Abstract

Atlantoaxial instability (AAI) affects 10–20% of individuals with Down syndrome (DS). The condition is mostly asymptomatic and diagnosed on radiography by an enlarged anterior atlanto-odontoid distance. Symptomatic AAI, which affects 1–2% of individuals with DS, manifests with spinal cord compression. Cervical spondylosis, which is common in DS, also has the potential for cord damage but it has received less attention because paediatric populations were mostly studied. Forty-four Kuwaiti subjects with DS, whose ages were ≥15 years, were evaluated clinically and radiographically. Lateral neck radiographs were taken in the neutral and flexion positions. Asymptomatic AAI was diagnosed in eight subjects (18%) and congenital anomalies of C1–2 were found in five (12%). Five patients had AAI in flexion only while three patients had it in both views. Three patients with AAI had odontoid anomalies contributing to the condition. When assessing AAI, the posterior atlanto-odontoid distance has to be considered because it indicates the space available for the cord. Cervical spondylosis was noted in 16 (36%) subjects. Degenerative changes increased with age, occurred earlier than in the normal population, and affected mostly the lower cervical levels. Half the patients with AAI had cervical spondylosis, a comorbidity that puts the cord at increased risk.

Résumé

L’instabilité de la charnière occipito atloïdienne affecte 10 à 20% des sujets présentant un Down syndrome (trisomie 21). Cette instabilité est souvent asymptomatique et seulement diagnostiquée sur les radiographies qui montrent un élargissement de la distance antérieure atloïdo-odontoide. L’asymptologie de l’instabilité occipito atloïdienne affecte 1 à 2% des sujets présentant un Down syndrome avec des signes manifestes de compression médullaire. La spondylose cervicale qui est habituelle dans le Down syndrome peut potentialiser des lésions de la moelle. 44 sujets Koweitis présentant un Down syndrome dont l’âge était supérieur à 15 ans ont été évalués cliniquement et radiographiquement. Des radiographies de la colonne cervicale de profil ont été effectuées en position neutre et en position de flexion. Une instabilité occipito atloïdienne a été diagnostiquée chez 8 sujets (18%) avec des anomalies congénitales de C1 C2, chez 5 sujets (12%). 5 patients présentaient une instabilité uniquement en flexion et 3 patients présentaient une telle instabilité sur tous les clichés. 3 patients avec une instabilité occipito atloïdienne présentaient des anomalies de l’odontoide aggravant encore les conditions locales. Lorsqu’il existe une instabilité occipito atloïdienne, la distance C1 odontoide doit être évaluée car elle indique l’espace possible pour la moelle. Une spondylolyse cervicale a été relevée chez 16 patients (36% des sujets). Avec l’âge, les lésions dégénératives peuvent évoluer, survenant plus tôt que dans la population normale et peuvent léser les différents niveaux de la colonne cervicale. La moitié des patients avec une instabilité occipito atloïdienne ont une spondylolyse cervicale, avec une co-morbidité entraînant une moelle à risque.

Introduction

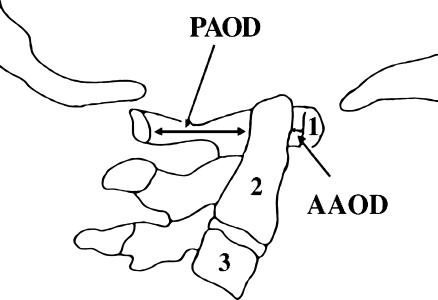

Atlantoaxial instability (AAI), which denotes increased mobility of C2 in relation to C1, occurs more frequently in persons with Down syndrome (DS) than in the general population [17]. The association was first reported in 1961 [23], almost 100 years after DS was described. Although numerous reports followed [11, 17, 21], AAI came into the limelight only in 1983 when the Special Olympics prohibited DS individuals having the condition from participating in certain neck-stressing sports [22]. AAI, which affects 10–20% of individuals with DS, is mostly asymptomatic and is diagnosed using radiography [1, 4, 11, 12]. The instability is recognized through lateral neck radiographs by the presence of an abnormally large anterior atlanto-odontoid distance (AAOD) (Fig. 1). The upper limit of a normal AAOD is 4 mm in subjects who are younger than 15 years and 3 mm in older subjects [3, 10, 11, 19]. The anterior space between the atlas and the axis normally opens in flexion and closes in extension, which is why the AAOD is greater when the neck is radiographed in flexion than it is in neutral or extension positions [16].

Fig. 1.

