Abstract

We have cloned from rat brain the cDNA encoding an 89,828-Da kinesin-related polypeptide KIF3C that is enriched in brain, retina, and lung. Immunocytochemistry of hippocampal neurons in culture shows that KIF3C is localized to cell bodies, dendrites, and, in lesser amounts, to axons. In subcellular fractionation experiments, KIF3C cofractionates with a distinct population of membrane vesicles. Native KIF3C binds to microtubules in a kinesin-like, nucleotide-dependent manner. KIF3C is most similar to mouse KIF3B and KIF3A, two closely related kinesins that are normally present as a heteromer. In sucrose density gradients, KIF3C sediments at two distinct densities, suggesting that it may be part of two different multimolecular complexes. Immunoprecipitation experiments show that KIF3C is in part associated with KIF3A, but not with KIF3B. Unlike KIF3B, a significant portion of KIF3C is not associated with KIF3A. Consistent with these biochemical properties, the distribution of KIF3C in the CNS has both similarities and differences compared with KIF3A and KIF3B. These results suggest that KIF3C is a vesicle-associated motor that functions both independently and in association with KIF3A.

INTRODUCTION

Neurons are highly polarized cells containing an elaborate microtubule network upon which are transported many types of membrane vesicles involved in the delivery of material to axonal and dendritic terminals (Brady, 1991; Hirokawa, 1991; Schnapp, 1997). Axonal microtubules are oriented uniformly with their plus-ends pointed toward the synaptic terminal (Heidemann et al., 1981), whereas dendrites contain microtubules of mixed orientation (Baas et al., 1988). In axons, transport toward microtubule minus-ends is driven primarily by cytoplasmic dynein (Paschal and Vallee, 1987; Schnapp and Reese, 1989; Schroer et al., 1989) and, to a lesser extent, by the carboxy-terminal type kinesin KIFC2 (Hanlon et al., 1997; Saito et al., 1997). In dendrites the minus-end motor is less clear and may include cytoplasmic dynein and KIFC2 (Saito et al., 1997). Plus-end–directed transport is driven by kinesin and at least ten kinesin-related proteins (KRPs) (Vale et al., 1985b; Coy and Howard, 1994; Kondo et al., 1994; Nangaku et al., 1994; Noda et al., 1995; Okada et al., 1995). Unlike cytoplasmic dynein, which may associate with many types of membrane compartments (Lacey and Haimo, 1994; Muresan et al., 1996), the different kinesin-related motors are proposed to bind selectively to specific types of vesicles (Coy and Howard, 1994; Hirokawa, 1996). This selective targeting is likely to be directed by amino acid sequences that lie outside of the conserved ∼350-amino acid motor domain that defines the kinesin superfamily (Stewart et al., 1991; Aizawa et al., 1992).

Most of the known neuronal kinesins are multisubunit protein complexes [see Hirokawa (1996) for review]. Two of them, conventional kinesin and the KIF3A/3B complex (Cole et al., 1992, 1993; Kondo et al., 1994; Rashid et al., 1995; Wedaman et al., 1996; Yamazaki et al., 1995; 1996), show striking similarities in their structural organization [reviewed in Scholey (1996)]. Both are assembled from two kinesin or kinesin-related polypeptides, each containing a globular motor domain, a central dimerization region, and a globular carboxy-terminal domain to which accessory polypeptides are attached. However, while kinesin consists of two identical heavy chains and two associated light-chain isoforms (Vale et al., 1985b; Bloom et al., 1988; Kuznetsov et al., 1988; Hirokawa et al., 1989), the KIF3A/3B complex is a heterotrimer consisting of two distinct but related motor subunits (KIF3A and KIF3B) and a single, larger accessory protein (KAP3) (Cole et al., 1992, 1993; Yamazaki et al., 1995, 1996; Wedaman et al., 1996). It has been suggested that the KIF3A/3B motor complex functions as an anterograde axonal motor for an otherwise uncharacterized vesicle population (Kondo et al., 1994; Yamazaki et al., 1995); the accessory protein might regulate the binding of the motor to membranes (Wedaman et al., 1996; Yamazaki et al., 1996). The functional importance of heterodimerization of two different motor polypeptides (instead of homodimerization, as in conventional kinesin) is unclear. Since no free KIF3A or KIF3B subunits were found in vivo, it is assumed that most, if not all, of the native KIF3A/3B motor is in the heterotrimeric form (Cole et al., 1993; Cole and Scholey, 1995; Yamazaki et al., 1995, 1996).

We have cloned and characterized from rat brain a novel KRP, KIF3C, which is most closely related to KIF3B. KIF3C exists in two different molecular complexes. Like KIF3B, KIF3C is present in neurons in association with KIF3A. Unlike KIF3B, KIF3C is also part of another complex that does not include KIF3A. These distinct biochemical properties of KIF3C are likely to be related to the rather different localization in the CNS of KIF3C compared with KIF3A and KIF3B. Our results suggest that this heteromeric family of kinesin motors has a broad and complex role in vesicle transport in neurons and other cell types. In a complementary study, Yang and Goldstein (1998) report on the cloning and characterization of KIF3C from mouse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and Analysis of Sequence and Secondary Structure of KIF3C

A λ-ZAP II rat forebrain cDNA library was screened with affinity-purified anti-HIPYR antibody (Sawin et al., 1992), and two overlapping clones (14 g and 17d) were found to encode together a novel KRP which we named KIF3C (see below). The cDNA clones were sequenced on both strands using the automated DNA sequencer of the Sequencing Facility at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). Sequence analysis of the cDNA and protein was done with the LASERGENE Navigator DNA analysis software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). The same software was used to compare protein sequences by diagonal dot matrix plot analysis. The probability of coiled-coil formation was calculated by the algorithm of Lupas et al. (1991), using the ISREC Bioinformatics Group coils software (Swiss Institute for Experimental Cancer Research, Epalinges, Switzerland).

Fusion Protein Expression and Antibody Production

A 639-base pair (bp) fragment corresponding to amino acids 363–576 from the coiled-coil region of KIF3C (which included a domain highly divergent from both KIF3A and KIF3B) was subcloned into pQE30 (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) to generate an amino-terminal 6-His–tagged fusion protein. Antibodies to the purified protein were produced in rabbits (Berkeley Antibody, Richmond, CA) and were affinity purified against the fusion protein according to Rodionov et al. (1991) and stored in borate buffer at pH 8.4. Antibodies to other regions of KIF3C were also generated but were not used in the present study.

An antibody to rat KIF3B was obtained in a similar manner against a fusion protein containing 135 amino acids from a region close to the carboxy terminus of the molecule and was used after affinity purification.

Control immunoglobulin G (IgG) fractions, depleted of specific antibody, were produced by adsorbing IgG preparations obtained from immune sera against the fusion protein used as antigen.

Preparation of Tissue and Cell Extracts

All buffers used in these studies were supplemented with 1 mM dithiothreitol and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Muresan et al., 1996). Tissues were collected from 5-wk-old male Sprague Dawley rats (killed by asphyxiation with CO2), placed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.3, and homogenized immediately, or frozen and stored in liquid N2 until further processing. Tissues were homogenized with a Teflon homogenizer (20 strokes) in 10 ml/g tissue of acetate buffer (100 mM K-acetate, 150 mM sucrose, 5 mM EGTA, 3 mM Mg acetate, 10 mM K-HEPES, pH 7.4) (Niclas et al., 1994). Crude homogenates were centrifuged for 10 min at 5,000 × g. Samples of supernatants were mixed 4:1 with 5× sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, adjusted to equal protein concentration, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Optic nerve tissue and freshly dissected retina were cut into small pieces, homogenized in a minimal amount of buffer in an Eppendorf tube with a small Teflon pestle, and then supplemented with an equal volume of 2× sample buffer and boiled.

Cells, grown in large dishes, were briefly rinsed with PBS, and then collected in PBS and solubilized in sample buffer. DNA was sheared by several passages through a 27G 1/2 needle before boiling. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Subcellular Fractionation

Rat brains were collected in ice-cold PBS and homogenized with a Teflon homogenizer in 10 volumes of either K-HEPES buffer (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM K-aspartate, 40 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.2) (Okada et al., 1995) or 0.25 M sucrose in BRB80 buffer (80 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.8) containing protease inhibitors. All further steps were conducted at 4°C. A postnuclear supernatant (S1) was obtained by two consecutive 10-min centrifugations at 3000 × g. S1 was then fractionated into a medium speed (10-min, 14,000 × g) pellet (P2) and supernatant (S2). The latter was centrifuged for 90 min at 120,000 × g to obtain a high-speed pellet (P3) and supernatant (S3). In some cases, pellets were extracted for 1 h at 4°C with 1.25% Triton X-100, in the presence or absence of 1 M KCl. The extracted material was brought to 2.2 M sucrose and overlaid with 1.8 M sucrose and buffer alone. After centrifugation for 90 min at 120,000 × g, the bottom, middle, and top layers were collected and processed for SDS-PAGE.

