Abstract

We analysed 20 patients with 24 knees affected by idiopathic genu recurvatum who were treated with an anterior opening wedge osteotomy of the proximal tibia because of anterior knee pain. We managed to attain full satisfaction in 83% of the patients with a mean follow-up of 7.4 years. The mean Hospital for Special Surgery score was 90.3 (range 70.5–99.5), and the mean Knee Society score score was 94.6 (70–100) for function and 87.7 (47–100) for pain. The mean Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index score for knee function was 87.5 (42–100), for stiffness 82.8 (25–100) and for pain 87.3 (55–100). Radiographs showed a significant increase in posterior tibial slope of 9.4 deg and a significant decrease of patellar height according to the Blackburne–Peel method of 0.16 postoperatively. No cases of non-union, deep infection or compartment syndrome were seen. No osteoarthritic changes in the lateral or medial knee compartment were found with more than 5 years’ follow-up in 16 patients with 19 affected knees. Three out of the four dissatisfied patients had a patella infera which led to patellofemoral complaints. One patient in the study underwent a secondary superior displacement of the patella with excellent results. We conclude that in a selected group of patients with idiopathic genu recurvatum and anterior knee pain an opening wedge osteotomy of the proximal tibia can be beneficial.

Résumé

Nous avons analysé 20 patients représentant 24 genu recurvatum idiopathiques avec des douleurs antérieures du genou. Ces patients ont été traités par une ostéotomie d’ouverture antérieure de l’extrémité supérieure du tibia. Le suivi moyen a été de 7,4 ans. Le pourcentage de satisfaction a été de 83%. Le score HSS a été de 90,3 (70,5 à 99,5), les scores de la « Knee Society » a été de 94,6 ( 70 à 100) pour le score fonction et de 87,7 (47 à 100) pour le score douleur. L’index WOMAC, fonction du genou a été de 87,5 (42 à 100), pour la raideur 82,8 (25 à 100) et pour la douleur 87,3 (55 à 100). Les radiographies ont montré une augmentation significative de la pente tibiale postérieure de 9,4°, une diminution significative de la hauteur de la rotule. Il n’a été constaté aucun cas de pseudarthrose, d’infection, de syndrome compartimental. Il n’a pas été constaté non plus de modification dégénérative des compartiments internes ou externes du genou à plus de 5 ans de recul chez 16 patients revus avec 19 genoux opérés. 3 patients sur les 4 non satisfaits ont présenté une patella infera entraînant des phénomènes douloureux fémoro-patellaires. Un patient dans cette étude a bénéficié d’une transposition avec ascension de la rotule avec un excellent résultat. Nous concluons pour ce nombre de patients non sélectionnés, présentant un genu recurvatum avec douleur antérieure du genou que l’ostéotomie d’ouverture antérieure de l’extrémité supérieure du tibia est une intervention bénéfique.

Introduction

Anterior knee pain is a well-known symptom in sports medicine frequently associated with overuse. Patellofemoral disorders such as knee valgus malalignment, patella-tracking abnormalities, quadriceps insufficiency and chondromalacia of the patella and trochlea are most commonly found as causes of anterior knee pain. Also patellar tendon-related complaints—patellar tendinopathy, Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome or Osgood-Schlatter disease—contribute significantly to the anterior knee pain syndrome. Furthermore, anterior meniscal injury, impingement of the anterior cruciate ligament, infrapatellar bursitis and referred hip pain should not be overlooked.

Fat pad impingement is an underestimated cause of anterior knee pain and shows similarity to both patellofemoral syndrome and patellar tendinopathy [14]. The main source of pain is thought to be constant stretching of the joint capsule due to the impingement [13]. This phenomenon will be seen especially when the knee is continuously hyperextended in patients with a genu recurvatum. The clinical features of the hyperextended knee anterior impingement syndrome are dull, diffuse pain, difficult to localize and provoked by “locking” the knee in full extension. Physical examination reveals pain on palpation of the anterior joint line and Hoffa’s pad. Non-operative measures such as muscle strength training and anti-hyperextension bracing are the first options for treatment. If an anti-hyperextension brace results in significant pain reduction without complete resolution of the knee complaints, anti-recurvatum tibial osteotomy can be an option. The osteotomy is intended to end the repetitive impingement by redressing knee extension. The aim of this study was to report on the medium-term results of opening wedge anti-recurvatum high tibial osteotomy for anterior knee pain in idiopathic hyperextension knees.

