Abstract

The current method for fabricating prosthetic sockets is to modify a positive mold to account for the non-homogeneity of the residual limb to tolerate load (i.e., rectified socket). We tested unrectified sockets by retaining the shape of the residual limb, except for a distal end pad, using an alginate gel process instead of casting. This investigation compared rectified and unrectified sockets. Forty-three adults with unilateral transtibial amputations were tested after randomly wearing both rectified and unrectified sockets for at least 4 weeks. Testing included a gait analysis, energy expenditure and Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire (PEQ). Results indicated no differences between sockets for gait speed and timing, gait kinematics and kinetics, and gait energy expenditure. There were also no differences in the Prosthetic Evaluation Questionnaire and 16 subjects selected the rectified socket, 25 selected the unrectified socket, and 2 subjects selected to use both sockets as their exit socket. Results seemed to indicate that more than one paradigm exists for shaping prosthetic sockets, and this paradigm may be helpful in understanding the mechanisms of socket fit. The alginate gel fabrication method was simpler than the traditional method. The method could be helpful in other countries where prosthetic care is lacking, may be helpful with new amputees, and may be helpful in typical clinics to reduce costs and free the prosthetist to focus more time on patient needs.

Keywords: Transtibial amputees, rectified and unrectified sockets, gait, energy expenditure, prosthetic evaluation questionnaire

Introduction

There are over 173,000 persons in the U.S. using a lower limb prosthesis, and between 85,000 to 114,000 new lower limb amputations each year.1,2,3 The prosthetic socket is the most important part of the prosthesis for these amputees.4 If the socket fits well, the individual's ability to function is much like a person with an able body. If the socket fits poorly, the results are chafing, bleeding, bruising, pressure sores and pain. These problems can reduce the amputee's functional ability, compromise their long term health, decrease independence, and increase costs to society.

The traditional strategy for fabricating a transtibial amputee socket is based upon the assumption that the stump or residual limb is not uniform in its ability to tolerate load.5 Thus, the contours of the residual limb are subjectively modified by the prosthetist to produce a socket (i.e., rectified socket). Most research has focused on improving this socket fabrication process using complex expensive technologies (i.e., Computer Aided Design/Computer Aided Manufacture [CAD/CAM]), or determining the best modifications to produce a well fitting socket (i.e., stress sensors, finite element models, Spiral X-ray Computed Tomography [SXCT]).5-9

We have investigated a new method of shaping the socket.10 Except for a distal end pad, the socket is shaped to the contours of the patient's residual limb (i.e., unrectified socket). Instead of using a labor intensive casting process requiring multiple fittings, or a costly CAD/CAM system, we used a simple, fast, alginate gel process. The purpose of this investigation was to objectively compare rectified and unrectified sockets in transtibial amputees. We hypothesized that there would be no differences between measures as a result of wearing the different sockets.

Methods

Subjects

Forty-three adults with a transtibial amputation (TTA) participated in this investigation. They were recruited through media advertisement (mean age 47±10 years, 36 males 7 females, height 176±8 cm, mass 84±17 kg). All subjects had mature residual limbs and were not undergoing major changes in stump volume due to atrophy or other destabilizing factors. Subjects had been continuously wearing a prosthesis for at least 2 years (mean 20±14). They were independent ambulators with no acute health related problems. Subjects were included if they did not have had constant recurring prosthetic problems (e.g., adherent scar tissue, neuromas, bony protruberances at distal end) and required only accepted standardized fitting components or methods. Subjects were included in the energy expenditure test if their health status did not put them at risk for performing a graded exercise test. All participants signed an informed consent approved by the Washington University Human Studies Committee.

Prosthetic fitting

Each subject wore a prosthesis with 2 different sockets for a minimum of 4 weeks each. The order of wearing the socket was randomized and one of 3 different prosthetists was randomly assigned to each subject. Except for the socket shape, the prostheses were the same. The prosthesis consisted of a laminated epoxy fiberglass socket, pelite or gel liner, aluminum pylon, and various terminal devices (e.g., Seattle lite foot). Componentry was switched between sockets whenever possible. Each socket was fitted to wear with a 3-ply sock or less using the “uniform shrink” feature of a CAD/CAM system. The 3-ply or less socket strategy was used to prevent a buffering effect of multiple ply socks. Such a buffering effect could have altered the fit and comfort of a socket. With a 3 ply or less sock, the existence or nonexistence of socket modifications was clearly evident to the subject.

