Abstract

As part of the international campaign of the bone and joint decade, we aimed to present epidemiological data on the prevalence of major joint complaints in a Central European region. Ten thousand subjects aged between 14 and 65, selected randomly by the Hungarian central office of statistics from three counties in southern Hungary, were surveyed using our own questionnaire based on widely accepted scoring systems in the literature, focusing on major degenerative joint complaints, and using the short form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire. We found that the prevalence of hip pain in the observed group was 22.2%, the prevalence of knee pain 30.3%, and frequent ankle pain occurred in 9.7%. The results of the SF-36 questionnaire showed that with the exception of social function, neither of the values of the examined health dimensions reached levels of other international surveys. Details of the survey and the possible causes of the higher prevalence are discussed, along with the results of the SF-36 questionnaire.

Résumé

En collaboration avec la campagne internationale sur la bone and joint decade, notre but a été de mettre en évidence des données épidémiologiques sur la prévalence des lésions articulaires, dans une région du centre Europe. Pour cela, 10.000 patients âgés entre 14 et 65 ans ont été sélectionnés par l’Office Cental Hongrois de Statistiques, patients provenant de trois comtés du Sud de la Hongrie en usant d’un questionnaire, rempli par les patients eux-mêmes et basé sur des scores largement acceptés par la population orthopédique et, notamment, le score SF 36. Nous avons trouvé une prédominance de douleur de la hanche dans ce groupe, avec un taux de 22,8%, le pourcentage de douleur du genou étant de 30,8% et, celle de la cheville, de 9,7%. Les résultats du questionnaire SF 36 ont montré qu’en dehors des problèmes sociaux, les valeurs retrouvées se situaient à des niveaux comparables à ceux d’autres études internationales. Les détails de cette étude et les étiologies possibles sont discutés avec les résultats du questionnaire SF 36.

Introduction

In April 1998 an international multidisciplinary consensus meeting declared the period 2000–2010 to be the “bone and joint decade” with the goal of raising global awareness of the impact of different musculoskeletal disorders. In addition to defining the “status quo,” future goals and perspectives were also underlined. These included epidemiological expectations, new diagnostic approaches, possible preventive measures, therapeutic developments, etc. [13].

Osteoarthritis is one of the major problems affecting our aging populations. It has been estimated that 2–3% of the adult American population suffers from regular pain from osteoarthritis (OA), and approximately one-third of adults in the US between 25–74 years of age have radiological evidence of OA in at least one of the major joints [4]. Another survey, conducted in the UK, showed that 5% of the population over 16 years of age suffers from major joint problems rising to 20% among the 75-year-old population [1]. Other studies showed a prevalence of 25% joint morbidity (hip and knee disease) in people over 60 [12].

The increasing number of joint complaints and radiological OA is matched by the rising number of major joint replacements. It is estimated that in the US alone, the total volume of joint replacement surgery (hip and knee) will increase from 684,000 cases in 2003 to over a million cases in 2013 [11]. In Europe an exponential increase is also expected [2].

The number of publications on this topic is low. To our knowledge, no representative survey has been carried out on degenerative joint complaints in the central European region. Joining the international effort of the “bone and joint decade,” a questionnaire survey involving 10,000 people was carried out. Our aim was to assess the prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms (hip, knee, ankle) and the general musculoskeletal state of health of a representative sample of the Hungarian population.

Patients and methods

Ten thousand individuals aged between 14 and 65 years living in three counties of the southern Transdanubian region of Hungary were involved in the study. According to the 2001 Hungarian census, this region has approximately 995,000 inhabitants, i.e. 9.8% of the Hungarian population. The sample was selected and provided by the Baranya County Division of the Hungarian Central Office of Statistics. The sample was representative with regard to age, employment and municipal structure. Data were obtained via personal interviews by approximately 300 trained pollsters.

Of the population examined 55.1% were women, 44.9% were men, with an average age of 42.1 years. 51% of the people surveyed were employed, 28.4% inactive and 19.4% were unemployed for various reasons (students, pregnant women, etc.) Among the employed people the percentage of physical workers was higher (32% of the total number) than that of the white collar workers (19% of the total number).

Since there is no generally accepted questionnaire for musculoskeletal symptoms and complaints, we used our own questionnaire to explore the prevalence of the diverse degenerative and inflammatory joint complaints. Nevertheless, the questionnaire incorporated questions of standardised, internationally used scores. In order to obtain data on the general physical and mental status of the people examined, they were also asked to fill out the short form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire [15].

