Abstract

The nuclear hormone receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) is the central regulator of adipogenesis. Although it is the target for several drugs that function as agonist activators, a high affinity endogenous ligand for this receptor that is involved in regulating adipogenesis has yet to be identified. Here, we investigated the requirement for ligand activation of PPARγ in fat cell differentiation, taking advantage of a natural mutant of this receptor that does not bind or become activated by any known natural or synthetic ligand. When ectopically expressed in PPARγ-null fibroblasts, this Q286P allele was able to strongly promote morphological adipogenesis, without any significant difference compared with wild-type PPARγ. In addition, no significant differences were found in the expression of several adipogenic genes between the wild-type and Q286P mutant alleles. To extend our studies to an in vivo setting, we performed subcutaneous injections of PPARγ-expressing fibroblasts into nude mice. We found that both wild-type and Q286P mutant-expressing fibroblasts were able to generate fat pads in the mice. These results suggest that the binding and activation of PPARγ by agonist ligands may not be required for adipogenesis under physiological conditions.

Nuclear hormone receptors, a family of >48 different proteins in humans, are transcription factors that can alter patterns of gene expression in response to extracellular stimuli. Examples include receptors for steroid hormones, vitamin D, and thyroid hormones. Other members of this family, identified on the basis of structural similarities, are so-called orphan receptors: their endogenous ligands are unknown. A subclass of these orphans is the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)2 family, consisting of three members: PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ. These proteins play a critical role in the regulation of energy metabolism and lipid homeostasis in a variety of tissues (for review, see Ref. 1).

PPARγ plays a dominant role in fat tissue development. Its importance was initially suggested by its ability to regulate a fat-specific enhancer of the aP2 gene, an adipocyte-specific lipid-binding protein (2–4). Ectopic expression of PPARγ dramatically promotes the conversion of preadipocytes into fully differentiated adipocytes, including cell growth arrest, triglyceride accumulation, and improved insulin sensitivity (5, 6). In chimeric mouse experiments, cells lacking PPARγ due to genetic ablation did not contribute to the formation of fat tissue, but could form other organs (7). In vitro, PPARγ-null cells, both as stem cells and as fibroblasts, cannot be induced to undergo adipogenesis (7–9). Ectopic expression of PPARγ in these cells restores their adipogenic potential. Dominant-negative versions of PPARγ inhibit the conversion of preadipocytes into adipocytes (10, 11). Mice carrying adipose-specific deletions of the PPARγ gene suffer from lipodystrophy (12, 13). These experiments demonstrated that PPARγ is both necessary and sufficient for adipogenesis. In humans, naturally occurring mutations in PPARγ have also been associated with severe lipodystrophy, further reinforcing the role of this receptor in adipose tissue development (10, 14, 15).

PPARγ is primarily a nuclear protein, binding to DR-1 recognition sites on genomic DNA. Like many other nuclear hormone receptors, it functions as an obligate heterodimer with retinoid X receptors. PPARγ shares structural similarities with its family members, most notably a C-terminal ligand-binding domain with a hydrophobic pocket, terminated by an α-helix, termed an AF-2 domain, which serves as a docking platform for co-activator binding. In the classic “mousetrap” model of nuclear hormone receptor function, binding of an agonist to the ligand-binding domain causes a structural shift that alters the position of the AF-2 domain in such a way that co-activator binding is enhanced (reviewed in Ref. 16). Several structurally distinct agonists for PPARγ have been described. These include the antidiabetic thiazolidinedione drugs, including troglitazone, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, which function as agonist ligands of PPARγ with binding affinities in the mid-nanomolar range (17). In fact, it is most likely that these drugs act primarily by activating PPARγ in adipose tissue. In addition, N-aryl tyrosine derivatives can act as powerful agonists of PPARγ (18).

However, a high affinity endogenous ligand has yet to be isolated and identified as playing a physiological role in adipogenesis. Fatty acids, especially polyunsaturates and their derivatives, can act PPARγ ligands. Most notably, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 is a powerful PPARγ agonist (19, 20). However, the biological relevance of these compounds as PPARγ ligands remains unclear.