Materials and methods

Between 1988 and 2005 we performed an anterior opening wedge osteotomy of the proximal tibia in 27 knees of 22 patients. By increasing the tibial slope and consequently reducing knee extension the goal was to relieve pressure on the anterior cartilage of the tibia plateau and to reduce the fat pad impingement resulting from continuous hyperextension of the knee.

Preoperatively all patients had an idiopathic genu recurvatum with an angle of 15 deg or more and complaints of anterior knee pain [16]. All patients were extensively trained to enhance muscle strength to counteract hyperextension and thus reduce anterior knee pain. At the same time, the effect of an anti-hyperextension brace (Swedish knee cage, Basko Healthcare) was evaluated in every patient. When bracing significantly reduced anterior knee complaints a tibial osteotomy was proposed.

The operation consisted of an opening wedge osteotomy of the proximal tibia cranial to the tuberosity [3, 5, 12]. The approach was by a transverse incision leaving the peripheral capsuloligamentous structures intact. The osteotomy was performed with chisels without detachment of the tubercle. In all operations we used ipsilateral iliac crest cortical and cancellous bone wedges, and in 14 knees we also tried to correct an associated valgus deformity. In four knees extra fixation with staples was used. Postoperatively all patients were fitted with an above knee cast without weight-bearing for 4 weeks and then with weight-bearing for 4 weeks.

One patient was lost to follow-up and one patient had no complaints but refused evaluation. Seventeen women and three men with 24 affected knees were evaluated after an average follow-up of 7.4 years (range 1–16 years). Sixteen patients with 19 knees had more than 5 years’ follow-up. The mean age was 32.7 years (range 19–49 years).

All patients were asked to assess whether they were satisfied with their operation and whether they would have the operation again given the same circumstances. Knee pain and iliac crest donor site pain were measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS; 0–10). Knee function was evaluated by the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score, the Knee Society score (KSS) and the Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) score. Radiography of the knee included an anteroposterior radiograph in the standing position to measure the anatomical and the oblique joint line axis. A true lateral radiograph of the knee in at least 30 deg of flexion was used to determine the length of the patella tendon according to two methods: Insall–Salvati and Blackburne–Peel [2, 8]. The inclination angle of the tibial plateau was measured on a lateral radiograph according to Moore and Harvey [15]. The SPSS program was used for the statistical analyses. A p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All osteotomies showed complete union and no deep infections were seen. Seventeen patients with 20 affected knees (83%) were satisfied with the operation. The postoperative functional outcomes for all patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean functional outcome post anterior opening wedge osteotomy of the proximal tibia in 24 knees of 20 patients

| Score (0–100) | Mean±SD | |

|---|---|---|

| HSS | 90.3±9.0 | |

| KSS | Function | 94.6±8.9 |

| Pain | 87.7±18.0 | |

| WOMAC | Function | 87.5±17.7 |

| Stiffness | 82.8±27.8 | |

| Pain | 87.3±17.8 |

The average knee flexion/extension in the whole group was 138/2/0 deg. The average knee VAS score was 2.2 (range 0–8) and the VAS score for the iliac crest donor site was 1.7 (0–7). The mean HSS score was 90.3 (70.5–99.5), the mean KSS for function was 94.6 (70–100) and the mean KSS for pain was 87.7 (47–100). The mean WOMAC score for knee function was 87.5 (42–100), for stiffness 82.8 (25–100) and for pain 87.3 (55–100).

The radiographic outcomes for all patients are displayed in Table 2. The average preoperative femorotibial anatomical axis did not change significantly from 4.7° (0–9°) valgus to 4.5° (0–10°) valgus postoperatively. The oblique joint line axis changed significantly with a medial inclination increase from an average 2.5° (−2° to +5°) to an average 3.8° (−3° to +9°) after surgery.

Table 2.

Mean radiographic outcome pre-and post anterior opening wedge osteotomy of the proximal tibia in 20 patients with 24 knees treated

| Parameter | Preoperative | Postoperative | Difference pre-/postoperative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femorotibial anatomical axis, mean±SD | 4.7°±2.6 | 4.5°±.1 | 0.22°±2.4 |

| Oblique joint line axis, mean±SD | 2.5°±1.6 | 3.8°±2.6 | 1.38°±2.3a |

| Tibial posterior inclination (MH), mean±SD | 11.7°±3.5 | 21.1°±5.7 | 9.4°±5.1a |

| Patellar height (IS), mean±SD | 1.2±0.2 | 1.2±0.1 | 0.04±0.15 |

| Patellar height (BP), mean±SD | 0.9±0.1 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.16±0.19a |

MH, Moore–Harvey tibial plateau inclination measurement method; IS, Insall–Salvati ratio; BP, Blackburne–Peel ratio

aStatistically significant

The postoperative tibial slope measured 21.1° (9–29°) of posterior inclination which was a significant increase of 9.4° over the average preoperative tibial slope of 11.7° (6–19°) of posterior inclination. The average patellar height was 1.2 preoperatively and remained at 1.2 after tibial osteotomy according to the Insall–Salvati method. The Blackburne–Peel method, however, showed a significant decrease in patellar height from 0.9 (0.67–1.30) before operation to 0.7 (0.26–1.52) thereafter.

