Abstract

Objective:

Women 25 to 45 years old are at risk for weight gain and future obesity. This trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy of two interventions relative to a control group in preventing weight gain among normal or overweight women and to identify demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial factors related to weight gain prevention.

Research Methods and Procedures:

Healthy women (N = 284), ages 25 to 44, with BMI < 30 were randomized to one of three intervention conditions: a clinic-based group, a correspondence course, or an information-only control. Intervention was provided over 2 years, with a follow-up at Year 3. BMI and factors related to eating and weight were assessed yearly.

Results:

Over the 3-year study period, 40% (n = 114) of the women remained at or below baseline body weight (±2 lbs), and 60% gained weight (>2 lbs). Intervention had no effect on weight over time. Independently of intervention, women who were older, not actively dieting to lose weight, and who reported less perceived hunger at baseline were more likely to be successful at weight maintenance. Weight maintenance also was associated with increasing dietary restraint (conscious thoughts and purposeful behaviors to control calorie intake) and decreasing dietary disinhibition (the tendency to lose control over eating) over time.

Discussion:

This study raises concern about the feasibility and efficacy of weight gain prevention interventions because most women were interested in weight loss, rather than weight gain prevention, and the interventions had no effect on weight stability. Novel approaches to the prevention of weight gain are needed.

Keywords: weight gain prevention, women, dietary restraint, dietary disinhibition

Introduction

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among American adults continues to rise. Although weight loss in a typical behavioral weight control intervention averages 0.5 kg/wk, most adults will ultimately regain weight lost during treatment (1-3). The difficulties of sustaining long-term weight loss, in conjunction with increasing rates of obesity, have led to recommendations for programs to prevent weight gain and future obesity (4,5). However, the results of initial efforts at primary obesity prevention, that is targeting individuals who are not currently overweight with the hope of changing lifestyle factors associated with weight gain and the development of obesity, have been disappointing. Weight gain prevention interventions have compared the provision of low-intensity, educational interventions (e.g., monthly mailings with optional educational classes) with no intervention among adults 25 to 74 years of age (6) and 20 to 45 years of age (7,8). Although these trials successfully prevented small amounts of weight gain in the short term (6), long-term results have been discouraging (8). For example, in the Pound of Prevention Study (8,9), minimal treatment did not prevent weight gain over time, and 63% of the participants gained weight over the 3-year study period. The Pound of Prevention intervention was, however, associated with improvements in some weight-related behaviors, suggesting that it is possible to teach individuals about behaviors associated with weight gain prevention.

Moreover, weight gain prevention efforts might have their greatest impact on obesity prevalence by targeting individuals at high risk for weight gain (10). Young adult women are a group at risk for future obesity and an important target for weight gain prevention for several reasons. First, several studies have reported weight increases during young adulthood (11,12). The negative effects of weight gain on health are apparent regardless of an individual's obesity status, and small weight gains among normal-weight young women are associated with increases in coronary heart disease and hypertension later in life (13,14). Second, pregnancy (15,16) and cohabitation or marriage (17-19) have been related to weight gain for young women. Finally, lifestyle approaches have been shown to successfully prevent weight gain among another group of women at high risk for weight gain. The Women's Healthy Lifestyle Project (20) tested the efficacy of a lifestyle intervention among women in the menopausal period, a high-risk period for weight gain (21). In this study, 55% of women who received a lifestyle intervention involving modest weight reduction goals (e.g., losing 5 lbs for a normal-weight woman), increasing physical activity, and decreasing dietary fat and cholesterol, maintained their weight over a 4.5-year period, compared with only 26% of women in a no-treatment control group (22).

Given the increase in rates of obesity, the need for interventions designed to prevent weight gain, and the evidence that women of childbearing age are at particularly high risk for weight gain and future obesity, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine the efficacy of a clinic-based treatment and a correspondence course relative to an information-only control condition in preventing weight gain among women 25 to 44 years of age. In addition, we sought to identify demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial factors related to weight stability.

Research Methods and Procedures

Subjects

Participants were recruited through local television, radio, and newspaper advertisements, direct-market mailings, and announcements to employees of a local medical center. Women responding to advertisements were interviewed by telephone, and those meeting preliminary eligibility criteria were invited to an initial screening visit. To be eligible for the study, women were required to be between 25 and 44 years of age, be in good health according to a self-report questionnaire, and have BMI between 21 and 30.

Women were excluded from participation if they were currently pregnant, had been pregnant or participated in a weight loss program in the past year, were receiving treatment for a psychiatric disorder, had taken a medication affecting body weight during the past 3 months, or were planning to relocate within the next 36 months. In addition, women who were unable to engage in moderate physical activity or make modest changes in dietary intake were excluded. These exclusion criteria were chosen to ensure that the sample would be healthy and to avoid confounds such as weight loss or gain subsequent to recent intervention or medication.

