Summary

Most homeodomains are unique within a genome, yet many are highly conserved across vast evolutionary distances, implying strong selection on their precise DNA-binding specificities. We determined the binding preferences of the majority (168) of mouse homeodomains to all possible 8-base sequences, revealing rich and complex patterns of sequence specificity, and showing for the first time that there are at least 65 distinct homeodomain DNA-binding activities. We developed a computational system that successfully predicts binding sites for homeodomain proteins as distant from mouse as Drosophila and C. elegans, and we infer full 8-mer binding profiles for the majority of known animal homeodomains. Our results provide an unprecedented level of resolution in the analysis of this simple domain structure and suggest that variation in sequence recognition may be a factor in its functional diversity and evolutionary success.

Introduction

The ~60 amino acid homeobox domain or ‘homeodomain’ is a conserved DNA-binding protein domain best known for its role in transcription regulation during vertebrate development. The homeodomain can both bind DNA and mediate protein-protein interactions (Wolberger, 1996); however, the precise mechanisms that dictate the physiological function and target range of individual homeodomain proteins are in general either unknown or incompletely delineated (Banerjee-Basu et al., 2003; Svingen and Tonissen, 2006). In several cases, functional specificity can be traced to the homeodomain itself (Chan and Mann, 1993; Furukubo-Tokunaga et al., 1993; Lin and McGinnis, 1992), indicating that individual homeodomains have distinct protein- and/or DNA-binding activities. Since many homeodomains have similar DNA sequence preferences, much attention has been paid to the role of protein-protein interactions in target definition (Svingen and Tonissen, 2006), despite evidence that the sequence specificity of monomers contributes to targeting specificity (Ekker et al., 1992) and that binding sequences do vary, particularly among different subtypes (Banerjee-Basu et al., 2003; Ekker et al., 1994; Sandelin et al., 2004). Indeed, it has been proposed that the DNA binding specificity of homeodomains is determined by a combinatorial molecular code among the DNA-contacting residues (Damante et al., 1996).

Efforts to understand the physiological and biochemical functions of homeodomains have been hindered by the fact that most have only a few known binding sequences, if any. Position weight matrices (PWMs) have been compiled for 63 distinct homeodomain-containing proteins from human, mouse, D. melanogaster, and S. cerevisiae in the JASPAR (Bryne et al., 2008) and TRANSFAC (Matys et al., 2003) databases. These matrices are based on 5 to 138 individual sequences (median 18), presumably capturing only a subset of the permissible range of binding sites for these factors. Further, the accuracy of PWM models has been questioned (Benos et al., 2002), and there are many examples in which transcription factors bind sets of sequences that cannot be described in a conventional PWM representation (Blackwell et al., 1993; Chen and Schwartz, 1995; Overdier et al., 1994).

Moreover, the sequence preferences of the individual proteins can, in some cases, be altered by the binding context: for instance, the binding specificity of the complex of Drosophila Hox-Exd homeodomain proteins is remarkably different from that of the individual monomers (Joshi et al., 2007), raising the prospect that the monomeric binding preferences may not always be relevant to targeting in vivo. There is evidence that the sequence preferences of individual Hox proteins in Drosophila and mammals are significantly altered by physical interactions with protein co-factors in the PBC and Meis subfamilies, presumably through contacts to the Hox N-terminal arm that change the way the homeodomain contacts DNA (Mann and Chan, 1996; Wilson and Desplan, 1999). Other evidence, however, suggests that these examples of co-factor alterations to the monomer binding specificities are likely to be the exception rather than the rule. Carr and Biggin demonstrated that there is good correlation between monomer binding in vitro and in vivo for four fly homeodomain-containing proteins: Eve, Ftz, Bcd, and Prd (Carr and Biggin, 1999). Carroll and colleagues further showed that Ubx activity in promoting haltere development is independent of protein co-factors and that the promoters of its target genes in this pathway contain clusters of individual Ubx binding sites (Galant et al., 2002). Liberzon et al., showed not only that the specificity of the Hox-like mouse protein Pdx1 also extends beyond the TAAT core, but that the preferences at these flanking positions in vitro correlate with the ability of these sequences to stimulate transcription in vivo (Liberzon et al., 2004). In addition, for many domain classes, and in organisms ranging from yeast to human, in vivo binding sites detected by ChIP-chip typically contain sequences that reflect those preferred in vitro (Carroll et al., 2005; Harbison et al., 2004).

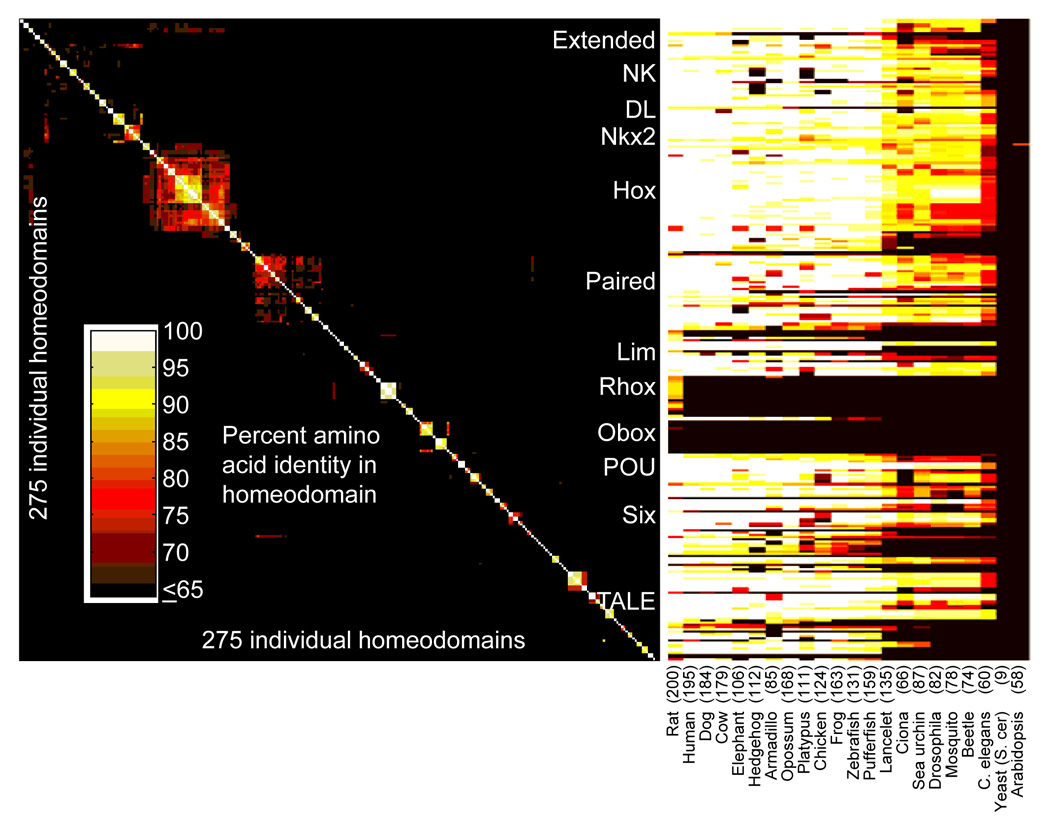

The mouse genome encodes a larger number of homeodomains than most vertebrates, including humans, and contains representatives of both ancient (NK, Hox) and young (Rhox, Obox) homeodomain families, encompassing striking examples of both purifying and diversifying selection (Jackson et al., 2006; Larroux et al., 2007; Rajkovic et al., 2002). The mouse homeodomain complement, estimated at 260 distinct proteins and 275 individual homeodomains (Bult et al., 2004), is broadly conserved across animals (Fig. 1). For example, most mouse homeodomains (172/275 or 63%) have an identical human counterpart, and among these, most (107/172) have fewer than ten amino acid differences from their Drosophila counterpart. In contrast to their relative invariance over evolutionary time, however, most homeodomains within a genome are very different from other homeodomains within the same genome (Fig. 1): although there are 22 instances of mouse proteins with identical homeodomains, the median number of amino acid differences between any two mouse homeodomains is 37.

Figure 1. Heat-map showing the number of mismatches between different hierarchically clustered mouse homeodomains (left) and their closest BLAST or BLAT hit in other species as indicated (right).

The number of distinct homeodomain-containing protein counterparts in other species is given, based on the number of different gene sequences represented (i.e., isoforms are counted as a single entity). Major homeodomain families are indicated.

In this analysis, we sought to fully characterize the sequence preferences of mouse homeodomains in order to ask whether the binding activity is unique to each homeodomain and whether the full activity profile can be predicted from the primary amino acid sequence of the homeodomain, in a way consistent with a molecular code. We also explore the relevance of the monomeric binding preferences to binding sites in vivo. Since the mouse homeodomains exemplify the functional diversity inherited from the common ancestor of all animals, as well as the potential for homeodomain expansion and divergence, our results and conclusions are extendible across the animal kingdom.

