Abstract

Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty using a short skin incision is a subject of much debate in the literature. The present study estimates the possible minimal length of the exposure in an unselected patient cohort and compares the lateral mini-incision technique and traditional total hip arthroplasty (THA). One hundred and two patients were divided into three groups according to the type of surgery and length of incision: mini-incision (less than 10 cm) was performed in 38 patients; midi-incision (10–14 cm) in 43; and standard-incision (longer than 14 cm) in 21 patients. No statistical difference was found with regard to intraoperative and total blood loss, the rate of complications, and postoperative recovery. Significantly decreased body mass index (BMI), shorter operative time, and higher number of hips with malpositioning of the acetabular cup were found in the mini-incision group. These patients, however, experienced less pain in the early postoperative period and were highly satisfied with the cosmetic results. The length of incision was shortened and optimized (less than 14 cm) in 82% of patients, and mini-incision was performed in 38 patients of this unselected cohort. Because of the understandable demand of the patients for less invasive intervention, the surgeon should use a smaller but not necessarily mini-incision with minimal soft tissue trauma that still allows him to perform the procedure well, without compromising the type of implants and the otherwise excellent long-term results. Randomized prospective studies are needed to explore the real value of the minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty.

Résumé

La chirurgie arthroplastie de la hanche par voie mini invasive est un sujet de débat et de controverse dans la littérature. Cette étude a pour but d’estimer la longueur minimale de la voie d’abord sur une suite de patients non sélectionnés et de comparer la technique de mini incision avec la technique d’incision traditionnelle antérolatérale. Cent deux patients ont été divisés en trois groupes, en fonction du type de chirurgie et en fonction de la longueur d’incision. Premier groupe: mini incision moins de 10 cm chez 38 patients, deuxième groupe: incision moyenne 10 à 14 cm chez 43 patients et troisième groupe: incision standard, supérieure à 14 cm chez 21 patients. Aucune différence statistique n’a été trouvée pour la perte sanguine et sur le taux des complications post-opératoires. Dans le groupe des mini incisions peu de sujets avaient une surcharge pondérale, par contre, il existait un grand nombre de hanches avec une mal position de la cupule. Ces patients ont cependant présenté moins de douleur dans la période post-opératoire et ont été très satisfaits du résultat cosmétique. La longueur de l’incision dans la chirurgie prothétique de la hanche peut être raccourcie et la longueur optimum peut être de moins de 14 cm chez 82% des patients. Une mini incision a été réalisé dans cette série, chez 38 patients du fait de la demande des patients pour une chirurgie mini invasive, les chirurgiens ont utilisé une petite incision avec un minimum de traumatisme des tissus mous. Cette mini incision doit donc permettre au chirurgien de réaliser son intervention correctement sans compromission sur le type d’ implants, ni sur la qualité des résultats à long terme. Il n’y a pas besoin pour cela nécessairement d’une mini incision néanmoins des études prospectives randomisées doivent être réalisées pour explorer le vrai résultat de la chirurgie arthroplastie par voie mini invasive.

Introduction

Minimally invasive surgical (MIS) techniques, like laparoscopic gall-bladder surgery, hernia surgery, prostatectomy, arthroscope-guided surgery of the joints or plating of fractures, have gained enormous popularity over the past decades. Recently, the concept of minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty (THA) has been introduced by some authors [1, 2, 10, 11, 15] and the media picked up and promoted it without having enough evidence-based facts about the results [12, 14]. The advocates of minimally invasive THA use modified posterolateral [2, 7, 15, 18], ventral [19], anterolateral [10] or lateral [3, 9] one-incision techniques or the two-incision approach described by Berger [1]. These techniques would have to be less invasive to the muscles or bone, and result in shorter recovery time, less pain and blood loss, shorter hospitalization time, fewer complications and better cosmetic results.

