Abstract

The chiral, nucleophilic catalyst TADMAP (1) has been prepared from 3-lithio-4-dimethylamino-pyridine (5) and triphenylacetaldehyde (3), followed by acylation and resolution. TADMAP catalyzes the carboxyl migration of oxazolyl, furanyl, and benzofuranyl enol carbonates with good to excellent levels of enantioselection. The oxazole reactions are especially efficient, and are used to prepare chiral lactams (23) and lactones (30) containing a quaternary asymmetric carbon. TADMAP-catalyzed carboxyl migrations in the indole series are relatively slow and proceed with inconsistent enantioselectivity. Modeling studies (B3LYP/6-31G*) have been used in qualitative correlations of catalyst conformation, reactivity, and enantioselectivity.

Introduction

Chiral nucleophilic catalysis is an important category of organocatalysis and has been demonstrated to mediate a variety of transformations including phosphorylation, sulfonylation, Baylis-Hillman reactions, and ketene addition reactions.1,2 However, nucleophilic catalysis is most often used in acyl transfer reactions, and a variety of chiral catalysts have been developed to effect enantioselective variants. Beginning with Wegler’s original work using alkaloids,3a catalysts have included chiral trialkylamines,3 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) derivatives,4–10 synthetic peptides,11,12 amidines,13 nucleophilic heterocyclic carbenes,14,15 and phosphines.16

Chiral DMAP analogs have been particularly attractive targets since DMAP itself is highly reactive, easy to handle, and catalytically active for a variety of transformations.2a–d,g Strategies for making chiral DMAP analogs have included stereogenic substitution at the C(2) and C(3) positions on the pyridine ring as well as chirality in the dialkylamino group. The most successful strategy so far (Fu et al.) utilizes a planar-chiral DMAP analog, where the chiral information is communicated to the active pyridine ring nitrogen via a ferrocene group fused to the pyridine core.5 This catalyst is capable of high enantioselectivity in a variety of transformations,

Work in our laboratory has centered on finding a chiral DMAP-based catalyst that would be easily accessible as well as highly enantioselective.4 Design considerations are limited by the presence of two mirror planes of symmetry in the DMAP core, and by a total of three sites, C(2), C(3), and C(4)-N, where chiral substituents might be attached. Substitution at C(2) is problematic because of the expected decrease in catalytic reactivity due to steric hindrance,4a,c,17 and the remaining sites at C(3) and C(4)-N are not ideal because chiral substituents would have to communicate stereochemical information across a substantial distance. Nevertheless, important progress has been made and enantioselective DMAP catalysts have been developed in both structural categories by Fuji et al., C(4)-N,6 and Spivey et al., C(3).7a,c,d Several other chiral DMAP catalysts based on variations of the C(4)-N substituent have also been disclosed.7b,8–10

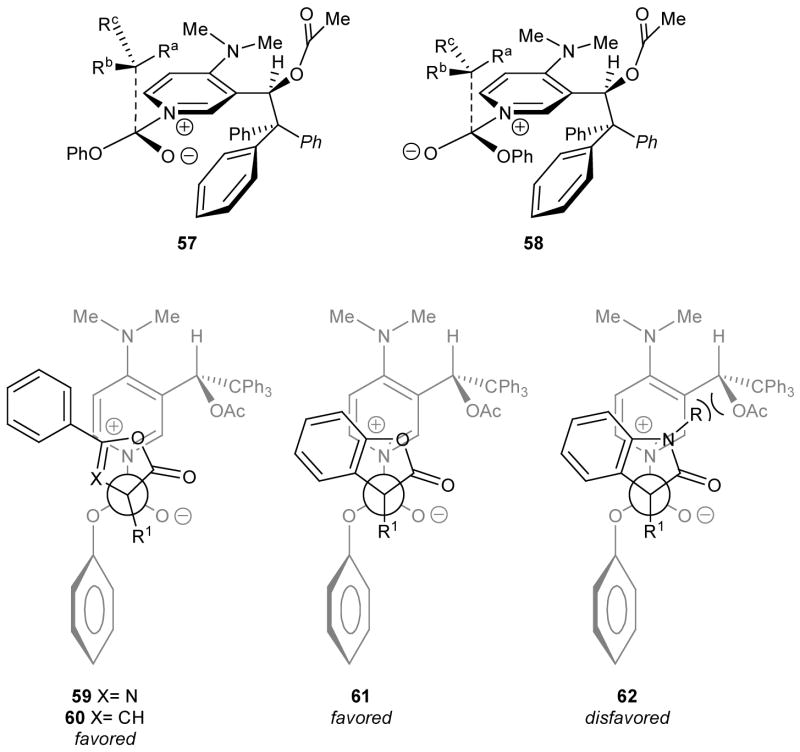

With the goal of developing shorter routes to potentially selective catalysts, we chose to study a new class of chiral C(3) substituted pyridine derivatives 1 (Figure 1). Placing the substitution at C(3) puts it as close to the nucleophilic pyridine nitrogen as possible without hindering the catalytically active site. It was hypothesized that the corresponding N-acyl pyridinium intermediate 2 would prefer a geometry where the dialkylamino group is nearly coplanar with the pyridine ring, thereby maximizing nN→π electron delocalization. The benzylic substituents would rotate to place the bulky, conformationally degenerate trityl group over one face of the pyridine ring, thus ensuring that one face of the pyridinium ring is always “blocked” by a phenyl group. The benzylic hydrogen on the acylated catalyst 2 would be oriented towards the 4-dialkylamino group in order to minimize steric interactions. In this conformer, the acetoxy group creates a chirotopic environment on the “open” face of the pyridine ring. Retrosynthetically, 1 would be available from a 3-metallo-4-(dialkylamino)pyridine and a triarylacetaldehyde. This disconnection provides rapid access to racemic 1, and has potential for asymmetric synthesis as well as variation of catalyst substitution.

Figure 1.

C-3 Substituted chiral DMAP derivatives

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Enantiomerically Pure TADMAP 1

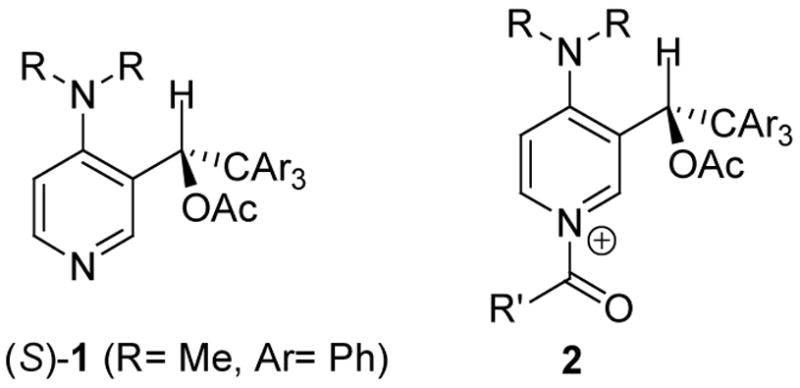

The synthesis of racemic 1 (“TADMAP”; for 2,2,2-Triphenyl-1-Acetoxyethyl-DMAP) began with the conversion of commercially available triphenylacetic acid to triphenylacetaldehyde 318 using a two-step reduction/oxidation sequence (LiAlH4; TPAP/NMO; Scheme 1). Pyridinium chlorochromate (PCC) was originally used for the oxidation,18 but this required chromatography. In contrast, TPAP/NMO gave crude 3 that could be crystallized to purity on multigram-scale. Aldehyde 3 was then treated with the aryllithium reagent 5 from 3-bromo-4-(dimethylamino)pyridine 419 and tBuLi, and the resulting lithium alkoxide 6 was quenched with acetic anhydride to afford racemic 1 (4 steps, 37% overall from triphenylacetic acid on gram scale). No chromatography was required until the final aryllithium coupling reaction.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of TADMAP 1.