Results

Analysis of the Binding Preferences of Mouse Homeodomains to All 8-mers

Structures of homeodomains binding to DNA, as well as in vivo and in vitro selected binding sequences, are consistent with a typical binding footprint of seven or eight bases for a homeodomain monomer (Banerjee-Basu et al., 2003; Sandelin et al., 2004). To analyze the DNA-binding specificity, we used protein binding microarrays (PBMs) (Mukherjee et al., 2004) containing 41,944 60-mer probes in which all possible 10-base sequences are represented. Moreover, all non-palindromic 8-mers occur on at least 32 spots on our microarray in different sequence contexts, thus providing a robust estimate of the binding preference of each protein to all 8-mers (Berger et al., 2006). To facilitate inference of wider motifs, the arrays also contain 32 instances of all gapped 8-mers up to a width of 12 bases. In total, we can reliably derive quantitative binding data for 22.3 million gapped and contiguous 8-mers (48 sequence variants of 341 patterns up to 8-of-12) for any single protein. We used PBMs to analyze 194 of the 260 mouse homeodomain proteins for which we were able to produce protein as T7-driven, GST-tagged constructs by either in vitro transcription/translation or expression and purification from E. coli.

We systematically quantified the relative preference of each homeodomain for all possible 8-mers by several measures. These data, together with the raw microarray intensities, are posted as Supplementary Online Data. The median normalized signal intensity from each 8-mer (and its Z-score transform) scale almost linearly with Ka, when known (Berger et al., 2006), but may be sensitive to the amount of protein used in the assay (data not shown). We can additionally express the binding specificity of each protein as a mononucleotide position weight matrix (PWM), or motif (contained in Supplementary Table 1), but these often fail to fully capture the complete spectrum of binding activities and lack the resolution provided by individual word-by-word measurements (Benos et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2007). Here, we primarily employ a statistic we refer to as the E (enrichment) score for each 8-mer, which is a variation on AUC (Area under the ROC curve) and scales from 0.5 (highest) to −0.5 (lowest) (Berger et al., 2006). This measure is unitless and has a nonlinear scaling with intensity (there is a compression of the dynamic range among the most highly-bound sequences), but on the basis of rank correlations and precision/recall analysis it is the most highly reproducible of any measure we have tested (Supplementary Figure 3), and it facilitates comparison between separate experiments. On the basis of random permutations of the array data, our entire data set should contain no randomly-arising E-scores above 0.45. Using E > 0.45 for at least one 8-mer as a PBM success criterion, we obtained clear sequence preferences for 168 homeodomain proteins, including 11 different factors with identical homeodomain amino acid sequences. On average, each homeodomain had 144 such ungapped preferred 8-mers. It is possible that some proteins for which no sequence preference was obtained were improperly folded. The 26 we scored as unsuccessful, however, include 7 of the 9 Rhox isoforms tested, all 3 of the Lass isoforms tested, and both Satb isoforms tested, suggesting that these classes bind DNA non-specifically or not at all, or require modifications or co-factors not present in these experiments. This conclusion is supported by previous observations that Satb1 (Special A-T-rich binding protein 1) binding preferences relate primarily to nucleotide composition and not to a specific sequence (Dickinson et al., 1992), a trend which is also present in our data (data not shown). Each of these 12 proteins exhibits a non-consensus amino acid in at least one of the four positions conserved across nearly all homeodomains (positions 48, 49, 51, 53 (Banerjee-Basu et al., 2003)), as do the majority of all failures that we obtained. Nonetheless, we observed sequence-specific binding for nine non-consensus homeodomains, including Rhox6 and two novel homeodomains we have termed Dobox4 and Dobox5, indicating a potential means for acquiring additional diversity in DNA-binding specificity and function.

Comparison of PBM Data to Previously-Determined Homeodomain Binding Preferences

As a first step in the analysis of our data, we compared our data to previously-known binding sequences from the literature. Taking the 168 mouse proteins together with their closest ortholog in other metazoan species (regardless of the degree of similarity), the TRANSFAC and JASPAR databases contain at least one binding sequence corresponding to 97 mouse proteins or their orthologs (see Supplementary material for details). None of these proteins has more than 86 known binding sites, either in vitro or in vivo, in these databases. Nine of them (or an ortholog) have a PWM in the JASPAR database (derived from between 10 and 59 sequences obtained in vivo, in vitro, or both), and 58 more (or an ortholog) have a PWM in TRANSFAC (derived from between 5 and 86 binding sequences). An additional 30 of the 168 proteins we analyzed have between 1 and 4 known sites listed with a direct interaction observed in vivo or in vitro. We note that there are frequently multiple mouse homologs for each homeodomain in other species (e.g. Antp is the closest Drosophila homolog to the mouse Hox6, Hox7, Hox8, and Hox9 paralogs, so the Antp PWM represents the only data available for nine of the mouse homeodomains we analyzed).

Although the accuracy of the standard PWM model has been called into question, PWMs represent a straightforward means to compare binding activities on a coarse level. A visual comparison of the PWMs we derived from our data and those in the databases reveals reassuring similarities, but also discrepancies with the existing literature (Supplementary Table 1). For example, our PWMs for Lhx3, Meis1, Otx1/2, Nkx2-2, Pitx2, and Tgif1 are very similar to those previously determined. In some cases, however, our PWMs are somewhat different; for example, our Hmx3 PWM (resembling CAATTAA) is different from that previously determined from nine in vitro selected DNA sequences (resembling CAAGTGCGTG), although ours is very similar to those we obtained for the related proteins Hmx1 and Hmx2.

Perhaps the most obvious source of disagreement would be inconsistency in the initial data used to construct the motifs. We compared whether the individual sequences from JASPAR, which are determined by curators to be high-quality, all contain 8-mers with high scores in our data. In some cases, all of the source sequences in JASPAR contain at least one 8-mer with an E-score ≥ 0.45 in our data for the same protein; for example, all 41 of the human and mouse Lhx3 binding sequences meet this criterion, as do 17/18 Pbx1-binding sequences and 32/38 Nobox (Og2x) binding sequences. All of these proteins also have a PWM that is very similar to the one we derived from our data. In contrast, only one of ten in vitro selected sequences for the mouse En1 protein contains an 8-mer with E > 0.45 in our data, and the derived PWMs bear little resemblance (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, the measured binding affinity of En1 for this one sequence was considerably higher than for any of the other nine selected sequences (Catron et al., 1993).

We conclude that our data are in many cases consistent with previous data, although in many cases there are discrepancies. We note that the previous data are also not always in agreement with each other; for example the En1 PWMs in TRANSFAC and JASPAR are quite different from each other, and also from the Drosophila Engrailed PWM in TRANSFAC, illustrating that motifs in databases and the literature cannot all be taken as a gold standard. We propose that heterogeneity in methods used to produce the DNA-binding data in the literature may underlie many of the differences between our results and previous findings: not only were the binding sites for separate proteins identified by different means, but even individual TRANSFAC matrices for single proteins are frequently derived from binding sequences compiled from multiple experimental methods. Further, these sequences often exhibit ascertainment bias reflecting which particular sequences were chosen to be examined by the investigators. In contrast, our data are homogeneous and were generated on a uniform, unbiased platform under standardized conditions, such that the binding activities of the different proteins should be directly comparable.

For 71 of the proteins we analyzed, there is no in vitro or in vivo binding site data, and for the majority there is no PWM, in either mouse or the closest homolog in any species. To our knowledge, for several families, we describe a relatively uniform and apparently distinct binding profile for the first time. These encompass the Irx family (preferring sequences resembling TACATGTA), the Obox family (GGGGATTA), the Six family (G(G/A)TATCA), Gbx1/2 (CTAATTAG), and Pknox1/2 (CCTGTCA). Our data also include individual proteins with apparently unique sequence preferences, including Dux1 (CAATCAA), Hdx ((C/A)AATCA), Hmbox (TAACTAG), Homez (ATCGTTT), and Rhox11 (GCTGT(T/A)(T/A)). The variety in motifs we obtained motivated us to further explore the similarities and differences among homeodomains within our data set.

