Abstract

The intramolecular cyclohexadienone annulation of chromium carbene complexes is examined as a method to provide general access to the Phomactin family of natural products. The importance of the stereochemistry of the carbene complex and the number of carbons in the tether connecting the carbene complex and the alkyne are probed. Additionally, the degree of the 1,4-asymmetric induction is examined.

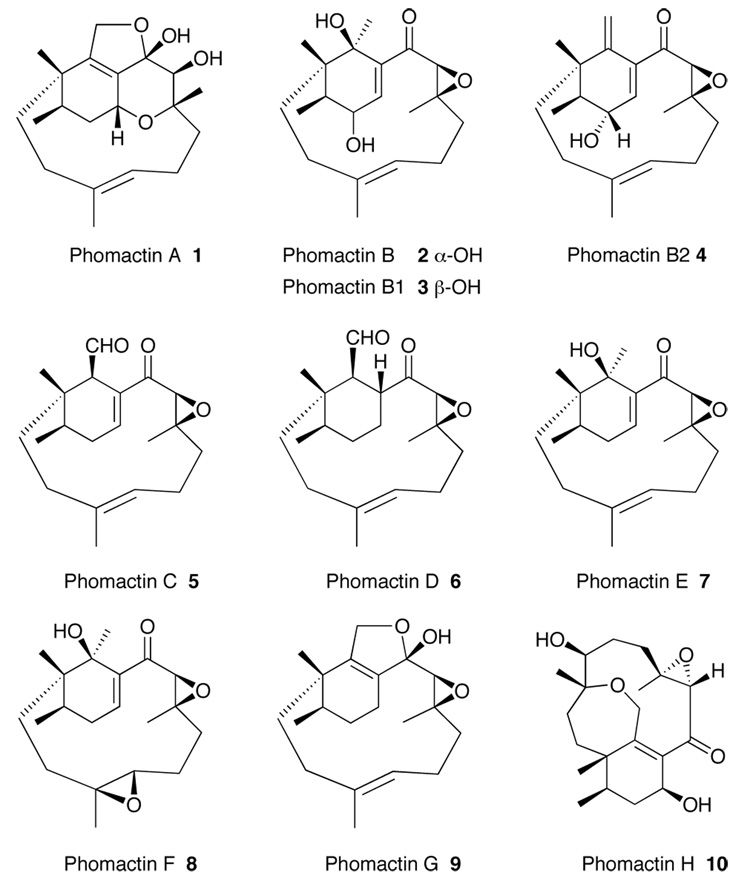

Since the discovery1 of the phomactins in the early to mid 1990’s, their unusual carbon skeleton combined with attractive bioactivity as PAF antagonists has prompted much interest among synthetic organic chemists.2,3,4 The structures of the phomactins share a common bicyclo [9.3.1] pentadecane ring system featuring a highly substituted cyclohexane bearing a quarternary center and a 12-membered macrocycle (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Phomactin Family of Natural Products.

