Abstract

Deregulation of the PI3K signaling pathway is observed in many human cancers and occurs most frequently through loss of PTEN phosphatase tumor suppressor function or through somatic activating mutations in the Class IA PI3K, PIK3CA. Tumors harboring activated p110α, the protein product of PIK3CA, require p110α activity for growth and survival and hence are expected to be responsive to inhibitors of its lipid kinase activity. Whether PTEN-deficient cancers similarly depend on p110α activity to sustain activation of the PI3K pathway has been unclear. In this study, we used a single-vector lentiviral inducible shRNA system to selectively inactivate the three Class IA PI3Ks, PIK3CA, PIK3CB, and PIK3CD, to determine which PI3K isoforms are responsible for driving the abnormal proliferation of PTEN-deficient cancers. Down-regulation of PIK3CA in colorectal cancer cells harboring mutations in PIK3CA inhibited downstream PI3K signaling and cell growth. Surprisingly, PIK3CA depletion affected neither PI3K signaling nor cell growth in 3 PTEN-deficient cancer cell lines. In contrast, down-regulation of the PIK3CB isoform, which encodes p110β, resulted in pathway inactivation and subsequent inhibition of growth in both cell-based and in vivo settings. This essential function of PIK3CB in PTEN-deficient cancer cells required its lipid kinase activity. Our findings demonstrate that although p110α activation is required to sustain the proliferation of established PIK3CA-mutant tumors, PTEN-deficient tumors are dependent instead on p110β signaling. This unexpected finding demonstrates the need to tailor therapeutic approaches to the genetic basis of PI3K pathway activation to achieve optimal treatment response.

The PI3K signaling pathway is a critical regulator of many cellular processes that promote the transformation of a normal cell to a cancer cell. Initiation of this signaling cascade commences with the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to produce phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), which results in cell proliferation, motility, and survival, among many other cellular changes (1). Cellular phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate levels are regulated tightly by the opposing activities of the lipid phosphatase PTEN and the lipid kinase activity of Class IA PI3Ks (2). PTEN inactivation disrupts this balanced reaction and leads to deregulated cell growth (3–5). Consequently, the finding that PTEN frequently is inactivated in many tumors provided the first direct evidence linking the PI3K pathway to the etiology of human cancers (6–8). In addition, recent sequencing analyses revealed that one of the Class IA PI3K isoforms, PIK3CA, frequently is activated through somatic mutations in many cancers (9–14). The observation that PTEN loss and PIK3CA somatic activating mutations occur in most human tumors in a mutually exclusive fashion strongly indicates that hyperactivation of the PI3K pathway is an essential driver of tumorigenesis (15–19).

Growing evidence supporting the dependency of cancer cells on deregulated PI3K pathway activity for survival has resulted in considerable efforts directed at developing pharmacological inhibitors to stem aberrant PI3K signaling in tumors (20). So far, the challenges of restoring the activity of loss-of-function mutations characteristic of tumor suppressors have precluded PTEN as a viable target for drug discovery. On the other hand, recent successes in developing small-molecule inhibitors against activated kinases have spurred considerable interest in PI3Ks as targets for anticancer drugs (21, 22). Of particular interest are the Class IA PI3Ks, which encompass the three p110 lipid kinase subunits, p110α, p110β, and p110δ, because they are primarily responsible for phosphorylating the critical signaling molecule, PIP2 (23). First-generation pan-PI3K inhibitors target all 3 Class IA isoforms (24, 25). Even though Class IA isoforms share many structural and regulatory similarities, the increasing biological understanding of these lipid kinases indicates that they have nonredundant cellular functions (26–29). Thus, concerns about unnecessary isoform-derived on-target toxicities of pan-PI3K inhibitors have directed considerable efforts toward the development of isoform-selective inhibitors (30).

