Abstract

Resistance to cell death is a hallmark of cancer. Autophagy is a survival mechanism activated in response to nutrient deprivation; however, excessive autophagy will ultimately induce cell death in a nonapoptotic manner. The present study demonstrates that CCL2 protects prostate cancer PC3 cells from autophagic death, allowing prolonged survival in serum-free conditions. Upon serum starvation, CCL2 induced survivin up-regulation in PC3, DU 145, and C4-2B prostate cancer cells. Both cell survival and survivin expression were stunted in CCL2-stimulated PC3 cells when treated either with the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 (2 μm) or the Akt-specific inhibitor-X (Akti-X; 2.5 μm). Furthermore, CCL2 significantly reduced light chain 3-II (LC3-II) in serum-starved PC3; in contrast, treatment with LY294002 or Akti-X reversed the effect of CCL2 on LC3-II levels, suggesting that CCL2 signaling limits autophagy in these cells. Upon serum deprivation, the analysis of LC3 localization by immunofluorescence revealed a remarkable reduction in LC3 punctate after CCL2 stimulation. CCL2 treatment also resulted in a higher sustained mTORC1 activity as measured by an increase in phospho-p70S6 kinase (Thr389). Rapamycin, an inducer of autophagy, both down-regulated survivin and decreased PC3 cell viability in serum-deprived conditions. Treatment with CCL2, however, allowed cells to partially resist rapamycin-induced death, which correlated with survivin protein levels. In two stable transfectants expressing survivin-specific short hairpin RNA, generated from PC3, survivin protein levels controlled both cell viability and LC3 localization in response to CCL2 treatment. Altogether, these findings indicate that CCL2 protects prostate cancer PC3 cells from autophagic death via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/survivin pathway and reveal survivin as a critical molecule in this survival mechanism.

Extensive research has emerged in recent years revealing the roles of cytokines and chemokines, not only in their involvement in chemotaxis but also in tumorigenesis and cancer cell proliferation, survival, adhesion, and invasion (1-3). The CC class of chemokines, named for the first two conserved cysteine residues, have been shown to be highly involved in mechanisms of tumorigenesis within the skeletal systems, specifically osteoclastic resorption, osteoblast induction, and bone remodeling (4). These cytokine-mediated interactions in the bone microenvironment are critical to the promotion of cell survival and proliferation of metastatic tumors, which inevitably result in patient morbidity and mortality (5-7).

The CC chemokine, CCL2 (MCP-1 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1)), although expressed only at low levels in prostate cancer cell lines, is highly secreted by human bone marrow endothelial cells. It is found in the microenvironment of prostate cancer bone metastases, where it has multiple effects on both tumor and host cells (7). CCL2 dose-dependently induces prostate cancer cell proliferation and invasion (8) and regulates monocyte and macrophage infiltration to prostate cancer epithelial cells, promoting tumorigenesis (9).

Chemokine-mediated signal transduction is initiated through binding to seven-transmembrane domain heterotrimeric G-protein-coupled receptors (10, 11). Specifically, CCL2 interacts with the CCR2B integral membrane receptor, which is responsive to all members of the CC chemokine family (10, 12). The current proposed mechanism suggests that CCL2 stimulation activates a signaling cascade, in which the Gβγ subunits dissociate from the heterotrimeric Gαβγ-receptor complex. Following dissociation, the Gβγ heterodimer will either rapidly activate, by direct interaction, two phosphoinositide-specific lipase isoenzymes, PLCβ2 and PLCβ3, or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)3 γ, resulting in downstream activation of protein kinase C and protein kinase B (Akt) or the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade, respectively (13). In addition, G-protein complex dissociation induces activation of PI3K via the Gα subunit, which, in turn, either activates PKB/Akt via phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473 by PDK1 and PDK2, respectively, or the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade via intermediate cytoskeleton-associated kinases (10, 13, 14). Activation of protein kinase B/Akt thereafter leads to a wide array of downstream functional biological responses that may prolong cell survival, including, but not limited to, induction of endogenous survivin expression (15, 16).

Macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy herein) is a highly evolutionarily conserved catabolic mechanism responsible for the removal and breakdown of cellular materials as a means to maintain intracellular homeostasis (17, 18). Functioning at normal basal levels, autophagy is one of the major mechanisms for the degradation of proteins, macromolecules, damaged organelles, and other unwanted structures (19). However, autophagosome formation can also be stimulated as a response to stresses, such as oxidative damage and nutrient deprivation, functioning to remove protein aggregates and provide required amino acids essential for metabolic processes and cell survival (17, 18). Excessive autophagy will also inevitably trigger autophagic cell death or “type II programmed cell death” (type I programmed cell death being apoptosis). Due to emerging links between autophagic aberrations and cancer, there is rapidly growing support that this type II programmed cell death may also function as a suppressor of tumorigenesis (18).

Autophagic degradation of intracellular materials is initiated by the formation of double membrane-bound vacuoles, termed autophagosomes, which consume part of the cell's cytoplasm, including elements to be degraded. Digestion is completed upon autophagosome maturation, via fusion with endocytic lysosomes. This process requires activation of the downstream product of class III PI3K. Conversely, products of class I PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3,4-biphosphate, and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate exhibit an inhibitory effect (17). When nutrients are abundant, class I PI3K promotes activation of the Ser/Thr protein kinase, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), through receptor tyrosine kinases; mTOR thereby suppresses autophagosome formation (18). On the other hand, LY294002-mediated inhibition of PI3K and negative regulation of mTOR by rapamycin both significantly induce autophagy. mTOR activates downstream Ser/Thr kinase P70S6, which thereafter phosphorylates ribosomal protein S6 (17-19), which is reliably detectable by immunoblotting and serves as an accurate measure of cellular autophagy for this study. During autophagosome formation, cytosolic microtubule-associated protein light chain 3-I (LC3-I) is conjugated with phosphatidylethanolamine and converted to LC3-II. This phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated LC3-II, detectable by immunoblotting, is present specifically on isolation membranes and autophagosomes (20) and therefore serves a second and widely accepted approach to monitoring autophagic flux for this study.

Although CCL2 is widely accepted to play a direct role in inflammation, tumorigenesis, and chemotaxis, its role in cell survival has not been extensively examined. In the present study, we demonstrate that CCL2 confers a distinct survival advantage to PC3 prostate cancer cells by regulation of autophagic death. Furthermore, we have established that CCL2 functions primarily through a PI3K/Akt-dependent pathway following up-regulation of the survival gene, survivin (BIRC5).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines—The androgen-independent human prostate cancer cell lines, PC3 and DU 145 were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen). The human prostate C4-2B cells (UroCor, Inc., Oklahoma City, OK) were derived from LNCaP cells through several passages via castrated nude mice and isolated from the tumor that metastasized to bone (21). The C4-2B cells were maintained in T medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen). Regular passaging was performed at 70-80% confluence by trypsinization, using 1× trypsin and 0.05% EDTA, followed by resuspension in complete medium. Cells were grown and maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2, 95% air atmosphere.

WST-1 Cell Viability Assay—Dye conversion at 440 nm of 4-[3-(4-Idophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-1,3-benzene disulfonate to formazan (Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1; Roche Applied Science) was used to assess cell viability and chemosensitivity of PC3 cells. Cells were grown to 80% confluence and then serum-starved for 16-18 h. Synchronized cells were plated at 104 cells/well into 96-well flat bottom tissue culture plates (catalog number 3596; Costar) and were allowed to attach for 6 h. Cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of inhibitors and/or CCL2 chemokine (Apollo Cytokine Research) or IGF-1 (catalog number 291-G1; R&D Systems) and incubated for 24-168 h. WST-1 reagent was added following the manufacturer's instructions, and plates were returned to 37 °C for 105 min. Dye conversion at an absorbance of 440 nm was ascertained by the VERSAmax Microplate Reader and analyzed using Softmax Pro 3.12 software. The aforementioned technique was applied to dose-response and time course assays to evaluate the effects of the following inhibitors: LY294002 phosphoinsitide-3-kinase inhibitor (catalog number 709920; Cayman Chemical) and Akt inhibitor X (Akti-X; catalog number 124020; Calbiochem) (22). Rapamycin (catalog number 553211; Calbiochem) was also assessed using this technique; however, prior to treatment, PC3 cells were incubated for 24 h, and the cell viability was evaluated 24 h post-treatment.

LIVE/DEAD® Cell Viability Assay—PC3 cells were serum-starved in RPMI 1640 medium for 16-18 h and then plated into Lab-Tek II dual chamber slides (catalog number 155379; Nalge Nunc International) at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/ml. Cells were allowed to attach for 6 h, and CCL2 (100 ng/ml) was added to one chamber of each slide. Cells were then incubated for 24-168 h, and viability of CCL2-treated and untreated PC3 cells was evaluated using the LIVE/DEAD® viability/cytotoxicity kit for mammalian cells (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Immunofluorescence was visualized using an Olympus IX71 microscope. Images were captured using a ×20 objective at 560- and 535-nm excitation wave-lengths and 645- and 610-nm emission wavelengths, respective to each reagent dye.

Real Time PCR—cDNA was generated from control and CCL2-treated PC3 cells at 72 h using the High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (catalog number 4368814; Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real time PCR analysis was performed using Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix (catalog number 4369016; Applied Biosystems) and a survivin-specific Taqman predesigned probe assay (catalog number Hs00977611_g1; Applied Biosystems). Finally, mRNA expression analysis was completed by the University of Michigan Microarray Core Facility, using the ABI 7900 HT sequence detection system.