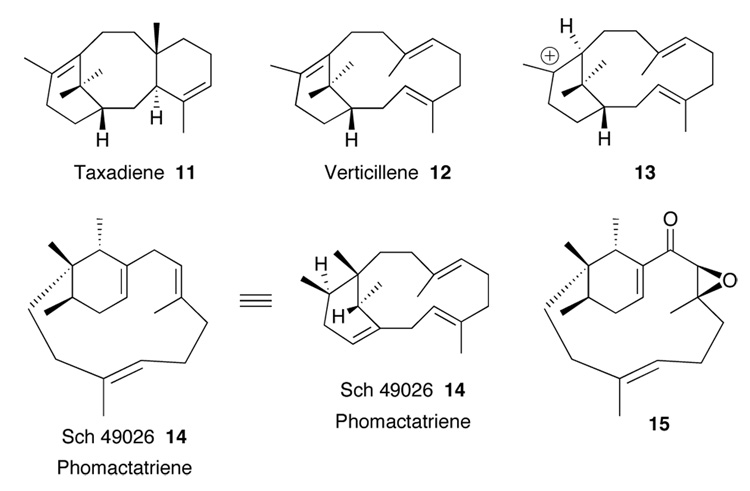

The phomactins and members of the taxol family share a common biosynthetic pathway (Figure 2).2,5 Cyclization of geranylgeranyl diphosphate gives rise to the verticillenyl carbocation 13 which can lead to verticilllene 12 by simple proton loss or to taxadiene 11 via an intramolecular proton transfer and subsequent intramolecular cyclization. Alternatively, it has been shown that cation 13 is the precursor to phomactatriene 14 via a series of 1,2-hydrogen and 1,2-methyl shifts.5a Phomactatriene 14 is also a natural product and has been isolated from Phoma sp. and its stereochemistry recently corrected.5b It has been suggested by Pattenden that the last common intermediate to all the phomactins in the biosynthesis is the keto expoxide 15 which results from oxidations of phomactatriene.2

Figure 2.

Biosynthesis of Phomactins and Taxol.

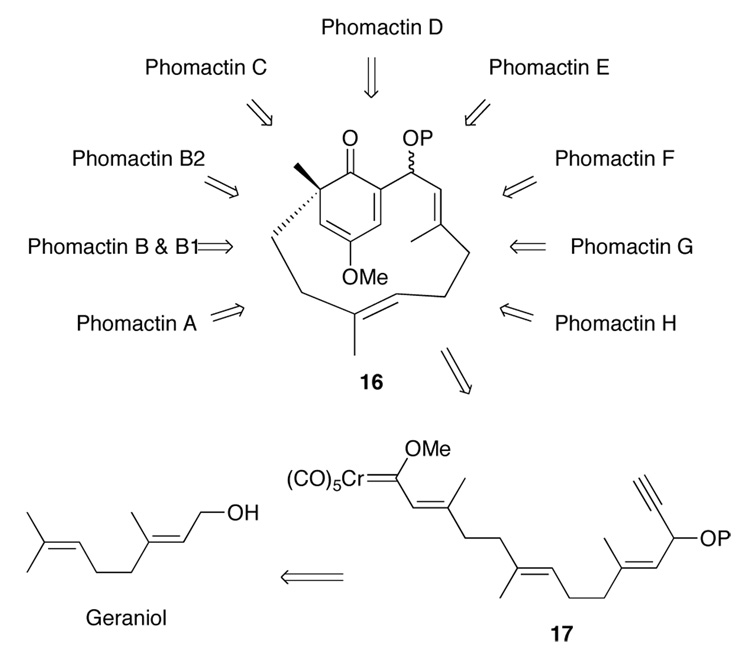

We envisioned that the bicyclic cyclohexadienone 16 could also serve as a common intermediate for the synthesis of all of the phomactins in much the same way that the epoxy ketone 15 has been proposed to be the biosynthetic precursor to all of the phomactins.2 All of the previous synthetic approaches3 and total syntheses4 of the phomactins have constructed the six-membered ring before the macrocycle is closed. Closure of the macrocycle has been effected by a number of different tactical methods including NHK coupling,4b,4d–e,3i Suzuki coupling,4c,3e Stille coupling,3k sulfone coupling to an allyic halide,4a,3n and oxa[3+3] cycloaddition.3m,3q Our retrosynthesis for the phomactins involves the intramolecular cyclohexadienone annulation of the carbene complex 17 (Scheme 1). Thermolysis of 17 would be anticipated to lead to the formation of 6 membered and 12 membered ring in the same event.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis for the Phomactins

The benzannulation reaction of α,β-unsaturated carbene complexes with alkynes is one of the most important methods for the synthesis of phenols (Scheme 2). This reaction was discovered in 1975 by Dötz and since that time6 the reaction has been extensively studied and widely applied in organic synthesis.7 We reported the cyclohexadienone annulation in 1985 which involves the reaction of carbene complexes of the type 18 where both substituents of the β-carbon are non-hydrogen.8 The reaction of such complexes with alkynes is general and allows for rapid entry to cyclohexadienones bearing a quaternary carbon.7 The intramolecular variant of the benzannulation reaction has been known9,10 for quite some time and has been utilized in the total synthesis of deoxyfrenolicin,9b,c,g angelicin,9d,e sphondin,9e and arnebinol.9h The intramolecular version of the cyclohexadienone annulation is unknown and is the subject of the present work.