For vesicle fractionation, the brain tissue was homogenized in 2 volumes of buffer, and the homogenate was separated into a pellet and medium- to high-speed supernatant by centrifugation for 45 min at 40,000 × g. This step eliminated all heavy membranes and unbroken synaptosomes from the supernatant, leaving behind the lighter membranes, including transport vesicles. These membranes were then recovered as a pellet after a 2-h centrifugation at 120,000 × g. The pellet was briefly washed and resuspended in buffer and adjusted to 35% Nycodenz (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). This fraction was overlaid with six layers of buffer containing decreasing Nycodenz concentrations (30%, 25%, 20%, 15%, 10%, and 0%), and centrifuged for 17 h at 120,000 × g. Twenty fractions were collected from the bottom to the top, with fraction 1 corresponding to the initial 35% Nycodenz load. Samples of equal volume from each fraction were precipitated with methanol/chloroform/water (Wessel and Flugge, 1984) and resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

Microtubule-binding Assay and Preparation of Motor-enriched Fraction

Triton X-100 (2%)–extracted rat brain homogenate, prepared in BRB80, was diluted 1:1 with BRB80 and cleared by a 45-min centrifugation at 120,000 × g. Taxol-stabilized microtubules (assembled from phosphocellulose-purified bovine brain tubulin) were added to the supernatant at final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, and the mixture was supplemented with taxol to 20 μM, 5′-adenylyl imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP) to 5 mM, and MgCl2 to 5 mM. After a 1-h incubation at 23°C, microtubules were sedimented through a 30% sucrose cushion by centrifugation (1 h, 120,000 × g, at 18°C). Pellets were resuspended and incubated in BRB80 containing either 100 mM NaCl or 100 mM NaCl plus 7.5 mM ATP and MgCl2. Supernatants and pellets of extracted microtubules were obtained after centrifugation in the conditions described above. Samples from all steps of the assay were analyzed by Western blotting. In some experiments, ATP releases (i.e., motor-enriched fractions) were subjected to sucrose density gradient centrifugation or two-dimensional electrophoresis as described below.

Sucrose Density Gradient Sedimentation and Immunoprecipitation

Sucrose density gradient centrifugation was performed according to Martin and Ames (1961). Samples of a cytosolic fraction enriched in microtubule motors (see above) were loaded over 5–20% sucrose density gradients prepared in K-HEPES or BRB80 buffer and centrifuged for 15 h, at 120,000 × g (Beckman [Fullerton, CA] SW55Ti rotor, 4°C). Fractions were collected from the bottom of the tube and analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of different motor proteins.

Immunoprecipitations from cytosol or sucrose density gradient fractions were done with affinity-purified antibodies (for KIF3C and KIF3B) or ascitic fluid (for KIF3A), in either native or denaturing conditions. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments from cytosol were performed according to the procedure of Elluru et al. (1995), employing 0.25% Triton X-100 during incubation with antibody and washing of precipitated material with 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.01% SDS, and 500 mM NaCl. In some cases, samples were solubilized in 1% SDS, boiled for 10 min, and mixed with 9 volumes of buffer containing 0.25% Triton X-100 before immunoprecipitation. These conditions dissociated the KIF3C/3A complex. Immunoprecipitated material was collected on Protein A-Sepharose-4B (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA) and then processed for SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Immunoblotting and Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

SDS-PAGE in 7.5% and 3–20% gradient gels, semidry protein transfer onto 0.2-μm polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and antibody overlay were done as previously described (Muresan et al., 1996). Antibody binding was visualized with 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis adapted to minigels was performed according to a modification (Bennett and Reed, 1993) of the method of O’Farrell (1975), using pH 3–10 ampholines (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). First dimension gels were run for 5 h at 500 V. Protein concentration of electrophoretic samples was determined with the dotMETRIC protein assay (Geno Technology, St. Louis, MO).

Immunocytochemistry

Rat Brain Immunocytochemistry.

Six male Sprague Dawley rats (275–325 g) were deeply anesthetized with an i.p. injection of chloral hydrate (7%, 1 ml/100 g body weight) and subsequently perfused with 0.9% NaCl followed by 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The brains were removed from the skulls and immersed in 20% sucrose overnight. A freezing microtome was used to cut 40-μm sections in the coronal plane. The tissue sections were stored in PBS containing 0.02% sodium azide and kept frozen until staining. Free floating sections were incubated in solutions of affinity-purified antibodies appropriately diluted in PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 and 3% normal goat serum for 24–48 h at room temperature. After this and all other incubation steps, the tissue sections were rinsed three times for 10 min each in PBS. Sections incubated with antibodies to KIF3C and KIF3B were incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) diluted 1:500 in PBS plus Triton X-100 and goat serum for 1–1.5 h at 23°C. For KIF3A staining, biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG was used in this step. After rinsing in PBS, tissue sections were incubated in avidin-peroxidase complex (Vector ABC Elite kit, Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:500 in PBS for 1–1.5 h, and reacted in 0.05% diaminobenzidine (Sigma) and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide.

After staining, sections were mounted on gelatin-coated glass microscope slides, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions, cleared in xylene, and coversliped with Permaslip (Alban Science, St. Louis, MO). Slides were viewed under bright field optics, and photomicrographs were taken with color slide film (Kodak Ektachrome 100). After development, film was digitized with a film scanner (Nikon coolscan). Images were edited for sharpness and brightness with Adobe Photoshop and printed on a dye sublimation printer (Kodak 8600) at 300 dpi.

Frozen Tissue Sections.

Rat eyes were collected in ice-cold PBS, enucleated, and placed in PBS containing 4% formaldehyde for 90 min at 23°C. Eyecups where washed in PBS, transferred successively to buffers containing increasing sucrose concentrations, and finally embedded by freezing in a 2:1 mixture (vol/vol) of 20% sucrose-PBS and Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN) (Barthel and Raymond, 1990). Seven-micrometer sections were collected on Superfrost/Plus microscope slides (Fischer Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), air-dried, and kept at −20°C until use.

Cultured Cells.

Hippocampal neurons, cultured at low density on coverslips, were fixed for 20 min in PBS containing 4% formaldehyde and 4% sucrose, permeabilized in ethanol (Goslin et al., 1988), and stored in PBS at 4°C until use. In some cases, cells were first extracted for 15 min at 37°C with BRB80 buffer containing 10 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 4% polyethylene glycol and either 0.02% saponin or 1% Triton X-100, and then fixed for 15 min in methanol at −20°C.

In preparation for immunolabeling, fixed cryosections and cultured cells were blocked for 1 h at 23°C in PBS containing 1% BSA, 5% normal serum (goat or donkey), and 0.05% Triton X-100. Incubations in primary antibodies, appropriately diluted in blocking solution, were carried out overnight at 4°C. In double labeling experiments, incubations with the additional primary antibody were done for 1 h at 37°C. In all double labeling experiments, combinations of a polyclonal and a monoclonal antibody were used. Primary antibodies were detected with rhodamine- and fluorescein-labeled secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) (added simultaneously in double-labeling experiments). Control experiments were done with preimmune IgG fractions or immune IgG fractions adsorbed against the antigen, used at the same IgG concentration as immune antibodies.

Digital micrographs were taken on a Zeiss Axiophot microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), equipped with a Sony color CCD video camera, and collected using Northern Exposure image analysis software (Empix Imaging, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Images were transferred to Adobe Photoshop and edited for contrast and brightness. Micrographs from control experiments were identically processed.

Antibodies

The following rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used: SK-394 (affinity purified), raised to the N-terminal 394 amino acids of squid kinesin heavy chain (Muresan et al., 1996), cross-reacts with kinesin heavy chain and several KRPs in rat tissues; anti-HIPYR antibody (affinity purified), raised to a synthetic peptide corresponding to a conserved region of the kinesin motor domain (Sawin et al., 1992) (gift of Dr. Timothy Mitchison, Harvard Medical School); anticysteine strings protein 1 (CSP1), raised against recombinant CSP1 (Chamberlain and Burgoyne, 1996) (gift of Dr. Robert Burgoyne, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, U.K.); anti-TRAP-α (endoplasmic reticulum marker; Hartmann et al., 1993) (gift of Dr. Tom Rapoport, Harvard Medical School). Antibodies MC1 (anti-synaptophysin), MC17 (anti-synaptotagmin), MC21 (anti-SNAP25), and J (anti-rabphilin) were a gift from Dr. Pietro De Camilli (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT). The following mouse monoclonal antibodies were used: antisynaptobrevin (VAMP) (Cl 10.1) (Baumert et al., 1989), and anti-rab3A/B/C (Cl 42.1), raised against recombinant rab3A (Matteoli et al., 1991) (gift of Dr. Reinhard Jahn, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Yale University School of Medicine); K2.4, from mice immunized with sea urchin kinesin II (Cole et al., 1993; Henson et al., 1995), detects primarily the 85- kDa component of kinesin II, and cross-reacts with a protein doublet corresponding to KIF3A in Western blots of rat tissue extracts (gift of Dr. Jonathan Scholey, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA); anti-SV2 (Buckley and Kelly, 1985) (gift of Dr. Kathleen Buckley, Harvard Medical School; 5F9, anti-MAP2 (dendritic marker; Kosik et al., 1984), and 5E2, anti-tau (Galloway et al., 1987) (gift of Dr. Kenneth Kosik, Harvard Medical School). A monoclonal antibody to heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) was from Sigma.

