Abstract

We report our results after ten year follow-up of 107 consecutive ABG-I hip prostheses implanted between June 1990 and December 1992: Only 84 prostheses were still in the study after ten years, but only six patients had undergone surgical revision. We can consider our clinical outcomes as excellent, with a whole-implant survival rate greater than 96%, a mean Merle D’Aubigne and Postel score increasing from 7.97 before operation to 16.17 at ten year follow-up, and a personal subjective assessment as excellent or good in 82.14% of patients. However, radiographic outcomes are more worrying: around 90% of patients show a stress-shielding phenomenon and granulomatous lesions in the proximal femur, and more than 82% suffer polyethylene wear greater than one millimetre (mean 1.68 mm). We think that zirconia stem heads and hooded antiluxation PE inserts are determining factors in the process of PE wear and, secondarily, in cancellous bone resorption and bone osteolysis.

Résumé

Nous rapportons les résultats, après dix ans de suivi, de 107 prothèses de hanche de type ABG-1, implantées entre juin 1990 et décembre 1992. Seulement 84 patients étaient toujours suivis, mais seulement 6 avaient eu une reprise chirurgicale. Nous considérons les résultats cliniques comme excellents avec une survie des implants de plus de 96%, un score de Merle d’Aubigné augmenté de 7,97 à 16,17 à dix ans et une appréciation subjective des patients bonne ou excellente dans 82,14% des cas. Cependant l’évolution radiologique est préoccupante : prés de 90% des patients montrent des phénomènes de stress shielding et des lésions granulomateuses du fémur proximal, et plus de 82% ont une usure du PE de plus de 1 mm (moyenne : 1,68). Nous pensons que la tête en Zircone et le rebord anti-luxation des inserts en PE sont déterminants dans l’usure et secondairement dans l’ostéolyse.

Introduction

The great expansion of prosthetic hip surgery in the 1970s and the 1980s was shadowed by osteolysis secondary to cement degradation and polyethylene (PE) wear.

The first cementless designs failed earlier than cemented ones; strain transmission across the sharp edges of the acetabular cup brought about early failure; straight stems developed a progressive phenomenon of stress-shielding. Both problems were impaired by osteolysis due to PE particles.

New designs, alloys and surface coatings have been developed since the end of the 1980s. Shorter and proximally wider femoral stems, some of them anatomically designed with or without porous coating, hemispherical acetabular implants and new friction couples are continuously improving clinical outcomes. However, the radiographic results are not evolving as favourably as the clinical results. Femoral stress shielding does not disappear, and periprosthetic osteolysis is more intense than in cemented designs.

Materials and methods

We present a prospective study of a cementless anatomical hydroxyapatite (HA)-coated hip prosthesis, the ABG system (Howmedica Europe, Staines, UK). Metallic implants are made of Ti6Al4V. The HA-coated (60μ) proximal third of the femoral stem has a macro-relief scaled surface; the distal part has a grit-blasted surface and tapers slightly; proximal rotational stability is helped by means of the metaphysis filling and a global 12° anteversion in the coronal plane (7° in the metaphyseal portion and 5° in the neck). The exact-fit hemispheric acetabular cup is totally HA coated and has 12 holes for spikes or screws. All the femoral stem heads but three (Francoball) were made of zirconia, and all but one (22 mm) were 28 mm in diameter.

We studied the survivor implants after ten years’ follow-up. All patients consented to participate in the study. We evaluated them preoperatively (demography, diagnosis, functional score) and postoperatively at three and six months and then annually until the ten year follow-up. Clinically we applied the Merle D’Aubigne (MDA) score [17], and also recorded the patients’ subjective assessment of the outcome as excellent, good, fair, poor or bad. Radiographically we evaluated the bone response to implants and the possible osteolysis secondary to PE wear. We measured:

The preoperative anatomy of both the hips.

The size and position of the acetabular cup, according to the distance between the anatomical and the prosthetic rotation centre: correct if <3 mm; high, low, medial or lateral if >3 mm. We also recorded the position of the inner antiluxation hood.

The size and position of the femoral stem was considered: adequate (distance between the limit of the femoral stem and the inner side of the cortices at the metaphysis is 3 mm), small (>3 mm), and large (<3 mm).