Scheme 2.

Cyclohexadienone Annulation and Benzannulation

The retrosynthesis of the phomactins shown in Scheme 1 requires the carbene complex 17 and thus as model systems we chose to prepare a family of carbene complexes of the type 22 (Scheme 2) in which the alkyne is tethered to the β-carbon of the alkenyl substituent of the carbene complex. It was anticipated that it would be important not only to include complexes of the type 22 with different tether lengths in the initial screen of the intramolecular cyclohexadienone annulation but also to include complexes with both cis and trans double-bonds in the carbene complex. It is known11 that β,β-disubstituted alkenyl carbene complexes are configurationally stable under the conditions of the cyclohexadienone annulation and thus it is certainly possible that cis and trans isomers of 22 could behave differently during the intramolecular process involving the carbene complex and the tethered alkyne unit. The E-isomer of complex 22 was prepared from the E-vinyl iodide precursor E-21 via the standard Fischer method involving the addition of the vinyllithium derived from E-21 with chromium hexacarbonyl followed by methylation. The Z-isomer of 22 was prepared from the corresponding Z-isomer of the vinyl iodide 21 (not shown) and the details can be found in the supporting information. More rapid entry to these carbene complexes is possible via the aldol reaction12 of the methyl carbene complex 23 with the ketone 24 (Scheme 2), unfortunately, this route produces a mixture of the Z- and E-isomers of 22 which proved to be inseparable.

The intramolecular cyclohexadienone annulation of carbene complex 22 was examined with complexes of four different tether lengths and the results are presented in Table 1. The yield of the desired bicyclic cyclohexadienone 25 increases with increasing tether length until n = 10 and then appears to level off. The phomactins have nine carbons in the larger bridge and the results in Table 1 are encouraging since reasonable yields of the cyclized product 25 can be realized with both eight and ten methylene tethers. However, none of the desired cyclized product 25 is seen with the complex 22a with six methylene spacers. In this case, depending on solvent, up to a 46% yield of the dimeric cyclohexadienone 26 was observed as a 1.1:1.0 mixture of diastereomers along with smaller amounts of the corresponding trimeric product (not shown). In acetonitrile the ratio of the dimers was formed in a 1.8:1.0 ratio and the stereochemistry of the major diastereomer was confirmed by an X-ray diffraction study. This study of intramolecular cyclohexadienone annulation of complexes 22 also clearly reveals that the stereochemistry of the double-bond of the carbene complex is very important. The Z-isomer of complex 22 gives a 15% yield of 25, whereas, the E-isomer gives a 43% yield (entries 7 vs. 9). Interestingly, a 79:21 mixture of E:Z isomers of 22c was prepared by the aldol reaction indicated in Scheme 2 and the thermolysis of this mixture gave a 37% yield of 25 (Table 1, entry 8). Based on the data for the pure E-and Z-isomers (entries 7 and 9), the expected yield would have been 35%.

Table 1.

Intramolecular Cyclohexadienone Annulation of Complex 22.a

| ||||||

| entry | complex | n | solvent | % yield 25 b | % yield 26 b | anti-26:syn-26 c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | E-22a | 6 | THF d | — | 18 | 1.3 : 1.0 |

| 2 | E-22a | 6 | MeCN e | — | 22 | 1.8 : 1.0 |

| 3 | E-22a | 6 | Benzene f,g | — | 46 | 1.1 : 1.0 |

| 4 | E-22b | 8 | THF | 45 | ||

| 5 | E-22b | 8 | MeCN | 45 | ||

| 6 | E-22b | 8 | Benzene | 10 | ||

| 7 | Z-22c | 10 | THF | 15 | — h | |

| 8 | Z+E-22c i | 10 | THF | 37 | 14 | 1.0 : 1.0 |

| 9 | E-22c | 10 | THF | 43 | ||

| 10 | E-22c | 10 | MeCN | 64 | ||

| 11 | E-22c | 10 | Benzene | 36 | ||

| 12 | E-22d | 13 | THF | 64 | ||

| 13 | E-22d | 13 | MeCN | 51 | ||

| 14 | E-22d | 13 | Benzene | 32 | ||

Unless otherwise specified, all reactions were carried out at 0.005 M in 22 at 100 °C for 24 h.