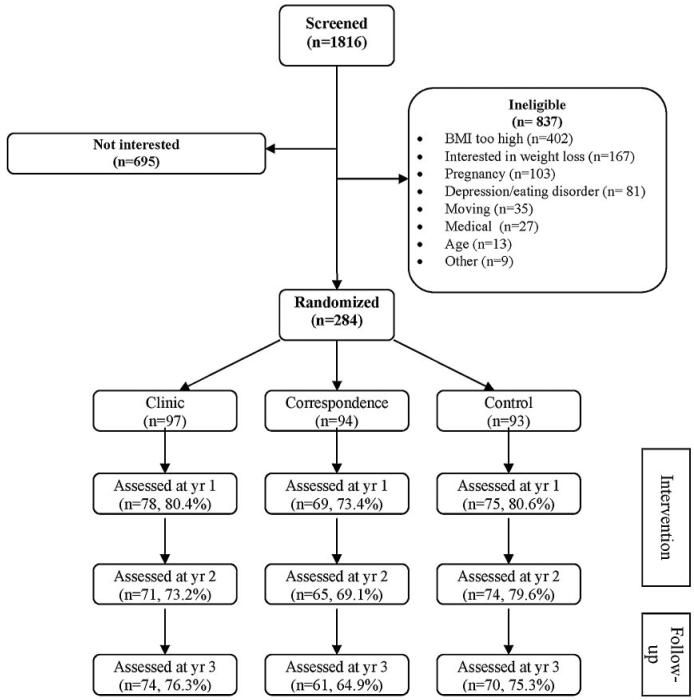

As shown in Figure 1, 1816 women responded to advertisements and were screened for participation, and 1532 were not interested or were ineligible. The most common reason women were ineligible for participation was obesity, with 48.0% of interested callers having a BMI > 30. Thus, a total of 284 were randomized to one of the three conditions. On average, participants were 35.6 ± 5.7 years old, had a BMI of 25.1 ± 2.3, weighed 68.5 ± 8.3 kg, were married (63.1%), were college graduates (64.3%), and were employed outside the home (89.8%). Eighty-six point eight percent were white.

Figure 1.

Study recruitment and flow chart.

Procedures

Women attended an information session during which the three study conditions were described, height and weight were measured, and BMI was calculated (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). Participants also completed assessments of demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial factors. All women signed consent forms approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Participants then were randomly assigned to one of three conditions, a clinic-based group intervention (Clinic),1 a correspondence course (Correspondence), or an information-only control condition (Control). For women randomized to Clinic or Correspondence, intervention was provided over a 2-year period, and women in all three conditions participated in yearly assessments, during which demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial measures were completed.

Intervention Conditions

Interventions were based on the hypothesis that increases in body weight can be prevented by regular (i.e., weekly) monitoring of weight and the use of modest dietary and physical activity changes to offset small increases in weight. Thus, women in the Clinic and Correspondence conditions were given the goal of maintaining their baseline weights for the duration of the study. To help women distinguish a true weight gain from a transient weight fluctuation, weight gain was defined as an increase of 2 lbs (0.91 kg) or more that was maintained for 2 or more consecutive weeks.

Clinic

Participants randomized to the clinic-based group intervention attended 15 group meetings over a 24-month period. On average, attendance at the group meetings was 50.3% across the 15 sessions. Sessions were led by trained nutritionists and behavioral interventionists and were held biweekly for the first 2 months and bimonthly for the next 22 months. Biweekly lessons focused on self-monitoring of energy intake and expenditure and behavioral strategies for making modest changes in dietary intake (e.g., substitution of low-fat foods for high-fat versions) and activity level (e.g., using stairs rather than elevators). Participants also received written information on nutrition and physical activity topics and were directed to set goals for activity and intake. The activity goal was designed to decrease sedentary behavior (e.g., television watching) and increase activity levels. Thus, women were given a recommendation to gradually increase their caloric expenditure to 1000 to 1500 cal/wk. Women also were given intake goals for calories (1100 to 1600, dependent on current weight) and fat (36 to 53 grams, dependent on current weight) to implement if a weight gain of more than 2 lbs occurred. At each biweekly lesson, women were given a homework assignment to practice various weight control strategies before the next lesson. During the 11 bimonthly clinic-based meetings, participants received lessons on cognitive change strategies, stimulus control techniques, problem solving, goal setting, stress and time management, and relapse prevention.

At each meeting, participants were weighed, and if a participant's weight had increased 2 or more lbs over her baseline weight, she met individually with a project interventionist. During this individual meeting, behavioral strategies to encourage modest changes in dietary intake and physical activity were discussed, and a second individual meeting was scheduled for approximately 4 weeks later. This second contact was in a format convenient for the participant (e.g., in-person or by telephone) and focused on reviewing efforts at behavior change since the weight gain was observed. Participants who had returned to baseline weight were encouraged to maintain their weight and received no further individual contact unless another weight gain occurred. Participants who had not returned to baseline weight were provided with further suggestions for refining behavior change efforts. Progress of these individuals was assessed at the next bimonthly group meeting, and additional individual contact with project staff was scheduled as needed.