The first results of minimally invasive THA have, however, created much controversy among orthopedic surgeons: some of the authors presented the clear advantages of this procedure [1, 4, 5, 9, 10, 17, 19], comparing them with those of the standard incision, while others reported similar results or greater complications [6, 7, 20].

The aim of this prospective study was to estimate the possible minimal length of the exposure in an unselected patient cohort and to compare the results of THA performed with mini-incision vs. standard incision.

Patients and methods

The study group comprised a consecutive series of 102 patients who underwent primary unilateral total hip replacement between the beginning of 2003 and the end of 2004. With the exception of the severe forms of congenital dislocations of the hip (CDH) and revision THA, none of the patients was excluded. The indications for surgery were: primary osteoarthritis in 76 patients, secondary osteoarthritis in 17, aseptic necrosis of the femoral head in six, and post-traumatic arthritis in three patients. All arthroplasties were performed by the senior author (MS) and all examinations and evaluation of the data were carried out by independent observers. The implants were cemented in 60 cases and cementless in 42 cases. The capsule of the hip joint was excised in 73 cases and retained in 29 cases. A direct lateral approach was used. Patients were neither randomly selected prior to the operation for the type of surgery nor informed about the length of the incision in the immediate postoperative period. The wounds were covered with dressings of uniform length at the end of the operation. The THA was always started initially with a short skin incision (less than 10 cm) and then extended as necessary during surgery. The length of the incision was measured at the end of the operative procedure. A fluoroscope was not used during the operations. For better visualization of the acetabulum and femoral shaft, bent Hohman retractors and spike retractors were used.

If there were no contraindications, all patients had donated one or two units of autologous blood 1 month before, which was retransfused to the patient on the day of surgery. The postoperative haemoglobin and haematocrit levels were determined after all units had been donated.

According to the length of the incision, three groups were formed: the incision was less than 10 cm in 38 cases (mini-incision group), it was between 10 and 14 cm in 43 cases (midi-incision group), and it was longer than 14 cm in 21 cases (standard-incision group).

The data collected for analysis were patients’ age, height, weight, body mass index (weight in kilograms/height in metres2), type of prosthesis, surgical time, and retention or excision of the joint capsule. Pain was estimated by the individual visual analog scale on the third postoperative day. Complications were recorded both intraoperatively (fracture of the femoral stem, etc.) and postoperatively (deep vein thrombosis, postoperative dislocation of the prosthesis, hematoma, nerve injury, etc.).

Intraoperative blood loss was measured in gauze and in a fluid container with suction drainage. The overall blood loss resulting from operation was calculated by the percentage drop from the preoperative haemoglobin level to the level measured on the first postoperative day, as well as measuring the pre- and postoperative haematocrit values. The amount of the transfused autologous blood, sex, and body weight of the patient were also taken into consideration.

One of the authors (G.S) who did not attend the operations and was blinded to the length of the incision, analyzed the postoperative anteroposterior radiographs of the pelvis. Parameters of the implants like cup inclination (abduction angle, normal range between 35 and 55°) and stem alignment (classified as varus, neutral, and valgus, normal range ±5° to the ventral axis of the femur) were estimated.

Functional outcome was examined by clinical evaluation during the hospital stay and at the 6-week and 3-month postoperative follow-up visits. The early activities of the patients, such as sit-to-stand transfer and bed-to-chair transfer with or without assistance, were evaluated on the first postoperative day. Walking ability and walking distance with or without support were assessed later at ambulatory visits.

Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistica for Windows software (version 4.0, 1993). Unpaired t test was used to compare continuous variables in normally distributed data among the groups. The Pearson chi-squared and Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical data.

Results

Clinical results

A comparison of the data collected in the three groups is presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences among groups with regard to patient age, height, or percentage of cemented or cementless type of endoprosthesis used.

Table 1.

