Abstract

Objective

This longitudinal study examines links between parents' television (TV)-related parenting practices and their daughter's daily TV viewing hours.

Study design

Participants included 173 non-Hispanic white girls and their parents who were examined when girls were age 9 and 11 years. Girls' daily TV viewing hours, mothers' and fathers' daily TV viewing hours, parents' use of TV as a recreational activity, family TV co-viewing, and parents' restriction of girls' access to TV were assessed.

Results

Approximately 40% of girls exceeded the TV-viewing recommendations (ie, ≤2 hours/day). Girls watched significantly more TV when their parents were high-volume TV viewers, relied heavily on TV as a recreational activity, watched TV with them, and failed to limit their access to TV. A parenting risk score was calculated by collapsing information across all parenting variables. In comparison with girls exposed to 1 or fewer parenting risk factors at age 9, girls exposed to 2 or more parenting risk factors were 5 to 10 times more likely to exceed TV viewing recommendations at age 9 and 11.

Conclusions

Efforts to reduce TV viewing among children should encourage parents to limit their own TV viewing, reduce family TV viewing time, and limit their children's access to TV.

U.S. children and adolescents generally watch 2 to 3 hours of television (TV) per day;1 38% watch more than 3 hours per day,2 and 40% of children under age 5 years have a TV in their bedroom.3 Excessive TV viewing among children is of public health concern because it is associated with poor psychosocial and physical health.4-6 A recent study of individuals followed from birth showed that excessive TV viewing between age 5 and 15 years was associated with higher body mass index (BMI), lower fitness, increased incidence of cigarette smoking, and higher serum cholesterol level at age 26, after controlling for childhood BMI, parent BMI, and parent smoking.7

In response to evidence implicating the negative health effects of excessive TV viewing, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released pediatric guidelines for TV viewing in 20018 stating that children older than 2 years should watch no more than 2 hours of quality programming per day, children under age 2 should not watch TV, and TVs should be removed from children's bedrooms. Despite these recommendations, however, there is no evidence that TV viewing has declined among U.S. youth.2 Consequently, the identification of effective targets and methods of intervention to reduce children's TV viewing is a clear research priority.

In contrast with other health-related behaviors, such as alcohol intake, physical activity, and sexual behaviors, TV viewing occurs almost exclusively at home, often in the context of the family. Because parents serve as both models and gatekeepers for children's TV viewing, the family is a key point of intervention in modifying children's TV viewing behaviors. Research suggests that children watch more TV when their parents are high-volume TV viewers9-11 and fail to place limits on their total TV viewing time.12 Thus parents may play an important role in shaping children's TV viewing behaviors. This conclusion is tentative, however, given the absence of longitudinal research.

To our knowledge, to date no longitudinal studies have examined links between parents' TV viewing behaviors and parenting practices and the time that their children spend watching TV. As a result, it is not known whether TV-related parenting practices change across time and whether parenting at one point in time influences children's TV viewing at a later point in time. Furthermore, it is not known whether TV-related parenting practices co-occur in families and cumulatively place children at risk of exceeding TV viewing recommendations across time. The current study was designed to answer these questions by examining parents' TV-related parenting practices and their daughters' TV viewing over a 2-year period.

METHODS

Participants

Families were recruited for participation in the study using flyers and newspaper advertisements. In addition, families with age-eligible female children within a 5-county radius received mailings and follow-up phone calls (Metromail Inc.). Study participants included 187 non-Hispanic white girls and their mothers and fathers from central Pennsylvania who were part of a longitudinal study examining the health and development of young girls. Of the 187 families who completed data collection when their girls were age 9 years (median age, 9.34, ± 0.3 years), 173 were reassessed when the girls were age 11 (median age, 11.34 ± 0.3 years), representing a 93% retention rate. Only families who participated at both times of assessment were included in the analyses. No significant differences in family income, parents' education, and girls' and parents' weekly TV viewing hours were identified between families who remained in the study and those who dropped out. Mothers and fathers were generally well educated, with means of 14.6 (± 2.2) and 14.7 (± 2.6) years of education, respectively. The median family income was > $50,000/year.

Procedures

Families visited the laboratory during summer when the girls were age 9 and again when they were age 11. The girls were individually interviewed by trained interviewers, and the parents completed a series of self-report questionnaires. Trained research assistants measured girls' height and weight. The institutional review board of the associated university approved all study procedures, and parents provided consent for their family's participation before the study began. Girls also provided informed assent.