RESULTS

Cloning and Characterization of KIF3C, a Novel Member of the KIF3 Family of Kinesin Motors

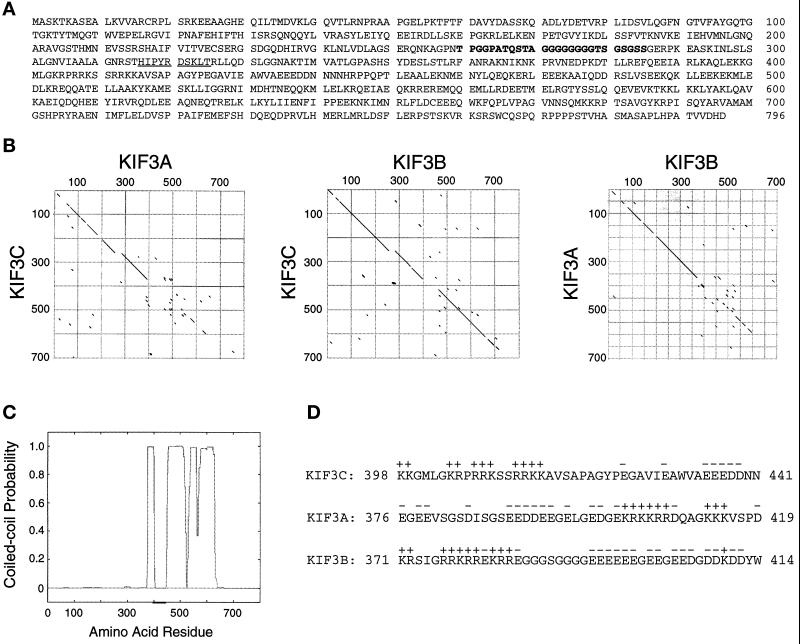

To identify novel neuronal KRPs, we screened a rat forebrain cDNA library with a pan-kinesin peptide antibody (Sawin et al., 1992). We isolated two overlapping clones that encode a protein of 796 amino acids (Mr = 89,828 Da), which we call KIF3C. KIF3C has an amino-terminal globular head containing a kinesin-like motor domain (residues 1–374), a central stalk domain (residues 375–634), and a globular tail domain (residues 635–796) (Figure 1A). KIF3C shows the highest homology to mouse brain KIF3B (61.2% identical) and KIF3A (40.6% identical) (Figure 1B), two closely related kinesin polypeptides that exist as a heterodimer (Kondo et al., 1994; Yamazaki et al., 1995). Within their motor domains, KIF3C is 70.9% similar to KIF3B, and 56.1% similar to KIF3A. In the tail domain, the similarity between KIF3A and KIF3B is low, while KIF3C and KIF3B are 65.5% identical with the exception of a unique region of 79 amino acids at the carboxy terminus of KIF3C (Figure 1B). Analysis of the stalk domain of KIF3C by the algorithm of Lupas et al. (1991) indicated a high probability of forming an α-helical coiled-coil (approximately between residues 375 and 634) (Figure 1C), suggesting that this region may be involved in dimerization. As in the case of KIF3A and KIF3B (Rashid et al., 1995), a small region situated in a discontinuity of the coiled-coil domain contains an unusual segregation of positively and negatively charged amino acids that could create an electrostatic repulsion between molecules that would prevent KIF3C homodimerization. Interestingly, the distribution of charges in this region of KIF3C is similar to that of the corresponding region of KIF3B and opposite to the charge distribution in KIF3A (Figure 1D). Therefore, electrostatic interactions would destabilize a dimer of KIF3C and KIF3B but favor a KIF3C/KIF3A dimer (see below).

Figure 1.

KIF3C is a novel member of the KIF3 family of kinesins. (A) Amino acid sequence predicted from the full-length cDNA. The sequence recognized by the anti-peptide antibody used in library screening is underlined. A 26-amino acid sequence from the motor domain of KIF3C, missing in KIF3A and KIF3B, is shown in bold. The nucleotide sequence of KIF3C is available from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession number AJ223599. (B) Comparison between the protein sequences of KIF3C and mouse brain KIF3A and KIF3B (diagonal dot matrix plot at a window of size 8 and stringency of 60%). The highest divergence resides in the last 79 amino acids of KIF3C (not included in the plots). A similar comparison between KIF3A (Aizawa et al., 1992) and KIF3B (Yamazaki et al., 1995) is also shown. Note that KIF3C is more similar to KIF3B (middle plot) than it is to KIF3A (left plot) or KIF3A is to KIF3B (right plot). (C) Diagram showing the probability of forming a coiled-coil calculated for KIF3C according to Lupas et al. (1991), using a window of 21 amino acids. (D) Sequence charge analysis of KIF3C, KIF3A, and KIF3B in a restricted domain (underlined in C) from the expected region of dimerization. Charge distribution in KIF3C indicates a low probability of either homodimerization or heterodimerization with KIF3B, but a high probability of dimerization with KIF3A.

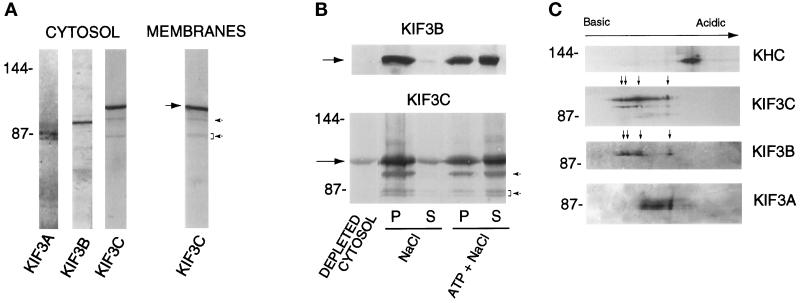

We have raised an antibody against a polypeptide containing amino acids 363–576 of KIF3C. In Western blots of rat brain homogenate, cytosol, and a crude membrane fraction, the affinity-purified antibody detected a major band of approximately 100 kDa as well as three minor bands that migrated at positions close to KIF3A and KIF3B (Figure 2A). These faint bands were not stained by antibodies to KIF3B (see Figure 3A) or KIF3A (see Figure 3B), nor did anti-KIF3C antibodies stain the bona fide KIF3A polypeptides (see Figure 3B). These results definitely rule out a possible cross-reactivity of the anti-KIF3C antibody with KIF3A and KIF3B. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that these minor polypeptides that cross-react with the KIF3C antibody are proteolytic fragments of KIF3C, they may be additional members of the KIF3 family of kinesins (see below).

Figure 2.

Characterization of KIF3C protein. (A) KIF3C is both present in cytosol and associated with membranes. A 120,000 × g supernatant (cytosol) and membrane fraction were prepared from rat brain postnuclear supernatant. Samples of equal protein concentration were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies to KIF3A, KIF3B, and KIF3C. The large arrow points to KIF3C. Note that, similar to mouse KIF3A (Kondo et al., 1994), rat KIF3A is detected as a doublet in cytosol. (B) Nucleotide-dependent microtubule binding and release of cytosolic KIF3C protein. Rat brain cytosol was incubated with microtubules in the presence of 5 mM AMP-PNP. The mixture was separated by centrifugation into a supernatant (depleted cytosol) and a microtubule pellet. Microtubules were extracted with either 100 mM NaCl or 100 mM NaCl plus 7.5 mM ATP. Supernatants (S) and pellets of the extracted microtubules (P) were obtained by centrifugation. Equivalent volumes from each fraction were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-KIF3C and anti-KIF3B antibodies. Note that both KIF3C and KIF3B (arrows) are released by ATP and salt. Much less KIF3C and KIF3B are released by salt alone. (C) Isoelectric forms of KIF3C. A microtubule motor protein-enriched fraction obtained from rat brain cytosol was analyzed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and Western blotting. Note the high number of charge variants of KIF3C compared with the other motor molecules tested (KHC, kinesin heavy chain). Arrows show the major charge isoforms in KIF3C and KIF3B. The positions of molecular size markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated at left. Note that the affinity-purified anti-KIF3C antibody also detects three minor polypeptides (arrowheads in A), which show nucleotide-dependent binding to and release from microtubules similar to KIF3C (arrowheads in B).

Figure 3.

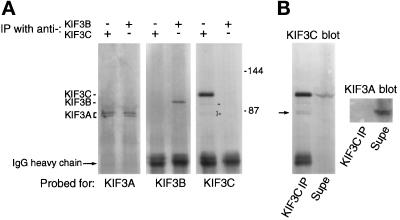

(A). Coimmunoprecipitation of KIF3A but not KIF3B with anti-KIF3C antibodies. KIF3C and KIF3B were immunoprecipitated from two identical samples of rat brain cytosol with affinity-purified antibodies. The immunoprecipitated material was analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of KIF3 family members. KIF3A was detected in both immunoprecipitates, but KIF3B and KIF3C did not coimmunoprecipitate with each other. Note that the anti-KIF3C antibody does not cross-react with KIF3B or KIF3A as seen in the sample immunoprecipitated with anti-KIF3B antibody (lane 6 from the left), but does detect, faintly, three additional polypeptides only in the sample immunoprecipitated with anti-KIF3C antibody (lane 5, arrowheads). The positions of molecular size markers (in kilodaltons) is indicated at right. (B) Immunoprecipitation after dissociation of the KIF3C/3A complex by SDS shows absence of cross-reactivity of anti-KIF3C antibody with KIF3A. Before immunoprecipitation with antibody to KIF3C, the sample was solubilized and boiled in SDS and then diluted in Triton X-100– containing buffer. Note that all KIF3A remained in the supernatant (supe, KIF3A blot) and was not detected in the KIF3C blot. However, the anti-KIF3C antibody detects a protein doublet of electrophoretic mobility similar to KIF3A in the immunoprecipitated material (KIF3C blot, arrow).