Although it generally is accepted that somatic activating mutations in PIK3CA are important for tumorigenesis, it has not yet been demonstrated formally that aberrant p110α activity is required to maintain the transformed phenotype in established tumors. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether p110α activity, either alone or in combination with other Class IA lipid kinases, drives cell growth and survival in PTEN-deficient cancers. To clarify the role of p110α in the maintenance of PIK3CA-mutant cells and to identify the Class IA lipid kinase required to drive PI3K pathway signaling in PTEN-deficient tumors, we have generated a single-vector inducible shRNA system to inactivate individual Class IA PI3Ks isoforms potently and selectively in a panel of cancer cell lines. PIK3CA depletion in 2 colorectal cancer cell lines, HCT116 and DLD1, each harboring a unique hotspot mutation in PIK3CA, resulted in reduced proliferation, colony formation, and soft agar growth and strongly inhibited downstream pathway signaling. Importantly, RNAi–mediated depletion of PIK3CA in HCT116 tumor xenografts resulted in tumor growth retardation, providing direct evidence that inactivation of PIK3CA in an established tumor setting leads to inhibition of tumor growth. In contrast, we surprisingly found that depletion of PIK3CA does not affect signaling through the PI3K pathway in the PTEN-deficient cancer cell lines PC3, BT549, and U87MG, nor does it impact their transformed phenotypes. Instead, down-regulation of PIK3CB resulted in strong inhibition of growth and PI3K pathway signaling in all PTEN-deficient cell lines tested. We further demonstrate that the lipid kinase activity of p110β is required to sustain PI3K signaling in PTEN-deficient cancer cells, providing a strong rationale for the development of p110β-specific inhibitors for the treatment of PTEN-deficient cancers.

Results

PIK3CA Depletion Results in Suppression of Downstream PI3K Signaling and Leads to Growth Inhibition of Colon Cancer Cell Lines with PIK3CA Mutations.

To assess accurately the dependency of tumors on PIK3CA for both initiation and maintenance of the tumorigenic phenotype, we developed a single-vector lentiviral doxycycline-inducible shRNA system that allows efficient and regulatable target gene knockdown in multiple cell lines [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. Two human colorectal cancer cell lines, HCT116 and DLD1, were stably transduced with the inducible vector containing either scrambled control sequence or shRNA targeting PIK3CA. In the absence of doxycycline, the levels of PIK3CA mRNA and protein product were similar in both the control shRNA-expressing cells and the PIK3CA shRNA-expressing cells. In sharp contrast, the addition of doxycycline resulted in a dramatic down-regulation of PIK3CA mRNA (> 90% knockdown) (Fig. 1A) and concurrent reduction in p110α protein levels (Fig. 1B) only in the cells expressing PIK3CA shRNA. No measurable off-target effects on other Class IA PI3K isoforms were observed as determined by quantitative RT-PCR (data not shown).

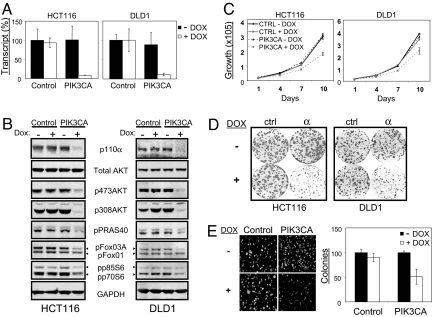

Fig. 1.

PIK3CA is required for PI3K signaling and growth in p110α-mutant cell lines. Dox = doxycycline. (A) HCT116 and DLD1 colorectal cancer cell lines transduced with scramble control or PIK3CA-inducible shRNA were cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline at 10 ng/ml for 72 h and harvested for Taqman analysis. PIK3CA mRNA levels in the control samples (− DOX) were set to 100%. (B) Similarly treated cells were analyzed by Western blot to monitor changes in PI3K pathway signaling. The phosphorylation states of PRAS40 at Thr-246, Foxo1 at Thr-24, Foxo3a at Thr-32, and p70/p85 S6K at Thr 389 were assessed. Endogenous GAPDH is shown as a loading control. (C) Proliferation of stable HCT116 and DLD1 shRNA cell lines under low (0.5% FBS) serum conditions in the presence or absence of doxycycline (10 ng/ml) were monitored using CellTiterGlo over a 10-day period. Results are shown as mean ± SE of 3 replicates. (D) Cells cultured in a 6-well dish for 14 days in the presence (10 ng/ml) or absence of doxycyline were stained with crystal violet to visualize colony growth. All experiments were done in triplicates. (E) HCT116 cells were grown in semisolid medium for 14 days in the presence (100 ng/ml) or absence of doxycycline. Colonies were visualized by Hoechst 33342 staining and photographed using a Nikon fluorescence microscope. Colonies were counted (mean ± SE, in triplicate) using ImagePro software.