The bone response to implants at De Lee–Charnley [5] and Grüen and McNeice [8] zones: cancellous bone densification and resorption, cortical thickening or thinning, reactive lines (thin radiodense lines parallel to and separated by less than 2 mm from the implant), and radiolucent images (>2 mm and without relationship to any radiopaque area) around implants, cyst (scalloped image >2 mm diameter at the prosthesis interface), and pedestal images around the distal tip of the femoral stem.

PE wear was analysed according to Livermore et al. [12]; its direction from the centre of the acetabular cup was (+) if medial and (−) if lateral.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Chi-square method for categorical data and comparison of percentages; Student’s t test was used for the comparison of means for isolated or between pairs related data as appropriate, with Pearson correlation. The level of significance was set atp<0.05.

Results

Epidemiology

Between June 1990 and December 1992, we implanted 107 prostheses into 95 patients: 53 males (55.41%) and 42 females (44.59%), with mean ages of 57.73 and 62.71 years respectively. Side distribution was: 50.47% right and 49.53% left (12 bilateral). The processes responsible for joint destruction were: 74 osteoarthritis (77.57%), 14 avascular necrosis (14.95%), and seven rheumatoid arthritis (7.48%).

Surgical technique

The postero-lateral approach was used in all patients but one. All the PE inserts were either posteriorly or postero-superiorly hooded.

At 10-year follow-up 84 hip prostheses remained in the study: 14 patients (14.73%) had died (three bilaterally implanted), and six prostheses (5.61%) were surgically revised, although only four for loosening (four acetabular cups and one femoral stem).

Clinical outcomes

The mean MDA score increased from 7.97 before operation to 16.17 at ten year follow-up; 36 patients (42.86%) had a score of 18; 63 (75%) had no pain, 57 (67.86%) maintained total mobility, and 42 (50%) were able to walk unrestrictedly despite their advanced mean age and comorbidity; 21 (25%) had some minor pain. The average mobility was: flexion 95.8°, extension 0°, abduction 31.5°, adduction 12.8°, external rotation 26.3°, and internal rotation 8.7°. Fifty patients (59.52%) showed leg asymmetry [<1 cm in 40 (47.62%) and >1 cm in ten (11.90%)]. The subjective global results were excellent in 46 patients (54.76%), good in 23 (27.38%), fair in seven (8.33%), poor in five (5.95%) and bad in three (3.57%); more than 82% of patients retain almost normal joint function after ten years follow-up.

Radiographic outcomes

We report only those findings relevant for the objective of this paper.

Implant size and position

Implant size and position are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Size and position of the acetabular cups and femoral stems

| Parameter | Initial group | Ten-year follow-up group |

|---|---|---|

| Acetabular cup size | ||

| 46 mm ∅ | 1 (0.93%) | 1 (1.19%) |

| 48 mm ∅ | 8 (7.48%) | 6 (7.14%) |

| 50 mm ∅ | 13 (12.15%) | 11 (13.10%) |

| 52 mm ∅ | 14 (13.08%) | 12 (14.29%) |

| 54 mm ∅ | 15 (14.02%) | 15 (17.86%) |

| 56 mm ∅ | 28 (26.17%) | 24 (28.57%) |

| 58 mm ∅ | 16 (14.95%) | 7 (8.33%) |

| 60 mm ∅ | 11 (10.28%) | 7 (8.33%) |

| 62 mm ∅ | 1 (0.93%) | 1 (1.19%) |

| Position | ||

| Correct | – | 26 (30.95%) |

| High | – | 23 (27.38%) |

| Low | – | 9 (10.71%) |

| Medial | – | 9 (10.71%) |

| Lateral | – | 17 (20.24%) |

| Femoral stem type | ||

| No. 2 | 5 (4.67%) | – |

| No. 3 | 19 (17.76%) | – |

| No. 4 | 38 (35.51%) | – |

| No. 5 | 33 (30.84%) | – |

| No. 6 | 10 (9.35%) | – |

| No. 7 | 2 (1.87%) | |

| Length of femoral stem head neck | ||

| −5 mm | – | 1 (0.93%) |

| −3 mm | – | 60 (56.07%) |

| 0 | – | 38 (35.51%) |

| +3 mm | – | 5 (4.67%) |

| +5 mm | – | 3 (2.80%) |

| Size | ||

| Adequate | – | 31 (36.9%) |

| Large | – | 27 (32.1%) |

| Small | – | 26 (31.0%) |

| Position | ||

| Neutral | – | 36 (42.86%) |

| Valgus <5° | – | 22 (26.19%) |

| Varus <5° | – | 26 (30.95%) |

Thirty-nine patients (46.4%) showed contact between the femoral stem and proximal cortices immediately after the operation: 21 (25%) with the medial cortex, and 18 (21.4%) with the lateral cortex. Stem alignment in the femoral canal was almost constant throughout the study; none of them had more than 4° valgus and only one more than 5° varus at ten year follow-up. In the lateral view, 63 patients (75%) had the stem in neutral position, 17 (20.2%) showed distal contact with the posterior cortices, and four (4.8%) with the anterior.