The prosthetist fabricated the rectified socket using the traditional method. The positive mold was made from a plaster cast and modified based upon the concept that the residual limb was not uniform in its ability to tolerate load. The patient and prosthetist established when the prosthesis was acceptable, but no more than 3 test sockets were permitted.

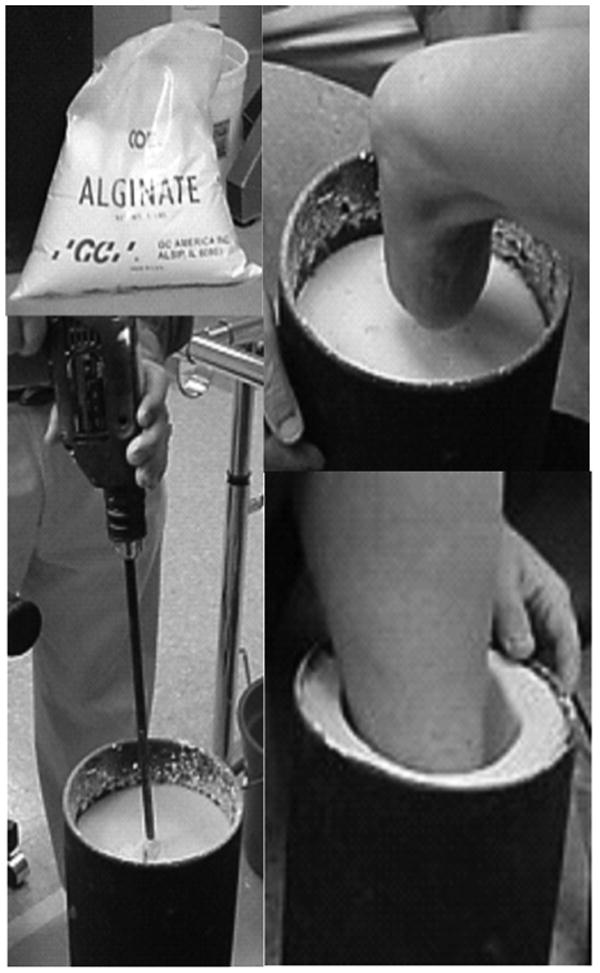

In the unrectified socket fabrication process, the positive plaster mold was made using an alginate casting method (Figure 1). A mixer stirred alginate powder as it was poured into a pail filled with water. After the powder dissolved, the subject placed his/her residual limb into the alginate liquid and stood for approximately 5 minutes while the alginate gelled to a semi-solid state. The subject removed his/her residual limb from the alginate gel leaving a negative mold. Plaster was then immediately poured into the negative alginate mold to make a positive mold. The positive plaster mold was removed and very slightly smoothed with sanding screen. A single test socket was produced only to determine if the socket fit with a 3-ply or less sock. A distal end pad was included during socket fabrication.

Figure 1.

The alginate powder (upper left) was mixed (lower left) and the amputee placed the residual limb in the liquid (upper right). The liquid gelled in about 5 minutes and the subject removed the limb (lower right).

Data collection and analysis

General

The subjects were tested after wearing the first socket (i.e., either the rectified or unrectified randomly selected) for at least 4 weeks. The socket was then replaced with the second socket and subjects were tested a second time after at least another 4 weeks of wearing time. Data from 3 different tests were collected (Engsberg et al., 2003): 1) gait analysis, 2) energy expenditure during gait [36 subjects], and 3) Prosthetic Evaluation Questionnaire [PEQ].11 At the end of participation, each subject chose the socket he/she wished to have on their final prosthesis.

Gait analysis

Video data from 6 camera HiRes Motion Analysis Corporation systems (Motion Analysis Corp., Santa Rosa, CA) captured the images of reflective surface markers during gait (Engsberg et al., 2003). Three markers were placed on each of the feet, legs, thighs, pelvis, and trunk. The subject walked along a 9 m walkway at his/her freely selected speed and video data were collected during the middle 2 m. Kinetic data were also collected from a Kistler force platform (Kistler Inc. Germany). A minimum of 6 trials of data were collected for each subject (3 right steps, 3 left).