Comparison of the data collected in the three groups. The values are given as the average and the standard deviation, with the range in parentheses

| I. Mini-incision group < 10 cm average: 8.8± 0.98 cm | p* | II. Midi-incision group 10–14 cm average: 12.6± 1.21 cm | p** | III. Standard incision group >14 cm average: 16.1± 1.88 cm | p*** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 38 | 43 | 21 | |||

| Cemented/cementless type of prosthesis | 24/14 | 0.459 | 25/18 | 0.480 | 11/10 | 0.194 |

| Age | 64±12 (41–88) | 0.671 | 62±13 (38–85) | 0.140 | 57±13 (30–80) | 0.071 |

| Weight | 70±13.5 (48–102) | 0.009 | 78±13 (51–104) | 0.986 | 78±19.5 (50–116) | 0.108 |

| Body mass index | 26±3.3 (20–35.2) | 0.026 | 28±4.2 (17.8–37.1) | 0.376 | 29.5±7 (20.3–44.2) | 0.048 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 244±100 (100–550) | 0.399 | 265±114 (70–600) | 0.278 | 304±136 (150–600) | 0.098 |

| Postoperative blood loss | 500±246 (100–1,200) | 0.281 | 443±177 (100–1,050) | 0.608 | 467.5±174 (250–800) | 0.588 |

| Total blood loss | 744±260 (150–1,400) | 0.534 | 708±221 (250–1,300) | 0.286 | 771±235 (400–1,250) | 0.712 |

| Surgical time | 84±16 (50–120) | 0.020 | 93±18 (60–130) | 0.028 | 102±12 (80–120) | <0.001 |

| Decrease in Hgb (%) | 24±11 (6–39) | 0.066 | 20±7 (8–39) | 0.212 | 22.5±8 (11–36) | 0.605 |

| Preoperative pain | 7.8±1.3 (5–10) | 0.703 | 7.9±1.3 (5–10) | 0.128 | 8.5±1.4 (5–10) | 0.073 |

| Postoperative pain | 1.5±1.5 (0–5) | 0.028 | 2.15±1.2 (0–4) | 0.876 | 2.1±1.3 (0–4) | 0.112 |

| Cup inclination | 44.2± 5.3° (30–55°) | 0.348 | 44.8± 3.5° (35–55°) | 0.209 | 44.8±7.2° (30–60°) | 0.686 |

| Percentage of hips within normal range (35–50°) | 89% | 95% | 85% | |||

| Percentage of components that were outliers | 8.25% <35°; 2.75% >50° | 5% >50° | 5% <35°; 10% >50° | |||

| Stem alignment | 92% normal, 8% varus | 0.568 | 95% normal, 5% valgus | 0.969 | 95% normal, 5% varus | 0.682 |

p* = p I–II;

p** = p II–III;

p*** = p I–III

There were, however, significant differences between groups with regard to weight and body mass index (p=0.026 and p=0.048 respectively).

Significantly shorter operation times were measured in the mini-incision group than in the midi- and standard groups (81, 90 and 102 min respectively, p<0.05).

