Abstract

Protein-protein interactions are of critical importance in biological systems and small molecule modulators of such protein recognition and intervention processes are of particular interests. To investigate this area of research, we have synthesized small molecule libraries that can disrupt a number of biologically relevant protein-protein interactions. These library members are designed upon planar motifs, appended with a variety of chemical functions, which we have termed as “credit-card” structures. From two of our “credit-card” libraries, a series of molecules were uncovered which act as inhibitors against the HIV-1 gp41 fusogenic 6-helix bundle core formation, viral antigen p24 formation and cell-cell fusion at low micromolar concentrations. From the high-throughput screening assays we utilized, a selective index (SI) value of 4.2 was uncovered for compound 2261, which bodes well for future structure activity investigations and the design of more potent gp41 inhibitors.

Keywords: “credit-card” library, protein-protein interactions, gp41 fusogenic activation

Introduction

The necessity for therapeutically viable small molecule inhibitors of HIV-1 infection remains as pressing as ever. In the last decade, increased knowledge of viral entry mechanisms has opened the door to the discovery of clinically useful HIV-1 entry inhibitors.1-5 Such molecules can intercept the virus before it invades the cell, unlike most drugs currently in use, which act only after infection occurs.6, 7 HIV-1 entry inhibitors could also be used as prophylactic agents to assemble a barrier against the initial infection. There are a number of protein molecules involved in the viral entry process, on both the host cell and on the virus, providing multiple protein targets for intervention. The viral transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 is of particular interest due to its critical role in viral fusion.8-10

The HIV-1 virus enters a target cell by fusion of the viral envelope and the cell membrane, followed by release of viral genetic material into the cell. This process is mediated by viral envelope (Env) glycoproteins gp120 and gp41, both derived from precursor protein gp160.11 The glycoproteins gp120 and gp41 associate noncovalently to form a quaternary trimeric structure in the viral prefusogenic form, while fusion of the virion with the target cell is triggered by gp120 binding to the CD4 cell surface protein12 and then to one of a group of chemokine co-receptors on CD4+ target cells, such as CXCR4 or CCR5.13 This ligand-receptor binding induces a conformational change in gp120, which thereby converts gp41 to its fusogenic form.8 This cascade of conformational changes positions the gp41 fusion peptide in close proximity to the target cell membrane, leading to viral entry. The gp41 subunit of the HIV-1 Env glycoprotein therefore plays a critical role in mediating viral entry and presents a promising target for the development of viral fusion inhibitors.

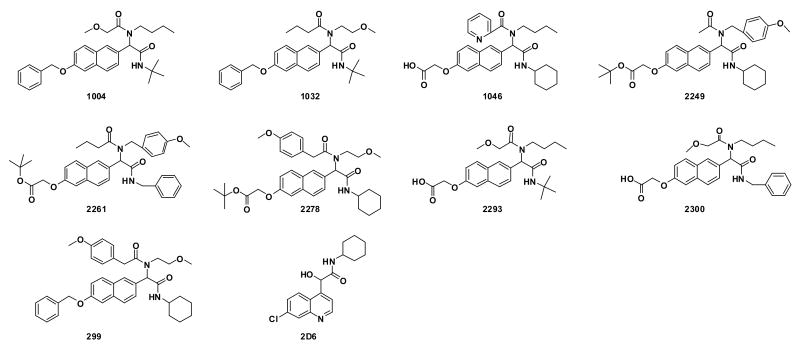

The gp41 protein subunit is comprised of 345 amino acid residues with a molecular weight of 41 kDa, whereas SIV gp41 has a MW of 44 kDa (Scheme 1(a)). The ectodomain of gp41 contains a fusion peptide region marked by both hydrophobic and glycine-rich regions, as well as heptad repeats. These heptads are located adjacent to the N- and C- terminal portions and are designated NHR and CHR, respectively. In the native (i.e., non-fusogenic) state, the fusion peptide is buried in the gp120/gp41 quaternary complex. Upon gp120 binding to CD4 and a co-receptor, the conformational change in gp41 orients the fusion peptide toward the host cell membrane via a “spring-loaded” mechanism similar to the low pH-induced influenza hemagglutinin HA2-mediated membrane fusion process.8 The fusion peptide region is followed by the NHR and CHR terminal regions, which consist of hydrophobic residues predicted to form α-helical coiled-coils. These regions likely mediate the oligomerization and conformational change of gp41 into its fusogenic state. The NHR region is located adjacent to the fusion peptide, while the CHR region precedes this transmembrane segment.

Scheme 1.

(a) primary structure of gp120 and gp41; (b) X-ray crystallography structure of fusogenic gp412. Pink color highlights the N-terminal trimeric structure; Green color highlights C-terminus; Blue color highlights the prominent binding pocket for small molecule fusion inhibitors.

Protein dissection studies, as well as x-ray crystallography, have revealed that the NHR and CHR regions of gp41 co-associate to form a helical trimer of antiparallel dimers in the fusion-active gp41 core domain.2, 14, 15 The inner coiled-coil trimer is formed by the leucine zipper-like heptad repeat sequence, while the outer trimer of C-helices packs in an antiparallel fashion into the grooves on the surface of the inner trimer (Scheme 1B). The C-helix interacts with the N-helix through hydrophobic amino acid residues located in the grooves of the N-helix trimer; these amino acid residues are highly conserved in most HIV-1 viral strains. Molecules that impede the formation of the six-helix bundle could terminate this fusogenic transformation and thereby preclude viral fusion. This hypothesis has been supported by findings that externally added N- and C- terminal peptide fragments of gp41 can inhibit the fusion of HIV-1 or HIV-1-infected cells to uninfected cells.16-18 A gp41 C-terminal peptide, DP178, also known as Enfuvirtide and Fuzeon, is currently in clinical use for treating HIV-1 infection.19 In a recent study, Bianchi et al have demonstrated that a covalently stabilized HIV gp41 N-terminal peptide trimer, (CCIZN17)3, is the most potent fusion inhibitor known to date (IC50 = 40-380 pM).20 While the search for peptide-based fusion inhibitors has been successful, the identification of small molecule HIV viral fusion inhibitors remains elusive. However, this difficulty notwithstanding, the search for small molecule inhibitors is of enormous importance given that small molecule therapeutics almost invariably exhibit improved pharmacokinetic profiles, oral bioavailability, and vastly simpler synthesis scale-up on manufacturing scale relative to synthetic peptide-based therapeutics.9, 10