The location-time data of the surface markers were tracked (digitized) and converted to three-dimensional coordinates as a function of time. The tracked data were processed using standard software (Motion Analysis Corp., Santa Rosa, CA). The software produced data describing the averaged joint angles as a function of the complete gait cycle for each of the three principal planes of the body. Four specific kinematic variables were determined from these data: 1) minimum knee flexion during stance, 2) minimum hip flexion during stance, 3) maximum trunk lateral flexion, and 4) maximum transverse plane trunk rotation. In addition, linear gait variables including speed, stride length, cadence, and the percentage of prosthetic stance time to nonprosthetic stance time (expressed as a percentage) were determined. The maximum vertical ground reaction force for each leg was determined from the force plate data. The ratio of the prosthetic maximum vertical force to the nonprosthetic maximum (i.e., P/NP) was calculated and expressed as a percentage.

Energy expenditure

Energy expenditure was assessed during a submaximal graded exercise test (G×T) which included four 4-minute stages (Engsberg et al., 2003). The first 2 stages were performed at 0% incline at the rates of 3.2 km/hr (2.0 mph) and 4.0 km/hr (2.5 mph). Stages 3 and 4 repeated the same speeds at 5% incline. The stages increased in intensity from 2.5 Mets to 4.6 Mets [Metabolic equivalent (Met): A multiple of the resting rate of O2 consumption (VO2 rest)]. The protocol incorporated specific work loads that have successfully elicited differences in energy expenditure between prostheses.12,13 When necessary the speeds were reduced by 0.8 km/hr (0.5 mph) or 1.6 km/hr (1 mph) for subjects with exceptionally slow gait patterns.

Precision analyzed gas mixtures and a 3-L calibration syringe (SensorMedics Corp. Yorbana Linda, CA 92687) were used to calibrate the gas analyzers and flow sensor. Oxygen uptake (L/min), pulmonary ventilation(VE), heart rate (bpm), blood pressure (mmHg) and Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) (Borg scale of 6-20) were monitored during each stage of the G×T. Equipment included a Vmax 29 metabolic cart (Sensormedics Corporation, Anaheim, CA.), a Marquette 2000 treadmill, and a Marquette Case 800 12-lead EKG unit (products of G.E. Corp. Medical System, Milwaukee, WI).

The protocol and RPE chart were reviewed with the subject. EKG leads were attached and a supine resting EKG was recorded. The subjects were familiarized with the treadmill (approximately 2-3 minutes) and fitted with a mouth piece, a nose clip, and headgear apparatus. The decision to reduce the protocol speeds was made during the familiarization period. During testing breath-by-breath measures of gas exchange and heart rate were determined and stored for post-test analyses. RPE was recorded during the third minute of each stage as a subjective measure of intensity. Metabolic data were assessed for accuracy and extreme outliers were removed prior to averaging the last 30 seconds of each stage. VO2 was normalized by body mass and reported as ml/(kg*min).

Prosthetic evaluation questionnaire (PEQ)

The PEQ was designed to quantify the patient satisfaction of lower limb amputees. The questionnaire is composed of 9 validated scales (ambulation, appearance, frustration, perceived response, residual limb health, social burden, sounds, utility, well being). The scales have been validated for internal consistency and temporal stability and are scored as a unit. The PEQ has been reported to display good psychometric properties (Legro et al., 1998). The scales are not dependent upon each other and can be used independently, depending upon the need. A composite score is also permitted by averaging the individual scale scores. Each scale and the composite score are reported here. Four weeks is the minimum recommended time between assessments.

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine if significant differences existed between sockets for the all the gait variables, between prosthetic and nonprosthetic sides for lower extremity gait kinematics and kinetics, for energy expenditure and the PEQ (p<0.05). A Chi square test was used to determine if one socket was selected more frequently as the final socket than the other socket (p<0.05).

