Abstract

The aim of the study was to see if delay in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction affects post-reconstruction outcome in recreational athletes. Sixty-two recreational athletes who had arthroscopic ACL reconstructions using quadruple hamstring grafts between 1997 and 2000 were retrospectively evaluated. Patients with less than 2 years’ follow-up, those with multi-ligament injuries, reconstructions for previous failed repairs, those whose injury date was unknown, those with pre-injury Tegner activity level greater than 7 (competitive athletes) and those lost to follow-up were all excluded. Forty-six patients (38 males) were entered. The mean follow up was 38 months and the mean time from injury to index ACL reconstruction was 27 months. Apart from two revisions there were no other significant complications. Forty-one (89%) patients were evaluated in a review clinic. There was a significant improvement in the post-reconstruction Lysholm scores and an improvement in the Tegner scores. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient between postoperative Lysholm score and the delay until surgery was −0.18 and the correlation coefficient between postoperative Tegner scores and the delay until surgery was 0.14. Thirty-five patients returned to sporting activity. Thirty-seven rated their knee as being normal or nearly normal and 35 said that their knee function was as they had expected it to be. Late ACL reconstruction does not adversely affect the outcome in recreational athletes. ACL reconstruction should be offered to these patients as there is a significant improvement in the knee function and patients are satisfied with the results.

Résumé

Le but de cette étude est d'analyser les résultats d'une reconstruction du ligament croisé antérieur retardée chez les sportifs de loisir. Soixante-deux sportifs de loisir ont eu une réparation arthroscopique du ligament croisé antérieur en utilisant les muscles de la patte d'oie, entre 1997 et 2000. Il s'agit d'une étude rétrospective. Ont été exclus de cette étude les patients qui ont moins de deux ans de recul et/ou avec de nombreuses lésions ligamentaires, la réparation du ligament croisé antérieur secondaire à un échec d'intervention antérieure et ceux dont on ne connaissait pas la date exacte du traumatisme initial. Ont été également exclus les athlètes de compétition (7) et les patients perdus de vue. Quarante-six patients (38 de sexe masculin) ont été analysés, le suivi moyen a été de 38 mois et le délai moyen entre le traumatisme initial et la réparation du ligament croisé antérieur a été de 27 mois. En dehors de deux reprises, il n'y a pas eu de complications significatives. Quarante et un (89%) patients ont été évalués cliniquement lors de la revue. Le score de corrélation de Spearman mettant en relation le score de Lysholm post-opératoire et le délai moyen d'intervention a été de −0,18 de même en ce qui concerne le coefficient de corrélation post-opératoire de Tegner et le délai moyen de l'intervention donnant un résultat à 0,14. Trente-cinq patients ont repris leurs occupations sportives. Trente-sept ont estimé que leur genou était redevenu normal ou presque normal et 35 ont estimé que le résultat sur la fonction était celui qu'ils attendaient. Chez les athlètes de loisir une réparation tardive du ligament croisé antérieur n'affecte pas l'avenir du genou, la reconstruction du ligament croisé antérieur entraîne pour ces patients une amélioration significative de la fonction du genou et les patients sont très satisfaits du résultat.

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction has satisfactory results and is the best treatment option for a young population participating in competitive sports [1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 16]. Various factors affecting the final outcome following reconstruction include the preoperative Tegner activity level of the patient [5, 9], the age of the patient [2, 15], the time of reconstruction (acute versus subacute) [6, 7, 10, 12, 17, 18] and the associated multiple ligament injuries.

Controversy exists over the most suitable time for reconstructing the ACL after injury. Reconstruction within 2 weeks of the injury [20] has been recommended by a few authors. Early surgical treatment may help prevent increased instability of the knee and reduces the risk of meniscal and chondral injuries [10, 11, 14]. Other studies, however, found the results of early reconstruction unpredictable due to problems such as deficit of motion, pain, arthrofibrosis and patellar contracture syndrome [6, 17, 18]. They recommended reconstruction at least 3 weeks after injury. In most of these studies the patients were competitive athletes (pre-injury Tegner activity level >7) [7, 10]. Not many studies comment on the outcome of late reconstruction in recreational athletes (pre-injury Tegner activity level <7) [9].

The aim of this study was to see if the delay until surgery affected the outcome after ACL reconstruction in recreational athletes.

Patients and methods

The study was conducted in a University hospital setting. Patients who had arthroscopic ACL reconstruction by the senior author (SPG) in the period 1997 to 2000 were included. Patients with less then 2 years’ follow-up at last clinical review, with multi-ligament injuries, undergoing ACL reconstruction for previous failed repairs, patients with pre-injury Tegner activity level greater than 7 (competitive athletes) and those lost to follow-up were all excluded.

