Abstract

In this report, we present in vitro and in vivo evaluation of three 111In-labeled DTPA conjugates of a cyclic RGDfK dimer: DTPA-Bn-SU016 (SU016 = E[c(RGDfK)]2; DTPA-Bn = 2-(p-isothiocyanobenzyl)diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid), DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 (E = glutamic acid) and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 (Cys = cysteic acid). The integrin αvβ3 binding affinities of SU016, DTPA-Bn-SU016, DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 were determined to be 5.0 ± 0.7 nM, 7.9 ± 0.6 nM, 5.8 ± 0.6 nM and 6.9 ± 0.9 nM, respectively, against 125I-c(RGDyK) in binding to integrin αvβ3, suggesting that E or Cys residue has little effect on the integrin αvβ3 affinity of E[c(RGDfK)]2. It was also found that the 111In-labeling efficiency of DTPA-Bn-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 is 3–5 times better than that of DOTA analogs due to fast chelation kinetics and high-yield 111In-labeling under mild conditions (e.g. room temperature). Biodistribution studies were performed using BALB/c nude mice bearing U87MG human glioma xenografts. 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 all displayed a rapid blood clearance. Their tumor uptake was comparable between 0.5 h and 4 h postinjection (p.i.) within experimental error. 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 had a significantly lower (p < 0.01) kidney uptake than 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016. The liver uptake of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 was 1.69 ± 0.18 %ID/g at 24 h p.i. while the liver uptake of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 was 0.55 ± 0.11 %ID/g and 0.79 ± 0.15 %ID/g at 24 h p.i., respectively. Among the three 111In radiotracers evaluated in this study, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 has the lowest liver and kidney uptake and the best tumor/liver and tumor/kidney ratios. Results from metabolism studies indicated that there is little (<10%) metabolism for three 111In radiotracers at 1 h p.i. Imaging data showed that tumors can be clearly visualized at 4 h p.i. with good contrast in the tumor-bearing mice administered with 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016. It is concluded that using a glutamic acid linker can significantly improve excretion kinetics of the 111In-labeled E[c(RGDfK)]2 from liver and kidneys.

INTRODUCTION

Integrin αvβ3 plays a critical role in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis (1–5). The highly restricted expression of integrin αvβ3 during tumor growth, invasion and metastasis makes it an interesting molecular target for development of the integrin αvβ3-targeted radiotracers (6–9). In the last decade, many radiolabeled cyclic RGD peptides have been evaluated as potential radiotracers for early detection of the integrin αvβ3-positive tumors by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET). [18F]Galacto-RGD has become the first PET radiotracer under clinical investigation for noninvasive visualization of integrin αvβ3 expression in cancer patients (10–12). The integrin αvβ3-targeted radiotracers have been reviewed extensively (13–18).

We and others have been using cyclic RGD dimers, such as E[c(RGDfK)]2 (SU016), to develop integrin αvβ3-targeted diagnostic (64Cu, 99mTc and 111In) and therapeutic (90Y and 177Lu) radiotracers (19–36). It has been found that the radiolabeled cyclic RGD dimers have much better tumor uptake than monomeric analogs due to their higher integrin αvβ3 binding affinity. Recently, we reported the impact of pharmacokinetic modifying (PKM) linkers on biological properties of the 99mTc-labeled HYNIC-PKM-SU016 (HYNIC= 6-hydrazinonicotinamide; PKM = glutamic acid (E), lysine (K) or PEG4 (15-amino-4,7,10,13-tetraoxa-pentadecanoic acid)) (23). Even though they have minimal impact on integrin αvβ3 affinity of SU016, all three PKM linkers are able to reduce the radiotracer uptake in blood, kidneys, liver and lungs, and increase target-to-background (T/B) ratios. E and K have advantages over PEG4 due to lower liver uptake and higher tumor/liver ratios of the 99mTc-labeled E[c(RGDfK)]2 (23). For 111In-labeled DOTA-PKM-E[c(RGDfK)]2 (DOTA = 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid), however, PEG4 appears to be a better linker than E and K since 111In-DOTA-PEG4-E[c(RGDfK)]2 has the highest tumor-to-blood ratio and lowest uptake in liver and kidneys (33).

The disadvantage of using DOTA as the bifunctional chelator (BFC) for 111In-labeling of small biomolecules is its slow chelation kinetics and low radiolabeling efficiency (33, 37, 38). In contrast, DTPA has higher radiolabeling efficiency (37–39), and have been successfully used for 90Y, 177Lu and 111In-labeling of biomolecules, including antibodies (40–44) and small peptides (39, 40, 45, 46). In this study, we report three new cyclic RGDfK dimer DTPA conjugates, DTPA-Bn-SU016 (DTPA-Bn = 2-(p-isothiocyanobenzyl)diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid), DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 (Cys = cysteic acid), and the evaluation of their 111In complexes (Figure 1) as the integrin αvβ3-targeted radiotracers in the BALB/c nude mice bearing U87MG human glioma xenografts. 111In is of our particular interest since it has been widely (second only to 99mTc) used for SPECT imaging, and the 111In-labeled E[c(RGDfK)]2 can be used as the imaging surrogate to evaluate the potential of the 90Y-labeled E[c(RGDfK)]2 as integrin αvβ3-targeted radiotracer for tumor radiotherapy. The main objective of this study is to explore the effect of linkers (E and Cys) on biodistribution characteristics of the 111In-labeled E[c(RGDfK)]2. The ultimate goal of using different linkers is to increase T/B ratios by minimizing radiotracer uptake in non-tumor organs while maintaining high tumor uptake.

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of 111In-labeled cyclic RGDfK dimer DTPA conjugates: 111In(DTPA-Bn-PKM-SU016) (PKM = direct bond, glutamic acid (E) and cysteic acid (Cys); SU016 = E[c(EGDfK)]2).

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma/Aldrich, unless specified. The cyclic pentapeptide, c(RGDfK), was obtained from Peptides International, Inc. (Louisville, KY). 2-(p-Isothiocyanobenzyl)diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (p-SCN-Bn-DTPA) was purchased from Macrocyclics (Dallas, TX). 111InCl3 was obtained from Perkin-Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences (North Billarica, MA). E[c(RGDfK)]2 and E-E[c(RGDfK)]2 were prepared according to the procedure described in our previous communications (21, 23). The reversed-phase C-18 SepPak cartridges were obtained from Waters (Milford, MA). The ammonium acetate buffer for 111In-labeling studies was passed over a Chelex-100 column (1×15 cm) to minimize the trace metal contaminants.

HPLC and ITLC Methods

The HPLC Method 1 used a LabAlliance semi-prep HPLC system equipped with a UV/vis detector (λ = 254 nm) and a reverse phase Zorbax C18 column (9.4 mm × 250 mm, 100 Å pore size). The flow rate was 2.5 mL/min. The mobile phase was isocratic with 90% solvent A (0.1% acetic acid in water) and 10% solvent B (0.1% acetic acid in acetonitrile) at 0–5 min, followed by a gradient mobile phase going from 90% solvent A and 10% solvent B at 5 min to 60% solvent A and 40% solvent B at 20 min. The radio-HPLC method (Method 2) used a HP Hewlett® Packard Series 1100 HPLC system equipped with Radioflow Detector LB509 and Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm). The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. The mobile phase was isocratic with 90% solvent A (25 mM NaOAc buffer, pH=5.0) and 10% solvent B (acetonitrile) at 0–2 min, followed by a gradient mobile phase going from 10% solvent B at 2 min to 15% solvent B at 5 min and to 20% solvent B at 20 min, then to 10% solvent B at 25 min. The radio-ITLC method used GelmanSciences silica-gel paper strips and a 1:1 mixture of acetone and saline as the eluant. Using this method, the 111In labeled cyclic RGDfK peptide dimer migrates to the solvent front while the “free” or “unchelated” 111In remained at the origin.