Results

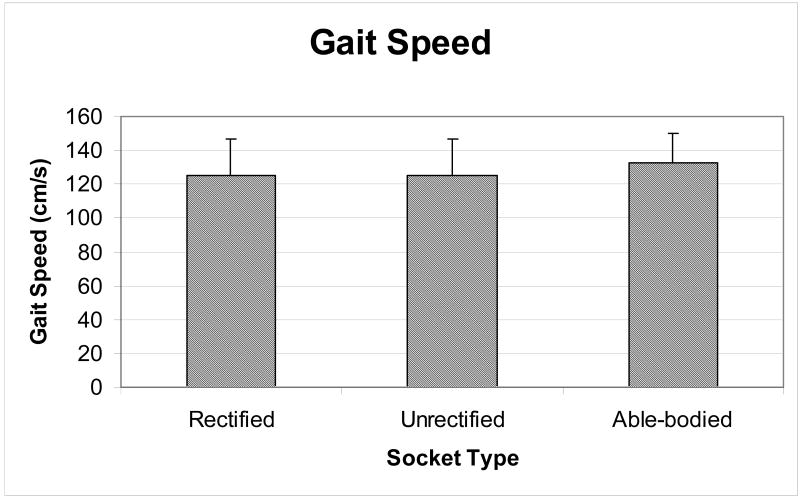

There were no significant differences between socket types for any of the gait variables. For example, gait speed was 125±22 cm/s for the rectified socket and the unrectified socket (Figure 2). Cadence also had identical means and standard deviations, and stride length for both sockets were very close to one another (Table 1). The P/NP stance time, indicating a measure of asymmetry between the prosthetic and nonprosthetic limbs, were 97±5% for the rectified socket and 97±6% for the unrectified socket. A value of 100% indicated that equal time was spent on both limbs during gait. A value of less than 100 indicated less time was spent on the prosthetic limb. The kinetic variables quantifying the maximum vertical ground reaction force also indicated no differences (Table 2). For both the rectified and unrectified sockets, the prosthetic limb had a significantly smaller load than the nonprosthetic limb. For the P/NP maximum vertical ground reaction force ratio between the prosthetic and nonprosthetic sides was another measure of asymmetry. There were no differences (rectified 95±7%, unrectified 96±6%). A value of 100% indicated that an equal maximum force was borne by both limbs during gait. A value of less than 100 indicated less force was borne by the prosthetic limb. The kinematic gait variables also indicated no differences, both between sockets and between limbs (Table 3). For example, the maximum trunk lateral flexion values for both sockets were identical for both means and standard deviations (i.e., rectified 4°±4, unrectified 4°±4). Minimum knee flexion during stance for the prosthetic side was 11° and 10° for the rectified and unrectified sockets, respectively, and 11° for both the nonprosthetic sides, respectively. There was little variability for minimum hip flexion during stance with only 3° separating the prosthetic side from the nonprosthetic side for the rectified socket, and 1° for the unrectified socket.

Figure 2.

Gait speed for subjects wearing both the rectified and unrectified sockets. There was no difference in walking speed as a consequence of wearing the different sockets. Data from adults with able bodies are presented as a point of reference (Waters et al., 1988).

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations ( ) for linear gait variables.

| Gait Speed | Cadence | Stride length | P/NP stance time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socket | cm/s | steps/min | cm | % |

| Rectified | 125 (22) | 105 (11) | 143 (17) | 97 (5) |

| Unrectified | 125 (22) | 105 (11) | 144 (18) | 97 (6) |

| Able-bodied | 133 (17) 1 | 113 (10) 1 | 142 (17) 29 | 100 |

Waters et al., 1988

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations ( ) for prosthetic [P] and nonprosthetic [NP] maximum vertical ground reaction force [VGRF] and prosthetic/nonprosthetic VGRF force ratio.

| Max VGRF | P/NP VGRF | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| % BW | % | ||

| P | NP | ||

| Rectified | 109 (9)ˆ | 116 (10) | 95 (7) |

| Unrectified | 111 (10)ˆ | 116 (9) | 96 (6) |

| Able-bodied | 100 | ||

BW=Body Weight

Significantly different from NP (p<0.00)

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations ( ) for gait kinematic variables.

| Min stance knee flexion | Min stance hip flexion | Max trunk lateral flexion | Max trunk rotation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| degrees | degrees | degrees | degrees | |||

| P | NP | P | NP | |||

| Rectified | 11 (6) | 11(5) | -11 (6) | -14 (6) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) |

| Unrectified | 10 (5) | 11 (6) | -12 (6) | -13 (6) | 4 (4) | 6 (4) |

| Able-bodied | 4 30 | 4 30 | -12 30 | -12 30 | 4 | 6 |

P = Prosthetic leg; NP = Nonprosthetic leg.