Patients who had persistent clinical instability after an intensive ACL-deficient rehabilitation program were offered surgery. The delay in surgery was due to a late referral of patients to the senior author by either the A & E, the GP, or other orthopaedic surgeons for various reasons and was not intentional.

Patients had arthroscopic ACL reconstruction using quadruple hamstring grafts. A variety of femoral and tibial anchoring devices were used. Patients used a knee brace postoperatively and a standard rehabilitation program was used in all the patients.

The data recorded included the exact date of original injury; pre-injury sports activity level, preoperative Lysholm and Tegner scores, type of graft used for reconstruction, method of fixation of the graft and complications after the reconstruction. At final review we recorded the post-reconstruction Lysholm and Tegner scores, patient satisfaction with the surgical treatment, return to sporting activity and work.

Data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and statistical analysis was performed using an SPSS package. We assessed improvement in knee function following surgery and tested for significance in improvement using paired t test. A Spearman’s correlation analysis was carried out between post-reconstruction scores achieved and improvement in the post-reconstruction scores with the interval between injury to surgery. To perform a power analysis we assumed the null hypothesis that there was a weak correlation between the post-surgical recovery and delay until surgery. To disprove this and show a strong correlation of, say, 0.7 we would need about 20 participants in the study.

Results

Sixty-two patients were included. After exclusion we had 46 patients, 38 males and eight females. The average age was 30 (range 17–47) years and the average follow-up was 38 months (range 2–5 years). There were five patients who were lost to follow-up and were excluded. Of these, three were referred to other facilities for follow-up as they had moved home, one decided to be treated elsewhere because of an unsatisfactory result, and no data were available about the last patient.

The mean delay from injury to index surgery was 27 (range 5–144) months. Table 1 shows the different times at which the index surgery was performed and it highlights the fact that a majority of patients in this group had very late reconstructions. Quadruple hamstring graft was used in all. An interference screw was used in 41 patients, suture disc was used in two and a tibial cradle in three. On the femoral side the transfix screw was used in 30, the endo-button in seven and an interference screw in nine.

Table 1.

Time of index surgery interval since original injury

| Time since Injury (months) | Number of patients operated |

|---|---|

| 5–12 | 5 |

| 12–18 | 6 |

| 18–24 | 9 |

| >24 | 21 |

In two patients the reconstructions failed and were awaiting revision surgery. Besides the failures eight complications were noted in six patients. In five patients there were problems with the anchoring device (tibial device in four and femoral device in one), which had to be removed. Two patients had persistent mild pain and synovitis.

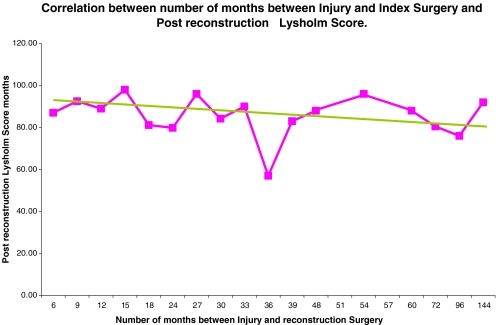

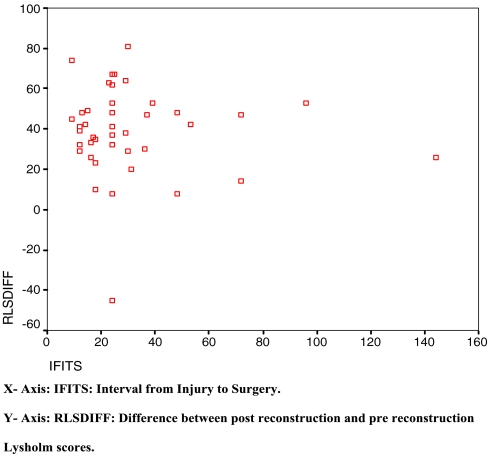

Forty-one (89%) patients were evaluated at final review. The average pre-injury activity level of the cohort was 5.9 (range 3–7).The average post-injury and post reconstruction Lysholm score was 47.1 (range 16–70) and 84.76 (range 32–99) respectively. The mean improvement was 37.4 (95% CI 30.66, 44.1). The change was statistically significant using the paired t test (p=0.001).The post-reconstruction Lysholm score was correlated with the delay until surgery. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was −0.182. We also correlated the improvement in scores achieved against the delay until surgery. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was −0.015. The scatter plots shown in Figs. 1 and 2 do not show any trend towards a negative correlation.

Fig. 1.

Correlation scatter plot between post-reconstruction Lysholm score and interval between injury and surgery

Fig. 2.

Correlation scatter plot between the difference between post- and pre-reconstruction Lysholm scores and the interval between injury and surgery

The average post-injury and post-reconstruction Tegner score was 2.97 (range 1–6) and 5.12 (range 3–8) respectively. The mean improvement was 2.09 (95% CI 1.52, 2.65). This change was statistically significant with a paired t test (p value below 0.001).The post-reconstruction Tegner score achieved was correlated with delay until surgery. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was 0.14. We also correlated the improvement in scores after surgery with delay until surgery. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was 0.061. The scatter plots shown in Figs. 3 and 4 also do not show a negative correlation.