Outside of its role in adipogenesis, PPARγ has been implicated as a tumor suppressor (21–23). A screen of human colon cancer samples revealed a mutation in PPARγ, Q286P, in the backbone helix of the ligand-binding domain (24). The corresponding mutant protein is unable to bind to either thiazolidinediones or 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2. Therefore, this version of the receptor became an important tool to determine the role of ligand binding in the adipogenic function of PPARγ. In this study, we show that PPARγ Q286P, although resistant to ligand activation, is fully adipogenic. These results surprisingly suggest that ligand binding is not a requirement for PPARγ function in fat cell differentiation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Transcription Reporter Assays—293 cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 1.5 × 105 cells/well. The following day, the cells were transfected using SuperFect (Qiagen Inc.) following the manufacturer's instructions. Each well contained 50 ng of pDR-1 (3×, based on the UCP1 PPARγ recognition site)-luciferase reporter plasmid, 250 ng of pMSCV-PPARγ expression plasmid, and 25 ng of pRL-renillin plasmid for normalization. Following an overnight transfection, the cells were treated with PPARγ-activating ligands (or dimethyl sulfoxide as a control) for 24 h. The cells were harvested and lysed in Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega), and 15 μl of each lysate was assayed for luciferase and renillin activity with the Dual-Luciferase kit (Promega). Luciferase activity was normalized to renillin activity. Each treatment was carried out in triplicate.

Retroviral Infection and Differentiation of Cells—PPARγ-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (8) were cultured in Dulbec-co's modified Eagle's medium and 10% fetal bovine serum. Retroviruses expressing FLAG-HA-PPARγ, FLAG-HA-PPARγ Q286P, and FLAG-HA-PPARγ E499Q were produced by standard methods using the pMSCV plasmid (Clontech). Following infection of the cells with the retrovirus, cells expressing the ectopic protein were selected by incubation with 2 μg/ml puromycin. The fibroblasts were grown to confluence and then subjected to a hormone mixture to induce adipogenic differentiation. This treatment consisted of 1 μm dexamethasone, 0.5 mm isobutylmethylxanthine, and 5 μg/ml insulin for 48 h, followed by 5 μg/ml insulin for the remaining course of differentiation. Lipid accumulation in the cells was detected by Oil Red O staining.

Immunoblotting—Cells grown on 10-cm culture dishes were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and then harvested in 0.5 ml of high salt lysis buffer (400 mm KCl, 20 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitors). The cells were lysed for 30 min on ice and then microcentrifuged to remove debris. Protein content was determined by a BCA assay (Pierce), and 25-μg aliquots were subjected to SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and blotted with an anti-PPARγ monoclonal antibody (1:200 dilution; E8, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Blots were developed using SuperSignal West Dura reagents (Pierce) and autoradiographed to detect PPARγ protein.

Measurement of Adipogenic Gene Expression—Cells were grown to confluence and then induced to undergo differentiation using the hormone mixture described above. At each day of differentiation, total RNA was purified from cells using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The RNA was reverse-transcribed, and the levels of adipogenic mRNAs were measured by real-time PCR using the SYBR reagent (Applied Biosystems). Expression was normalized to 18 S RNA levels. The PCR primers used are listed in the supplemental table.

In Vivo Generation of Adipocytes—PPARγ-null cells ectopically expressing the different PPARγ mutants (as described above) were cultured on 15-cm plates at low density, trypsinized, and counted. 200-μl aliquots of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 1 × 107 cells were implanted subcutaneously at the sterna of male NU/NU-nuBr athymic “nude” mice. 6 weeks after injection, mice were killed, and the skin covering the sternum was removed and inspected for the presence of a fat pad. Cross-sections of this skin were fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin by standard methods.