In the presence of AMP-PNP, cytosolic KIF3C bound to microtubules, from which it was released by ATP and salt. Much less KIF3C was released by salt alone (Figure 2B). This result suggests that native KIF3C has kinesin-like, nucleotide-dependent microtubule-binding activity. The three minor polypeptides recognized by the anti-KIF3C antibody also bound to and were released from microtubules in a nucleotide-dependent manner (Figure 2B).

Analysis by two-dimensional electrophoresis (O’Farrell, 1975) of a motor protein-enriched fraction obtained from rat brain cytosol indicated that KIF3C is composed of multiple isoelectric forms (Figure 2C), possibly due to different phosphorylation states. Compared with kinesin heavy chain as well as with the other members of the KIF3 family of kinesins, KIF3C is the most heterogeneous with respect to charge variants. The number and distribution of the major charge isoforms of KIF3C were strikingly similar to those of KIF3B (arrows in Figure 2C), suggesting similarities in posttranslational modification of these two related motors.

KIF3C Forms a Complex with KIF3A in Vivo

The similarity of KIF3C to KIF3B in the distribution of charges (Figure 1D) in the putative dimerization region suggested that KIF3C, like KIF3B, might be present in brain as a heterodimer with KIF3A. To test this hypothesis, we immunoprecipitated KIF3C and KIF3B from separate samples of rat brain cytosol by using highly specific, affinity-purified antibodies raised against fusion proteins to each of these KRPs. As shown in Figure 3A, KIF3B was only immunoprecipitated by the anti-KIF3B antibody. Similarly, KIF3C was only immunoprecipitated by the anti-KIF3C antibody. However, KIF3A was detected in both immunoprecipitates. These results suggest that KIF3A is present in two distinct complexes: one with KIF3B, and a second with KIF3C. Furthermore, KIF3B and KIF3C are not present in a complex. The immunoprecipitation experiments do not prove a direct interaction between KIF3C and KIF3A. However, based on the similarities between KIF3C and KIF3B, it is likely that KIF3C interacts directly with KIF3A via the coiled-coil region, analogous to KIF3B (reviewed in Scholey, 1996).

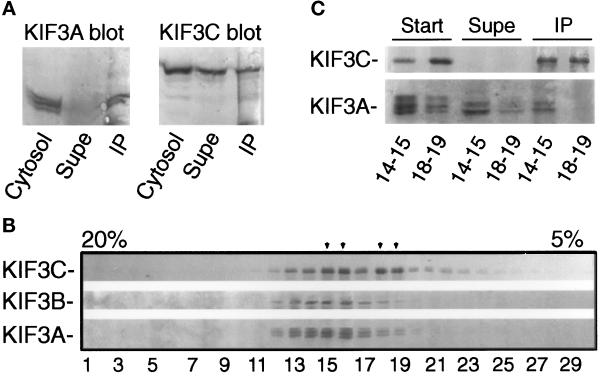

To test whether there is any KIF3C that is not associated with KIF3A, we immunoprecipitated all KIF3A from rat brain cytosol and analyzed the depleted cytosol and precipitated material for the presence of KIF3C. Only a fraction of KIF3C was coimmunoprecipitated with KIF3A (Figure 4A). This suggests that KIF3C is present in at least two distinct forms in cytosol. To test further this possibility, a rat brain cytosolic fraction enriched in microtubule motors was fractionated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. It was apparent that, unlike KIF3A and KIF3B, KIF3C sediments at two densities in the sucrose density gradient (Figure 4B), consistent with the idea that KIF3C is part of two complexes that differ either in their composition or conformation. One of these complexes sediments similarly to KIF3B. Since KIF3C and KIF3B are comparable in size, this result may suggest that this fraction of KIF3C forms a complex similar to that of KIF3B. Taken together with the immunoprecipitation experiments (Figure 3A), it is likely that this complex also contains KIF3A. The more slowly sedimenting KIF3C complex does not copeak with KIF3A and may not contain KIF3A. To test this hypothesis, we have immunoprecipitated KIF3C from the two peak fractions of the sucrose density gradient and analyzed the immunoprecipitated material for the presence of KIF3A. As expected, KIF3A was coimmunoprecipitated with KIF3C only from the lower fractions (Figure 4C), confirming that only the faster sedimenting KIF3C complex contains KIF3A. Analysis of the tissue distribution of the three members of the KIF3 family, as detailed below, also supports the idea that some of KIF3C is not associated with KIF3A.

Figure 4.

KIF3C is present in two different complexes in vivo. (A) All of KIF3A, but only a fraction of KIF3C, from cytosol is coimmunoprecipitated with anti-KIF3A antibodies. Starting material (cytosol), depleted cytosol (supe), and anti-KIF3A–immunoprecipitated material (IP) were probed for the presence of KIF3A and KIF3C. (B) KIF3C does not cosediment with KIF3B in sucrose density gradients. A rat brain cytosolic fraction enriched in microtubule motors (see MATERIALS AND METHODS) was centrifuged over a 5–20% sucrose-density gradient for 15 h at 120,000 × g. Fractions were collected from the bottom of the tube (left side of the blot) and analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of KIF3 motors. Note that KIF3C has a different sedimentation profile than KIF3A and KIF3B. KIF3C peaks at two separate densities of the gradient (arrowheads), suggesting that it is present in two different complexes or forms. Under these conditions, kinesin heavy chain peaks in fractions 13 and 14. (C) The slowly sedimenting KIF3C is not associated with KIF3A. KIF3C was immunoprecipitated from fractions 14–15 and 18–19 (see B) with anti-KIF3C antibodies, and equivalent volumes from the starting material (start), depleted sample (supe), and immunoprecipitated material (IP) were analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of KIF3C and KIF3A. Note that KIF3A was coimmunoprecipitated only from fraction 14–15.

Tissue Distribution and Subcellular Localization of KIF3C

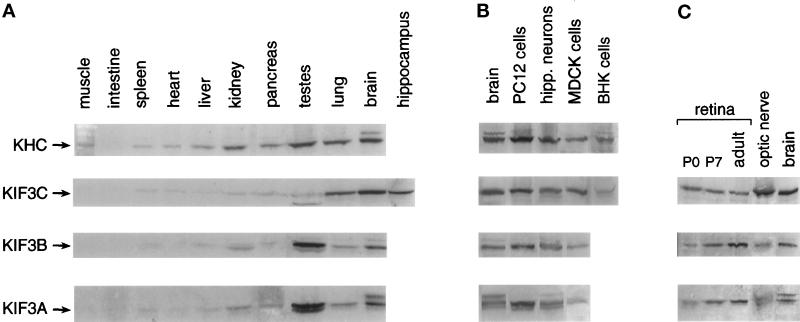

We have investigated the expression of KIF3C protein in tissues of the adult rat. The highest level of KIF3C was detected in brain, followed by retina and lung (Figure 5, A and C). Lower levels of the protein were found in the testes, pancreas, and kidney, and only trace amounts were found in the other tissues investigated. The hippocampus contained amounts of KIF3C similar to those in whole brain. The distribution of KIF3C differed from that of KIF3A and KIF3B only by its relatively low expression in the testes (Figure 5A) and high expression in the optic nerve (Figure 5C). In the testes, however, the anti-KIF3C antibody detected in Western blots an additional protein band of higher electrophoretic mobility than the bona fide KIF3C protein; this may represent a homologue or an alternatively spliced isoform of KIF3C.

Figure 5.

Detection of KIF3C in rat tissues and cultured cells. Samples of equal protein content from several adult (panel A and right lanes in panel C) and neonatal (left lanes in C) rat tissue extracts and from cells in culture (B) were probed by Western blotting for the presence of kinesin motors. KIF3C is preferentially expressed in brain, retina, and lung (A and C), and its level is constant during postnatal development (C) (P0 and P7 indicate day 0 and 7 after birth). Note also the high level of expression of KIF3C but not KIF3A and KIF3B in MDCK cells (B) and optic nerve (C). Kinesin heavy chain (KHC) was detected with the SK-394 antibody.

The high level of expression of KIF3C in lung suggested that it may be present in cells of nonneuronal origin. We have tested for the presence of KIF3C in several cell lines, including fibroblasts and epithelial cells (Figure 5B). As expected, KIF3C was found at high levels in cultured hippocampal neurons and PC12 cells. A particularly high level of expression was also seen in MDCK cells, while smaller amounts were detected in BHK cells.

The expression of KIF3C during postnatal development was investigated in the retina. No significant differences were seen in the level of KIF3C throughout these stages of development (Figure 5C).