In an effort to discover small molecule inhibitors targeting gp41 fusogenic activation, Ferrer et al have generated a biased combinatorial chemical library of non-natural binding elements aimed at disruption of the gp41 core association.21 From this library, small molecules were identified that, when covalently attached to a peptide from the gp41 N-terminal peptide, inhibit gp41-mediated cell fusion. Along a similar vein, Jiang et al recently identified a series of small molecules that block the gp41 fusogenic core formation and inhibit HIV fusion.22 Using molecular docking techniques, Jiang et al screened a database of 20,000 organic molecules and found 16 compounds that present a good fit into the hydrophobic cavity within the gp41 core, as well as maximum possible interactions within the target binding site. Following further examination, two of these compounds, ADS-J1 and ADS-J2, displayed inhibitory activity at micromolar concentrations against the formation of the gp41 core structure and on HIV-1 infectivity.10 A notable corroboration of the therapeutic viability of small molecule fusion inhibitors is a recent study from the same group, which revealed that the flavin derivatives in black tea and catechin derivatives in green tea inhibit HIV-1 entry also by targeting gp41.23

We have recently begun exploring the ability of what we have termed “credit card” libraries to disrupt protein-protein interactions of biological relevance.24, 25 The chemical structures of these libraries are grounded upon flat, rigid scaffolds, adorned with functionalities that span a wide range of size, polarity, aromaticity, and hydrogen-bonding capability. The rationale for the design of the library scaffold is based on the concept of the “hot spot” – a region in protein-protein interfaces that are rich in aromatic residues and contribute to the stability of the overall quaternary structure.26, 27 It is our hypothesis that interactions at a hot spot can be disrupted with planar, aromatic compounds that compete for binding, and therefore may efficiently disrupt the assembly. Applying this logic, we have demonstrated that credit card libraries possess members that disrupt c-Myc-Max interactions, a dimerization event that is responsible for tumorigenesis in many types of human cancers.24 Furthermore, with the aid of computational refinement, molecules from this same library have been uncovered as inhibitors against acetylcholinesterase-induced β-amyloid aggregation.25 Herein, we report the identification of compounds from two credit card libraries that inhibit the HIV-1 gp41 fusogenic core formation and HIV-1 replication.

Results

Synthesis of chemical libraries

The credit card libraries were centered upon scaffolds displaying planar, aromatic core structures such as naphthalene and quinoline. The Ugi four-component condensation (4CC) reaction was utilized to introduce functional diversity to the general α-acylamino amide core while a wide range of structural elements were introduced through variation of size, polarity, aromaticity, and hydrogen-bonding capability.

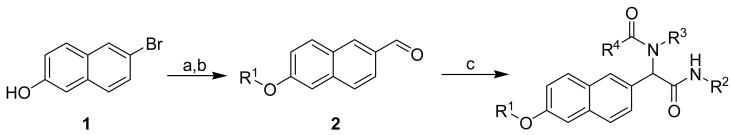

In total, each compound in the naphthalene-based library was synthesized in either two or three steps (Scheme 2). Thus, lithiation of 6-bromo-2-naphthol 1 followed by quenching with DMF afforded the general building block 6-hydroxy-2-naphthaldehyde, which was then treated with a variety of alkyl halides to yield the corresponding phenolic ethers 2. To diversify this scaffold, a mixture of compound 2, isocyanides (R2NC), amines (R3NH2), and carboxylic acids (R4CO2H) were reacted in a parallel fashion to assemble the final α-acylamino amide structure by the Ugi 4CC reaction.28, 29 Overall, 285 individual molecules were prepared in modest to high yields (30-90%) and excellent purity (>95 %) after chromatographic purification. We also note that each compound was prepared in racemic form for the purpose of screening studies.

Scheme 2.

a Synthesis of “credit card” library I based on a naphthalene scaffold.

a Reagents: (a) nBuLi (2 equiv.), THF, −78 °C, then DMF; (b) R1Br, K2CO3, DMF, 60 °C; (c) R2NC, R3NH2, R4CO2H, MeOH/CHCl3, reflux.

To further evaluate the planar region of the “credit card” library molecular scaffold, a quinoline heterocycle, Scheme 3, was also utilized as the aldehyde constituent in the Ugi 4CC. Thus, for credit-card library II, 4,7-dichloroquinoline 3 was treated with iodotrimethylsilane to obtain the chemo-selective iodination product 4. After a selective iodo lithiation and treatment with DMF, the aldehyde 5 was isolated in good yield posed for the Ugi 4CC reaction. For the synthesis of library II, 5 was subjected to the Ugi 4CC reaction with a range of isocyanides, amines and carboxylic acids to grant our second library. A total of 118 molecules were prepared as racemates, and individual purified with high purities (> 95%).

Scheme 3.

a Synthesis of “credit card” library II based on a quinoline scaffold.

a Reagents: (a) TMSI, NaI, Propinonitrile, 90°C; (b) nBuLi (2 equiv.), THF, -78°C, then DMF; (c) R2NC, R3NH2, R4CO2H, MeOH/CHCl3, reflux.

Library selection for the inhibition of fusogenic gp41 core formation and HIV-1-mediated syncytium formation

Both libraries were screened for gp41 fusogenic core formation inhibition activity using a highly sensitive assay, the sandwich Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA), in which the six-helix bundle(6-HB) formed by N36 and C34 was captured by rabbit polyclonal antibodies and detected by a mouse mAb, termed NC-1, which specifically recognizes the discontinuous epitopes on this quaternary complex. The sandwich ELISA was first established by Jiang et al to specifically identify small molecule HIV-1 inhibitors that target gp41.30 The advantage of this assay is its promiscuous detection of all “hits” that block six-helix bundle formation irrespective of inhibitor binding site(s). After screening both libraries at 10 μM per member, we identified 10 compounds with ≥ 50% inhibition, including 2293, 1032, 299, 2300, 1046, 2278, 2249, 2261, 1004, and 2D6. Interestingly, 2D6 from library II was found to be the Passerini adduct and not the expected Ugi 4CC product. The Passerini reaction is a three-component condensation reaction between a carboxylic acid, a carbonyl compound and an isocyanide.31,32 Passerini adducts, α-hydroxy carboxamides, are often observed as byproducts in Ugi 4CC reactions as they share three common reaction components. The Passerini product 2D6 formation in our study can be attributed to the postulation that the t-butyl amine component is too bulky to form the Schiff base with the aldehyde 5 efficiently in the early stage of the condensation reaction, a key step for Ugi 4CC reaction, but not for Passerini 3CC reaction; therefore, Passerini 3CC adduct, 2D6, was produced as the main product for this particular reaction. Excitingly, inhibition was still observed in the six-helix bundle assay using 2D6. This further suggests the planer core does indeed play a major role for the inhibition of protein-protein interactions.