Correspondence

Participants randomized to the correspondence course received 15 lessons by mail over a 24-month period. The lessons were identical in content to those distributed to participants in the Clinic group and contained a brief homework assignment to be completed by the participant and returned by mail. As part of each homework assignment, participants were asked to weigh themselves and report their weight on their returned assignment. On average, participants returned 38.4% of these homework assignments.

Beginning with the start of bimonthly mailings, a participant whose completed assignment indicated maintenance of baseline weight was sent a brief letter of congratulations and encouraged to maintain healthy eating and exercise behaviors. Participants who reported a weight increase of 2 lbs or more received a letter addressing a weight control topic and encouraging modest changes in eating and activity. These women also were asked to complete and return a self-monitoring postcard on which current estimated energy intake and expenditure were reported and behavior change strategies utilized were endorsed. If a participant reported in subsequent assignments that she had returned to baseline weight, she received a letter of congratulations and encouragement to maintain her healthy habits. If she continued to report a weight increase, she received additional letters encouraging her to self-monitor, use behavioral strategies to decrease energy intake and increase expenditure, and complete and return self-monitoring postcards.

Information-only Control Condition (Control)

At the baseline assessment, individuals randomized to the control group received a booklet containing information about the benefits of weight maintenance, low-fat eating, and regular physical activity (23).

Assessments

Demographic Information

Women provided information regarding age, education, race, ethnicity, number of children, and marital status and information about current or past smoking and other demographic variables.

Intervention Preference

After hearing a brief description of each program during an orientation meeting, women were asked to rate their willingness to participate in each of the three conditions on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 8 (very much so).

Body Weight and Height

At the initial, baseline session and each follow-up assessment, women were weighed using either a portable digital scale (Seca, Hanover, MD) or a balance beam scale (Detecto, Webb City, MO). Height was measured at the baseline assessment using a mounted stadiometer, and BMI was computed (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Three-factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ)

This questionnaire is a measure of habitual dietary behavior. The TFEQ has good internal consistency in community samples (24). There are three empirically derived factors: the restraint factor reflects conscious thoughts and purposeful behaviors to control food intake, the disinhibition factor reflects a tendency to relinquish control over food intake in response to environmental or emotional stimuli, and the hunger factor reflects a susceptibility to experiences of hunger.

Paffenbarger Activity Questionnaire

The Paffenbarger Activity Questionnaire (25) is a commonly used, validated self-report assessment of physical activity. Participants rate both the frequency and duration of walking, stair climbing, and recreational activities performed in the past week. Weekly caloric expenditure is calculated by adding calories expended in physical activity to those expended in exercise of light, moderate, or heavy intensity.

Stress and Depressive Symptoms

Subjects completed the short form of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). The PSS measures the degree to which one perceives life as stressful and has been shown to correlate with life event scores, physical symptomatology, and use of health services (26). Subjects also completed the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; 27) to assess depressive symptomatology.

Data Analysis

The effectiveness of participant randomization was verified using ANOVA or χ2 tests for continuous and categorical baseline variables, respectively. Follow-up Student's t tests or χ2 tests were used to compare two groups when significant differences between group effects were noted. To examine attrition rates across the three conditions, the proportion of women in each condition attending the yearly visit was evaluated using a χ2 test. Women who completed follow-up assessments were compared with those who did not using Student's t tests for continuous and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

The first study aim concerned the efficacy of the intervention conditions, and we evaluated the efficacy of the three study conditions using generalized estimating equations to model outcome over time using all available data. We tested the relative efficacy of Clinic and Correspondence to Control on weight, BMI, and dietary behavior across all 3 years. We also tested two separate models for weight change, one that compared the three groups during the 2 years during which the intervention occurred and one that included only the follow-up period. To address questions about the effect of weight gain prevention interventions among women who were normal vs. overweight at the start of the trial, we divided the sample into two groups on the basis of pre-treatment BMI (normal weight, BMI ≤ 25 vs. overweight, BMI > 25) and examined the efficacy of intervention using generalized estimating equations to model BMI over time by study condition for normal and overweight women separately. Next, women were divided according to weight change at Year 3 into three groups: those who had lost more than 2 lbs (n = 79), those who remained within 2 lbs of their baseline weight (n = 35), and those who had gained more than 2 lbs (n = 170). Women who had lost more than 2 lbs and those within 2 lbs were considered weight stable (n = 114). Using an intent-to-treat approach, women for whom no weight information was available were considered as weight unstable, that is, as having gained. The study was designed to detect, at 80% power and α at 0.05, a 12% difference between either the clinic or correspondence condition and control in the percentage successful at weight gain prevention. χ2 Tests were used to examine the effects of intervention on weight stability.