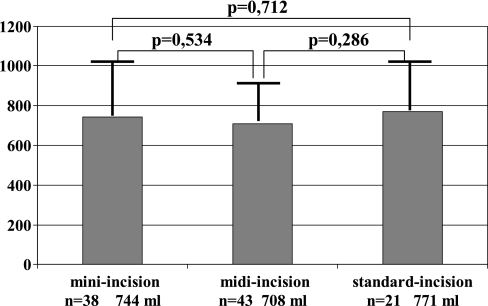

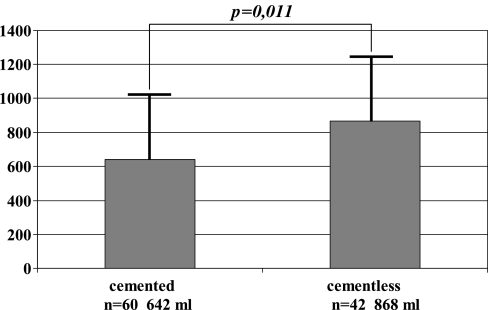

The estimated intraoperative and total blood loss, as well as the drop in the haemoglobin value was slightly increased in the midi-incision and standard incision groups compared with those of the mini-incision group; the differences were, however, not significant (Fig. 1, Table 1). Retention and repair of the joint capsule following the implantation of the endoprosthesis (capsulorrhaphy) neither resulted in decreased blood loss (692 ml following excision of the capsule and 703 ml at capsulorrhaphy, p=0.66) nor influenced the rate of postoperative complications. A significant difference in blood loss was, however, found with respect to the type of the prosthesis (cemented versus cementless: 642 and 868 ml respectively, p=0.011; Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Total blood loss for the mini-, midi-, and standard groups. Statistical analysis revealed differences that were significant

Fig. 2.

Total blood loss for the patients with cemented and cementless endoprosthesis. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference between the two groups

The level of preoperative pain was similar in the three groups (7.76, 7.87, and 8.45 units on the visual analogue scale respectively), the drop in pain from the preoperative to the postoperative level was significantly higher in the mini-incision group (p=0.028).

Both intraoperative and postoperative complications were noted retrospectively. Mechanical and biological complications, such as complete sciatic nerve palsy, intraoperative femoral shaft fracture, loose and unstable components due to the surgical technique, infection or dislocation of the prosthesis in the first 3 postoperative months did not occur in this series of 102 patients. Transient femoral nerve palsy was observed in two patients in the mini-incision group and three in the midi-incision group. Haematoma not requiring reoperation but leading to prolonged drainage was found in four patients in the mini-incision and two in the midi-incision groups. Despite the low molecular weight heparin prophylaxis, the clinical signs of deep vein thrombosis were observed in the three groups in two, three, and two patients respectively. Some of the patients in the mini-incision group had a swelling around the wound in the immediate postoperative period; wound necrosis, however, was not observed.

Radiographic assessment of the position of components

The average inclination (abduction angle) of the acetabular component was similar in all three groups (Table 1): 44.2° in the mini- and 44.8° both in the midi- and standard groups. When, however, the number of cases outside the acceptable normal range (35–55° of abduction), was estimated a greater percentage of outliers was found in the mini-incision and standard incision groups (11% and 15% respectively) than in the midi-incision group (5%). The position of femoral components was within the normal range in 92% of the mini-incision group and in 95% of the other two groups. None of the hips with a cemented endoprosthesis in the groups had a poor cement mantle. Revision surgery was not necessary in any of the patients.

Patient satisfaction was high at the clinical evaluation: over 90% in all groups, with the best results in the mini-incision group where the lesser postoperative pain and better cosmetic results seemed to influence the patients. The mobility and functional outcome in the early postoperative period depended more on the general condition, age, coexistent diseases (diabetes mellitus, deafness, alcohol dependence, etc.) of the patient rather than on the length of the incision.

Discussion

Conventional hip replacements have improved significantly during the last few decades, and provide excellent pain relief, long implant survival and a low complication rate. Approaches in all directions (posterolateral, anterolateral, anterior, and lateral) have been attempted with a traditional incision length of about 20–35 cm. Recently, the term minimally invasive hip replacement (MIH) has been introduced by different authors and different operative techniques have been developed for reducing the incision length, minimalising soft tissue damage, achieving a faster recovery and better cosmetic results for the patient. Most of the authors [1, 2, 9, 13] claim that only younger, well motivated, low body mass index patients are suitable for this procedure and that “difficult hips” should be excluded. Therefore, some of the studies in the literature are not comparative [1, 3, 10, 11] or they compare the results of a selected group with those of an unselected cohort [5, 16, 18].

The aim of this study was to determine whether it is possible to safely reduce the length of incision in an unselected cohort and what percentage of our patients can be treated by the minimal incision. Furthermore, we compared the clinical and operative data, the rate of complications between the groups of different incision lengths, i.e. mini-incision, midi-incision, and standard-incision.