DTPA-Bn-SU016

DTPA-Bn-SCN (2.7 mg, 4 μmol) and SU016 (3.0 mg, 2 μmol) were dissolved in 1 mL of anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF). The pH in the reaction mixture was adjusted to 8.5–9.0 with DIEA. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for ~6 h. After addition of 3 mL of 100 mM NH4OAc buffer (pH = 7.0), the resulting solution was filtered, and the filtrate was subjected to HPLC-purification (Method 1). The fraction at ~15 min was collected. Lyophilization of the collected fractions afforded the expected product as a white power. The yield was 1.8 mg (48%). ESI-MS (positive mode) for DTPA-Bn-SU016: m/z = 1859.62 for [M + H]+ (M = 1858.82 calcd. for C81H116N23O26S).

DTPA-Bn-E-SU016

DTPA-Bn-SCN (2.7 mg, 4 μmol) and E-E[c(RGDfK)]2 (3.0 mg, 2 μmol) were dissolved with anhydrous DMF (1 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. DIEA was added to adjust pH to ~8.0. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 6 h. After addition of 100 mM NH4OAc buffer (3 mL, pH = 7.0), the resulting solution was subjected to semi-prep HPLC purification (Method 1). The fractions at ~17.5 min were collected. Lyophilization of collected fractions gave the desired product as a white powder. The yield was 1.5 mg (38%). ESI-MS (positive mode) for DTPA-Bn-E-SU016: m/z = 1989.68 for [M + H]+ (M = 1988.87 calcd. for C86H124N24O29S).

BOC-Protected Cysteic acid (Boc-Cys-OH)

To a solution of cysteic acid hydrate (0.56 g, 3 mmol) and triethylamine (0.61 g, 6 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (10mL) was added a solution of di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (0.78 g, 3.6 mmol) in 5 mL of DMF. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48 h. Evaporation of solvent under vacuum gave colorless oil. The residue was dissolved in methylene chloride (10 mL). Upon addition of diethyl ether (30 mL) with vigorous steering, the white precipitate was formed. Solvents were decanted and discarded. The solid residue was washed with anhydrous diethyl ether (10 mL), and dried under vacuum to give a foam-like white solid. The yield was 0.89 g (80%). 1H NMR (δ in ppm, CDCl3): 6.60 (d, NH, J = 5.4 Hz), 3.78 (m, 1H, CH), 2.45(m, 2H, CH2), 1.15(s, 9H, t-Bu).

BOC-Protected Cysteic Acid Succinimidyl Ester (Boc-Cys-OSu)

To a solution of Boc-Cys-OH (as its triethylamine salt) (0.89 g, 2.4 mmol) and NHS (0.345 g, 3 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (20 mL) was added DCC (0.618 g, 3 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Acetic acid (1.0 mL) was added into the mixture above and the stirring was continued for 3 h. The precipitate DCU was filtered off. The filtrate was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in methylene chloride (15 mL). Upon removal of a small amount of DCU precipitate, the expected product was precipitated out by adding the filtrate into anhydrous diethyl ether (30 mL). The solid was washed with diethyl ether (20 mL), and dried under vacuum to give a white solid. The yield was 1.20 g (100%). 1H NMR (δ in ppm, CDCl3): 6.46(s, 1H, NH), 4.88(m, 1H, CH), 3.40(m, 2H, CH2), 2.80(s, 4H, CH2CH2), 1.42(s, 9H, t-Bu).

Boc-Cys-SU016

To a solution of Boc-Cys-OSu (7.2 mg, 0.015 mmol) in DMF (1 mL) was added SU016 (13.2 mg, 0.01 mmol). DIEA was added to adjust pH in the reaction mixture to 8.5–9.0. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min, and the pH was adjusted to ~8.5, if necessary. The reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight. The desired product was isolated from the reaction mixture by HPLC purification (Method 1). The collected fractions at ~15 min were combined. Lyophilization of the combined fractions afforded the expected product as a white powder. The yield was 6.4 mg (41%). ESI-MS (positive mode) for Boc-Cys-SU016: m/z = 1570.75 for [M + H]+ (M = 1569.71 calcd. for C67H101N20O22S).

Cys-SU016

Boc-Cys-SU016 (5 mg, 0.003 mmol) was treated with 2 mL of anhydrous trifluoroacetate (TFA) at room temperature for 30 min. Volatiles were completely removed under vacuum. The residue was dissolved in 100 mM NH4OAc buffer (3 mL). The resulting solution was filtered, and the filtrate was purified by HPLC (Method 1). The fractions at ~15.5 min were collected. Lyophilization of collected fractions gave the desired product as a white powder (3.5 mg). ESI-MS (positive mode) for Cys-SU016: m/z = 1469.57 for [M + H]+ (M = 1468.65 calcd. for C62H92N20O20S).

DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016

DTPA-Bn-SCN (2.7 mg, 4 μmol) and Cys-SU016 (3.0 mg, 2 μmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF (1 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. DIEA was used to adjust pH in the mixture to 8.5–9.0. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for another 6 h while maintaining pH at 8.5–9.0. Upon addition of 100 mM NH4OAc (3 mL, pH = 7.0), the resulting solution was filtered. The filtrate subjected to HPLC purification (Method 1). The fractions at ~15.5 min were collected. Lyophilization of collected fractions gave the desired product as a white powder. The yield was 1.5 mg (35%). ESI-MS (positive mode) for DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016: m/z = 2012.08 for [M + H]+ (M = 2010.81 calcd. for C84H122N24O30S2).

111In-Labeling and Solution Stability

To a clean Eppendorf tube were added 200 μL of DTPA-Bn-SU016 or DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 or DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 solution (0.2–0.5 mg/mL in 0.2 M NaOAc buffer, pH=5.5), and 15 μL of 111InCl3 solution (1–5 mCi, in 0.05 M HCl). The reaction mixture was kept at room temperature for 20 min. A sample of the resulting solution was analyzed by radio-HPLC and ITLC. The solution stability of all three radiotracers was determined in saline and 6 mM EDTA solution (pH=5.0). Samples were analyzed by radio-HPLC at 2, 8, 12 and 24 h after Sep-Pak C-18 purification.

Doses Preparation

All 111In radiotracers for animal studies were purified with Sep-Pak C-18 cartridge. To chelate free 111In, 30 μL of EDTA (6 mM, pH=5.5) was added to the reaction mixture 5 min before purification. The cartridge was activated with ethanol (10 mL), followed by H2O (10 mL). After radiotracer was loaded, the cartridge was washed with saline (10 mL). The radiotracer was eluted with 80% ethanol (0.4 mL). Volatiles were completely removed under vacuum. Doses for animal studies were made by dissolving the purified radiotracer in saline to 80 μCi/mL for biodistribution studies, and 2.0 mCi/mL for metabolism or imaging studies. For the blocking experiment, E[c(RGDfK)]2 was used as the blocking agent. Doses were prepared by dissolving E[c(RGDfK)]2 in saline to give a final concentration of 3.0 mg/mL. Each tumor-bearing mouse was injected with 0.1 mL of solution (~15 mg/kg).