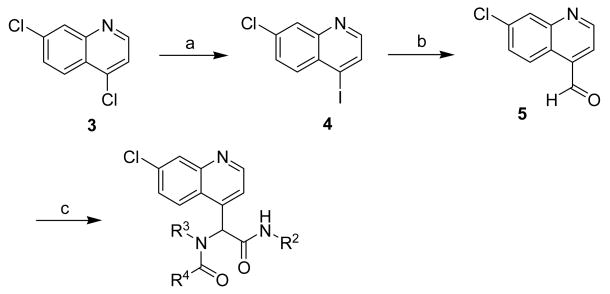

Concurrently, libraries I and II were screened for inhibition of HIV-1-mediated syncytium formation, which is complementary in allowing the detection of HIV-1 induced cell-cell fusion. In this process, one HIV-1 infected cell fuses with multiple uninfected cells to form a syncytium, which is defined as a cell having more than four nuclei and balloon. Strikingly, all the active compounds (vide supra), except 2249, inhibited syncytium formation at 10 μM. From this initial screen, nine molecules emerged from library I while a single molecule was identified from library II; these structures are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Compounds pre-selected from the sandwich ELISA and syncytium formation assays.

The inhibitory activity of the pre-selected compounds as judged by gp41 six-helix bundle formation, HIV-1-mediated cell-cell fusion and HIV-1 replication

The 10 pre-selected compounds were further examined for their inhibitory activity on the gp41 six-helix bundle formation, HIV-1-mediated cell-cell fusion and HIV-1 replication using Enzyme ImmunoAssay (EIA), dye transfer and p24 assays, respectively. In the EIA assay, N36 peptide was first pre-incubated with a selected compound at graduated concentrations, followed by addition of biotinylated C34 peptide.4,33 The mixture was then added to a 96-well polystyrene plate pre-coated with the mAb NC-1. After incubation, SA-HRP and TMB were added sequentially. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured as described (vide infra) and used to calculate the concentration for 50% inhibition (IC50) of six-helix bundle formation. The dye transfer assay is the most rapid screening method for assessing HIV-1 mediated cell-cell fusion, usually requiring only a few hours.34 In this assay, HIV-1 infected cells were labeled with a fluorescent reagent, Calcein-AM, and then incubated with non-infected MT-2 cells in 96-well plates in the presence or absence of compounds tested. After incubating for two hours, the fused and unfused calcein-labeled HIV-1-infected cells were counted under an inverted fluorescence microscope and the percent inhibition of cell-cell fusion and the IC50 values calculated. The inhibitory activity of compounds on infection by laboratory-adapted HIV-1 strains was determined by the p24 assay.35 In brief, MT-2 cells were infected with HIV-1 in the presence or absence of compounds at graduated concentrations overnight. Culture supernatants were collected later from each well, mixed with equal volumes of 5% Triton X-100 and assayed for p24 antigen, which was quantitated by ELISA.36

As shown in Table 1, all 10 compounds inhibited gp41 six-helix bundle formation in a dose-dependent manner with IC50 values ranging from 23 to 47 μM. Compounds 1004 and 2D6 inhibited HIV-1-mediated cell-cell fusion and compounds 1032, 2278, 2249, 2261, and 1004 blocked HIV-1 replication at micromolar levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inhibitory activities of the pre-selected compounds on HIV-1-mediated cell-cell fusion and HIV-1 replication.

| Compound | MW | IC50a for inhibition of 6-HB formation

(μM) |

IC50 for inhibition of cell-cell fusion

(μM) |

IC50 for inhibition of p24 production

(μM) |

CC50b (μM) |

SIc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2293 | 458.55 | 23.42±0.71d | - e | - | >80 | NA |

| 1032 | 490.63 | 25.73±0.04 | - | 18.5±2.5 | 48.0±0.5 | 2.6 |

| 299 | 594.74 | 35.19±2.29 | - | - | >80 | NA |

| 2300 | 492.56 | 42.13±4.18 | - | - | >80 | NA |

| 1046 | 517.62 | 33.20±5.60 | - | - | >80 | NA |

| 2278 | 618.76 | 29.93±14.94 | - | 44.5±7.4 | 45.4±6.7 | 1.0 |

| 2249 | 574.71 | 36.59±2.67 | - | 19.4±4.9 | 43.6±1.6 | 2.3 |

| 2261 | 610.74 | 38.26±2.19 | - | 11.3±2.5 | 47.5±1.0 | 4.2 |

| 1004 | 490.63 | 42.32±6.99 | 40.5±1.2 | 16.8±3.1 | 40.5±0.9 | 2.4 |

| 2D6 | 318.80 | 47.34±2.72 | 15.3±1.2 | - | 35.4±1.6 | NA |

IC50: 50% inhibitory concentration;

CC50: 50% cytotoxic concentration;

Selectivity Index (SI) = CC50/IC50 for inhibiting p24 production;

Mean ± SD;

“-” : <50% inhibition or no detectable inhibitory activity at 80 μM due to cytotoxicity.

Discussion

With the increasing rate of HIV infection worldwide, the development of effective anti-HIV-1 agents is of vital importance. To date, 20 anti-HIV-1 drugs have been licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.37 With the exception of Fuzeon, most anti-HIV drugs target HIV-1 protease and reverse transcriptase. The identification of molecules targeting viral entry has therefore opened a new avenue in the development of novel anti-HIV-1 therapeutics. Cell-permeable small molecules are of particular interest since it is widely acknowledged that small molecules generally afford better oral availability, pharmacokinetics and lower production cost than peptide-based drugs.

We have recently developed a strategy to disrupt protein-protein interactions using “credit card”-like compounds.24 The structural stability of protein-protein interactions derives from large (typically 1,000-3,000 Å2), relatively shallow interfaces. The difficulty of disrupting such expansive interactions with small molecules may be due to (1) the extensively buried surface area on each side of the interface, as well as (2) the lack of deep small cavities that resemble small-molecule-binding sites, as seen from X-ray crystal structures.38,39 However, breakthroughs in breaching protein-protein interactions have occurred with the identification of “hot spots”. Hot spot domains have been characterized as shallow loci of about 600 Å2 found at or near the geometric center of the protein-protein interface. These areas are generally characterized as being rich in aromatic residues such as tryptophan, tyrosine, and histidine. In addition, for many protein-protein interactions, the interface complementarity involves a significant level of protein flexibility and adaptivity.26 There may be binding-site conformations that are well-suited to small molecule binding which are not clearly visible in a single crystal structure. In total, it seems plausible that small, planar, aromatic scaffolds with appended diversity may be able to specifically access these hot spots and thus disrupt stabilizing interactions.