No patients demonstrated significant osteoarthritic changes in the medial or lateral compartments according to the radiographic grading system of Kellgren. One patient showed patellofemoral osteoarthritic changes with a patella infera. However, 5 years before the tibial osteotomy this patient had been treated for patellofemoral complaints with a tuberosity distal transfer for patella alta. One patient had the tibial tubercle transferred proximally 3 years after opening wedge anti-recurvatum osteotomy for patella infera. After this the patient was completely satisfied and demonstrated no knee pain during evaluation. Two years after surgery one patient suffered from an anterior cruciate ligament rupture after a sports accident. She was treated non-operatively with muscle strengthening and a knee brace. One patient developed a complex regional pain syndrome in the ipsilateral foot. Two patients were found to have meralgia paraesthetica as a result of injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve while harvesting the iliac bone grafts.

Discussion

Anterior knee pain is possibly the most common presenting symptom in clinical sports medicine [14]. The patellofemoral joint structures contribute mainly to the pain felt in the anterior part of the knee. The two most common causes of anterior knee pain are the patellofemoral syndrome and patellar tendinopathy. Structures about the patellofemoral joint such as cartilage, subchondral bone, synovial plicae, retinacula and capsule, alone or in combination, can also be a source of anterior knee pain [13].

Infrapatellar fat pad impingement is an underdiagnosed cause of anterior knee pain that may mimic features of both patellofemoral syndrome and patellar tendinopathy. McConnell stated that 78% of her patients presenting with patellar tendonitis had an irritation of the fat pad. The boundaries of the fat pad, first described by Hoffa, are intra-articular but extra-synovial. The structure is heavily vascularized and has a rich nerve supply marked by substance P-immunoreactive nerve fibers and type IVa free nerve endings. The close anatomical relationship to the patellar tendon and the lateral superficial oblique retinaculum make the fat pad a frequent source of pain [1, 6, 14]. Patients who engage in sports which strain the knee in extension and patients with conditions such as patellar dysplasia or genu recurvatum are believed to be especially prone to infrapatellar fat pad impingement and anterior knee pain [1].

The term genu recurvatum describes a knee with hyperextension of the tibia on the femur. A valgus deformity is often present. The condition can be congenital or acquired. Dejour found three types of genu recurvatum:

A pure osseous deformity, in most cases caused by damage to the growth plate of the tibial tubercle.

A global or asymmetrical hyperextension of the knee as a result of traumatic or gradual stretching of the soft tissue structures.

A mixed-type deformity resulting from alteration of the bony and the soft tissue elements. This pattern can be seen following poliomyelitis [5].

Moroni recognized a fourth idiopathic type of genu recurvatum when the cause is unknown. This condition is often bilateral and symmetrical. When the angle of recurvation exceeds 15 deg it is considered pathological [16].

One of the most frequent symptoms of genu recurvatum is pain. One of the reasons could be chronic inflammation of the infrapatellar fat pad caused by repetitive microtrauma every time the knee is hyperextended. The continuous pinching action of the enlarged fat pad on the overlying synovium with the risk of impingement behind the patellar tendon can lead to anterior knee pain.