Measures

Girls' TV viewing

When the girls were 9 and 11 years old, mothers were asked the following question: “How many hours per day does your daughter spend watching TV/videos?” Mothers responded to this question with reference to an average school day and an average nonschool day (ie, weekends or in the summer months). Average hours per day spent watching TV at each age was calculated as follows: (5 × weekday hours + 2 × weekend hours)/7 days.

Parents' TV viewing behaviors and parenting practices

Five dimensions of TV-related parenting were assessed: mothers' daily TV viewing time, fathers' daily TV viewing time, parents' reliance on TV as a recreational activity, family co-viewing practices, and restrictions placed on girls' access to TV. Mothers and fathers completed questions assessing each of these dimensions. With the exception of mothers' and fathers' daily TV viewing time, scores for mothers and fathers were averaged for each construct to provide a single parent or family score without reference to a particular parent (eg, parent use of TV as a recreational activity; family co-viewing, parent restriction of access). Collapsing information for mothers and fathers provided a more reliable “family” score that incorporated multiple variables and reduced the number of parent variables used in analyses. All measures except restriction of girls' access to TV were assessed when girls were age 9 and 11 years; restriction was assessed at age 11 only.

Mothers' and fathers' daily TV viewing hours were assessed using the following question: “On an average day, how many hours do you spend watching TV/videos?” Parents' dependence on TV as a recreational activity was assessed using the following question: “What percentage of your free time do you spend watching TV/videos?” Response options included 1, relatively little (0 to 25%); 2, less than half (25% to 50%); 3, more than half (50% to 75%); 4, almost all (75% to 100%). Family co-viewing practices were assessed using 2 questions; mothers and fathers were asked to rate, using a 4-point scale (from 1 [rarely] to 4 [regularly]), how often they watched TV/videos with their daughter and as a family.

Finally, parents' restriction of girls' access to TV was assessed using questions completed by parents and girls. First, mothers and fathers indicated the extent to which they limited the amount of television their daughter watched. The response options included 1, do not limit; 2, rarely limit; 3, moderately limit; 4, my daughter is only permitted to watch a few select programs or no television at all. Second, the girls indicated whether or not they had a TV in their bedroom. To maintain a 4-point scale for the restriction items, this variable was coded as 1 for yes and 4 for no. With the exception of mothers' and fathers' TV viewing, a single score ranging from 1 to 4 was created for each parenting construct by taking the average for all items addressing the construct, including items for mothers and fathers as mentioned earlier. Mothers' and fathers' TV viewing was a continuous variable; scores ranged from 0 to 5−1/4 hours per day.

Girls' weight status

At age 9 and 11 years, girls' height and weight were measured in triplicate, and average height and weight were used to calculate BMI. Girls' BMI values were converted to age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control growth charts. Girls were classified as at risk for overweight if their BMI percentile was ≥85 and <95 and overweight if their BMI percentile was ≥95.13 The categories of “at risk of overweight” and “overweight” were collapsed for the analyses (ie, ≥85th BMI percentile).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using SAS version 8.01 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC). Previous research has identified significant associations between demographic characteristics, such as income and education, and children's and adults' TV viewing.11,14 Thus family income and mothers' education were entered as covariates in all analyses. Paired t-tests were used to examine whether mean scores for girls' TV viewing and each measure of parenting changed significantly across time. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to assess whether exceeding the AAP TV viewing recommendations predicted the likelihood of girls' being overweight or at risk of overweight (ie, BMI percentile ≥85); cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses were performed. Spearman's rank correlation analysis was used to assess covariation in TV-related parenting behaviors and parenting practices within families (Table I). Spearman's rank correlation analysis was also used to examine cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between each parenting variable and the girls' TV viewing (Table II).

Table 1.

Spearman rank correlations between parents' TV viewing behaviors and parenting practices at both times of assessment

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mothers' TV viewing (9 years) | ||||||||

| 2. Fathers' TV viewing (9) | .30*** | |||||||

| 3. Parents' use of TV as recreational activity (9) | .45*** | .68*** | ||||||

| 4. Family co-viewing (9) | .41*** | .40*** | .33*** | |||||

| 5. Mothers' TV viewing (11) | .74*** | .33*** | .48*** | .38*** | ||||

| 6. Fathers' TV viewing (11) | .36*** | .74*** | .58*** | .23** | .42*** | |||

| 7. Parents' use of TV as recreational activity (11) | .22** | .59*** | .51*** | .22** | .32*** | .69*** | ||

| 8. Family co-viewing (11) | .25*** | .24*** | .19** | .53*** | .29*** | .26*** | .27*** | |

| 9. Parents' restriction of girls' access to TV (11) | -.19*** | -.13 | -.11 | -.11 | -.23** | -.28*** | -.13 | .00 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the girls' age at the time of measurement. Italicized correlations represent stability estimates for each parenting construct. *P < .05

P < .01

P < .001.