Western Blot Analysis—Prostate cancer cells (PC3, DU 145, and C4-2B) were grown to 80% confluence on 150-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Falcon) in appropriate medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic. FBS-containing medium was removed, and flasks were washed four times with Hanks' buffered medium (Invitrogen). PC3 and DU145 cells were synchronized by starvation in serum-free RPMI 1640 for 16-18 h at 37 °C. Cells were detached with mild treatment, using 0.25 mm EDTA pH 8.0 (Invitrogen), at 37 °C for 20-25 min, and then plated in either 6-well or 100-mm culture plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/ml. Cells were allowed to attach for 6 h prior to treatment with inhibitors (as specified above) and/or CCL2/IGF-1 (100 ng/ml). C4-2B cells were plated in complete medium, and 16 h later the medium was replaced by serum-free T-medium containing CCL2 (100 ng/ml). After treatment, cells were harvested at increasing time points in radioimmune precipitation cell lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris base, pH 8.0, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 20% SDS, 1 μm okadaic acid, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin). Protein samples were sonicated, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. Supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Protein lysates were electrophoresed through 4-20% Tris-glycine SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride according to the instructions of Invitrogen. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk-TBST (Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary (rabbit) antibodies (Cell Signaling), diluted 1:1000 in blocking solution. 16-24 h later, membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated for 1 h with goat anti-rabbit IgG, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (catalog number 7074; Cell Signaling), diluted 1:2000 in blocking solution. Protein expression was visualized by ECL chemiluminescence (Millipore). Finally, β-actin monoclonal antibody (catalog number 4967L; Cell Signaling) was used as a loading control for all membranes.

Cell Cycle Analysis—PC3 cells were serum-starved in RPMI 1640 for 16 h and then plated (2 × 106 cells/plate) into 100-mm tissue culture plates. Cells were allowed to attach for 6 h. One-half of the plates were then treated with CCL2 (100 ng/ml), and cells from both treated and untreated groups were collected at 48, 72, 96, and 120 h, following standard trypsinization procedure. Collected cells were resuspended in 500 μl of PBS (Invitrogen) and fixed by adding 500 μl of 100% EtOH (equilibrated to -20 °C). Fixed cells were stored for a minimum of 20 min at 4 °C until samples from all aforementioned time points were collected. Following fixation, cells were pelleted, EtOH/PBS was decanted, and cells were resuspended in 500 μl of propidium iodide (PI)-RNase solution (50 μg/ml propidium iodide (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml RNase A (Qiagen), diluted in PBS) and then incubated at room temperature for 20 min. PI-stained samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) with Cell Quest Pro (BD Biosciences) software. Viable cells were gated based upon forward scatter and side scatter parameters. PI fluorescence was detected in the FL2 channel on a logarithmic scale and in the FL3 channel on a linear scale. Voltage adjustments were performed for each sample to place the G0/G1 peak at a standard of 400 on the linear scale. For each sample, 104 events were collected for analysis as the Boolean intersection of viable cells, based upon forward scatter/side scatter gate. Single cell analysis was based upon the FL3 width versus FL3 area doublet discrimination gate. The relative percentages of cells found within each phase of the cell cycle were determined with ModFit LT cell cycle analysis software (Verity House). A linearity factor (G2/G1) of 1.84 was used for all samples. Sub-G0/G1 DNA content (apoptotic cells) was assessed by analysis of PI fluorescence detected in the FL2 channel.

Transient Transfections—PC3 cells were synchronized in 150-cm2 tissue culture flasks, as previously described, and then plated in serum-free RPMI 1640 at 104 cells/well, in 96-well plates. Plates were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 overnight. The following day, cells were transfected with either survivin-specific or nonsilencing siRNA at both 50 and 100 nm, according to instructions provided with the SignalSilence (R) survivin siRNA Kit (catalog number 6350S; Cell Signaling). Cells were transfected in replicates of 10 for each concentration of siRNA. Following transfection, plates were incubated for an additional 24 h. CCL2 (100 ng/ml) was then added, and the cells were further incubated for 72 h. Finally, cell viability was assessed by WST-1 dye conversion, as previously described.

Generation of Stable Cell Lines—Two independent survivin short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) (shS-1 and shS-2; catalog numbers RHS4430-98520325 and RHS4430-99140887, respectively; Open Biosystems) were packaged into lentivirus by the University of Michigan Vector Core, using psPAX2 and pMD2.G mammalian expression lentiviral helper plasmids (catalog numbers 12260 and 12259; Addgene). PC3 cells were trypsinized and seeded at 106 cells/100-mm tissue culture plate in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic. Cells were allowed to grow in complete medium for 24 h. Following incubation, medium was replaced with 10 ml/plate of fresh FBS-containing RPMI 1640. To transfect PC3, 200 μl of each lentiviral shRNA (shS-1 and shS-2, 10× concentrated) was added dropwise to previously seeded cells, in triplicate. Plates were transferred immediately to 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cells were then trypsinized and plated in complete medium, containing 5 μg/ml puromycin (P9620-10ML; Sigma) and incubated for 48 h. Following incubation, cells were washed three times with Hanks' balanced salt solution to remove unattached cells, and medium was replaced with 10 ml of RPMI 1640, containing 2 μg/ml puromycin. Cells were supplemented with this medium every 3-4 days, until GFP-expressing colonies were observed. GFP immunofluorescence was assessed using the Olympus IX71 microscope (×20 magnification) fitted with a 560-nm excitation and 645-nm emission filter. Visible colonies were trypsinized and plated into 100-mm tissue culture plates and then grown to 80% confluence in the presence of 2 μg/ml puromycin prior to cell viability and Western blot analysis, as described above. Stable cell lines were named shS-1 and shS-2, corresponding to transfected survivin shRNA.

Immunofluorescence—PC3, shS-1, and shS-2 cells were serum-starved in RPMI 1640 medium for 16 h at 37 °C and then plated into Lab-Tek II dual chamber culture slides (catalog number 177380; Nunc) and allowed to attach at 37 °C for 6 h. Cells were then either left untreated or treated with CCL2 (100 ng/ml) and incubated for 72 h at 37 °C. Cells were washed briefly with PBS and then fixed with 3% formaldehyde-PBS for 15 min. Fixed cells were then incubated with LC3B primary antibody (diluted 1:200 in PBS/Triton) for 24 h, as per the procedures recommended by Cell Signaling. Following incubation, cells were washed as per the manufacturer's instructions and then incubated with fluorochrome secondary antibodies (diluted 1:200 in PBS/Triton) for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. For parental PC3 cells, AlexaFluor 488-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit IgG (catalog number A11034; Invitrogen) was used as secondary antibody, whereas for shS-1 and shS-2 cells the secondary antibody was replaced by AlexaFluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (catalog number A21245; Invitrogen) to prevent fluorescence interference with the GFP incorporated during stable transfection. Following secondary staining, coverslips were applied with Prolong® Gold Antifade reagent (catalog number P-36930; Invitrogen), and slides were transferred to 4 °C for at least 24 h prior to immunofluorescence analysis. Images were obtained using an Olympus IX-71 FluoView 500 laser-scanning confocal microscope at ×60 magnification with a PlanApo N oil immersion lens, with a numerical aperture of 1.42. Flow View TIEMPO software version 4.3 was used to obtain all Z-stack images and the corresponding maximum intensity projections.

Immunoprecipitation—PC3 cells were grown to 80% confluence and then synchronized for 16 h by serum starvation. 3.5 × 105 cells were plated into 100-mm tissue culture plates (catalog number 83.1802; Sarstedt) and allowed to attach for 6 h at 37 °C. Following attachment, plates were treated or not with CCL2 (100 ng/ml) for 48 h at 37 °C. Cells with or without CCL2 were harvested in 300 μl/plate cell lysis buffer (catalog number 9803; Cell Signaling), containing 1 μm okadaic acid. Cell extracts were obtained by sonication and centrifugation for 20 min at 13,000 rpm. 50 μl of cell lysate from each condition (with or without CCL2) was removed and stored at -20 °C for the analysis of inputs. Samples were precleared for 2 h at 4 °C with 150 μl, per condition, of Dynabeads Protein G (catalog number 100.04D; Invitrogen). After preclearing, survivin rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog number 2808; Cell Signaling) or normal rabbit IgG (catalog number 2729S; Cell Signaling) antibodies were added to cell lysates at 1:100 or 1:200 dilutions and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Dynabeads were washed with cell lysis buffer and placed onto Dynal MPC™ magnets (catalog number 120.20D; Invitrogen) for 2 min to remove wash. Samples were added to washed beads, and the immunoprecipitation was carried out following the recommended procedures of Invitrogen; however, all washes were performed using cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling). Immunoprecipitates and inputs were separated by electrophoresis on a 4-20% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes following standard Western blotting procedure. Membranes were incubated overnight with LC3B antibody (catalog number 2775; Cell Signaling), diluted 1:1000 in 5% milk-TBST, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (catalog number 7074; Cell Signaling). Membranes were also probed with survivin monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling) to verify efficiency and specificity.

Statistical Analysis—All average values are presented as means ± S.E. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software and one-way analysis of variance combined with Bonferroni's test. A probability level of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

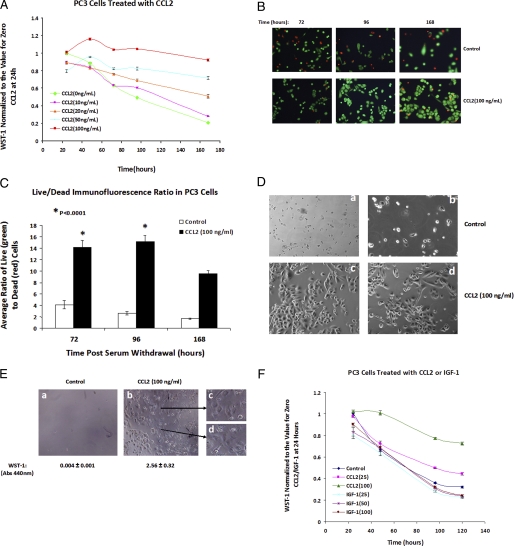

CCL2 Signaling Protects PC3 Cells from Death upon Serum Deprivation—The identification of CCL2-mediated up-regulation in the tumor-bone microenvironment of prostate cancer metastases (7) requires a greater understanding of the role this chemokine plays in the development and progression of prostate cancer. The studies here reveal that CCL2 is a powerful inducer of PC3 cell survival upon serum deprivation. Survival was analyzed at different times by a WST-1 assay. At concentrations of 50 and 100 ng/ml, CCL2 maintained cell viability up to 168 h of serum starvation (Fig. 1A). This result was further corroborated using the Live/Dead® viability/cytotoxicity assay, which allows simultaneous determination of live (green) and dead (red) cells. CCL2 protection from cell death was evidenced by a higher average ratio (3-5 times) of live/dead cells as compared with control cells (Fig. 1, B and C). After 2 weeks, the majority of cells exposed to CCL2 were able to survive in contrast to control cells, suggesting that CCL2 confers an advantage upon PC3 cells to survive in adverse conditions, such as limited nutrients and growth factors (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, after 4 weeks in serum-free medium, CCL2-stimulated cells responded to the readdition of complete medium (10% FBS) by a rapid restoration of the proliferative potential and recovery of the original size and morphology, whereas the control cells were unable to survive (Fig. 1E).