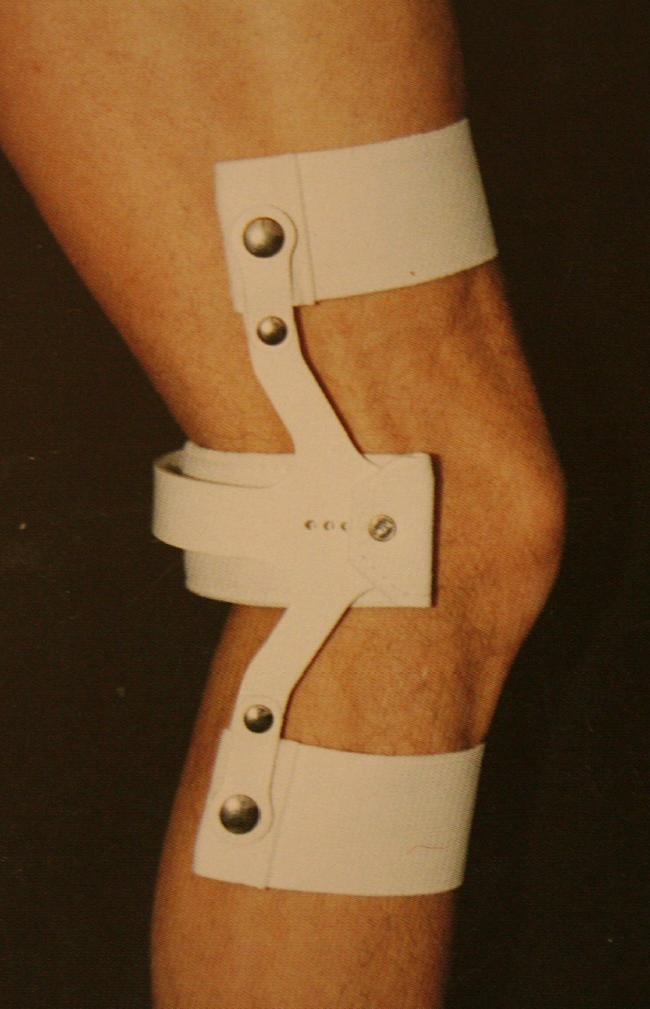

The treatment of choice is non-operative because the majority of patients with anterior knee pain can be treated successfully without an operation. Our patients underwent an extensive regime of simultaneous hamstrings and quadriceps muscle training by the physiotherapist to counteract hyperextension of the knee. A Swedish knee cage (Fig. 1), which prevents knee extension better than a regular brace, was used in persisting cases. All patients who underwent an anti-recurvatum opening wedge tibia osteotomy in this study were first treated with a Swedish knee cage, and only when bracing reduced anterior knee complaints was a tibial osteotomy proposed.

Fig. 1.

Swedish knee cage (Basko Healthcare)

Our aim was to increase the tibial slope enough to correct any hyperextension deformity to neutral. Very few recommendations are made in the literature regarding optimal correction, but Dejour advised correction of the recurvatum deformity to normal alignment in the sagittal plane [5]. We also tried to correct valgus malalignment with iliac crest bone wedges diminishing in size from lateral to medial.

Moore and Harvey described a normal tibia plateau angle of 14 deg with a standard deviation (SD) of ±3.6 deg down slope [15]. We increased the tibial slope significantly by a mean of 9.4 deg of posterior inclination in our genu recurvatum population, from 11.7 deg SD±3.5 to 21.1 deg ±SD 5.7. This led in our series to a mean knee extension deficit of 2 deg with excellent functional outcomes as measured by the HSS score (90.3/100), the KSS (94.6/100) and the WOMAC score (87.5/100).

Sagittal plane re-alignment can contribute to knee stability in ligament-deficient knees. On the other hand, an increase in posterior inclination of the tibia in the ligament-sufficient knee can lead to increased load on the intact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). In this young and active group of patients with a mean age of 33 years we only found one patient with an ACL deficiency, who sustained a sports accident 2 years after surgery. She was treated non-operatively with muscle strengthening and a knee brace.

In more than half of the knees we tried to correct an associated valgus malalignment with different-sized iliac crest bone wedges. The overall femorotibial anatomical axis was not significantly changed, but the oblique knee joint line axis in the whole patient population changed significantly from a mean of 2.5 deg to a mean of 3.8 deg medial inclination. There are no reports on the threshold of the obliquity of the knee joint line producing complaints. Paley suggested that an increase greater than 2 deg of medial inclination in the frontal plane of the knee joint is pathological [18]. In our study we found no functional or radiological consequences of this increase in knee joint line obliquity. With a follow-up of more than 5 years in 16 patients with 19 affected knees we did not see any osteoarthritic changes in the medial or lateral knee compartments on the standing knee radiograph.

Since the tibial tubercle was not detached we did not see any change in patellar height as measured by the method of Insall and Salvati. Nevertheless, Brouwer et al. reported that an increase of tibial slope after open wedge tibial osteotomy above the patellar ligament insertion is significantly associated with patella baja according to the Insall–Salvati method [4]. Using the Blackburne–Peel method we found a significant loss of patellar height ratio of 0.16. The retrospective study by Naudi et al. noted a similar average decrease of patella height of 0.17 using the Blackburne–Peel ratio in a population treated with opening wedge high tibial osteotomy for hyperextension–varus thrust symptoms. They found no correlation between patella baja and functional outcome [17].