It was necessary to perform the addition of 5 to 3 under dilute conditions (~0.10 M) to avoid precipitation of 5. Reversing the order of addition and adding 3 to the precipitated 5 produced a modest yield of 1 on 200 mg scale (43%), but only 13% on 800 mg scale. Even under the former (dilute) conditions, it was necessary to use 1.5 equivalents of 5 to achieve complete conversion of 3, and it was important to add 5 with vigorous stirring and careful temperature control at −78 °C to minimize the formation of byproducts. If the alkoxide 6 was quenched with water instead of acetic anhydride, the products included triphenylmethane and trace amounts of aldehyde 8 in addition to the pyridyl alcohol 7. Evidently, the alkoxide 6 fragments to give trityllithium and 8 in the latter experiment. Fragmentation of the triphenylmethyl group did not occur when the analogous alkoxide intermediate was generated from 3 and phenyllithium, suggesting that synergistic electron donation involving both the alkoxide and the arene ring in 6 is necessary to generate enough “push” to release the basic trityl anion (pKaMeCN = 44, pKaDMSO = 30.6).20

With multi-gram quantities of racemic catalyst 1 in hand, resolution of the enantiomers was necessary. Initially, small quantities of rac-1 were resolved by HPLC over chiral support, but this laborious process was not suited to gram-scale synthesis. Fortunately, enantiomerically pure TADMAP 1 was readily obtained via classical resolution. Treatment of rac-1 with 0.5 equivalents of (−)-camphorsulfonic acid (CSA) in warm toluene produced the enantiomerically enriched salt 9. After neutralization with NaOH, the procedure was repeated on the scalemic material to give (R)-1 with >99% ee. The (S)-1 enriched mother liquor of the initial crystallization was treated analogously with (+)-CSA, producing (S)-1 in >96% ee. Using this procedure, 7.4 g of racemate was resolved to give 0.7 g of (R)-1 (>99% ee) and 1 g of (S)-1 (98.3% ee), with 4.7 g of scalemic 1 available for further resolution (>85% recovery over the crystallization sequence).

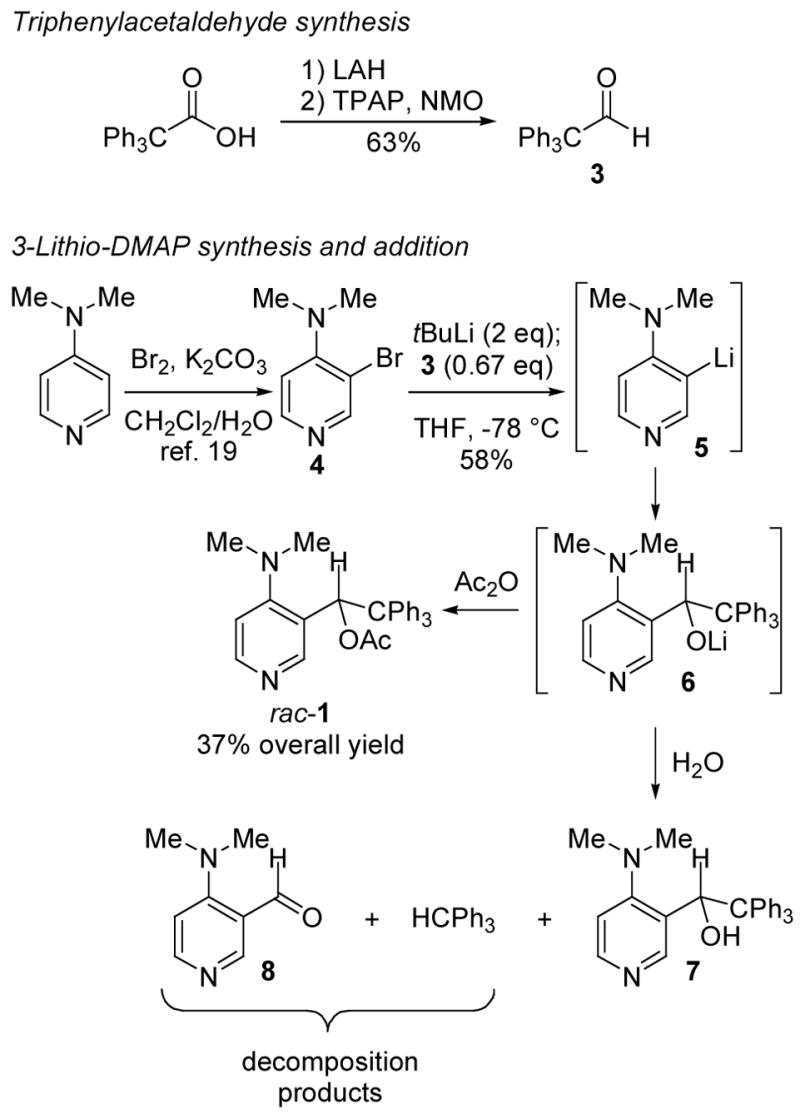

In order to better understand the three-dimensional structure of catalyst 1, the N-carboxyl pyridinium salt 2 (Ar= Ph, R= Me, R′= OPh) was studied using computational methods. Electron donation from the C-4 nitrogen into the pyridine ring was expected to play a major role in conformational bias. Therefore, DFT (B3LYP/6-21G*) methods were used that take mesomeric stabilization into account.21 The choice of the N-phenoxycarbonyl pyridinium environment for computation was made to address the best results of carboxyl migration experiments to be discussed later. Three energy minima were located having nearly equal energies (Table 1). As expected, the trityl group was oriented over one face of the pyridine ring in the favored conformers to minimize steric interactions, and the sidechain ethyl backbone was in a staggered conformation. The acetate adopts the standard secondary ester geometry with the carbonyl group nearly eclipsing the adjacent benzylic C-H bond and the dialkylamino group in each minimum is nearly coplanar with the pyridinium ring.

Table 1.