The second aim of the study was to examine correlates of weight stability over time. For these analyses, women were again divided into two groups (stable vs. gain) according to weight change at Year 3. Stable and gain groups were compared on baseline and change variables using Student's t tests for continuous and χ2 tests for categorical variables, collapsing across intervention conditions. Logistic regressions, controlling for intervention condition and baseline weight, were then used to examine both baseline and change scores (from baseline to Years 2 and 3) as correlates of weight stability. All p values were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Participant Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, women did not differ in age, weight, marital status, dieting status, or psychosocial variables at the start of intervention. However, there were significant differences in educational level and employment status. Women assigned to the Clinic group were significantly less likely to have a college education (χ2 [1] = 8.9, p = 0.003) or to be employed (χ2 [1] = 6.3, p = 0.01) than were those in the other two groups. Because of these differences, education and employment level were entered as covariates in all analyses concerning the effects of intervention. Women's preferences for the three different intervention options were similar for women assigned to each of the three groups.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by intervention condition*

| Clinic (n = 97) |

Correspondence (n = 94) |

Control (n = 93) |

p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age (yrs) | 36.4 | 5.7 | 35.0 | 6.1 | 35.4 | 5.3 | 0.24 |

| BMI | 25.1 | 2.3 | 25.1 | 2.4 | 25.0 | 2.3 | 0.95 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.4 | 8.4 | 69.5 | 8.6 | 67.5 | 7.9 | 0.28 |

| PSS | 8.5 | 1.3 | 8.6 | 1.1 | 8.5 | 1.4 | 0.86 |

| CES-D | 9.5 | 6.9 | 10.8 | 8.2 | 11.4 | 8.8 | 0.26 |

| Restraint | 9.0 | 3.9 | 8.8 | 4.2 | 8.9 | 4.5 | 0.96 |

| Disinhibition | 8.5 | 3.6 | 9.4 | 3.2 | 8.7 | 3.5 | 0.25 |

| Hunger | 6.0 | 3.8 | 6.5 | 3.4 | 6.2 | 3.5 | 0.63 |

| Physical activity (kcal/wk) | 1976 | 1679 | 1527 | 1248 | 2014 | 2424 | 0.14 |

| % | N | % | N | % | N | ||

| Race (white) | 85.4 | 82 | 89.4 | 84 | 85.7 | 78 | |

| Race (black) | 14.6 | 14 | 10.6 | 10 | 14.3 | 13 | 0.67 |

| Family income > $40,000 | 63.4 | 59 | 67.4% | 62 | 64.8 | 59 | 0.85 |

| Married | 68.1 | 64 | 58.5 | 55 | 62.6 | 57 | 0.40 |

| College graduate | 52.6 | 51 | 74.5 | 70 | 66.3 | 61 | 0.006 |

| Employed | 83.5 | 81 | 93.6 | 88 | 92.4 | 84 | 0.04 |

| Smokers | 11.8 | 11 | 8.2 | 8 | 5.3 | 5 | 0.67 |

| Currently dieting | 32.3 | 31 | 39.8 | 37 | 23.9 | 22 | 0.07 |

| Gained weight in past year | 42.3 | 41 | 45.7 | 43 | 39.6 | 36 | 0.70 |

SD, standard deviation; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale.

Not all variables have same n due to missing data.

Attrition

The proportion of women completing the study did not differ across the three intervention approaches (χ2 [2] = 3.74, p = 0.15). Overall, 78% completed a weight assessment at Year 1, 74% completed an assessment at Year 2, and 72% completed an assessment at Year 3. Women who completed assessments at follow-up (n = 205) were older (36.4 ± 5.5 vs. 33.5 ± 5.9, p < 0.001) and were more likely to be married (67% vs. 53%, p = 0.03) than those who did not complete follow-up assessments (n = 79). There were no other demographic or psychosocial differences between women who did and did not complete follow-up assessments.

