Abstract

The integral membrane enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) hydrolyzes the endocannabinoid anandamide and related amidated signaling lipids. Genetic or pharmacological inactivation of FAAH produces analgesic, anxiolytic, and antiinflammatory phenotypes but not the undesirable side effects of direct cannabinoid receptor agonists, indicating that FAAH may be a promising therapeutic target. Structure-based inhibitor design has, however, been hampered by difficulties in expressing the human FAAH enzyme. Here, we address this problem by interconverting the active sites of rat and human FAAH using site-directed mutagenesis. The resulting humanized rat (h/r) FAAH protein exhibits the inhibitor sensitivity profiles of human FAAH but maintains the high-expression yield of the rat enzyme. We report a 2.75-Å crystal structure of h/rFAAH complexed with an inhibitor, N-phenyl-4-(quinolin-3-ylmethyl)piperidine-1-carboxamide (PF-750), that shows strong preference for human FAAH. This structure offers compelling insights to explain the species selectivity of FAAH inhibitors, which should guide future drug design programs.

Keywords: anandamide, crystal structure, endocannabinoid, fatty acid amides, hydrolase

Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) is an integral membrane enzyme that hydrolyzes the fatty acid amide class of lipid transmitters (1, 2). FAAH substrates include the endogenous cannabinoid N-arachidonoyl ethanolamine (anandamide) (3), the antiinflammatory factor N-palmitoyl ethanolamine (PEA) (4), the sleep-inducing substance 9(Z)-octadecenamide (oleamide) (5), and the satiating signal N-oleoyl ethanolamine (OEA) (6). FAAH inactivation by either chemical inhibition or genetic deletion of the FAAH gene leads to elevated endogenous levels of fatty acid amides and a range of behavioral effects that include analgesia (7–12), anxiolytic (8, 13, 14), antidepressant (13, 15), sleep-enhancing (16), and antiinflammatory (17–19) phenotypes. Importantly, these behavioral phenotypes occur in the absence of alterations in motility, weight gain, or body temperature that are typically observed with direct cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) agonists. Inhibition of FAAH thus may offer an attractive way to produce the therapeutically beneficial phenotypes of activating the endocannabinoid system without the undesirable side effects that are observed with direct CB1 agonists.

FAAH is a member of a large class of enzymes termed the amidase signature class (20). These enzymes, which span all kingdoms of life, use an unusual Ser–Ser–Lys catalytic triad (21, 22) to hydrolyze amide bonds on a wide range of small-molecule substrates. Despite their atypical catalytic mechanism, amidase signature enzymes are inactivated by general classes of serine hydrolase inhibitors [e.g., trifluoromethyl ketones (23, 24), fluorophosphonates (25), α-ketoheterocycles (26), carbamates (8, 27)]. First-generation FAAH inhibitors, such as methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP) (25), were substrate-derived in structure and therefore lack selectivity for FAAH relative to other lipid hydrolases. More recently, FAAH inhibitors with greatly improved selectivity have been described (24, 26, 28). However, the mechanism by which these inhibitors achieve potency and selectivity for FAAH remains unknown, due in large part to a dearth of structural information on enzyme–inhibitor complexes. Indeed, to date, only a single crystal structure of FAAH has been reported, a complex between the rat enzyme (rFAAH) and MAFP (22). Efforts to date to achieve structural information on the human FAAH (hFAAH) protein have been hampered by low-expression yields in recombinant systems and problematic biochemical properties (i.e., instability, aggregation). Here, we describe an alternative strategy that involves the mutagenic interconversion of the rat and hFAAH active sites. Specifically, we have engineered a “humanized” rat (h/r) FAAH that contains a complete human active site within the parent rat protein. This h/rFAAH exhibits the inhibitor sensitivity profile of hFAAH while maintaining the high-recombinant expression yields and biochemical properties of the rat enzyme. We exploit these unique features to solve the crystal structure of h/r FAAH in complex with a selective small-molecule inhibitor. This structure reveals how inhibitors achieve potency and specificity for hFAAH, thus offering key insights to guide future drug design efforts.

Results

Engineering a Humanized Form of Rat FAAH.