Murray et al., 1964

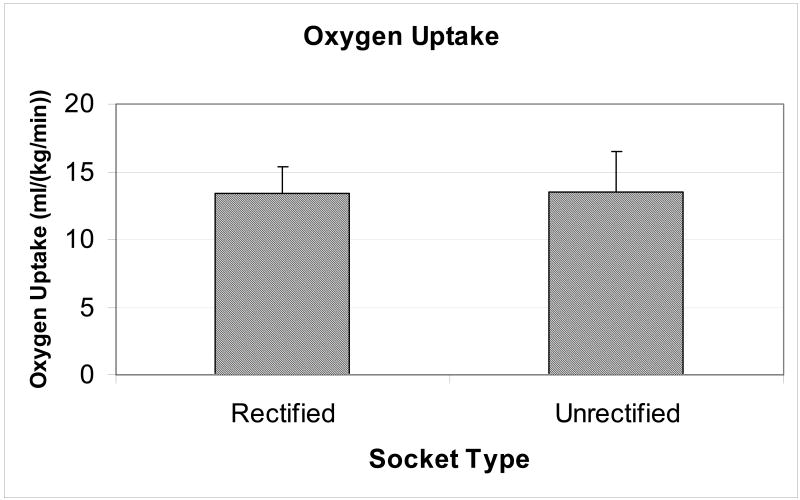

Energy expenditure, as measured by oxygen uptake during the final stage of the G×T, was not different between socket types (Figure 3). The mean values were 13.2±2.3 ml/(kg*min) for the rectified socket and 13.2±2.6 ml/(kg*min) for the unrectified socket. For safety reasons, the test was terminated early for several subjects. Two subjects only completed the first stage due to high heart rate and blood pressure readings. Four subjects only completed 2 or 3 stages due to fatigue or muscle cramping.

Figure 3.

Energy expenditure for subjects wearing both the rectified and unrectified sockets. There was no difference in energy expenditure, as measured by oxygen uptake during the final stage of the graded exercise test (G×T).

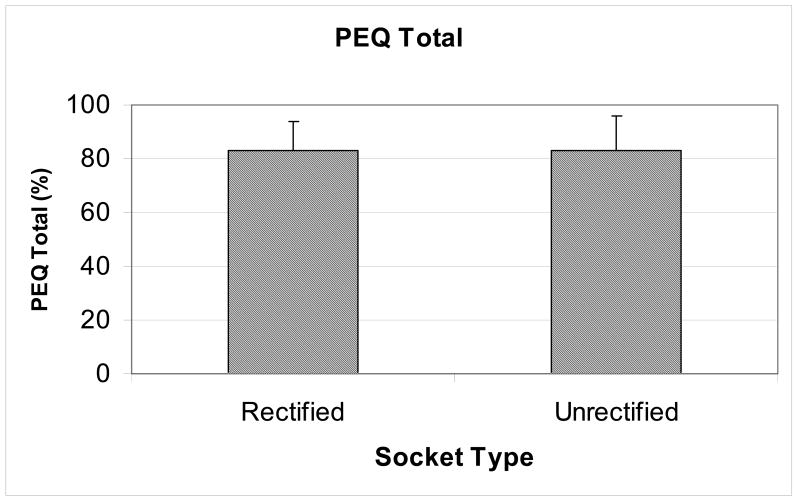

The composite scores for the PEQ quality of life instrument were not significantly different with scores of 82±11% and 81±13 for the rectified and unrectified sockets, respectively (Figure 4). None of the individual domain scores (n=9) for the PEQ were significantly different except for one (Table 4). The Perceived Response was greater for the rectified socket than the unrectified socket.

Figure 4.

Prosthetic Evaluation Questionnaire (PEQ) total scores for subjects wearing both the rectified and unrectified sockets. There was no difference in PEQ total score as a consequence of wearing the different sockets.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations () for the nine domains and the total score of the Prosthetic Evaluation Questionnaire [PEQ].

| Ambula | Appear | Frust | PercResp | ResLimb | SocBurd | Sounds | Utility | WellBe | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Rectified | 83 (17) | 79 (13) | 79 (25) | 98 (4) | 73 (17) | 94 (12) | 65 (29) | 82 (16) | 86 (13) | 82 (11) |

| Unrectified | 81 (21) | 79 (14) | 73 (32) | 91 (14)* | 76 (17) | 92 (13) | 71 (27) | 80 (17) | 85 (20) | 81 (13) |

Ambula=Ambulation, Appear=Appearance, Frust=Frustration, PercResp=Perceived Response, ResLimb=Residual Limb Health, SocBurd=Social Burden, WellBe=Well Being