Differential Effects of Intervention Conditions

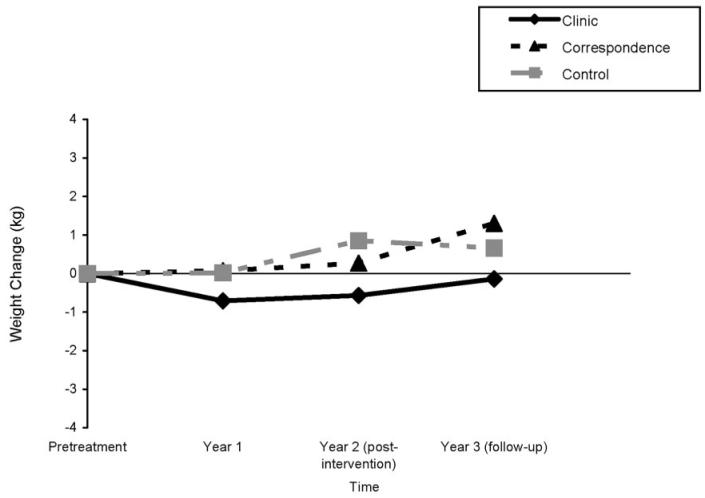

During the 3-year period of study, there were no differences in weight (condition × time, p = 0.37) or BMI (condition × time, p = 0.39) change across the three conditions. There also were no differences across the three conditions in weight (condition × time, p = 0.54) and BMI (condition × time, p = 0.57) change between post-intervention and the 1-year follow-up assessment (p > 0.14). However, as shown in Figure 2, there was a non-significant trend for BMI to decrease more during the 2-year intervention period among women randomized to Clinic (p = 0.10) than in the Correspondence or Control groups. Weight changes post-intervention and at the end of 3-year period were −0.6 (±4.7) and −0.1 (±4.7) kg, respectively, in the clinic group, 0.3 (±4.4) and 1.3 (±5.4) kg, respectively, in the correspondence group, and 0.8 (±5.8) kg and 0.7 (±4.8) kg, respectively, in the control group.

Figure 2.

Weight change over time by intervention condition.

There were no differences in weight change outcome by intervention group when women who were and were not overweight at the start of the study were examined separately. Women with a baseline BMI of 25 or greater (n = 137) gained an average of 0.2 ± 5.2 kg over the 3-year study period, and those with a BMI <25 (n = 147) gained 0.9 ± 4.8 kg. Intervention did not affect weight gain in either group (p > 0.26).

To examine the effect of intervention on weight gain prevention, women who lost more than 2 lbs, remained weight stable (i.e., gained no more than 2 lbs), and gained more than 2 lbs were compared. Overall, 27.8% (n = 79) lost 2 or more lbs over the course of the study (mean weight loss = −3.8 ± 3.1 kg), 12.3% (n = 35) of the women remained within 2 lbs of their initial weight, and 59.9% (n = 170) gained more than 2 lbs (mean weight gain = 4.5 ± 3.9 kg). Thus, 40% (n = 114) were weight stable at Year 3. However, intervention did not relate to successful weight maintenance, with 46.4%, 33.0%, and 40.9% remaining weight stable in the Clinic, Correspondence, and Control groups, respectively (χ2 = 3.6, p = 0.17).

Finally, we evaluated the impact of the interventions on factors associated with weight change. Although intervention condition did not relate to differential weight gain prevention, relative to Control, women randomized to Clinic reported significant changes in dietary restraint. During the period of intervention (i.e., baseline through Year 2), women in the Clinic condition had significant increases in dietary restraint relative to women in the Control and Correspondence groups (β= 0.84, p = 0.005).

Correlates of Weight Stability

As shown in Table 2, several baseline factors related to successful weight gain prevention. Women who were older and felt less hunger as measured by the TFEQ at pre-treatment were more likely to be successful at maintaining their weight. In addition, women who were not on a diet at pre-treatment were more likely to successfully maintain their weight. Specifically, women who self-reported dieting at pre-treatment gained an average of 1.5 (±5.6) kg in 3 years, whereas those not on a diet gained only 0.2 (±4.7) kg.

Table 2.

Differences between women who were and were not successful at weight gain prevention over the 3-year study period

| Stable* (gain ≤ 2 pounds) (N = 114) |

Gain* (gain > 2 pounds) (N = 170) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | ||

| Baseline | |||||||

| Age (yrs) | 36.5 | 5.7 | 35.0 | 5.7 | 0.03 | ||

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 25.0 | 2.4 | 25.1 | 2.3 | 0.79 | ||

| Baseline weight (kg) | 68.0 | 8.6 | 68.8 | 8.1 | 0.41 | ||

| Physical activity (kcal/wk) | 1732 | 1525 | 1920 | 2061 | 0.39 | ||

| Restraint | 8.4 | 3.9 | 9.2 | 4.3 | 0.12 | ||

| Disinhibition | 8.7 | 3.5 | 8.9 | 3.4 | 0.64 | ||

| Hunger | 5.6 | 3.5 | 6.6 | 3.5 | 0.02 | ||

| CES-D | 10.5 | 8.4 | 10.5 | 7.7 | 1.0 | ||

| African American (%) | 11.5 | 14.3 | 0.50 | ||||

| Family income > $40,000 (%) | 68.1 | 63.2 | 0.40 | ||||

| College graduate (%) | 70.2 | 60.4 | 0.09 | ||||

| Employed (%) | 93.0 | 87.6 | 0.14 | ||||

| Currently dieting (%) | 23.9 | 37.5 | 0.02 | ||||

| Gained weight in past year | 42.5 | 42.6 | 0.98 | ||||

| Smoking (%) | 5.2 | 5.7 | 0.68 | ||||

| Change during study period† | |||||||

| Weight (kg) | −2.5 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 3.9 | <0.001 | ||

| Physical activity (kcal/wk) | 158 | 2056 | −223 | 1613 | 0.14 | ||

| Restraint | 2.1 | 3.7 | 0.27 | 3.2 | 0.001 | ||

| Disinhibition | −1.1 | 2.7 | −.03 | 2.6 | 0.012 | ||

| Hunger | −0.5 | 2.9 | −0.5 | 2.4 | 0.99 | ||

| CES-D | 0.70 | 10.5 | 2.9 | 11.2 | 0.15 | ||

SD, standard deviation; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale.