Like others, we formerly used a comfortable 20–25 cm-long incision for the anterolateral (Watson-Jones) and a 15–25-cm long incision for the lateral (Hardinge [8]) approaches. In this series of 102 total hip arthroplasties using slightly modified instruments, 38 hips were treated by direct lateral mini-incision (less than 10 cm), and a further 43 hips by an incision length between 10 and 14 cm. This means that in experienced hands the length of the incision could be reduced at least by 40–50% in 82% of the patients without increasing the rate of complications.

Some authors have reported less blood loss in the mini-incision group [7, 18], while others observed significantly less intraoperative, but similar total blood loss [9]. The results of our study agree with two other previous controlled studies [20, 21] in that the minimal incision did not have any statistically significant influence on the intraoperative or total blood loss or on the drop in the haemoglobin value postoperatively. Repairing the capsule (capsulorrhaphy) did not decrease the total blood loss. Interestingly, however, the amount of blood loss depended on the type of the prosthesis. Significantly higher volumes were measured in the cementless prosthesis group, which can probably be explained by the higher postoperative bleeding from the bone.

The duration of operations in the mini-incision and standard-incision groups is rather similar in the various reports [7, 20]. Some authors report a shorter operative time in the mini-incision group [9, 18], which corresponds to our experience, after a short learning curve. However, we have to remark that the duration was also strongly influenced by anatomical factors such as dislocation of the hip or previous operations, which needed a longer incision.

In the different operative techniques of minimally invasive hip arthroplasty the authors make every effort to retain the capsule and to perform a capsulotomy and capsulorrhaphy instead of excision of the capsule. This suits the concept of minimal invasiveness, is thought to prevent dislocation of the femoral component, and decreases pain in the early postoperative period without destroying the proprioception of the capsule. We did not find any difference in respect to total bleeding, postoperative major complications (dislocation included) or to reduced pain in the early postoperative period between the two groups. The small number of hips with capsulorrhaphy in our cohort does not allow a correct statistical analysis. In cases of leg length discrepancy, in secondary osteoarthritis and in rheumatic diseases, the capsule of the hip must be exercised.

Although Fehring [6] reported three “catastrophic” complications in MIH, we, like most of the authors [3, 9, 18, 20], did not detect a higher rate of major complications. Our results also support those of Wright et al. [21] and Woolson et al. [20], in finding more hips with slight malpositioning of the cup in the MIH group. This did not lead to postoperative dislocation in our series, but can cause impingement between the components and have an influence on implant wear and thus on the long-term results of the prosthesis. The small “mobile window” of the mini-incision reduces the surgeon’s view of the operating field. Increased use of fluoroscopy might improve component positioning.

Reports on postoperative pain are very controversial in the literature. Most of the advocates of the MIH [1–4, 19] report significantly less postoperative pain while others [7, 20] could not confirm this. In our study the mini-incision group had statistically less pain on the third postoperative day. This can be logically explained by the smaller number of transsected cutaneous sensory nerves in the minimised incision. On the other hand, postoperative pain is very subjective and is influenced by many factors, e.g., level of preoperative pain, patients’ constitution and satisfaction with the cosmetic result.

It was not the aim of our study to create specific objective criteria for the evaluation of the early functional outcome of the operation. Most of the scores used, like the Harris hip score, are not useful in the first postoperative days, therefore most of the authors evaluate the functional results individually. We experienced greater activity and faster recovery in younger healthier patients with either mini- or standard incision than in older patients with comorbidities. Complications such as diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and hypertension influenced the rehabilitation of the patients more than the length of incision.