Water-Octanol Partition Coefficient

All three 111In radiotracers were purified with Sep-Pak C-18 cartridge to avoid interference from radioimpurities. The purified radiotracer was dissolved in a equal volume mixture of 25 mM phosphate buffer (3 mL, pH = 7.4) and n-octanol (3 mL). After stirring for ~20 min at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at a speed of 8,000 rpm for 5 min. Samples (in triplets) from aqueous and n-octanol layers were counted in a γ-counter (Wallac 1470-002, Perkin Elmer, Finland). Partition coefficients were calculated. The log P value was measured three times and reported as an average of three independent measurements plus the standard deviation.

Integrin αvβ3 Receptor Binding Assay

The in vitro integrin-binding affinities and specificities of cyclic RGD peptides were determined in a whole-cell displacement assay using 125I-c(RGDyK) as the integrin-specific radioligand. 125I-c(RGDyK) was prepared in high specific activity (~1200Ci/mmol) according to the literature method (55). The receptor binding experiments were performed using U87MG human glioma cells. In short, the U87MG glioma cells were seeded in 24-well plates (2 ×105 cells/well) and incubated overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) to allow adherence. During the cell-binding experiments, the plates were rinsed twice with binding buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, 0.1% BSA). The glioma cells were incubated with 125I-c(RGDyK) in the presence of a cyclic RGD peptide (0–1000 nM). The total incubation volume was then adjusted to 300 μL. After the glioma cells were incubated at 4°C for 2 h, the supernatant was removed. The glioma cells were washed three times with cold binding buffer, were then dissolved with 2 M NaOH at 37°C. The cell-associated radioactivity was collected and determined using a γ-counter (Wallac 1470-002, Perkin Elmer, Finland). The same experiments were carried out twice with quadruple samples for each. The IC50 values were calculated by fitting the data by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The IC50 values are reported as an average of samples plus the standard deviation.

Animal Model

The human U87MG human glioma cells from Professor Jingde Zhu (Shanghai Cancer Research Institute) were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Female BALB/c nude mice (4–5 weeks of age) were purchased from Department of Animal Experiment, Peking University Health Center. The U87MG cells (5 × 106) were implanted subcutaneously into the right upper flanks of mice. When tumors reached ~0.8 cm in mean diameter, the tumor-bearing mice were used to biodistribution and imaging studies.

Biodistribution

Biodistribution studies were performed by Dr. Wang’s group in accordance with guidelines of Peking University Health Science Center Animal Care Committee. Sixteen tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into four groups. Each animal was administered intravenously with ~8 μCi of 111In radiotracer via tail-vein. Four animals were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (45.0 mg/kg), and sacrificed by cervical dislocation at 0.5, 1, 4 and 24 h p.i. Blood, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, stomach, intestine, muscle, bone and tumor were harvested, weighed, and measured for radioactivity in a γ-counter (Wallac 1470-002, Perkin Elmer, Finland). Organ uptake was calculated as a percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). In the blocking experiment, each animal was administered with excess E[c(RGDfK)]2 30 min prior to injection of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016. Four animals were sacrificed at 4 h p.i. for biodistribution using the same procedure.

Gamma Imaging

The imaging study was performed by administering with 200 μCi of 111In-DTPA-Bz-E-SU016 in 0.1 mL saline into each animal via tail vein. Animals were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital at a dose of 45.0 mg/kg, then were placed supine on a two-head γ-camera (SIEMENS, E. CAM) equipped with a parallel-hole, middle-energy, and high-resolution collimator. Anterior images were acquired at 4 h and 24 h p.i. and stored digitally in a 128 × 128 matrix. The acquisition count limits were set at 200 K. After completion of imaging, animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation.

Metabolism

The metabolic stability of all three 111In radiotracers was evaluated in normal BALB/c mice. Each mouse was administered with 200 μCi of the radiotracer in 0.1 mL saline via intravenous injection. Urine samples were collected at 1 h postinjection, and were mixed with 100 μL of 6 mM EDTA (pH =5.0). The mixtures were centrifuged at a speed of 1500 rpm for 15 min. The supernatants were collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm Millex-LG syringe driven filter unit. The filtrates were analyzed by radio-HPLC (Method 2).

Statistical Analysis

Biodistribution data and target-to-background ratios are reported as an average plus the standard variation. Comparison between two different radiotracers was also made using the two-way ANOVA test (GraphPad Prism 4.0□GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

DTPA Conjugates

DTPA-Bn-SU016 was prepared by reacting E[c(RGDfK)]2 with excess p-SCN-Bn-DTPA in DMF under slightly basic conditions (pH = 8.0–9.0). The same procedure was used for preparation of DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016. All three conjugates were purified by HPLC with the purity >98% before being used for radiolabeling and animal studies. The ESI-MS data were completely consistent with the proposed formula for DTPA-Bn-SU016, DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016.

Integrin αvβ3 Binding Affinity

The integrin αvβ3 binding affinities of DTPA-Bn-SU016, DTPA-Bn-E-SU016, and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 were determined using the integrin αvβ3-positive U87MG human glioma cells. For comparison purposes, c(RGDyK) and SU016 were also evaluated in the same assay. Figure 2 shows the displacement curves of c(RGDyK), SU016, DTPA-Bn-SU016, DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 against the binding of 125I-c(RGDyK) to integrin αvβ3 on U87MG glioma cells. The IC50 values were calculated to be 31.9 ± 4.0 nM for c(RGDyK, 5.0 ± 0.7 nM for SU016, 7.9 ± 0.6 nM for DTPA-Bn-SU016, 5.8 ± 0.6 nM for DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 6.9 ± 0.9 nM for DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of 125I-c(RGDyK) binding to αvβ3 integrin on U87MG human glioma cells by c(RGDyK) (•), SU016 (■), DTPA-Bn-SU016 (○), DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 (△), and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 (×). IC50 values were calculated to be 31.9 ± 4.0 nM for c(RGDyK), 5.0 ± 0.7 nM for SU016, 7.9 ± 0.6 nM for DTPA-Bn-SU016, 5.8 ± 0.6 nM for DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 6.9 ± 0.9 nM for DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016, respectively.

Radiochemistry

111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 were prepared by reacting 111InCl3 with the DTPA conjugate in NH4OAc buffer (200 mM, pH = 5.5). Radiolabeling was almost instantaneous at room temperature, particularly at higher concentrations of the DTPA conjugate. Their radiochemical purity (RCP) was >99% after Sep-Pak purification. The specific activity was in the range of 100–150 mCi/μmole, which is consistent with that obtained for the 111In-labeled DTPA conjugate of a cyclic RGDfK monomer (40). The specific activity obtained at room temperature for all three 111In radiotracers in this study was 3–5 time better than that of the 111In-labeled DOTA conjugates (~30 mCi/μmole obtained at 100 °C) (33). It should be noted that the radiolabeling conditions used in this study are not optimized. The specific activity of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 could be further improved at elevated temperatures. All three 111In radiotracers were analyzed using the same HPLC method (Method 2). Their HPLC retention times were 18.2 min, 11.3 min and 11.7 min, respectively. Their log P values were determined in an equal volume mixture of n-octanol and 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4), and were calculated to be −2.7 ± 0.1 (n = 3), −3.4 ± 0.1 (n = 3) and −3.3 ± 0.2 (n = 3), respectively. Both HPLC retention time and log P values suggest that incorporation of E and Cys amino acid linkers increases hydrophilicity of the 111In-labeled cyclic RGDfK dimer.