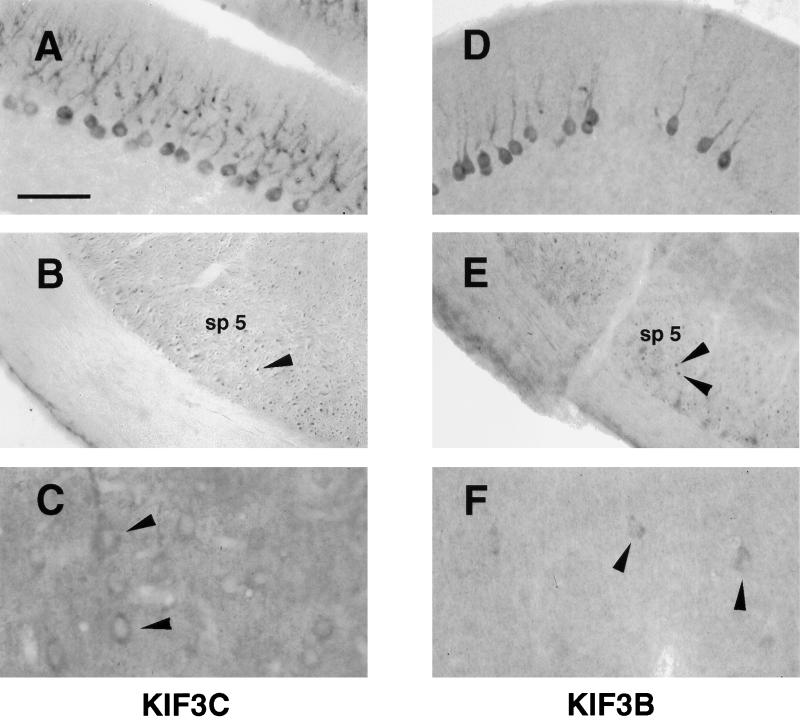

The localization of KIF3C protein was examined in transverse brain sections from adult rats (Figure 6). Anti-KIF3C antibodies labeled neuronal cells in the cerebellum, cerebral cortex, and the hippocampus. The labeling was particularly intense in Purkinje cells of the cerebellum (Figure 6A). Here, the staining was cytoplasmic and prominent throughout the Purkinje dendritic trees. In the hippocampus, the labeling appeared localized mainly to cell bodies of pyramidal cells. Although variable, some labeling of axon bundles in different regions of the cerebrum was also seen (Figure 6B). The overall distribution of KIF3C in the brain was mostly similar to that of KIF3A (our unpublished results) and KIF3B (Figure 6, D–F), with a few important differences. For example, the anti-KIF3B antibody occasionally appeared to stain subsets of cerebellar Purkinje cells (Figure 6D). Also, the staining for KIF3A and KIF3B was less intense than for KIF3C, but this could be due to differences in reactivity of the antibodies.

Figure 6.

Immunolocalization of KIF3C and KIF3B in rat brain. Labeling of KIF3C (A–C) and KIF3B (D–F) in cryosections from adult rat brain. KIF3C is highly expressed in the cell bodies and dendritic trees of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum (A). KIF3B, but not KIF3C, occasionally stains subsets of Purkinje cells (compare D with A). Bundles of axons immunoreactive for KIF3C (B) and KIF3B (E) are seen cut in cross-section (arrowheads) in the spinal trigeminal tract (sp 5). In the cerebral cortex, KIF3C stains many neurons (C), whereas KIF3B immunoreactivity is weaker (F). Affinity-purified antibodies were diluted 1:500 (A and B) or 1:50 (C–F). Labeling was absent when an immune IgG fraction depleted of the anti-KIF3C antibody by adsorption against the antigen was used instead of the affinity-purified anti-KIF3C antibody (our unpublished results). Bar, 100 μm (A, B, D, and E) and 50 μm (C and F).

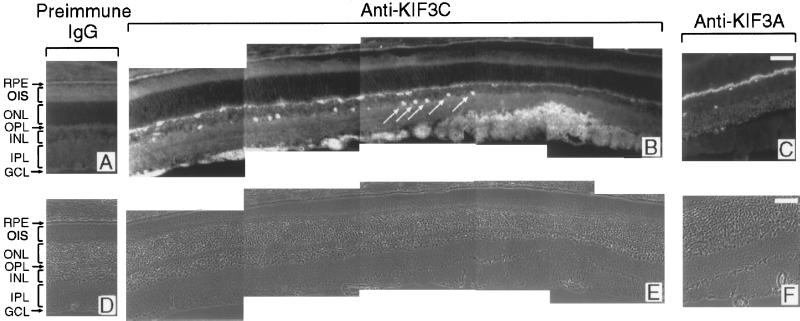

In the retina, KIF3C immunoreactivity was detected primarily in the optic nerve fiber layer (Figure 7B). In addition, the most proximal row of perikarya in the inner nuclear layer was brightly labeled by the antibody. From their position and distribution, these neurons are likely to be amacrine cells. Labeling was also seen in the outer plexiform layer (Figure 7B), which contains the synapses between the photoreceptors and horizontal and bipolar neurons. In contrast to what was found in the brain sections, there was no clear overlap between the labeling patterns obtained with anti-KIF3C (Figure 7B), anti-KIF3A (Figure 7C), and anti-KIF3B (our unpublished results) antibodies in the retina. This suggests that KIF3C may be present in retinal cells that express little if any KIF3A or KIF3B. In support of this conclusion, KIF3C, but not KIF3A or KIF3B, was enriched in the optic nerve, which is formed from the axons of the retinal ganglion cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 7.

Immunolocalization of KIF3C (B) and KIF3A (C) in the adult retina, showing their distinct distribution. KIF3C is detected primarily in the ganglion cell and optic nerve fiber layer and in a subpopulation of neurons in the inner nuclear layer (arrows in B). Labeling is also present in the outer plexiform layer. By contrast, KIF3A is detected only in the outer and inner plexiform layers (C). (A) Background labeling of the retina when preimmune IgG was used instead of the anti-KIF3C antibody. (D, E, and F) Corresponding phase-contrast micrographs. RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; OIS, outer and inner segments of photoreceptor cells; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell and optic nerve fiber layers. Bars, 50 μm.

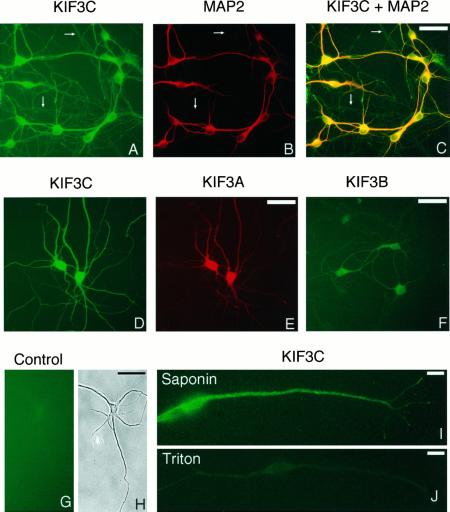

To investigate further the subcellular localization of KIF3C, we have studied its distribution in cultured hippocampal neurons. The anti-KIF3C antibody stained the cell bodies intensely and, to a somewhat lesser extent, both MAP2-positive (Figure 8A-C) and Tau-positive (our unpublished results) processes of neurons, indicating the presence of this motor molecule in both dendrites and axons, respectively. The level of KIF3C appeared to be higher in dendrites than in axons. The labeling was mostly diffuse throughout the cell but occasionally revealed fine punctate structures, especially when cells were permeabilized with saponin before fixation (Figure 8I). Since most of this punctate labeling was sensitive to extraction with Triton X-100 (Figure 8J), these structures possibly corresponded to small cargo vesicles (see below). A residual labeling with anti-KIF3C antibody was seen in Triton X-100 extracted specimens (Figure 8J) and may correspond to cytoskeleton-bound motor. KIF3B was localized mainly to cell bodies, and only weakly to the processes (Figure 8F), as reported previously (Yamazaki et al., 1995). The distribution of KIF3A resembled that of KIF3C, although the labeling of the cell processes was, by comparison, less intense. Glial cells detected occasionally on the coverslip were also stained with the anti-KIF3C antibody, although less intensely than neurons.

Figure 8.

Immunocytochemistry of cultured hippocampal neurons. Formaldehyde-fixed and permeabilized cells (A–H) and cells fixed in methanol (I and J) after extraction with either saponin (I) or Triton X-100 (J) were stained with antibodies to KIF3B (F) or KIF3C (I and J), or double stained with anti-KIF3C (A and D) and either anti-MAP2 (dendritic marker) (B) or anti-KIF3A (E) antibodies. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary antibodies were used to detect KIF3C or KIF3B (green). Antibodies to MAP2 and KIF3A were detected with rhodamine-labeled secondary antibodies (red). The image shown in panel C was obtained by simultaneous visualization of both fluorophores through a broad-band filter. KIF3C is diffusely distributed to cell bodies, as well as to dendrites (stained in yellow-orange in C) and axons (stained in green in C), with occasional localization to fine punctate structures (I). Arrows in panels A–C point to some axonal processes, which are not stained with the anti-MAP2 antibody. Note that KIF3C staining is largely removed by preextraction of the cells with Triton X-100 (J). Also note that, compared with KIF3C (D) and KIF3A (E), KIF3B is detected in lower amounts in processes (F). An IgG fraction depleted of the anti-KIF3C antibody produced only background staining (G). (H) Phase-contrast micrograph corresponding to panel G. Micrographs shown in panels A–C and panels D and E are from double-labeling experiments. Bars, 50 μm (A–H) and 10 μm (I and J).