Table II.

Spearman rank correlations assessing cross sectional and longitudinal associations between parents' TV-viewing behaviors and parenting practices and girls' TV viewing

|

Correlations with girls' TV viewing |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers' TV viewing | Fathers' TV viewing | Parents' use of TV as recreation | Family co-viewing | Restricting girls' access to TV | |

| Cross-sectional associations | |||||

| Parenting and girls' TV viewing (age 9) | .55*** | .37*** | .35*** | .35*** | - |

| Parenting and girls' TV viewing (age 11) | .47*** | .39*** | .34*** | .22** | .18** |

| Longitudinal associations | |||||

| Parenting (age 9) and girls' TV viewing (age 11)† | .23** | .06 | .20** | .13 | - |

| Change in parenting and girls' TV viewing between age 9 and 11 | -.08 | .08 | .04 | .18* | - |

All analyses partial out the effects of family income and parent education. Parent restriction was assessed only when the girls were age 11.

P < .05

P < .01

P < .001.

Correlations between parenting variables at age 9 and girls' TV viewing at age 11 controlled for the parent variable at age 11.

The final analysis examined the cumulative impact of parenting risks at age 9 (ie, the number of TV-related parenting risk factors to which the girls were exposed at age 9) on the likelihood that girls exceeded TV viewing recommendations at age 9 and 11. To perform this analysis, each parent variable at age 9 was dichotomized as high (ie, 1) or low (ie, 0) based on a mean split. A family risk score ranging from 0 to 4 was created by summing these scores. Family risk scores of 0 and 1 were collapsed to increase the sample size of the referent group. Each family risk score was then entered as a categorical dummy-coded variable into a logistic regression analysis to predict the likelihood of girls exceeding TV viewing recommendations at age 9 and 11, controlling for family income and mothers' education (Table III). Analyses were rerun including girls' weight status at age 9 (BMI percentile < or ≥85th percentile) as an additional covariate, to control for the possibility that parents may have been responding to their child's weight status.

Table III.

Results from logistic regression model predicting the likelihood of girls exceeding TV viewing recommendations at age 9 and 11 years based on their exposure to parenting risk factors at age 9

|

Number of parenting risk factors to which the girls were exposed at age 9 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Percentage of girls in each category who watched >2 hours of TV per day at age 9 and 11 | 8 | 34 | 42 | 50 |

| Likelihood [OR (95% CI)] of girls watching >2 hours of TV per day at age 9 and 11 controlling for covariates | Referent group | 5.4 (1.9 to 15.6) | 7.3 (2.4 to 21.9) | 9.6 (3.1 to 29.8) |

Covariates included mothers' education and family income. An additional analysis was run that included girls' weight status at age 9 as an additional covariate; see the text for results. A total of 68, 44, 33, and 28 girls were exposed to ≤1, 2, 3, and 4 parenting risk factors, respectively.

RESULTS

Girls' TV Viewing

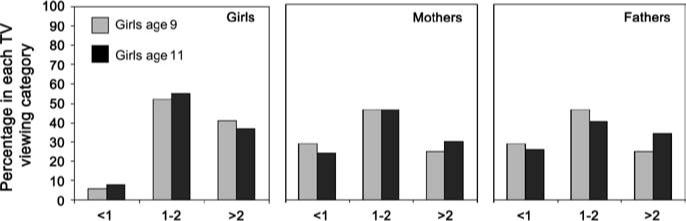

Girls watched slightly less than 2 hours of TV per day at age 9 (1.92 ± .90) and 11 (1.91 ± .91) years, with no significant change across time (P = .98). A high degree of stability was noted in girls' TV viewing across time (r = .73); that is, girls who watched high levels of TV relative to the sample at age 9 also did so at age 11. The percentage of girls (and parents) at age 9 and 11 who spent <1, 1 to 2, and >2 hours per day watching TV is shown in Figure. The proportions of girls in each viewing category did not change substantially across time. The percentage of girls exceeding the AAP TV viewing recommendations of 2 hours per day was 41% at age 9 and 38% at age 11; 35% of girls exceeded TV recommendations at both ages. Few girls (6% to 8%) watched TV <1 hour per day.