RESULTS

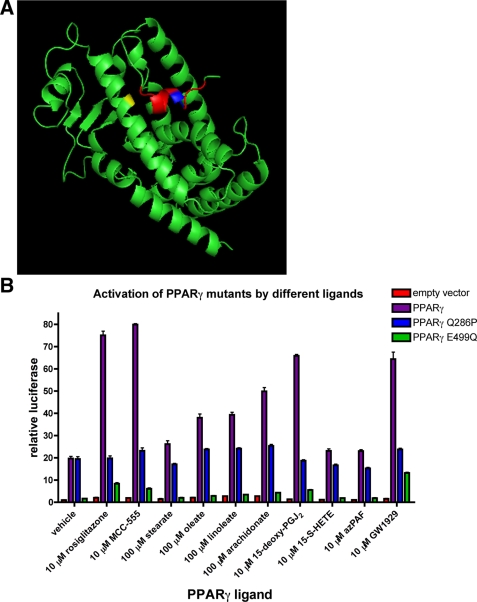

The Q286P Mutant of PPARγ Is Not Activated by Known Agonists—As a nuclear hormone receptor, PPARγ contains a canonical ligand-binding domain at its C terminus. A screen of human colon cancer samples revealed a mutation that results in a glutamine-to-proline mutation at residue 286 of the protein (24). According to published crystal structures, this mutation occurs in the middle of α-helix 3 of the ligand-binding domain, which forms the backbone of the ligand-binding pocket (Fig. 1A) (25).

FIGURE 1.

The PPARγ Q286P mutant is resistant to ligand activation. A, shown is the crystal structure of the apo-PPARγ ligand-binding domain, indicating the locations of relevant mutations. Q286P is shown in yellow, and E499Q is shown in blue. Helix 12, containing the AF-2 domain, is shown in red. The figure was generated by the PyMOL program (DeLano Scientific) using data from Ref. 25. B, 293 cells were transfected with PPARγ mutant expression plasmids along with a DR-1-luciferase reporter plasmid. The transfected cells were treated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of the different known PPARγ-activating ligands and then harvested and assayed for luciferase activity. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. of three separate cell preparations. Data are expressed as relative activity based on non-PPARγ-expressing and non-agonist-treated cells and are normalized to cotransfected renillin expression. 15-deoxy-PGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; 15-S-HETE, 15-S-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; azPAF, 1-O-hexadecyl-2-azelaoylphosphatidylcholine.

Initial characterization of PPARγ Q286P suggested that this mutant was unable to bind to and be activated by some PPARγ ligands (24). We have extended these studies to demonstrate that the Q286P mutation renders PPARγ impervious to activation by virtually all known agonists. PPARγ agonists fall into three structurally distinct categories: thiazolidinediones (including the antidiabetic drug rosiglitazone), fatty acids and their oxidized derivatives, and N-aryl tyrosine derivatives. The ability of these compounds to activate PPARγ was tested in transcription assays based on PPARγ expression with a DR-1-luciferase reporter (Fig. 1B). As expected, wild-type PPARγ was activated by agonists from all three classes. However, PPARγ Q286P produced no significant activation when treated with any of the agonists. Interestingly, without agonist treatment, wild-type PPARγ and PPARγ Q286P both displayed significant and similar transcriptional activity.

Like other nuclear hormone receptors, the C-terminal α-helix of the ligand-binding domain contains the AF-2 activation region. This domain serves as a docking site for PPARγ co-activators. Disruption of this α-helix by introducing a glutamate-to-glutamine mutation at residue 499 renders PPARγ resistant to rosiglitazone activation (26). PPARγ E499Q was also resistant to activation by other agonists (Fig. 1B). In addition, PPARγ E499Q displayed a much lower level of basal transcriptional activity compared with wild-type PPARγ or PPARγ Q286P.

PPARγ Q286P Is Fully Adipogenic—Previous experiments have shown that immortalized fibroblasts derived from embryonic mice lacking PPARγ are completely unable to differentiate into adipocytes (8). However, ectopic expression of PPARγ in these fibroblasts restores their adipogenic potential. Therefore, we used these PPARγ-null cells to test the ability of the Q286P mutant to induce adipogenesis because the confounding effects of the endogenous PPARγ protein would be avoided.