Isolated yields after chromatography on silica gel.

The anti isomer is shown and was characterized by X-ray diffraction.

6% yield of trimer isolated.

4% yield of trimer isolated.

13% yield of trimer observed.

Yields were calculated from the weight of a mixture of compounds and ratios determined by HPLC.

Five additional compounds observed in the crude reaction which were not separated and characterized.

71:29 ratio of E:Z isomers.

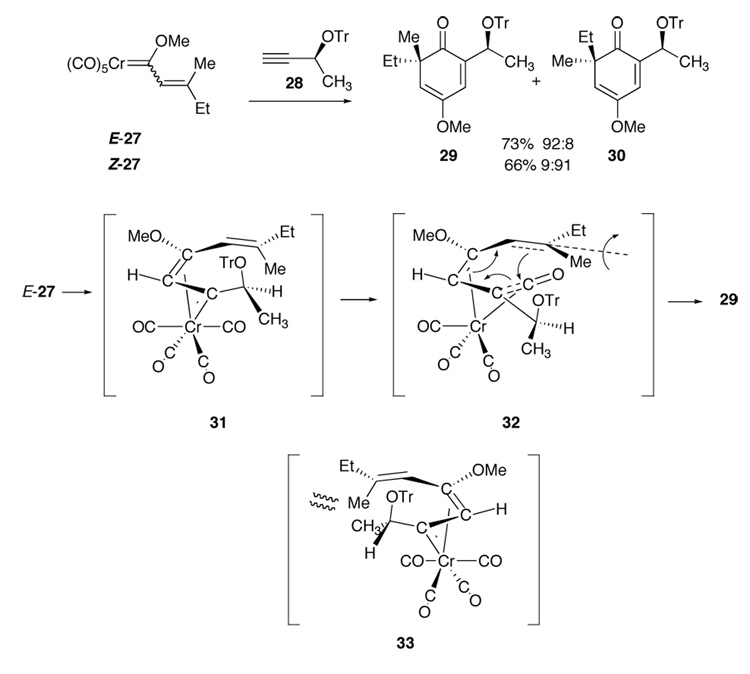

We have previously shown that high levels of 1,4-asymmetric induction could be achieved in the intermolecular cyclohexadienone annulations with propargyl ethers.11 For example, the reaction of the carbene complex 27 with the trityl propargyl ether 28 are stereospecific (Scheme 3). It is thought that the origins of this stereoselectivity derives from a stereoelectronic preference for the propargyl oxygen to be anti to the chromium in the η1,η3-vinyl carbene complexed intermediate which can exist as the two diastereomeric forms 31 and 33 when E-27 was cylized. Of the two, intermediate 31 is expected to be the more stable for steric reasons. Insertion of a CO ligand gives the vinyl ketene complex 32 and then an electrocyclic ring closure with upward movement of the methyl would be expected to avoid close contacts of the methyl group with the chromium and its CO ligands to provide 29 as the major product. Thus cyclization of Z-27 gave the opposite selectivity favoring formation of 30.

Scheme 3.