Solution Stability

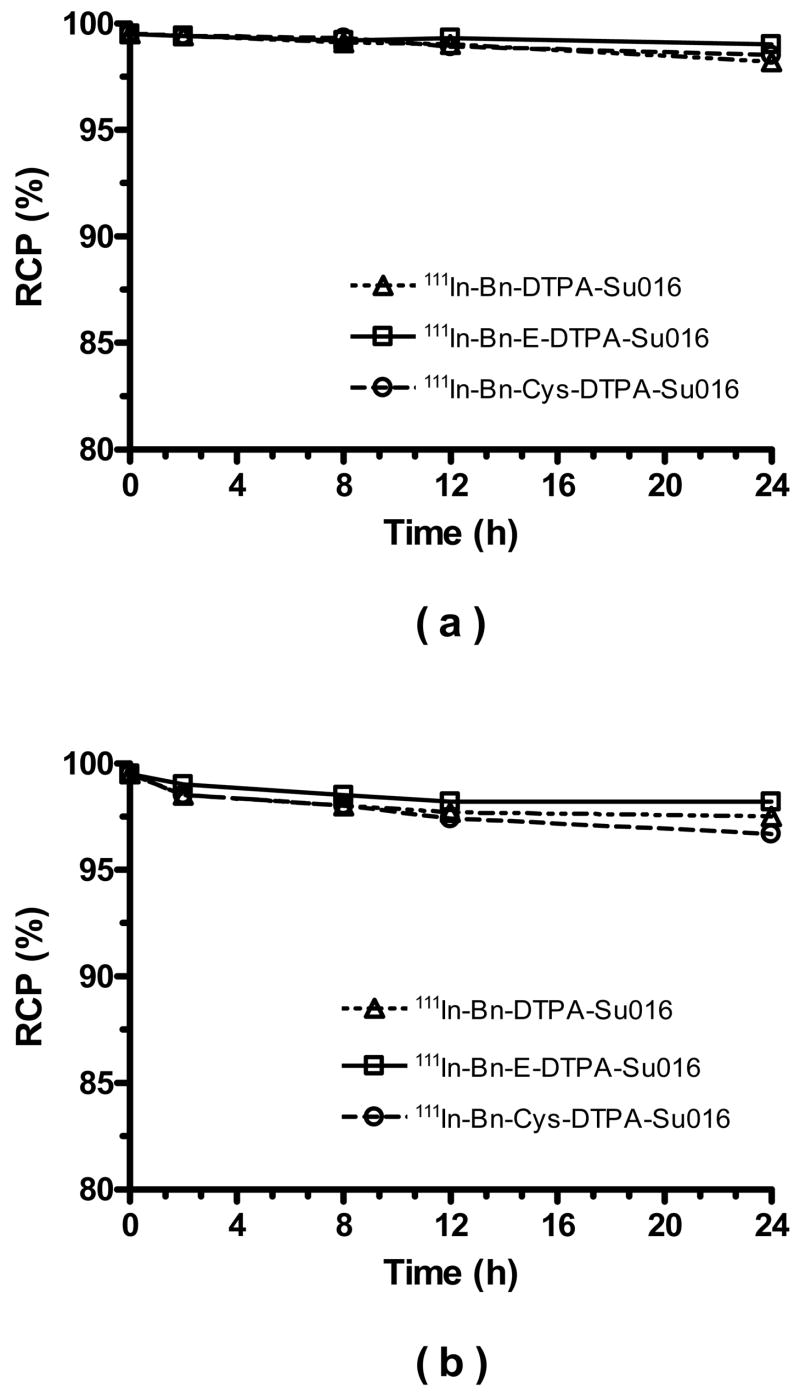

High solution stability is a requirement for both diagnostic and therapeutic radiotracers. In this study, we studied solution stability of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 both in saline and in the presence of EDTA challenge. Figure 3 shows their solution stability data in saline (a) and 6 mM EDTA solution (b). It was clear that all three 111In radiotracers remained stable for >24 h in saline and in aqueous solution of 6 mM EDTA.

Figure 3.

Solution stability data of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016, and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 in saline (a) and 6 mM EDTA solution (b).

Biodistribution Characteristics

Biodistribution properties of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 were evaluated using the BALB/c nude mice bearing the U87MG human glioma xenografts. Selected biodistribution data are listed in Tables 1–3. Figure 4 shows the comparison of excretion kinetics and T/B ratios between 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016. Since they share the same cyclic RGDfK dimer (SU016) and the 111In-DTPA chelate, their difference in biodistribution and excretion characteristics is caused by the linker (E and Cys).

Table 1.

Selected biodistribution data of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 in BALB/c nude mice bearing U87MG human glioma xenografts. The organ uptake is expressed %ID/g. Each data point represents an average of biodistribution data in four animals.

| Organ | 0.5 h | 1 h | 4 h | 24 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor | 2.53±0.63 | 2.21±0.65 | 1.86±0.34 | 1.69±0.18 |

| Blood | 0.69±0.02 | 0.22±0.04 | 0.09±0.06 | 0.05±0.02 |

| Heart | 1.07±0.09 | 0.95±0.40 | 0.49±0.05 | 0.43±0.09 |

| Liver | 2.48±0.22 | 2.49±0.38 | 2.86±0.53 | 1.93±0.28 |

| Spleen | 2.04±0.13 | 2.56±1.11 | 1.83±0.37 | 1.94±0.41 |

| Kidney | 9.07±1.29 | 7.34±0.70 | 7.05±1.49 | 6.14±1.34 |

| Muscle | 0.49±0.10 | 0.35±0.04 | 0.24±0.06 | 0.21±0.04 |

| Gut | 6.46±0.25 | 5.08±0.92 | 3.18±0.19 | 4.16±0.77 |

| Stomach | 3.88±0.39 | 2.86±0.15 | 1.78±0.15 | 1.55±0.24 |

| Bone | 0.93±0.07 | 0.76±0.14 | 0.52±0.23 | 0.51±0.11 |

Table 3.

Selected biodistribution data of 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 in BALB/c nude mice bearing U87MG human glioma xenografts. The organ uptake is expressed %ID/g. Each data point represents an average of biodistribution data in four animals.

| Organ | 0.5 h | 1 h | 4 h | 24 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor | 2.72±0.28 | 1.78±0.09 | 1.53±0.64 | 0.98±0.29 |

| Blood | 0.83±0.16 | 0.24±0.06 | 0.06±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 |

| Heart | 1.19±0.16 | 0.72±0.18 | 0.46±0.03 | 0.29±0.02 |

| Liver | 3.08±0.60 | 2.41±0.15 | 2.32±0.38 | 0.79±0.15 |

| Spleen | 2.08±0.19 | 1.74±0.62 | 1.58±0.11 | 1.08±0.24 |

| Kidney | 14.78±2.31 | 12.20±1.76 | 10.70±1.19 | 4.96±0.62 |

| Muscle | 0.57±0.04 | 0.37±0.05 | 0.23±0.03 | 0.14±0.02 |

| Gut | 7.09±0.86 | 5.03±0.81 | 3.48±0.44 | 3.41±0.82 |

| Stomach | 4.12±0.25 | 2.77±0.44 | 1.61±0.16 | 1.10±0.07 |

| Bone | 1.01±0.26 | 0.54±0.12 | 0.53±0.23 | 0.35±0.03 |

Figure 4.