Energy minima for N-phenoxycarbonyl pyridinium ion 2a

| Entry | Geometryb | Erel (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

0.17 |

| 2 |

|

0.13 |

| 3 |

|

0.00 |

Ar= Ph, R= Me, R′= OPh

Energy minima located using DFT computations (B3LYP/6-31G*)

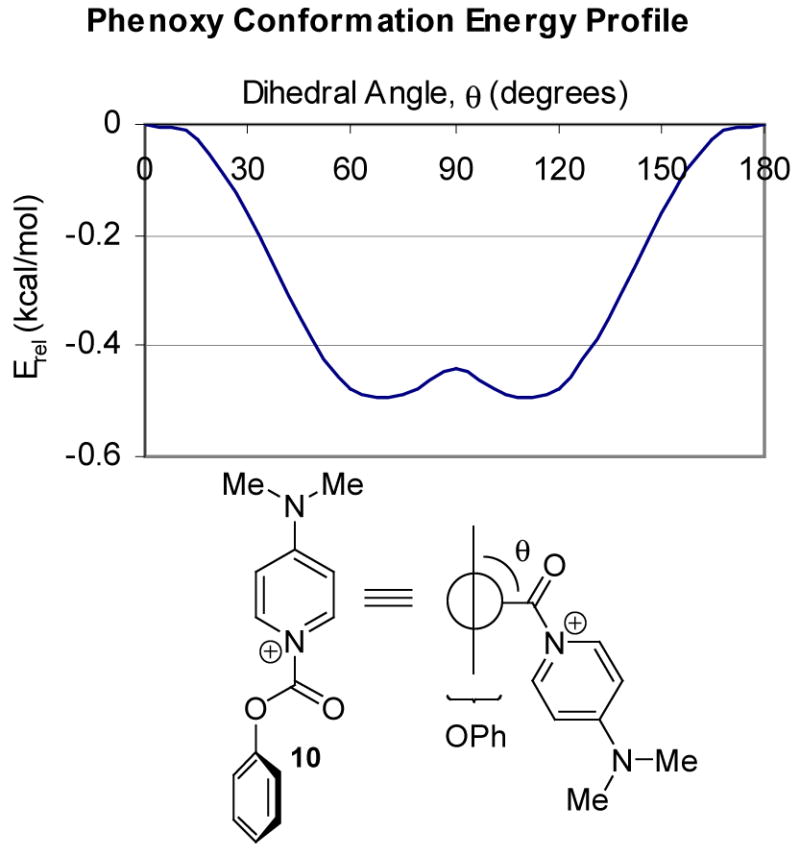

The energy minima have similar geometry, but differ in conformational details involving the phenoxycarbonyl group. Thus, both N-CO rotamers were found (Table 1, entry 1 vs. entries 2 and 3), and the phenyl ring of the phenoxycarbonyl subunit was twisted out of the carbonyl plane. The same geometry was also found as an energy minimum for the unsubstituted DMAP-derived cation 10 (Fig. 2, θ = ca. 60°), and was favored by ~0.5 kcal/mol over the coplanar structure (Figure 2, θ = 0°). The conformational profile for 10 also showed a small energy maximum where the phenyl ring is perpendicular to the carbonyl/pyridine plane (θ = 90° ).

Figure 2.

N-Phenoxycarbonyl-DMAP energy profile (B3LYP/6-31G*)

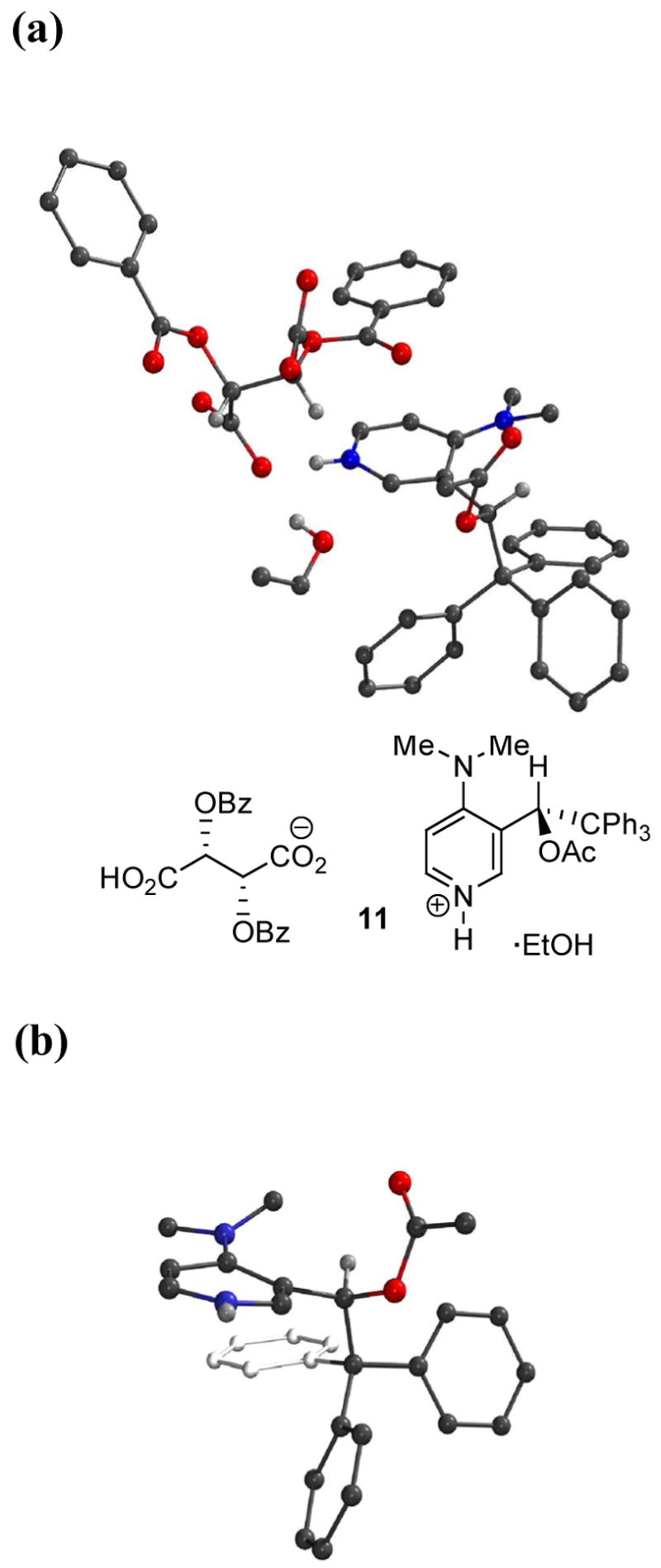

Although TADMAP 1 was resolved with CSA, the resulting crystals were not suitable for X-ray analysis. Dibenzoyl-(L)-tartaric acid, on the other hand, was ineffective as a resolving agent, but crystallization of a 1:1 mixture of resolved (+)-1 and dibenzoyl-(L)-tartaric acid gave suitable crystals of the salt 11 (Figure 3). This allowed assignment of the absolute stereochemistry as well as the solid state conformation, and revealed good qualitative agreement with features of the computed energy minima (Table 1), including the coplanar dialkylamino group, the trityl group extending over one face of the pyridine, and the relative orientation of the benzylic hydrogen.

Figure 3.

(a) Structure of TADMAP·dibenzoyl-(L)-tartaric acid·EtOH 11 (b) 11 from a different perspective with counterion and ethanol atoms omitted.