The mean height of the top of the stem from the tip of the great trochanter was 1.27 mm (range −12.33 to 13.15; SD 5.16) immediately after operation, 2.99 mm (−12.33 to 11.92; SD 5.43) at the one year follow-up, and 4.72 mm (−9.86 to 13.97; SD 5.38) at the ten year follow-up; this involves a progressive femoral stem subsidence that was 2.05 mm (−0.82 to 6.57; SD 1.87) and 3.76 mm (0–10.68; SD 2.43) at one year and ten year follow-up. Cross-correlation analysis demonstrated a relation, albeit not quite significant, between femoral stem size and subsidence: the small size showed less subsidence (1.53 mm and 3.02 mm at one and ten year follow-up; difference 1.49 mm) than the adequate size (2.31 mm, 4.04 mm; difference 1.73 mm), and the large size (2.28 mm, 4.15 mm; difference 1.87 mm).

Polyethylene wear displayed a mean value of 0.69 mm (0–2.05; SD 0.45) and 1.68 mm (0.31–4.50; SD 0.86) at five and ten year follow-up; the mean values of volumetric wear were 348.63 mm3 (0–1038.56; SD 228.68) and 849.66 mm3 (158.06–2278.6; SD 434.59). Cross-correlation analysis showed a significant relation between more intense PE wear and low position of the acetabular cup (p=0.038) only at the one year follow-up. We also observed intense PE wear in acetabular cups with opening angle >46°, and in patients younger than 65 (<55 years old: −0.5918 and −0.8340 mm; 55–65: −0.5325 and −1.3107 mm; >65:−0.475 0and −1.1504 mm) at both the one year and the ten year follow-up, but the differences were not significant.

Bone response to the implants

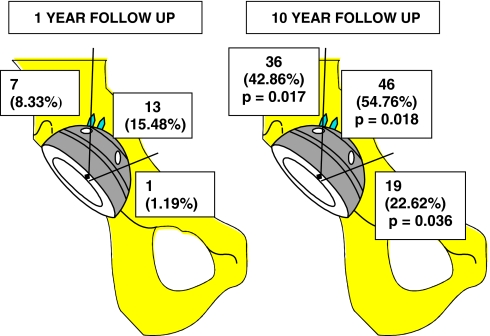

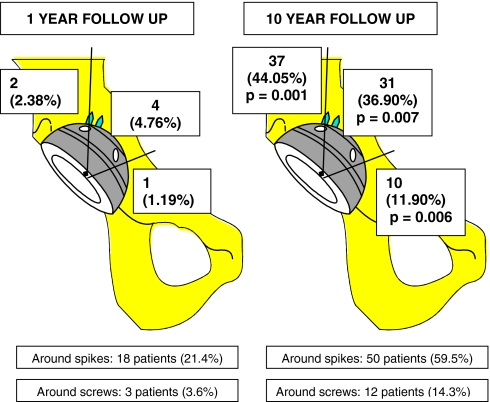

Progression of cancellous bone growth and resorption around the acetabular cup are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. We found neither reactive nor radiolucent lines. However, we observed growing granulomatous lesions (Fig. 3). Cross-correlation analysis showed low incidence of cystic lesions in zone 1 of the acetabulum in patients older than 65 years at the time of implantation, both at one year (p=0.315) and at ten years (p=0.034). Some non-significant relations showed very interesting tendencies: the incidence of cystic lesions in zone 1 was higher than expected, both at the one year and the ten year follow-up, in patients with the acetabular cup in a low position.

Fig. 1.

Cancellous bone growth around acetabular cup at 1- and 10-year follow-up

Fig. 2.

Bone resorption around the acetabular cup at 1- and 10-year follow-up

Fig. 3.