Figure.

Percentage of girls, mothers, and fathers watching < 1, 1 to 2, and > 2 hours of TV per day when the girls were age 9 and 11 years.

Exceeding the AAP TV viewing recommendations at age 9 was not associated with the likelihood of being overweight or at risk of overweight at age 9 (odds ratio [OR] = 1.28; 95% confidence interval [CI] = .65 to 2.5). However, girls who exceeded the recommendations at age 9 were marginally more likely to be overweight or at risk of overweight at age 11, controlling for whether or not they exceeded TV viewing recommendations at age 11 (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = .96 to 5.15) and girls who exceeded the TV viewing recommendations at age 11 were more likely to be overweight at age 11 (OR = 2.61; 95% CI = 1.3 to 5.3).

Parents' TV Viewing and TV-Related Parenting

Mothers reported watching approximately 1.5 hours of TV per day when girls were age 9 (1.57 ± .99) and 11 (1.68 ± .97) years, with a significant increase of approximately 7 minutes across time (P < .05). Fathers watched between 1.5 and 2 hours of TV per day (1.63 ± 1.07 at age 9; 1.87 ± 1.09 at age 11), with a significant increase of about 15 minutes across time (t = 3.70; P < .001). The percentage of parents who watched <1, 1 to 2, and >2 hours of TV per day when the girls were age 9 and 11 is presented in the Figure. Approximately 30% of mothers and fathers reported watching TV for more than 2 hours per day, and this figure increased slightly across time (from 25% to 30% for mothers and from 25% to 34% for fathers).

With respect to the other dimensions of TV-related parenting, less than 1 in 10 parents reported devoting 50% or more of their free time to watching TV, and approximately 25% of parents reported watching TV either with their daughter or as a family relatively often or on a regular basis. The mean score for parents' reliance on TV viewing as a recreational activity increased significantly across time from 1.49 (± .53) when the girls were age 9 to 1.58 (± 53) when the girls were age 11 (P = .02). In contrast, the mean level of family co-viewing did not change significantly across time (2.16 ± .52 at age 9 vs 2.19 ± .52 at age 11; P = .29). Finally, at age 11, 40% of the girls reported having a TV in their bedroom, and approximately 50% of the mothers and fathers reported rarely limiting the time that their daughter could watch TV.

Table I presents associations between parents' TV viewing behaviors and parenting practices across both measurement occasions. Results generally showed that parenting behaviors clustered within families. With the exception of parental restriction, all measures of parenting were significantly correlated within and across measurement occasions. For example, mothers and fathers who watched more TV when their daughters were age 9 relied more heavily on TV as a recreational activity and reported higher levels of family co-viewing when their daughters were age 9 and 11. With respect to parent restriction, mothers (when the girls were 9 and 11) and fathers (when the girls were 9) who watched more TV were less likely to restrict their daughters' access to TV when they were age 11.

Associations Between Parents' TV Viewing Behaviors and Parenting Practices and Girls' TV Viewing

All parent TV-related behaviors and parenting practices were concurrently associated with girls' TV viewing at age 9 and 11 (Table II). At age 9, girls watched significantly more TV if their parents were high-volume TV viewers, relied heavily on TV as a recreational activity, or regularly watched TV with them as a family. The same associations were identified at age 11, in addition to a negative association between parents' restriction of girls' access to TV and girls' TV viewing. For the longitudinal associations, higher TV viewing among mothers and greater parental use of TV as a recreational activity when girls were age 9 were linked with higher levels of TV viewing among girls at age 11 after controlling for the respective parenting variables at age 11. No associations between changes in girls' TV viewing and changes in each parenting construct were identified.

Effect of TV-Related Parenting at Age 9 on Girls' Risk of Exceeding TV Viewing Recommendations at Age 9 and 11

In comparison with the girls exposed to 1 or fewer parenting risk factors at age 9, those exposed to 2, 3, or 4 parenting risk factors were 5.4, 7.3, and 9.6 times more likely, respectively, to exceed TV viewing recommendations at age 9 and 11. These effects were independent of income and mothers' education. Furthermore, results did not differ when girls' weight status (≥85th BMI percentile) was entered into the analyses as an additional covariate.