KIF3C Is Associated with Membrane-bound Vesicles

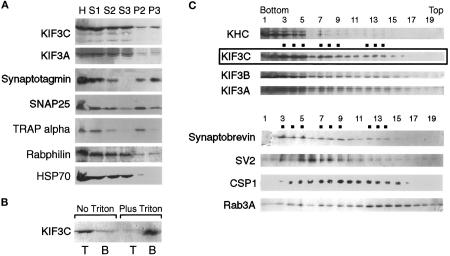

The data presented so far suggested that KIF3C is both soluble and membrane-associated. To determine the proportion that is membrane-associated, we used differential centrifugation to fractionate a brain postnuclear supernatant. KIF3C was present in both the medium-speed pellet P2 (containing unbroken synaptosomes and heavy membranes) and the high-speed pellet P3 (Figure 9A). Since only a relatively small fraction of KIF3C appeared to cosediment with membranes, we have asked whether this truly represents membrane-associated motor or cytosolic motor present as an impurity in the pellet. First, we have analyzed in the same fractions the distribution of HSP70, a cytosolic protein (Pelham, 1988), and of rabphilin, a protein that is both cytosolic and membrane bound (Li et al., 1994). A higher proportion of KIF3C was detected in the membrane-containing pellets than either HSP70 or rabphilin (Figure 9A). Second, we have separated pelleted rat brain membranes from residual, soluble proteins by flotation on sucrose gradients. As shown in Figure 9B (left lanes), most of KIF3C was recovered in the upper fraction. When the pellet was extracted with Triton X-100 before flotation, essentially all KIF3C remained in the bottom fraction (Figure 9B, right lanes), suggesting that it was indeed associated with detergent-soluble membranes.

Figure 9.

Association of KIF3C with vesicle membranes. (A) Subcellular fractionation of rat brain homogenate by differential centrifugation. The homogenate (H), postnuclear supernatant (S1), 14,000 × g supernatant (S2) and pellet (P2), and 120,000 × g supernatant (S3) and pellet (P3) were probed for KIF3C, KIF3A, HSP70, and markers for various membrane compartments. Note that most of the membrane-associated KIF3C is found, together with the synaptic vesicle marker synaptotagmin, in the high-speed pellet (P3); a lower amount cofractionates with the medium-speed pellet (P2), enriched in endoplasmic reticulum (TRAP α) and synaptosomal plasma membrane (SNAP25). Also note that the cytosolic marker HSP70 is essentially absent from the P3 fraction. (B) Vesicle-bound KIF3C is solubilized by Triton X-100 extraction. Pelleted brain membranes were resuspended in buffer without or with Triton X-100 and separated by flotation from residual cytosolic proteins (left lanes) or detergent-solubilized proteins (right lanes). T and B are top (membrane) and bottom fractions after flotation. (C) Cofractionation of KIF3C with rat brain vesicles. A crude membrane fraction depleted of heavy membranes (see MATERIALS AND METHODS) was fractionated by flotation through a Nycodenz gradient. Samples from each fraction were analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of motor molecules and various vesicle markers. The broad distribution of the markers is typical for this type of vesicle fractionation. Note that the distribution of KIF3C partially overlaps with that of several synaptic vesicle membrane proteins, but most resembles that of synaptobrevin. Dots indicate peaks in the distribution of KIF3C and synaptobrevin. KHC, kinesin heavy chain.

To investigate whether KIF3C is associated with a particular vesicle population, we subjected the high-speed pellet to separation by flotation through a Nycodenz density gradient and compared the distribution of KIF3C with that of various vesicle membrane markers. This membrane fraction was devoid of unbroken synaptosomes and heavy membrane compartments (which were pelleted in the medium-speed centrifugation step) and would be expected to include vesicles in transit through neuronal processes as well as synaptic vesicles from broken synaptosomes. As shown in Figure 9C, KIF3C was recovered in three overlapping peaks. KIF3A and KIF3B showed slightly broader, but overall similar distribution to KIF3C and to each other in the Nycodenz gradient. Kinesin heavy chain was restricted to the denser fractions. Several membrane-associated proteins known to be transported within axons were contained in the KIF3C-positive fractions, but their distribution only partially overlapped that of KIF3C. The closest overlap was between KIF3C and synaptobrevin. These data suggest that KIF3C may serve as a motor for a yet uncharacterized vesicle population that includes vesicles carrying synaptobrevin.

DISCUSSION

This paper reports the identification and cloning of a novel member of the KIF3 family of kinesins, KIF3C, which is expressed primarily in brain and nerves but is also present in significant amounts in certain tissues and cells of nonneuronal origin. Its distribution is similar to that of KIF3A and KIF3B in most of the brain, but differs in the retina. Like KIF3B, KIF3C associates with KIF3A. Unlike KIF3B, a significant fraction of KIF3C is not in association with KIF3A, suggesting that KIF3C is part of two different motor complexes. These findings imply that KIF3 motors may play a more complex and extensive role in neuronal membrane trafficking than previously thought (Kondo et al., 1994; Yamazaki et al., 1995; Hirokawa, 1996). Consistent with this idea, we find that: 1) the KIF3C and KIF3B polypepeptides exhibit an unusually large number of isoelectric forms that could reflect posttranslational modifications or additional isoforms; and 2) affinity-purified antibodies against KIF3C recognize additional kinesin-like polypeptides in the size range of the known KIF3 motors. These findings suggest that additional members of the KIF3 family are likely to be expressed in neurons.

An Additional Member of the KIF3 Group of Kinesin Motors

The KIF3 family of kinesins includes pairs of interacting polypeptides identified in Drosophila melanogaster (KLP64D and KLP68D) (Pesavento et al., 1994), mouse (KIF3A and KIF3B) (Kondo et al., 1994; Yamazaki et al., 1995), and sea urchin (SpKRP85 and SpKRP95) (Cole et al., 1992, 1993; Rashid et al., 1995). In addition, the protein products of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Fla10 gene (Walther et al., 1994) and the Caenorhabditis elegans Osm3 gene (Shakir et al., 1993; Tabish et al., 1995) belong to this family. KIF3A and SpKRP85, on the one hand, and KIF3B and SpKRP95, on the other hand, share similar biochemical and functional properties (Scholey, 1996). In mouse and sea urchin, these pairs of KIF3 members form heterodimers via coiled coils of similar size in their central domains (Rashid et al., 1995; Yamazaki et al., 1995); these dimers associate with a third polypeptide (KAP3) to form the heterotrimeric kinesin-like holoenzyme (Wedaman et al., 1996; Yamazaki et al., 1996). We also cloned KIF3A and KIF3B from rat, and our results show that these are part of a complex of similar size to the mouse KIF3A/KIF3B/KAP3 complex.

KIF3C is the third and largest member of the KIF3 family of kinesins. It shares higher sequence similarity with KIF3B than with KIF3A both in the α-helical coiled-coil region and in the globular tail domain (Figure 1B). The similarity between KIF3C and KIF3B extends also to the distribution in a pH gradient of the main charge isoforms of the two polypeptides. The highest divergence between KIF3C and KIF3B occurs in the 79-amino acid segment at the carboxy terminus of the molecule. The carboxy terminus of KIF3C contains a proline-rich domain. Since such domains have been implicated in protein–protein interactions (Ren et al., 1993; Linial, 1994), this region of KIF3C may participate in binding of a putative accessory subunit of the KIF3C complex, or of a cargo-associated receptor. The larger size of KIF3C compared with its relatives is primarily due to a 26-amino acid glycine-rich region within the motor domain (amino acid residues 260–285), which is absent in both KIF3A and KIF3B (Figure 1, A and B; see also Aizawa et al., 1992; Yamazaki et al., 1995). By comparison of the KIF3C motor domain with that of human conventional kinesin, the glycine-rich insert would be situated in loop 11 of the crystal structure of the kinesin motor domain (Kull et al., 1996). It is believed that this loop is part of the “switch II” region that undergoes conformational change during the mechanochemical cycle of kinesin (Sablin et al., 1996; Vale, 1996).

Secondary structure predictions suggest that KIF3C might form dimers with a suitable partner through a coiled-coil interaction of the stalk domain similar to that found in the KIF3A/3B dimer. In accordance with the distribution of charges in a region proposed to be critical for dimerization (Rashid et al., 1995), we have found that KIF3C forms a complex with KIF3A, but not with KIF3B. It remains to be established whether the KIF3C/3A complex identified in this study contains associated polypeptides similar to KAP3 from mouse.

We have shown that cytosolic KIF3C binds to microtubules in a nucleotide-dependent manner characteristic of kinesins. Since we were not able to express in soluble form either the full-length protein or its motor domain, we could not directly demonstrate the motor activity and directionality of movement of KIF3C. However, based on its precise structural resemblance with KIF3A and KIF3B, it is likely that KIF3C is a plus-end directed motor itself.

A Novel Vesicle-associated Motor

Similar to conventional kinesin (Vale et al., 1985a; Hollenbeck, 1989; Schnapp et al., 1992) and to the other members of the KIF3 family of motors (Yamazaki et al., 1995), KIF3C is present in both soluble and membrane-bound pools. About 30% of KIF3C was recovered in heavy and light membrane fractions, both in isotonic (K-HEPES) and hypotonic (BRB80) buffers, and most of this KIF3C copurified with the membranes upon flotation, suggesting a stable interaction of this motor with membranous particles.