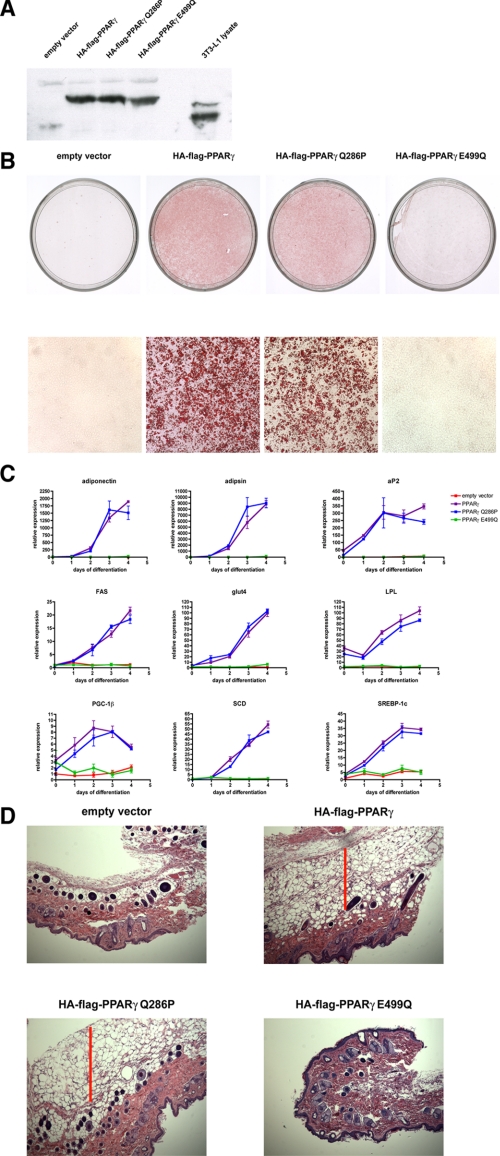

Retroviruses expressing wild-type PPARγ, PPARγ Q286P, and PPARγ E499Q were used to infect PPARγ-null cells. Expression of the proteins was detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 2A), and all three PPARγ proteins were expressed at levels equivalent to those seen in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

FIGURE 2.

The PPARγ Q286P mutant is fully adipogenic. PPARγ-null fibroblasts were infected with retrovirus expressing 1) no ectopic protein, 2) wild-type PPARγ, 3) PPARγ Q286P, or 4) PPARγ E499Q. All ectopic PPARγ constructs were dual-tagged at the N terminus with FLAG and HA epitopes. The cells were induced to undergo adipogenic differentiation with the dexamethasone/isobutylmethylxanthine/insulin hormone mixture (described under “Experimental Procedures”). A, shown is an immunoblot for PPARγ. Whole cell extracts were prepared from retrovirally infected cells as well as from fully differentiated adipocytes. Following SDS-PAGE, the extracts were immunoblotted for PPARγ. B, following 6 days of differentiation, the cells were stained with Oil Red O to detect lipid accumulation. C, at consecutive days of differentiation, cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted. The expression levels of the adipogenic markers indicated in the figure were measured by real-time PCR. Each point is the mean ± S.E. of three separate cell preparations. FAS, fatty acid synthase; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; SCD, stearoyl-CoA desaturase. D, PPARγ-null fibroblasts expressing ectopic PPARγ mutants were injected subcutaneously into the sternal regions of athymic nude mice. After 6 weeks, the skin covering the sternum was removed and examined for the presence of a subcutaneous fat pad. Skin cross-sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined for the presence of fat cells (indicated by a red bar).

Following infection, cells were grown to confluence and then induced to undergo differentiation using a standard hormone treatment consisting of insulin, a glucocorticoid, and a cAMP phosphodiesterase inhibitor. As expected, control cells infected with an empty viral vector showed no lipid accumulation associated with adipogenesis (Fig. 2B). Cells expressing wild-type PPARγ demonstrated a large lipid accumulation, as evidenced by the red color produced by Oil Red O staining. Surprisingly, cells ectopically expressing the PPARγ Q286P mutant also accumulated extensive amounts of lipid when exposed to the hormone differentiation mixture. The lipid levels in wild-type PPARγ and PPARγ Q286P cells appeared to be virtually identical. Conversely, the PPARγ-null cells ectopically expressing PPARγ E499Q were completely resistant to lipid accumulation following hormone treatment. These data suggest that a functional AF-2 domain in PPARγ is still required for adipogenesis.