FIGURE 1.

CCL2 signaling prolongs survival in serum-starved PC3 cells, in vitro. A, PC3 cells were synchronized by serum starvation for ∼ 24 h and then treated with increasing concentrations of CCL2 to assess the dose-dependent effects from 0 to 100 ng/ml. Cell viability was evaluated by WST-1 dye conversion at 24-h increments for 96 h and then at 1 week. All absorbences were normalized to untreated (control) samples at the 24 h time point. B, LIVE/DEAD® cell viability assay of both CCL2 (100 ng/ml)-treated and untreated PC3 cells at 72, 96, and 168 h. Viable cells fluoresce at 515 nm (green emission wavelength), and dead cells fluoresce at 635 nm (red emission wavelength). C, quantification of live and dead PC3 cells over time, in response to CCL2 (100 ng/ml) treatment; data shown represent average quantities from six fields at each time point (based on the LIVE/DEAD assay; Fig. 1B). D, PC3 cells were plated into dual well chamber slides (Lab-tek II; Nunc) in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium. One chamber of each slide was treated with CCL2 (100 ng/ml), and cells were incubated without changing medium or further CCL2 supplementation. Following incubation for 14 days, cells were observed using an Olympus FV-500 confocal microscope. Two representative differential interference contrast images for both control (a and b) and CCL2-treated (c and d) cells are shown here. E, cells were treated as described in D; however, cells shown in the differential interference contrast image above were incubated for 4 weeks in serum-free medium. Following incubation, cells were fed by replacing medium with RPMI 1640 + 10% FBS. 72 h after the addition of serum, recovery was observed in CCL2-treated cells; selections from this field have been magnified (c and d) to display cells showing normal PC3 morphology. No viable cells were observed in untreated PC3, following the addition of FBS (left). Cell viability was demonstrated also by WST-1 analysis; corresponding WST-1 absorbance values are shown below each image. F, cell survival curve representing PC3 response to treatment with increasing concentrations of recombinant IGF-1, based on WST-1 dye conversion. Values represent average absorbences of n = 8 samples, normalized to untreated cells at t = 24 h. IGF-1 survival was also compared with PC3 cells treated with two concentrations of CCL2 (25 and 100 ng/ml).

To determine whether prolonged cell survival upon serum deprivation is CCL2 signaling-specific, PC3 survival was assessed by comparison with another factor known to induce Akt activation, IGF-1. The viability of the cells treated with IGF-1 was no different than that of the untreated cells (Fig. 1F), demonstrating that in contrast to CCL2, IGF-1 was unable to induce cell survival. These results also suggest that CCL2 induces specific signals that protect PC3 from cell death upon serum deprivation.

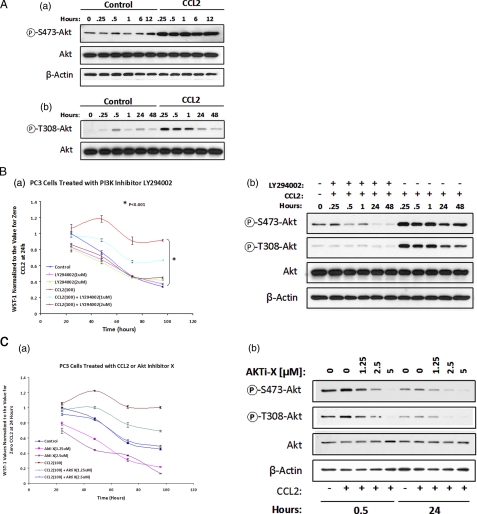

CCL2-mediated Cell Survival Is PI3K/Akt Pathway-dependent—To determine the mechanism involved in CCL2-induced cell survival, we investigated the signaling pathways activated by this chemokine that are critical for cell survival. Previous data have shown that CCL2 induces Akt phosphorylation in prostate cancer cells, a known regulator of cell survival and proliferation, in response to intracellular and extracellular stimuli (7, 23). Full activation of Akt requires the phosphorylation of two key regulatory sites: Ser473 and Thr308. CCL2 induces a rapid (15 min poststimulation) increase in Akt phosphorylation both at Ser473 and Thr308 residues (Fig. 2A (a and b)). Because of a PTEN mutation, these cells exhibit a constitutive Akt phosphorylation; however, our results indicate that a hyperphosphorylation and activation of this molecule takes place upon CCL2 signaling.

FIGURE 2.

CCL2-mediated cell survival is PI3K/Akt pathway-dependent. A, immunoblot analysis of the time-dependent effect of CCL2 (100 ng/ml) on Akt phosphorylation in serum-starved PC3 cells, using anti-P-Ser473Akt (a) and anti-P-Thr308Akt (b) rabbit antibodies (catalog numbers 9271 and 9275, respectively; Cell Signaling). Phosphorylation specificity was evaluated by comparison with total Akt expression for each blot. β-Actin was used as a protein loading control for all blots. B, CCL2 elicits cell survival through a PI3K/Akt-dependent mechanism. Serum-starved PC3 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PI3K/Akt inhibitor (LY294002) in the presence or absence of CCL2 (100 ng/ml). Cell survival analysis, based on WST-1 dye conversion, was performed at 24-h increments over a 96-h time course experiment. a, values depicted in the survival curve above represent average absorbences of n = 5 samples, normalized to untreated cells at t = 24 h. b, Akt phosphorylation at both the Thr308 and Ser473 sites in PC3 cells treated with CCL2 (with or without LY294002 (2 μm)) was evaluated by immunoblot analysis of cell lysates isolated at increasing post-treatment times. Phosphorylation was validated by comparison with total Akt expression. C, Akt inhibitor-X (Akti-X; catalog number 124020; Calbiochem) reduces cell survival over time, in response to serum starvation, and prevents Akt phosphorylation at both the Thr308 and Ser473 sites. Serum-starved PC3 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of Akti-X with or without CCL2. a, cell survival was evaluated at 24-h increments for 96 h by WST-1 dye conversion. The survival curves shown above represent average absorbences (440 nm) of n = 5 samples, normalized to untreated cells at t = 24 h. b, Akt phosphorylation for treated and untreated PC3 cells with or without CCL2 (100 ng/ml), over time, was evaluated by immunoblot analysis and verified by comparison with total Akt expression.

The significance of the PI3K/Akt pathway for cell survival was evaluated in a series of time course experiments by measuring the cell viability in serum-free medium using either LY294002, a PI3K-specific inhibitor (24), or Akti-X, a selective inhibitor of Akt phosphorylation with no effect on PI3K or PDK1 (22). Fig. 2B (a) shows the survival curves for control and CCL2-stimulated cells (100 ng/ml) in the presence of LY294002 using two different concentrations of the inhibitor: 1 and 2 μm. As observed in this figure, LY294002 at 1 μm caused a significant decrease in the viability of CCL2-treated cells, and at 2 μm it completely abrogated the survival induced by this chemokine. However, when the inhibitor was used at this concentration (2 μm) in control cells, it did not cause any further decrease in cell viability. Similar results were obtained with the specific Akt inhibitor, Akti-X (Fig. 2C (a)). When the inhibitor was used at 1.25 μm (IC50 = 2-5 μm; Calbiochem), a decrease in cell viability was observed, and a complete abrogation of CCL2-induced survival was obtained in the presence of Akti-X at 2.5 μm. The inhibition of Akt phosphorylation was confirmed by immunoblotting analysis of cell lysates corresponding to CCL2-treated cells in response to LY294002 (2 μm) or Akti-X (1.25, 2.5, and 5 μm). To detect Akt activation, cell extracts were probed with phospho-Akt-specific antibodies (Ser473 and Thr308). The results shown in Figs. 2B (b) and 2C (b) revealed that both LY294002 and Akti-X effectively inhibited the Akt phosphorylation at both residues. Altogether, these results demonstrate that the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is essential in the cell survival mechanism induced by CCL2.

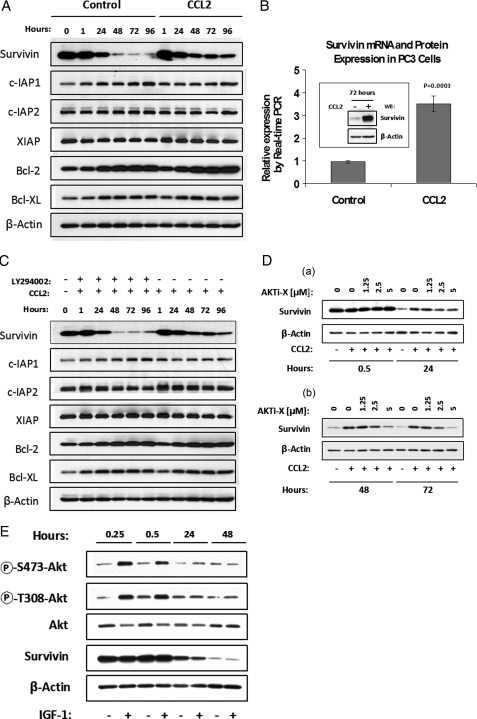

CCL2 Signaling Increases Survivin Expression via a PI3K/Akt-dependent Mechanism—The effect of CCL2 on the expression of the inhibitors of apoptosis (IAP) family proteins was examined by Western blotting. Control and CCL2-stimulated PC3 cells were maintained in serum-free medium up to 96 h, and the cell extracts were collected at increasing time points for analysis with different IAP antibodies: survivin, cIAP1, cIAP2, XIAP, Bcl2, and Bcl-XL. In nonstimulated control cells, the survivin protein levels were dramatically down-regulated after 24 h in serum-free conditions (Fig. 3A). In contrast, survivin was highly up-regulated in CCL2-treated cells when compared with control after 24 h. On the other hand, none of the other analyzed proteins showed a significant change as a result of CCL2 treatment. The antiapoptotic proteins c-IAP1, Bcl2, and Bcl-XL exhibited some up-regulation in time, but no significant differences were observed between control and CCL2 samples.