It is assumed that the numerous neuronal kinesins are responsible for the long-range intracellular transport and sorting of organelles to different targets within axons and dendrites (Coy and Howard, 1994; Hirokawa, 1996). The current view is that the different KRPs interact via specific receptors with different populations of vesicles. In very few cases, however, have the cargoes been clearly identified. Genetic and biochemical evidence indicate that the unc104 protein in C. elegans (Hall and Hedgecock, 1991) and its mammalian homologue KIF1A (Okada et al., 1995) transport synaptic vesicle precursors to the axon terminal. Mouse KIF1B (Nangaku et al., 1994) and the D. melanogaster KLP67A (Pereira et al., 1997) appear to transport mitochondria. The cargoes for the other neuronal kinesins, including the KIF3A/3B complex, are not known (Sekine et al., 1994; Noda et al., 1995; Yamazaki et al., 1995). In the case of mouse KIF3A and KIF3B, data are consistent with a role in the fast axonal transport of a population of vesicles that differ from synaptic vesicle precursors (Yamazaki et al., 1995). KIF3A accumulates with anterogradely moving organelles after ligation of peripheral nerves, and antibodies to KIF3A and KIF3B reveal a punctate labeling pattern in neuronal cell bodies and processes (Kondo et al., 1994; Yamazaki et al., 1996). An antibody to KIF3B immunoprecipitates some uncharacterized vesicles (Yamazaki et al., 1995).

In the brain, KIF3C is localized to most neurons, as are KIF3A, KIF3B, and conventional kinesin (our unpublished results). The presence of KIF3C was especially prominent to large neurons, where it appears concentrated in cell bodies and dendrites. Generally, axonal staining in brain sections was less frequently seen, but this could be due to their smaller size compared with cell bodies and dendrites. In hippocampal neurons in culture, KIF3C was clearly detected in axons, although at lower levels than in the cell bodies and dendrites. Biochemical and morphological data indicate that KIF3C was also concentrated in the axons of retinal ganglion cells.

Interestingly, in the retina, KIF3C was present at locations that showed little or no immunoreactivity toward KIF3A or KIF3B. Although this result may be explained by differences in the sensitivity of antibodies used in immunocytochemistry, it raises the intriguing possibility that KIF3C may have functions independent of its association with KIF3A. Such an interpretation is supported by the biochemical data showing that KIF3C exists in two forms, only one of which contains KIF3A.

Several observations are consistent with a role of KIF3C in intracellular vesicular transport. First, in spite of its mostly diffuse distribution (which could be due to the high level of soluble motor), occasionally punctate labeling patterns could be detected by immunocytochemistry, suggesting an association with small vesicles. Second, the distributions of KIF3C and synaptobrevin overlap in a membrane fraction that was separated by flotation through a Nycodenz density gradient. Synaptobrevin and its homologues are thought to be on vesicles destined for membrane fusion (Sollner et al., 1993; Pfeffer, 1996), and some of these could be transported by a KIF3C motor. Although the overlap between KIF3C and synaptobrevin was less obvious by immunocytochemistry (our unpublished results), this could be in part explained by the presence of a large soluble pool of KIF3C, which could mask the distribution of membrane-associated KIF3C. Third, the high concentration of KIF3C in the optic nerve is consistent with a role in fast axonal transport.

In addition to its high level of expression in brain, retina, and optic nerve, KIF3C was biochemically detected in significant amounts in kidney, pancreas, and especially lung. Epithelial cells grown in culture, such as MDCK cells, also contained relatively high levels of KIF3C, which were comparable to those in cultured hippocampal neurons. It is known that vesicular transport pathways in epithelial cells utilize microtubule motors to selectively deliver lipid and protein components to different regions (i.e., apical and basolateral) of the polarized plasmamembrane (reviewed in Lafont and Simons, 1996). The fact that components of the SNARE machinery similar to those characterized in neurons are present in MDCK cells (Low et al., 1996) suggests that motors similar to neuronal kinesins could participate in intracellular membrane trafficking, sorting, and targeting in epithelial cells.

Multiple Complexes of a Kinesin-related Polypeptide

In mouse and sea urchin, the KIF3A/3B holoenzyme is a heterotrimer of two motor subunits and a nonmotor polypeptide, which fractionates as a single peak by sucrose density centrifugation and gel filtration (Cole and Scholey, 1995; Yamazaki et al., 1995). Unlike KIF3A or KIF3B, KIF3C sediments in sucrose density gradients at two distinct densities, suggesting that it may be part of two different complexes. One of these copeaks with KIF3A and KIF3B; the other has a smaller sedimentation coefficient. It is possible that the two peaks may correspond to different conformations of the same complex; this has been shown for conventional kinesin and the sea urchin KIF3 complex, both of which undergo ionic-strength–dependent conformational changes that change their sedimentation properties (Hackney et al., 1992; Wedaman et al., 1996). Since our experiments were performed in conditions of low ionic strength (in which both conventional kinesin and KIF3A/3B sedimented as single peaks), it is unlikely that the KIF3C peak, which we observe at lower density, is the result of such a salt-induced conformational change of the molecule. It is possible that the slower sedimenting complex lacks a putative accessory subunit or that it contains a smaller accessory subunit. It is more likely that this form of KIF3C may not be associated with the KIF3A subunit, as is suggested by the sedimentation pattern of KIF3A, which does not show a corresponding second peak, and by experiments of coimmunoprecipitation from the two KIF3C peak fractions of the sucrose density gradient (see Figure 4). If so, this would be evidence that some of the native KIF3C may exist and function independently of KIF3A. Future work will be required to investigate the composition of these complexes, what regulates their formation, and what is the functional relationship between them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Lawrence S. B. Goldstein for making us aware of the KIF3A/KIF3C interaction and communicating results before publication. We also thank Dr. Elio Raviola for helpful discussions on retinal localization of KIF3 motors, and Dr. Jim Deshler, Dr. Martin Highett, and Dr. Eric Arn for comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to Dr. Kathleen Buckley, Dr. Robert Burgoyne, Dr. Pietro De Camilli, Dr. Reinhard Jahn, Dr. Kenneth Kosik, Dr. Timothy Mitchison, Dr. Tom Rapoport, and Dr. Jonathan Scholey for their generous gifts of antibodies. We are especially grateful to Dr. Kimberly Goslin, Dr. Zoia Muresan, and Dr. Gordon Ruthel for providing the cultures of hippocampal neurons and MDCK cells. We also thank Dr. Connie Cepko for the P0 and P7 retinal samples. Taxol was a gift from the National Cancer Institute. This work was supported by grants to Bruce J. Schnapp from the National Institutes of Health (NS-26846) and the Council for Tobacco Research (no. 3802R1). Part of Nancy Chamberlin’s work was supported by a grant from the Massachusetts Thoracic Society and the American Lung Associations of Massachusetts. Virgil Muresan was supported by a Neuromuscular Disease Research Fellowship from the Muscular Dystrophy Association during the initial part of this study.