1,4-Asymmetric Induction in Intermolecular Cyclohexadienone Annulation

A series of carbene complexes 34 were prepared which had ten carbons in the tether and which had a variety of propargyl substituents to determine the extent of 1,4-asymmetric induction in the intramolecular cyclohexadieneone annulation (Table 2). It was no surprise that carbon substituents gave 1:1 mixtures of isomers since this had also been found to be the case for intermolecular benzannulations.13 However, oxygen substiutents were found to give high selectivity in the intermolecular benzannuation13 and cyclohexadienone annulations.11 Clearly, from the data in Table 2, the intramolecularity of the reaction leads to very low stereoselectivities with propargyl oxygen substituents. This is not necessarily a surprise given the geometrical constraints that can be associated with intramolecular processes. The best selectivity of 3:1 was observed with a siloxy group and this is consistent with the increased electron releasing ability of a siloxy group.13,14 This result is significant since it provides for an asymmetric entry to the phomactins via carbene complex 17. The introduction of the proper configuration at the alcohol carbon in 17 would allow for 1,4-asymmetric induction in the 16 and thus to asymmetric syntheses of the phomactins.

Table 2.

1,4-Asymmetric Induction in Intramolecular Cyclohexadienone Annulation.a

| |||||

| entry | complex | R | temp (°C) | % yield 35 + 36 b | 35 : 36 c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | E-34a | OTr | 55 | 65 | 1.0 : 1.1 |

| 2 | 100 | 52 | 1.2 : 1.0 | ||

| 3 | E-34b | OTIPS | 55 | 45 | 3.0 : 1.0 |

| 4 | 100 | 47 | 2.0 : 1.0 | ||

| 5 | E-34c | OMe | 55 | 66 | 2.1 : 1.0 |

| 6 | 100 | 69 | 1.6 : 1.0 | ||

| 7 | E-34d | OMOM | 55 | 44 | 1.0 : 1.1 |

| 8 | 100 | 36 | 1.0 : 1.0 | ||

| 9 | E-34e | t-Bu | 100 | 66 | 1.0 : 1.0 |

| 10 | E-34f | Me | 100 | 94 | 1.0 : 1.2 |

| 11 | E-34g | Ph | 100 | 54 | 1.0 : 1.0 |

Unless otherwise specified, all reactions were carried out at 0.005 M in 34 in THF for 16–24 h.

Isolated yields after chromatography on silica gel.

Ratio determined by 1H NMR. Assignment of relative stereochemistry was made on the basis of an X-ray structure of 35b.

The success of these model systems is quite encouraging for the development of an approach to the phomactins involving a double cyclization of an alkyne tethered carbene complex. Thermolysis of these complexes generates macrocyclic embedded cyclohexadienones and work directed to the synthesis of the phomactins utilizing this process will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures, compound characterization and X-ray data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://www.pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (GM 33589).

References

- 1.(a) Sugano M, Sato A, Iijima Y, Oshima T, Furuya K, Kuwano H, Hata T, Hanzawa H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5463. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chu M, Patel MG, Gullo VP, Truumees I, Puar MS, McPhail AT. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:5817. [Google Scholar]; (c) Chu M, Truumees I, Gunnarsson I, Bishop WR, Kreutner W, Horan AC, Patel MG, Gullo VP, Puar MS. J. Antibiot. 1993;46:554. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sugano M, Sato A, Iijima T, Furuya K, Haruyama H, Yoda K, Hata T. J.Org.Chem. 1994;59:564. [Google Scholar]; (e) Sugano M, Sato A, Ijima T, Furuya K, Kuwano H, Hata T. J. Antibiot. 1995;48:1188. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Koyama K, Ishino M, Takatori K, Sugita T, Kinoshita K, Takahashi K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:6947. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a review of the phomactins, see: Goldring WPD, Pattenden G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:354. doi: 10.1021/ar050186c.