Fig. 3.

Correlation scatter plot between post-reconstruction Tegner score and interval between injury and surgery

Fig. 4.

Correlation scatter plot between the difference between post- and pre-reconstruction Tegner scores and the interval between injury to surgery

Patients were asked to rate their satisfaction with the surgery. Twenty-four said the knee was better then expected and 12 said that it was as they had expected it. Five patients said it was not as good as they had expected it to be. Two of these were the patients whose reconstruction had failed and three were those who had persistent postoperative pain. Patients were asked to rate their knee and eight said it was normal, 30 said it was nearly normal and three said it was abnormal. The patients who rated their knee poorly correlated well with the failures and those who had postoperative complications.

A meniscal injury was found in 18 patients either at diagnostic arthroscopy or at index surgery. The tear was repaired in six, but in five of these it had to be excised at a second operation. In 23 no meniscal injury was seen. The average post-reconstruction Lysholm score achieved was 84.71 (range 21–97) and 84.44 (31–97) in patients with and without a meniscal tear respectively. Similarly, the average post-reconstruction Tegner score achieved was 5.09 (range 2–8) and 4.96 (range 3–8) in patients with and without meniscal tear respectively.

Discussion

The best time for ACL reconstruction is a subject of debate. Very early surgery runs the risk of inducing arthrofibrosis and can produce unpredictable results [6, 17, 18], which affect the range of movement achieved [13]. Late surgery carries the risk of increasing the chance of having a meniscal or chondral injury [11, 12, 14].

Marcacci et al. [12] compared a group who had very early reconstruction, within 15 days of injury, versus those who had surgery more than 3 months after injury. They found that the results were better in the group treated early, which had more stable knees, less chance of having associated injuries and a higher percentage of return to sport at the preoperative level. They conclude that irrespective of the technique used early ACL reconstruction should be advocated in young patients with high professional motivations to prevent secondary injuries without the risk of loss of motion. The main drawback of the study is the use of an objective outcome measure like the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score. The use of functional outcome measurements that are partially based on joint laxity measures such as the IKDC form may artificially overestimate the disability after ACL rupture [19].

Another study [10] comparing the results of reconstruction performed sub-acutely (2–12 weeks) versus that performed late (12–24 months) in competitive athletes found no difference in the Lysholm scores, IKDC scores, the patients’ subjective evaluation and the one leg hop test in both groups. However, the authors did find that the patients operated on earlier had a higher activity level and a higher desired activity level 2–5.5 years after index surgery. Furthermore, meniscal injuries were more common if the reconstruction was delayed. In this group the maximum delay in surgery was 2 years post-injury. Similarly, Goradia and Grana [7] concluded that hamstring tendons are an excellent graft choice in both acute and chronic injuries. More than 90% of patients can be expected to have normal or nearly normal knees at follow-up; however, the chronic group will have fewer patients with a knee rating of normal. They also found a higher incidence of meniscal injuries in the chronic group. Meighan et al. [13] in a randomised control trial comparing acute versus sub-acute repair found no difference in the outcome. However, they found a decreased ultimate range of motion in the acute group as well as decreased quadriceps strength. In all these studies the patients were competitive athletes or had high professional motivations (pre-Injury Tegner activity level >7) [9, 10].

There are not many studies that look at outcome in recreational athletes following surgery and the best treatment for recreational athletes is still disputed [9, 15]. Patients with a pre-injury Tegner activity level of 7 or above are defined as professional athletes [10]. Jerre et al. [9], however, classed people with Tegner activity levels of 9–10 as competitive athletes.

Jerre et al. [9] compared the outcome in recreational athletes (pre-injury Tegner score 2–5) versus competitive athletes (pre-injury Tegner score 9–10). The differences in the Lysholm scores, IKDC scores and the subjective evaluation were not significant; however, the authors did notice a significantly higher reduction in Tegner activity level in the competitive athletes. They concluded that ACL reconstruction should be recommended for both recreational and competitive athletes. In this study the mean time period between injury and index surgery was 24 (range 3–360) months in the recreational athletes and 12 (range 2–168) months in the competitive athletes. An increased incidence of meniscal injury was not noticed in either group, especially in the group of recreational athletes who were operated upon quite late after their original injury. Novak et al. [15], in 19 recreational athletes over the age of 35 who had delayed reconstruction, reported results comparable to a younger population.