We have previously reported an Escherichia coli expression system to produce purified, active rFAAH protein bearing a His6 affinity tag in place of the N-terminal transmembrane domain of the enzyme (29). This recombinant protein was used to determine the crystal structure of FAAH in complex with the general serine hydrolase inhibitor MAFP (22). hFAAH, despite sharing ≈82% sequence identity with rFAAH, has proven more difficult to express and purify. There are only a few reports on the recombinant expression of hFAAH using baculovirus–insect cell (30, 31) and bacterial (30) systems; however, in these cases, hFAAH expression levels were not reported. Our own efforts to optimize fully the recombinant expression of FAAH proteins in E. coli have resulted in a robust protocol to generate high yields of rFAAH (≈20 mg of purified enzyme per liter of culture). Although this protocol also produced a modest quantity of hFAAH (≈1 mg of purified protein per liter of culture), this protein was much less stable and more prone to aggregation than rFAAH.

As an alternative strategy, we sought to create a humanized version of rFAAH, where the active site of the protein was converted to match the human enzyme. Active-site residues were identified based on the crystal structure of rFAAH (22), and sequence comparisons identified six of these amino acids that differed between rFAAH (L192, F194, A377, S435, I491, and V495) and hFAAH (F192, Y194, T377, N435, V491, and M495) [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. In the rFAAH structure, all of these residues except S435 interact with the arachidonyl chain of the bound methyl arachidonyl phosphonate (MAP), the MAFP inhibitor adduct. S435 was found to be in close proximity to, but not directly contacting, the arachidonyl chain. We mutated each of these 6 aa in rFAAH to the corresponding residues in hFAAH, generating a h/rFAAH protein that expressed at levels similar to rFAAH in E. coli (≈10 mg of purified protein per liter of culture).

hFAAH and h/rFAAH Show Similar Catalytic Properties and Inhibitor Sensitivity.

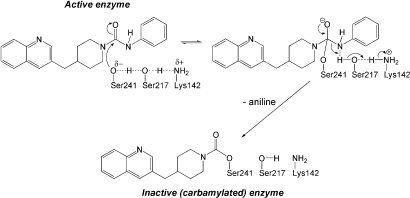

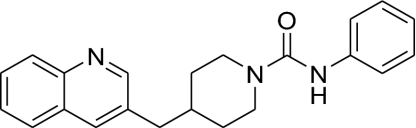

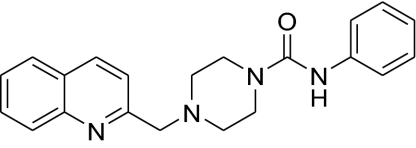

Kinetic constants for hydrolysis of the substrate oleamide were determined to compare the catalytic efficiencies of hFAAH, rFAAH, and h/rFAAH (Table 1). The three FAAH variants displayed Km and kcat values that were all within a factor of 2 of each other, indicating that the enzymes exhibit similar catalytic efficiencies. Despite their equivalent catalytic properties, hFAAH and rFAAH displayed substantial differences in their inhibitor sensitivity profiles. For instance, the piperidine urea inhibitor N-phenyl-4-(quinolin-3-ylmethyl)piperidine-1-carboxamide (PF-750) (Table 2), which inhibits FAAH by covalent carbamylation of the catalytic S241 nucleophile (28) (Fig. 1), was 7.6-fold more potent for hFAAH compared with rFAAH (Table 2). An expanded set of analogs of PF-750 also consistently showed greater potency for the hFAAH enzyme (Table 2). In contrast, the reversible α-ketoheterocycle inhibitor OL-135 (9) was a superior inhibitor of rFAAH (Table 3). The inhibitor sensitivity profile of h/rFAAH was strikingly similar to that of hFAAH for all compounds examined (Tables 2 and 3), confirming that the active site of the former protein more closely resembles the human enzyme. These data indicate that h/rFAAH is a good surrogate for investigating the interactions of either reversible or irreversible inhibitors with the hFAAH enzyme.

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetic parameters of hFAAH, rFAAH, and h/rFAAH

| FAAH | Km, μM | kcat, s−1 | kcat/Km, M−1 s−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| hFAAH | 23.6 ± 2.10 | 1.74 ± 0.31 | 7.37 × 104 |

| rFAAH | 38.7 ± 2.70 | 3.16 ± 0.36 | 8.17 × 104 |

| h/rFAAH | 38.1 ± 7.77 | 2.90 ± 0.45 | 7.61 × 104 |

Values are averages ± SD of two independent experiments.