As the name implies, the credit card library members are simply planar, aromatic core structures adorned with chemical diversity. The compounds are intended to function as inhibitors of protein-protein interactions or otherwise alter the necessary interactions at the interface. From these libraries, compounds have been identified as inhibitors that disrupt Myc/Max oncoprotein dimerization and with the aid of computational refinement, we have also identified compounds from the same libraries that inhibit the peripheral anionic binding site of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and reduce the ability of the β-amyloid peptide to aggregate and form fibrils.

The recent identification of a “hot spot” in the fusogenic form of gp41, namely the deep hydrophobic pocket in the groove on the surface of the gp41 internal trimer formed by the NHR domains1,40,41 inspired us to test our library against this target in order to identify molecules with a potential to disrupt this protein assembly. By employing a series of high-throughput screening (HTS) assays, Jiang and colleagues have identified a number of small molecule HIV-1 fusion inhibitors that may dock in the gp41 hydrophobic pocket and block the gp41 six-helix bundle formation, e.g., ADS-J1, NB-2 and NB-64.22, 42 In the present study, we used this same series of high-throughput screening methods to select small molecule inhibitors from our credit card libraries. We first examined our two libraries with a sandwich ELISA using a unique mAb NC-1 which specifically recognize the gp41 core formed by the NHR and CHR or the N- and C-peptides. This assay is optimized to be highly sensitive in order to allow the identification of compounds with minimal inhibitory activity. However, because of its extreme sensitivity, compounds with false-positive activity may also be selected, but these will eventually be excluded in a panel of secondary assays using FLISA, FN-PAGE, N-PAGE, etc.43, 44 In the present study, we corroborated the sandwich ELISA results using a syncytium-formation assay to screen for compounds that inhibit HIV-1-induced membrane fusion.22 Though this assay is not quantitative, it is a sensitive cell-based screening method complementary to the cell-free sandwich ELISA assay. By utilizing these two HTS assays, we identified 10 compounds with inhibitory activity in one or both assays. These pre-selected compounds were further examined for their inhibitory activity on gp41 six-helix bundle formation, HIV-1-mediated cell fusion, and HIV-1 replication using quantitative assays under more stringent experimental conditions. Several of these pre-selected compounds exhibited inhibitory activity in a dose-dependent manner in all of these assays. Of these positive “hits”, five compounds, 1032, 2278, 2249, 2261, and 1004, inhibited 6-helix bundle formation and viral antigen p24 production at low micromolar concentrations, while compound 1004 also inhibited cell-cell fusion at the low micromolar level. To complete these studies, we also tested the in vitro cytotoxicity of these compounds to determine their Selective Index (SI) values; the results have been summarized in Table 1. The Selective Index value, defined as CC50/IC50, has previously been used as a general measurement of the anti-HIV-potency for peptide and/or small molecule inhibitors.10 Using similar HTS assay protocols, two compounds have been reported in the literature, namely ADS-J1 with an SI value of 35.24 and ADS-J2 with an SI value of 9.43. In our study, compound 2261, identified from credit-card library I, displayed and SI value of 4.2 and thus is our most promising compound for future sub-library development for improvement of the SI value determined.

Conclusion

Protein-protein interactions are involved in most cellular processes and are of critical importance. Based on the nature of known protein-protein interactions and the recent identification of “hot spots” located at protein-protein interfaces, we hypothesized that small, planar, aromatic scaffolds with appended diversity may access specific areas at protein-protein interfaces and thus disrupt such interactions. To this end, we have prepared two small molecule libraries, termed “credit card” libraries. From library I, multiple chemical entities were uncovered as Myc/Max dimerization inhibitors, as well as compounds that inhibit the peripheral anionic binding site of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and reduce the ability of the β-amyloid peptide to aggregate and form fibrils. Inspired by the recently described “hot spot” located at the N-terminus of HIV-1 fusion protein gp41, we examined the same libraries in an effort to uncover molecules that inhibit the gp41 fusogenic transformation process.

Using several HTS assays, five compounds, 1032, 2278, 2249, 2261, and 1004, were identified that inhibit six-helix bundle formation and viral antigen p24 production at low micromolar concentrations, while compound 1004 also inhibited cell-cell fusion at the low micromolar level. Although the anti-HIV-1 potency (as evaluated by SI value) of the molecules identified from our studies are not therapeutically viable to be considered as drug candidates, these results provide a valuable class of new lead structures for the designing more potent sub-libraries that target the cell entry process.

Experimental section

General Procedures

The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AMX-400 or Varian Inova-400 instrument. The following abbreviations were used to explain the multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, b = broad. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded at The Scripps Research Institute on a VG ZAB-ZSE mass spectrometer using MALDI. All reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) carried out on 0.25 mm E. Merck silicagel plates (60F-254), with fractions being visualized by UV light. Column chromatography was carried out with Mallinckrodt SilicAR 60 silicagel (40-60 μM). Reagent grade solvents for chromatography were obtained from Fisher Scientific. Reagents were purchased at the highest commercial quality and used without further purification. All reactions were carried out under an argon atmosphere, unless otherwise noted. Reported yields were determined after purification for a homogenous material.