Direct comparison of the excretion kinetics and tumor-to-background ratios between 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016, and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 in selected organs of the BALB/c nude mice bearing the U87MG human glioma xenografts.

In general, all three 111In radiotracers displayed a rapid blood clearance predominantly vial the renal route. Their blood clearance curves were almost identical (Figure 4), and their bone uptake was relatively low (Tables 1–3). The tumor uptake of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 was comparable between 0.5 h and 4 h p.i. within the experimental error. At 24 h p.i., however, 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 had the tumor uptake (1.69 ± 0.18 %ID/g) that was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 (0.89 ± 0.17 %ID/g) and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 (0.98 ± 0.29 %ID/g). The kidney uptake of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 was much lower (p < 0.001) than that of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 over the 24 h study period. The liver uptake of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 was comparable between 0.5 h and 1 h p.i. (Figure 4); but it was significantly higher (p < 0.001) for 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 than that for 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 at 24 h p.i. For example, the liver uptake of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 was 1.69 ± 0.18 %ID/g at 24 h p.i. and the liver uptake of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 was only 0.55 ± 0.11 %ID/g and 0.79 ± 0.15 %ID/g at 24 h p.i., respectively. Among the three 111In radiotracers evaluated in this animal model, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 has the lowest uptake in liver and kidneys, and the best tumor/liver and tumor/kidney ratios (Figure 4) at 24 h p.i.

The blocking experiment was used to demonstrate tumor-specificity of the radiotracer. In this experiment, E[c(RGDfK)]2 (15 mg/kg or ~300 μg/mouse) was used as the blocking agent. Such a high dose was used to make sure that the integrin αvβ3 is almost completely blocked. Figure 5 illustrates biodistribution data of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 at 4 h p.i. in the presence of E[c(RGDfK)]2. Apparently, pre-injection of excess E[c(RGDfK)]2 significantly reduced the tumor uptake of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016, suggesting that its tumor uptake is indeed integrin αvβ3-mediated. However, its uptake in liver, spleen, stomach, guts and kidneys, was also reduced significantly, most likely due to the blockage of integrin αvβ3 in these organs.

Figure 5.

Biodistribution data of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 at 4 h p.i. with/without the presence of excess E[c(EGDfK)]2 in BALB/c nude mice bearing the U87MG human glioma xenografts.

Metabolism

Metabolism studies on 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 were performed using normal BALB/c nude mice. Urine samples were analyzed to determine if they are able to retain their chemical integrity at 1 h p.i. We also tried to analyze feces samples at 1 h p.i., but the radioactivity level was too low to be detected. Figure 6 shows HPLC chromatograms of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 in the urine at 1 h p.i. It is quite clear that there is little metabolite (<10%) in urine during the 1 h study period.

Figure 6.

Radio-HPLC chromatograms of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 (top), 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 (middle), and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016) (bottom) in the kit matrix and urine at 1 h p.i. Each normal BALB/c mouse was administered with 200 μCi of radiotracer. Two mice were used for each radiotracer.

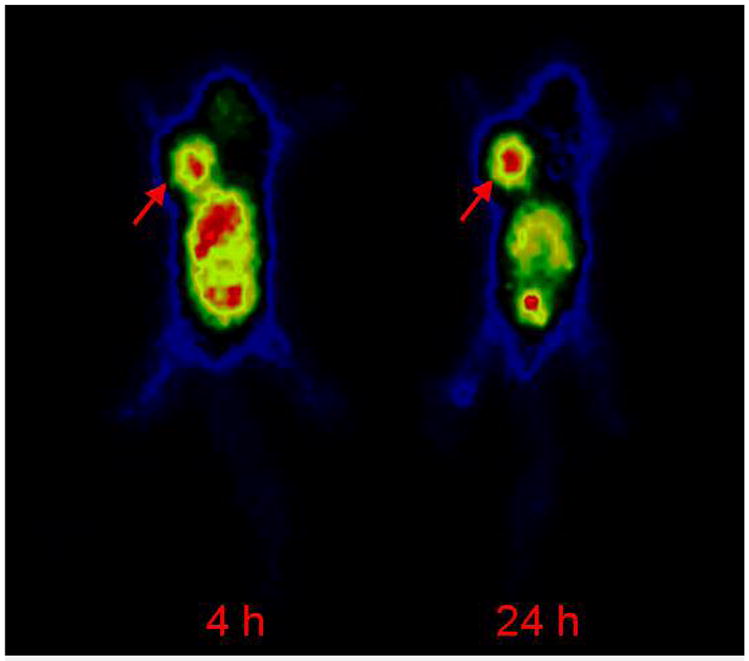

Imaging Study

A planar image study was performed on 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 using the BALB/c nude mice bearing U87MG human glioma xenografts. Figure 7 illustrates representative scintigraphic images of the tumor-bearing mouse administered with ~ 200 μCi 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 at 4 h and 24 h p.i. The tumor was visualized as early as 1 h p.i. (data not shown). The tumor/muscle ratio was 5.6 ± 1.2 (n = 3) at 4 h p.i. and 6.1 ± 1.1 (n = 3) at 24 h p.i., which were in good agreement with that obtained from direct tissue sampling (Tables 1–3). Because of high kidney and liver activity, the tumor/kidney and tumor/liver ratios were relatively low (0.4 ± 0.1 and 1.0 ± 0.1 at 4 h, 1.9 ± 0.4 and 2.3 ± 0.3 at 24 h, respectively).

Figure 7.

A representative scintigraphic image of the tumor-bearing mouse administered with ~200 μCi of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016. The arrow indicates presence of tumor.

DISCUSSION

Many factors may influence the tumor uptake and tumor retention of a radiotracer (13–15). These include binding affinity, receptor population, protein binding, and pharmacokinetics. The fact that [18F]Galacto-RGD has been successfully used as the first PET radiotracer for noninvasive visualization of integrin αvβ3 in cancer patients strongly suggests that there are sufficient integrin αvβ3 expressed in tumor for PET or SPECT imaging. While the radiolabeled cyclic RGD peptide monomers, such as c(RGDfK), are useful for imaging the integrin αvβ3 expression in tumors, they will have limited clinical utility in visualizing tumors in the lower abdomen region due to their relatively low tumor uptake and partial hepatobiliary excretion. Therefore, there is a continuing need to further improve the tumor targeting capability and excretion kinetics of radiotracers.

To improve integrin αvβ3 binding affinity, the multivalent concept has been successfully used to prepare multimeric cyclic RGD peptides, such as E[c(RGDfK)]2 and E{E[c(RGDfK)]2}2, for development of the integrin αvβ3-targeted diagnostic (64Cu, 99mTc and 111In) and therapeutic (90Y and 177Lu) radiotracers (19–36). Different PKM linkers have been used to improve excretion kinetics of the radiolabeled peptides. For example, a sugar moiety was used to increase T/B ratios of 125I and 18F-labeled cyclic RGD peptides (47–50). The sugar moiety has also been used to improve tumor uptake and TB ratios of the 111In-labeled DOTA-somatostatin peptide conjugates (51). Small peptides, such as di(cysteic acid), have been used to improve blood clearance and to minimize liver accumulation of radiolabeled peptides and nonpeptide integrin αvβ3 antagonists (38, 52–54). It has been reported that introduction of the polyethylene glycol (PEG) linker can improve not only tumor uptake but also excretion kinetics of 125I and 18F-labeled c(RGDyK) and 64Cu-labeled E[c(RGDyK)]2 (55, 56). PEG4 and amino acid linkers, such as E and K, have also been used to improve excretion kinetics of 111In and 99mTc-labeled E[c(RGDfK)]2 (23, 33). PKM linkers and their applications to improve excretion kinetics of radiolabeled small biomolecules have been reviewed recently (15, 16, 37).