We next determined the contribution of PIK3CA to the tumorigenic phenotype in the colorectal cancer cell lines HCT116 and DLD1. HCT116 has an H1047R mutation in exon 20 (kinase domain), whereas DLD1 contains an E545K alteration in exon 9 (helical domain) (31). Because it is well accepted that the p110α mitogenic signal is propagated through a number of well-characterized downstream targets, we hypothesized that inducible knockdown of PIK3CA would alter the phosphorylation state of key p110α effector proteins. Indeed, down-regulation of PIK3CA was accompanied by substantial reduction in phospho-AKT, phospho-FOXO, phospho-PRAS40, and phospho-S6 in both cell lines (Fig. 1B). To assess phenotypic consequences of PIK3CA knockdown, we studied the proliferation of stable shRNA cell lines in the absence or presence of doxycycline under full (10%) (data not shown) or reduced (0.5%) serum conditions over a 10-day period. Proliferation of cells containing shRNA targeting PIK3CA in the absence of doxycycline was indistinguishable from the control shRNA-expressing cells. Depletion of PIK3CA in both HCT116 and DLD1 lines significantly decreased growth under all conditions studied (Fig. 1C). PIK3CA knockdown also strongly impaired the ability of colorectal cancer cells to survive and grow when plated at low density (Fig. 1D). Finally, anchorage-independent growth of HCT116 cells, a hallmark of the transformed phenotype, also was suppressed by PIK3CA depletion (Fig. 1E). Consistent with previously published results, silencing of PIK3CA in HCT116 cells resulted in poly(ADP ribose) polymerase cleavage, suggestive of increased levels of apoptosis, and prolonged G1 phase of the cell cycle as determined by FACS analysis (data not shown). These data are consistent with earlier findings that colorectal cancer cell lines containing mutations in PIK3CA are dependent on p110α for proliferation and survival (31).

Down-Regulation of PIK3CA in PTEN-Deficient Cancer Cell Lines Affects Neither Signaling Through the PI3K Pathway nor Cell Growth and Survival.

Most cancers with deregulated PI3K signaling have acquired either an activating mutation in PIK3CA or an inactivating mutation in the opposing lipid phosphatase PTEN. To investigate whether the increase in signaling through the PI3K pathway in PTEN-deficient cell lines depends on p110α lipid kinase activity, we introduced the inducible shRNA targeting PIK3CA into PC3, U87MG, and BT549, which were confirmed to be PTEN deficient (Fig. S2A). These cancer cell lines represent the major cancer types with a high frequency of PTEN inactivation, namely prostate cancer (30%–50%) (32), brain cancer (>30%) (33), and breast cancer (20%) (34). Greater than 90% knockdown of PIK3CA mRNA was achieved in PC3 and BT549 cell lines, whereas ≈80% knockdown was observed in U87MG upon shRNA induction (Fig. 2A). Correspondingly, a strong reduction in p110α protein levels was observed by Western analysis in all 3 lines (Fig. 2B). In contrast to HCT116 and DLD1 cells, however, the levels of the major downstream PI3K pathway effector, phospho-AKT, were not affected by PIK3CA depletion in all PTEN-deficient cell lines tested (Fig. 2B). The differential response to PIK3CA silencing could not be explained by gross differences in PIK3CA expression levels (Fig. S2B) or PIK3CA-knockdown efficiencies (Fig. S2C).

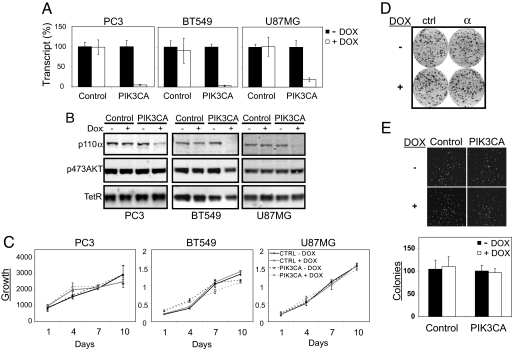

Fig. 2.

PIK3CA activity is not required for PI3K signaling or growth in PTEN-deficient cancer cell lines. DOX = doxycycline. (A) BT549, PC3, and U87MG cell lines transduced with scramble control or PIK3CA inducible shRNA were cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline (10 ng/ml) for 72 h and harvested for Taqman analysis. PIK3CA mRNA levels in the control samples (− DOX) were set to 100%. (B) Similarly treated cells were analyzed by Western blot to monitor changes in p110α levels upon PIK3CA knockdown and the effect on p473AKT signaling. Constitutively expressed TetR protein was used as a loading control. (C) Proliferation of PC3 cells was monitored over 10 days using CellTiterGlo. BT549 and U87MG cell proliferation was monitored by MTS assay over 10 days. (D) shRNA stable cell lines were seeded in triplicates onto 6-well dishes (1500 cells per well) and allowed to attach for 24 h. Doxycycline was added to the indicated wells at a final concentration of 10 ng/ml. Following 10-day incubation, dishes were fixed and stained with crystal violet. (E) Control or PIK3CA shRNA PC3 cells were grown in semisolid medium for 14 days in the presence or absence of doxycycline (100 ng/ml). The resulting colonies were visualized by Hoechst 33342 staining and photographed using a Nikon fluorescence microscope. Colonies were counted using ImagePro software (mean ± SE, in triplicate).