Homeodomains have Rich and Diverse Sequence Preferences

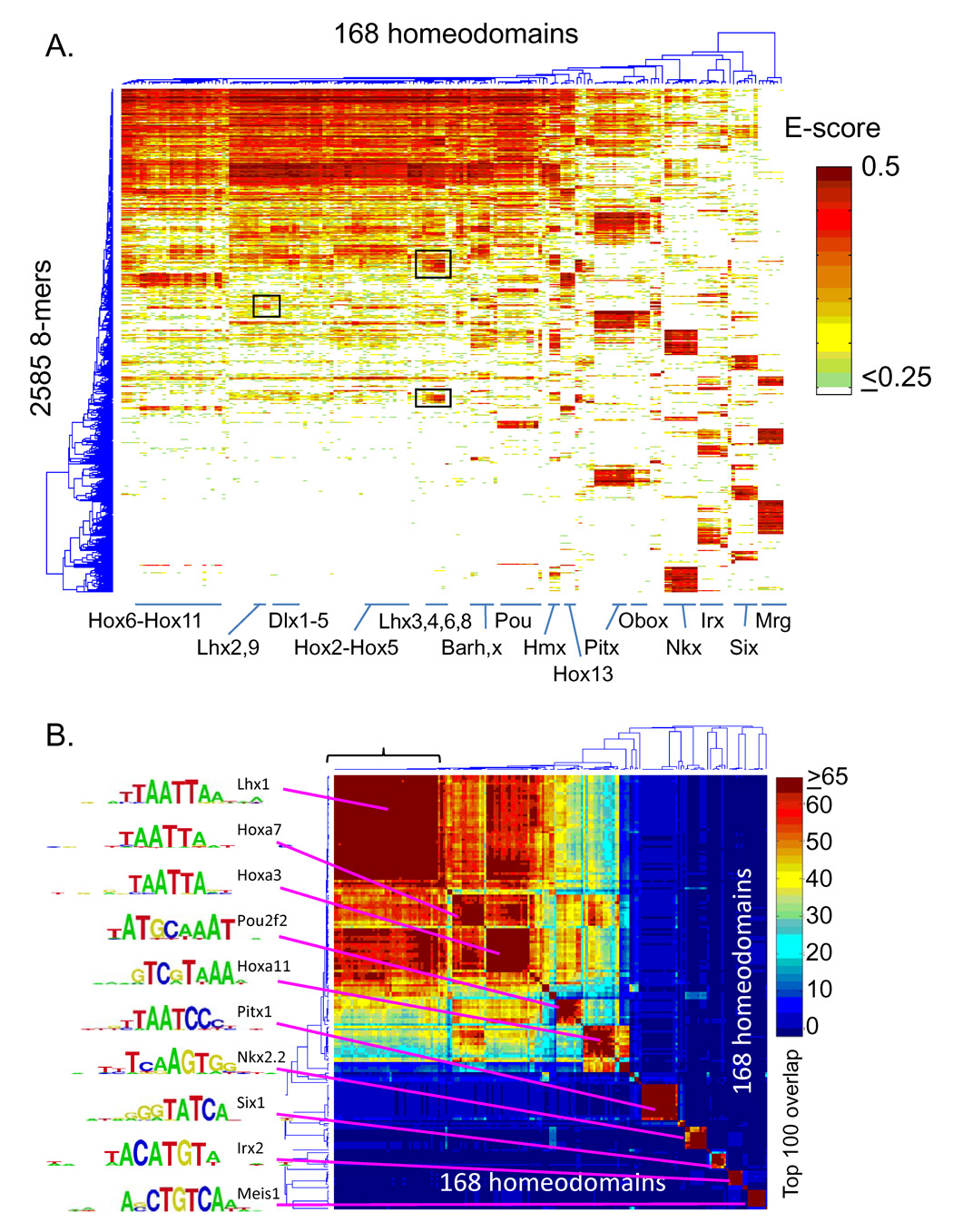

Figure 2A shows a 2-D clustering analysis of the E-scores of all 2,585 8-mers that were bound by at least one homeodomain with E > 0.45. On a coarse level, the major features of the data structure correspond to the major homeodomain subclasses, and these large clusters contain sequences similar to those previously established for these subclasses, when known (Banerjee-Basu et al., 2003). For example, the largest feature (encompassing the upper left part of Fig. 2A) includes the Hox subclasses and other homeodomains that prefer a canonical TAAT core (Svingen and Tonissen, 2006). Roughly half the homeodomains, however, have a stronger preference for other sequences, and many of the homeodomains that do bind canonical sequences also bind additional sequences (e.g., some of the Lhx classes are associated with the large TAAT-binding cluster, but also have their own clusters of preferred 8-mers, boxed in Fig. 2A). There are also instances of single proteins or small groups that have a distinctive 8-mer profile (Fig. 2A). Indeed, when considering the top 100 highest-affinity 8-mers for each homeodomain, we identified 33 clearly separate DNA binding activities. These binding profiles are distinguishable on the basis of limited overlap among the top 100 8-mers (among all 32,896 possible 8-mers when reverse complements are merged) for pairs of homeodomains (Fig. 2B). As controls, our dataset includes 21 instances in which the same homeodomain was analyzed twice, either (i) as a freshly-expressed aliquot from the same construct (3 proteins) or an alternate construct (7 proteins), or (ii) as a different gene with the same homeodomain sequence but different flanking residues (11 proteins). These 21 replicates invariably correlate highly: among them, the top 100 overlap was 85 ± 8, such that proteins sharing fewer than 66 of 100 top 8-mers (99% confidence interval) were considered to have distinct binding activities. Figure 2B shows the resulting 33 specificity groups along the diagonal, accompanied by PWMs for representative members of each of the large families.

Figure 2. Overview of homeodomains 8-mer binding profiles reveals distinct sequence preferences.

(A) Hierarchical agglomerative clustering analysis of E-score data for 2,585 8-mers with E > 0.45 in at least one experiment. Boxed regions are referred to in the text. The position of exemplary homeodomain families within the dendrogram are indicated in order to highlight the diversity of overall 8-mer profiles. (B) Clustering analysis of the matrix of overlaps in the top 100 8-mers (of all 32,896) for each pair of homeodomains. The bracket indicates the experiments analyzed in Figure 3. Logos for representative members of the major groups were determined using the Seed-and-Wobble method (Berger et al., 2006).