Drawing of a normal atlantoaxial joint showing the base of the skull, the upper three cervical vertebrae (numbered), and the measurements of the AAOD and PAOD

The danger of AAI is that it becomes symptomatic in 1–2% of individuals with DS when the displaced odontoid impinges the spinal cord [15]. Manifestations include neck discomfort, abnormal gait, change in sphincteric control, upper motor neuron lesion (UMNL), paralysis, and even death. In over 80% of symptomatic patients, this is the end result of chronic gradual instability [15]. In the remaining patients, where it may be preceded by a normal radiograph, it can be precipitated by neck trauma, sports injury, endotracheal intubation, or head and neck surgery [9, 13]. Patients with symptomatic AAI need urgent evaluation and management, which may include posterior fusion of C1 to C2. Patients with the asymptomatic condition need to take precautions to avoid neck injury as well as regular follow-ups to detect any neurological deterioration [16].

The occurrence of degenerative changes in the cervical spine of patients with DS was first reported in 1966 [11]. As expected, these changes increase with age [7, 10, 11], but they occur earlier than in the normal population [10, 14]. Although cervical spondylosis has the potential to cause cervical cord damage [14], it has received less attention in the literature than AAI. This is mainly because most of the studies about cervical spine abnormalities were based on paediatric populations.

Materials and methods

Forty-four Kuwaiti subjects participated in this study. Nineteen subjects were institutionalised and were cared for by the Medical Rehabilitation Center. Twenty-five subjects were living in the community and were drawn from the catchment area of the West Hawalli Polyclinic. The sample consisted of all the DS subjects aged 15 years and above who were receiving primary health care from the two state-run institutes. For the sake of atlanto-odontoid measurements, we considered adults to be those over the age of 15 years [6]. There were 29 males and 15 females ranging in age from 15 to 45 years, with a mean age of 26.64±8.46 years. For comparative purposes, the sample was divided into four age groups: 15–19 years (11 subjects), 20–29 years (20 subjects), 30–39 years (nine subjects), and 40–45 years (four subjects). All subjects had the karyotype pattern of trisomy 21. Ethics Committee approval was granted. Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardian of each subject.

History was obtained from the carers about neck symptoms and the motor skills of the subjects. All subjects underwent physical examination and neck radiographs. The physical examination focused on the neck area and the neurological motor system. Lateral radiographs of the cervical spine were taken in the neutral and flexion positions. The target-film distance was 160 cm and the estimated radiation exposure was approximately 1.5 mR. AAOD was defined as the shortest distance from the posterior aspect of the anterior arch of the atlas to the adjacent anterior surface of the odontoid process (Fig. 1) and was regarded as abnormal if it was >3 mm. The posterior atlanto-odontoid distance (PAOD) was measured as the distance between the posterior aspect of the odontoid process and the anterior aspect of the posterior arch of the atlas and was regarded abnormal if it was <14 mm [5]. The radiographs were also examined for the presence of other congenital anomalies as well as degenerative changes indicating cervical spondylosis (narrowing of interspaces, increased sclerosis, and spurring). The physical examination was carried out by a single researcher and the radiographs were read by another researcher, without either knowing the results of the other’s work. The analysis of the data included descriptive statistics, analysis of variance, and correlation statistics.

Results

The mean AAOD measurement was greater in flexion (2.32±1.7 mm) than in neutral (1.86±1.6 mm) and the difference was very highly significant (p<0.001). AAOD was greater in males than females in both the flexion (2.52±1.8 mm versus 1.93±1.4 mm) and neutral views (1.93±1.8 mm versus 1.73±1.1 mm), but neither difference was significant.

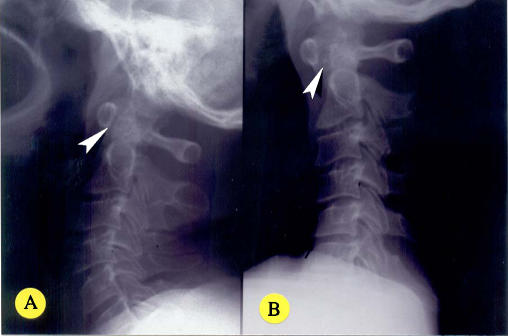

An AAOD of >3 mm, indicating AAI, was noted in eight patients in flexion and in three patients in neutral. Five patients had AAI in flexion only (Fig. 2a–b) and three patients had AAI in both views. None of the cases with radiological AAI had corresponding clinical manifestations. This meant that eight (18%) of our subjects displayed asymptomatic AAI (Table 1). There was a tendency for the frequency of AAI to be greater in men (20.6%) than in women (13%), but the difference was not significant.