Consistent with the unperturbed PI3K downstream signaling, depletion of PIK3CA in PTEN-deficient cell lines also did not affect cell proliferation (Fig. 2C). Because of the high frequency of PTEN deletions found in prostate cancer, we focused on PC3 cell line to further examine the role of PIK3CA depletion in PTEN-deficient cells. In a clonogenic survival assay, the down-regulation of PIK3CA in PC3 stable cells did not affect colony size or number in comparison to the doxycycline-untreated cells (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, PIK3CA down-regulation did not affect the soft agar growth of PC3 cells (Fig. 2E).

PIK3CA Depletion Inhibits Phospho-AKT and Tumor Growth in HCT116 but not in PC3 Xenografts.

To address the dependency of both PIK3CA-mutant and PTEN-deficient cells on PIK3CA in an in vivo setting, we next assessed the effect of inducible silencing of PIK3CA in tumor xenograft models. Although somatic cell knockout experiments demonstrated that PIK3CA is important for the proliferation of PIK3CA-mutant tumors (31), these experiments could not distinguish between its role in tumor initiation versus maintenance. Using our inducible knockdown system, we therefore sought to determine if p110α activity also is required for the maintenance of established tumors. HCT116 cells stably expressing inducible shRNA targeting PIK3CA were implanted into nude mice and allowed to establish as tumor xenografts. Once tumor volume exceeded 100 mm3, doxycycline or vehicle was administered to tumor-bearing animals either continuously in drinking water or once a day via oral gavage. Doxycycline treatment resulted in significant inhibition of HCT116-PIK3CA shRNA tumor growth (the mean increase of tumor volumes of treated animals divided by the mean increase of tumor volumes of control animals multiplied by 100 [T/C] < 50%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A) but had no effect on the growth of wild-type HCT116 xenografts or mouse body weight regardless of the administration route (data not shown). To confirm the knockdown of endogenous p110α levels and to assess its effect on downstream PI3K signaling, tumor xenografts samples were analyzed at the end of the study. PIK3CA protein levels were reduced dramatically in doxycycline-treated tumors compared with their vehicle-treated counterparts (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, PIK3CA down-regulation was accompanied by the suppression of phospho-AKT, its direct downstream substrate phospho-PRAS40, and its indirect target phospho-S6 (Fig. 3C).

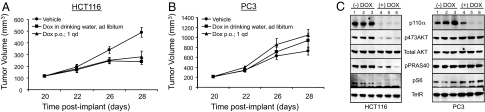

Fig. 3.

PIK3CA is required for growth of p110α mutant, but not PTEN-deficient, tumors in vivo. Dox = doxycycline. (A and B) HCT116 and PC3 cells stably transduced with PIK3CA inducible shRNA were implanted into nude mice as described in Materials and Methods. Mice containing tumors of at least 100 mm3 were administered vehicle control or doxycycline either freely in drinking water (ad libitum) or once a day (qd) by oral gavage (p.o.). Tumor volume was monitored by calipering (mean ± SEM). (C) Changes in PI3K signaling in tumor xenografts were assessed by Western blot using indicated antibodies. Phosphorylation states of PRAS40 at Thr 246 and S6 at Ser-235/S236 were assessed.

In striking contrast, shRNA-mediated inhibition of PIK3CA did not affect the growth of PC3 PTEN-deficient tumor xenografts (Fig. 3B), despite significant down-regulation of p110α levels (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the results from cell-based assays, knockdown of PIK3CA did not alter downstream PI3K pathway effectors in PC3 xenografts (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that tumors harboring activating somatic mutations in PIK3CA depend on p110α for maintenance of both signaling through the PI3K pathway and growth, whereas PTEN-deficient tumors are p110α independent.

p110α Is Dispensable for the Maintenance of PI3K Signaling in the Absence of PTEN.

To confirm further that p110α is dispensable to the maintenance of PI3K signaling in the absence of PTEN, we tested if inactivation of PTEN would render PIK3CA-mutated cells p110α independent. HCT116 cells stably expressing inducible shRNA targeting PIK3CA were transfected transiently with either control or PTEN siRNA and were incubated in the absence or presence of doxycycline. Interestingly, we observed that, even in the presence of an activating PIK3CA mutation, loss of PTEN alone was able to further increase signaling through the PI3K pathway (Fig. 4A; compare lanes 3, 4, and 7 with lanes 1, 2, and 5). More importantly, although knockdown of PIK3CA alone resulted in a dramatic reduction of phospho-AKT levels (Fig. 4A; compare lane 6 with lanes 1, 2, and 5), the double knockdown of both PTEN and PIK3CA fully restored the phosphorylation of AKT (Fig. 4A; compare lane 8 with lanes 1, 2, and 5). This finding further demonstrates that the activation of the PI3K pathway resulting from PTEN loss does not depend on p110α activity.