The principle findings in our study were an improvement in the Lysholm and Tegner scores after reconstruction at medium term follow-up. There was no negative or positive correlation between the functional outcome and the delay until surgery. Eighty-five percent rated their outcome as either better than expected or as expected. Ninety-one percent of the patients rated the knee as normal or nearly normal and 70% returned to some sporting activity. The knee scores achieved in patients with or without meniscal injury were the same. In most previous studies the ACL reconstruction has been performed in high activity athletes and very little is known about outcomes in recreational athletes. Our cohort is similar to the group of recreational athletes in the study by Jerre et al. [9] and the average age in our study was 30 years compared with 35 years for recreational athletes in their study.

In our study all the patients are recreational athletes. They all had delayed surgery after failed conservative treatment (5–144 months), more than 24 months after injury in more than half of them. The delay in surgery, as pointed out previously, was not intentional. The strengths of our study are reasonable patient numbers, follow-up observations were uniform and made by an independent observer not involved in the original surgical procedure or rehabilitation, a strong statistical input, and all the procedures were performed by one surgeon. The potential weakness is the retrospective nature of the study; some information has been collected in the form of an audit, and the use of different tibial and femoral fixation devices. We have moreover been unable to assess if this accidental delay increased the risk of associated meniscal injury. Jerre et al. [9] did not have any such finding in their study.

Recreational athletes are different from competitive athletes and hence should be considered separately when planning treatment. We conclude that a delayed reconstruction in recreational athletes with ACL insufficiency presenting late with clinical instability does not adversely affect outcome. A long delay in presentation to a specialist should not be a factor in denying the patients surgery as comparable results can be achieved in this cohort of patients whose expectations are much less than those of competitive athletes.

References

- 1.Andersson C, Odensten M, Gillquist J (1991) Knee function after surgical or non-surgical treatment of acute rupture of the anterior cruciate: a randomized study with long term follow up period. Clin Orthop 264:255–263 [PubMed]

- 2.Barber FA, Elrod BF, McGuire DA et al (1996) Is an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction outcome age dependent? Arthroscopy 12:720–725 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Casteleyn PP (1999) Management of anterior cruciate ligament lesions: surgical fashion, personal whim or scientific evidence? Study of medium- and long-term results. Acta Orthop Belg 65:327–339 [PubMed]

- 4.Clancy WG Jr, Ray JM, Zoltan DJ (1988) Acute tears of the anterior cruciate ligament. Surgical versus conservative management. J Bone Joint Surg 70A:1483–1488 [PubMed]

- 5.Fink C, Hoser C, Hackl W et al (2001) Long-term outcome of operative or nonoperative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture—is sports activity a determining variable? Int J Sports Med 22:304–309 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fisher SE, Shelbourne KD (1993) Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic extension block complicating anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 21:558–564 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Goradia VK, Grana WA (2001) A comparison of outcomes at 2 to 6 years after acute and chronic anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions using hamstring tendon grafts. Arthroscopy 17:383–392 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hinterwimmer S, Engelschalk M, Sauerland S et al (2003) [Operative or conservative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a systematic review of the literature] (in German). Unfallchirurg 106:374–379 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Jerre R, Ejerhed L, Wallmon A et al (2001) Functional outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in recreational and competitive athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 11:342–346 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Karlsson J, Kartus J, Magnusson L et al (1999) Subacute versus delayed reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament in the competitive athlete. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 7:146–151 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Keene GC, Bieckerstaff D, Rae PJ et al (1993) The natural history of meniscal tears in anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency. Am J Sports Med 21:672–679 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Marcacci M, Zaffagnini S, Iacono F et al (1995) Early versus late reconstruction for anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Results after five years of followup. Am J Sports Med 23:690–693 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Meighan AA, Keating JF, Will E (2003) Outcome after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament in athletic patients. A comparison of early versus delayed surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br 85:521–524 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Millett PJ, Willis AA, Warren RF (2002) Associated injuries in pediatric and adolescent anterior cruciate ligament tears: does a delay in treatment increase the risk of meniscal tear? Arthroscopy 18:955–959 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Novak PJ, Bach BR Jr, Hager CA (1996) Clinical and functional outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the recreational athlete over the age of 35. Am J Knee Surg 9:111–116 [PubMed]

- 16.Roos H, Karlsson J (1998) Anterior cruciate ligament instability and reconstruction. Review of current trends in treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports 8:426–431 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Shelbourne KD, Patel DV (1995) Timing of surgery in anterior cruciate ligament injured knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 3:148–156 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Shelbourne KD, Wilckens JH, Mollabashy A et al (1991) Arthrofibrosis in acute anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The effect of timing of reconstruction and rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med 19:332–336 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Snyder-Mackler L, Fitzgerald GK, Bartolozzi AR III et al (1997) The relationship between passive joint laxity and functional outcome after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med 25:191–195 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Wasilewski SA, Covall DJ, Cohen S (1993) Effect of surgical timing on recovery and associated injuries after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 21:342–388 [DOI] [PubMed]