Granulomatous lesions around the acetabular cup at 1- and 10-year follow-up

The evolution of cancellous bone growth and resorption around the femoral stem from the first to the tenth year follow-up are shown in Figs. 4 and 5. Progression of reactive lines and pedestal images around the femoral stem at the one year and the ten year follow-ups are shown in Table 2. We did not find radiolucent lines around the femoral stem. However, we observed granulomatous lesions around its proximal areas (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

a Cancellous bone growth at 1- and 10-year follow-up: AP view. b Cancellous bone growth at 1- and 10-year follow-up: lateral view

Fig. 5.

a Bone resorption around the femoral stem: AP view. b Bone resorption around the femoral stem: lateral view

Table 2.

Number of patients with reactive lines and pedestal images around the femoral stem (AP view)

| Grüen zone | Reactive lines / Pedestal | p values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At 1 year follow-up | At 10 year follow-up | ||

| 3 | 24 (28.57%) / 16 (19.05%) | 9 (10.71%) / 9 (10.71%) | 0.002 – 0.521 |

| 4 | 31 (36.90%) / 6 (7.14%) | 9 (10.71%) / 9 (10.71%) | 0.001 – 0.625 |

| 5 | 36 (42.86%) / 7 (8.33%) | 8 (9.52%) / 8 (9.52%) | 0.007 – 0.370 |

| 6 | 3 (3.57%) / 0 | 1 (1.19%) / 0 | 0.846 |

| 7a | 0 / 0 | 0 / 0 | |

| 7b | 1 (1.19%) / 0 | 0 / 0 | |

Table 3.

Number of patients with femoral granulomatous lesions >2 mm in diameter

| Grûen zone | At 1-year follow-up | At 10-year follow-up | p values |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 25 (29.76%) | 66 (78.57%) | 0.011 |

| 1b | 1 (1.19%) | 40 (47.62%) | 0.001 |

| 1c | 0 | 37 (44.05%) | 0.001 |

| 2 | 0 | 4 (4.76%) | 0.064 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 2 (2.38%) | 0.157 |

| 7a | 40 (47.62%) | 77 (91.66%) | 0.001 |

| 7b | 3 (3.57%) | 28 (33.33%) | 0.001 |

| 1 lat. | 34 (40.50%) | 74 (88.10%) | |

| 2 lat. | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | |

| 6 lat. | 0 | 9 (10.7%) | |

| 7 lat. | 32 (38.10%) | 80 (95.2%) |

Cross-correlation analysis showed only few significant findings. Patients with large femoral stems had a lower incidence of bone growth in zone 6 at ten year follow-up than patients with normal stems. We did not find any significant correlation with the presence of cystic lesions around the femoral stem, although it was higher than expected in zone 1a at the ten year follow-up in patients younger than 55 at the time of implantation.

Discussion

Given the survival rate of our implants we agree with other authors [4] who consider the stem fixation more reliable than that obtained for the acetabular cup.

Clinical outcomes were very satisfactory: 82% of our patients considered their functional situation excellent or good at ten year follow-up.

Radiographically, as with other authors using this implant [9] we did not observe acetabular cup migration. We think that porous coating improves the interlocking by acetabular bone [4] and that HA coating accelerates bone growth through the micro-porous surface and improves contact [22] between host bone and implant, avoiding migration. Surprisingly we found a progressive subsidence of the prosthetic stem into the femoral canal, frequent with non-anatomical tapered stems but unexpected in an anatomical HA-coated implant. We found no statistically significant correlation to explain this phenomenon, but undersized stems subsided less than adequate and oversized ones.

On the other hand, we detected PE wear in many more patients than expected. The mean wear amounts to 0.168 mm per year, similar to that reported by Charnley (0.10–0.19 per year) [3] and similar to or less than others with cementless systems [10, 23].

In contrast to other authors [10] we found no significant correlation between PE wear and patients’ gender or age, although it was clearly more intense in young men. However, it may be influenced by excessive vertical load transmission. We also detected more intense PE wear in patients fitted with zirconia heads. Frictional heating of PE cups articulated with zirconia heads has been previously reported as responsible for accelerated PE wear [13]. In any case, two issues may be decisive in the origin and evolution of this problem: (1) all our patients were implanted with a hooded PE insert that facilitates the repetitive contact between the stem neck and the prominent PE; (2) this contact can be responsible for a dragging movement of the femoral head over the interior surface of the insert [9]. Both of these factors accelerate PE wear.