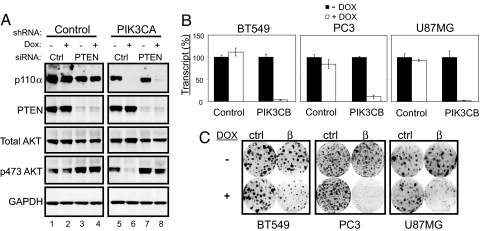

Fig. 4.

PTEN-deficient cells require PIK3CB for growth. Dox = doxycycline. (A) Stable control or PIK3CA shRNA–containing HCT116 cells were transfected with either control or PTEN siRNA. Cells grown in the absence or presence of doxycycline were harvested for Western blot analysis after 72 h of treatment. (B) BT549, PC3, and U87MG cells stably transduced with either scramble control or PIK3CB were grown in the presence or absence of doxycycline for 72 h. PIK3CB transcript levels were assessed at the end of treatment by Taqman RT-PCR. (C) Described cells were cultured in a 6-well dish in the presence or absence of doxycycline (10 ng/ml) for 14 days. The effects of PIK3CB silencing on foci formation were visualized by crystal violet staining.

PTEN-Deficient Cells Depend on PIK3CB for Signaling and Cell Growth.

The finding that phospho-AKT levels are not perturbed after PIK3CA depletion in the genetic context of PTEN deficiency suggested that PI3K signaling may be mediated by other PI3K isoforms. We therefore introduced inducible shRNAs targeting the 2 remaining Class IA PI3Ks, PIK3CB and PIK3CD, into the 3 PTEN-deficient cell lines BT549, PC3, and U87MG. Whereas knockdown of PIK3CD did not affect signaling in any of the 3 PTEN-deficient lines tested (data not shown), depletion of PIK3CB (Fig. 4B) resulted in striking inhibition of growth in these cell lines (Fig. 4C). Importantly, an independent shRNA targeting a different region of the PIK3CB transcript similarly inhibited growth of PC3 cells in a clonogenic survival assay (Fig. S3).

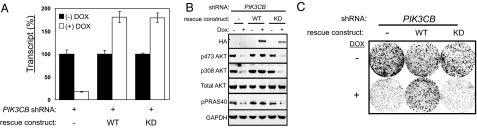

To directly test whether the lipid kinase activity of p110β is required for the survival of PTEN-deficient cancer cells, we used an shRNA-rescue strategy. Wild-type PIK3CB cDNA was modified to contain 6 synonymous mutations in the shRNA targeting region and expressed using a doxycycline-regulated lentiviral vector system (Fig. S1). In addition, an shRNA-resistant lipid kinase–dead mutant, p110βD937A, was generated by converting the ATP-binding DFG motif to AFG. The expression levels of both shRNA-resistant p110β rescue constructs were similar to the endogenous level (Fig. 5A) and did not affect the growth or signaling in PC3 cells expressing control shRNA (Fig. S4A–C). Re-expression of wild-type p110β, but not its kinase-dead counterpart, restored both PI3K pathway signaling and cell growth (Fig. 5 B and C) in PC3 cells depleted for endogenous PIK3CB. These data indicate that PTEN-deficient cells specifically require p110β lipid kinase activity to sustain PI3K pathway signaling and abnormal cell proliferation.

Fig. 5.

p110β-Lipid kinase activity is required for PI3K pathway signaling and growth in PTEN-deficient cells. Stable PC3 cells containing inducible PIK3CB targeting shRNA were transduced with either wild-type or kinase-dead (D937A) shRNA-resistant p110β cDNA. Dox = doxycycline. (A) PIK3CB transcript levels were assessed by Taqman analysis in the absence or presence of 10 ng/ml of doxycycline treatment for 72 h. (B) The effect on PI3K pathway signaling was assessed by Western blot analysis upon expression of the respective rescue construct for 96 h. The effect on PRAS40 phosphorylation at Thr 246 was determined. (C) Stable PC3 cells containing the respective rescue constructs were cultured in a 6-well dish for 14 days in the presence (10 ng/ml) or absence of doxycycline. Cells were stained with crystal violet to visualize colony growth. All experiments were done in triplicate.

p110β-Specific Compounds Inhibit Signaling and Cell Growth in PTEN-Deficient Cells but not in PIK3CA-Mutant Cells.