6-(Benzyloxy)-2-naphthaldehyde and tert-butyl 2-(6-formylnaphthalen-2-yloxy)acetate (2a and 2b)

To a stirring solution of 6-hydroxy-2-naphthaldehyde (1.00 g, 5.8 mmol) and K2CO3 (4.0 g, 29 mmol) in DMF (30 mL), either benzyl chloride (6.4 mmol) or tert-butyl bromoacetate (0.87 mL, 6.4 mmol) was added, and the solution stirred at 80 °C. After 2 h, the mixture was diluted with EtOAc (200 mL) and water (300 mL). The phases were separated, and the aqueous layer was washed with EtOAc (200 mL). The combined organics were washed with water, then brine, and dried over MgSO4. Filtration, followed by concentration in vacuo, returned the product as a white solid, which was used without further purification:

6-(Benzyloxy)-2-naphthaldehyde (2a)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.10 (s, 1H), 8.26 (s, 1H), 7.91 (m, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (m, 7H), 5.15 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3)δ 191.99, 167.63, 160.11, 159.87, 138.64, 134.65, 132.84, 131.58, 128.69, 128.22, 124.05, 120.74, 107.80, 70.46, 55.75. ESI-TOF calc. C18H15O2 [M+H+]: 263.1067, found: 263.1061.

tert-butyl 2-(6-formylnaphthalen-2-yloxy)acetate (2b)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.33 (s, 1H), 7.99 (m, 2H), 7.84 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.75 (s, 2H), 1.59 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 192.3, 167.8, 158.6, 138.2, 134.5, 132.8, 131.6, 128.9, 128.5, 123.9, 120.0, 109.7, 107.5, 83.5, 65.9, 28.3. ESI-TOF calc. C17H19O4 [M+H+]: 287.1278, found 287.1274.

7-Chloro-4-iodo-quinoline (4)

To a solution of 4,7-Dichloro-quinoline (12.0 g, 606 mmol) in propionitrile, was added iodo-trimethyl-silane (25.0 g, 1.21 mmol) immediately out of its ampoule, and a small amount of sodium iodide (0.5 g, 3.3 mmol). The resulting orange suspension was heated to reflux at 90° C. After 10 h the reaction was transferred to a separatory funnel and quenched with water (400 mL) and 1M sodium hydroxide (400 mL). After vigorous shaking to separate phases, the aqueous layer was washed with EtOAc (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic layers were then washed with water (1 × 100 mL) and brine (1 × 100 mL), then dried over MgSO4. After filtration and concentration in vacuo, the yellow solid was crystallized in EtOAc:hexanes to give the product as white needles. Obtained =14.9 g, 85% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.39 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.6, 148.0, 136.3, 133.0, 132.6, 129.0, 128.7, 111.4. ESI-TOF calc. C9H6NClI [M + H+]: 289.9228, found: 289.9226.

7-Chloro-quinoline-4-carbaldehyde (5)

A 250 mL Schlenck flask charged with 7-chloro-4-iodo-quinoline (5.18 g, 179 mmol) was vacuum purged 3× with argon, then dry THF (100 mL) was added via syringe. The solution was then cooled to −78° C with acetone:CO2, and 1.6M n-Buli (16.8 mL, 268mmol) was added all at once via syringe. The resulting black solution was stirred 4 minutes, then anhydrous DMF (1.31 g, 179 mmol) was added all at once via syringe. The cooling bath was removed after 15 minutes and the reaction was allowed to warm to r.t. After 2 h the orange solution was quenched with water (50 mL). The reaction was transferred to a separatory funnel and washed with EtOAc (3 × 50mL). The combined organic fractions were then washed with water (1 × 100 mL) then brine (1 × 100 mL) then dried over MgSO4. After filtration the solution was concentrated in vacuo, purified via flash chromatography (eluent 1:3 EtOAc:hexanes), and concentrated once more to a tan solid. Obtained = 2.45 g, 72% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.39 (s, 1H), 9.16 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 8.92 (d, J = 9.0, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 2.1, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 4.2, 1H), 7.61 (dd, J = 9.0 Hz, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 192.52, 151.5, 149.5, 136.6, 136.1, 130.1, 128.7, 126.1, 125.9, 121.9. ESI-TOF calc. C10H7ONCl [M + H+]: 192.0211, found: 192.0209.

General procedure for Ugi four component condensations

To a solution of the naphthal derivative 2 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 eq) in MeOH were added acid (0.4 mmol, 2.0 eq), amine (0.4 mmol, 2.0 eq), and isocyanide (0.4 mmol, 2.0 eq). After stirring for 24 hrs at reflux, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by a short silica gel column packed in a 5 mL Teflon syringe with 10% to 50% EtOAc/hexane gradient to afford the desired product. All products were analyzed by 1H NMR and HRMS. Compounds 1046, 2293, and 2300 are derived from corresponding tert-butyl esters of the Ugi products by TFA deprotection.

2-(6-(benzyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)-N-tert-butyl-2-(N-butyl-2-methoxyacetamido)acetamide (1004)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.92 (s, 1H), 7.81(m, 2H), 7.57 (apparent d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (apparent td, J = 7.5, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (m, 2H), 7.32 (m, 2H), 6.50 (s, 1H), 5.96 (s, 1H), 5.27 (s, 2H), 4.32 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, 1H), 4.23 (d, J = 14 Hz, 1H), 3.56 (s, 3H), 3.38 (m, 2H), 1.61 (m, 2H), 1.58 (m, 2H), 1.43 (s, 9H), 0.74 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.0, 169.9, 157.4, 136.7 (2 × ArC), 134.1, 130.4, 129.7, 128.7, 128.6 (3 × ArCH), 128.1, 127.5 (2 × ArCH), 127.3, 119.6, 106.9, 71.9, 70.0, 62.9, 59.1, 45.8, 38.5, 31.7, 28.6, 20.0, 13.6. ESI-TOF calc. C30H39N2O4 [M+H+]: 491.2904, found: 491.2901.

N-(1-(6-(benzyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)-2-(tert-butylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-N-(2-methoxyethyl)butyramide (1032)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.51 (m, 11H), 6.01 (s, 1H), 5.17 (s, 2H), 3.44 (m, 3H), 3.10 (m, 4H), 2.48 (m, 2H), 1.69 (m, 2H), 1.34 (s, 9H), 0.95 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.7, 169.3, 157.2, 136.6, 134.0, 130.8, 129.7, 128.7, 128.6 (2 × ArCH), 128.5, 128.0, 127.5 (2 × ArCH), 127.4, 127.3, 119.5, 106.8, 70.8, 69.9, 62.8, 58.5, 51.4, 45.7, 35.3, 28.6, 18.6, 13.8. ESI-TOF calc. C30H39N2O4 [M+H+]: 491.2904, found: 491.2906.

tert-butyl 2-(6-(1-(N-butylpicolinamido)-2-(cyclohexylamino)-2-oxoethyl)naphthalen-2- yloxy)acetate

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.28 (s, 1H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.63 (m, 4H), 7.26 (m, 2H), 6.89 (m, 1H), 5.98 (s, 1H), 4.59 (s, 2H), 3.83 (m, 2H), 3.35 (m, 1H), 1.45 (m, 21 H), 0.80 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 0.45 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.6, 167.7, 160.1, 156.1, 153.9, 148.2, 146.9, 137.8, 136.8, 133.8, 130.8, 129.7, 128.5, 127.2, 126.6, 124.9, 118.8, 106.6, 82.3, 65.6, 60.2, 47.9, 45.5, 32.8, 32.5, 31.4, 29.5, 28.0, 25.4, 24.4, 20.6, 14.0. ESI-TOF calc. C34H44N3O5 [M+H+]: 574.3275, found: 574.3271.