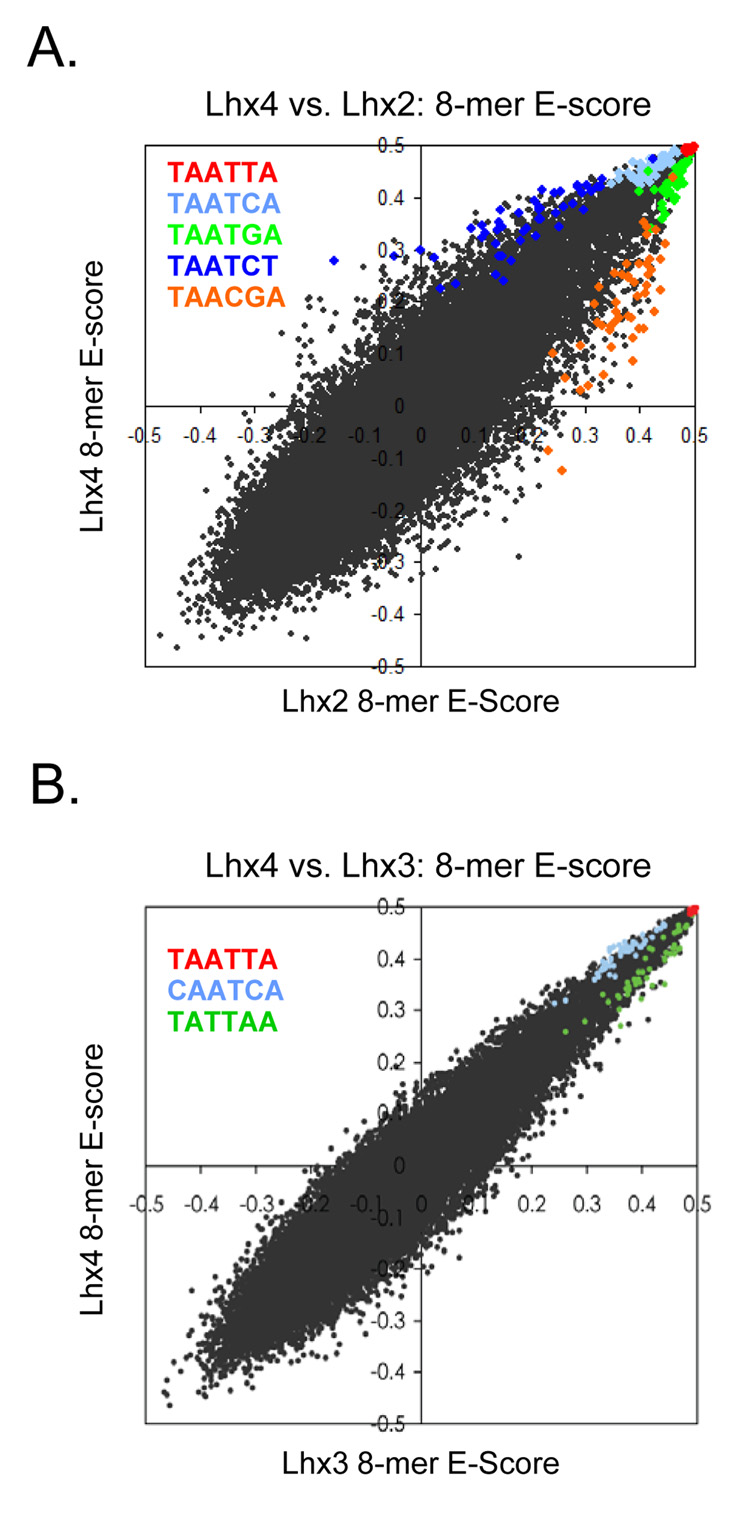

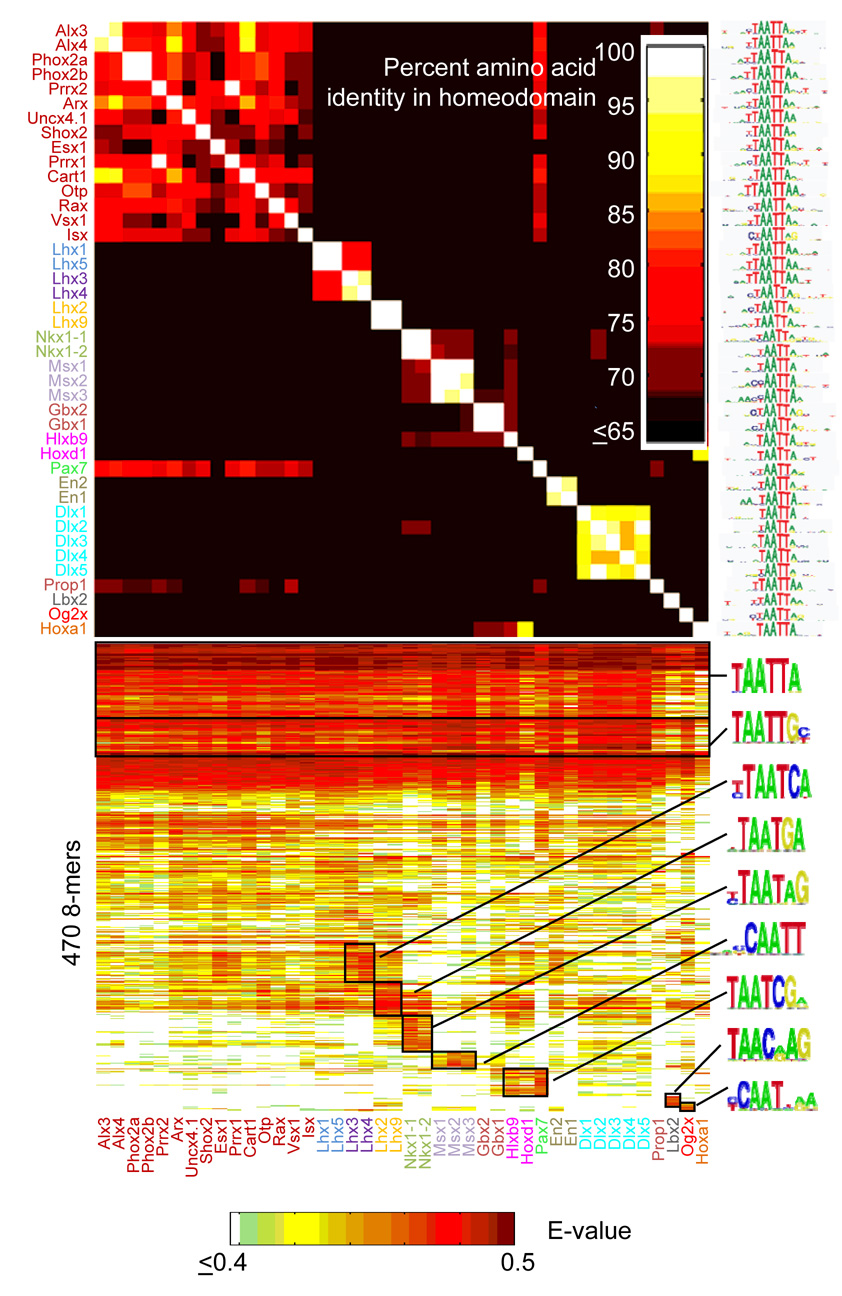

Members within each of these 33 groups, however, can be further distinguished by their lower-affinity binding sites and/or by differences in relative preference among the top 100 8-mers. For example, among the large group in the upper left of Figure 2B (bracketed) comprised of 42 proteins that are indistinguishable by the top 100 criterion, we identified 15 distinct subgroups on the basis of differences in their E-score profiles over all 8-mers (Fig. 3). Even though all proteins in this large group exhibit essentially the same dominant motif, clear sequence patterns are associated with the 8-mers distinctively preferred by each subgroup, and these patterns correlate with differences in their amino acid sequences (Fig. 3). This is further illustrated in Figure 4. Lhx2 and Lhx4 both bind the same highest affinity sites (8-mers containing TAATTA) but show clear, consistent preferences for different moderate (TAATGA vs. TAATCA) and lower (TAACGA vs. TAATCT) affinity sites (Fig. 4A). Lhx3 and Lhx4 show greater similarity, both in binding profile and amino acid sequence, yet they have subtly different preferences for weaker 8-mers (Fig. 4B). These differences only become apparent due to the richness of our dataset in capturing precise binding specificities at word-by-word resolution.

Figure 3. Homeodomains with virtually identical dominant motifs and top 100 8-mer preferences have differing preferences for many 8-mers.

Bottom, heat-map as in Figure 2, but restricted to the 470 8-mers with E > 0.45 in at least one of the experiments shown. Color of labels indicates groups that are distinct by our criteria. Logos were derived using ClustalW with the 8-mers in the boxed regions as inputs. Top, amino-acid similarities among these 42 homeodomains, as in Figure 1.

Figure 4. Scatter plots showing differences in E-scores for individual 8-mers between Lhx family members.

(A) Comparison of Lhx2 and Lhx4. (B) Comparison of Lhx3 and Lhx4. 8-mers containing each 6-mer sequence (inset) are highlighted, revealing clear systematic differences between sequence preferences despite essentially identical dominant motifs and sets of top 100 8-mers for these homeodomains.

We repeated the analysis of Figure 3 for all 18 of the major groups shown along the diagonal in Figure 2B to examine whether they could be further divided by fine-grained differences in specificity (Supplementary Figure 7). We considered: (1) whether the motif(s) derived for the two proteins were clearly distinct, and (2) whether differences in the E-score profiles between proteins also contain motifs that distinguish the two binding activities. Our analysis identified a total of 65 distinct binding patterns that have a striking correlation with amino acid sequence similarity among the homeodomains (Supplementary Figure 7 and see below). Although an approximation, this likely represents a lower bound on the true number of distinct patterns; for instance, our analysis places Lhx3 and Lhx4 in the same subgroup, yet we can still discern subtle differences in their 8-mer binding profiles (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

From this analysis we conclude that homeodomains encode distinctive DNA-binding activities and that there are often major differences between the activities of individual proteins with similar dominant sequence preferences. We also find that the dominant motif is usually unable to explain all of the data, and is inferior to the full 8-mer profile in predicting the outcome of a similar experiment on an independent array (Supplementary Figure 3 and (Chen et al., 2007)). Rather, our results are consistent with a model in which homeodomain sequence preferences may be best described as a composite of binding activities, possibly representing different binding modes with different relative affinities. This idea is supported by the report that Nkx2-5 has two distinct binding activities, one with higher affinity than the other (Chen and Schwartz, 1995); indeed, the Nkx2 group, like Lhx3 and Lhx4, is one of the 65 groups that appears as if it may be further subdivided (Supplementary Figure 7).