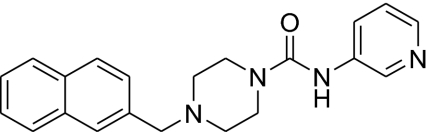

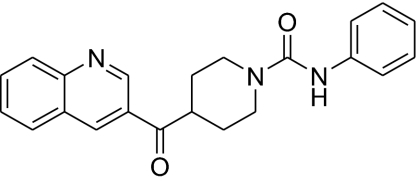

Table 2.

Potencies of FAAH inhibitors for hFAAH, rFAAH, and h/rFAAH: kinact/KI values

| Compound | Structures |

kinact/KI, M−1s−1 |

Potency ratio |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hFAAH | rFAAH | h/rFAAH | hFAAH/rFAAH | ||

| 1(PF-750) |  |

791 ± 34 | 104 ± 14 | 528 ± 53 | 7.6 |

| 2(PF-622) |  |

621 ± 130 | 154 ± 67 | 623 ± 250 | 4.0 |

| 3 |  |

2,110 ± 230 | 322 ± 120 | 1,960 ± 1,100 | 6.6 |

| 4 |  |

468 ± 53 | 18.2 ± 8.2 | 415 ± 65 | 26 |

| 5 |  |

1,520 ± 340 | 362 ± 32 | 1,300 ± 590 | 4.2 |

kinact/KI values were determined as described in Methods and by using Km values shown in Table 1. The concentrations of inhibitors varied from 0.012 to 25 μM. Values are averages ± SD of two independent experiments.

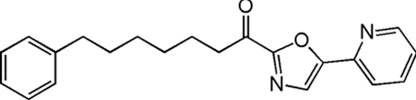

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of covalent inhibition of FAAH by PF-750. The catalytic triad Ser–Ser–Lys is shown.

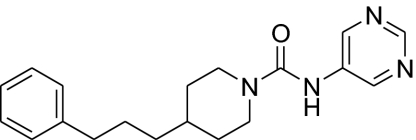

Table 3.

Potencies of FAAH inhibitors for hFAAH, rFAAH, and h/rFAAH: IC50 values

| Compound | Structure | IC50, nM |

IC50 ratio |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hFAAH | rFAAH | h/rFAAH | hFAAH/rFAAH | ||

| OL-135 |  |

208 ± 35 | 47.3 ± 2.9 | 420 ± 15 | 4.4 |

IC50 values were measured with 15–25 nM FAAH as described in ref. 28. The concentrations of inhibitors varied from 0.0001 to 100 μM. Data were plotted as percentage of inhibition vs. inhibitor concentration and fit to the equation y = 100/[1 + (x/IC50)z], using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software), where IC50 is the inhibitor concentration at 50% inhibition and z is the Hill slope. Values are averages ± SD for two independent experiments.

Crystal Structure of a PF-750 Inhibitor–h/rFAAH Complex.