Despite the anatomical design of the stem and the HA coating of the implants, the bone response to them was unexpected and disappointing: femoral stress shielding was present in around 90% of patients (Fig. 1), a higher incidence than that obtained with femoral stems fixed either proximally [19] or distally [1, 16] or even with HA-coated implants [4]. In contrast to the findings of Engh et al. [6] with AML implants, progressive proximal bone resorption did not stop after the two year follow-up but increased continuously (Fig. 2), as observed with other non-anatomical [1, 7, 18] and anatomical [11] devices, and even more than that reported by the multicentre International ABG Study Group [9, 25]. Proximal bone resorption was systematically associated with a parallel process of distal cancellous bone growth (Fig. 1) and cortical thickening that affected progressively more distal zones (zones 2–6 at one year, zones 3–5 at ten years). We found no significant correlation between bone resorption and either the presence of granulomatous lesions around the implants or more intense rates of PE wear. The percentage of reactive lines around the tip of the stem decreased from 43% at one year follow-up to 11% at ten years; this is also attributable to the progressive femoral stress shielding process, although femoral stem subsidence, not recorded by the International ABG Study Group [9, 25], could also be implicated. The statistical analysis of possible causes of stress shielding showed a lower incidence of cancellous bone growth in medial and proximal femoral zones in patients fitted with oversized femoral stems than in those with adequate or undersized stems. We interpret this as a consequence of excess distal load transmission by oversized stems, which is less effectively counteracted if there is less cancellous bone between the stem and the cortical bone in proximal areas [24]. On the other hand, in the AP view we observed a lower incidence of bone resorption at the ten year follow-up in medial overloaded zones (femoral stem in varus) than in underloaded stems. In these cases overload transmission probably protects against the deleterious effect of some factors such as preoperative low bone density [19], decreased proximal blood supply during surgery [2, 21], and the funnel shape of the proximal femur of some patients [9].

Bone response to the implant in the acetabulum was better. We found progressive bone resorption in the three zones of De Lee and Charnley [5]. Cancellous bone growth was less frequent and clearly decreasing in zone 1, while it remained more or less similar in zones 2 and 3.

We agree with the hypothesis that migration of PE wear particles is responsible for decreasing bone density [9, 15] and progressive osteolysis [14] through bone resorption in the acetabulum and femur [9, 20]. The incidence of granulomatous osteolytic lesions was exceptionally high among our patients, in both proximal femur and acetabulum, and clearly increasing with time after operation; we found scores equal to or greater than those recorded by other authors for various femoral stems [4], including the International ABG Study Group [9]. In the acetabulum we found a growing and worrying incidence of osteolytic lesions in all zones. These lesions are granulomas containing PE wear particles [2] whose progression is favoured by acetabular cup holes, presence of spikes and screws, increased synovial fluid pressure and gravity. In any case we agree with the International ABG Study Group [9] that a problem of sensitivity to PE must be implied in the generation of these osteolytic lesions, because not all patients develop lesions of equal dimensions with similar amounts of PE wear.

Although the radiographic images of the bone around the acetabular cup gave slightly less cause for concern, preventive surgical revision of asymptomatic patients demonstrated enormous osteolytic lesions around almost the entire extension of the cup, which were held stable by only a few “flying buttresses” of bone.

We believe that this anatomical HA-coated implant should be evaluated independently from the problems caused by PE wear, which is increased and accelerated by zirconia heads. It probably would explain the difference between our radiographic outcomes and those found by other researchers who did not use zirconia heads [20].

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude to Dr. L. García-Dihinx Checa, who introduced the ABG system in our institution and started the multicentre International ABG Study14 years ago; he is responsible for a great number of these implants and follows up many ABG patients yearly. We are also grateful to Dr. A. Sola Cordón, who contributed to the location and radiographic assessment of several patients. Finally, we wish to acknowledge all the staff members and residents of our department for their daily collaboration in the treatment of these patients.