Not all variables have same n due to missing data.

Changes calculated as study end minus baseline, so negative values reflect decreasing characteristic.

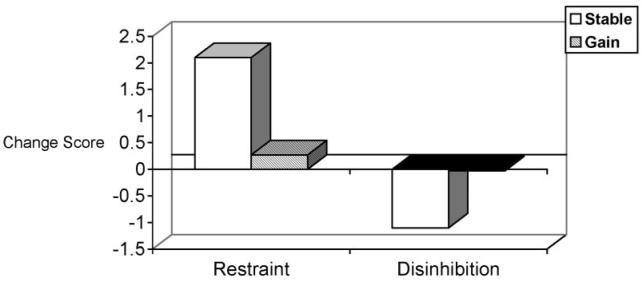

Successful weight maintainers also reported significantly larger increases in restraint and decreases in disinhibition than did women who gained weight over the study period (see Table 2). After controlling for initial BMI, increasing dietary restraint (β = 0.15, p = 0.001) and decreasing disinhibition (β = −0.15, p = 0.01) over the study period remained related to successful weight maintenance (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in dietary restraint and disinhibition by weight stability.

Discussion

Given the considerable morbidity associated with obesity and the dramatic increases in its prevalence among American adults, the development of strategies to successfully prevent weight gain is a critical public health priority. In this randomized clinical trial, we evaluated two approaches to weight gain prevention, bimonthly group meetings at a university clinic and a correspondence course, and found that neither approach was superior to the provision of an information booklet in staving off weight gain among women 25 to 44 years old. These results are particularly discouraging because the interventions were designed to address the needs of a group at risk for future obesity.

This trial was unique in attempting to prevent weight gain in young adult women who were not obese at the start of the study. However, results were similar to findings from previous weight gain prevention programs, particularly the Pound of Prevention trial (8), in which a low-intensity educational intervention did not prevent weight gain among men and women. Thus, even among a homogeneous group at high risk for future obesity and when using a more intensive treatment approach than that used in the Pound of Prevention trial, lifestyle interventions seem to be insufficient to minimize weight gain. Although a larger sample size would improve the power to detect small differences in weight, the between-group differences observed in this trial are of questionable clinical significance (i.e., −0.1 ± 4.7 vs. 1.3 ± 5.4 vs. 0.7 ± 4.8 kg for the Clinic, Correspondence, and Control groups, respectively). Indeed, available evidence suggests that American adults gain an average of ∼1 kg per year (28), and women in this study who were not successful at weight gain prevention (60% of the sample) gained over 4 kg in 3 years. Thus, women in the current study did not seem to benefit from either approach to weight gain prevention tested. This lack of efficacy, coupled with the low adherence rates to the interventions, strongly indicates the need for more intensive strategies to prevent obesity among high-risk groups.

There is evidence to suggest that more intensive approaches may be useful in preventing weight gain among high-risk groups. In the Women's Healthy Lifestyle Project, premenopausal women who received weekly dietary and physical activity lessons were more likely to prevent weight gain during menopause than those who received no intervention (22). Thus, it may be possible to prevent weight gain among high-risk groups, and intensive, structured interventions need to be evaluated among younger women. Given the time and expense associated with intensive interventions, however, it is likely that additional, innovative approaches to the prevention of weight gain will be needed. For example, the Internet has been used successfully as a tool to effect weight loss (29), weight loss maintenance (30), and change in eating attitudes (31) and may be similarly useful in prevention of weight gain.

Although intervention was not differentially associated with weight change in the current study, a considerable number (40%) of women were successful in preventing weight gain during the 3-year study period. Thus, results of the current investigation suggest some factors that may be related to successful weight gain prevention. Women who were successful were less likely to be on a diet and felt less susceptible to feelings of hunger at baseline than were those who gained weight. The self-report of dieting may or may not reflect actual calorie restriction. However, it is likely that the self-report of being on a weight reducing diet indicates difficulties with self-regulation or reflects experience with episodes of weight gain and consequent attempts to control weight. Thus, women who are at risk for weight gain and for whom weight gain prevention efforts will be of greatest benefit may be those who report habitual attempts to self-manage weight, perhaps unsuccessfully.

