The enzyme paraoxonase 1 (PON1) is an excellent example of a multitasking protein, displaying at least two very important functions: hydrolysis of organophosphorus (OP) anticholinesterases and prevention of oxidation of low density lipoproteins (LDLs) and high density lipoproteins (HDLs). PON1 is associated with the HDL particle and is a member of a family of calcium-dependent hydrolases (1). Interest in PON1 has escalated in recent years because of its two highly important roles, the first related to protection from OP compound poisoning from nerve agents (chemical warfare agents also used in terrorist attacks) and from agricultural insecticides, and the second related to protection against cardiovascular disease. The current study from the Furlong laboratory in this issue of PNAS (2) demonstrates the feasibility of producing in Escherichia coli recombinant human PON1 engineered to be more efficient catalytically toward several substrates than are the native human forms of PON1. This greater enzymatic efficiency offers promise of a potential catalytic therapeutic agent more effective than current therapies at saving lives and preserving health.

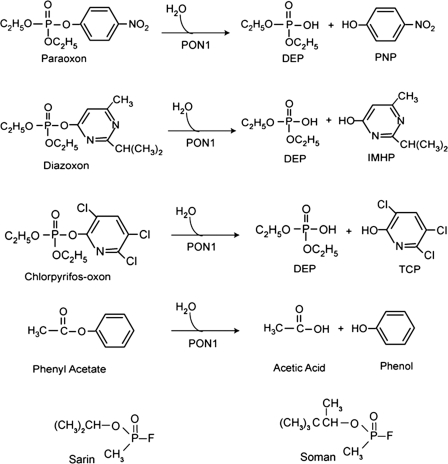

Historically, OP compound hydrolysis was the first function ascribed to PON, with the hydrolysis of the OP compound paraoxon providing PON1 with its name, paraoxonase. Paraoxon is the active anticholinesterase metabolite of parathion, one of the earliest compounds in the highly successful class of OP insecticides, developed and characterized as an insecticide in the 1940s and 1950s. The OP insecticides developed out of the same chemical technology that produced the OP nerve agents, and both the insecticides and the nerve agents act through the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and can lead to severe, life-threatening toxicities. The inhibition of acetylcholinesterase results in hyperactivity within cholinergic nervous system pathways because of the accumulation of the neurotransmitter acetyl choline. This accumulation results in a variety of signs characteristic of hypercholinergic activity, with death in lethal level poisonings resulting from respiratory failure. Paraoxon is a potent anticholinesterase and consequently parathion is a very toxic insecticide (rat oral LD50, 2 mg/kg) (3). The hydrolysis of paraoxon, illustrated in Fig. 1, detoxifies the compound because the hydrolytic products are not acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. In actuality, despite its name, PON1 is not very efficient in hydrolyzing (detoxifying) paraoxon, which is part of the reason that parathion is so toxic (3). Because of its high toxicity, few uses of parathion are approved today. PON1 is far more efficient in hydrolyzing the active metabolites, diazoxon and chlorpyrifos-oxon, of two common OP insecticides, diazinon and chlorpyrifos, respectively, also illustrated in Fig. 1. Both diazinon and chlorpyrifos are considerably less toxic than parathion (rat oral LD50s of 1,250 and 96–270 mg/kg, respectively) (3). The contribution of PON1 to the detoxication of these two insecticides is likely a critical factor contributing to their “safer” acute toxicity levels. In fact, chlorpyrifos-oxon is an extremely potent anticholinesterase, about an order of magnitude more potent than paraoxon, yet chlorpyrifos is roughly two orders of magnitude less toxic than parathion, with much of the difference in potency related to the far greater efficiency of PON1 in detoxication of the two active metabolites (4). The study of Furlong and co-workers in this issue of PNAS (2) used diazoxon as the test compound, a logical choice because of the efficacy of PON1 in the metabolism of diazoxon. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the non-OP compound phenyl acetate is also hydrolyzed by PON1, and two nerve agent structures are provided to show additional OP compounds that are potential substrates for PON1.

Fig. 1.

The hydrolysis of paraoxon, diazoxon, chlorpyrifos-oxon, and phenyl acetate by paraoxonase 1 (PON1), and the structures of the nerve agents sarin and soman. DEP, diethyl phosphate; PNP, p-nitrophenol; IMHP, isopropyl methyl pyrimidinol; TCP, trichloropyridinol.