In conclusion, as a result of minimising the incision in the standard procedure of total hip replacement, we were able to shorten the incision to less than 14 cm in 82% of an unselected patient cohort. The mini-incision (less than 10 cm) technique was performed in 38%. Its results did not differ significantly with regard to intraoperative bleeding, total blood loss, rate of complications, and postoperative recovery from those of the midi- and standard incision groups. Patients experienced less pain in the early postoperative period and were highly satisfied with the cosmetic results. The demand of patients for less invasive surgery with better cosmetic results is understandable. We recommend therefore a smaller incision though not necessarily a mini-incision. This still allows the surgeon to perform the procedure well, without compromising the choice of implants or the otherwise good long-term results.

References

- 1.Berger RA (2003) Total hip arthroplasty using the minimally invasive two-incision approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res 417:232–241 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Berry DJ, Berg RA, Callaghan JJ, Dorr LD, Duwelius PJ, Hartzband MA, Lieberman JR, Mears DC (2003) Symposium: minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Development, early results and a critical analysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 85:2235–2246 [PubMed]

- 3.Bucsi L, Dobos F, Sillinger T (2004) Az “egy metszéses” minimál invazív csípõ totál endoprotézis mûtétjének korai tapasztalatai osztályunkon. Magyar Traumatol 47:274–280

- 4.DiGioia AM III, Plakseychuk AY, Levison TJ, Jaramaz B (2003) Mini-incision technique for total hip arthroplasty with navigation. J Arthroplasty 18:123–128 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dorr LD (2001) The mini-incision hip: building a ship in a bottle. Orthopaedics 27:192–194 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fehring TK, Mason JM (2005) Catastrophic complications of minimally invasive hip surgery. J Bone Joint Surg 87-A:711–714 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Goldstein WM, Branson JJ, Berland KA, Gordon AC (2003) Minimal-incision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 85 [Suppl 4]:33–38 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hardinge K (1982) The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 64:17–19 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Higuchi F, Gotoh M, Yamaguchi N, Suzuki R, Kunou Y, Ooishi K, Nagata K (2003) Minimally invasive uncemented total hip arthroplasty through an anterolateral approach with a shorter skin incision. J Orthop Sci 8:812–817 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kennon RE, Keggi JM, Wetmore RS, Zatorski LE, Huo MH, Keggi KJ (2003) Total hip arthroplasty through a minimally invasive anterior surgical approach. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 85 [Suppl 4]:39–48 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Lester DK, Hehn M (2001) Mini-incision posterior approach for hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol 9:245–253 [DOI]

- 12.Ranawat CS, Ranawat AS (2003) Minimally invasive total joint arthroplasty: where are we going? J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 85:2070–2071 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Rittmeister M, König DP, Eysel P, Kerschbaumer F (2004) Minimal-invasive Zugänge zum Hüft- und Kniegelenk bei künstlichem Gelenkersatz. Orthopäde 11:1229–1235 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Sculco TP (2003) Is smaller necessarily better? Am J Orthop 32:169 [PubMed]

- 15.Sherry E, Egan M, Warnke PH, Henderson A, Eslick GD (2003) Minimal invasive surgery for hip replacement: a new technique using the NILNAV hip system. ANZ J Surg 73:157–161 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Waldman BJ (2002) Minimally invasive total hip replacement and perioperative management: early experience. J South Orthop Assoc 11:213–217 [PubMed]

- 17.Waldman BJ (2003) Advancements in minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Orthopaedics 26 [Suppl 8]:833–836 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Wenz JF, Gurkan I, Jibodh SR (2002) Mini-incision total hip arthroplasty: a comparative assessment of perioperative outcomes. Orthopedics 25:1031–1043 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wohlrab D, Hagel A, Hein W (2004) Vorteile der minimalinvasiven Implantation von Hüfttotalendoprothesen in der frühen postoperativen Rehabilitationsphase. Z Orthop 142:685–690 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Woolson ST, Mow CS, Syquia JF, Lannin JV, Schurman DJ (2004) Comparison of primary total hip replacements performed with a standard incision or a mini-incision. J Bone Joint Surg 86-A:1353–1358 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Wright JM, Crockett HC, Sculco TP (2001) Mini-incision for total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics 7:18–20