- 3.For studies directed at the synthesis of phomactins, see: Foote KM, Hayes CJ, Pattenden G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:275.Chen D, Wang J, Totah NI. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:1776. doi: 10.1021/jo982488g.Seth PP, Totah NI. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:8750.Seth PP, Totah NI. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2507. doi: 10.1021/ol0061788.Kallan NC, Halcomb RL. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2687. doi: 10.1021/ol0062345.Chemler SR, Danishefsky SJ. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2695. doi: 10.1021/ol0062547.Seth PP, Chen D, Wang J, Gao X, Totah NI. Org. Lett. 2000;56:10185.Foote K, John M, Pattenden G. Synlett. 2001:365.Mi B, Maleczka R. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1491. doi: 10.1021/ol015807q.Chemler SR, Iserloh U, Danishefsky SJ. Org. Lett. 2001;3:2949. doi: 10.1021/ol0161357.Houghton T, Choi S, Rawal VH. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3615. doi: 10.1021/ol0163833.Mohr PJ, Halcomb RL. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2413. doi: 10.1021/ol026159t.Cole K, Hsung RP. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4843. doi: 10.1021/ol030115i.Balnaves AS, McGowan G, Shapland PDP, Thomas EJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:2713.Foote KM, Hayes CJ, John MP, Pattenden G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003;1:3917. doi: 10.1039/b307985f.Cheing JWC, Goldring WPD, Pattenden G. Chem. Commun. 2003:2788. doi: 10.1039/b310753a.Cole KP, Hsung RP. Chem. Commun. 2005:5784. doi: 10.1039/b511338e.Ryu K, Cho Y-S, Jung S-I, Cho C-G. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3343. doi: 10.1021/ol061231z.

- 4.For the total syntheses of phomactins, see: Miyaoka H, Saka Y, Miura S, Yamada Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:7107. Phomactin A.Goldring WPD, Pattenden G. Chem. Commun. 2002:1736. doi: 10.1039/b206041h.Mohr PJ, Halcomb RL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1712. doi: 10.1021/ja0296531.Diaper CM, Goldring WPD, Pattenden G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003;1:3949. doi: 10.1039/b307986d. Phomactin G.Goldring WPD, Pattenden G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:466. doi: 10.1039/b314816e.

- 5.(a) Tokiwano T, Endo T, Tsukagoshi T, Goto H, Fukushi E, Oikawa H. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:2713. doi: 10.1039/b506411b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tokiwano T, Fukushi E, Endo T, Oikawa H. Chem. Commun. 2004:1324. doi: 10.1039/b401377h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dötz KH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1975;14:644. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For reviews on the benzannulation and cyclohexadienone annulations, see: Wulff WD. In: Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry II. Abel EW, Stone RGA, Wilkinson G, editors. Vol. 12. Pergemon Press; 1995. pp. 469–547.Minatti A, Dötz KH. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2004;13:123.Waters ML, Wulff WD. Org. React. in press.

- 8.Tang PC, Wulff WD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:1132. [Google Scholar]

- 9.For reactions tethered through the oxygen on the carbene carbon, see: Semmelhack MF, Bozell JJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:2931.Semmelhack MF, Bozell JJ, Sato T, Wulff W, Spiess EJ, Zask A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:5850.Semmelhack MF, Bozell JJ, Keller L, Sato T, Spiess EJ, Wulff W, Zask A. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:5803.Peterson GA, Kunng F-A, McCallum JS, Wulff WD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:1381.Wulff WD, McCallum JS, Kunng F-A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:7419.Balzer BL, Cazanoue M, Finn MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:8735.Gross MF, Finn MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:10921.Watanabe M, Tanaka K, Saikawa Y, Nakata M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:203.

- 10.For reactions tethered through the alkenyl group on the carbene carbon, see: Wang H, Wulff WD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10573.Dötz KH, Gerhardt A. J. Organomet. Chem. 1999;578:223.Wang H, Wulff WD, Rheingold AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:9862.Dötz KH, Mittenzwey S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002:39.Wang H, Huang J, Wulff WD, Rheingold AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8980. doi: 10.1021/ja035428n.Gopalsamuthiram V, Wulff WD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13936. doi: 10.1021/ja0454236.

- 11.Hsung RP, Quinn JF, Weisenberg BA, Wulff WD, Yap GPA, Rheingold AL. Chem. Commun. 1997:615. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Hsung RP, Wulff WD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:1849. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsung RP, Wulff WD, Rheingold AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:6449. doi: 10.1021/ja010091f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorsbach BA, Prock A, Giering WP. Organometallics. 1995;14:1694. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures, compound characterization and X-ray data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://www.pubs.acs.org.