Significantly different from Rectified (p<0.00)

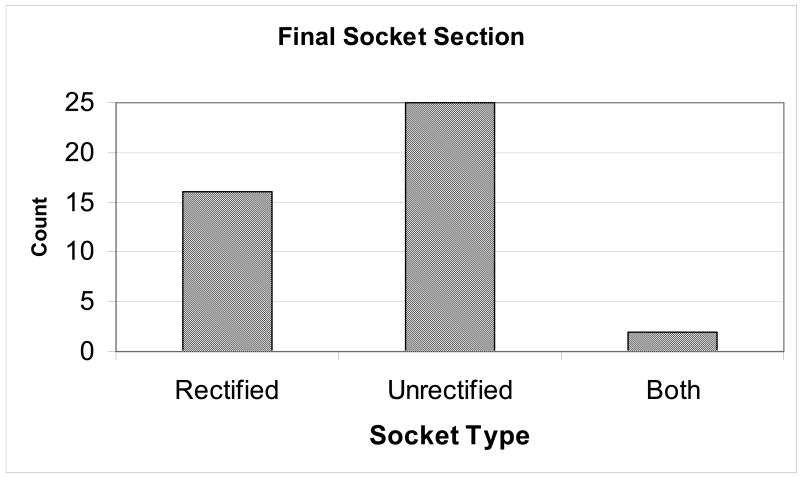

Finally, 16 of the subjects selected the rectified socket as their final prosthesis and 25 selected the unrectified socket (Figure 5). These results were not significantly different. It should be noted that two subjects chose to use both sockets. They used the rectified socket for sedentary tasks, such as work and the unrectified socket for exercise.

Figure 5.

Final socket selection for subjects wearing both the rectified and unrectified sockets. There was no difference in final socket selection. Two subjects chose to use both sockets. They used the rectified socket for sedentary tasks, such as work and the unrectified socket for exercise.

Discussion

The purpose of this investigation was to objectively compare rectified and unrectified sockets in transtibial amputees. At least two limitations are noteworthy. First, the unrectified socket method may not be applicable to all transtibial amputees. Our strategy was to avoid patients with constant recurring prosthetic problems (e.g., adherent scar tissue, neuromas, bony protruberances at distal end) and only fit relatively uncomplicated residual limbs. It was felt that if the method could be adequately applied to the majority of amputees (i.e., 70-80%), then this was a success. Addressing the suitability of the method to difficult cases will be a part of our future work. Second, it was our original intention to only use pelite liners with our sockets. However, early in the project and due to their growing popularity, it became apparent that continued recruitment would become difficult if we did not also include pelite liners. As a result they were included as a socket option.

No previous investigations could be found utilizing the alginate method of casting the residual limb for the purpose of making unrectified prosthetic sockets. The method is quite simple and only involves taking an exact likeness of the residual limb. No attempts are made to artificially modify the tissues during casting. The method may be performed equally well by any prosthetist or technician. To continue with simplicity, few controls or restrictions are placed on the subject. The subject supports him/herself during the process by holding the backs of chairs or railings. The residual limb musculature is relaxed and remains in a relatively vertical orientation with slight knee flexion.

The variables collected in the present investigation are not new to the area of prosthetics. For example gait data has been evaluated relative to different prosthetic feet,14 movement differences between trans-tibial amputees and able-bodied,15-18 and alignment of the prosthetic foot relative to the prosthetic leg.19 Other than our work, no investigations could be found that performed gait analyses as a function of socket design.

Oxygen uptake has been assessed for a number of different scenarios, however none of the comparisons included socket designs.12,14,20-27 The energy expenditure values reported here are in agreement with the values found in the literature for other transtibial amputees walking at similar work intensities. For example, Huang and colleagues (2000) reported values between 12 and 15 ml/(kg*min) for their amputee subjects walking at 3.2 km/hr and grades of 0, 4 and 8%.24

The most important variable of the investigation was the final socket each subject selected to have as part of their exit prosthesis. Since this study involved a novel approach to socket design there were no other studies in the literature which addressed this issue. Thirty-seven percent of the subjects (n=16) selected the rectified socket. Fifty-eight percent (n=25) selected the unrectified socket, and 5% selected to use both sockets. These differences were not significantly different.