2-(6-(1-(N-butylpicolinamido)-2-(cyclohexylamino)-2-oxoethyl)naphthalen-2-yloxy)acetic acid (1046)

1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 8.6 (s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.21 (m, 1H), 7.44 (m, 7H), 5.98 (s, 1H), 5.84 (s, 1H), 4.60 (s, 2H), 3.52 (m, 1H), 3.14 (m, 1H), 2.82 (m, 1H), 0.97 (m, 17H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 172.3, 160.3, 157.9, 154.7, 148.9, 139.9, 135.5, 130.8, 130.6, 128.4, 126.2, 120.2, 117.6, 115.7, 107.8, 65.6, 64.3, 48.3, 33.4 (x2), 31.7, 28.8, 25.7 (x2), 20.6, 13.3. ESI-TOF calc. C30H36N3O5 [M+H+]: 518.2649, found: 518.2654.

tert-butyl 2-(6-(2-(cyclohexylamino)-1-(N-(4-methoxybenzyl)acetamido)-2-oxoethyl)naphthalen-2-yloxy)acetate (2249)

1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 7.55 (m, 3H), 7.12 (m, 3H), 6.70 (apparent d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.43 (apparent d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.11 (s, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 4.61 (s, 2H), 4.43 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (s, 1H), 3.59 (s, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 1.66 (m, 4H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 1.18 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 174.7, 171.2, 169.5, 159.5, 157.5, 135.1, 131.3, 130.6, 130.3, 130.1, 129.8, 129.4, 128.5, 127.7 (x2), 119.6, 114.2, 113.7, 107.5, 80.1, 66.2, 63.5, 55.2, 49.7, 49.0, 33.1, 27.9, 26.2, 25.7. ESI-TOF calc. C34H43N2O6 [M+H+]: 575.3115, found 575.3110.

tert-butyl 2-(6-(2-(benzylamino)-1-(N-(4-methoxybenzyl)butyramido)-2-oxoethyl)naphthalen-2-yloxy)acetate (2261)

1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 7.51 (m, 3H), 7.15 (m, 6H), 6.96 (m, 6H), 6.16 (s, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 4.56 (s, 2H), 4.31 (m, 3H), 3.55 (s, 3H), 2.36 (m, 1H), 2.21 (m, 1H), 1.57 (m, 2H), 1.41 (s, 9H), 0.82 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 177.4, 172.7, 170.0, 159.9, 157.8, 139.7, 135.5, 132.7, 131.4, 131.1, 130.8, 130.1, 129.9, 129.6, 129.5 (x2), 129.3,128.5, 128.2 (x2), 128.1, 120.1, 114.9, 114.6, 107.9, 83.5, 66.6, 64.2, 55.6, 49.9, 44.1, 36.9,28.3, 19.6, 14.3. ESI-TOF calc. C37H43N2O6 [M+H+]: 611.3115, found 611.3098.

tert-butyl 2-(6-(2-(cyclohexylamino)-1-(N-(2-methoxyethyl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)acetamido)-2-oxoethyl)naphthalen-2-yloxy)acetate (2278)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.79 (m, 1H), 7.66 (m, 2H), 7.38 (m, 1H), 7.21 (m, 3H), 7.03 (m, 1H), 6.87 (m, 2H), 5.96 (s, 1H), 4.62 (s, 2H), 3.81 (m, 5H), 3.60 (m, 1H), 3.43 (m, 1H), 3.32 (s, 2H), 3.16 (s, 3H), 3.09 (m, 1 H), 1.42 (m, 19H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 168.7, 167.8, 160.2, 158.4, 156.4, 133.8, 130.8, 130.0 (2 × ArCH), 129.9, 129.0, 128.4, 127.5, 127.3, 127.1, 119.1, 114.2, 114.0, 106.7, 82.5, 70.9, 65.7, 62.9, 58.8, 55.2, 48.5, 46.2, 39.9, 33.2, 32.9, 28.0, 25.4, 25.1, 24.7. ESI-TOF calc. C36H47N2O7 [M+H+]: 619.3378, found: 619.3393.

tert-butyl 2-(6-(1-(N-butyl-2-methoxyacetamido)-2-(tert-butylamino)-2-oxoethyl)naphthalen-2-yloxy)acetate

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 5.83 (s, 1H), 4.60 (s, 2H), 4.20 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 3.44 (s, 3H), 3.23 (m, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H), 1.32 (overlapping s and m, 11H), 0.96 (m, 2H), 0.61 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.0, 169.2, 167.7, 156.3, 133.8, 130.7, 129.8, 128.9, 128.6, 127.5, 127.3, 119.1, 106.7, 82.4, 71.0, 65.6, 62.7, 60.3, 59.0, 51.3, 45.6, 28.8, 28.5, 27.9, 19.9, 13.2. ESI-TOF calc. C29H43N2O6 [M+H+]: 515.3115, found: 515.3112.

2-(6-(1-(N-butyl-2-methoxyacetamido)-2-(tert-butylamino)-2-oxoethyl)naphthalen-2-yloxy)acetic acid (2293)

1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 7.70 (m, 3H), 7.33 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (m, 2H), 5.94 (s, 1H), 5.70 (s, 1H), 4.71 (s, 2H), 4.15 (m, 2H), 3.32 (s, 3H), 3.15 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.25 (s, 9H), 0.82 (m, 4H), 0.44 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 172.6, 171.0, 164.1, 158.3, 135.8, 132.2, 130.9, 130.5, 130.4, 129.3, 128.7, 120.6, 108.2, 72.8, 66.1, 64.2, 59.7, 52.5, 46.4, 29.1, 27.8, 21.0, 13.9. ESI-TOF calc. C25H35N2O6 [M+H+]: 459.2490, found: 459.2485.

tert-butyl 2-(6-(2-(benzylamino)-1-(N-butyl-2-methoxyacetamido)-2-oxoethyl)naphthalen-2- yloxy)acetate

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.80 (s, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (m, 5H), 7.02 (s, 1H), 6.63 (s, 1H), 5.96 (s, 1H), 4.61 (s, 2H), 4.21 (d, J = 13.8 Hz, 1H), 4.15 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (s, 3H), 3.41 (s, 3H), 3.29 (m, 2H), 1.47 (s, 9H), 1.38 (m, 1H), 0.99 (m, 3H), 0.63 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.7, 168.1, 162.1, 156.7, 138.1, 134.2, 130.3, 130.1, 129.2, 129.0, 128.8, 127.9, 127.8, 127.7, 127.6, 119.5, 107.0, 82.8, 71.1, 69.5, 63.4, 59.5, 46.5, 43.9, 31.8, 28.3, 20.1, 13.6. ESI-TOF calc. C32H41N2O6 [M+H+]: 549.2959, found: 549.2954.