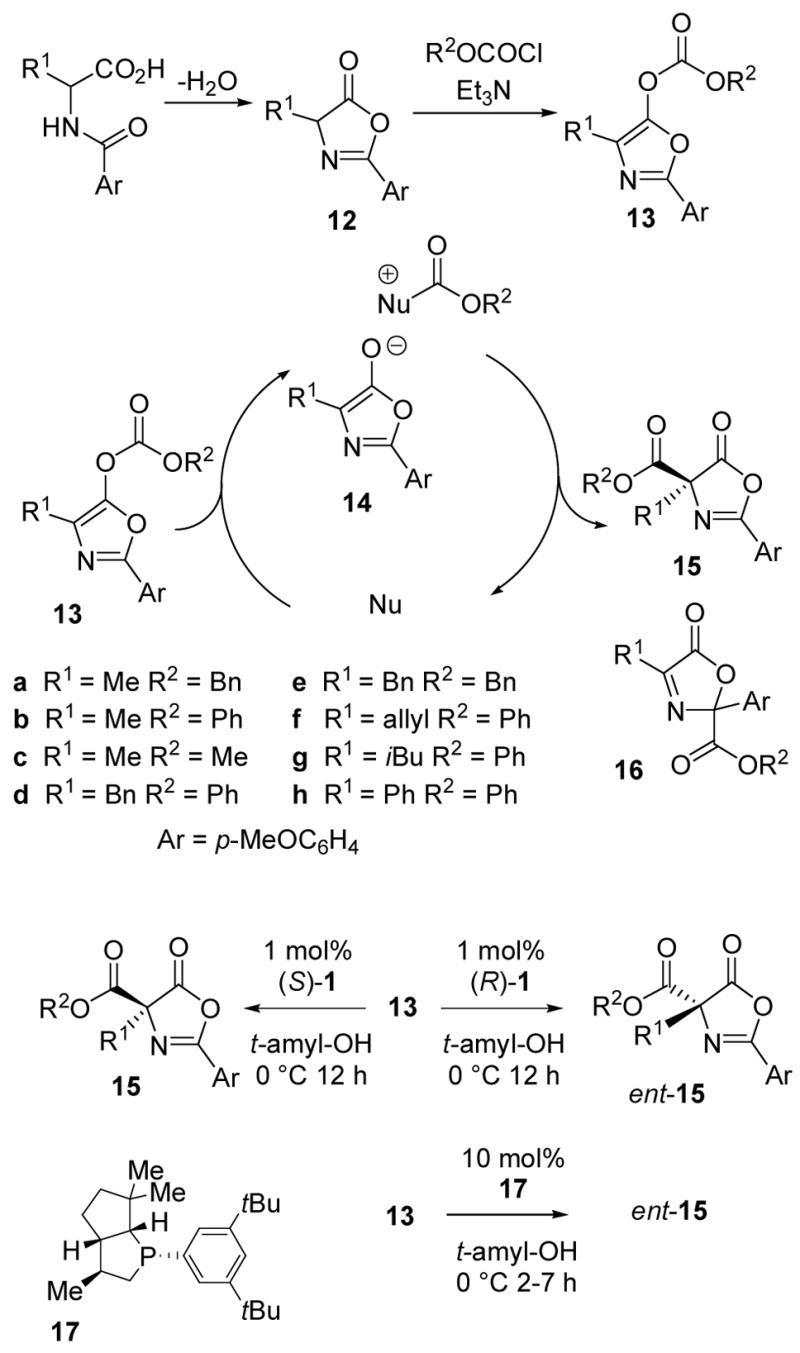

Enantioselective Steglich Rearrangement of Oxazolyl carbonates

The Steglich rearrangement (Scheme 2)22,23 was selected for a systematic investigation of carboxyl migration using catalyst 1. Oxazolyl carbonates 13 are easily synthesized from N-aroylamino acids via azlactones 12, and treatment with DMAP as a nucleophilic catalyst results in generation of an ion pair 14 followed by carboxyl migration to give the C-carboxyl azlactone 15. The rearrangement is high yielding if Ar= p-MeOC6H4, but the corresponding reaction with Ar= Ph affords a significant amount of the undesired C-2 carboxylated isomer 16.22 Fu and Ruble have reported a highly enantioselective version of the Steglich rearrangement of 13 (R2= Bn) using a planar-chiral pyridine catalyst.23 Comparisons with their results were expected to provide a basis for evaluating 1 as a chiral nucleophilic catalyst for synthesis of chiral quaternary carbon-containing molecules.24

Scheme 2.

Steglich Rearrangement.

In the initial experiments, the alanine-derived oxazolyl carbonate 13a23 was treated with 1 mol% of (S)-TADMAP (1) in CH2Cl2 (Table 2). The rearranged C-carboxylated isomer 15a was obtained in high yield as the only product, but the ee value was only 30%. Similar results were obtained with a methoxycarbonyl analog 13c in preliminary screens. However, changing the migrating group to phenoxycarbonyl (13b, R = Ph) and lowering the temperature to 0 °C gave a dramatic increase in selectivity, and afforded the C-carboxyl product 15b with 73% ee. Further improvement to 84–89% ee was observed in toluene or in ether solvents, and the best result was obtained in t-amyl alcohol (91% ee). Decomposition was noted in more polar solvents such as acetonitrile, so t-amyl alcohol was used in subsequent experiments to define the scope of the carboxyl migration.

Table 2.

3-Alkylbenzofuran enol carbonate rearrangements

| Entry | Substrate | Solvent | Yield (%) | ee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41a | CH2Cl2 | NA | 44 |

| 2 | 41b | CH2Cl2 | 97 | 71 |

| 3 | 41b | THF | 97 | 87 |

| 4 | 41b | Et2O | 92 | 92 |

| 5 | 41b | toluene | 89 | 89 |

| 6 | 41b | t-amyl-OH | NA | 70 |

| 7 | 41c | Et2O | 88 | 92 |

| 8 | 41d | Et2O | 96 | 93 |

| 9 | 41e | Et2O | 97 | 93 |

reaction at rt, 4h

A variety of substituted oxazolyl carbonates 13 were treated with 1 mol% of the enantiomeric TADMAP catalyst (R)-1 using the optimized t-amyl alcohol conditions. Excellent yields (90–99%) and enantiomeric excess (91–95% ee) were observed for all of the phenoxycarbonyl substrates 13b, d, f, g bearing an unbranched methylene sidechain. However, the benzyloxycarbonyl derivative 13e gave lower ee (ent-15e, 71% ee), similar to the behavior of 13a. Lower enantioselectivity was also observed with the phenyl glycine-derived 13h to afford the C-carboxylated azlactone product ent-15h (58% ee). Furthermore, the corresponding isopropyl substituted oxazolyl carbonate derived from valine gave no migration product at all, apparently due to excessive steric hindrance. These findings underscore the importance of substrates 13 having unbranched alkyl substituents R1 for the enantioselective Steglich rearrangement to 15 or ent-15 as well as the critical role of the phenoxycarbonyl migrating group.

The optimized enantioselectivities are comparable to those reported by Fu and Ruble, although their best results were obtained with the benzyloxycarbonyl migrating group, as in 13a and 13e.23 We were curious to know whether the migrating group would be subject to similar restrictions when the conversion from 13 to 15 is induced by the structurally unique, highly nucleophilic chiral phosphine 17,16b,f so the corresponding carboxyl migration experiments were investigated. Surprisingly, the carboxyl group was unimportant in this system, and nearly identical enantioselectivities in the range of 85–92% ee were observed for benzyloxy-, phenoxy-, and methoxycarbonyl substrates 13a, b, c (see Table S-3, Supporting Information for tabulated results). However, the phosphine catalyst 17 proved to be substantially less reactive than TADMAP (1), and efficient substrate conversion required ca. 10 mol% of the catalyst.

The identity of azlactone ent-15a obtained from 13a using 17 was established by comparing NMR data and the sign of optical rotation with known material.23 A chemical correlation was then performed to define the configuration of 15b (prepared from 13b and catalyst (S)-1) by ring opening with benzyl alcohol, or the corresponding ring opening of ent-15a with phenol. Both reactions were conducted under nucleophilic catalysis conditions (tributylphosphine/benzoic acid), and both gave the same enantiomer of an amido-malonate diester via alcoholysis of the azlactone (see Supporting Information for details).