Results

Hip

Of the 9,957 surveyed, 2,207 complained of hip pain (22.2%). Forty-three participants did or could not answer the question. Six hundred and ninety-eight (15.6%) were men, 1,509 (27.5%) were women.

The age-related occurence of hip pain is shown in Table 1. Those who gave positive answers were asked to rate their pain on a five-point scale where 1 meant a slight and 5 an unbearable pain. The average value was 3.0759. Typically, in 75.8% the pain occurred as a starting pain with the first steps after getting up from a lying or sitting position. Constant pain was mentioned in 33.4%. Three hundred and fifty-five people had to use some kind of walking aid, mostly one cane (3.55%). Twenty were wheelchair-bound and 20 were bed-ridden.

Table 1.

Age-related occurrence of hip pain

| Age (years) | Hip pain | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | |

| 14–19 | 19 | 639 | 658 |

| 2.9% | 97.1% | 6.6% | |

| 20–29 | 104 | 1,610 | 1,714 |

| 6.1% | 93.9% | 17.2% | |

| 30–39 | 239 | 1,664 | 1,903 |

| 12.6% | 87.4% | 19.1% | |

| 40–49 | 529 | 1,554 | 2,083 |

| 25.4% | 74.6% | 20.9% | |

| 50–59 | 762 | 1,394 | 2,156 |

| 35.3% | 64.7% | 21.7% | |

| 60–65 | 554 | 886 | 1,440 |

| 38.5% | 61.5% | 14.5% | |

Two hundred and fifty-nine persons (2.5%) had had some kind of hip disease during childhood and 150 (1.5%) had already undergone hip operations.

Knee

The prevalence of knee pain in the examined group outnumbered the number suffering from hip complaints. To the question, “have you experienced knee pain recently?” 3,015 persons (30.3%; 1,290 men, 1,725 women) gave a positive answer. Among these, 1,089 suffered from daily knee pain. The average age of those who gave a positive answer (48.2 years) was almost 10 years higher than those who did not have knee pain (39.5 years). When observing the age-specific prevalence of the symptoms, a constant increase from 12% in the youngest age group (14–19) to 47.8% in the oldest (60–65) was seen. The frequency of knee pain changes with age, as can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency of knee pain related to age groups

| Age (years) | How often do you have knee pain? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every day | More than once a week | Once a week | More than once a month | Every 3 months | Once or twice a year | Total | |

| 14–19 | 2 | 23 | 12 | 28 | 8 | 5 | 78 |

| 2.6% | 29.5% | 15.4% | 35.8% | 10.3% | 6.4% | 0.1% | |

| 20–29 | 37 | 59 | 53 | 75 | 22 | 13 | 259 |

| 14.3% | 22.8% | 20.5% | 28.9% | 8.5% | 5.0% | 2.6% | |

| 30–39 | 86 | 98 | 65 | 93 | 28 | 13 | 383 |

| 22.5% | 25.5% | 17.0% | 24.3% | 7.3% | 3.4% | 3.8% | |

| 40–49 | 228 | 172 | 82 | 134 | 26 | 16 | 658 |

| 34.6% | 26.1% | 12.5% | 20.4% | 4.0% | 2.4% | 6.6% | |

| 50–59 | 408 | 218 | 104 | 163 | 28 | 15 | 936 |

| 43.6% | 23.3% | 11.1% | 17.4% | 3.0% | 1.6% | 9.4% | |

| 60–65 | 328 | 136 | 94 | 104 | 16 | 7 | 685 |

| 47.9% | 19.9% | 13.7% | 15.2% | 2.3% | 1.0% | 6.9% | |

The onset of pain was observed mostly immediately after standing up from a sitting position and as a starting pain in 64.2% of those who had knee pain. Almost half of the people surveyed (46.6%) experienced knee crepitus, and 20.9% complained of knee swelling. These symptoms were accompanied by pain in 23% and 16.3% respectively.

Six hundred and fifty-eight (6.6%) people had previously undergone knee aspiration and 956 (9.6%) had been given a knee injection. Six hundred and forty-one (6.4%) had undergone operations for either knee injury (4.2%) or for other (2.2%) conditions.

The approximate prevalence of valgus knee was 19.9% (these people said they could not close their ankles when the two knees were touching each other) and that of varus knee was 18.5%.