2-(6-(2-(benzylamino)-1-(N-butyl-2-methoxyacetamido)-2-oxoethyl)naphthalen-2-yloxy)acetic acid (2300)

1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 7.70 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (m, 1H), 7.33 (m, 2H), 7.16 (m, 7H), 6.04 (s, 1H), 4.70 (s, 2H), 4.23 (m, 2H), 3.92 (s, 2H), 3.32 (s, 3 H), 3.14 (m, 2H), 1.22 (m, 1H), 0.76 (m, 3H), 0.42 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, MeOD-d3) δ 174.0, 172.6, 172.5, 158.1, 139.9, 135.6, 131.4, 130.8, 130.5, 130.3, 129.9, 129.6, 129.5, 128.7, 120.4, 107.9, 70.1, 65.8, 64.0, 59.5, 46.1, 44.3, 31.1, 20.8, 13.6. ESI-TOF calc. C28H33N2O6 [M+H+]: 493.2333, found: 493.2334.

2-(6-(benzyloxy)naphthalen-2-yl)-N-cyclohexyl-2-(N-(2-methoxyethyl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)acetamido)acetamide (299)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39 (m, 15 H), 5.94 (s, 1H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 3.79 (overlapping s and m, 5H), 3.58 (m, 1H), 3.42 (m, 1H), 3.30 (s, 2H), 3.13 (s, 3H, 3.06 (m, 1H), 1.46 (m, 10H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.2, 168.9, 158.4, 157.3, 136.6, 134.1, 130.5, 129.9 (2 × ArCH), 129.7, 128.7, 128.6 (2 × ArCH), 128.4, 128.0, 127.5 (2 × ArCH), 127.4, 127.3, 127.0, 119.6, 114.2, 114.0, 106.9, 70.9, 70.0, 66.4, 58.2, 55.2, 48.5, 46.2, 41.0, 33.1, 33.0, 30.9, 25.3, 24.7. ESI-TOF calc. C37H43N2O5 [M+H+]: 595.3166, found: 595.3161.

2-(7-Chloro-quinolin-4-yl)-N-cyclohexyl-2-hydroxy-acetamide (2D6)

1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.91 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.84 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 5,92 (s, 1H), 3.40 (m, 1H), 1.90-1.10 (m, 10H). 13C NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.2, 158.4, 152.5, 141.8, 136.9, 132.8, 129.5, 128.4, 128.1, 122.6, 72.0, 55.9, 35.4, 26.7, 25.6. ESI-TOF calc. C17H19ClN2O2 [M + H+]: 319.1135, found; 319.1130.

Sandwich ELISA for screening for inhibitors of the gp41 core formation

A sandwich ELISA as previously described 30 was used to screen for compounds that inhibit the gp41 six-helix bundle formation. Briefly, peptide N36 (2 μM) was pre-incubated with a test compound at the indicated concentrations at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by addition of C34 (2 μM). After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, the mixture was added to wells of a 96-well polystyrene plate (Costar, Corning Inc., Corning, NY) which were precoated with IgG (2 μg/ml) purified from rabbit antisera directed against the N36/C34 mixture. Then, the mAb NC-1, biotin-labeled goat-anti-mouse IgG (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), streptavidin-labeled horseradish peroxidase (SA-HRP) (Zymed, S. San Francisco, CA), and the substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (Sigma) were added sequentially. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using an ELISA reader (Ultra 384, Tecan, Research Triangle Park, NC). The percent inhibition by the compounds was calculated as previously described35.

Screening for HIV-1 fusion inhibitors by syncytium-formation assay

HIV-1IIIB-infected H9 cells (H9/HIV-1IIIB) at 2 × 105/ml were cocultured with MT-2 cells (2 × 106/ml) in the presence of compounds to be screened (final concentration of compound: 25 μg/ml) in a 96-well plate at 37 °C for 2 days. HIV-1 induced syncytium formation was observed under an inverted microscope and scored as “+” (no syncytium was observed), “±” (syncytium formation was partially inhibited), and “-” (syncytium formation was not inhibited). The compounds scored with “+” and “±” were selected for further study.

Measurement of the inhibitory activity of compounds on the gp41 six-helix bundle formation

An enzyme immunoassay (EIA) was used for measuring the inhibitory activity of compounds on the gp41 six-helix bundle formation. Briefly, peptide N36 (2 μM) was pre-incubated with a selected compound at graded concentrations at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by addition of biotinylated C34 (2 μM) and incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. The mixture was added to wells of a 96-well polystyrene plate (Costar, Corning Inc., Corning, NY) which were precoated with the mAb NC-1. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, SA-HRP and TMB were added sequentially. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured as described above. The percent inhibition and the concentration for 50% inhibition (IC50) was calculated using the software designated Calcusyn45, kindly provided by Dr. T. C. Chou (Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY).

Assessment of inhibitory activity of compounds on HIV-1 replication

The inhibitory activity of compounds on infection by laboratory-adapted HIV-1 strains was determined as previously described33 8. In brief, 1 × 104 MT-2 cells were infected with HIV-1 at 100 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infective dose) in 200 μl of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS in the presence or absence of compounds at graded concentrations overnight. For the time-of-addition assay, compounds were added at various time post-infection. Then the culture supernatants were removed and fresh culture media were added. On the fourth day post-infection, 100 μl of culture supernatants were collected from each well, mixed with equal volumes of 5% Triton X-100 and assayed for p24 antigen, which was quantitated by ELISA34. Briefly, the wells of polystyrene plates (Immulon 1B, Dynex Technology, Chantilly, VA) were coated with HIVIG in 0.085 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 4 °C overnight, followed by washes with PBS-T buffer (0.01M PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20) and blocking with PBS containing 1% dry fat-free milk (Bio-Rad Inc., Hercules, CA). Virus lysates were added to the wells and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After extensive washes, anti-p24 mAb (183-12H-5C), biotin labeled anti-mouse IgG1 (Santa Cruz Biotech., Santa Cruz, CA), SA-HRP and TMB were added sequentially. Reactions were terminated by addition of 1N H2SO4. Absorbance at 450 nm was recorded in an ELISA reader (Ultra 384, Tecan). Recombinant protein p24 (US Biological, Swampscott, MA) was included for establishing standard dose response curve.