To determine the adipogenic potential of PPARγ Q286P at a molecular level, the expression of mRNAs characteristic of mature fat cells was followed during the time course of differentiation. These mRNAs encode proteins involved in transcriptional control (SREBP-1c (sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c), PGC-1β (PPARγ co-activator-1β)), lipid synthesis (fatty acid synthase, stearoyl-CoA desaturase), lipid uptake (lipoprotein lipase, aP2), insulin action (Glut4 (glucose transporter-4)), and the “endocrine” function of adipocytes (adiponectin, adipsin). In every case, these mRNA levels in PPARγ Q286P cells closely matched those seen in wild-type PPARγ cells (Fig. 2C). Therefore, there appeared to be no significant molecular differences between adipocytes produced by wild-type PPARγ and those produced by PPARγ with a mutant ligand-binding domain. However, PPARγ E449Q was unable to induce expression of any of these characteristic adipocyte mRNAs, again confirming the requirement for a functional AF-2 domain in the receptor for adipogenesis.

The ability of PPARγ Q286P to induce adipogenesis in cell culture led us to question whether a similar effect could be seen in vivo, where differentiation would be regulated more physiologically rather than as a response to an artificial hormone treatment. Previous experiments have shown that the subcutaneous injection of undifferentiated preadipocytes into immunocompromised nude mice can result in the formation of a distinct fat pad (27, 28). Therefore, we injected the cells ectopically expressing these different PPARγ mutants into the skin above the sterna of nude mice (where there is little naturally occurring subcutaneous fat). 6 weeks after the injection, mice injected with cells expressing the wild-type PPARγ protein formed a distinct fat pad around the site of injection (Fig. 2D). Notably, a similar effect was seen with cells expressing the PPARγ Q286P protein. The fat pads from the wild-type PPARγ cells and the PPARγ Q286P cells expressed equivalent levels of aP2 mRNA, characteristic of mature adipocytes (data not shown). Cells without PPARγ and cells expressing the PPARγ E499Q protein were unable to form a fat pad when injected into the immunocompromised mice. These results suggest that a mutant ligand-binding domain that lacks a functional response to known ligands is not required for adipogenesis in response to either a hormone mixture or normal physiological signals. Nevertheless, an intact AF-2 domain is still required for adipogenesis in vivo.

DISCUSSION

Despite intense efforts, the identity of a high affinity endogenous ligand for PPARγ that regulates adipogenesis remains unknown. Soon after the role of PPARγ in adipogenesis was first recognized (5), 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 was identified as a powerful natural agonist for this receptor (19, 20). However, it is doubtful that there is a biologically sufficient level of this prostanoid present in adipocytes. Polyunsaturated fatty acids can also activate PPARγ, albeit weakly. Therefore, these lipids are often invoked as a potential endogenous PPARγ ligand, but direct evidence for this is lacking. Fatty acid derivatives such as lysophosphatidic acid (29, 30) and nitrolinoleic acid (31) can also act as PPARγ agonists. Oxidized lipids such as hydroxylated fatty acids 1-O-hexadecyl-2-azelaoylphosphatidylcholine (33) can activate PPARγ. However, the role that any of these compounds play in the development of adipocytes is not known.

This lack of success in identifying biologically relevant agonists led us to investigate whether the binding of a ligand to PPARγ is, in fact, required for this receptor's adipogenic activity. To test this notion, we took advantage of a naturally occurring PPARγ mutant that contains a glutamine-to-proline shift in the α-helix backbone of the ligand-binding domain. The introduction of a proline into an α-helix introduces a bend in the secondary structure (34). The orientation and rotation of the post-proline α-helix are also shifted. In addition, Gln286 has been directly implicated in at least some ligand-binding structures (25, 35). When tested for its ability to respond to PPARγ agonists, the Q286P mutant was completely resistant, making it an ideal tool for investigating the importance of ligand binding for PPARγ function.

Surprisingly, when tested for its ability to promote adipogenesis, the PPARγ Q286P protein proved to be just as competent as its wild-type counterpart. No significant differences were observed in either morphological or gene expression or lipid characteristics of differentiation. In vivo, the PPARγ Q286P-expressing fibroblasts were able to differentiate into adipocytes. These results suggest that a functional ligand-binding domain, as defined by normal criteria, is not necessary for the adipogenic function of PPARγ.