Fig. 2.

a–b Lateral view of the cervical spine of a 45-year-old man in neutral (a) and flexion (b). The AAOD is 1 mm in neutral but 4 mm in flexion, indicating AAI (arrowheads). There are degenerative changes in the form of mild narrowing of the C5–6 space and osteophytes

Table 1.

Cervical spine abnormalities according to age groups

| Age range (years) | Subjects (n) | No. with AAI (AAOD > 3 mm) | No. with C1–C2 anomalies | No. (%) with spondylosis | No. with AAI & anomalies | No. with AAI & spondylosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 1 (9%) | ||

| 20–29 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 8 (40%) | 1 | 2 |

| 30–39 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 4 (44%) | 2 | 1 |

| 40–45 | 4 | 1 | 3 (75%) | 1 | ||

| Total | 44 | 8 (18%) | 5 (12%) | 16 (36%) | 3 | 4 |

There was no statistically significant difference between the flexion and neutral views of PAOD measurements. Females had bigger PAOD than males in both positions, but the relationship was not significant. A PAOD of <14 mm was noted in four subjects in flexion and in three of these also in neutral. None of the subjects with reduced PAOD had AAI.

No statistically significant differences were observed in AAOD or PAOD measurements among the various age groups. Correlation analyses between AAOD and PAOD in flexion and neutral found significant correlations (p<0.01) in both positions: flexion r=−0.957 and neutral r=−0.988.

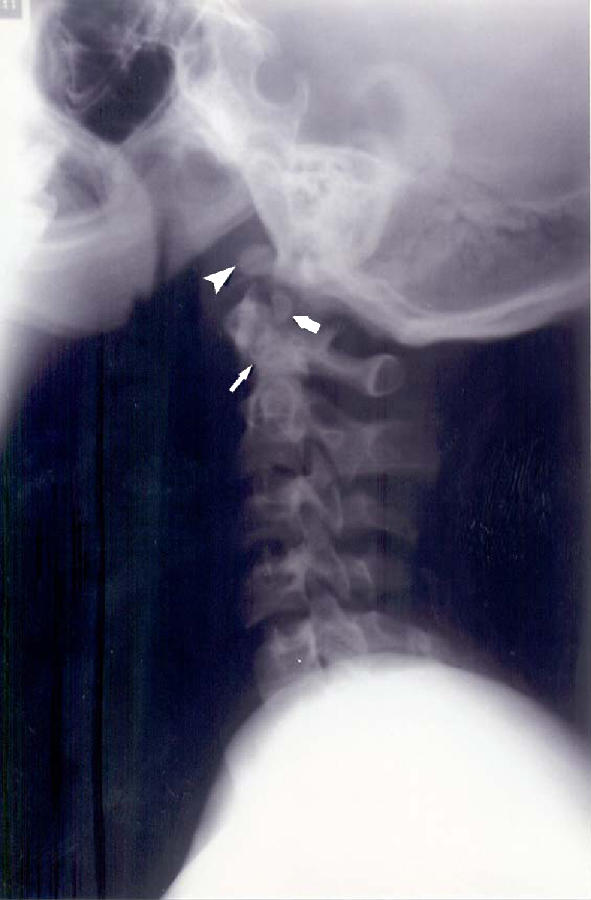

Congenital anomalies of C1 to C2 vertebrae were observed in five patients (12%) (Table 1). One patient, without AAI, had spina bifida of C1. Four patients had anomalies of the odontoid process (odontoid hypoplasia was observed in one, ossiculum terminale in two, and one patient had a combination of odontoid hypoplasia, ossiculum terminale, and os odontoideum) (Fig. 3). Three of the four patients with odontoid anomalies had AAI (Table 1), indicating a good correlation between the two conditions. Two patients had mild subluxations at levels lower than C1–2, one at C3–4 and the other at C4–5. No subject showed subluxation at more than one level.

Fig. 3.

Lateral view of the cervical spine in neutral of a 15-year-old male showing a normal AAOD of 3 mm. There are congenital anomalies: odontoid hypoplasia (slender arrow), os odontoideum (thick arrow), and ossiculum terminale (arrowhead)

Degenerative changes of the cervical spine were noted in 16 (36%) subjects (Table 1) (Figs. 4, 5). Their ages were significantly older than those without spondylotic changes (p=0.002). By analysing the age groups, it was noted that the prevalence of degenerative changes increased with age: 9% of the teens were affected compared with 40% of those in their 20s, 44% of those in their 30s, and 75% of those in their 40s. Two discs were narrowed at C2–C3, five at C3–C4, eight at C4–C5, ten at C5–C6, and six at C6–C7. Four patients with AAI had signs of cervical spondylosis as well.