Many factors contribute to the selection of the socket. Two points seem relevant to this project. The first is that the PEQ was used to assist with identifying factors that may have contributed to the final socket selection. It was expected that the Ambulation, Residual Limb Health, and Well Being domains would be keys to the selection process, and like the socket selection results, there were no differences between sockets for these variables. Curiously, the only domain that indicated a significant difference was the Perceived Response domain. In this domain information is sought about the reaction to others (i.e., partner or family members) to the prosthesis. It can only be speculated that partners and family members were not entirely receptive to the new type of socket. Additional work in this area is necessary, but it does not seem to be as critical as some as the other domains (e.g., ambulation, residual limb health, and well being) relative to this project.

The second point is that it is possible that socket selection was not entirely based upon the domains of the PEQ. For example, it is possible that some subjects chose rectified socket simply because they had always worn a rectified socket. On the other hand, other subjects may have chosen the unrectified socket because it was experimental. Additional work to uncover the underlying mechanisms of socket fit (e.g., soft tissue distribution, blood flow, socket-residual limb load distribution) may provide additional information in this regard.

The present investigation adds to the body of knowledge in at least two areas. First, there appears to be more than one paradigm for shaping a prosthetic socket for transtibial amputees. The rectified sockets of the present investigation had the typical alterations to the original shape of the residual limb to account for the inability of the residual limb to uniformly tolerate load. In contrast, the unrectified socket only added a distal endpad to the socket. Otherwise the shape of the residual limb was retained. Despite these two different socket fabrication strategies, the results of the objective tests for gait, energy expenditure, and the quality of life questionnaire (PEQ), and final socket selection were not different. These results may offer a unique opportunity to help understand the underlying mechanisms of socket fitting. Since there was not a significant difference in the socket selection, it is possible that factors such as residual limb loading, soft tissue distribution, or blood flow may be optimal for some patients in the rectified socket and for others in the unrectified socket. Such a hypothesis is testable given our current ability to quantify these factors using pressure sensors, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, respectively.

The second addition to the body of knowledge is the simplicity of fabricating the alginate socket. Such simplicity can be used in third world countries where prosthetists and fabrication facilities are scarce or nonexistent. With minimal input from skilled prosthetic personnel patients could be fit with a well fitting socket. If fact, prosthetic “kits” containing the essential elements for an entire prosthesis could be created and sent to third world countries. The simplicity of the method might also be beneficial to new amputees. Since the effort associated with making a new socket is substantially reduced, sockets could be fitted more frequently to better account for residual limb anatomy changes. Finally, the method might also be used in typical prosthetic facilities. It has been reported that 3 test sockets are generally used to fit each amputee with a rectified socket.28 For our investigation only one socket was permitted for the unrectified method. The labor costs associated with the reduction in tests sockets could be substantial. These methods could potentially allow the prosthetist to delegate socket fabrication tasks to less expensive personnel, who could successfully perform these tasks with less expertise, and free the prosthetist to address other important issues to better help the patient.

This investigation used objective measures to compare rectified and unrectified sockets in transtibial amputees. Results indicated no differences between sockets for gait speed and timing, gait kinematics and kinetics, gait energy expenditure. There were no differences in the Prosthetic Evaluation Questionnaire and final socket selection. Results seem to indicate that more than one paradigm exists for shaping prosthetic sockets, and may be helpful in understanding the mechanisms of socket fit. The alginate gel fabrication method was simpler and less time consuming than the traditional method. The method could be helpful in other countries where prosthetic care is lacking, may be helpful with new amputees, and may be helpful in typical clinics to reduce costs and free the prosthetist to focus more time on patient needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (#R01 HD38919).