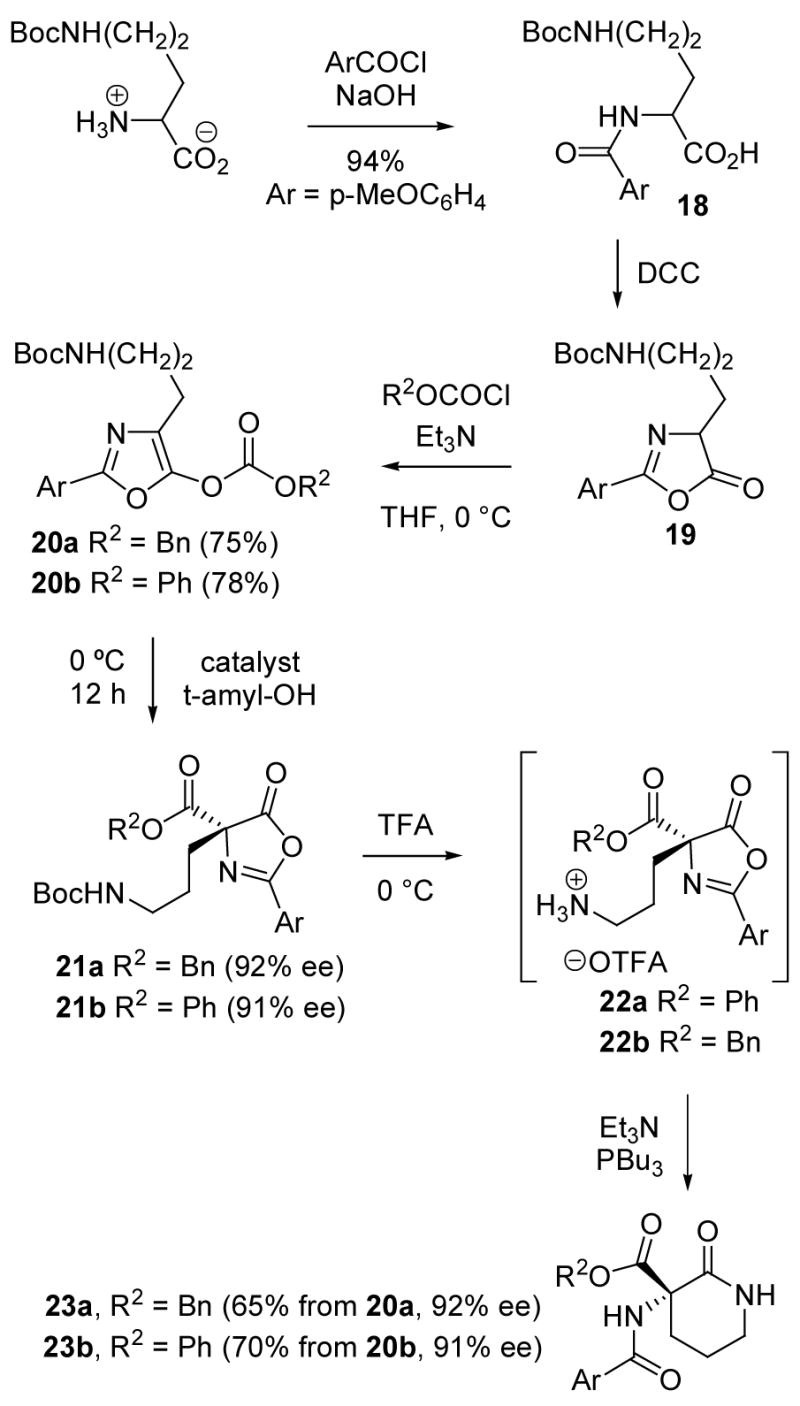

Based on the enantioselective carboxyl migrations briefly summarized above, good results were expected with oxazole substrates containing additional functionality designed to allow intramolecular bond formation following the carboxyl rearrangement step. Thus, the protected ornithine 18 was converted into the oxazole carbonates 20a and 20b via the azlactone 19 (Scheme 3). In accordance with the precedents, the benzyloxycarbonyl derivative 20a rearranged to 21a with good enantioselectivity (92% ee) upon treatment with 10 mol% of the chiral phosphine 17. Alternatively, the phenoxycarbonyl analog 20b gave 21b in 91% ee when 1 mol% of (R)-1 was used as the catalyst.

Scheme 3.

Deprotection of either of the oxazolyl carbonates 21a or 21b with trifluoroacetic acid followed by treatment of the intermediate salts 22a, b with Et3N/Bu3P to neutralize the salt and to catalyze nucleophilic azlactone cleavage afforded the lactams 23a or 23b (65–70% overall). In the case of 22b, replacing the nucleophilic Bu3P catalyst with the more basic DMAP or using excess Et3N without an added nucleophile gave a byproduct, apparently resulting from phenoxy displacement by the sidechain amine.25 This side-reaction was not observed from 22a because the benzyloxycarbonyl subunit is less activated compared to phenoxycarbonyl, but the same conditions for lactam formation were used as a precautionary measure. Lactams 23a and 23b were isolated with 92% ee and 91% ee, respectively, evidence that intermediates in the carboxyl migration retain the absolute configuration of the precursors 22a, b and do not undergo interconversion of the ester and azlactone carboxyl groups during conversion to 23.

In a similar sequence (Scheme 4), the protected homoserine 24 was N-aroylated, saponified to the carboxylic acid 25, and cyclized to the azlactone 26 by treatment with DCC. Subsequent conversion into the oxazolyl carbonates 27a or 27b was carried out in the usual way, and carboxyl migration was effected using 10 mol% of the phosphine catalyst 17 with 27a or 1 mol% of (R)-1 with 27b. The carboxyl migration products 28a (89% ee) and 28b (91% ee) were obtained in excellent yield and good enantiomeric purity. Subsequent silyl ether cleavage by treatment with HF·pyridine resulted in the direct conversion to the lactones 30a and 30b in >85% yield. The intermediate alcohols 29a, b were not detected in this case, and no additional catalysts were required for azlactone cleavage. However, use of the acidic fluoride source was critical as treatment of either 28a or 28b with the more basic TBAF reagent led to the formation of the α-amido lactone 31. Presumably, this occurs via a retro-Claisen/cyclization sequence, but the mechanistic details were not investigated. In any event, the results of Schemes 3 and 4 suggest a number of potential applications of the enantioselective carboxyl migration methodology for synthesis of unusual amino acid derivatives containing stereogenic quaternary carbon.26

Scheme 4.

