhibitory effects in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;l63(16):4984–4989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brueckner B, Boy RG, Siedlecki P, Musch T, et al. Epigenetic reactivation of tumor suppressor genes by a novel small-molecule inhibitor of human DNA methyltransferases. Cancer Res. 2005;l65(14):6305–6311. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor SM, Jones PA. Multiple new phenotypes induced in 10T1/2 and 3T3 cells treated with 5-azacytidine. Cell. 1979;l17(4):771–779. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Issa JP. Optimizing therapy with methylation inhibitors in myelodysplastic syndromes: dose, duration, and patient selection. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;l2 Suppl 1:S24–S29. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant S, Bhalla K, Gleyzer M. Interaction of deoxycytidine and deoxycytidine analogs in normal and leukemic human myeloid progenitor cells. Leuk Res. 1986;l10(9):1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(86)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Issa JP, Garcia-Manero G, Giles FJ, Mannari R, et al. Phase 1 study of low-dose prolonged exposure schedules of the hypomethylating agent 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (decitabine) in hematopoietic malignancies. Blood. 2004;l103(5):1635–1640. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang AS, Doshi KD, Choi SW, Mason JB, et al. DNA methylation changes after 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine therapy in patients with leukemia. Cancer Res. 2006;l66(10):5495–5503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidson S, Crowther P, Radley J, Woodcock D. Cytotoxicity of 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine in a mammalian cell system. Eur J Cancer. 1992;l28(2–3):362–368. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Notari RE, DeYoung JL. Kinetics and mechanisms of degradation of the antileukemic agent 5-azacytidine in aqueous solutions. J Pharm Sci. 1975;l64(7):1148–1157. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600640704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudek MA, Zhao M, He P, Hartke C, et al. Pharmacokinetics of 5-azacitidine administered with phenylbutyrate in patients with refractory solid tumors or hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;l23(17):3906–3911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Momparler RL. Pharmacology of 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine (decitabine) Semin Hematol. 2005;l42 3 Suppl 2:S9–S16. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaminskas E, Farrell A, Abraham S, Baird A, et al. Approval summary: azacitidine for treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;l11(10):3604–3608. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Groeningen CJ, Leyva A, O'Brien AM, Gall HE, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (NSC 127716) in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1986;l46(9):4831–4836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabbara S, Bhagwat AS. The mechanism of inhibition of DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferases by 5-azacytosine is likely to involve methyl transfer to the inhibitor. Biochem J. 1995;l307(Pt 1):87–92. doi: 10.1042/bj3070087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miwa M, Ura M, Nishida M, Sawada N, et al. Design of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine, which generates 5-fluorouracil selectively in tumours by enzymes concentrated in human liver and cancer tissue. Eur J Cancer. 1998;l34(8):1274–1281. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verweij J. Rational design of new tumoractivated cytotoxic agents. Oncology. 1999;l57 Suppl 1:9–15. doi: 10.1159/000055263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moertel CG, Rubin J, O'Connell MJ, Schutt AJ, et al. A phase II study of combined 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in the treatment of advanced upper gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 1986;l4(7):1053–1057. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.7.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tominaga T, Nomura Y, Uchino J, Hirata K, et al. Cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, 5-fluorouracil and high-dose toremifene for patients with advanced/recurrent breast cancer. The Japan Toremifene Cooperative Study Group. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;l28(4):250–254. doi: 10.1093/jjco/28.4.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolff RK, Frazer KA, Jackler RK, Lanser MJ, et al. Analysis of chromosome 22 deletions in neurofibromatosis type 2-related tumors. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;l51(3):478–485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guimil Garcia R, Brank AS, Christman JK, Marquez VE, et al. Synthesis of oligonucleotide inhibitors of DNA (Cytosine-C5) methyltransferase containing 5-azacytosine residues at specific sites. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2001;l11(6):369–378. doi: 10.1089/108729001753411335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Zulueta M, Bender CM, Yang AS, Nguyen T, et al. Methylation of the 5' CpG island of the p16/CDKN2 tumor suppressor gene in normal and transformed human tissues correlates with gene silencing. Cancer Res. 1995;l55(20):4531–4535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark SJ, Harrison J, Paul CL, Frommer M. High sensitivity mapping of methylated cytosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;l22(15):2990–2997. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang AS, Estecio MR, Doshi K, Kondo Y, et al. A simple method for estimating global DNA methylation using bisulfite PCR of repetitive DNA elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;l32(3):e38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satoh T, Taylor P, Bosron WF, Sanghani SP, et al. Current progress on esterases: from molecular structure to function. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;l30(5):488–493. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.5.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Munger JS, Shi GP, Mark EA, Chin DT, et al. A serine esterase released by human alveolar macrophages is closely related to liver microsomal carboxylesterases. J Biol Chem. 1991;l266(28):18832–18838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schegg KM, Welch W., Jr The effect of nordihydroguaiaretic acid and related lignans on formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase and carboxylesterase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;l788(2):167–180. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(84)90259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mori M, Hosokawa M, Ogasawara Y, Tsukada E, et al. cDNA cloning, characterization and stable expression of novel human brain carboxylesterase. FEBS Lett. 1999;l458(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marks PA, Richon VM, Kelly WK, Chiao JH, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: development as cancer therapy. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;l259:269–281. discussion 281–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]