The TFEQ (24) also distinguished between women who were and were not successful at weight gain prevention. The TFEQ contains three empirically derived factors: restraint, which indicates deliberate efforts to control food intake; disinhibition, which reflects a tendency to relinquish control over food intake in response to internal or external stimuli; and hunger, which reflects a susceptibility to the subjective experience of hunger. At baseline, in addition to self-report of dieting, hunger as measured in the TFEQ predicted a failure to prevent weight gain. Like self-reported dieting, a vulnerability to sensations of hunger may indicate difficulties in self-regulation.

Changes in restraint and disinhibition, also assessed using the TFEQ, were related to successful weight gain prevention. Specifically, women who were successful at preventing weight gain in this study also reported increases in the use of cognitive strategies to self-manage dietary intake. Dietary restraint has been associated with losing weight (32,33) and maintaining weight already lost (34-36). Increasing dietary restraint is also consistent with behaviors prescribed by the intervention (e.g., deliberately taking small helpings or counting calories), and in the Clinic group, women successfully increased their dietary restraint during treatment. Despite initial debate about the connection between weight control behaviors and the development of eating disorder symptoms or the use of unhealthy dietary practices, there is little evidence to suggest that regular monitoring of weight will precipitate disordered or unhealthy eating behaviors (37,38). In fact, regular self-monitoring of body weight is related to lower BMI and increased weight loss in behavioral weight control treatments (39). Thus, dietary restraint may be part of a group of teachable self-regulation strategies in the context of a minimal treatment program.

Similarly, women who remained weight stable during this trial reported decreases in dietary disinhibition or the tendency to lose control over eating. Like restraint, dietary disinhibition has received considerable attention in relation to weight and has been associated with aberrant overeating (40,41) and weight gain (34). Although it is unclear whether increases in disinhibition among women who gained weight in this trial were a cause or consequence of the weight gain, it is possible that monitoring an individual's tendency to lose control over eating behavior will indicate periods of increased vulnerability to weight gain that may be moderated by intervention.

In contrast, demographic differences, with the exception of age, were not related to success at weight gain prevention. Although women who maintained a stable weight over the 3-year study period were, on average, 1.5 years older than those who gained, it is not likely that this difference in age is clinically meaningful. It is also noteworthy that physical activity, which has been shown to improve weight loss and longer term weight maintenance (2,36,42), and smoking cessation, which has been linked to weight gain (43,44), were not related to weight gain prevention in this trial.

Finally, this trial suggests the need to increase the relevance of weight gain prevention among groups at high risk of weight gain. This study was designed to prevent weight gain among normal-weight women 25 to 44 years of age, a group for whom the risk of weight gain is high. However, nearly 40% (695 of 1816, 38%) of the women who were screened for this study were not interested in participating. The study also was originally conceived as a test of weight gain prevention strategies among normal-weight young women (i.e., BMI < 25), but a majority of callers to this university-based weight prevention study were already overweight, and a large proportion of women (68%, see Figure 1) were ineligible for the study either because they were obese or because they were interested in receiving weight loss treatment. Thus, although data from this trial cannot be used to gauge the interest of normal-weight women relative to their overweight or obese peers, it does provide anecdotal evidence that weight gain prevention may not be salient among normal-weight women and suggests that messages to promote the importance of weight gain prevention among women need to be developed. Perhaps advances in genetic research also will help identify individuals vulnerable to future weight gain. For example, recent evidence highlights the possible roles of the glucocorticoid receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor genes in the maintenance of lost weight (35), and it may be that increased understanding of genetic factors related to successful weight maintenance will help to improve efforts at weight gain prevention among individuals at high risk for weight gain and future obesity.

In summary, despite increasing recognition of the need to prevent obesity, weight gain prevention is a challenging task. The results of this trial indicate that neither a bimonthly group meeting nor a correspondence course was superior to the receipt of a booklet in preventing weight gain. However, age, dieting status, and feelings of hunger were related to weight gain. Strategies to increase the salience of preventing weight gain and effective interventions to prevent obesity need to be developed, and stronger public health messages advocating regular self-monitoring of weight or exercising greater dietary control may be necessary to prevent the development of obesity among adults.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Grants DK 053942 (to M.D.M.) and K01 DA15396 (to M.D.L.) and by the Pittsburgh Obesity and Nutrition Research Center (Grant DK046240). The study sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. We thank Donielle Neal, Meghan Wisinski, and Alison Keating for assistance with data collection and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations: Clinic, clinic-based group intervention; Correspondence, correspondence course; Control, information-only control condition; TFEQ, Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale.