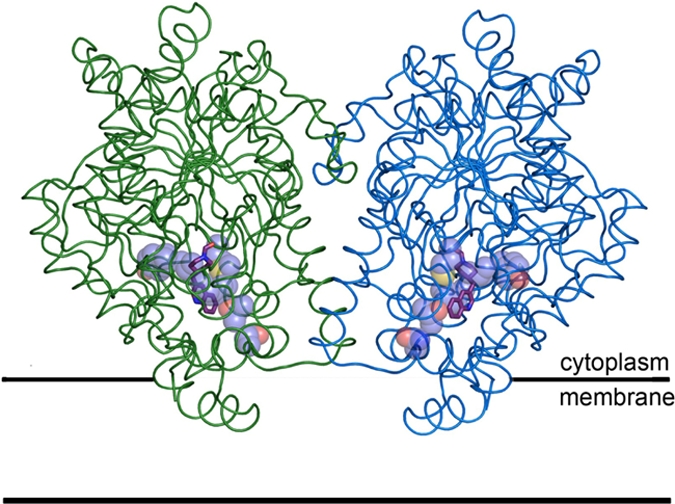

To gain insights into the active-site features responsible for the disparate inhibitor sensitivity profiles of hFAAH and rFAAH, we determined the crystal structure of the h/rFAAH protein bound to PF-750. The structure was determined at 2.75-Å resolution in the presence of the detergent n-decyl-β-d-maltoside to maintain protein stability and solubility. The overall fold of h/rFAAH was essentially identical to rFAAH (22), with both enzymes crystallizing as a dimer and each monomer characterized by 11 β-strands surrounded by 24 α-helices of various lengths (Fig. 2). Considering that the original rFAAH structure was determined in the presence of a distinct detergent [N,N-dimethyldodecylamine N-oxide (LDAO)], these findings indicate that the structure of FAAH is not particularly sensitive to the type of detergent used for enzyme solubilization and crystallization.

Fig. 2.

Structure of the h/rFAAH protein bound to PF-750 inhibitor (purple sticks) and modeled to integrate into the membrane in a monotopic manner. The monomeric subunits of the FAAH dimer have been distinguished with green and blue coloring. Humanized residues are shown as violet spheres (carbon in violet, oxygen in red, and sulfur in yellow).

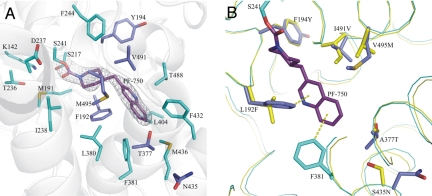

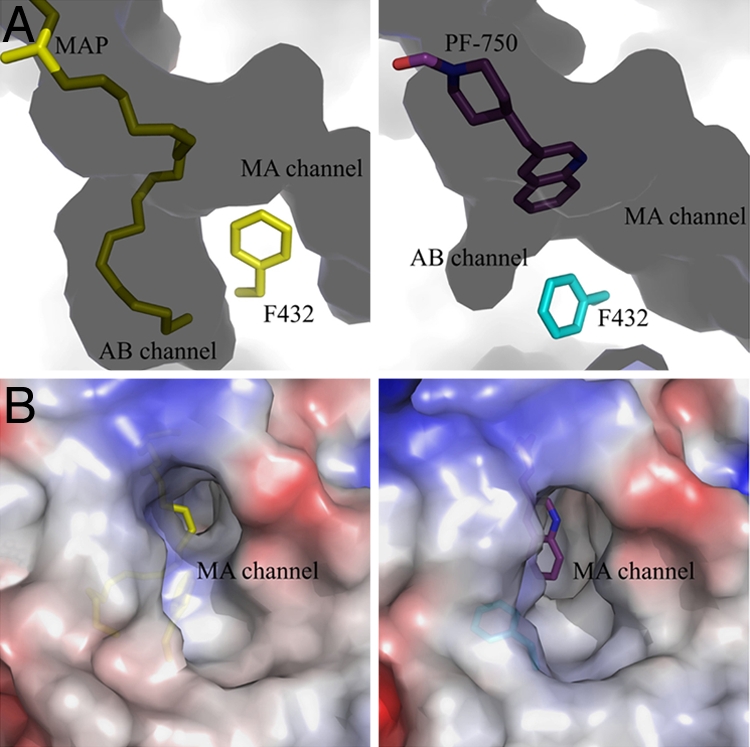

The PF-750 inhibitor showed well defined electron density in the h/rFAAH active site (Fig. 3A). As expected based on previous mechanistic studies (28), PF-750 was covalently attached to the S241 nucleophile of h/rFAAH through a carbamate linkage, with the remaining piperidine portion of the parent inhibitor occupying the acyl chain-binding pocket. The aniline leaving group of PF-750 was not observed in the h/rFAAH active site, indicating that this portion of the inhibitor detaches from the enzyme after covalent inactivation. Despite obvious structural differences between PF-750 and MAFP, these inhibitors showed remarkable overlap in their respective binding modes in the h/rFAAH and rFAAH active sites (Fig. S2). Both agents traversed a substantial portion of the FAAH acyl chain-binding pocket, making contacts with side chains on several of the residues that form the surface of this hydrophobic channel. One striking difference, however, was observed at the distal end of the acyl chain-binding pocket, where the presence of the shorter PF-750 group allowed F432 to undergo a conformational shift that moved this residue out of the membrane access channel and into the acyl chain-binding channel (Fig. 4). The net effect of this structural rearrangement is a substantial expansion of the size of the membrane access channel (Fig. 4). Considering that this channel has been postulated to serve as a portal for lipid substrates to enter FAAH from the cell membrane (22), we speculate that F432 may act as a dynamic paddle that directs and orients substrate molecules toward the active site during catalysis.