References

- 1.Brodner W, Bitzan P, Lomoschitz F, Krepler P, Jankovsky R, Lehr S, Kainberger F, Gottsauner-Wolf F (2004) Changes in bone mineral density in the proximal femur after cementless total hip arthroplasty. A five-year longitudinal study. J Bone Joint Surg 86B: 20–26 [PubMed]

- 2.Capello WN, D’Antonio JA, Manley MT, Feinberg JR (1998) Hydroxyapatite in total hip arthroplasty: clinical results and critical issues. Clin Orthop 355:200–211 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Charnley J (1966) Total prosthetic replacement for advanced coxarthrosis. Comptes Rendus de la Reunion de la S.I.C.O.T. (10th International Congress) Paris, France, 311

- 4.D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Manley MT, Feinberg J (1997) Hydroxyapatite coated implants: total hip arthroplasty in the young patient and patients with avascular necrosis. Clin Orthop 344:124–138 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.DeLee JG, Charnley J (1976) Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop 121:20–32 [PubMed]

- 6.Engh CA, McGovern TF, Schmidt LM (1993) Roentgenographic densitometry of bone adjacent to a femoral prosthesis. Clin Orthop 292:177–190 [PubMed]

- 7.Engh CA, Culpepper W (1993) Femoral fixation in primary total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics 20:771–773 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Grüen TA, McNeice GM, Amstutz HC (1979) “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop 141:17–27 [PubMed]

- 9.Herrera A, Canales V, Anderson J, García-Araujo C, Murcia-Mazón A, Tonino AJ (2004) Seven to 1 0years followup of an anatomic hip prosthesis. An international study. Clin Orthop 423:129–137 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kawamura H, Bourne RB, Dunbar MJ, Rorabeck CH (2001) Polyethylene wear of the porous-coated anatomic total hip arthroplasty with an average 11-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty 16 (8 Suppl 1):116–121 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kiratli BJ, Heiner JP, McBeath AA, Wilson MA (1992) Determination of bone density by dual x-ray absorptiometry in patients with uncemented total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Res 10:836–844 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Livermore J, Ilstrup D, Morrey B (1990) Effect of femoral head size on wear of the polyethylene acetabular component. J Bone Joint Surg 72A:518–528 [PubMed]

- 13.Lu Z, McKellop H (1997) Frictional heating of bearing materials tested in a hip joint wear simulator. Proc Inst Mech Eng (H), 211:101–108 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Maloney WJ, Woolson ST (1996) Increasing incidence of femoral osteolysis in association with uncemented Harris-Galante total hip arthroplasty: A follow-up report. J Arthrosplasty 11:130–134 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Maloney WJ, Galante JD, Anderson M, Goldberg V, Harris WH, Jacobs J, Kraay M, Lachiewicz P, Rubash HE, Schutzer S, Woolson ST (1999) Fixation, polyethylene wear, and pelvic osteolysis in primary total hip replacement. Clin Orthop 369:157–164 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.McAuley JP, Culpepper WJ, Engh CA (1998) Total hip arthroplasty: concerns with extensively porous coated femoral components. Clin Orthop 355:182–188 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Merle D’Aubigne R, Postel M (1954) Functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg 36A:451–475 [PubMed]

- 18.Mulroy WF, Estok DM, Harrys WH (1995) Total hip arthroplasty with use of so-called second-generation cementing techniques: a fifteen-year-average follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg 77A:1845–1852 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Nourbash P, Paprosky W (1998) Cementless femoral designs concerns. Rationales for extensive porous coating. Clin Orthop 355:189–199 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Nourissat Ch, Adrey J, Berteaux D, Gueret A, Goalard Ch, Hamon G (1999) ABG Scientific Group: ABG cementfree hip replacement with hydroxyapatite: clinical results at 10 years. SICOT Meeting, Sydney

- 21.Panisello Sebastiá JJ, Martínez Martín A, Herrera Rodríguez A, Cuenca Espiérrez J, Peguero Bona A, Canales Cortés V (2001) Cambios remodelativos periprotésicos a 7 años con el vástago A.B.G.-I. Rev Ortop Traumatol 45:216–221

- 22.Rahmy A, Tonino A, Djin Tan W (1994) Quantitative analysis of Technetium-99-m-methylene diphosphonate uptake in unilateral hydroxyapatite-coated total hip prostheses: first year of follow-up. J Nuclear Med 35:1788–1791 [PubMed]

- 23.Rogers A, Kulkarni R, Downes EM (2003) The ABG hydroxyapatite-coated hip prosthesis. One hundred consecutive operations with average 6-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty 18 (5):619–625 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Stephenson P, Freeman M, Revell P, Germain J, Tuke M, Pirie C (1991) The effect of hydroxyapatite coating on ingrowth of bone into cavities in an implant. J Arthroplasty 6:51–58 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Tonino AJ, Rahmy A (2000) The International ABG Study Group: 5- to 7-year results from an international multicentre study. J Arthroplasty 15:274–282 [DOI] [PubMed]