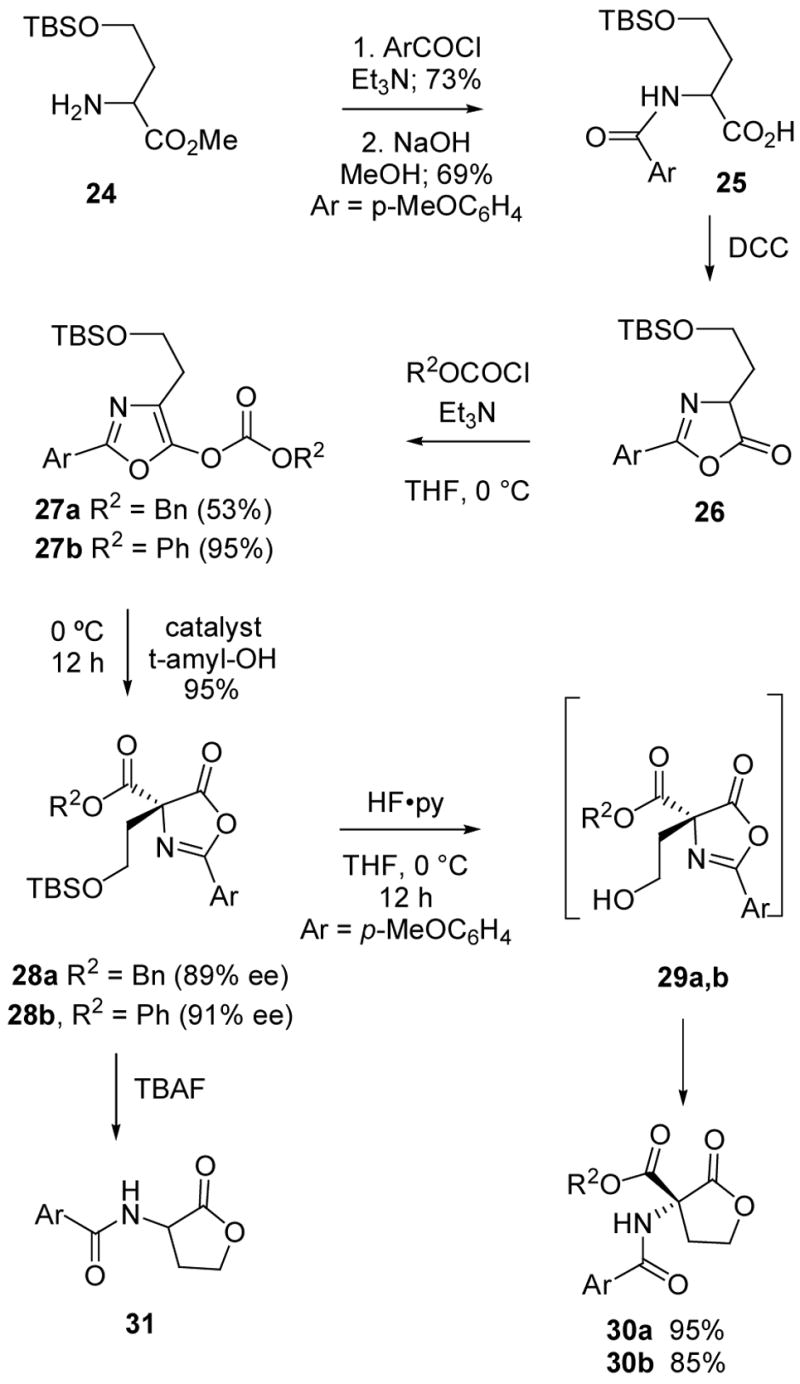

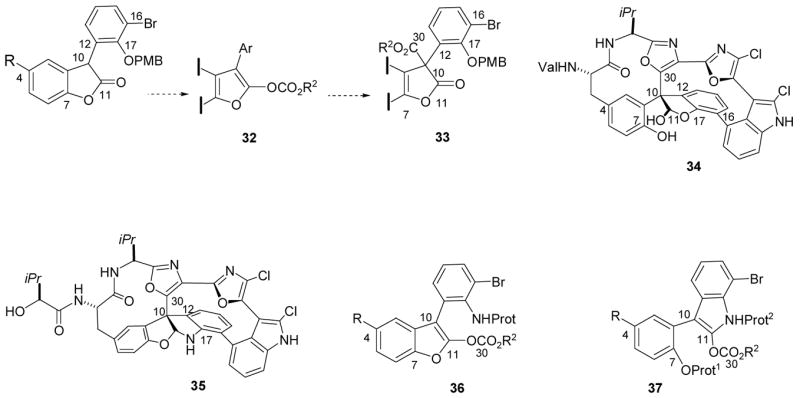

Enantioselective Carboxyl Migration of Furan-derived Enol Carbonates

Among the early goals of this program was to establish a route to chiral quaternary carbon-containing intermediates of the general structure 33 as part of our effort to obtain diazonamide A by total synthesis. An approach based on the Black rearrangement from a benzofuran 32 was therefore initiated (Scheme 5),27,28 but using chiral nucleophiles in place of Black’s DMAP catalyst. The mechanism of this reaction is believed to be closely analogous to that of the Steglich rearrangement discussed earlier. However, the original structure of the diazonamide A core (34) proved to be wrong, and a revised structure 35 has now been defined.29 In principle, 35 might also be accessed via Black rearrangement from a benzofuran substrate 36, or from the analogous rearrangement of an indole 37. Although strategic considerations eventually resulted in a different solution for the diazonamide quaternary carbon problem,30 the relevant benzofuran and indole rearrangements have been explored in depth in our laboratory, as described below. Similar substrates have been studied by Fu and Hills using their chiral DMAP catalyst with excellent results.31

Scheme 5.

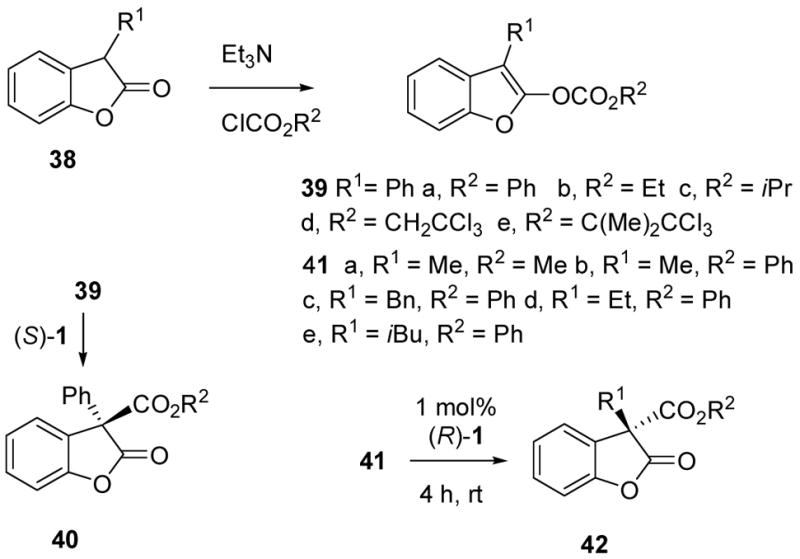

Simple benzofuranyl enol carbonates 39 and 41 were easily obtained from the known benzofuranones 38 (Scheme 6),32,33 but the enantioselective carboxyl rearrangement of 3-phenyl derivative 39 as a model for the hypothetical conversions from 32 to 33 proved to be a challenging problem. Treatment of the phenoxycarbonyl derivative 39a27 with 1 mol% of (S)-TADMAP (1) produced the C-carboxylated product 40a at room temperature, but the reaction was non-selective (2 % ee). A variety of other enol carbonates 39b–e were prepared and the carboxyl migrations were screened using (S)-1. The ethoxycarbonyl migrating group (39b) gave 40b with modest 26–44% ee in a variety of solvents at rt, while the iso-propoxycarbonyl derivative 39c gave totally racemic 40c. Only a small improvement was observed for the conversion of 39b to 40b at −20 °C (52–59% ee in ether, THF, or toluene). Fortunately, a larger temperature effect was found for 39d, and 40d was obtained in 86% ee and 92% yield by carrying out the reaction at −40 °C in dichloromethane. However, improved ee came at the cost of a significant rate decrease that required the use of 20 mol% of (S)-TADMAP (1) over 18 h. If desired, 95% of the TADMAP catalyst could be recovered via chromatography, but the high catalyst loading and long reaction time raised concerns about potential applications to more hindered substrates such as 32 or 36. Reactivity problems were also encountered in preliminary attempts to use chiral phosphine catalysts for the carboxyl rearrangement from 39 or analogs.34

Scheme 6.