The recent development of isoform-selective compounds allowed us to test whether small-molecular-weight inhibitors can recapitulate our genetic findings, which predict that PTEN-deficient and p110α-mutant cells would exhibit different sensitivities to isoform-specific Class IA PI3K inhibitors. As expected, treatment of all cell lines with the pan-PI3K inhibitor, BEZ235 (24), reduced phospho-AKT levels (Fig. S5A). Strikingly, the p110β-selective inhibitor TGX221 (26) inhibited phospho-AKT levels only in PTEN-deficient cells (Fig. S5A), fully consistent with our results using the isoform-selective inducible shRNAs. Similar results were obtained in a recent study using the same p110β compound in a panel of breast cancer cell lines (35). The p110δ-specific inhibitor IC87114 (36), however, did not impact phospho-AKT levels in any of the lines tested (Fig. S5A). Furthermore, the combined inactivation of p110δ and p110α in PC3 cells did not inhibit phospho-AKT levels (data not shown).

We next addressed whether p110β selective-inhibitor treatment would result in cell growth inhibition in PTEN-deficient cells. Both TGX221 and a second p110β-selective inhibitor, TGX256, led to sustained inactivation of PI3K pathway signaling (Fig. S5C) and inhibited foci formation in PC3 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S5B). Collectively, these findings further demonstrate that p110β is both necessary and sufficient to sustain PI3K pathway signaling and proliferation in PTEN-deficient cancer cells.

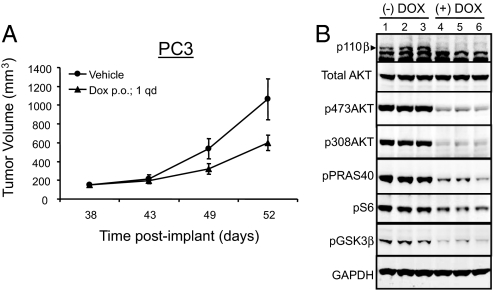

Inactivation of PIK3CB Inhibits Growth and PI3K Pathway Signaling in a PTEN-Deficient Tumor Xenograft Model.

To determine the functional consequences of PIK3CB inactivation in a tumor setting, PC3 cells containing the inducible shRNA targeting PIK3CB were implanted into nude mice. As described earlier, tumors were allowed to reach at least 100 mm3 before administration of either doxycycline or vehicle control by oral gavage. Tumor volume was measured over the 14 days of doxycycline treatment. Consistent with our cell-based studies, inactivation of PIK3CB resulted in significant tumor growth inhibition (T/C = 49%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A). To confirm successful target gene knockdown, representative tumor samples harvested from mice at the end of the study were analyzed by Western blot. Both the targeted protein, p110β, and its downstream effectors, phospho-AKT, phospho-PRAS40, phospho-S6, and phospho-GSK3β, were suppressed in doxycycline-treated but not in vehicle-treated tumor xenografts (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these findings strongly indicate that p110β is the critical PI3K isoform driving PI3K pathway activation and abnormal proliferation in PTEN-deficient tumors.

Fig. 6.

PIK3CB is required for growth of PTEN-deficient tumors in vivo. Dox = doxycycline. (A) Stable PC3 cells containing PIK3CB inducible shRNA were implanted into nude mice and administered vehicle control or doxycycline by oral gavage (p.o.) once per day (qd) upon tumors reaching 100 mm3. Tumor volume was measured using calipers (mean ± SEM). (B) Tumors harvested from either untreated or doxycycline-treated mice were analyzed by Western blot with the respective antibodies. The phosphorylation states of PRAS40 at Thr 246, of S6 at Ser-235/S236, and of GSK3β at Ser-9 were determined.

Discussion

The PI3K signaling pathway is one of the most frequently activated pathways in cancers (37). PIK3CA gain-of-function or PTEN loss-of-function mutations are the most frequent genetic alterations in this pathway. In this study we set out to determine which PI3K isoforms are most critical for growth and pathway signaling in cancer cells containing these different genetic lesions. Consistent with the analysis of somatic PIK3CA knockout cell lines (31), we found that depletion of PIK3CA using an inducible shRNA leads to a marked decrease in the phosphorylation of key p110α downstream targets and inhibits proliferation of the PIK3CA mutant colorectal cancer cell lines HCT116 and DLD1. In addition, PIK3CA knockdown also led to a dramatic reduction in downstream PI3K signaling and tumor growth inhibition in an in vivo PIK3CA mutant xenograft model. The inducible nature of our shRNA system allowed us to expand on previous work by demonstrating that PI3K signaling is important not only for the initiation but also for the maintenance of established colorectal tumor xenografts. Together, our in vivo results further validate p110α as a promising therapeutic target in PIK3CA mutant cancers.