DISCUSSION

The present study has revealed that parents' TV-related behaviors and parenting practices are associated with their daughters' TV viewing at age 9 and 11 years. Approximately 40% of the girls in this sample exceeded the AAP recommendations for TV viewing, mirroring U.S. national rates.1 At age 9 and 11, girls watched significantly more TV when their parents reported higher levels of TV viewing, corroborating findings from previous studies.9-11 Furthermore, girls watched significantly more TV when their parents relied on TV as a leisure activity, reported watching television as a family, and did not limit their access to TV. These parenting behaviors cumulatively increased girls' risk for exceeding the AAP recommendations for TV viewing. Girls exposed to 2 or more parenting risk factors at age 9 were 5 to 10 times more likely to exceed recommendations at age 9 and 11 than were girls exposed to 1 or fewer risk factors.

The consistent pattern of associations between parenting practices and girls' TV viewing at each age and across age 9 to 11 years highlights the important role that parents play in shaping their children's TV viewing behaviors. Results from the longitudinal correlation analyses showed that although there was no association between change in parenting behaviors and change in girls' TV viewing, there was a delayed effect of parenting across ages 9 and 11 years on girls' TV viewing. Specifically, girls watched more TV at age 11 when their parents reported watching more TV (mothers only) and relying more heavily on TV viewing as a recreational activity 2 years earlier, when girls were age 9; these effects were independent of parental risk factors at age 11. Furthermore, total exposure to parental risk factors at age 9 predicted the likelihood of repeatedly exceeding recommendations across time (ie, at age 9 and 11 years). There was a dose-type pattern such that the girls exposed to 2, 3, or 4 parenting risk factors were approximately 5, 7, and 10 times more likely, respectively, to exceed recommendations at age 9 and 11 than were girls exposed to 1 or fewer parenting risk factors.

Parental behaviors shape family environments that can promote similar behaviors in their children, and these relationships between parent and child behaviors can contribute to familial similarities in risk outcomes. Parents' eating and activity behaviors are linked with parent-child similarities in adiposity.15,16 Additional studies provide evidence for similarities in parents' and children's activity patterns,17 eating behaviors,18 and dietary patterns.19-21 These findings substantiate the crucial role that parents play in shaping their children's behaviors through modeling and parenting practices.

As with these and other parent-child relationships, similarities in parents' and children's behaviors may also be a result of parents responding to children's behaviors and preferences. In the case of TV viewing, children's requests to watch TV and their preference for TV over other forms of activity may drive parents' TV viewing as well. Parents, in wanting to spend time with their children, may choose to participate in activities they know their children enjoy, such as TV viewing. It is also possible that similarities in children's and parents' TV viewing could partially reflect a genetic influence on leisure activities.22 Nonetheless, the important role of parents should not be downplayed. It is the parents' responsibility to create a household environment that facilitates their children's health and development. The challenge lies in finding ways to encourage parents to turn off the TV and to identify alternatives to TV viewing as a recreational activity for themselves and their children.

Based on findings from this study, advice for parents should include limiting their own TV viewing time and the time they spend watching TV as a family, as well as decreasing their children's access to TV. At first glance, the recommendation to limit family co-viewing appears to be in conflict with the AAP recommendation that parents watch TV with their children to monitor their viewing content. But the AAP recommendation is focused primarily on young children. In our sample of girls in late childhood, co-viewing was linked with higher levels of TV viewing, suggesting that there can be too much co-viewing and that co-viewing may undermine the AAP recommendation to limit children's TV viewing to no more than 2 hours per day. In addition, research shows that parents watch TV with their older children because of shared viewing preferences rather than for the purpose of monitoring viewing content.23 Parents can limit their children's access to TV by removing TVs from children's bedrooms. In addition to being associated with increased hours of TV viewing,3 the presence of a TV set in a child's bedroom has been linked to an increased risk of overweight,3 fewer hours of reading,24 and sleep disturbances25 in children. Parents can also limit their children's TV viewing time by encouraging them to be selective viewers, choosing only a few favorite programs to watch, as suggested by Salon et al.26

Key strengths of this study include its longitudinal design and the broad assessment of TV-related parenting practices. However, findings from this study cannot be generalized beyond white middle-class families. Consequently, our findings are only a first step in understanding the links between parents' TV-related parenting and children's TV viewing in American families. Additional research with more diverse samples, and samples including boys, is needed to extend the generalizability of these findings. It is also possible that other factors, including neighborhood safety and access to recreational spaces, are important determinants of children's TV viewing; however, we did not collect information on these factors. Finally, findings from this study are limited by the use of retrospective parent-reported measures of TV viewing. Future work could build on these findings by using objective measures of TV viewing or repeated measures of TV viewing through the use of time sampling.