Fig. 3.

Active site of h/rFAAH in complex with PF-750. (A) The density found at the active site, shown as white 2σ contoured meshes, was modeled as the covalent inhibitor PF-750, shown as purple sticks. The residues surrounding the inhibitor (5-Å radius) are shown in cyan (conserved residues) and violet (humanized residues) sticks. A white diagram representation of the h/rFAAH backbone surrounds the active site. (B) Structural analysis of PF-750 bound to FAAH. The weak H bonds between F192 and F381 and the π-ring of the quinoline moiety are shown as yellow dashed lines. The following moieties are shown in stick representation: rFAAH residues (yellow), PF-750 (purple), h/rFAAH chimera mutated (violet), and conserved (cyan) residues. The rFAAH and h/rFAAH backbones surrounding the active site are shown in yellow and cyan, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Expansion of the membrane access channel of FAAH when bound to PF-750 compared with MAP. (A) Conformational switch of F432 in MAP-rFAAH (Left) vs. PF-750-h/rFAAH (Right) structures. The channels/solvent-filled spaces are shown in dark shadows, and the protein-filled spaces are shown as light areas. MA channel, membrane access channel; AB channel, acyl-binding channel. (B) Opening of MA channel in the PF-750–h/rFAAH structure (Right) compared with the MAP-rFAAH structure (Left). The monomers of each structure have been superposed by using the program Coot.

Multiple key interactions were observed between PF-750 and h/rFAAH that could explain the distinct inhibitor sensitivity profiles of the human and rat enzymes. For instance, aromatic CH–π interactions were observed between the two residues F192 and F381 and the quinoline ring of PF-750 (Fig. 3B). These interactions are at a good distance and geometry (32) and, notably, the F192 interaction is only observed in the human active site. In rFAAH, the corresponding amino acid residue is a leucine, resulting in an increased distance between the residue and bound inhibitor and loss of the hydrophobic interaction. The predicted stabilization energy for an aromatic CH-π interaction is ≈1.0 kcal/mol (32), which would be sufficient to make an important contribution to the overall binding energy and higher potency of PF-750 for hFAAH. An additional interaction with V491 also could contribute to the enhanced potency of PF-750 for hFAAH. This improvement may reflect better steric accommodation of PF-750 by V491 as opposed to the corresponding I491 residue in rFAAH (Fig. 3B). V491 is in good van der Waals distance from PF-750, but replacement of this residue with an isoleucine would be predicted to bring the side chain too close to the quinoline ring of the inhibitor (<3 Å), resulting in steric repulsion (Fig. S2). Interestingly, I491 has also been shown to contribute to fatty acid amide binding in rFAAH (33), suggesting that this residue plays an important role in both substrate and inhibitor recognition.

Discussion

Structural biology has become an integral part of modern drug design programs. Structures can provide atomic resolution insights into small molecule–protein interactions that inform on factors that influence potency and selectivity. A major impediment to the routine implementation of structure-based drug discovery is provided by the challenges that are commonly encountered in expressing human proteins. Integral membrane proteins are particularly troublesome, as evidenced by the dearth of human membrane protein structures in the Protein Data Bank. One alternative is to broaden the scope of structural analysis to include mammalian orthologs of human proteins. If one or more of these ortholog proteins exhibit superior expression and/or stability, they can serve as useful initial surrogates for the human protein of interest. Following this general path, we succeeded in expressing, purifying, and determining the crystal structure of the rat variant of the integral membrane enzyme FAAH (22), which degrades the fatty acid amide class of signaling lipids. Despite providing provocative insights into the general biochemical and catalytic properties of FAAH, this structure offered only limited clues as to the detailed organization of the active site of the human enzyme. Indeed, several residues in the substrate-binding pocket differ between rFAAH and hFAAH, possibly explaining why these enzymes show marked differences in their inhibitor sensitivity profiles.