Fig. 4.

Lateral view of the cervical spine in neutral of a 34-year-old man showing a normal AAOD of 3 mm. There are degenerative changes: narrowing of the C3–4, C5–6, and C6–7 spaces (arrowheads) and posterior osteophytes (arrow)

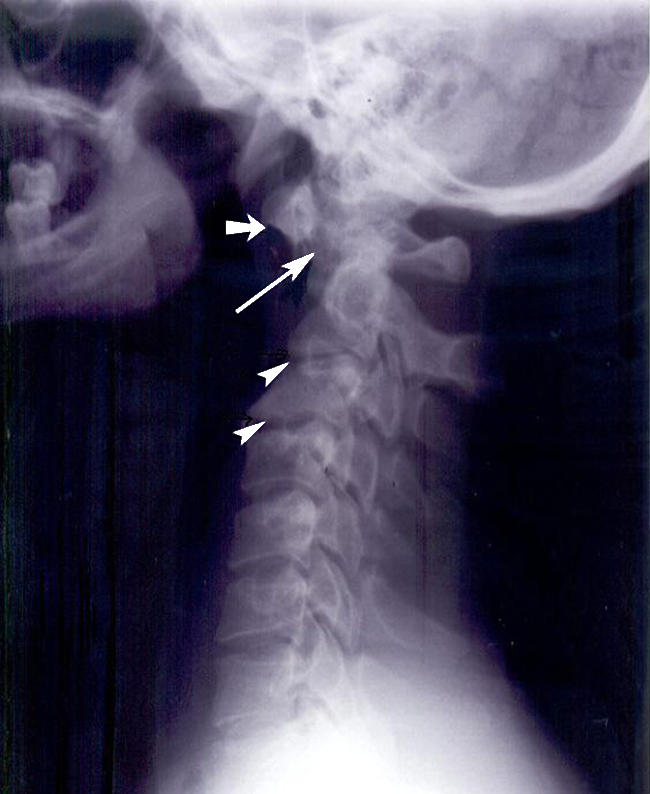

Fig. 5.

Lateral view of the cervical spine in neutral of a 29-year-old man showing an AAOD of 8 mm indicating AAI (long arrow). There is ossiculum terminale (short arrow) and degenerative changes in the form of narrowing at the C2–3 and C3–4 spaces (arrowheads) with anterior and posterior osteophytes

Discussion

The atlantoaxial joint is extremely mobile, but structurally weak and is located between two relatively fixed points, the atlanto-occipital and the C2–C3 joints. It allows 50% of the normal rotation in the cervical spine, but only 10° of both flexion and extension [9]. The joint is supported by a transverse ligament, which keeps the odontoid process close to the anterior arch of the atlas, and a pair of alar ligaments. AAI is primarily caused by laxity of the transverse atlantal ligament. This is part of the general ligamentous laxity characteristic of DS that often results in hyperflexibility of joints [21]. Bony abnormalities of the C1–C2 region, which are common in DS, may play a part in AAI [18]. Upper respiratory infections, which frequently afflict individuals with DS, can cause retropharyngeal ligamentous laxity as the anterior arch of the atlas is only millimeters away from the pharynx [9].

We studied a group of patients 15 years and older, who were predominantly young adults. We followed the example of many studies on AAI in considering adults to be those ≥15 years of age [3, 6, 10, 11]. Otherwise, our sample was mixed containing both sexes living in an institution or in the community. Two possible drawbacks are the relatively small number of subjects and the lack of a control group.

The 18% prevalence of asymptomatic AAI in this study is comparable to the previously reported ranges of 14 to 20% [7, 11, 12, 15, 16, 20]. Since the AAOD was greater in flexion than neutral and no patient had AAI in neutral who did not have it in flexion, it may be enough to take a single lateral neck radiograph in flexion to diagnose AAI. However, a neutral view will offer better visualisation of the other congenital and degenerative abnormalities in the cervical spine. Therefore, we recommend an initial assessment with radiographs in neutral and flexion positions and subsequent follow-up radiographs in the flexed position only. Inexplicably, some patients have AAI on neutral or extension views when it was absent on flexion films [16]. One possible explanation is failure to encourage hyperflexion of the neck which maximizes the atlantoaxial gap [6].