After the struggle to optimize the rearrangement from 39 to 40, it was gratifying to find that the enantioselective carboxyl migration from the 3-alkyl benzofuranyl carbonates 41 to benzofuranones 42 is quite easy and follows the substrate preferences observed earlier with the oxazole substrates. This study was conducted using the enantiomeric TADMAP catalyst (R)-1, and began with a comparison of the methoxycarbonyl (41a) and phenoxycarbonyl (41b) migrating groups in dichloromethane. As with the oxazole substrates, the reaction was more highly selective with the phenoxycarbonyl migrating group (Table 2, entries 1 vs. 2), although the best ee’s were obtained in ether (entry 4) rather than tert-amyl alcohol (entry 6). Several other 3-alkyl benzofuranyl carbonates were investigated (entries 7–9) under the same conditions (ether, room temperature, 1 mol% of (R)-1) and afforded the desired C-phenoxycarbonyl benzofuranones 42c–e in good yield (88–97%) and enantiomeric excess (92–93% ee). The absolute stereochemistry of the C-carboxylated isomers 42b–e was assigned based on analogy with the oxazole studies, and with furanone derivatives to be discussed in the next section.

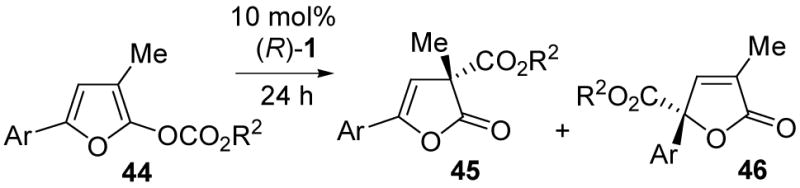

The TADMAP-catalyzed carboxyl migration reaction was extended to monocyclic furanone-derived enol carbonates 44. Treatment of the benzyloxy or phenoxy derivatives 44a or 44b with 1 mol% of TADMAP 1 led to the formation of two regioisomeric C-alkoxycarbonyl products 45a and 46a or 45b and 46b, respectively (Table 3, entries 1–2; 3:2 45:46). However, as observed earlier in the azlactone series, the phenoxycarbonyl group migrated with higher enantioselectivity (entry 2; 91% ee for 45b), so the phenoxy derivatives were explored in greater depth.

Table 3.

3-Methyl-5-arylfuran enol carbonate rearrangement

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Solvent | 45:46 a | eemajor (%) |

| 1b | 44a | CH2Cl2 | 3 : 2 | 75 |

| 2b | 44b | CH2Cl2 | 3 : 2 | 91 |

| 3 | 44c | CH2Cl2 | 5 : 1 | 82 |

| 4 | 44c | THF | 10 : 1 | 90c |

| 5 | 44c | Et2O | 11 : 1 | 83 |

| 6 | 44c | toluene | 10 : 1 | 74 |

| 7 | 44c | t-amyl-OH | 6 : 1 | 91 |

| 8d | 44d | CH2Cl2 | 1 : 4 | 63 |

| 9d | 44d | THF | 1 : 4 | 74 |

| 10d | 44d | Et2O | 1 : 4 | 90e |

| 11d | 44d | toluene | 1 : 4 | 83 |

| 12d | 44d | t-amyl-OH | 1 : 4 | 50 |

ratio based on NMR assay, >95% conversion

1 mol% of catalyst 1

45: 83% yield 45; 46: 7% yield (80% ee)

reaction complete in 4 h

46: 75% yield; 45: 25% yield

In an attempt to improve regiocontrol, the electronic effect of the C-5 aryl substituent was varied. The relatively electron rich methoxyphenyl derivative 44c produced a better ratio (up to 11:1) favoring the α-carboxyl isomer 45c (Table 3, entries 3–7). However, the electron deficient 44d gave a reversed 4:1 ratio favoring the γ-carboxyl product 46d (entries 8–12). After optimization of solvent for each substrate, good yields and ee values were obtained for the major product in each example. The striking electronic effect of donor or acceptor substituents at C-5 aryl in these reactions is reminiscent of the trends reported by Steglich and Höfle for the related oxazole rearrangements, as already mentioned in connection with Scheme 2.22

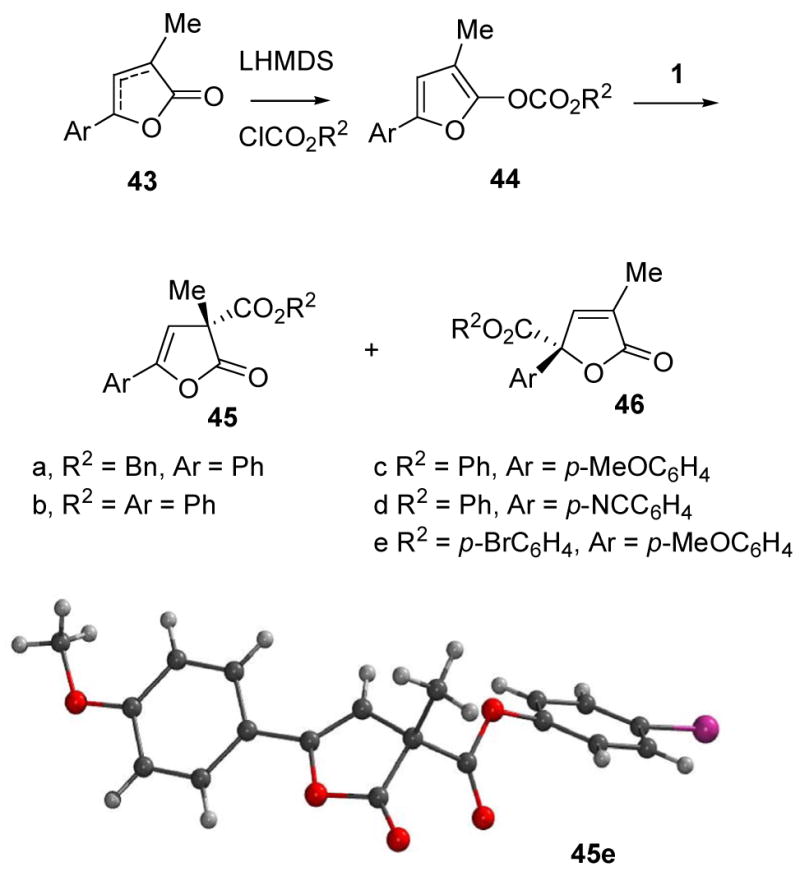

The absolute stereochemistry of the furanones was probed in the case of the p-bromophenyl furanone 45e (Scheme 7), obtained in the usual way (88% ee, 75% yield from 44, using (R)-1), along with a small amount of isomer 46e. After crystallization, the major product 45e was analyzed by X-ray crystallography (anomalous dispersion) and was shown to possess the (R)-45e absolute stereochemistry. The absolute configurations of other furanone carboxyl migration products were assigned by analogy. This stereochemistry is similar to that observed for the corresponding methyl substituted azlactone 15b, as expected given the structural similarities.