FIGURE 3.

CCL2 up-regulates survivin mRNA and protein expression via a PI3K/Akt-dependent mechanism. A, immunodetection showing the effect of CCL2 (100 ng/ml) on IAP family proteins in treated and untreated PC3 cells, over time. B, real time PCR analysis of RNA samples, isolated from serum-starved PC3 cells, 72 h following CCL2 treatment. Relative survivin mRNA expression levels represent n = 3 samples. survivin up-regulation, in response to CCL2, was also confirmed by immunoblot analysis of protein lysates collected 72 h post-treatment. C, LY294002 specifically abrogates endogenous survivin expression (with respect to other IAP proteins) in serum-starved PC3 cells, over time, and prevents rescue by treatment with CCL2, as shown by immunoblot analysis. D, immunodetection of protein lysates from serum-starved PC3 cells, treated with increasing concentrations of Akti-X, in the presence of CCL2 (100 ng/ml) at early (a) and late (b) time points. E, the effect of IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) on Akt phosphorylation and survivin expression in serum-starved PC3 cells over time, as determined by immunodetection.

The transcriptional regulation of survivin in response to CCL2 signaling was also explored by real time PCR. Control and CCL2-treated cells were maintained 72 h in serum-free medium prior to mRNA analysis. As shown in Fig. 3B, the real time results from three independent samples of each control and CCL2-stimulated cells evidenced a greater than 3-fold increase in survivin mRNA as a result of CCL2 treatment, suggesting that survivin regulation occurs, to some degree, at the transcriptional level. At this time point, significant up-regulation was also observed in survivin protein (box in Fig. 3B).

Because CCL2-induced survival is PI3K/Akt-dependent, it was reasoned that if survivin were an essential factor in this mechanism, then its up-regulation would also be PI3K/Akt-dependent. To test this hypothesis, CCL2-stimulated cells were treated with or without LY294002 (2 μm) or Akti-X (1.25, 2.5, and 5 μm), and cell lysates were collected for immunoblotting at different times. As shown in Fig. 3C, LY294002 abrogated the CCL2-mediated up-regulation of survivin, resulting in a pattern similar to non-CCL2-stimulated samples, as previously observed (see Fig. 3A). Similarly, the specific Akt inhibitor (Akti-X) evidenced a dose-dependent decrease of survivin protein levels in CCL2-stimulated cells. The survivin down-regulation induced by Akti-X was first observed at 24 h and became more evident at 48 and 72 h (Fig. 3D (a and b)). Thus, survivin up-regulation by CCL2 signaling correlates well with cell survival and is also PI3K/Akt-dependent.

The specificity of CCL2-dependent survivin up-regulation was further assessed by imunoblot analysis of protein lysates from PC3 cells stimulated with IGF-1. Although IGF-1 effectively induced the Akt hyperphosphorylation in these cells, this signaling did not induce survivin up-regulation (Fig. 3E). Since IGF-1 was also unable to induce cell survival (Fig. 1F), these results support the strong correlation between cell survival and survivin expression and further demonstrate the specificity of CCL2 signaling. Furthermore, because IGF-1 activates Akt and the survivin up-regulation induced by CCL2 is PI3K/Akt-dependent, these findings suggest that other signaling molecules may interact or synergize with the Akt signaling pathway to produce the up-regulation of survivin.

Several studies have shown that survivin expression inhibits cell death induced by various apoptotic stimuli in vitro (15, 25, 26) and in vivo (16, 27, 28). This strongly suggests that survivin could be a critical factor in the mechanism of CCL2-mediated survival.

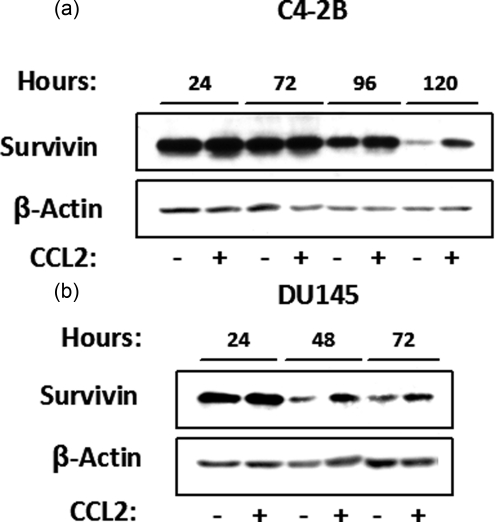

CCL2 Signaling Induces Survivin Up-regulation in Other Prostate Cancer Cells—The effect of CCL2 in survivin regulation was also investigated in C4-2B and DU 145 prostate cancer cells upon serum deprivation. Cell lysates from control and CCL2-stimulated cells were collected at different times for the analysis of survivin protein expression by Western blot. Similar to PC3, upon serum withdrawal, survivin protein levels were dramatically down-regulated in nonstimulated C4-2B and DU 145 cells. However, survivin protein was significantly up-regulated in CCL2-treated cells when compared with control, as observed after 24 h in serum-free medium (Fig. 4, a and b). These results suggest that an analogous mechanism could be activated in other prostate cancer cells.

FIGURE 4.

CCL2 signaling induces survivin up-regulation in other prostate cancer cells in response to serum-starvation. Shown is immunoblot analysis of survivin expression (with or without CCL2 (100 ng/ml)) at increasing times post-treatment, in C4-2B (a) and DU 145 (b) serum-starved cells.

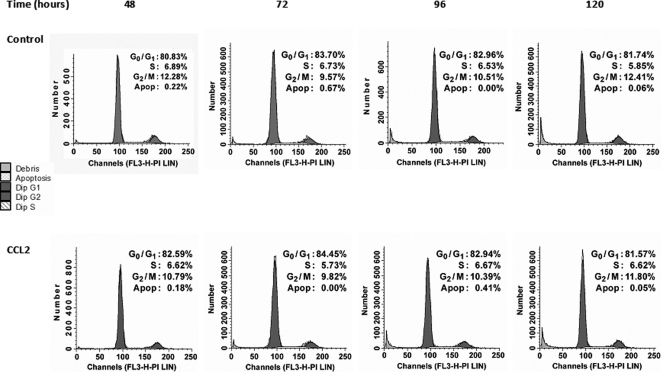

Autophagy Is Activated in PC3 Cells upon Serum Deprivation, and CCL2 Protects Cells from Autophagic Death—Subsequent analysis was focused on identification of the mechanisms of PC3 cell death and CCL2 protection upon serum withdrawal. Apoptosis was assessed at different times (48-120 h) by propidium iodide staining of control and CCL2-treated cells based on the analysis of sub-G1 cell population by flow cytometry. The results evidenced very low apoptotic (hypodiploid) cell populations (less than 1%) and no significant differences between control and CCL2-stimulated cells (Fig. 5). Furthermore, a cell cycle analysis of these populations indicated that the majority of cells were arrested in G1 (about 80%) for both control and CCL2-cells. Additionally, activated caspases were not identified by immunoblot analysis (not shown). Because cellular death was evident in control cells and suppressed by CCL2 (see Fig. 1, A-E), these results imply that the mechanism of death is actually nonapoptotic and caspase-independent. These data correlate with previous reports suggesting that the high level of endogenous Bcl-XL expression protects PC3 cells from apoptotic signals in serum-free medium (29).

FIGURE 5.

Cell cycle analysis of serum-starved control and CCL2-treated cells. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of serum-starved PC3 cells with or without CCL2 (100 ng/ml) based on PI staining at increasing collection times (48-120 h). DNA histograms for each specified time point are representative of three independent cell cycle analyses. Corresponding values for each cell population (G0/G1, S, and G2/M) are expressed as percentages of cells found within each phase of the cell cycle. Sub-G0/G1 populations (apoptotic cells) were also determined and displayed as relative percentages.

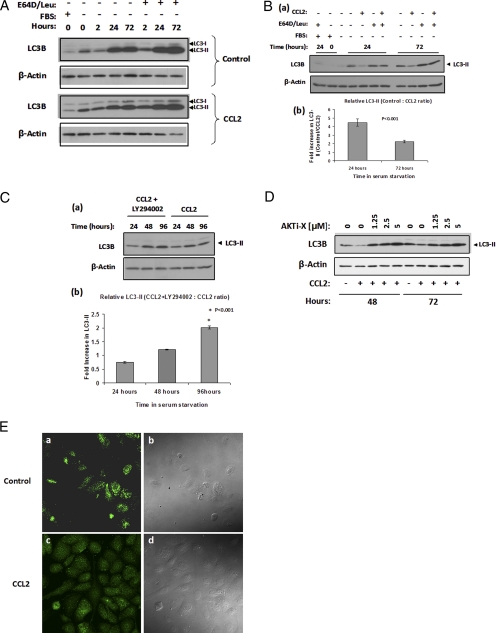

Autophagy, a mechanism activated in response to starvation (30), has the capacity to cause cell death in a nonapoptotic manner and is considered the second most common form of programmed cell death. Microtubule-associated protein LC3 is widely used to monitor autophagy (20). During autophagy, LC3-I is cleaved and conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine to form LC3-II, and this processing is essential for the formation of the autophagosome (31). Since the amount of LC3-II correlates with the number of autophagosomes, it serves as a good indicator of autophagosome formation (31); consequentially, the analysis of autophagy in response to CCL2 was based on LC3 immunodetection. However, because LC3-II itself is degraded by autophagy, the cells were also treated with protease inhibitors (E64d and leupeptin) to detect autophagic flux (20). The results shown in Fig. 6A demonstrated that autophagy was induced both in control and CCL2-stimulated cells: First, the amount of LC3-II was lower in the FBS sample (low autophagy) and increased in time under serum deprivation, suggesting an increase in the number of autophagosomes. Second, a further increase in LC3-II was observed in response to treatment with protease inhibitors (E64d and leupeptin), which served as an indicator of autophagic flux. To determine the possible effect of CCL2 on the extent of autophagosome formation, immunoblot analysis and quantification of LC3-II bands was performed with lysates collected at 24 and 72 h post-CCL2 treatment (Fig. 6B (a and b)). The quantification analysis revealed a significantly lower amount of LC3-II in cells treated with CCL2: more than 4-fold at 24 h and over 2-fold at 72 h. Because the amount of LC3-II correlates with the number of autophagosomes, these results strongly suggest that CCL2 limits the autophagosome formation and, consequently, the overall autophagy in these cells. In addition, Western blot analysis was performed to compare LC3-II protein levels of CCL2-cells in response to LY294002 treatment. The extracts from LY294002-treated cells exhibited a gradual increase in LC3-II when compared with untreated cells (Fig. 6C (a and b)). At 96 h, LC3-II protein was 2-fold higher in CCL2 + LY294002 samples than in CCL2 alone. Similarly, the Akt-specific inhibitor (Akti-X) induced a dose-dependent increase of LC3-II in CCL2-stimulated cells (Fig. 6D). These findings indicate that CCL2 controls autophagosome formation via a PI3K/Akt-dependent pathway, which correlates with CCL2-mediated cell survival and protection from excessive autophagy as a PI3K/Akt-dependent mechanism.