REFERENCES

- Aizawa H, Sekine Y, Takemura R, Zhang Z, Nangaku M, Hirokawa N. Kinesin family in murine central nervous system. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1287–1296. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas PW, Deitch JS, Black MM, Banker GJ. Polarity orientation of microtubules in hippocampal neurons: uniformity in the axon and nonuniformity in the dendrite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8335–8339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel LK, Raymond PA. Improved method for obtaining 3-μm cryosections for immunocytochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:1383–1388. doi: 10.1177/38.9.2201738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert M, Maycox PR, Navone F, De Camilli P, Jahn R. Synaptobrevin: an integral membrane protein of 18,000 daltons present in small synaptic vesicles of rat brain. EMBO J. 1989;8:379–84. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M, Reed R. Correspondence between a mammalian spliceosome component and an essential yeast splicing factor. Science. 1993;262:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.8211113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom GS, Wagner MC, Pfister KK, Brady ST. Native structure and physical properties of bovine brain kinesin and identification of the ATP binding subunit polypeptide. Biochemistry. 1988;27:3409–3416. doi: 10.1021/bi00409a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady ST. Molecular motors in the nervous system. Neuron. 1991;7:521–533. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley K, Kelly RB. Identification of a transmembrane glycoprotein specific for secretory vesicles of neural and endocrine cells. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1284–1294. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.4.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain LH, Burgoyne RD. Identification of a novel cysteine string protein variant and expression of cysteine string proteins in non-neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7320–7323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DG, Cande WZ, Baskin RJ, Skoufias DA, Hogan CJ, Scholey JM. Isolation of sea urchin egg kinesin-related protein using peptide antibodies. J Cell Sci. 1992;101:291–301. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DG, Chinn SW, Wedaman KP, Hall K, Vuong T, Scholey JM. Nature. 1993;366:268–270. doi: 10.1038/366268a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DG, Scholey JM. Purification of kinesin-related protein complexes from eggs and embryos. Biophys J. 1995;68:158s–162s. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coy DL, Howard J. Organelle transport and sorting in axons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:662–667. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elluru RG, Bloom GS, Brady ST. Fast axonal transport of kinesin in the rat visual system: functionality of kinesin heavy chain isoforms. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:21–40. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway PG, Perry G, Kosik KS, Gambetti P. Hirano bodies contain tau protein. Brain Res. 1987;403:337–3340. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslin K, Schreyer DJ, Skene JH, Banker G. Development of neuronal polarity: GAP-43 distinguishes axonal from dendritic growth cones. Nature. 1988;336:672–674. doi: 10.1038/336672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackney DD, Levitt JD, Suhan J. Kinesin undergoes a 9 S to 6 S conformational transition. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8696–8701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DH, Hedgecock EM. Kinesin-related gene unc104 is required for axonal transport of synaptic vesicles in C. elegans. Cell. 1991;65:837–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90391-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon DW, Yang Z, Goldstein LSB. Characterization of KIFC2, a neuronal kinesin superfamily member in mouse. Neuron. 1997;18:439–451. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann E, Gorlich D, Kostka S, Otto A, Kraft R, Knespel S, Burger E, Rapoport TA, Prehn S. A tetrameric complex of membrane proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:375–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidemann SR, Landers JM, Hamborg MA. Polarity orientation of axonal microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:661–5. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson JH, Cole DG, Terasaki M, Rashid D, Scholey JM. Immunolocalization of the heterotrimeric kinesin-related protein KRP(85/95) in the mitotic apparatus of sea urchin embryos. Dev Biol. 1995;171:182–194. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N. Molecular architecture and dynamics of the neuronal cytoskeleton. In: Burgoyne R, editor. The Neuronal Cytoskeleton. New York, Chichester, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1991. pp. 5–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N. Organelle transport along microtubules - the role of KIFs. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:135–141. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)10003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N, Pfister KK, Yorifuji H, Wagner MC, Brady ST, Bloom GS. Submolecular domains of bovine kinesin identified by electron microscopy and monoclonal antibody decoration. Cell. 1989;56:867–878. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90691-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbeck PJ. The distribution, abundance and subcellular localization of kinesin. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:2335–2342. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Sato-Yoshitake R, Noda Y, Aizawa H, Nakata T, Matsuura Y, Hirokawa N. KIF3A is a new microtubule-based anterograde motor in the nerve axon. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1095–1107. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.5.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosik KS, Duffy LK, Dowling MM, Abraham C, McCluskey A, Selkoe DJ. Microtubule-associated protein 2: monoclonal antibodies demonstrate the selective incorporation of certain epitopes into Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:7941–7945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.24.7941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kull FJ, Sablin EP, Lau R, Fletterick RJ, Vale RD. Crystal structure of the kinesin motor domain reveals a structural similarity to myosin. Nature. 1996;380:550–555. doi: 10.1038/380550a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov SA, Vaisberg EA, Shanina NA, Magretova NN, Chernyak VY, Gelfand VI. The quaternary structure of bovine brain kinesin. EMBO J. 1988;7:353–356. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey ML, Haimo LT. Cytoplasmic dynein binds to phospholipid vesicles. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1994;28:205–212. doi: 10.1002/cm.970280304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont F, Simons K. The role of microtubule-based motors in the exocytic transport of polarized cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1996;7:343–355. [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Takei K, Geppert M, Daniell L, Stenius K, Chapman ER, Jahn R, De Camilli P, Sudhof TC. Synaptic targeting of rabphilin-3A, a synaptic vesicle Ca2+/phospholipid-binding protein, depends on rab3A/3C. Neuron. 1994;13:885–898. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linial M. Proline clustering in proteins from synaptic vesicles. NeuroReport. 1994;5:2009–2015. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199410270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low S-H, Chapin SJ, Weimbs T, Komuves LG, Bennett MK, Mostov KE. Differential localization of syntaxin isoforms in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:2007–2018. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.12.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A, VanDyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RG, Ames BN. A method for determining the sedimentation behavior of enzymes: application to protein mixtures. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:1372–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteoli M, Takei K, Cameron R, Hurlbut P, Johnston PA, Jahn R, Sudhof TC, De Camilli P. Association of rab3A with synaptic vesicles at late stages of the secretory pathway. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:625–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muresan V, Godek CP, Reese TS, Schnapp BJ. Plus-end motors override minus-end motors during transport of squid axon vesicles on microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:383–397. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nangaku M, Sato-Yoshitake R, Okada Y, Noda Y, Takemura R, Yamazaki H, Hirokawa N. KIF1B, a novel microtubule plus end-directed monomeric motor protein for transport of mitochondria. Cell. 1994;79:1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niclas J, Navone F, Hom-Booher N, Vale RD. Cloning and localization of a conventional kinesin motor expressed exclusively in neurons. Neuron. 1994;12:1059–1072. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda Y, Sato-Yoshitake R, Kondo S, Nangaku M, Hirokawa N. KIF2 is a new microtubule-based anterograde motor that transports membranous organelles distinct from those carried by kinesin heavy chain or KIF3A/B. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:157–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell PH. High resolution two dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Yamazaki H, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Hirokawa N. The neuron-specific kinesin superfamily protein KIF1A is a unique monomeric motor for anterograde axonal transport of synaptic vesicle precursors. Cell. 1995;81:769–780. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschal BM, Vallee RB. Retrograde transport by the microtubule-associated protein MAP 1C. Nature. 1987;330:181–183. doi: 10.1038/330181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H. Heat-shock proteins. Coming in from the cold. Nature. 1988;332:776–777. doi: 10.1038/332776a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AJ, Dalby B, Stewart RJ, Doxsey SJ, Goldstein LSB. Mitochondrial association of a plus end-directed microtubule motor expressed during mitosis in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1081–1090. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesavento PA, Stewart RJ, Goldstein LSB. Characterization of the KLP68D kinesin-like protein in Drosophila: possible roles in axonal transport. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1041–1048. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.4.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer SR. Transport vesicle docking: SNAREs and associates. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:441–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid DJ, Wedaman KP, Scholey JM. Heterodimerization of the two motor subunits of the heterotrimeric kinesin, KRP85/95. J Mol Biol. 1995;252:157–162. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren R, Mayer BJ, Cicchetti P, Baltimore D. Identification of a ten-amino acid proline-rich SH3 binding site. Science. 1993;259:1157–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.8438166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov VI, Gyoeva FK, Gelfand VI. Kinesin is responsible for centrifugal movement of pigment granules in melanophores. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4956–4960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sablin EP, Kull FJ, Cooke R, Vale RD, Fletterick RJ. Crystal structure of the motor domain of the kinesin-related motor ncd. Nature. 1996;380:555–559. doi: 10.1038/380555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N, Okada Y, Noda Y, Kinoshita Y, Kondo S, Hirokawa N. KIFC2 is a novel neuron-specific C-terminal type kinesin superfamily motor for dendritic transport of multivesicular body-like organelles. Neuron. 1997;18:425–438. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawin KE, Mitchison TJ, Wordeman LG. Evidence for kinesin-related proteins in the mitotic apparatus using peptide antibodies. J Cell Sci. 1992;101:303–313. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnapp BJ. Retroactive motors. Neuron. 1997;18:523–526. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnapp BJ, Reese TS. Dynein is the motor for retrograde axonal transport of organelles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1548–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnapp BJ, Reese TS, Bechtold R. Kinesin is bound with high affinity to squid axon organelles that move to the plus-end of microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:389–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholey JM. Kinesin-II, a membrane traffic motor in axons, axonemes, and spindles. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1–4. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroer TA, Steuer ER, Sheetz MP. Cytoplasmic dynein is a minus end-directed motor for membranous organelles. Cell. 1989;56:937–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y, Okada Y, Noda Y, Kondo S, Aizawa H, Takemura R, Hirokawa N. A novel microtubule-based motor protein (KIF4) for organelle transports, whose expression is regulated developmentally. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:187–201. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakir MA, Fukushige T, Yasuda H, Miwi J, Siddiqui SS. C. elegans osm-3 gene mediating osmotic avoidance behavior encodes a kinesin-like protein. NeuroReport. 1993;4:891–894. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199307000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollner T, Bennett MK, Whiteheart SW, Scheller RH, Rothman JE. A protein assembly-disassembly pathway in vitro that may correspond to sequential steps of synaptic vesicle docking, activation and fusion. Cell. 1993;75:409–418. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RJ, Pesavento PA, Woerpel DN, Goldstein LSB. Identification and partial characterization of six members of the kinesin superfamily in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8470–8474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabish M, Siddiqui ZK, Nishikawa K, Siddiqui SS. Exclusive expression of C. elegans osm-3 kinesin gene in chemosensory neurons open to the external environment. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:377–389. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale RD. Switches, latches, and amplifiers: common themes of G proteins and molecular motors. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:291–302. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale RD, Reese TS, Sheetz MP. Identification of a novel force-generating protein, kinesin, involved in microtubule-based motility. Cell. 1985b;42:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale RD, Schnapp BJ, Reese TS, Sheetz MP. Organelle, bead, and microtubule translocations promoted by soluble factors from the squid giant axon. Cell. 1985a;40:559–569. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther Z, Vashishtha M, Hall JL. The Chlamydomonas FLA10 gene encodes a novel kinesin-homologous protein. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:175–188. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedaman KP, Meyer DW, Rashid DJ, Cole DG, Scholey JM. Sequence and submolecular localization of the 115-kD accessory subunit of the heterotrimeric kinesin-II (KRP85/95) complex. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:371–380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel D, Flugge UI. A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal Biochem. 1984;138:141–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Nakata T, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. KIF3A/B: A heterodimeric kinesin superfamily protein that works as a microtubule plus end-directed motor for membrane organelle transport. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1387–1399. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.6.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Nakata T, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. Cloning and characterization of KAP3: a novel kinesin superfamily-associated protein of KIF3A/3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8443–8448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Goldstein LSB. Characterization of the KIF3C neural kinesin-like motor from mouse. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:249–261. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]