The clinical observation that PIK3CA and PTEN mutations occur in almost all cancers in a mutually exclusive fashion (15–18), combined with the absence of somatic cancer mutations in PIK3CB or PIK3CD, provided strong genetic indication that the tumorigenic effects of PTEN loss may be mediated by p110α. Our study, however, revealed that knockdown of PIK3CA in PTEN-deficient cancer cell lines neither alters PI3K signaling nor has an effect on cell growth and survival. Based on these findings, we would predict that many PTEN-deficient cancers will not respond to a selective p110α inhibitor.

Our data clearly demonstrate that p110β is the critical lipid kinase that drives PI3K pathway activation, cell growth, and survival in PTEN-deficient cancer cell lines. This unexpected finding raises many important questions regarding the function of p110 isoforms in both normal and cancer cells. For instance, given the importance of p110β in PTEN-deficient cells, it is surprising that p110β, in stark contrast to p110α, does not seem to be mutated in human cancers (9). One possible explanation may be that p110β has significant activity in the absence of growth factor stimulation. Thus, in the absence of the PTEN lipid phosphatase activity, the unabated phosphorylation of PIP2 by p110β would result in aberrant activation of PI3K downstream effector pathways. In contrast, p110α lipid kinase activation may have very low basal activity and can be activated only upon growth factor stimulation. In this model, mutational activation of the normally inactive p110α would provide greater selective growth advantage to cancer cells than the incremental activation of an already active p110β. In addition, differences in the activity of regulatory subunits to control individual p110-isoform activities may further limit any selective advantages gained from mutating p110β (38–40).

Although the dependency on p110β for both PI3K pathway signaling and growth in the panel of PTEN-deficient cell lines assessed in this study is very striking, it is conceivable that the requirement for p110β in PTEN-deficient cells is highly dependent on its genetic context. For example, in rare instances where PTEN loss-of-function mutations coexist with PIK3CA-activating mutations (19), as is the case in the ovarian cancer cell line A2780, down-regulation of p110α activity, but not of p110β activity, resulted in PI3K pathway inactivation and cell growth inhibition (Fig. S6 A–D). We favor the hypothesis that the 9-nucleotide deletion spanning the PTEN lipid phosphatase domain observed in A2780 cells generates a hypomorphic rather than null PTEN protein. Thus, the partially active PTEN protein allows additional selective advantage for the acquisition of PIK3CA mutations. In this setting, PIK3CA-activating mutations may be dominant to inactivating mutations in PTEN. Therefore, we speculate that p110β dependency may be most penetrant in cancers cells harboring PTEN-null alleles in the absence of PIK3CA mutations. This hypothesis remains to be tested in larger cancer cell panels. Taken together, these findings indicate that the genetic context in which inactivating mutations in PTEN are found is likely to dictate its dependency on individual Class IA PI3Ks.

In conclusion, our results have significant implications for the ongoing and future efforts to discover drugs targeting the PI3K pathway. Pan-Class IA PI3K inhibitors are expected to have the broadest clinical utility, because they are expected to retard growth of both PIK3CA mutant and PTEN-null cancers. However, the important functions of individual PI3K isoforms in normal tissue homeostasis raise concerns about dose-limiting on-target side effects (30). Isoform-selective drugs that target only the relevant oncogenic PI3K isoform hold great promise for circumventing unnecessary isoform-derived toxicities and thereby should provide a larger therapeutic window. In this light, our study provides a strong rationale for the development of p110β-specific inhibitors for the treatment of PTEN-deficient cancers. More generally, our findings further highlight the need to match thoughtfully the molecular and genetic signature of a particular cancer with the appropriate anti-PI3K therapy.

Materials and Methods

A detailed description of the Materials and Methods can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Drs. William Sellers, Marion Dorsch, Christine Fritsch, Steve Fawell, Carlos Garcia-Echeverria (Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research), and Thomas Roberts (Dana Farber Cancer Institutes) for fruitful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Note.