FIGURE 6.

Autophagy is activated in PC3 cells upon serum deprivation and CCL2 regulates the autophagosome formation. A, immunoblot analysis examining starvation-induced autophagosome formation in time, via LC3-II expression, using an anti-LC3B antibody (catalog number 2775; Cell Signaling). Six hours following attachment in serum-free medium, synchronized PC3 cells were treated with or without CCL2 (100 ng/ml). Protease inhibitors leupeptin (catalog number 108975; Calbiochem) and E64D (catalog number 330005; Calbiochem) were also added to the medium where indicated (10 μg/ml each). As a control for nonstarved cells, protein lysate was isolated from cells grown in serum-containing (10% FBS) medium. Both LC3-I (upper band) and its phosphati-dylethanolamine-conjugated form, LC3-II (lower band) are detected by this LC3B antibody. B, a, protein lysates from control and CCL2-treated cells with or without protease inhibitors, described in A, were run in adjacent wells, prior to immunodetection to accurately compare the LC3-II bands at 24 and 72 h. FBS samples were used as a control for non-serum-starved (low autophagy) cells. b, -fold increase in LC3-II expression in untreated versus CCL2-treated cells at 24 and 72 h, post-treatment was quantified and evaluated by densitometric analysis with n = 3 samples, using FluorChem HD2 software (Alpha Innotech). C, a, the effect of the PI3K inhibitor, LY294002 (LY), on LC3-II expression over time, in CCL2-treated cells was determined by LC3B immunoblotting. b, LC3-II -fold increase in CCL2 + LY-versus CCL2-treated cells at 24, 48, and 96 h post-treatment was determined by densitometric analysis with n = 5 samples. For all densitometric quantifications, expression values were normalized to β-actin. D, the effect of Akti-X on endogenous LC3-II, in CCL2-treated cells at 48 and 72 h post-treatment. E, localization of endogenous LC3 upon serum starvation in control and CCL2-treated PC3 cells. The indicated cells were treated or not with CCL2 (100 ng/ml) for 72 h and subjected to immunofluorescence microscopy using a selective antibody against LC3B (Cell Signaling) in combination with goat-anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 488-conjugated IgG, (catalog number A11034; Invitrogen). Maximum intensity projections from Z-stacks obtained by confocal microscopy are shown for control (a) and CCL2-treated PC3 cells (c). Differential interference contrast images of corresponding fields are shown to the right of the respective fluorescent images (b and d).

Upon induction of autophagy, changes in the localization of LC3 occur as a result of its recruitment to autophagic membranes, and these changes are observed as an increase in punctate LC3 (31, 32). LC3 localization in control and CCL2-treated cells was evaluated 72 h poststimulation by immunofluorescence microscopy using the LC3B antibody. As shown in Fig. 6E, control cells (a) evidenced a remarkable increase in LC3 punctae (representing the LC3-II co-localization) as compared with the CCL2-treated cells (b), which exhibited more uniform distribution of the signal as well as lower fluorescence intensity. This result correlates the lower amount of LC3-II detected by Western blot in CCL2-stimulated cells with reduced autophagosome formation.

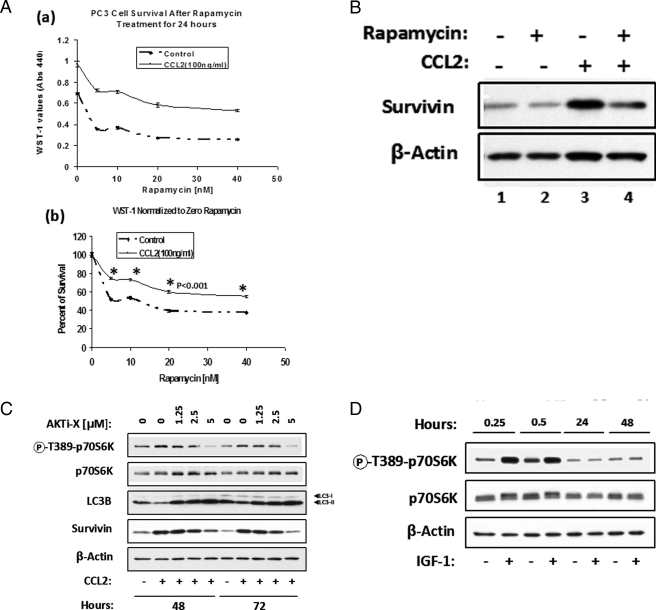

To further support the hypothesis that CCL2 protects PC3 cells from autophagic death, cells were treated with rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTORC1 (mTOR complex 1 or raptor-mTOR complex) and inducer of autophagy (17, 19, 33, 34, 36). In this experiment, cells were plated in serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated as indicated with CCL2 and increasing rapamycin concentrations. The analysis of cell viability 24 h post-treatment is shown in Fig. 7A (a and b). Fig. 7A (a) illustrates WST-1 values for control and CCL2 cells in response to rapamycin. In Fig. 7A (b), the results presented are normalized to 0 nm rapamycin for each condition (with or without CCL2) and expressed as percentage survival. From these results, it can be ascertained that rapamycin increases PC3 cell death and CCL2 provides partial protection from this effect. To investigate a possible correlation between rapamycin-induced cell death and survivin protein levels, a parallel Western blot analysis of these samples was performed as indicated in Fig. 7B. In CCL2-treated cells, it was evident that rapamycin partially abrogated survivin up-regulation (Fig. 7B, lanes 3 and 4); however, in control cells, rapamycin-induced survivin down-regulation was masked due to the low protein expression observed after 48 h in the untreated PC3 (Fig. 7B, lanes 1 and 2). In summary, these findings suggest that survivin plays a critical role in CCL2-mediated protection from autophagic death.

FIGURE 7.

CCL2 protects PC3 cells from autophagic death. A, synchronized PC3 cells were plated in serum-free medium for 24 h prior to treatment with increasing concentrations of rapamycin (0-40 nm) with or without CCL2 (100 ng/ml). Cell viability was assessed by WST-1 dye conversion 24 h post-treatment. a, the survival curves represent the average absorbences (440 nm) of n = 5 samples for each condition with or without CCL2 (100 ng/ml), in response to increased rapamycin concentration. b, the data represented in a were normalized to 0 nm rapamycin for each condition (with or without CCL2) and are expressed as relative percentage of survival. B, a subset of cells treated as described in a with or without 20 nm rapamycin were analyzed by immunoblotting using survivin antibody. C, the effect of Akti-X on phospho-p70S6 kinase (Thr389) in CCL2-treated cells at 48 and 72 h post-treatment by Western blot analysis as compared with LC3B and survivin protein levels. D, IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) induces p70S6K phosphorylation (Thr389) only at early time points in PC3 cells as determined by Western blot analysis of cell lysates, as indicated. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

On the other hand, because mTORC1 negatively regulates autophagy and directly phosphorylates the p70S6 kinase on Thr389 (a residue whose phosphorylation is rapamycin-sensitive in vivo and necessary for S6 kinase activity) (37), it has been proposed that mTORC1 activity (and therefore autophagy) can be monitored by following the phosphorylation of its target protein, p70S6K (32). Consequently, Western blot analysis was performed with lysates from control and CCL2-treated PC3 cells (with or without Akti-X) to detect the p70S6K phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 7C, CCL2 induced higher levels of phospho-p70S6K at both 48 and 72 h post-treatment. The higher phosphorylation of p70S6K correlated with lower LC3-II (as an indication of lower autophagic activity) and higher expression of survivin. Furthermore, the specific Akt inhibitor (Akti-X) induced a dose-dependent decrease of phospho-p70S6K in CCL2-treated cells, correlating with higher LC3-II and lower survivin. In contrast, although IGF-1 was able to induce early (0.25-0.5 h) phosphorylation of p70S6K, stimulation completely disappeared by 24 h (Fig. 7D). These results are consistent with the inability of IGF-1 to protect PC3 from serum deprivation stress (see Fig. 1F).

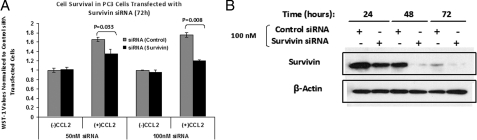

Survivin Is an Essential Factor for CCL2-mediated Survival—The role of survivin in the CCL2-induced survival mechanism was further investigated by transient knock-down experiments using survivin-specific siRNA. PC3 cells were transfected with two different concentrations (50 and 100 nm) of either survivin-specific or nonsilencing siRNA. The cell viability was then analyzed in response to CCL2 stimulation by WST-1 dye conversion. It can be inferred from Fig. 8A that in CCL2-stimulated cells survivin siRNA substantially reduces cell viability as compared with control siRNA (nonsilencing). On the other hand, no major differences were observed in non-CCL2 stimulated cells. Immunoblot analysis of lysates from cells transfected with control and survivin siRNA demonstrated the effectiveness of survivin siRNA to reduce the survivin protein expression (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Analysis of PC3 cell survival in CCL2-treated cells transfected with survivin siRNA. Serum-starved PC3 cells were transfected as described under “Experimental Procedures” with either control (nonsilencing) or survivin-specific siRNA at concentrations of 50 and 100 nm, as indicated. 24 h following transfection, cells were either treated or not with CCL2 (100 ng/ml). A, data represent average WST-1 absorbences (440 nm) obtained from n = 3 samples with or without CCL2 for each transfection condition, 72 h post-treatment. Data shown have been normalized to control (nonsilencing) siRNA-transfected cells; 72 h post-CCL2 treatment. p values for survivin versus control are shown above the respective CCL2 samples. B, immunoblot analysis of control (nonsilencing) and survivin siRNA-transfected PC3 cells at 24, 48, and 72 h post-transfection. Protein lysates were probed with survivin antibody. β-Actin antibody was used as a loading control.