In this study, we prepare 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 with high specific activity (100–150 mCi/μmole). We are particularly interested in DTPA as the BFC because of its high 111In-labeling efficiency. The specific activity obtained for these three 111In radiotracers was 3–5 time better than that of the111In-labeled DOTA-PKM-E[c(RGDfK)]2 (PKM = E, K and PEG4) conjugates (33). We also examined the effect of E and Cys linkers on integrin αvβ3 binding affinity of the cyclic RGDfK dimer DTPA conjugate, and found that the integrin αvβ3 binding affinity of DTPA-Bn-SU016, DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 was almost identical. This suggests that introduction of the E and Cys linker does not affect the integrin αvβ3 binding affinity of E[c(RGDfK)]2. Similar conclusion has been made for the HYNIC and DOTA conjugates of E[c(RGDfK)]2 (23).

The main difference between 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 is the linker group. Both HPLC and log P data suggest that the use of E and Cys linker groups increases hydrophilicity of the 111In radiotracer. The tumor targeting capability of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 has been evaluated by direct tissue sampling and gamma imaging in BALB/c nude mice bearing U87MG human glioma xenografts. Results from biodistribution studies show that there is no significant difference in their tumor uptake during the first 4 h p.i. (Figure 5), suggesting that E and Cys linkers have little impact on targeting capability of the 111In-labeled E[c(RGDfK)]2. This conclusion is supported by similar integrin αvβ3 binding affinity of SU016, DTPA-Bn-SU016, DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 (Figure 2). The blood clearance patterns of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 are almost identical over the 24 h study period, indicating that introduction of E and Cys linkers did not significantly affect their protein binding. In addition, 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 are also able to retain their chemical integrity with <10% metabolism detected in the urine samples at 1 h p.i. The fact that very little radioactivity was detected in feces samples from the mice administered with 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 suggest that they are excreted mainly via the renal route.

Despite their similarities, E and Cys linkers have a significant impact on organ uptake and excretion kinetics of the 111In-labeled cyclic RGDfK dimer. For example, the kidney uptake follows the order of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 < 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 < 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 (Figure 5). The tumor/kidney ratios of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 are significantly lower (p < 0.05) than that of 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 at 24 h p.i. In general, small biomolecules in the blood plasma are filtered through glomerular capillaries in kidneys and may be subsequently reabsorbed by the proximal tubular cells (33). Membranes of renal tubular cells contain negatively charged sites to which the positively charged groups (such as guanidine in the RGD sequence) are expected to bind. The carboxylic group of the glutamic acid residue is deprotonated under physiological conditions. Therefore, it is not surprising that the use of E linker in 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 results in the reduced kidney uptake (Figure 5). However, it is not clear why 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 has higher kidney uptake than 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 even though their log P value and HPLC retention times (Figure 6) are very similar.

Another significant difference is the liver uptake. Both 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016 have lower liver uptake and better tumor/liver ratios (p < 0.05) than 111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016 at 24 h p.i. These data strongly suggest that the liver uptake could be reduced by introducing the negatively charged amino acid residues due to increased hydrophilicity of the radiotracer. Similar conclusion has been made for the 99mTc-labeled HYNIC-PKM-SU016 (PKM = E, K or PEG4) conjugates (23). However, this conclusion seems to contradict to that made by Dijkgraaf and coworkers (33) for the 111In-labeled DOTA-PKM-E[c(RGDfK)]2 (PKM = E, K and PEG4) conjugates. Apparently, the impact of PKM linkers on both liver uptake and liver clearance kinetics of the radiotracer may vary with the change of bifunctional chelator and its radiometal chelate.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we evaluated the integrin αvβ3 binding affinities of SU016, DTPA-Bn-SU016, DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016. It was found that introduction of the glutamic acid and cysteic acid linkers did not affect the integrin αvβ3 binding affinity of the cyclic RGDfK dimer DTPA conjugate. Another important finding of this study is that the 111In-labeling efficiency of all three DTPA conjugates (DTPA-Bn-SU016, DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016) is significantly better than that of DOTA analogs. In this regard, DTPA has the advantage over DOTA due to its fast chelation kinetics and high-yield 111In-labeling under mild conditions (e.g. room temperature). All three radiotracers (111In-DTPA-Bn-SU016, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 and 111In-DTPA-Bn-Cys-SU016) have high in vitro and in vivo solution stability. Results from biodistribution studies show that incorporation of the glutamic acid linker between DTPA and E[c(RGDfK)]2 increases the clearance of 111In-labeled E[c(RGDfK)]2 from the liver and kidneys. Among the three radiotracers evaluated in this study, 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 has the best tumor/liver and tumor/kidney ratios.

Table 2.

Selected biodistribution data of 111In-DTPA-Bn-E-SU016 in BALB/c nude mice bearing U87MG human glioma xenografts. The organ uptake is expressed %ID/g. Each data point represents an average of biodistribution data in four animals.

| Organ | 0.5 h | 1 h | 4 h | 24 h | 4.0 h/Block |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor | 2.45±0.43 | 2.33±0.55 | 1.86±0.15 | 0.89±0.17 | 0.25±0.06 |

| Blood | 0.71±0.10 | 0.21±0.07 | 0.06±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.04±0.01 |

| Heart | 1.06±0.14 | 0.72±0.10 | 0.47±0.05 | 0.20±0.04 | 0.06±0.00 |

| Liver | 2.94±0.38 | 3.12±0.38 | 2.15±0.09 | 0.55±0.11 | 0.29±0.04 |

| Spleen | 2.13±0.26 | 2.01±0.43 | 1.60±0.22 | 0.79±0.25 | 0.18±0.03 |

| Kidney | 6.04±1.40 | 5.29±0.51 | 3.80±0.33 | 1.37±0.16 | 2.58±0.42 |

| Muscle | 0.52±0.06 | 0.37±0.06 | 0.22±0.03 | 0.12±0.02 | 0.04±0.00 |

| Gut | 5.36±1.98 | 5.36±0.49 | 4.31±0.52 | 1.73±0.22 | 0.40±0.09 |

| Stomach | 3.92±0.28 | 3.00±0.30 | 1.64±0.11 | 0.70±0.06 | 0.22±0.07 |

| Bone | 0.97±0.20 | 0.77±0.23 | 0.40±0.08 | 0.34±0.04 | 0.08±0.02 |

Acknowledgments

Authors would thank Professor Jingde Zhu, Shanghai Cancer Research Institute, for providing the U87MG human glioma cells. This work is supported, in part, by Peking University Health Science Center (F.W.) and research grants: 30640067 (F.W.) from NSF (China), 1R01 CA115883-01A2 (S.L.) from National Cancer Institute (NCI), BCTR0503947 (S.L.) from Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, AHA0555659Z (S.L.) from the Greater Midwest Affiliate of American Heart Association, R21 EB003419-02 (S.L.) from National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) and R21 HL083961-01 (S.L.) from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