However, patella infera occurs after performing anterior opening wedge osteotomy of the tibia. The patellofemoral load will probably be increased by the change in contact area [9]. This can lead to patellofemoral complaints with functional loss.

Three of the four dissatisfied patients in this study had radiographic patella infera (Blackburne–Peel ratio less than 0.67) with a positive patellar grind test on physical examination. Restoring patellar height may be beneficial, as one patient in this case study had complete resolution of his postoperative patellofemoral complaints after secondary superior displacement of the tibial tubercle.

In this case study no cases of intra-articular fracture, deep infection or compartment syndrome were seen and all osteotomies united. On the iliac crest pain VAS (0–10) our group had a low mean score of 1.7, with four patients (17%) having a score of five or more.

Many patients can have persisting iliac crest site donor pain long after their recipient site has ceased to worry them [11]. Goulet even reported donor site pain in 18.3% of his patients at 2 years or more after operation [7]. Although we followed standard technique in harvesting iliac bone, two patients complained of dysaesthesia in a large area on the lateral aspect of the thigh. It has been reported that the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve takes an anomalous course over the anterior crest up to 2 cm lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine in 10% of people [11]. The use of bone substitutes such as hydroxyapatite wedge implantation may avoid such complications in the future [10].

Although we know that this study was a retrospective analysis with all the attendant shortcomings, we conclude that in a selected group of patients with idiopathic genu recurvatum and anterior knee pain an anti-recurvatum opening wedge osteotomy can be beneficial. We obtained an excellent overall functional result in 83% of the patients with this specific diagnosis of anterior knee pain.

References

- 1.Biedert RM, Sanchis-Alfonso V (2002) Sources of anterior knee pain. Clin Sports Med 21:335–347 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Blackburne JS, Peel TE (1977) A new method of measuring patellar height. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 59(2):241–242 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Brett AL (1935) Operative correction of genu recurvatum. J Bone Joint Surg 17:984–989

- 4.Brouwer RW, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, van Koeveringe A, Verhaar JAN (2005) Patella height and inclination of tibial plateau after high tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 87(9):1227–1232 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dejour D, Bonin N, Locatelli E (2000) Tibial antirecurvatum osteotomies. Oper Techni Sports Med 8:67–70 [DOI]

- 6.Duri ZAA, Aichroth PM, Dowd G (1996) The fat pad: clinical observations. Am J Knee Surg 9(2):55–66 [PubMed]

- 7.Goulet JA, Senunas L, DeSilva G, Greenfield MLVH (1997) Autogenous iliac crest bone graft, complications and functional assessment. Clin Orthop 339:76–81 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Insall J, Salvati E (1971) Patella position in the normal knee joint. Radiology (1):101–104 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Koshino T (1991) Changes in patellofemoral compressive force after anterior or anteromedial displacement of tibial tuberosity for chondromalacia patellae. Clin Orthop 266:133–138 [PubMed]

- 10.Koshino T, Murase T, Takagi T, Saito T (2001) New bone formation around porous hydroxyapatite wedeg implanted in opening wedge high tibial osteotomy in patients with osteoarthritis. Biomaterials 22:1579–1582 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kurz LT, Garfin SR, Booth RE (1989) Harvesting autogenous iliac bone graft: a review of complication and techniques. Spine 14:1324–1331 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lexer E (1931) Wiederherstellungschirurgie, 2nd edn. Barth, Leipzig

- 13.Magi M, Branca A, Bucca A, Langerame V (1991) Hoffa disease. Ital J Orthop Traumatol 17(2):211–216, Jun 1991 [PubMed]

- 14.McConnell J, Cook J (2005) Anterior knee pain. Clinical sports medicine, Chapter 24

- 15.Moore TM, Harvey JP Jr (1974) Roentgenographic measurement of tibial plateau depression due to fracture. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 56:155–160 [PubMed]

- 16.Moroni A, Pezzuto V, Pompili M, Zinghi G (1992) Proximal osteotomy of the tibia for the treatment of genu recurvatum in adults. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 74:577–586 [PubMed]

- 17.Naudi DDR, Amendola A, Fowler PJ (2004) Opening wedge high tibial osteotomy for symptomatic hyperextension-varus thrust. Am J Sports Med 32:60–70 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Paley D (2003) Principles of deformity correction. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York