These data can be interpreted in several different ways. First, it is possible that PPARγ binds a ligand, both in cell culture and in vivo, in such a way that it can still activate the Q286P form of the receptor protein. Such a ligand is not known but cannot be entirely ruled out. Second, it is possible that a ligand is present during adipogenesis but produces a quantitative rather than qualitative effect. In the experiments presented here, PPARγ protein was expressed at levels equivalent to those seen in mature adipocytes rather than at levels found in preadipocytes, which are 10–20-fold lower. Because differentiation is initiated in preadipocytes, the higher levels of PPARγ protein expressed in our experiments may relieve the requirement for ligand activation. Last, although wild-type PPARγ may contain ligand-binding activity, it may not be required for the process of adipogenesis. The hormone treatment required to stimulate fat cell differentiation through PPARγ may trigger the induction of a co-activator protein. Although many co-activators require ligand binding to allow receptor docking, others, such as PGC-1α and pCAF, can activate nuclear hormone receptors, including PPARγ, in the absence of ligand binding. The ability to distinguish between these explanations will require further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Spiegelman laboratory for helpful discussions, especially Drs. J. Ruas, W. Yang, S. Jäger, and S. Blättler. PPARγ-null fibroblasts were the gift of Dr. E. Rosen.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK31405. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a supplemental table.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; HA, hemagglutinin.