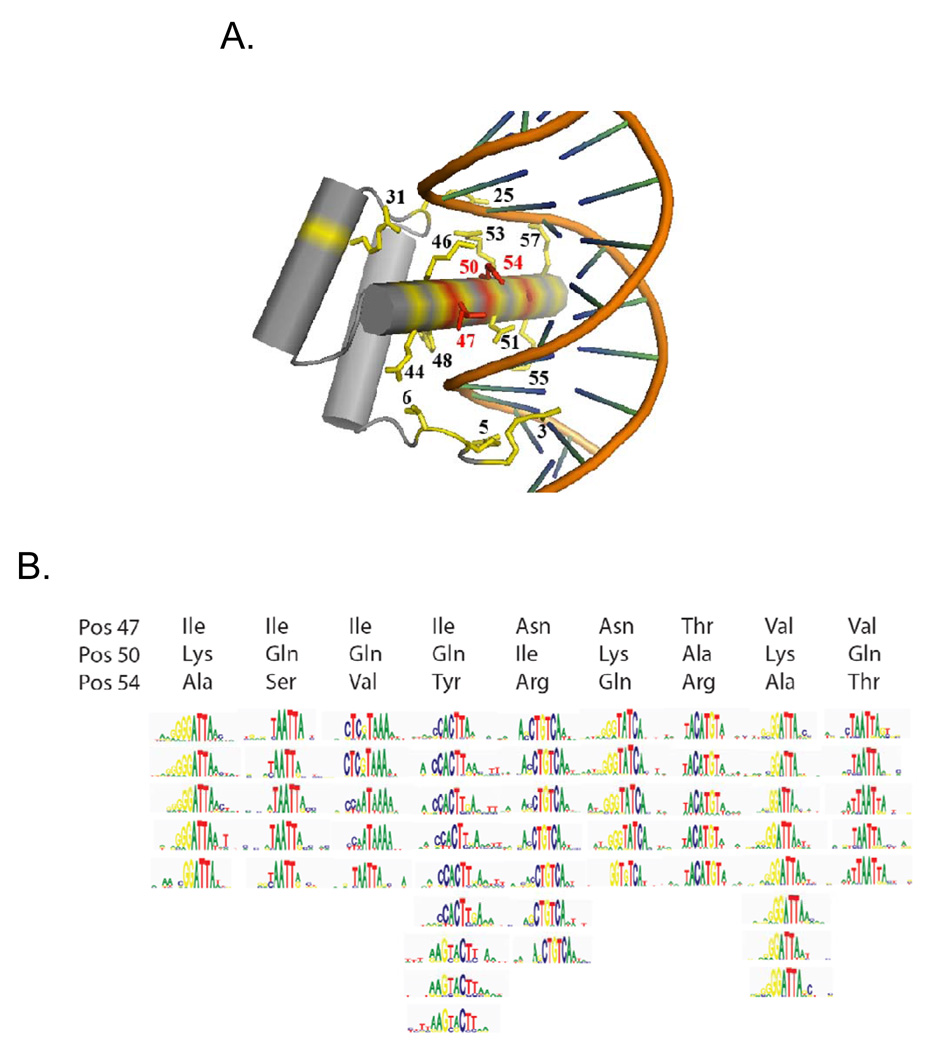

Moreover, even the dominant motifs we obtain do not correspond perfectly with the identities of the canonical homeodomain specificity residues. The homeodomain binds DNA predominantly through interactions between helix 3 (recognition helix) and the major groove, and base-specific contacts made by positions 47, 50, and 54 are believed to be the main determinants of differences in binding specificity (Laughon, 1991) (Fig. 5A, shown in red). Indeed, we were able to form groups harboring similar dominant motifs simply by partitioning homeodomains according to their amino acid identity at these three positions (Fig. 5B). Our results are consistent with previous reports; for instance, replacing glutamine with lysine at position 50 has been shown to dramatically alter the binding specificity through several newly-formed hydrogen bonds to guanines (Tucker-Kellogg et al., 1997). These three residues alone are not sufficient to fully capture the entire binding activity, however, and in some cases even the dominant motifs differ among proteins that have the same identity at these three residues (Fig. 5B). Residues in the N-terminal arm have also been shown to influence binding specificities of homeodomains through minor groove interactions (Ekker et al., 1994); however, the identities at these residues (3, 6, and 7) do not correspond to the variation in Fig. 5B (data not shown). Additional recognition positions must also be necessary to explain the differences in binding specificity we have observed for related homeodomains: while we cannot exclude a molecular code controlling homeodomain DNA-binding activity (Damante et al., 1996), such a code is likely to be complex if one considers the full range of binding sequences.

Figure 5. Correspondence between canonical homeodomain amino acid sequence specificity residues and dominant motifs.

(A) Protein-DNA interface for the Drosophila Engrailed protein (Kissinger et al., 1990). The three primary specificity residues discussed in the text are shown in red. The remaining residues considered in our nearest-neighbor analysis are in yellow. (B) Motifs for all homeodomains in our dataset containing each of the displayed combinations of residues. For clarity, only those combinations occurring between 5 and 10 times are shown. Logos represent PWMs determined using the Seed-and-Wobble method (Berger et al., 2006).

Correlation Between Homeodomain Amino Acid Sequence Similarity and 8-mer Binding Profile Similarity Facilitates Prediction of Binding Sequences Across the Animal Kingdom

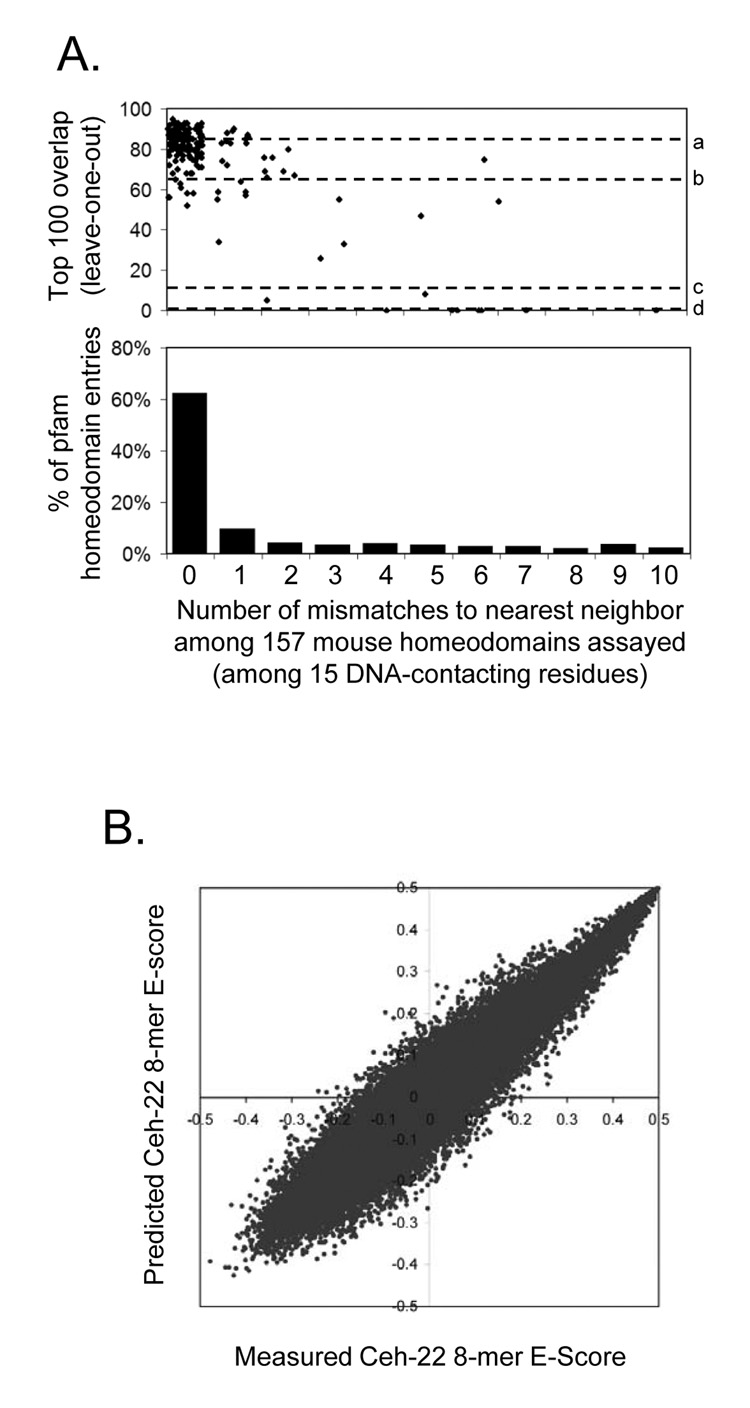

To more systematically and thoroughly approach the problem of identifying determinants of homeodomain sequence preferences, we tested the efficacy of a variety of methods to predict the full 8-mer binding profiles using only the amino acid sequences as inputs (see Supplementary document for details). We evaluated each approach using leave-one-out cross validation (in which each homeodomain in turn was “held out” and its full 8-mer binding profile predicted) to test our success at reproducing the 8-mer data for each of the 157 non-identical homeodomains, using Spearman correlation, top 100 overlap, and Root Mean Squared Error as success criteria in predicting the 8-mer profile. The most effective overall approach was a nearest-neighbor method, in which the 8-mer data were transferred from the homeodomain with the fewest number of mismatches over a set of 15 DNA-contacting amino acids (averaging the E-scores in the case of ties). These 15 residues (3, 5, 6, 25, 31, 44, 46, 47, 48, 50, 51, 53, 54, 55, 57; Fig. 5A) account for all specific base-pair and phosphate backbone contacts in crystal structures for the Engrailed homeodomain (Fraenkel et al., 1998; Kissinger et al., 1990). The number of overlaps between the measured and predicted top 100 8-mers correlates with the distance to the closest example in the data, with zero, one, or two mismatches typically yielding predictions that are as close as an experimental replicate (Fig. 6A). This result is consistent with our previous assessment of homeodomain DNA-binding activity subclassifications, since there are more than 65 different naturally occurring variants among these 15 residues, groupings of which closely correspond to those obtained from the 8-mer profiles (see Supplementary material for details).