HIV-1-mediated Cell-cell fusion

A dye transfer assay was used for detection of HIV-1 mediated cell-cell fusion as previously described16, 40. H9/HIV-1IIIB cells were labeled with a fluorescent reagent, Calcein-AM (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) and then incubated with MT-2 cells (ratio = 1:5) in 96-well plates at 37 °C for 2 hrs in the presence or absence of compounds tested. The fused and unfused calcein-labeled HIV-1-infected cells were counted under an inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany) with an eyepiece micrometer disc. The percent inhibition of cell-cell fusion and the IC50 values were calculated as previously described16.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. James Farmer and Jinkui Niu at the MicroChemistry Laboratory of the New York Blood Center for peptide synthesis. This work was supported by Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and NIH grant RO1 AI46221 to S.J. We also thank the NIH AIDS Reagent Repository for providing HIV-1IIIB, MT-2 cells, HIV-1IIIB chronically infected H9 cells (H9/HIV-1IIIB), anti-p24 mAb (183-12H-5C), and HIV immunoglobulin (HIVIG).

References

- 1.Chan DC, Chutkowski CT, Kim PS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15613–15617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM, Kim PS. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ketas TJ, Klasse PJ, Spenlehauer C, Nesin M, Frank I, Pope M, Strizki JM, Reyes GR, Baroudy BM, Moore JP. Aids Research And Human Retroviruses. 2003;19:177–186. doi: 10.1089/088922203763315678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu SW, Jiang SB. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:1827–1843. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore JP, Doms RW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10598–10602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932511100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauci AS. Nat Med. 2003;9:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pomerantz RJ, Horn DL. Nat Med. 2003;9:867–873. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan DC, Kim PS. Cell. 1998;93:681–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang S, Siddiqui P, Liu S. Drug Discovery Today: Therapeutic Strategies. 2004;1:497–503. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang SB, Zhao Q, Debnath AK. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:563–580. doi: 10.2174/1381612024607180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SSL. Intervirology. 1996;39:242–248. doi: 10.1159/000150524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sattentau QJ, Moore JP, Vignaux F, Traincard F, Poignard P. J Virol. 1993;67:7383–7393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7383-7393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger EA, Murphy PM, Farber JM. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu M, Kim PS. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1997;15:465–471. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1997.10508958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang SB, Lin K, Strick N, Neurath AR. HIV-1 Inhibition By A Peptide. Nature. 1993;365:113–113. doi: 10.1038/365113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wild C, Oas T, McDanal C, Bolognesi D, Matthews T. J Cell Biol. 1993:222–222. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wild CT, Shugars DC, Greenwell TK, McDanal CB, Matthews TJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9770–9774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen RY, Kilby JM, Saag MS. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2002;11:1837–1843. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.12.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianchi E, Finotto M, Ingallinella P, Hrin R, Carella AV, Hou XS, Schleif WA, Miller MD, Geleziunas R, Pessi A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12903–12908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502449102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrer M, Kapoor TM, Strassmaier T, Weissenhorn W, Skehel JJ, Oprian D, Schreiber SL, Wiley DC, Harrison SC. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:953–960. doi: 10.1038/13324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang SB, Lu H, Liu SW, Zhao Q, He YX, Debnath AK. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4349–4359. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4349-4359.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu SW, Lu H, Zhao Q, He YX, Niu JK, Debnath AK, Wu SG, Jiang SB. Biochimi Biophys Acta-Gen Subj. 2005;1723:270–281. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Y, Shi J, Yamamoto N, Moss JA, Vogt PK, Janda KD. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;14 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.11.052. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dickerson TJ, Beuscher AE, Hixon MS, Yamamoto N, Xu Y, Olson AJ, Janda KD. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14845–14853. doi: 10.1021/bi051613x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bogan AA, Thorn KS. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:1–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg T. Chembiochem. 2004;5:1051–1053. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ugi I, Meyr R. Angew Chem-Int Ed. 1958;70:702–703. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domling A, Ugi I. Angew Chem-Int Ed. 2000;39:3169–3210. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3168::aid-anie3168>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang SB, Lin K, Zhang L, Debnath AK. J Virol Methods. 1999;80:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(99)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passerini M. Gazz Chim Ital. 1921;51:126. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Passerini M. Gazz Chim Ital. 1921;51:181. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang S, Boyer-Chatenet L. Antiviral Res. 2002;53:A69–A69. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raviv Y, Viard M, Bess J, Blumenthal R. Virology. 2002;293:243–251. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang S, Lin K, Neurath AR. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1557–1563. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Q, Ernst JT, Hamilton AD, Debnath AK, Jiang SB. Aids Research And Human Retroviruses. 2002;18:989–997. doi: 10.1089/08892220260235353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Clercq E. Med Chem Res. 2004;13:439–478. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arkin MR, Wells JA. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2004;3:301–317. doi: 10.1038/nrd1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gadek TR, Nicholas JB. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01479-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ji H, Shu W, Burling FT, Jiang SB, Lu M. J Virol. 1999;73:8578–8586. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8578-8586.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou GF, Ferrer M, Chopra R, Kapoor TM, Strassmaier T, Weissenhorn W, Skehel JJ, Oprian D, Schreiber SL, Harrison SC, Wiley DC. Bioorg Med Chem. 2000;8:2219–2227. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Debnath AK, Radigan L, Jiang SB. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3203–3209. doi: 10.1021/jm990154t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu SW, Boyer-Chatenet L, Lu H, Jiang SB. J Biomol Screen. 2003;8:685–693. doi: 10.1177/1087057103259155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu SW, Zhao Q, Jiang SB. Peptides. 2003;24:1303–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chou TC, Hayball MP. CalcuSyn: Windows software for dose effect analysis. BIOSOFT; Ferguson, MO 63135 USA: 1991. [Google Scholar]