Ankle

Two thousand nine hundred and thirty-nine (29.5%) complained of swelling of either ankle. This symptom along with the presence of varices had a female predominance of 2,076 (37.8%) over 863 men (19.3%). Frequent ankle pain was observed in 963 (9.7%) of those surveyed, ranging from 1.4% in the youngest to 17.3% in the oldest age group. Two thousand four hundred and forty-four (24.5%) of those surveyed had suffered some degree of ankle injury.

Short form 36 questionnaire

The questionnaire containing 36 questions explores eight health dimensions. Normal values of the population examined were defined. Values are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Normal values of the short form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire

| Physical functioning | Physical role | Bodily pain | General health | Vitality | Social functioning | Emotional role | Mental health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 9,630 | 9,929 | 9,518 | 9,941 | 9,817 | 9,894 | 9,940 | 9,674 |

| Mean | 80.80 | 63.45 | 72.15 | 59.95 | 58.86 | 88.46 | 77.62 | 70.14 |

| 25th Percentile | 70.00 | 0.00 | 31.00 | 40.00 | 40.00 | 87.50 | 66.66 | 56.00 |

| 50th Percentile | 95/00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 65.00 | 60.00 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 76.00 |

| 75th Percentile | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 82.00 | 80.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 88.88 |

| Standard deviation | 28.09 | 44.41 | 34.29 | 27.79 | 24.42 | 20.96 | 39.34 | 22.48 |

| Range | 0–100 | 0–100 | 12–100 | 0–100 | 0–100 | 0–100 | 0–100 | 0–100 |

| % Ceiling | 47.1 | 54.8 | 56.3 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 67.5 | 73.3 | 7.5 |

| %Floor | 2.5 | 28.4 | 11.4 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 18.2 | 0.4 |

Discussion

Knowledge of the prevalence of joint complaints is important for several reasons. The economic burden of degenerative conditions outweighs by far other medical conditions, and is one of the leading health care problems worldwide. Exploring the exposed patients; those who already have complaints, but normally would not visit a physician, helps to predict insurance costs, and identifies future candidates for arthroplasty. One of the most thorough screening programs was performed in Iceland, where 1,530 patients were involved. Apart from radiological investigation, genome screening was performed in search of possible genes involved in the inheritance of hip osteoarthritis in a representative sample, [8]. It is one of the few papers in which the age- and sex-standardized prevalence of hip osteoarthritis is defined. They found a 10.8% (12% for men, 10% for women) overall prevalence of hip osteoarthritis in the population examined, rising from 2% at 35–39 years old to 35.4% for the 85 years and older age group. The limitations of this unique survey included the screening of only those who undergoing colon radiography, and the inclusion of only people above 35 years. Several factors influence and play a role in the development of symptomatic or asymptomatic degenerative diseases, including genetics, age, gender, race, etc. After a certain age radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis can be detected in the majority of people [4, 6]. The question is whether or not it causes pain and disablement. On the other hand, pain does not necessarily define degenerative diseases.

Since the criteria used for epidemiological studies of osteoarthritis vary, a discrepancy in the prevalence outcomes is inevitable; however, the diagnosis is more or less based on the radiographic changes of the joint and characteristic subjective symptoms. In the case of the hip, the radiological assessment methods used the most are the Kellgren and Lawrence system [10], the Croft [5] classification, and the measurement of the minimum joint space width. In a recent study Jacobsen et al. found that self-reported hip pain showed the closest association to minimum joint space width equal or inferior to 2 mm, regardless of other radiological features of osteoarthritis [9]. With their method, the prevalence of hip OA ranged from 4.4% to 5.3% in participants over 60 years of age. In another study, a population sample of 1,071, aged over 45, was split into a hip pain negative and a hip pain positive group, and radiographic analysis was performed. Hip pain prevalence was found to be 7% in men and 10% in women. Sixteen percent of those with pain had severe OA and only 3% of those who were hip pain-negative had severe OA [3]. Age-related hip pain prevalence ranged from 2.9% in the youngest group to 38.5% in the oldest group in our survey. Thus, the prevalence of hip pain was approximately three times higher than in the comparable age groups of other surveys. This difference may arise from several factors, including the lack of an agreed definition of hip pain. Many of those surveyed, despite the accuracy of our questionnaire, misinterpreted low back pain in trying to localize hip pain, thus, there is probably a higher prevalence in fact.