References

- 1.Feige, J. N., Gelman, L., Michalik, L., Desvergne, B., and Wahli, W. (2006) Prog. Lipid Res. 45 120–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graves, R. A., Tontonoz, P., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1992) Mol. Cell. Biol. 12 1202–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tontonoz, P., Graves, R. A., Budavari, A. I., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Lui, M., Hu, E., Tempst, P., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22 5628–5634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tontonoz, P., Hu, E., Graves, R. A., Budavari, A. I., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1994) Genes Dev. 8 1224–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tontonoz, P., Hu, E., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1994) Cell 79 1147–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altiok, S., Xu, M., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1997) Genes Dev. 11 1987–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen, E. D., Sarraf, P., Troy, A. E., Bradwin, G., Moore, K., Milstone, D. S., Spiegelman, B. M., and Mortensen, R. M. (1999) Mol. Cell 4 611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosen, E. D., Hsu, C. H., Wang, X., Sakai, S., Freeman, M. W., Gonzalez, F. J., and Spiegelman, B. M. (2002) Genes Dev. 16 22–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubota, N., Terauchi, Y., Miki, H., Tamemoto, H., Yamauchi, T., Komeda, K., Satoh, S., Nakano, R., Ishii, C., Sugiyama, T., Eto, K., Tsubamoto, Y., Okuno, A., Murakami, K., Sekihara, H., Hasegawa, G., Naito, M., Toyoshima, Y., Tanaka, S., Shiota, K., Kitamura, T., Fujita, T., Ezaki, O., Aizawa, S., Nagai, R., Tobe, K., Kimura, S., and Kadowaki, T. (1999) Mol. Cell 4 597–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barroso, I., Gurnell, M., Crowley, V. E., Agostini, M., Schwabe, J. W., Soos, M. A., Maslen, G. L., Williams, T. D., Lewis, H., Schafer, A. J., Chatterjee, V. K., and O'Rahilly, S. (1999) Nature 402 880–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger, J., Patel, H. V., Woods, J., Hayes, N. S., Parent, S. A., Clemas, J., Leibowitz, M. D., Elbrecht, A., Rachubinski, R. A., Capone, J. P., and Moller, D. E. (2000) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 162 57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He, W., Barak, Y., Hevener, A., Olson, P., Liao, D., Le, J., Nelson, M., Ong, E., Olefsky, J. M., and Evans, R. M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 15712–15717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai, T., Takakuwa, R., Marchand, S., Dentz, E., Bornert, J. M., Messaddeq, N., Wendling, O., Mark, M., Desvergne, B., Wahli, W., Chambon, P., and Metzger, D. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 4543–4547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hegele, R. A., Cao, H., Frankowski, C., Mathews, S. T., and Leff, T. (2002) Diabetes 51 3586–3590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agostini, M., Schoenmakers, E., Mitchell, C., Szatmari, I., Savage, D., Smith, A., Rajanayagam, O., Semple, R., Luan, J., Bath, L., Zalin, A., Labib, M., Kumar, S., Simpson, H., Blom, D., Marais, D., Schwabe, J., Barroso, I., Trembath, R., Wareham, N., Nagy, L., Gurnell, M., O'Rahilly, S., and Chatterjee, K. (2006) Cell Metab. 4 303–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moras, D., and Gronemeyer, H. (1998) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10 384–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehmann, J. M., Moore, L. B., Smith-Oliver, T. A., Wilkison, W. O., Willson, T. M., and Kliewer, S. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 12953–12956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown, K. K., Henke, B. R., Blanchard, S. G., Cobb, J. E., Mook, R., Kaldor, I., Kliewer, S. A., Lehmann, J. M., Lenhard, J. M., Harrington, W. W., Novak, P. J., Faison, W., Binz, J. G., Hashim, M. A., Oliver, W. O., Brown, H. R., Parks, D. J., Plunket, K. D., Tong, W. Q., Menius, J. A., Adkison, K., Noble, S. A., and Willson, T. M. (1999) Diabetes 48 1415–1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forman, B. M., Tontonoz, P., Chen, J., Brun, R. P., Spiegelman, B. M., and Evans, R. M. (1995) Cell 83 803–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kliewer, S. A., Lenhard, J. M., Willson, T. M., Patel, I., Morris, D. C., and Lehmann, J. M. (1995) Cell 83 813–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueller, E., Sarraf, P., Tontonoz, P., Evans, R. M., Martin, K. J., Zhang, M., Fletcher, C., Singer, S., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1998) Mol. Cell 1 465–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mueller, E., Smith, M., Sarraf, P., Kroll, T., Aiyer, A., Kaufman, D. S., Oh, W., Demetri, G., Figg, W. D., Zhou, X. P., Eng, C., Spiegelman, B. M., and Kantoff, P. W. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 10990–10995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girnun, G. D., Smith, W. M., Drori, S., Sarraf, P., Mueller, E., Eng, C., Nambiar, P., Rosenberg, D. W., Bronson, R. T., Edelmann, W., Kucherlapati, R., Gonzalez, F. J., and Spiegelman, B. M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 13771–13776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarraf, P., Mueller, E., Smith, W. M., Wright, H. M., Kum, J. B., Aaltonen, L. A., de la Chapelle, A., Spiegelman, B. M., and Eng, C. (1999) Mol. Cell 3 799–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nolte, R. T., Wisely, G. B., Westin, S., Cobb, J. E., Lambert, M. H., Kurokawa, R., Rosenfeld, M. G., Willson, T. M., Glass, C. K., and Milburn, M. V. (1998) Nature 395 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hauser, S., Adelmant, G., Sarraf, P., Wright, H. M., Mueller, E., and Spiegelman, B. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 18527–18533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandrup, S., Loftus, T. M., MacDougald, O. A., Kuhajda, F. P., and Lane, M. D. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 4300–4305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green, H., and Kehinde, O. (1979) J. Cell. Physiol. 101 169–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, C., Baker, D. L., Yasuda, S., Makarova, N., Balazs, L., Johnson, L. R., Marathe, G. K., McIntyre, T. M., Xu, Y., Prestwich, G. D., Byun, H. S., Bittman, R., and Tigyi, G. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 199 763–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McIntyre, T. M., Pontsler, A. V., Silva, A. R., St. Hilaire, A., Xu, Y., Hinshaw, J. C., Zimmerman, G. A., Hama, K., Aoki, J., Arai, H., and Prestwich, G. D. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 131–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schopfer, F. J., Lin, Y., Baker, P. R., Cui, T., Garcia-Barrio, M., Zhang, J., Chen, K., Chen, Y. E., and Freeman, B. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 2340–2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagy, L., Tontonoz, P., Alvarez, J. G., Chen, H., and Evans, R. M. (1998) Cell 93 229–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies, S. S., Pontsler, A. V., Marathe, G. K., Harrison, K. A., Murphy, R. C., Hinshaw, J. C., Prestwich, G. D., St., Hilaire, A., Prescott, S. M., Zimmerman, G. A., and McIntyre, T. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 16015–16023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visiers, I., Braunheim, B. B., and Weinstein, H. (2000) Protein Eng. 13 603–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gampe, R. T., Jr., Montana, V. G., Lambert, M. H., Miller, A. B., Bledsoe, R. K., Milburn, M. V., Kliewer, S. A., Willson, T. M., and Xu, H. E. (2000) Mol. Cell 5 545–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.