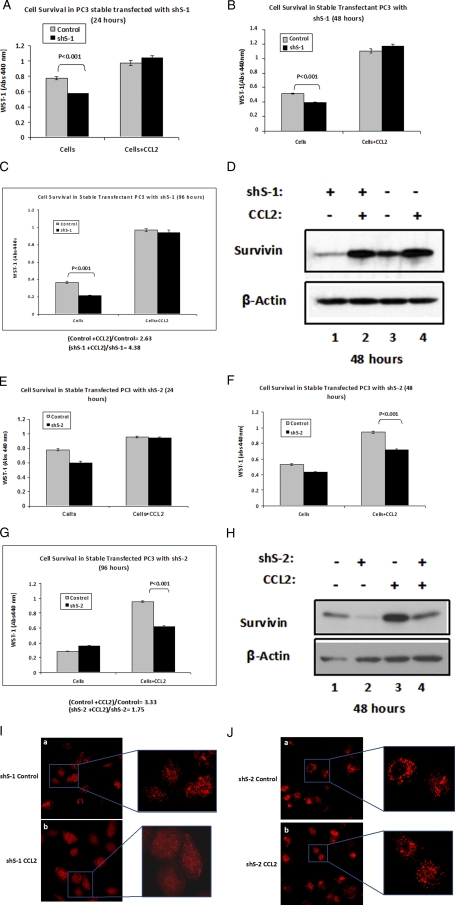

Additionally, two stable cell lines (shS-1 and shS-2) expressing shRNA targeting survivin were generated from PC3. A WST-1 assay was performed to compare the PC3 control with shS-1 and shS-2 cell lines, in response to CCL2 stimulation. Immunoblot analysis of cell extracts from both shS-1 and shS-2 evidenced a reduction in survivin expression, compared with the parental control cells (Fig. 9, D and H). However, some differences were observed between these cell lines upon CCL2 stimulation. Upon CCL2 treatment, survivin expression was restored in shS-1 to similar levels as observed for parental cells (Fig. 9D), and consequently, cell survival was recovered, although untreated shS-1 exhibited reduced viability when compared with control (parental) cells (Fig. 9, A-C). In contrast, CCL2 treatment only partially rescued the survivin levels in shS-2 cells (Fig. 9H), as a result, the cell viability was not restored upon CCL2-stimulation (Fig. 9, F and G). Furthermore, the observed differences in viability between shS-2 and control cells increased with time (from 48 to 96 h) in response to CCL2 stimulation. However, at 24 h, when survivin expression is not yet highly affected by serum starvation (see Fig. 3A), survival was also unaffected by the addition of CCL2 (Fig. 9E). Additionally, shS-1 and shS-2 (with or without CCL2) were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy 72 h post-treatment using the LC3B antibody. As shown in Fig. 9I, the control shS-1 cells evidenced a remarkably higher punctate pattern as compared with CCL2-treated shS-1 cells. The observed difference is consistent with the rescue in survivin expression that occurred in shS-1 after CCL2 stimulation (Fig. 9D, lanes 1 and 2) and correlates with the survival differences between treated and untreated cells (Fig. 9, B and C). In contrast, no major differences were noticed in the immunofluorescence pattern between control and CCL2-treated shS-2 cells (Fig. 9J). In this case, both cell populations showed a similar punctate pattern, consistent with the inability of CCL2 to rescue both cell survival and survivin expression (Fig. 9H).

FIGURE 9.

Analysis of CCL2-mediated survival and LC3 localization in shS-1 and shS-2 stable cell lines. A-C, cell viability of serum-starved parental PC3 (control) and stable-transfected PC3 cells expressing survivin shRNA, shS-1 (catalog number V2LHS_94585; Open Biosystems), in response to treatment with CCL2 (100 ng/ml) was assessed by WST-1 dye conversion at 24 h (A), 48 h (B), and 96 h (C). Data shown represent the average absorbences (440 nm) ± S.E. from n = 5 samples for each group with or without CCL2. D, survivin expression analysis by Western blot of control (parental) and shS-1 stable transfected cells with or without CCL2, 48 h post-treatment. β-Actin was used as a loading control as indicated. E-H, the experiments described in A-D were repeated using a second stable-transfected PC3 cell line expressing shS-2 (catalog number V2LHS_262484; Open Biosystems). E-H correspond to images A-D, respectively. I and J, localization of endogenous LC3 upon serum starvation in control (a) and CCL2-treated (b) cells: shS-1 (I) and shS-2 (J). The indicated cells were treated or not with CCL2 (100 ng/ml) for 72 h and subjected to immunofluorescence microscopy using a selective antibody against LC3B. AlexaFluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (catalog number A21245; Invitrogen) was used as the secondary antibody for the immunofluorescence detection of LC3B. Maximum intensity projections from Z-stacks obtained by confocal microscopy are shown for control (a) and CCL2-treated (b) shS-1 or shS-2 cells. Selections from these fields have been magnified to display the LC3 punctate patterns.

Therefore, survivin protein controls the cell viability and localization of LC3 as a result of its recruitment to the autophagic membranes, suggesting that survivin is a critical factor that mediates the CCL2 protection from autophagic death upon serum starvation.

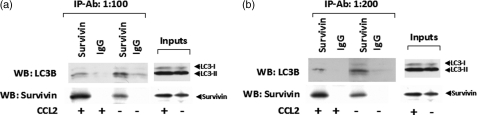

On the basis of these findings, it was hypothesized that survivin might control the extent of autophagy by interacting with LC3. Fig. 10, a and b, shows the results of two independent immunoprecipitation experiments performed with control and CCL2-treated PC3 cell extracts collected 48 h post-treatment. The extracts were immunoprecipitated with survivin or non-specific rabbit IgG antibodies (at two different dilutions), and the immunoprecipitates were probed on Western blot for the presence of LC3B and survivin (positive control). Strong evidence for the association of survivin and LC3 was obtained. Both in control and CCL2 samples, LC3 co-precipitated with survivin antibody. This interaction could be of vital importance in the survivin role of controlling autophagy and protecting the cells upon serum deprivation.

FIGURE 10.

Protein-protein interactions between survivin and LC3B. Two independent immunoprecipitation experiments were performed with control and CCL2-treated PC3 cell extracts collected 48 h post-treatment. The extracts were immunoprecipitated with survivin or nonspecific rabbit IgG antibodies (Cell Signaling) at two different dilutions: 1:100 (a) and 1:200 (b). The immunocomplexes were probed on Western blot for the presence of LC3B and survivin. Immunodetection for survivin was performed to verify immunoprecipitation efficiency and specificity; corresponding blots are shown directly below respective LC3B blots. Input samples for both control and CCL2 lysates are also shown for each immunoblot.

DISCUSSION

Research in cancer biology has demonstrated that various host factors can have a profound effect on cancer behavior. These include inflammatory host responses and immune deficiencies that could reduce the inherent resistance to some cancers. CCL2 plays an important role in the inflammatory response by regulating the recruitment of monocytes/macrophages and other inflammatory cells to sites of inflammation. Several reports have implicated this chemokine in the host activities that impact cancer and have important effects on cancer progression and metastasis (38-42). Indeed, recent data have demonstrated that targeting the CCL2 chemokine with neutralizing antibodies induces prostate cancer tumor regression in vivo (9) and may represent a novel approach to cancer treatment. However, it has not been previously reported that this chemokine may function to directly promote cancer cell survival by protecting these cells from cell death. The data presented here reveal that CCL2 provides a survival advantage to prostate cancer PC3 cells by inhibiting autophagic death, through both activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and up-regulation of survivin.

Upon serum deprivation, cell survival increased in response to CCL2 treatment, reaching a maximum response at 50-100 ng/ml. By measuring cell viability at different times and cell cycle analysis of control and CCL2-treated cells (Fig. 5), it was concluded that PC3 cells are unable to proliferate under serum-free conditions; rather, they exhibit a prolonged resistance to death (>2 weeks) when treated with CCL2. Moreover, upon the readdition of serum, CCL2-treated cells restored the ability to proliferate, even after 4 weeks in serum-free conditions (see Fig. 1E).

A major signaling pathway induced by CCL2 in these cells is the PI3K/Akt pathway. The Akt serine/threonine kinase is a central node in the signaling downstream of growth factors, cytokines, and other cellular stimuli. Several reports have linked Akt to cell survival and inhibition of both apoptotic and nonapoptotic cell death (23, 43). It is also possible that Akt exerts some of its survival effects through cross-talk with other pathways, and it is well known that Akt activates mTOR and vice versa (44, 45). CCL2 stimulation of PC3 cells, upon serum deprivation, results in Akt hyperphosphorylation of the two key regulatory sites (Ser473 and Thr308) required for its full activation. Furthermore, blocking this phosphorylation with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or the Akt-specific inhibitor Akti-X abrogated the CCL2-mediated cell survival.

An important result from the current study is the finding that CCL2 maintains survivin expression by up-regulating both mRNA and protein upon serum deprivation. CCL2-induced survivin up-regulation could be explained, at least in part, by CCL2-dependent transcriptional regulation of this gene, as demonstrated by real time PCR (see Fig. 3B). However, the possibility that CCL2 signaling could also regulate survivin post-transcriptionally cannot be completely ruled out, and future investigations will be needed to address this mechanism.

Numerous reports indicate that survivin expression inhibits cell death induced by various apoptotic stimuli in vitro (25, 46, 47) and in vivo (16, 27, 28). In addition, the Akt pathway has been previously reported to be linked with survivin up-regulation as well as protection of prostate cancer cells from apoptosis (15). Here, CCL2-mediated survivin up-regulation was shown to be PI3K/Akt-dependent; inhibition of this pathway not only abrogated survivin expression but also dramatically decreased cell survival. On the other hand, no significant changes in expression were observed for other members of the IAP family of proteins. These results indicate a strong link between PC3 cell survival and survivin regulation. This study also shows that upon serum deprivation, survivin is up-regulated by CCL2 in other prostate cancer cells, C4-2B and DU145, suggesting an analogous survival mechanism in these cells.