Reference List

- 1.Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, Mackenzie EJ. Limb amputation and limb deficiency: epidemiology and recent trends in the United States. South Med J. 2002;95:875–883. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200208000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feinglass J, Brown JL, LoSasso A, Sohn MW, Manheim LM, Shah SJ, Pearce WH. Rates of lower-extremity amputation and arterial reconstruction in the United States, 1979 to 1996. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1222–1227. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell JN, Hendershot GE, LeClere F, Howie LJ, Adler M. Trends and differential use of assistive technology devices: United States, 1994. Adv Data. 1997:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engsberg JR, Clynch GS, Lee AG, Allan JS, Harder JA. A CAD CAM method for custom below-knee sockets. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1992;16:183–188. doi: 10.3109/03093649209164338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radcliffe CW, Foort J. The Patellar-Tendon-Bearing Below-Knee Prosthesis. University of California, Biomechanics Laboratory; Berkeley, CA: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Commean PK, Smith KE, Vannier MW. Design of a 3-D surface scanner for lower limb prosthetics: a technical note. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1996;33:267–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders JE, Fergason JR, Zachariah SG, Jacobsen AK. Interface pressure and shear stress changes with amputee weight loss: case studies from two trans-tibial amputee subjects. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2002;26:243–250. doi: 10.1080/03093640208726654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saunders CG, Foort J, Bannon M, Lean D, Panych L. Computer aided design of prosthetic sockets for below-knee amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1985;9:17–22. doi: 10.3109/03093648509164819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steege JW, Schnur DS, Childress DS. Prediction of Pressure at the Below-Knee Socket Intrface by Finite Element Analysis. Biomechanics of Normal and Prosthetic Gait 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engsberg JR, Sprouse SW, Uhrich ML, Ziegler B. Preliminary Investigation Comparing Rectified and Unrectified Sockets for Transtibial Amputees. Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics. 2003;15:119–124. doi: 10.1097/00008526-200601000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:931–938. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielson DH, Shurr DG, Golden JC, Meier K. Comparison of Energy Cost and Gait Efficiency During Ambulation in Below-Knee Amputees Using Different Prosthetic Feet - A Preliminary Report. Journal of Prosthetic Orthotics. 1989;1:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casillas JM, Dulieu V, Cohen M, Marcer I, Didier JP. Bioenergetic comparison of a new energy-storing foot and SACH foot in traumatic below-knee vascular amputations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barth DG, Schumacher L, T SS. Gait Analysis and Energy Cost of Below-Knee Amputees Wearing Six Different Prosthetic Feet. Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics. 1992:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engsberg JR, Lee AG, Patterson JL, Harder JA. External loading comparisons between able-bodied and below-knee-amputee children during walking. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:657–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewallen R, Dyck G, Quanbury A, Ross K, Letts M. Gait kinematics in below-knee child amputees: a force plate analysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1986;6:291–298. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198605000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith AW. A Biomechanical Analysis of Amputee Athlete Gait. International Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 1990:262–282. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winter DA, Sienko SE. Biomechanics of Below-Knee Amputee Gait. J Biomech. 1988;21:361–367. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(88)90142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seliktar R, Mizrahi J. Some gait characteristics of below-knee amputees and their reflection on the ground reaction forces. Eng Med. 1986;15:27–34. doi: 10.1243/emed_jour_1986_015_009_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engsberg JR, Herbert LM, Grimston SK, Fung TS, Harder JA. Relation among indices of effort and oxygen uptake in below-knee amputee and able-bodied children. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:1335–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganguli S, Datta SR, Chatterjee BB, Roy BN. Metabolic cost of walking at different speeds with patellar tendon- bearing prosthesis. J Appl Physiol. 1974;36:440–443. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.4.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez EG, Corcoran PJ, Reyes RL. Energy expenditure in below-knee amputees: correlation with stump length. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1974;55:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herbert LM, Engsberg JR, Tedford KG, Grimston SK. A comparison of oxygen consumption during walking between children with and without below-knee amputations. Phys Ther. 1994;74:943–950. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.10.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang GF, Chou YL, Su FC. Gait analysis and energy consumption of below-knee amputees wearing three different prosthetic feet. Gait Posture. 2000;12:162–168. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(00)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehmann JF, Price R, Boswell-Bessette S, Dralle A, Questad K, deLateur BJ. Comprehensive analysis of energy storing prosthetic feet: Flex Foot and Seattle Foot Versus Standard SACH foot. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:1225–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torburn L, Powers CM, Guiterrez R, Perry J. Energy expenditure during ambulation in dysvascular and traumatic below- knee amputees: a comparison of five prosthetic feet. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1995;32:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waters RL, Perry J, Antonelli D, Hislop H. Energy cost of walking of amputees: the influence of level of amputation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1976;58:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ANCO Engineers Inc. ANCO research in thin film transducers has application in prosthetic design. 2003;2(2) Website: www.ancoengineers.com/Articles.

- 29.Waters RL, Lunsford BR, Perry J, Byrd R. Energy-speed relationship of walking: standard tables. J Orthop Res. 1988;6:215–222. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100060208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray MP, Drought AB, Kory RC. Walking patterns of normal men. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46:335–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]