While this manuscript was under review, Jia, et al. (41) reported that p110b is essential to the transformed phenotype in a PTEN-null prostate cancer mouse model.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: All authors are employees of the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0802655105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salmena L, Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell. 2008;133:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M-L, et al. The deficiency of Akt1 is sufficient to suppress tumor development in Pten+/− mice10.1101/gad. 1395006. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1569–1574. doi: 10.1101/gad.1395006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Choi Y, Mavromatis B, Lichtenstein A, Li W. Preferential killing of PTEN-null myelomas by PI3K inhibitors through Akt pathway. Oncogene. 2003;22:6289–6295. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayascas JR, Leslie NR, Parsons R, Fleming S, Alessi DR. Hypomorphic mutation of PDK1 suppresses tumorigenesis in PTEN+/− mice. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1839–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steck PA, et al. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat Genet. 1997;15:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuels Y, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell IG, et al. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7678–7681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachman KE, et al. The PIK3CA gene is mutated with high frequency in human breast cancers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:772–775. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.8.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JW, et al. PIK3CA gene is frequently mutated in breast carcinomas and hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncogene. 2005;24:1477–1480. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine DA, et al. Frequent mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2875–2878. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu G, et al. Somatic mutation and gain of copy number of PIK3CA in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R609–R616. doi: 10.1186/bcr1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsons DW, et al. Colorectal cancer: Mutations in a signalling pathway. Nature. 2005;436:792. doi: 10.1038/436792a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saal LH, et al. PIK3CA mutations correlate with hormone receptors, node metastasis, and ERBB2, and are mutually exclusive with PTEN loss in human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2554–2559. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472-CAN-04-3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abubaker J, et al. PIK3CA mutations are mutually exclusive with PTEN loss in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2007;21:2368–2370. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, et al. High prevalence and mutual exclusivity of genetic alterations in the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/akt pathway in thyroid tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2387–2390. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oda K, Stokoe D, Taketani Y, McCormick F. High frequency of coexistent mutations of PIK3CA and PTEN genes in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10669–10673. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maira SM, Voliva C, Garcia-Echeverria C. Class IA phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase: From their biologic implication in human cancers to drug discovery. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:223–238. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen P. Protein kinases—the major drug targets of the twenty-first century? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nrd773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao JJ, Roberts TM. PI3 kinases in cancer: From oncogene artifact to leading cancer target. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:pe52. doi: 10.1126/stke.3652006pe52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wymann MP, Pirola L. Structure and function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1436:127–150. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stauffer F, Maira SM, Furet P, Garcia-Echeverria C. Imidazo[4,5-c]quinolines as inhibitors of the PI3K/PKB-pathway. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1027–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raynaud FI, et al. Pharmacologic characterization of a potent inhibitor of class I phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5840–5850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okkenhaug K, et al. Impaired B and T cell antigen receptor signaling in p110delta PI 3-kinase mutant mice. Science. 2002;297:1031–1034. doi: 10.1126/science.1073560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foukas LC, et al. Critical role for the p110alpha phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase in growth and metabolic regulation. Nature. 2006;441:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature04694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson SP, et al. PI 3-kinase p110beta: a new target for antithrombotic therapy. Nat Med. 2005;11:507–514. doi: 10.1038/nm1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMullen JR, et al. Protective effects of exercise and phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110{alpha}) signaling in dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PNAS. 2007;104:612–617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606663104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wee S, Lengauer C, Wiederschain D. Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase isoforms and human tumorigenesis: Implications for cancer drug discovery and development. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:77–82. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282f3111e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samuels Y, et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:561–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cairns P, et al. Frequent inactivation of PTEN/MMAC1 in primary prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4997–5000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiariello E, Roz L, Albarosa R, Magnani I, Finocchiaro G. PTEN/MMAC1 mutations in primary glioblastomas and short-term cultures of malignant gliomas. Oncogene. 1998;16:541–545. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feilotter HE, et al. Analysis of the 10q23 chromosomal region and the PTEN gene in human sporadic breast carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:718–723. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torbett NE, et al. A chemical screen in diverse breast cancer cell lines reveals genetic enhancers and suppressors of sensitivity to PI3K isotype-selective inhibition. Biochem J. 2008 doi: 10.1042/BJ20080639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadhu C, Dick K, Tino WT, Staunton DE. Selective role of PI3K delta in neutrophil inflammatory responses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308:764–769. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01480-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brugge J, Hung MC, Mills GB. A new mutational AKTivation in the PI3K pathway. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beeton CA, Chance EM, Foukas LC, Shepherd PR. Comparison of the kinetic properties of the lipid- and protein-kinase activities of the p110alpha and p110beta catalytic subunits of class-Ia phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 2):353–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kubo H, Hazeki K, Takasuga S, Hazeki O. Specific role for p85/p110beta in GTP-binding-protein-mediated activation of Akt. Biochem J. 2005;392:607–614. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurosu H, et al. Heterodimeric phosphoinositide 3-kinase consisting of p85 and p110beta is synergistically activated by the betagamma subunits of G proteins and phosphotyrosyl peptide. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24252–24256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia S, et al. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110beta in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.