Here, we have adopted a protein-engineering strategy to address this problem that involves transforming the active site of rFAAH to match that of the human enzyme using site-directed mutagenesis. This interspecies conversion of FAAH active sites provided a protein, termed h/rFAAH, that exhibits the inhibitor sensitivity profile of hFAAH and high-recombinant expression and stable biochemical properties of rFAAH. We exploited this unique combination of features to determine the crystal structure of h/rFAAH in complex with the small molecule inhibitor PF-750.

PF-750 is a prototype member of an emerging class of piperidine/piperazine urea inhibitors of FAAH that display unprecedented selectivity for this enzyme compared with other serine hydrolases (28). The PF-750–h/rFAAH structure confirmed that piperidine/piperazine ureas inhibit FAAH by covalent carbamylation of the catalytic S241 nucleophile of the enzyme. This structure also identified key interactions between PF-750 and residues in the h/rFAAH active site that likely account for the enhanced potency exhibited by this inhibitor for hFAAH over rFAAH. Additional insights gained from the structure offer ideas to improve inhibitor potency for hFAAH further. For instance, substitution of A377 with threonine in the h/rFAAH protein presents a γ-oxygen atom that is located in a suitable position to hydrogen bond with position 6 of the quinoline group of PF-750 (Fig. 3), suggesting that replacement of the latter atom with a hydrogen bond-accepting heteroatom (e.g., nitrogen) could improve potency.

From a broader perspective, we believe that interspecies active-site conversion may serve as a generally useful method for elucidating differences in the properties of enzymes from different species. Despite having been the subject of some discussion and likely activity, especially in the pharmaceutical industry (34), we found surprisingly few examples in the literature where the active sites of enzymes had been converted for the purposes of gaining structural insights into human enzymes and enzyme–inhibitor complexes. Species differences in inhibitor activity are particularly problematic in drug discovery because in vivo efficacy models are largely based on rodent studies, but the candidate inhibitor is ultimately developed as a human drug. A more in-depth understanding of species selectivity is therefore important to produce compounds that are sufficiently active against both rodent and human proteins to progress through the preclinical and clinical phases of drug development. Interspecies active-site conversion combined with the structural biology of enzyme–inhibitor complexes has the potential to impact this process greatly.

Methods

Determination of Kinetic Parameters.

FAAH protein was expressed and purified as described in the SI Methods. GDH-coupled FAAH assays were performed in 96-well UV clear-bottom microplates in a total volume of 200 μl per well at 25°C as described in ref. 28. Briefly, 20 μl of 50% DMSO and 20 μl of oleamide at variable concentrations in 75% ethanol and 25% DMSO were added to a 140-μl reaction mixture containing final concentrations of 48 mM NaPi (pH 7.4), 150 μM NADH, 3 mM α-ketoglutarate, 2 mM ADP, 1 mM EDTA, and 30 units/ml GDH. After the resulting mixture was mixed in a plate vortex, 20 μl of 100 nM (apparent concentration) hFAAH, rFAAH, or h/rFAAH in 20 mM NaPi (pH 7.8) and 1% Triton X-100 was added to initiate the reaction. Absorbance at 340 nm was collected over a period of 90 min with readings taken in 15-s intervals by using a SpectraMax microplate spectrophotometer equipped with Softmax Pro software (Molecular Devices). A background rate determined for samples containing no FAAH was subtracted from all reactions to calculate initial rates (V0). V0 values were plotted against oleamide concentrations ([S]) and fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation, V0 = Vmax[S]/([S] + Km), by using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software) to obtain Km and Vmax values. Turnover numbers (kcat) were calculated by using the equation kcat = Vmax/[E]. Velocities were converted to concentration units according to a standard curve of A340 vs. NADH concentrations obtained under the FAAH assay conditions.

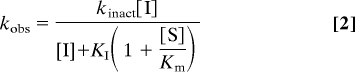

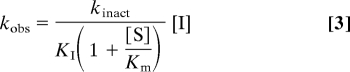

Determination of Potencies (kinact/KI Values) for Irreversible Inhibitors.