The probability of misinterpretation in the case of knee symptoms is lower than in other joints. Dawson et al., in a screening program for knee and hip pain in an age group of 65 and older, found a prevalence of 32.6% with knee pain [7]. Our overall finding of 30.3% with knee pain is comparable with these and other data [4, 12]; however, the true prevalence of knee osteoarthritis is expected to be closer to 10.8%, the number of those who suffered from regular, daily knee pain. The 658 (6.6%) people who had undergone knee aspiration, the 956 (9.6%) who had received knee injections, and the 641 (6.4%) who had undergone operations for knee problems are certainly at higher risk of knee osteoarthritis as well as those who, without radiological evidence, presumably have a varus (1,831; 18.5%), or valgus (1,962; 19.9%) deformity.

Unlike the hip and knee joints, the ankle is rarely affected by primary osteoarthritis. Although the most common cause of this disease is trauma, the true prevalence is difficult to determine. An estimated prevalence can be given if we consider that in clinical practice eight to nine times as many patients are seen with knee problems than with ankle problems, and it is estimated that the number of total knee replacements performed is 24 times higher than the number of cases of ankle arthrodesis and arthroplasty combined [14]. Compared with this, our result of frequent ankle pain in 9.7% of those surveyed seems to be exaggerated, and may only reflect temporary discomfort after injury or the pain of instability.

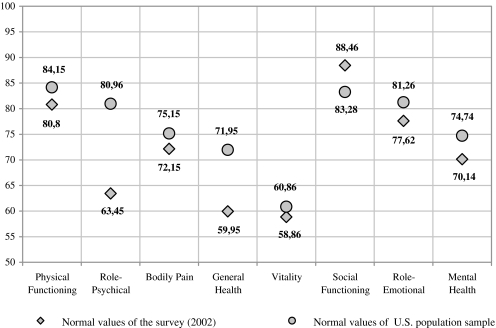

By exporing the eight health dimensions of the SF-36 questionnaire, and comparing our results with international data (Fig. 1), we found that except for social function, all values were inferior to those in the American sample. We also found that the general health status of the population examined worsened progressively with age. This, in our opinion, may explain the discrepancies between the prevalence of degenerative joint complaints; however, radiographic analysis is required to provide exact data on this issue.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the normal values of the SF-36 questionnaire with US values

References

- 1.Badley EM, Tennant A (1993) Impact of disablement due to rheumatic disorder in a British population: estimates of severity and prevalence from the Calderdale rheumatic disablement survey. Ann Rheum Dis 52:6–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Birrell F, Johnell O, Silman A (1999) Projecting the need for hip replacement surgery over the next three decades: influence of changing demography and threshold for surgery. Ann Rheum Dis 58:569–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Birrell F, Lunt M, Macfarlane G, Silman A (2005) Association between pain in the hip region and radiographic changes of osteoarthritis: results from a population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 44:337–341 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Brown CR Jr (2003) Arthritis: overview. In: Callaghan JJ, Rosenberg AG, Rubash HE et al. (eds) The adult knee. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 465–468

- 5.Croft P, Cooper C, Wickham C, Coggon D (1990) Defining osteoarthritis of the hip for epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol 132:514–522 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.D’Ambrosia RD (2005) Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Orthopedics 28:201–205 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Dawson J, Linsell L, Zondervan K et al (2004) Epidemiology of hip and knee pain and its impact on overall health status in older adults. Rheumatology (Oxford) 43:497–504 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ingvarsson T (2000) Prevalence and inheritance of hip osteoarthritis in Iceland. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 298:1–46 [PubMed]

- 9.Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Soballe K, Gebuhr P, Lund B (2004) Radiographic case definitions and prevalence of osteoarthritis of the hip: a survey of 4,151 subjects in the osteoarthritis substudy of the Copenhagen City heart study. Acta Orthop Scand 75:713–720 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS (1957) Radiological assessment of osteoarthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 16:494–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Koppenheffer M, Rose KM (2003) Joints still volume mainstay, but margin pressures increasing. In: Cheng A (ed) Executive summary: future of orthopedics: strategic forecast for a service line under siege. Health Care Advisory Board, Washington DC, pp 26–29

- 12.Petterson I, Jacobson L, Silman L et al (1996) The epidemiology of osteoarthritis of peripheral joints. Ann Rheum Dis 55:651–694

- 13.The Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 for prevention and treatment of musculoskeletal disorders, Lund, Sweden, April 17–18, 1998. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 281:1–86 [PubMed]

- 14.Thomas RH, Daniels TR (2003) Ankle arthritis. Current concept review. J Bone Joint Surg 85-A:923–936 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ware JE (1993) SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Health Institute, New England Medical Center Hospitals, Boston