More recently PON1 has become recognized as a component of the HDL particle and is associated with protection against atherosclerosis. Oxidation of LDLs can initiate the process of atherosclerosis (5), so by preventing the accumulation of oxidized LDLs and HDLs, PON1 can prevent or retard the development of atherosclerosis (1). In laboratory animals, PON1 decreased the generation of lipid peroxides and prevented the formation of fatty streak lesions (6).

The human PON1 gene displays several single-nucleotide polymorphisms, with the Q192R polymorphism being the most significant with reference to catalytic efficiency on various substrates (7, 8). The Furlong laboratory has been one of the leading laboratories in characterizing the human polymorphisms (7, 9, 10). The Q192 form is more effective at hydrolyzing diazoxon, whereas the R192 form is more effective at hydrolyzing paraoxon, and a comparison of the activities with the two substrates has allowed the characterization of individuals into QQ, QR, and RR genotypes. In addition to differences in OP hydrolysis efficiency, the Q192R polymorphism also affects cardiovascular health, with the Q192 form more effective at metabolizing oxidized lipids than the R192 form (10).

PON1 can prevent or retard the development of atherosclerosis.

The study from the Furlong laboratory (2) presents promising technology for the production of engineered forms of human PON1 that could be more effective in detoxifying OP compounds than the naturally occurring Q and R forms. The Q and R forms are quite effective at hydrolyzing diazoxon and chlorpyrifos-oxon, as mentioned above, and undoubtedly PON1 contributes to the relatively low acute toxicity levels of the parent insecticides diazinon and chlorpyrifos. This research altered the critical amino acid residue at the 192 position to lysine (similar to the more effective PON1 found in rabbits) and has increased the efficiency of hydrolysis of diazoxon as well as chlorpyrifos-oxon, paraoxon, and phenyl acetate. Should this variant be more effective at hydrolyzing OP nerve agents that might be used in warfare or by terrorists (such as in the Tokyo subway incident of several years ago; ref. 11), then this technology could provide a mechanism for producing practical quantities of a detoxication enzyme that could be available to save lives, prevent or attenuate seizures, and prevent the long-term damage that sublethal exposures to OP anticholinesterases could cause. The evidence presented in the current paper (2) indicates that the engineered PON1 was nontoxic, was well tolerated by the mice, was observable in the circulation for several days after i.p. injection, and was protective against diazoxon both prophylactically and therapeutically. All of these pieces of evidence point to the potential value of exploring this technology for protection of military personnel or civilians from the OP chemical warfare agents and for protection of agricultural workers and by-standers from accidental poisonings by OP insecticides.

Acknowledgments.

Work on PON in my laboratory was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 ES04394.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 12780.

References

- 1.Gaidukov L, Rosenblat M, Aviram M, Tawfik D. The 192R/Q polymorphs of serum paraoxonase PON1 differ in HDL binding, lipolactonase stimulation, and cholesterol efflux. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2492–2502. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600297-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens RC, et al. Engineered recombinant human paraoxonase 1 (rHuPON1) purified from Escherichia coli protects against organophosphate poisoning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12780–12784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805865105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meister RT, editor. Crop Protection Handbook. Willoughby, OH: MeisterPRO Information Resources; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pond AL, Chambers HW, Coyne CP, Chambers JE. Purification of two rat hepatic proteins with A-esterase activity toward chlorpyrifos-oxon and paraoxon. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:1404–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mertens A, Holvoet P. Oxidized LDL and HDL: Antagonists in atherothrombosis. FASEB J. 2001;15:2073–2084. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson AD, et al. Protective effect of high-density lipoprotein associated paraoxonase: Inhibition of the biological activity of minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2882–2891. doi: 10.1172/JCI118359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies H, et al. The effect of human serum paraoxonase polymorphism is reversed with diazoxon, soman and sarin. Nat Genet. 1996;14:334–336. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Kumar M, Chan W, Berkowitz G, Wetmur JW. Increased influence of genetic variation on PON1 activity in neonates. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1403–1409. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter RJ, Furlong CE. Determination of paraoxonase (PON1) status requires more than genotyping. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:745–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa LG, Cole TB, Jarvik GP, Furlong CE. Functional genomics of the paraoxonase (PON1) polymorphisms: Effects on pesticide sensitivity, cardiovascular disease, and drug metabolism. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:371–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyaki K, et al. Effects of sarin on the nervous system of subway workers seven years after the Tokyo subway sarin attack. J Occup Health. 2005;47:299–304. doi: 10.1539/joh.47.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]