There are some question marks hanging over AAI associated with DS. The natural history of the condition is largely unknown. It has not been firmly established that asymptomatic AAI is a precursor to the symptomatic condition. The correlation between radiological and neurological abnormalities was found to be poor [19]. Even the reliability of radiography in diagnosing AAI has been called into question [20]. Failure to ensure adequate upper neck flexion will produce inaccurate and inconsistent measurements [13]. All this led the American Academy of Pediatrics, in 1995, to withdraw its earlier endorsement of the Special Olympics and recommend screening for the condition before sports activities [2].

Amid these uncertainties, two age-related trends are well defined in cross-sectional studies. First, there is an overall reduction in the atlantoaxial gap with increasing age [6, 10]. This explains why the upper limit of the normal AAOD is greater in children than in adults. Second, there is diminished incidence of AAI with age, even with applying different threshold values for children and adults [6, 10, 21]. However, this observation was not consistent in longitudinal studies. Morton et al. [13] found overall reduction in the atlantoaxial gap over the course of 5 years. Pueschel and Scola [16] found no differences in the AAOD after 3–6 years of follow-up. Paradoxically, one longitudinal study spanning 13 years found an increase in the magnitude of AAI with age [3]. We found no definite pattern of either increase or decrease in the AAOD with age.

We found good negative correlation between the AAOD and PAOD. Measuring the AAOD may not be enough to assess the potential for spinal cord compression. The PAOD needs also to be considered as it indicates the space available for the cord. PAOD may even be a better predictor of the risk for cord compression as it correlates better with subarachnoid space width on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [25]. Patients with radiological AAI but ample PAOD may suffer no cord compression and remain asymptomatic [1]. All of our patients with radiological AAI had normal PAODs which may explain why none was symptomatic.

Abnormalities of the odontoid peg, such as odontoid hypoplasia and the presence of accessory ossicles, may contribute to AAI. Odontoid hypoplasia may cause slippage of the transverse ligament over the superior aspect of the shortened odontoid [10]. Os odontoideum, which appears radiographically as a radiolucent oval ossicle with a smooth dense border of bone, causes loss of strength of the odontoid process as a post for attachment of ligaments [18]. We found a good association between odontoid abnormalities and AAI.

We found spina bifida occulta of C1 in one patient who did not have AAI. Although spina bifida at C1 does not contribute to AAI, it is more often identified in DS children who have AAI than those who do not [18]. Two of our patients had mild subluxation in the midcervical vertebrae, which may carry more risk than AAI, given that the sagittal diameter of the cervical canal is largest at C1 and gradually narrows in size downwards. This lower-level subluxation emphasizes the general nature of ligamentous laxity throughout the spine [12].

We found that degenerative changes in the cervical spine of DS patients increased with age, which is in agreement with other studies [7, 10, 11]. This is not different from the observation in the general population [8], except that these changes occurred at a much earlier age. The prevalence of cervical spondylosis in asymptomatic normal individuals is 5% in the fourth decade of life and 25% in the fifth decade [8]. This is much lower than our figures of 44 and 75%, respectively, but we have to take into consideration that our sample was much smaller. The early occurrence of spondylosis can be a manifestation of an accelerated aging process in the DS patient which also results in the premature onset of dementia. The intervertebral disc space most often affected was C5–6 followed by C4–5, C6–7, C3–4, and C2–3. This predilection for the lower cervical vertebrae is the same pattern found in the general population [8]. This concurs with Olive et al. [14], but contrasts with Miller et al. [12] and Tangerud et al. [24] who found more spondylosis in the upper part of the cervical spine. Jagjivan et al. [10] noted that the older the DS patient, the higher the cervical level affected by degenerative changes. This observation is in line with our results, as most of our patients were young adults. If we apply this relationship between age and cervical level, the differences between our study and the others can be explained by differences in the age of the populations studied.

The finding that half our patients with AAI had degenerative changes in the cervical spine may implicate ligamentous laxity as a common mechanism. Lax ligaments allow more than normal motion between vertebral bodies and may lead to early disc lesions. Identification of cervical spondylosis in DS patients with AAI is important. More interesting than a common aetiology between the two conditions is the potential functional interaction. The restriction of motion lower in the cervical spine, brought on by degenerative changes, places stress on the extremely mobile atlantoaxial joint and may increase the instability. If the prevalence of AAI decreases with advancing age, more attention should be paid to cervical spondylosis, which increases with age, in adults with DS.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Lata Rijhwani and Mrs. Ajitha Suresh, from Kuwait University, for preparation of the figures and doing the statistical analysis, respectively.