References

- 1.Folkman J. Fundamental concepts of the angiogenic process. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:643–651. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin H, Varner J. Integrins: roles in cancer development and as treatment targets. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:561–565. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howe A, Aplin AE, Alahari SK, Juliano RL. Integrin signaling and cell growth control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:220–231. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longhurst CM, Jennings LK. Integrin-mediated signal transduction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:514–526. doi: 10.1007/s000180050180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zitzmann S, Ehemann V, Schwab M. Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic acid (RGD)-peptide binds to both tumor and tumor endothelial cells in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5139–5143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber WA, Haubner R, Vabuliene E, Kuhnast B, Webster HJ, Schwaiger M. Tumor angiogenesis targeting using imaging agents. Q J Nucl Med. 2001;45:179–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van de Wiele C, Oltenfreiter R, De Winter O, Signore A, Slegers G, Dierckx RA. Tumor angiogenesis pathways: related clinical issues and implications for nuclear medicine imaging. Eur J Nucl Med. 2002;29:699–709. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0783-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McQuade P, Knight LC. Radiopharmaceuticals for targeting the angiogenesis marker αvβ3. Q J Nucl Med. 2003;47:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haubner RH, Wester HJ, Weber WA, Schwaiger M. Radiotracer-based strategies to image angiogenesis. Q J Nucl Med. 2003;47:189–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haubner R, Kuhnast B, Mang C, Weber WA, Kessler H, Wester HJ, Schwaiger M. [18F]Galacto-RGD: synthesis, radiolabeling, metabolic stability, and radiation dose estimates. Bioconj Chem. 2004;15:61–69. doi: 10.1021/bc034170n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beer AJ, Haubner R, Goebel M, Luderschmidt S, Spilker ME, Webster HJ, Weber WA, Schwaiger M. Biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of the αvβ3-selective tracer 18F-Galacto-RGD in cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1333–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haubner R, Weber WA, Beer AJ, Vabuliene E, Reim D, Sarbia M, Becker KF, Goebel M, Hein R, Wester HJ, Kessler H, Schwaiger M. Noninvasive visuallization of the activiated αvβ3 integrin in cancer patients by positron emission tomography and [18F]Galacto-RGD. PLOS Med. 2005;2:e70, 244–252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Robinson SP, Edwards DS. Integrin αvβ3 directed radiopharmaceuticals for tumor imaging. Drugs of the Future. 2003;28:551–564. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S, Robinson SP, Edwards DS. Radiolabeled integrin αvβ3 antagonists as radiopharmaceuticals for tumor radiotherapy. Topics in Curr Chem. 2005;252:193–216. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S. Radiolabeled multimeric cyclic RGD peptides as integrin αvβ3-targeted radiotracers for tumor imaging. Mol Pharm. 2006;3:472–487. doi: 10.1021/mp060049x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haubner R, Wester HJ. Radiolabeled tracers for imaging of tumor angiogenesis and evaluation of anti-angiogenic therapies. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:1439–1455. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wester HJ, Kessler H. Molecular targeting with peptides or peptide-polymer conjugates: just a question of size? J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1940–1945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X. Multimodality imaging of tumor integrin αvβ3 expression. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2006;6:227–234. doi: 10.2174/138955706775475975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Edwards DS, Ziegler MC, Harris AR, Hemingway SJ, Barrett JA. 99mTc-Labeling of a hydrazinonicotinamide-conjugated vitronectin receptor antagonist useful for imaging tumors. Bioconj Chem. 2001;12:624–629. doi: 10.1021/bc010012p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S, Cheung E, Rajopadhye M, Ziegler MC, Edwards DS. 90Y- and 177Lu-labeling of a DOTA-conjugated vitronectin receptor antagonist useful for tumor therapy. Bioconj Chem. 2001;12:559–568. doi: 10.1021/bc000146n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S, Hsieh WY, Kim YS, Mohammed SI. Effect of coligands on biodistribution characteristics of ternary ligand 99mTc complexes of a HYNIC-conjugated cyclic RGDfK dimer. Bioconj Chem. 2005;16:1580–1588. doi: 10.1021/bc0501653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia B, Shi J, Yang Z, Xu B, Liu Z, Zhao H, Liu S, Wang F. 99mTc-labeled cyclic RGDfK dimer: initial evaluation for SPECT imaging of glioma integrin αvβ3 expression. Bioconj Chem. 2006;17:1069–1076. doi: 10.1021/bc060055b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S, He ZJ, Hsieh WY, Kim YS, Jiang Y. Impact of PKM linkers on biodistribution characteristics of the 99mTc-labeled cyclic RGDfK dimer. Bioconj Chem. 2006;17:1499–1507. doi: 10.1021/bc060235l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Hsieh WY, Jiang Y, Kim YS, Sreerama SG, Chen X, Jia B, Wang F. Evaluation of a 99mTc-labeled cyclic RGD tetramer for noninvasive imaging integrin αvβ3-positive breast cancer. Bioconj Chem. 2007;18:438–446. doi: 10.1021/bc0603081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu S, Kim YS, Hsieh WY, Sreerama SG. Coligand effects on solution stability, biodistribution and metabolism of 99mTc-labeled cyclic RGDfK tetramer. Nucl Med Biol ASAP. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Liu S, Hou Y, Tohme M, Park R, Bading JR, Conti PS. MicroPET Imaging of Breast Cancer αv-Integrin Expression with 64Cu-Labeled Dimeric RGD Peptides. Mol Imag Biol. 2004;6:350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen X, Park R, Tohme M, Shahinian AH, Bading JR, Conti PS. MicroPET and autoradiographic imaging of breast cancer αv-integrin expression using 18F- and 64Cu-labeled RGD peptide. Bioconj Chem. 2004;15:41–49. doi: 10.1021/bc0300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen X, Park R, Hou Y, Khankaldyyan V, Gonzales-Gomez I, Tohme M, Bading JR, Laug WE, Conti PS. MicroPET imaging of brain tumor angiogenesis with 18F-labeled PEGylated RGD peptide. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:1081–1089. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Y, Zhang X, Xiong Z, Cheng Z, Fisher DR, Liu S, Gambhir SS, Chen X. MicroPET imaging of glioma αvβ3 integrin expression using 64Cu-labeled tetrameric RGD peptide. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1707–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Xiong Z, Wu Y, Cai W, Tseng JR, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Quantitative PET imaging of tumor integrin αvβ3 expression with 18F-FRGD2. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:113–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janssen ML, Oyen WJG, Dijkgraaf I, Massuger LFAG, Frielink C, Edwards DS, Rajopadyhe M, Boonstra H, Corsten FH, Boerman OC. Tumor targeting with radiolabeled αvβ3 integrin binding peptides in a nude mouse model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6146–6151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janssen ML, Frielink C, Dijkgraaf I, Oyen WJ, Edwards DS, Liu S, Rajopadhye M, Massuger LF, Corstens FH, Boerman OC. Improved tumor targeting of radiolabeled RGD-peptides using rapid dose fractionation. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2004;19:399–404. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2004.19.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dijkgraaf I, Liu S, Kruijtzer JAW, Soede AC, Oyen WJG, Liskamp RMJ, Corstens FHM, Boerman OC. Effect of linker variation on the in vitro and in vivo characteristics of an 111In-labeled RGD Peptide. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dijkgraaf I, John AW, Kruijtzer JAW, Liu S, Soede A, Oyen WJG, Corstens FHM, Liskamp RMJ, Boerman OC. Improved targeting of the αvβ3 integrin by multimerization of RGD peptides. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:267–273. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poethko T, Schottelius M, Thumshirn G, Herz M, Haubner R, Henriksen G, Kessler H, Schwaiger M, Wester HJ. Chemoselective pre-conjugate radiohalogenation of unprotected mono- and multimeric peptides via oxime formation. Radiochim Acta. 2004;92:317–327. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thumshirn G, Hersel U, Goodman SL, Kessler H. Multimeric cyclic RGD peptides as potential tools for tumor targeting: solid-phase peptide synthesis and chemoselective oxime ligation. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:2717–2725. doi: 10.1002/chem.200204304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu S, Edwards DS. Bifunctional chelators for therapeutic lanthanide radiopharmaceuticals. Bioconj Chem. 2001;12:7–34. doi: 10.1021/bc000070v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Onthank DC, Liu S, Silva PJ, Barrett JA, Harris TD, Robinson SP, Edwards DS. 90Y and 111In complexes of A DOTA-conjugated integrin αvβ3 receptor antagonist: different but biologically equivalent. Bioconj Chem. 2004;15:235–241. doi: 10.1021/bc034108q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S, Cheung E, Rajopadhye M, Williams NE, Overoye KL, Edwards DS. Isomerism and solution dynamics of 90Y-labeled DTPA-biomolecule conjugates. Bioconj Chem. 2001;12:84–91. doi: 10.1021/bc000071n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu S, Edwards DS. Synthesis and characterization of two 111In-labeled DTPA-peptide conjugates. Bioconj Chem. 2001;12:630–634. doi: 10.1021/bc010013h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camera L, Kinuya S, Garmestani K, Wu C, Brechbiel MW, Pai LH, McMurry TJ, Gansow OA, Pastan I, Paik CH, Carrasquillo JA. Evaluation of the serum stability and in vivo biodistribution of CHX-DTPA and other ligands for yttrium labeling of monoclonal antibodies. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:882–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMurray TJ, Pippin CG, Wu C, Deal KA, Brechbiel MW, Mirzadeh S, Gansow OA. Physical parameters and biological stability of yttrium(III) diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid derivative conjugates. J Med Chem. 1998;41:3546–3549. doi: 10.1021/jm980152t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carrasquillo JA, White JD, Paik CH, Raubitschek A, Le N, Rotman M, Brechbiel MW, Gansow OA, Top LE, Perentesis P, Reynolds JC, Nelson DL, Waldmann TA. Similarities and differences in 111In- and 90Y-labeled 1B4M-DTPA antiTac monoclonal antibody distribution. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:268–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camera L, Kinuya S, Garmestani K, Brechbiel MW, Wu C, Pai LH, McMurry TJ, Gansow OA, Pastan I, Paik CH, Carrasquillo JA. Comparative biodistribution of indium- and yttrium-labeled B3 monoalonal antibody conjugated to either 2-(p-SCN-Bz)-6-methyl-DTPA (1B4M-DTPA) or 2-(p-SCN-Bz-)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane tetraacetic acid (2B-DOTA) Eur J Nucl Med. 1994;21:640–646. doi: 10.1007/BF00285586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith-Jones PM, Stolz B, Albert R, Ruser G, Briner U, Mäcke HR, Bruns C. Synthesis and characterization of [90Y]-Bz-DTPA-oct: a yttrium-90-labelled octreotide analogue for radiotherapy of somatostatin receptor-positive tumors. Nucl Med Biol. 1998;25:181–188. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Jong M, Bernard BF, De Bruin E, Van Gameren A, Bakker WH, Visser TJ, Mäcke HR, Krenning EP. Internalization of radiolabelled [DTPAo]octreotide and [DOTAo, Tyr3]octreotide: peptides for somatostatin receptor-targeted scintigraphy and radionuclide therapy. Nucl Med Commun. 1998;19:283–288. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199803000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haubner R, Wester HJ, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Diefenbach B, Kessler H, Stöcklin G, Schwaiger M. RGD-peptides for tumor targeting: biological evaluation of radioiodinated analogs and introduction of a novel glycosylated peptide with improved biokinetics. J Labelled Compounds & Radiopharmaceuticals. 1997;40:383–385. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haubner R, Wester HJ, Reuning U, Senekowisch-Schmidtke R, Diefenbach B, Kessler H, Stöcklin G, Schwaiger M. Radiolabeled αvβ3 integrin antagonists: a new class of tracers for tumor imaging. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1061–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haubner R, Wester HJ, Burkhart F, Senekowisch-Schmidtke R, Weber W, Goodman SL, Kessler H, Schwaiger M. Glycolated RGD-containing peptides: tracer for tumor targeting and angiogenesis imaging with improved biokinetics. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:326–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haubner R, Wester HJ, Weber WA, Mang C, Ziegler SI, Goodman SL, Senekowisch-Schmidtke R, Kessler H, Schwaiger M. Noninvasive imaging of αvβ3 integrin expression using 18F-labeled RGD-containing glycopeptide and positron emission tomography. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1781–1785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antunes P, Ginj M, Walter MA, Chen J, Reubi JC, Maecke HR. Influence of different spacers on biological profile of a DOTA-Somatostatin Analogue. Bioconj Chem. 2007;18:84–92. doi: 10.1021/bc0601673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harris TD, Kalogeropoulos S, Nguyen T, Liu S, Bartis J, Ellars CE, Edwards DS, Onthanks D, Yalamanchili P, Robinson SP, Lazewatsky J, Barrett JA. Design, synthesis and evaluation of radiolabeled integrin αvβ3 antagonists for tumor imaging and radiotherapy. Cancer Biotherapy & Radiopharmaceuticals. 2003;18:627–641. doi: 10.1089/108497803322287727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris TD, Kalogeropoulos S, Nguyen T, Dwyer G, Edwards DS, Liu S, Bartis J, Ellars C, Onthank D, Yalamanchili P, Heminway S, Robinson S, Lazewatsky J, Barrett JA. Structure-activity relationships of 111In- and 99mTc-labeled quinolin-4-one peptidomimetics as ligands for the vitronectin receptor: potential tumor imaging agents. Bioconj Chem. 2006;17:1294–1313. doi: 10.1021/bc060063s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris TD, Cheesman E, Harris AR, Sachleben R, Edwards DS, Liu S, Bartis J, Ellars C, Onthank D, Yalamanchili P, Heminway S, Silva P, Robinson S, Lazewatsky J, Rajopadhye M, Barrett JA. Radiolabeled divalent peptidomimetic vitronectin receptor antagonists as potential tumor radiotherapeutic and imaging Agents. Bioconj Chem. 2007;18:1266–1279. doi: 10.1021/bc070002+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen X, Park R, Shahinian AH, Bading JR, Conti PS. Pharmacokinetics and tumor retention of 125I-labeled RGD peptide are improved by PEGylation. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen X, Sievers E, Hou Y, Park R, Tohme M, Bart R, Bremner R, Bading JR, Conti PS. Integrin αvβ3–targeted imaging of lung cancer. Neoplasia. 2005;7:271–279. doi: 10.1593/neo.04538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]