The FAAH assay was performed as above except with a final apparent concentration of FAAH of 2–10 nM and in 384-well microplates with a final volume of 50 μl. Inhibitor dilutions and liquid handling for the assay were performed by using Biomek 2000 and Biomek FX (Beckman Coulter), respectively. The reactions were incubated at 30°C, and reaction progress curves (decrease of A340 nm with time) in the presence of various concentrations of inhibitors were collected for 60 min with readings taken in 10-s intervals. Data analysis was performed by using an Excel workbook macro with XLFit software. The macro subtracted background (reactions without enzyme) from each progress curve, fit to a first-order decay equation (Eq. 1) to determine kobserved (kobs) values at each inhibitor concentration, where At is absorbance at time t, A0 is the absorbance at t = infinite, A1 is a total absorbance change (the absorbance difference between t = 0 and t = infinite), and kobs is the first-order rate constant for enzyme inactivation. The inhibitor dissociation constant (KI) and the first-order rate constant of enzyme inactivation at infinite inhibitor concentration (kinact) were then obtained by fitting the kobs vs. [I] curves to Eq. 2. When [I] ≪ KI, Eq. 2 is simplified to Eq. 3, where the kinact/KI is calculated from the slope, kinact/[KI(1 + [S]/Km)], which is obtained from the kobs vs. [I] linear lines.

|

|

Crystallization and Crystal Structure Determination.