Children can learn to choose and prefer activities other than TV viewing, playing video games, and using the computer. The challenge is to provide guidance and support for parents that will promote this objective. To encourage their children to engage in other forms of activity, parents must serve as role models and create environments that allow and encourage their children to engage in alternate activities. The TV Turnoff Network (www.tvturnoff.org) provides guidance for parents in this area. Reducing their children's TV viewing will require that parents turn off the TV, limit their children's access to TV in the home, adopt new hobbies that require activity, and find or create outdoor settings that will support their and their children's engagement in creative and non–TV-related activities.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the girls in the study group and their families, who continue to show commitment to the larger longitudinal project. In addition, the services provided by the General Clinical Research Center of the Pennsylvania State University were appreciated. Finally, we thank Simon Marshall for his helpful comments on the statistical analyses.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants HD 32973, HD 46567−01, and M01 RR10732.

Glossary

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- OR

Odds ratio

- TV

Television

REFERENCES

- 1.Nielson Media Research . Report on television. New York: 1998. author. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunbaum J, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Lowry R, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States 2003. MMWR. 2004;53(SS2):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennison B, Erb T, Jenkins P. Television viewing and television in bedroom associated with overweight risk among low-income preschool children. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1028–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozmert E, Toyran M, Yurdakok K. Behavioral correlates of television viewing in primary school children evaluated by the child behavior checklist. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:910–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.9.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Proctor MH, Moore LL, Gao D, Cupples LA, Bradlee ML, Hood MY, et al. Television viewing and change in body fat from preschool to early adolescence: the Framingham Children's Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:827–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Troiano RP, Bartlett SJ, Macera CA, Andersen RE. Television watching, energy intake, and obesity in US children: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988−1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:360–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hancox RJ, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Association between child and adolescent television viewing and adult health: a longitudinal birth cohort study. Lancet. 2004;364:257–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16675-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Public Education Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107:423–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGuire M, Hannan P, Neumark-Sztainer D, Falkner N, Story M. Parental correlates of physical activity in a racially/ethnically diverse adolescent sample. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:253–61. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holman J, Braithwaite A. Parental lifestyles and children's television viewing. Aust J Psychol. 1982;34:375–82. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodard EH, Gridina N. Media in the home: the fifth annual survey of parents and children 2000. The Annnenburg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia: 2000. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.St. Peters M, Fitch M, Huston A, Wright J, Eakins D. Television and families: what do young children watch with their parents? Child Dev. 1991;62:1409–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Advance data from vital and health statistics. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2000. Report no. 314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorely T, Marshall SJ, Biddle S. Couch kids: correlates of television viewing among youth. Int J Behav Med. 2004;11:152–63. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1103_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davison KK, Birch LL. Child and parent characteristics as predictors of change in girls' body mass index. Int J Obes. 2001;25:1834–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davison KK, Birch LL. Obesigenic families: parents' physical activity and dietary intake patterns predict girls' risk of overweight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:1186–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davison K, Cutting T, Birch L. Parents' activity-related parenting practices predict girls' physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1589–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000084524.19408.0C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cutting TM, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Birch LL. Like mother, like daughter: familial patterns of overweight are mediated by mothers' dietary disinhibition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:608–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher J, Mitchell D, Smiciklas-Wright H, Mannino M, Birch L. Meeting calcium recommendations from ages 5 to 9 reflects mother-daughter beverage choices and predicts bone mineral status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:698–706. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher JO, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. Parental influences on young girls' fruit and vegetable, micronutrient, and fat intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:58–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher JO, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. Maternal milk consumption predicts the trade-off between milk and soft drinks in young girls' diets. J Nutr. 2001;131:246–50. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plomin R, Corley R, DeFries J, Fulker D. Individual differences in television viewing in early childhood: nature as well as nurture. Psychol Sci. 1990;1:371–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorr A, Kovaric P, Doubleday C. Parent-child coviewing of television. J Broad Elec Media. 1989;33:35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiecha JL, Sobol AM, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Household television access: associations with screen time, reading, and homework among youth. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1:244–51. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001<0244:htaaws>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gutin B, Owens S, Okuyama T, Riggs S, Ferguson M, Litaker M. Effect of physical training and its cessation on percent body fat and bone density of children with obesity. Obes Res. 1999;7:208–14. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salmon J, Ball K, Crawford D, Booth M, Telford A, Hume C, et al. Reducing sedentary behaviour and increasing physical activity among 10-year old children: Overview and process evaluation of the “switch-play” intervention. Health Promo Int. 2005;20:7–17. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]