Figure 6. Correspondence between homeodomain DNA-contacting amino acid sequence residues and 8-mer DNA binding profiles.

(A) Top, scatter plot showing the top 100 overlap between real and predicted 8-mer binding profiles from leave-one-out cross-validation for our nearest-neighbor approach. Dashed lines indicate the following benchmarks: a) median, experimental replicates; b) 99% confidence, experimental replicates; d) median, randomized homeodomain labels; d) median, randomized 8-mer labels. Within each bin, the X-axis values have been nudged randomly for visualization. Bottom, the proportion of 3,693 pfam entries with the indicated identity to at least one mouse homeodomain analyzed. (B) Predicted vs. measured 8-mer E-scores for C. elegans Ceh-22.

Consistent with the fact that much of the amino acid sequence variation among animal homeodomains is found in the mouse (Fig. 1), the number of mismatches among these 15 amino acids from most mouse homeodomains to their homologs in species as distant as Drosophila is zero (Fig. 1, Fig. 6A, and Supplementary online data). We therefore applied the nearest-neighbor approach to project high-confidence 8-mer binding profiles for homeodomain proteins in 24 species (Supplementary online data). We found that in many cases the predicted data were consistent with known motifs and binding sequences, even when the remainder of the homeodomain sequence had diverged considerably. We experimentally determined 8-mer E-scores for the C. elegans homeodomain protein Ceh-22 by PBM and observed striking correlation with its predicted profile (Pearson correlation = 0.93, 78 of the top 100 overlap; Fig. 6B) despite an overall difference of 11 amino acids within the homeodomain to the most similar mouse protein. Our inferred 8-mer profiles closely mirror quantitative in vitro measurements for the Drosophila Engrailed homeodomain as well (Supplementary Figure 8) (Damante et al., 1996).

Sequences Preferred by Homeodomains in vitro Correspond to Sites Preferentially Bound in vivo

Finally, we asked whether the homeodomain monomer binding preferences we identified in vitro reflect sequences preferred in vivo. Anecdotally, our highest predicted binding sequences do correspond to known in vivo binding sites. For example, in the predicted 8-mer profile for sea urchin Otx, a previously identified in vivo binding sequence (TAATCC, from the Spec2a RSR enhancer) (Mao et al., 1994) is contained in our top predicted 8-mer sequence, and, more strikingly, it is embedded in our 5th highest predicted 8-mer sequence (TTAATCCT). At greater evolutionary distance, three of the four Drosophila Tinman binding sites in the minimal Hand cardiac and hematopoietic (HCH) enhancer (Han and Olson, 2005) are contained within the 2nd (TCAAGTGG), 5th (ACCACTTA), and 9th (GCACTTAA) ranked 8-mers (the fourth overlaps the 428th ranked 8-mer (CAATTGAG), but also overlaps with a GATA binding site (Han and Olson, 2005) and may have constraints on its sequence in addition to binding Tinman).

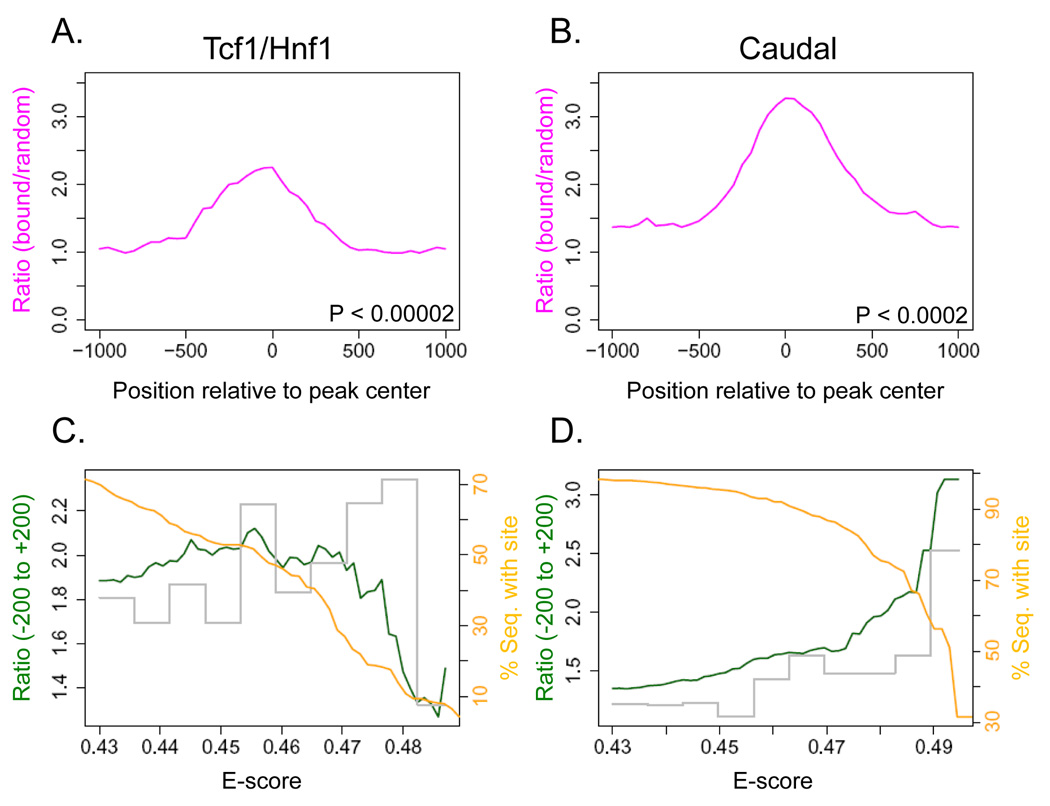

To ask more generally whether occupied sites in vivo contain sequences preferred in vitro, we examined six ChIP-chip or ChIP-seq data sets in the literature that involved immunoprecipitation of homeodomain proteins that we analyzed, or homologs of proteins we analyzed that shared at least 14 of the 15 DNA-contacting amino acids. In all cases we observed enrichment for monomer binding sites in the neighborhood of the bound fragments, with a peak at the center (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure 9). Figures 7A and B show two examples, Drosophila Caudal (Li et al., 2008) and human Tcf1/Hnf1 (Odom et al., 2006). For Caudal, the size of this ratio peak increased dramatically with E-score cutoff, indicating that the most preferred in vitro monomer binding sequences correspond to the most enriched in vivo binding sites (cutoff E > 0.49) (Figure 7D) (51% of bound fragments have such an 8-mer vs. 17% in randomly-selected fragments). For Tcf1/Hnf1, however, the majority of sequences bound in vivo do not contain the best in vitro binding sequences (E > 0.49), although most do contain at least one 8-mer with E > 0.45 (Figure 7C) (53%, vs. 27% in random fragments), suggesting utilization of weaker binding sites. Similar results were obtained with PWMs (data not shown). Thus, the requirement for highest-affinity binding sequences may vary among homeodomain proteins, species, or under different physiological contexts. Nonetheless, a large proportion of the in vivo binding events apparently involve the monomeric homeodomain sequence preferences which can be derived in vitro.

Figure 7. Enrichment of sequences preferred in vitro within genomic sequences bound in vivo by the same protein.

(A) Comparison of bound to randomly-selected sequences for human Tcf1/Hnf1 (Odom et al., 2006), showing the relative enrichment of our 8-mers (at 0.456 cutoff). P-value was calculated for the interval (−200 to +200) by the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney rank sum test, comparing the number of occurrences per sequence in the bound set vs. the background set. (B) Same as (A), but for Drosophila Caudal (Li et al., 2008) (at 0.493 cutoff). (C) Relative enrichment (green line) in the −200 to + 200 window for varying cutoffs of the E-score for Tcf1/Hnf1. The orange line shows the proportion of bound fragments with at least one such sequence in the same interval. The grey bars show the relative enrichment of 8-mers within each interval of 0.1, e.g. only 0.43–0.436 for the first interval. (D) Same as (C), but for Caudal.