Further significance of survivin overexpression in cancer cells comes from the evidence that it is normally expressed during embryonic and fetal development but undetectable in most normal adult tissues (48). The promoter of the survivin gene is specifically induced during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (49). However, immunohistochemical analysis of tumor samples indicates that survivin may actually be expressed continuously in a cell cycle-independent manner, consistent with the evidence that it is deregulated in cancers. In PC3 cells, CCL2-mediated survivin expression was shown to be cell cycle-independent; after serum starvation, cells are arrested mostly in G1, and no cell cycle progression is apparent (see Fig. 5). Moreover, survivin becomes the fourth most expressed transcript in human cancer (50), where it correlates with a more aggressive disease and reduced overall survival (27).

The data presented here indicate that apoptosis is not the major cell death mechanism induced in serum-deprived PC3 cells. In fact, fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of control and CCL2-treated cells evidenced very low apoptosis (see Fig. 5), and no substantial differences were noticed between the two cell populations (with or without CCL2). These results are consistent with previous reports, showing that in PC3, endogenous Bcl-XL overexpression provides a survival mechanism that protects these cells from apoptotic signals emanating from PI3K inhibition (29).

On the basis of these findings, it was hypothesized that serum-deprived PC3 cells were dying by autophagy. During periods of nutrient shortage, autophagy plays a critical protective role, providing the constituents required to maintain cellular metabolism, and could promote cancer cell survival under metabolic stress (51-53). In most situations, autophagy probably functions initially as a cytoprotective mechanism, but if cellular damage is too extensive or if apoptosis is compromised, excessive autophagy may actually kill the cell (54-56). It was shown here that autophagy is hyperinduced in these cells in response to serum deprivation. In fact, the amount of LC3-II (an indicator of autophagosome formation) increased dramatically within the first 24 h of serum starvation. However, because an increase in autophagy also results in rapid LC3-II degradation, it could lead to misinterpretation of the immunoblot results; therefore, autophagic degradation was evaluated in the presence of protease inhibitors. Here, it was demonstrated that by adding E64D and leupeptin, LC3-II further increased, indicating that autophagic degradation occurs in both control and CCL2-treated cells (Fig. 6A); consequently, the higher LC3-II detected in control cells (Fig. 6B (a and b)) cannot be attributed to an inhibition of autophagic degradation but rather an increase in the autophagosome formation. On the other hand, in CCL2-stimulated cells, the relative number of auto-phagosomes (LC3-II) increased when treated with the PI3K or Akt specific inhibitors: LY294002 and Akti-X (Fig. 6, C (a and b) and D), correlating with a decrease in cell viability (see Fig. 2, B and C). Additionally, the immunofluorescence analysis of LC3 localization evidenced remarkably higher LC3 punctae in control as compared with CCL2-treated cells (Fig. 6E), consistent with LC3-II protein levels detected by Western blot. Altogether, these results suggest that CCL2 signaling limits overall autophagy and, at least partially, protects PC3 cells from death by inhibiting the autophagosome formation.

CCL2 protection from autophagic death was further elucidated by treatment of PC3 cells with rapamycin. Autophagy is controlled by pathways that impinge on mTOR. Activation of mTOR inhibits autophagy, and therefore, treatment with rapamycin induces autophagy (17, 19, 33, 34, 57). The data presented here demonstrated that rapamycin further induced cell death 24 h post-treatment and CCL2 significantly protected cells from rapamycin-induced death (Fig. 7A (a and b)). Furthermore, treatment with rapamycin significantly down-regulated survivin expression (see Fig. 7B), thus further suggesting a link between PC3 cell survival and CCL2 protection from autophagic death, via survivin up-regulation. Moreover, several reports indicate that PI3K/Akt signaling inhibits autophagy (58, 59) and mTOR is regulated through the PI3K/Akt pathway (60). CCL2, but not IGF-1, induced significantly higher phosphorylation of p70S6K at Thr389, detected even at 48 and 72 h post-treatment (Fig. 7D). This phosphorylation was blocked by Akti-X (Fig. 7C), correlating with lower survivin expression and higher LC3-II levels, thus pointing out the crucial role of Akt-mTOR activation in this survival mechanism.

CCL2-mediated survival was substantially reduced by survivin-specific siRNA, compared with control siRNA. Similarly, shS-1, a stable cell line depleted of survivin, exhibited ∼50% reduction in cell viability (at 96 h) as compared with the parental PC3 cell line. Stimulation by CCL2, however, rescued the survivin expression levels, and, as a result, viability was also restored (Fig. 9, A-D). A different result was observed for the survivin-depleted shS-2 stable cell line. Here, the viability of shS-2, as compared with control cells, was slightly lower only at early times (24 and 48 h; see Fig. 9, E and 9); however, by 96 h (Fig. 9G), no substantial differences were observed between shS-2 and control cells. This result could be explained by the pattern of survivin expression; indeed, survivin expression dropped dramatically after 48 h (see Fig. 3A). Consequently, by 96 h, the survivin depletion by shRNA had an insignificant effect. On the other hand, when these cells (shS-2 and control) were stimulated with CCL2, the difference in cell viability became evident at 48 h and further increased by 96 h (Fig. 9, F and G). These findings are consistent with the depletion of survivin observed at 48 h in CCL2-treated shS-2 cells, with respect to CCL2-treated control cells (Fig. 9H, lanes 3 and 4). Furthermore, the findings for LC3 localization by immunofluorescence microscopy correlated with the cell viability and survivin protein levels of shS-1 and shS-2. In fact, LC3 localization (punctate pattern) in shS-1 revealed striking differences when the cells were treated or not with CCL2 (Fig. 9I), a response similar to that observed in parental PC3 cells (Fig. 6E). In contrast, shS-2 cells did not exhibit a different pattern of LC3 localization in response to CCL2 stimulation (Fig. 9J). Altogether, these experiments reveal a strong correlation between cell viability, LC3 localization, and survivin expression in PC3 cells upon serum deprivation. Furthermore, recently LC3 was shown as a mediator of tethering and hemifusion of autophagososme membranes (35), and here, strong evidence for interaction between survivin and LC3 was detected by co-immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 10), suggesting an important link that could be essential in the protection mechanism exerted by CCL2. However, this interaction deserves further investigation to define the exact role of survivin in the control of autophagy.

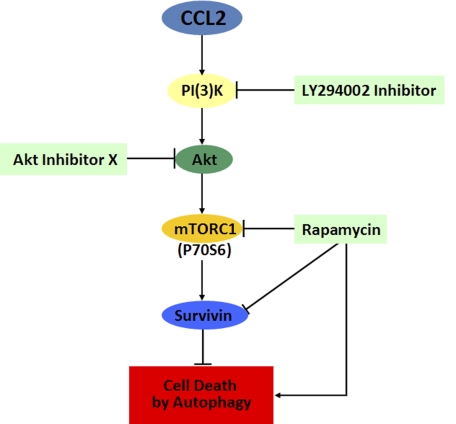

The proposed mechanism for CCL2-mediated inhibition of autophagic death is described in the legend to Fig. 11; CCL2 activates the PI3K/Akt pathway, which in turn mediates the activation of mTORC1, up-regulation of survivin, and down-regulation of autophagosome formation, thus protecting PC3 cells from autophagic death. Conversely, rapamycin down-regulates survivin and hyperactivates autophagy, resulting in increased cell death. This paper, for the first time, reveals survivin as a critical molecule that protects cells from autophagic death. By inhibiting the two major programmed cell death mechanisms, apoptosis and autophagy, survivin becomes a crucial protein that allows cancer cells to survive many cell death stimuli, including nutrient starvation. Accordingly, by up-regulating survivin, CCL2 could suppress both autophagy and apoptosis in cancer cells. In view of our results, we propose combined therapies targeting CCL2 and the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/survivin pathway as a valid strategy to overcome the resistance of prostate cancer cells to death.

FIGURE 11.

Proposed mechanism by which CCL2 induces PC3 cell survival upon serum starvation. CCL2 activates the PI3K/Akt pathway, which in turn mediates the activation of mTORC1, up-regulation of survivin, and down-regulation of autophagosome formation, thus protecting PC3 cells from autophagic death. Conversely, rapamycin down-regulates survivin and hyperactivates autophagy, resulting in increased cell death.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Daniel J. Klionsky for invaluable advice and helpful discussions regarding autophagy. We also thank University of Michigan microarray, BRCF flow cytometry, and shRNA core facilities for technical assistance and especially Joseph Washburn and Timothy Hale for helpful suggestions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NCI, Grant SPORE CA69568-06A1, Comprehensive Cancer Center Core Grant CA 46592-18, and PO1 CA093900. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; LC3, light chain 3; FBS, fetal bovine serum; Akti-X, Akt-specific inhibitor-X; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PI, propidium iodide; siRNA, small interfering RNA; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; IAP, inhibitors of apoptosis; IGF, insulin-like growth factor.