References

- 1.Brownell KD, Wadden TA. Etiology and treatment of obesity: understanding a serious, prevalent, and refractory disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:505–17. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19(suppl):5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Byrne KJ. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. Obes Res. 2004;12(Suppl):151–62S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumanyika S, Jeffery RW, Morabia A, Ritenbaugh C, Antipatis VJ. Obesity prevention: the case for action. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:425–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The National Task Force on Prevention and Treatment of Obesity Towards prevention of obesity: research directions. Obes Res. 1994;2:571–84. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forster JL, Jeffery RW, Schmid TL, Kramer FM. Preventing weight gain in adults: a pound of prevention. Health Psychol. 1988;7:515–25. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.6.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeffery RW, French SA. Preventing weight gain in adults: design, methods and one year results from the Pound of Prevention study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:457–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeffery RW, French SA. Preventing weight gain in adults: the Pound of Prevention Study. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:747–51. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French SA, Jeffery RW, Murray D. Is dieting good for you? Prevalence, duration and associated weight and behaviour changes for specific weight loss strategies over four years in US adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:320–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in Medicine. Little, Brown and Company; Boston, MA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis CE, Smith DE, Wallace DD, Williams OD, Bild DE, Jacobs DR., Jr Seven-year trends in body weight and associations with lifestyle and behavioral characteristics in black and white young adults: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:635–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheehan TJ, DuBrava S, DeChello LM, Fang Z. Rates of weight change for black and white Americans over a twenty year period. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:498–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Z, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, et al. Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. JAMA. 1997;278:1407–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Z, Willet WC, Manson JE, et al. Body weight, weight change, and risk for hypertension in women. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:81–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rooney BL, Schauberger CW. Excess pregnancy weight gain and long-term obesity: one decade later. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:245–52. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williamson DF, Madans J, Pamuk E, Flegal KM, Kendrick JS, Serdula MK. A prospective study of childbearing and 10-year weight gain in US white women 25 to 45 years of age. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994;18:561–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson AS, Marshall DW, Lea EJ. Shared lives-an opportunity for obesity prevention? Appetite. 2004;43:327–9. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeffery RW, Rick AM. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between body mass index and marriage-related factors. Obes Res. 2002;10:809–15. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobol J, Rauschenbach B, Frongillo EA. Marital status changes and body weight changes: a US longitudinal analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1543–5. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, Hansen DH, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular risk factor elevations in healthy premenopausal women. Prev Med. 1995;24:509–17. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wing RR, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Meilahn EN, Plantinga PL. Weight gain at the time of menopause. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, Boraz MA, Kuller LH. Lifestyle intervention can prevent weight gain during menopause: results from a 5-year randomized clinical trial. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:212–20. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koop CE. On Your Way to Fitness: A Practical Guide to Achieving and Maintaining Healthy Weight and Physical Fitness. Connecticut Marketing Associates, Inc.; Wilton, CT: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paffenbarger RS, Wing AL, Hyde RT. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:161–75. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winett RA, Tate DF, Anderson ES, Wojcik JR, Winett SG. Long-term weight gain prevention: a theoretically based internet approach. Prev Med. 2005;41:629–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. Effects of internet behavioral counseling on weight loss in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1833–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harvey-Berino J, Pintauro SJ, Gold EC. The feasibility of using internet support for the maintenance of weight loss. Behav Modif. 2002;26:103–16. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Celio AA, Winzelberg AJ, Wilfley DE, et al. Reducing risk factors for eating disorders: comparison of an internet- and a classroom-delivered psychoeducational program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:650–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Swain RM, Anderson DA, Vogt RA. Changes in resting energy expenditure after weight loss in obese African American and white women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:13–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Womble LG, Williamson DA, Greenway FL, Redmann SM. Psychological and behavioral predictors of weight loss during drug treatment for obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:340–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Hill JO. Behavioral strategies of individuals who have maintained long-term weight losses. Obes Res. 1999;7:334–41. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogels N, Mariman ECM, Bouwman FG, Kester ADM, Diepvens K, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Relation of weight maintenance and dietary restraint to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma2, glucocorticoid receptor, and ciliary neurotrophic factor polymorphisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:740–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.4.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:323–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Kendall PC, Stunkard AJ, Vogt RA. Psychological effects of weight loss and regain: a prospective evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:752–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.French SA, Jeffery RW. Consequences of dieting to lose weight: effects on physical and mental health. Health Psychol. 1994;13:195–212. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linde JA, Jeffery RW, French S, Pronk NP, Boyle RG. Self-weighing in weight gain prevention and weight loss trials. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:210–6. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcus MD, Wing RR, Hopkins J. Obese binge eaters: affect, cognitions and response to behavioral weight control. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:433–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Telch CF, Stice E. Psychiatric comorbidity in women with binge eating disorder: prevalence rates from a non-treatment-seeking sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:768–76. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donnelly JE, Hill JO, Jacobsen DJ, et al. Effects of a 16-month randomized controlled exercise trial on body weight and composition in young, overweight men and women: the Midwest Exercise Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1343–50. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williamson DF, Maddans J, Anda RF, Kleinman JC, Giovino GA, Byers T. Smoking cessation and severity of weight gain in a national cohort. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:739–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103143241106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klesges RC, Winders SE, Meyers AW, et al. How much weight gain occurs following smoking cessation? A comparison of weight gain using both continuous and point prevalence abstinence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:286–91. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]