Discussion

Our data provide a new level of resolution in the analysis of homeodomain sequence specificity. Our analyses show that homeodomains have distinctive sequence preferences, which may contribute to the strong selective pressure on their amino acid sequences as well as to the biological specificity in target genes and diversity in function among the homeodomain proteins. Our findings should provide a fertile basis for future study of homeodomain function and evolution, and may influence our understanding of evolved diversity in other transcription factor families.

One of the long-standing goals in the study of DNA-protein interactions has been to elucidate the relationships between amino-acid residues and base preferences. Although it is clear that key residues can exert a strong influence, with others held constant (Hanes and Brent, 1989; Treisman et al., 1989), there is also evidence that alterations in the overall structure of DNA-binding domains can influence the DNA sequence preferences in unexpected ways (Miller and Pabo, 2001; Wolfe et al., 2001). Interactions among residues in the PWM (Benos et al., 2002) further complicate derivation of a deterministic recognition code. Full 8-mer profiles provide a new way to approach this problem. While there is a correspondence between the canonical homeodomain DNA-binding specificity residues and the dominant motif, the correspondence is imperfect, and the dominant motif does not fully describe the complete binding profile, consistent with a model in which homeodomains have multiple binding modes. Perhaps as a consequence, our analyses suggest that categorization of the 8-mer profile on the basis of the full suite of DNA-contacting residues may be a more appropriate and practical paradigm for homeodomain sequence recognition than a molecular encoding of a PWM.

This idea is supported by our accurate prediction of full binding profiles over vast evolutionary differences. In fact, it is striking how little the entire homeodomain family has diverged at these residues since the common ancestor of all animals, considering that the potential for diversity in homeodomain DNA-binding activity seems well-suited for duplication and divergence. While newer binding activities (e.g., those of Dobox4, Dobox5, Rhox6, and Rhox11) have apparently arisen since the divergence of mice and humans (there is no apparent homolog of these homeodomains in any species more distant than rat), the range of possible configurations even at the three canonical specificity residues (47, 50, 54) appears to be sparsely populated in nature.

In all cases we tested, including predicted profiles for Drosophila homeodomains, the preferred monomer binding 8-mer sequences we obtained in vitro are enriched at the center of genomic fragments bound by the same protein in vivo. From this we conclude that monomer binding preferences are likely to be a component of targeting mechanisms in general. Other factors (e.g. the chromatin landscape and protein-protein interactions) must also play a role in targeting, as only a small fraction of all possible binding sites are occupied. We cannot exclude the possibility that the homeodomains we analyzed can undergo a radical change in binding specificity when they form complexes, and that they rely on this or other mechanisms for a subset of in vivo binding events. Nonetheless, our demonstration that there are strong relationships between in vitro sequence preferences and in vivo binding sites supports the biological relevance of binding preferences of homeodomain monomers, and indicates that our data should be of widespread use for identifying regulatory sites in vivo.

Experimental Procedures

Cloning, expression, and purifying homeodomains

Homeodomain open reading frames, consisting of the pfam-defined homeodomain and 15 amino acids of flanking sequence (or to the end of the full open reading frame) were cloned into pMAGIC1 (Li and Elledge, 2005) by either RT-PCR from pooled mouse mRNA or by gene synthesis (DNA 2.0). All clones were sequence verified (Supplementary file “Protein and DNA sequence”). We transferred the inserts into a T7-GST-tagged variant of pML280 following (Li and Elledge, 2005). We expressed proteins by either (i) purification from E. coli C41 DE3 cells (Lucigen), or (ii) in vitro translation reactions (Ambion ActivePro Kit) without purification. Essentially identical results were obtained by either method (Supplementary Figure 1).

Microarray design and use

The construction of ‘all 10-mer’ universal PBMs using a de Bruijn sequence of order 10 has already been described (Berger et al., 2006) and is described in more detail in conference proceedings posted at http://thebrain.bwh.harvard.edu/RECOMB2007.pdf. For this study, we further optimized our design to achieve greater coverage of gapped k-mers (see Supplementary material for details). PBM assays were performed essentially as described previously (Berger et al., 2006), except that four proteins were simultaneously assayed in separate sectors of a single microarray, and scanned using at least three different laser power settings to best capture a broad range of signal intensities and ensure signal intensities below saturation for all spots. Images were analyzed using GenePix Pro version 6.0 software (Molecular Devices), bad spots were manually flagged and removed, and data from multiple Alexa488 scans of the same slide were combined using ‘masliner’ software (Dudley et al., 2002) and normalized as described previously (Berger et al., 2006).

Sequence Analysis and Motif Construction

We provide several scores for each 8-mer in each experiment: (1) Median Intensity, (2) Z-Score, (3) Enrichment Score (E-Score), and (4) False Discovery Rate Q-Value for the E-Score. The Median Intensity and Z-score measures follow standard statistical procedures. The E-score has already been described in detail (Berger et al., 2006). Briefly, for each 8-mer (contiguous or gapped) we consider the collection of all probes harboring a match as the “foreground” feature set and the remaining probes as a “background” feature set. We compare the ranks of the top half of the foreground with the ranks of the top half of the background by computing a modified form of the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney (WMW) statistic scaled to be invariant of foreground and background sample sizes. The E-Score ranges from +0.5 (most favored) to −0.5 (most disfavored). We compute a False Discovery Rate Q-Value for the E-Score by comparing it to the null distribution of E-Scores (over 32,896 8-mers) calculated by randomly shuffling the mapping among the 41,944 probe sequences and intensities (repeated 20 times) (Subramanian et al., 2005). In computing all of the above scores, we do not consider probes for which the 8-mer occupies the most distal position on the probe (5’ with respect to the template strand) or for which the 8-mer overlaps the 24-nt primer region. We derive PWMs using the “Seed-and-Wobble” algorithm (Berger et al., 2006).

Predicting 8-mer Profiles and Scoring the Predictions

We considered two general methods for predicting 8-mer binding profiles on the basis of the primary amino acid sequence: nearest-neighbor and regression. In the nearest neighbor (NN) approach, we predicted the 8-mer profile of any given homeodomain protein by taking the 8-mer profile(s) of its nearest neighbor(s) (averaging in the case of a tie). For regression, we converted the homeodomain amino-acid sequence alignment to a binary representation by replacing all 20 standard amino acids in any of the canonical residue positions with unique 20-bit binary flags, the dimensionality was reduced by Principal Components Analysis (PCA), and a distinct model was learned for each 8-mer and for each homeodomain (i.e., a separate model for all 157 × 32,896 entries in the data table). We considered several variations of the distance metric used (e.g. number of mismatches vs. AA similarity scores) and/or the residues considered (all 57 residues, 15 DNA-contacting residues, or five known specificity residues).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses

We obtained 1,331 bound sequences in the Caudal data set by selecting those in the 1% FDR set where a peak was also reported (Li et al., 2008). We obtained 427 bound sequences in the Tcf1/Hnf1 data set (Odom et al., 2006) by implementing a program to perform the procedure described at http://jura.wi.mit.edu/young_public/hESregulation/Regions.html to the raw data. To create Figure 7 A and B, we added 1 kb to either side of the ChIP-chip peak (for Caudal) or the center of the identified bound sequence (for Tcf1/Hnf1), and determined the relative enrichment in overlapping 500-base windows, using a 10-fold excess of 2 kb random genomic regions taken from the Drosophila genome (for Caudal) or the human genome (for Tcf1/Hnf1) as a background set.