References

- 1.Reiland, J., Furcht, L. T., and McCarthy, J. B. (1999) Prostate 41 78-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talmadge, J. E., Donkor, M., and Scholar, E. (2007) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 26 373-400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charo, I. F., and Taubman, M. B. (2004) Circ. Res. 95 858-866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bar-Shavit, Z. (2007) J. Cell. Biochem. 102 1130-1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logothetis, C. J., and Lin, S. H. (2005) Nat. Rev. Cancer 5 21-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pienta, K. J., and Loberg, R. (2005) Clin. Prostate Cancer 4 24-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loberg, R. D., Day, L. L., Harwood, J., Ying, C., St. John, L. N., Giles, R., Neeley, C. K., and Pienta, K. J. (2006) Neoplasia 8 578-586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu, Y., Cai, Z., Galson, D. L., Xiao, G., Liu, Y., George, D. E., Melhem, M. F., Yao, Z., and Zhang, J. (2006) Prostate 66 1311-1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loberg, R. D., Ying, C., Craig, M., Day, L. L., Sargent, E., Neeley, C., Wojno, K., Snyder, L. A., Yan, L., and Pienta, K. J. (2007) Cancer Res. 67 9417-9424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Boyle, G., Brain, J. G., Kirby, J. A., and Ali, S. (2007) Mol. Immunol. 44 1944-1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter, R., Bistrian, R., Escher, S., Forssmann, W. G., Vakili, J., Henschler, R., Spodsberg, N., Frimpong-Boateng, A., and Forssmann, U. (2005) J. Immunol. 175 1599-1608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jimenez-Sainz, M. C., Fast, B., Mayor, F., Jr., and Aragay, A. M. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 64 773-782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thelen, M. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2 129-134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marino, M., Acconcia, F., and Trentalance, A. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14 2583-2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fornaro, M., Plescia, J., Chheang, S., Tallini, G., Zhu, Y. M., King, M., Altieri, D. C., and Languino, L. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 50402-50411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altieri, D. C. (2008) Nat. Rev. Cancer 8 61-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Codogno, P., and Meijer, A. J. (2005) Cell Death Differ. 12 1509-1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine, B., and Kroemer, G. (2008) Cell 132 27-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pattingre, S., Espert, L., Biard-Piechaczyk, M., and Codogno, P. (2008) Biochimie (Paris) 90 313-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizushima, N., and Yoshimori, T. (2007) Autophagy 3 542-545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu, T. T., Sikes, R. A., Cui, Q., Thalmann, G. N., Kao, C., Murphy, C. F., Yang, H., Zhau, H. E., Balian, G., and Chung, L. W. (1998) Int. J. Cancer 77 887-894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thimmaiah, K. N., Easton, J. B., Germain, G. S., Morton, C. L., Kamath, S., Buolamwini, J. K., and Houghton, P. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 31924-31935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song, G., Ouyang, G., and Bao, S. (2005) J. Cell Mol. Med. 9 59-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, J., Adam, R. M., Santiestevan, E., and Freeman, M. R. (1999) Cancer Res. 59 2891-2897 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dasgupta, P., Kinkade, R., Joshi, B., Decook, C., Haura, E., and Chellappan, S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 6332-6337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang, S., Lim, M., Pham, L. K., Kendall, S. E., Reddi, A. H., Altieri, D. C., and Roy-Burman, P. (2006) Cancer Res. 66 4285-4290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altieri, D. C. (2001) Trends Mol. Med. 7 542-547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanc-Brude, O. P., Yu, J., Simosa, H., Conte, M. S., Sessa, W. C., and Altieri, D. C. (2002) Nat. Med. 8 987-994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang, C. C., Lin, H. P., Chen, C. S., Yang, Y. T., Tseng, P. H., Rangnekar, V. M., and Chen, C. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 25872-25878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine, B., and Klionsky, D. J. (2004) Dev. Cell 6 463-477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabeya, Y., Mizushima, N., Ueno, T., Yamamoto, A., Kirisako, T., Noda, T., Kominami, E., Ohsumi, Y., and Yoshimori, T. (2000) EMBO J. 19 5720-5728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klionsky, D. J., Abeliovich, H., Agostinis, P., Agrawal, D. K., Aliev, G., Askew, D. S., Baba, M., Baehrecke, E. H., Bahr, B. A., Ballabio, A., Bamber, B. A., Bassham, D. C., Bergamini, E., Bi, X., Biard-Piechaczyk, M., Blum, J. S., Bredesen, D. E., Brodsky, J. L., Brumell, J. H., Brunk, U. T., Bursch, W., Camougrand, N., Cebollero, E., Cecconi, F., Chen, Y., Chin, L. S., Choi, A., Chu, C. T., Chung, J., Clarke, P. G., Clark, R. S., Clarke, S. G., Clave, C., Cleveland, J. L., Codogno, P., Colombo, M. I., Coto-Montes, A., Cregg, J. M., Cuervo, A. M., Debnath, J., Demarchi, F., Dennis, P. B., Dennis, P. A., Deretic, V., Devenish, R. J., Di Sano, F., Dice, J. F., Difiglia, M., Dinesh-Kumar, S., Distelhorst, C. W., Djavaheri-Mergny, M., Dorsey, F. C., Droge, W., Dron, M., Dunn, W. A., Jr., Duszenko, M., Eissa, N. T., Elazar, Z., Esclatine, A., Eskelinen, E. L., Fesus, L., Finley, K. D., Fuentes, J. M., Fueyo, J., Fujisaki, K., Galliot, B., Gao, F. B., Gewirtz, D. A., Gibson, S. B., Gohla, A., Goldberg, A. L., Gonzalez, R., Gonzalez-Estevez, C., Gorski, S., Gottlieb, R. A., Haussinger, D., He, Y. W., Heidenreich, K., Hill, J. A., Hoyer-Hansen, M., Hu, X., Huang, W. P., Iwasaki, A., Jaattela, M., Jackson, W. T., Jiang, X., Jin, S., Johansen, T., Jung, J. U., Kadowaki, M., Kang, C., Kelekar, A., Kessel, D. H., Kiel, J. A., Kim, H. P., Kimchi, A., Kinsella, T. J., Kiselyov, K., Kitamoto, K., Knecht, E., Komatsu, M., Kominami, E., Kondo, S., Kovacs, A. L., Kroemer, G., Kuan, C. Y., Kumar, R., Kundu, M., Landry, J., Laporte, M., Le, W., Lei, H. Y., Lenardo, M. J., Levine, B., Lieberman, A., Lim, K. L., Lin, F. C., Liou, W., Liu, L. F., Lopez-Berestein, G., Lopez-Otin, C., Lu, B., Macleod, K. F., Malorni, W., Martinet, W., Matsuoka, K., Mautner, J., Meijer, A. J., Melendez, A., Michels, P., Miotto, G., Mistiaen, W. P., Mizushima, N., Mograbi, B., Monastyrska, I., Moore, M. N., Moreira, P. I., Moriyasu, Y., Motyl, T., Munz, C., Murphy, L. O., Naqvi, N. I., Neufeld, T. P., Nishino, I., Nixon, R. A., Noda, T., Nurnberg, B., Ogawa, M., Oleinick, N. L., Olsen, L. J., Ozpolat, B., Paglin, S., Palmer, G. E., Papassideri, I., Parkes, M., Perlmutter, D. H., Perry, G., Piacentini, M., Pinkas-Kramarski, R., Prescott, M., Proikas-Cezanne, T., Raben, N., Rami, A., Reggiori, F., Rohrer, B., Rubinsztein, D. C., Ryan, K. M., Sadoshima, J., Sakagami, H., Sakai, Y., Sandri, M., Sasakawa, C., Sass, M., Schneider, C., Seglen, P. O., Seleverstov, O., Settleman, J., Shacka, J. J., Shapiro, I. M., Sibirny, A., Silva-Zacarin, E. C., Simon, H. U., Simone, C., Simonsen, A., Smith, M. A., Spanel-Borowski, K., Srinivas, V., Steeves, M., Stenmark, H., Stromhaug, P. E., Subauste, C. S., Sugimoto, S., Sulzer, D., Suzuki, T., Swanson, M. S., Tabas, I., Takeshita, F., Talbot, N. J., Talloczy, Z., Tanaka, K., Tanaka, K., Tanida, I., Taylor, G. S., Taylor, J. P., Terman, A., Tettamanti, G., Thompson, C. B., Thumm, M., Tolkovsky, A. M., Tooze, S. A., Truant, R., Tumanovska, L. V., Uchiyama, Y., Ueno, T., Uzcategui, N. L., van der Klei, I., Vaquero, E. C., Vellai, T., Vogel, M. W., Wang, H. G., Webster, P., Wiley, J. W., Xi, Z., Xiao, G., Yahalom, J., Yang, J. M., Yap, G., Yin, X. M., Yoshimori, T., Yu, L., Yue, Z., Yuzaki, M., Zabirnyk, O., Zheng, X., Zhu, X., and Deter, R. L. (2008) Autophagy 4 151-17518188003 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klionsky, D. J., Meijer, A. J., and Codogno, P. (2005) Autophagy 1 59-60; discussion 60-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noda, T., and Ohsumi, Y. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 3963-3966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakatogawa, H., Ichimura, Y., and Ohsumi, Y. (2007) Cell 130 165-178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blommaart, E. F., Luiken, J. J., Blommaart, P. J., van Woerkom, G. M., and Meijer, A. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 2320-2326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burnett, P. E., Barrow, R. K., Cohen, N. A., Snyder, S. H., and Sabatini, D. M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95 1432-1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leek, R. D., Lewis, C. E., Whitehouse, R., Greenall, M., Clarke, J., and Harris, A. L. (1996) Cancer Res. 56 4625-4629 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohta, M., Kitadai, Y., Tanaka, S., Yoshihara, M., Yasui, W., Mukaida, N., Haruma, K., and Chayama, K. (2002) Int. J. Cancer 102 220-224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali, S. M., and Olivo, M. (2002) Int. J. Oncol. 21 531-540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conti, I., and Rollins, B. J. (2004) Semin. Cancer Biol. 14 149-154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vanderkerken, K., Vande Broek, I., Eizirik, D. L., Van Valckenborgh, E., Asosingh, K., Van Riet, I., and Van Camp, B. (2002) Clin. Exp. Metastasis 19 87-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mochizuki, T., Asai, A., Saito, N., Tanaka, S., Katagiri, H., Asano, T., Nakane, M., Tamura, A., Kuchino, Y., Kitanaka, C., and Kirino, T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 2790-2797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manning, B. D., and Cantley, L. C. (2007) Cell 129 1261-1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarbassov, D. D., Guertin, D. A., Ali, S. M., and Sabatini, D. M. (2005) Science 307 1098-1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olie, R. A., Simoes-Wust, A. P., Baumann, B., Leech, S. H., Fabbro, D., Stahel, R. A., and Zangemeister-Wittke, U. (2000) Cancer Res. 60 2805-2809 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamm, I., Wang, Y., Sausville, E., Scudiero, D. A., Vigna, N., Oltersdorf, T., and Reed, J. C. (1998) Cancer Res. 58 5315-5320 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ambrosini, G., Adida, C., and Altieri, D. C. (1997) Nat. Med. 3 917-921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li, F., Ambrosini, G., Chu, E. Y., Plescia, J., Tognin, S., Marchisio, P. C., and Altieri, D. C. (1998) Nature 396 580-584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]