A detailed protocol for the crystallization procedure will be published elsewhere. In brief, a 25 mg/ml concentrated protein sample in Hepes (pH 7.0), 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM LiCl, 0.2% n-decyl-β-d-maltoside was supplemented to give final concentrations of 12% xylitol and 2% benzyldimethyldodecylammonium bromide (Sigma). This protein solution was mixed 1:1 with a reservoir buffer containing 100 mM Mes (pH 5.5), 100 mM NaCl, 25% PEG 400. Crystals were grown by sitting-drop vapor diffusion at 14°C in 96-well plates (Innovaplate SD-2; Innovadyne Technologies) and frozen after soaking in mother liquor buffer supplemented with glycerol or PEG 400 as cryo-compatible agent. We collected the crystallographic data at a temperature of 100 K at the GM/CA-CAT beamline of the Advanced Photon Source by using a 5-μm beam collimator (λ:0.97934 Å). Data processing was performed by using XDS softwares and the structure was solved and refined by using programs contained in the CCP4 package. Results from data processing and crystal refinement are provided in Table S1. The crystal was in the P3221 space group with the unit cell containing a FAAH dimer and without twinning, in contrast to the first published structure (22). The cocrystal structure of the h/rFAAH with the covalent inhibitor PF-750 was determined at 2.75 Å resolution by molecular replacement by using the coordinates from a dimer of rFAAH [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1MT5] as a search model. Chemical parameters for PF-750 were calculated by the Dundee PRODRG web server. The good quality of the protein electron density allowed modeling of all of the amino acids, except for part of the N-terminal (amino acids 1–32) and C-terminal ends (amino acids 576–579). Of 915 nonglycine and nonproline residues, 799 are in the Ramachandran most favored regions, and 116 are in the additional allowed regions. Furthermore, 84 molecules of water, 1 chloride ion, and 4 unknown (UNK) atoms were modeled in the (dimeric) structure. The particularly lower B values (37.7 Å2) and higher I/σ values (7.0) compared with the rFAAH structure (PDB code 1MT5) allowed us to build ≈20 residues throughout the structure that were previously missing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank R. Michael Garavito for helpful discussions; James Dunbar and Yuan-Hua Ding for the homology modeling; Yuntao Song, Sue Kesten, Michael Connolly, Lorraine Fay, Michael Walters, and Kuai-Lin Sun for inhibitor synthesis; John Shelly for assisting with purification of hFAAH and h/rFAAH; Donna Paddock for hFAAH expression; and Satya Reddy for FAAH constructs. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DA017259, Pfizer Global Research and Development, and The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2VYA).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0806121105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cravatt BF, et al. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384:83–87. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinney MK, Cravatt BF. Structure and function of fatty acid amide hydrolase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:411–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devane WA, et al. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert DM, Vandevoorde S, Jonsson KO, Fowler CJ. The palmitoylethanolamide family: A new class of antiinflammatory agents? Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:663–674. doi: 10.2174/0929867023370707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cravatt BF, et al. Chemical characterization of a family of brain lipids that induce sleep. Science. 1995;268:1506–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.7770779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez de Fonseca F, et al. An anorexic lipid mediator regulated by feeding. Nature. 2001;414:209–212. doi: 10.1038/35102582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cravatt BF, et al. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9371–9376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kathuria S, et al. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 2003;9:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtman AH, et al. Reversible inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase that promote analgesia: Evidence for an unprecedented combination of potency and selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:441–448. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.069401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lichtman AH, Shelton CC, Advani T, Cravatt BF. Mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase exhibit a cannabinoid receptor-mediated phenotypic hypoalgesia. Pain. 2004;109:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang L, et al. Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase produces analgesia by multiple mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:102–113. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russo R, et al. The fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor URB597 (cyclohexylcarbamic acid 3′-carbamoylbiphenyl-3-yl ester) reduces neuropathic pain after oral administration in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:236–242. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naidu PS, et al. Evaluation of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibition in murine models of emotionality. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreira FA, Kaiser N, Monory K, Lutz B. Reduced anxiety-like behavior induced by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of the endocannabinoid-degrading enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) is mediated by CB1 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gobbi G, et al. Antidepressant-like activity and modulation of brain monoaminergic transmission by blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18620–18625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509591102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huitron-Resendiz S, Sanchez-Alavez M, Wills DN, Cravatt BF, Henriksen SJ. Characterization of the sleep–wake patterns in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Sleep. 2004;27:857–865. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cravatt BF, et al. Functional disassociation of the central and peripheral fatty acid amide signaling systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10821–10826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401292101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massa F, et al. The endogenous cannabinoid system protects against colonic inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1202–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI19465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt S, Comelli F, Costa B, Fowler CJ. Inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase reduce carrageenan-induced hind paw inflammation in pentobarbital-treated mice: Comparison with indomethacin and possible involvement of cannabinoid receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:467–476. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chebrou H, Bigey F, Arnaud A, Galzy P. Study of the amidase signature group. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1298:285–293. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(96)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin S, et al. Structure of malonamidase E2 reveals a novel Ser–cis-Ser–Lys catalytic triad in a new serine hydrolase fold that is prevalent in nature. EMBO J. 2002;21:2509–2516. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bracey MH, Hanson MA, Masuda KR, Stevens RC, Cravatt BF. Structural adaptations in a membrane enzyme that terminates endocannabinoid signaling. Science. 2002;298:1793–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.1076535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boger DL, et al. Trifluoromethyl ketone inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase: A probe of structural and conformational features contributing to inhibition. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:265–270. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00734-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung D, Hardouin C, Boger DL, Cravatt BF. Discovering potent and selective reversible inhibitors of enzymes in complex proteomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:687–691. doi: 10.1038/nbt826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deutsch DG, et al. Methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate: A potent irreversible inhibitor of anandamide amidase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00830-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boger DL, et al. Exceptionally potent inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase: The enzyme responsible for degradation of endogenous oleamide and anandamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5044–5049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander JP, Cravatt BF. Mechanism of carbamate inactivation of FAAH: Implications for the design of covalent inhibitors and in vivo functional probes for enzymes. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1179–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn K, et al. Novel mechanistic class of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitors with remarkable selectivity. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13019–13030. doi: 10.1021/bi701378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patricelli MP, Lashuel HA, Giang DK, Kelly JW, Cravatt BF. Comparative characterization of a wild-type and transmembrane domain-deleted fatty acid amide hydrolase: Identification of the transmembrane domain as a site for oligomerization. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15177–15187. doi: 10.1021/bi981733n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kage KL, et al. A high-throughput fluorescent assay for measuring the activity of fatty acid amide hydrolase. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;161:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang H, Nishi K, Tsai HJ, Hammock BD. Development of highly sensitive fluorescent assays for fatty acid amide hydrolase. Anal Biochem. 2007;363:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brandl M, Weiss MS, Jabs A, Suhnel J, Hilgenfeld R. C-H–pi interactions in proteins. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:357–377. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Characterization and manipulation of the acyl chain selectivity of fatty acid amide hydrolase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6107–6115. doi: 10.1021/bi002578r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Appelt K, et al. Design of enzyme inhibitors using iterative protein crystallographic analysis. J Med Chem. 1991;34:1925–1934. doi: 10.1021/jm00111a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.