Data availability

Supplementary data and all original data files are online at http://hugheslab.ccbr.utoronto.ca/supplementary-data/homeodomains1/ and http://the_brain.bwh.harvard.edu/pbms/webworks2/. Array probe sequences are found at http://the_brain.bwh.harvard.edu/ and microarray data has been deposited at GEO with Platform ID GPL6760 and Series ID GSE11239.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute, the Ontario Research Fund, and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research to T.R.H., M.L.B. and G.B.B.; by the National Science Foundation to M.F.B.; and by grant R01 HG003985 from NIH/NHGRI to M.L.B. We thank Genita Metzler, Hanna Kuznetsov, Chi-Fong Wang, Anastasia Vedenko, Frédéric Bréard, David Coburn, Dimitri Terterov, Ally Yang, Harm van Bakel, Wing Chang, and John Calarco for technical assistance, and Shoshana Wodak, Fritz Roth, Charlie Boone, Jack Greenblatt, Ben Blencowe, Bill Stanford, and Trevor Siggers for helpful discussions and critical evaluation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Banerjee-Basu S, Moreland T, Hsu BJ, Trout KL, Baxevanis AD. The Homeodomain Resource: 2003 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:304–306. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benos PV, Bulyk ML, Stormo GD. Additivity in protein-DNA interactions: how good an approximation is it? Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4442–4451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger MF, Philippakis AA, Qureshi AM, He FS, Estep PW, 3rd, Bulyk ML. Compact, universal DNA microarrays to comprehensively determine transcription-factor binding site specificities. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1429–1435. doi: 10.1038/nbt1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell TK, Huang J, Ma A, Kretzner L, Alt FW, Eisenman RN, Weintraub H. Binding of myc proteins to canonical and noncanonical DNA sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5216–5224. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryne JC, Valen E, Tang MH, Marstrand T, Winther O, da Piedade I, Krogh A, Lenhard B, Sandelin A. JASPAR, the open access database of transcription factor-binding profiles: new content and tools in the 2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D102–D106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult CJ, Blake JA, Richardson JE, Kadin JA, Eppig JT, Baldarelli RM, Barsanti K, Baya M, Beal JS, Boddy WJ, et al. The Mouse Genome Database (MGD): integrating biology with the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D476–D481. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A, Biggin MD. A comparison of in vivo and in vitro DNA-binding specificities suggests a new model for homeoprotein DNA binding in Drosophila embryos. Embo J. 1999;18:1598–1608. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brodsky AS, Li W, Meyer CA, Szary AJ, Eeckhoute J, Shao W, Hestermann EV, Geistlinger TR, et al. Chromosome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor binding reveals long-range regulation requiring the forkhead protein FoxA1. Cell. 2005;122:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catron KM, Iler N, Abate C. Nucleotides flanking a conserved TAAT core dictate the DNA binding specificity of three murine homeodomain proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2354–2365. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SK, Mann RS. The segment identity functions of Ultrabithorax are contained within its homeo domain and carboxy-terminal sequences. Genes Dev. 1993;7:796–811. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Schwartz RJ. Identification of novel DNA binding targets and regulatory domains of a murine tinman homeodomain factor, nkx-2.5. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15628–15633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Hughes TR, Morris Q. RankMotif++: a motif-search algorithm that accounts for relative ranks of K-mers in binding transcription factors. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:i72–i79. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damante G, Pellizzari L, Esposito G, Fogolari F, Viglino P, Fabbro D, Tell G, Formisano S, Di Lauro R. A molecular code dictates sequence-specific DNA recognition by homeodomains. Embo J. 1996;15:4992–5000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson LA, Joh T, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. A tissue-specific MAR/SAR DNA-binding protein with unusual binding site recognition. Cell. 1992;70:631–645. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90432-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley AM, Aach J, Steffen MA, Church GM. Measuring absolute expression with microarrays with a calibrated reference sample and an extended signal intensity range. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7554–7559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112683499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekker SC, Jackson DG, von Kessler DP, Sun BI, Young KE, Beachy PA. The degree of variation in DNA sequence recognition among four Drosophila homeotic proteins. Embo J. 1994;13:3551–3560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekker SC, von Kessler DP, Beachy PA. Differential DNA sequence recognition is a determinant of specificity in homeotic gene action. Embo J. 1992;11:4059–4072. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel E, Rould MA, Chambers KA, Pabo CO. Engrailed homeodomain-DNA complex at 2.2 A resolution: a detailed view of the interface and comparison with other engrailed structures. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:351–361. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukubo-Tokunaga K, Flister S, Gehring WJ. Functional specificity of the Antennapedia homeodomain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6360–6364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galant R, Walsh CM, Carroll SB. Hox repression of a target gene: extradenticle-independent, additive action through multiple monomer binding sites. Development. 2002;129:3115–3126. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Olson EN. Hand is a direct target of Tinman and GATA factors during Drosophila cardiogenesis and hematopoiesis. Development. 2005;132:3525–3536. doi: 10.1242/dev.01899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanes SD, Brent R. DNA specificity of the bicoid activator protein is determined by homeodomain recognition helix residue 9. Cell. 1989;57:1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbison CT, Gordon DB, Lee TI, Rinaldi NJ, Macisaac KD, Danford TW, Hannett NM, Tagne JB, Reynolds DB, Yoo J, et al. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2004;431:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Watt AJ, Gautier P, Gilchrist D, Driehaus J, Graham GJ, Keebler J, Prugnolle F, Awadalla P, Forrester LM. A murine specific expansion of the Rhox cluster involved in embryonic stem cell biology is under natural selection. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:212. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R, Passner JM, Rohs R, Jain R, Sosinsky A, Crickmore MA, Jacob V, Aggarwal AK, Honig B, Mann RS. Functional specificity of a Hox protein mediated by the recognition of minor groove structure. Cell. 2007;131:530–543. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger CR, Liu BS, Martin-Blanco E, Kornberg TB, Pabo CO. Crystal structure of an engrailed homeodomain-DNA complex at 2.8 A resolution: a framework for understanding homeodomain-DNA interactions. Cell. 1990;63:579–590. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90453-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larroux C, Fahey B, Degnan SM, Adamski M, Rokhsar DS, Degnan BM. The NK homeobox gene cluster predates the origin of Hox genes. Curr Biol. 2007;17:706–710. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughon A. DNA binding specificity of homeodomains. Biochemistry. 1991;30:11357–11367. doi: 10.1021/bi00112a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MZ, Elledge SJ. MAGIC, an in vivo genetic method for the rapid construction of recombinant DNA molecules. Nat Genet. 2005;37:311–319. doi: 10.1038/ng1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XY, Macarthur S, Bourgon R, Nix D, Pollard DA, Iyer VN, Hechmer A, Simirenko L, Stapleton M, Hendriks CL, et al. Transcription Factors Bind Thousands of Active and Inactive Regions in the Drosophila Blastoderm. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon A, Ridner G, Walker MD. Role of intrinsic DNA binding specificity in defining target genes of the mammalian transcription factor PDX1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:54–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, McGinnis W. Mapping functional specificity in the Dfd and Ubx homeo domains. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1071–1081. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RS, Chan SK. Extra specificity from extradenticle: the partnership between HOX and PBX/EXD homeodomain proteins. Trends Genet. 1996;12:258–262. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao CA, Gan L, Klein WH. Multiple Otx binding sites required for expression of the Strongylocentrotus purpuratus Spec2a gene. Dev Biol. 1994;165:229–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matys V, Fricke E, Geffers R, Gossling E, Haubrock M, Hehl R, Hornischer K, Karas D, Kel AE, Kel-Margoulis OV, et al. TRANSFAC: transcriptional regulation, from patterns to profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:374–378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Pabo CO. Rearrangement of side-chains in a Zif268 mutant highlights the complexities of zinc finger-DNA recognition. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:309–315. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Berger MF, Jona G, Wang XS, Muzzey D, Snyder M, Young RA, Bulyk ML. Rapid analysis of the DNA-binding specificities of transcription factors with DNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1331–1339. doi: 10.1038/ng1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom DT, Dowell RD, Jacobsen ES, Nekludova L, Rolfe PA, Danford TW, Gifford DK, Fraenkel E, Bell GI, Young RA. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human hepatocytes. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100059. 2006 0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overdier DG, Porcella A, Costa RH. The DNA-binding specificity of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/forkhead domain is influenced by amino-acid residues adjacent to the recognition helix. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2755–2766. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkovic A, Yan C, Yan W, Klysik M, Matzuk MM. Obox, a family of homeobox genes preferentially expressed in germ cells. Genomics. 2002;79:711–717. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A, Alkema W, Engstrom P, Wasserman WW, Lenhard B. JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D91–D94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingen T, Tonissen KF. Hox transcription factors and their elusive mammalian gene targets. Heredity. 2006;97:88–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman J, Gonczy P, Vashishtha M, Harris E, Desplan C. A single amino acid can determine the DNA binding specificity of homeodomain proteins. Cell. 1989;59:553–562. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker-Kellogg L, Rould MA, Chambers KA, Ades SE, Sauer RT, Pabo CO. Engrailed (Gln50⤍Lys) homeodomain-DNA complex at 1.9 A resolution: structural basis for enhanced affinity and altered specificity. Structure. 1997;5:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS, Desplan C. Structural basis of Hox specificity. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:297–300. doi: 10.1038/7524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolberger C. Homeodomain interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:62–68. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe SA, Grant RA, Elrod-Erickson M, Pabo CO. Beyond the "recognition code": structures of two Cys2His2 zinc finger/TATA box complexes. Structure. 2001;9:717–723. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00632-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary data and all original data files are online at http://hugheslab.ccbr.utoronto.ca/supplementary-data/homeodomains1/ and http://the_brain.bwh.harvard.edu/pbms/webworks2/. Array probe sequences are found at http://the_brain.bwh.harvard.edu/ and microarray data has been deposited at GEO with Platform ID GPL6760 and Series ID GSE11239.