References

- 1.Alvarez N, Rubin L (1986) Atlantoaxial instability in adults with Down syndrome: a clinical and radiological survey. Appl Res Ment Retard 7:67–78 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness (1995) Atlantoaxial instability in Down syndrome. Subject review. Pediatrics 96:151–154 [PubMed]

- 3.Burke SW, French HG, Roberts JM, Johnston CE 2nd, Whitecloud TS 3rd, Edmunds JO Jr (1985) Chronic atlanto-axial instability in Down syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 67:1356–1360 [PubMed]

- 4.Cremers MJ, Ramos L, Bol E, van Gijn J (1993) Radiological assessment of the atlantoaxial distance in Down’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child 69:347–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Crosby ET, Lui A (1990) The adult cervical spine: implications for airway management. Can J Anaesth 37:77–93 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Elliott S, Morton RE, Whitelaw RA (1988) Atlantoaxial instability and abnormalities of the odontoid in Down’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child 63:1484–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Fidone GS (1986) Degenerative cervical arthritis and Down’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 314:320 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Friedenberg ZB, Miller WT (1963) Degenerative disc disease of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am 45:1171–1178 [PubMed]

- 9.Harley EH, Collins MD (1994) Neurologic sequelae secondary to atlantoaxial instability in Down syndrome. Implications in otolaryngologic surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 120:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Jagjivan B, Spencer PA, Hosking G (1988) Radiological screening for atlanto-axial instability in Down’s syndrome. Clin Radiol 39:661–663 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Martel W, Tishler JM (1966) Observations on the spine in mongoloidism. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 97:630–638 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Miller JD, Capusten BM, Lampard R (1986) Changes at the base of skull and cervical spine in Down syndrome. Can Assoc Radiol J 37:85–89 [PubMed]

- 13.Morton RE, Khan MA, Murray–Leslie C, Elliott S (1995) Atlantoaxial instability in Down’s syndrome: a five year follow up study. Arch Dis Child 72:115–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Olive PM, Whitecloud TS 3rd, Bennett JT (1988) Lower cervical spondylosis and myelopathy in adults with Down’s syndrome. Spine 13:781–784 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Pueschel SM, Herndon JH, Gelch MM, Senft KE, Scola FH, Goldberg MJ (1984) Symptomatic atlantoaxial subluxation in persons with Down syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop 4:682–688 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Pueschel SM, Scola FH (1987) Atlantoaxial instability in individuals with Down syndrome: epidemiologic, radiographic, and clinical studies. Pediatrics 80:555–560 [PubMed]

- 17.Pueschel SM, Scola FH, Perry CD, Pezzullo JC (1981) Atlanto-axial instability in children with Down syndrome. Pediatr Radiol 10:129–132 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Pueschel SM, Scola FH, Tupper TB, Pezzullo JC (1990) Skeletal anomalies of the upper cervical spine in children with Down syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop 10:607–611 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Roy M, Baxter M, Roy A (1990) Atlantoaxial instability in Down syndrome-guidelines for screening and detection. J R Soc Med 83:433–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Selby KA, Newton RW, Gupta S, Hunt L (1991) Clinical predictors and radiological reliability in atlantoaxial subluxation in Down’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child 66:876–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Semine AA, Ertel AN, Goldberg MJ, Bull MJ (1978) Cervical-spine instability in children with Down syndrome (trisomy 21). J Bone Joint Surg Am 60:649–652 [PubMed]

- 22.Special Olympics Bulletin (1983) Participation by individuals with Down syndrome who suffer from atlantoaxial dislocation condition. Washington, DC, Special Olympics Inc, March 31

- 23.Spitzer R, Rabinowitch JY (1961) Study of abnormalities of skull, teeth, and lenses in mongolism. Can Med Assoc J 84:567–572 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Tangerud A, Hestnes A, Sand T, Sunndalsfoll S (1990) Degenerative changes in the cervical spine in Down’s syndrome. J Ment Defic Res 34:179–185 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.White KS, Ball WS, Prenger EC, Patterson BJ, Kirks DR (1993) Evaluation of the craniocervical junction in Down syndrome: correlation of measurements obtained with radiography and MR imaging. Radiology 186:377–382 [DOI] [PubMed]