Scheme 7.

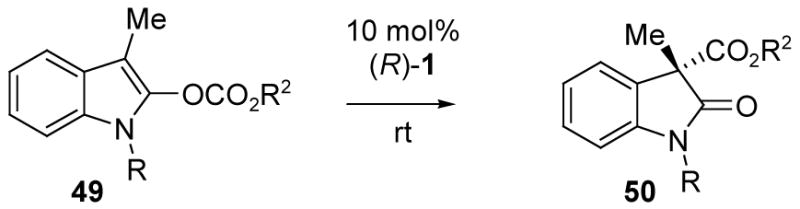

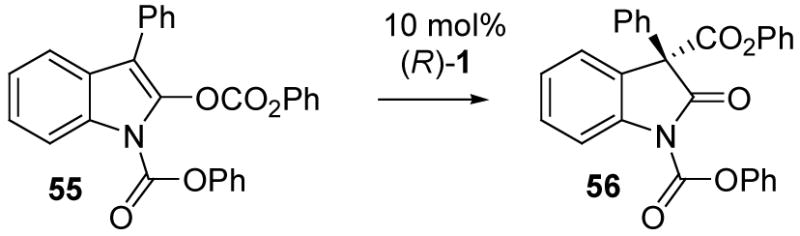

Enantioselective carboxyl migration of 3-substituted 2-alkoxycarbonyloxyindoles

Extension of the carboxyl migration methodology to 2-indolyl enol carbonates proved difficult and somewhat problematic. Treatment of 49a with 10 mol% of TADMAP 1 afforded the desired 50 as the sole product (Table 4, entries 1–5). However, the reaction was very slow, requiring over a month to reach completion at room temperature. While the enantioselectivity was in the promising range in the best solvents, (45–55% ee), ee improvement at lower temperatures was not an option due to poor reactivity. Evidently, the enolate subunit of the necessary ion pair intermediate 51 is not sufficiently stabilized, an effect that can be attributed to the substituent at indole nitrogen, R= N-CO2Ph. Although the inductive effect of amide carbonyl is expected to help stabilize a simple enolate,35 there is an opposing factor in 51 because the nitrogen electron pair is potentially part of a delocalized indole π-system while amide delocalization with R= N-CO2Ph works against aromaticity. According to this rationale, substrates 49b–e containing relatively electron rich R= allyl, benzyl, p-methoxyphenyl, methyl at indole nitrogen may be more reactive due to increased stability for 51.

Table 4.

3-Alkylindole enol carbonate rearrangement

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Solvent | Timea | ee (%) |

| 1 | 49a | CH2Cl2 | 35 d | 23 |

| 2 | 49a | THF | 35 d | 55 |

| 3 | 49a | Et2O | 35 d | 55 |

| 4 | 49a | toluene | 35 d | 45 |

| 5 | 49a | t-amyl-OH | 35 d | 33 |

| 6 | 49b | CH2Cl2 | 8 d | 37 |

| 7 | 49b | THF | 8 d | 2 |

| 8 | 49c | CH2Cl2 | 8 d | 7 |

| 9 | 49c | THF | 8 d | 18 |

| 10 | 49d | CH2Cl2 | 28 d | 48 |

| 11 | 49d | THF | 28 d | 50 |

| 12 | 49e | CH2Cl2 | 24 h | 2 |

| 13 | 49e | THF | 24 h | 23 |

| 14 | 49f | CH2Cl2 | 24 h | <1 |

| 15 | 49f | THF | 24 h | <1 |

| 16 | 49g | CH2Cl2 | 24 h | 10 |

| 17 | 49g | THF | 24 h | 5 |

| 18 | 49h | CH2Cl2 | 24 h | 39 |

| 19 | 49h | t-amyl-OH | 24h | 49 |

| 20 | 53 | CH2Cl2 | 3 h | 65 |

| 21 | 53 | THF | 5 h | 61 |

| 22 | 53 | CH2Cl2 | 24 h | 75b |

| 23 | 53 | t-amyl-OH | 5 h | 44 |

| 24 | 53 | t-amyl-OH | 24 h | 78b |

time required for >95% conversion of 49 or 53

reaction at 0 °C; >98% yield

Enol carbonates 49b–e were screened, and improved reactivity was indeed observed (entries 6–13). However, the enantioselectivities were marginal at best, and poor for the most highly reactive N-methyl indole 49e. In an attempt to address this problem, optimization of the migrating group was investigated (entries 14–18). The best result was obtained with 49h (trichlorobutoxycarbonyl as the migrating group, 49% ee). No attempt was made to correlate absolute configuration in view of the modest ee values, so the configurations as drawn are tentative, and are based on the furan and oxazole analogies.

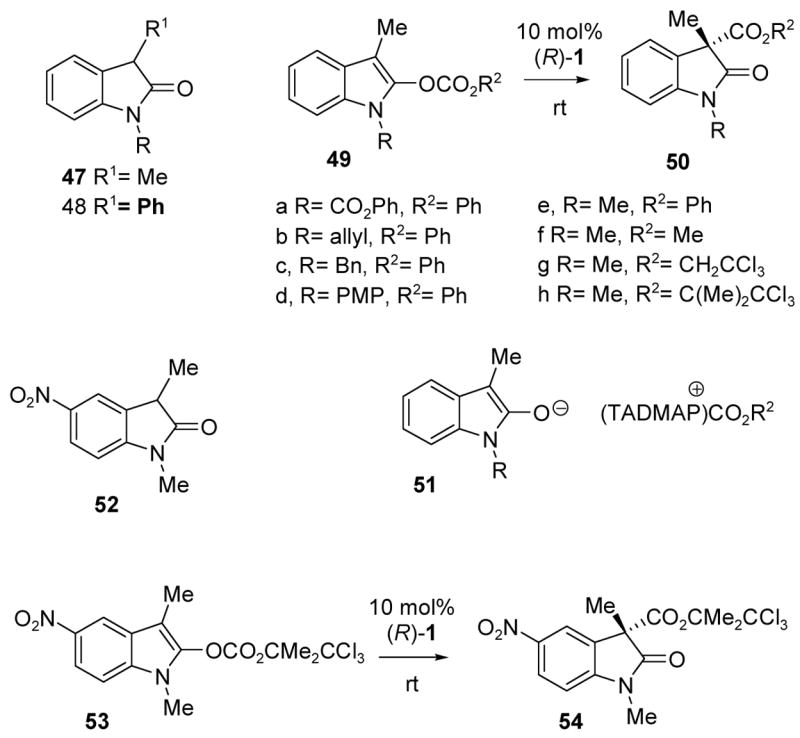

To provide greater flexibility for optimization in the indole series at low temperatures, the substrate was modified by the introduction of an electron-withdrawing nitro group to help stabilize the intermediate ion pair (Scheme 8). The starting nitrooxindole 52 was prepared by oxidation of the corresponding indole,36 and was converted into enol carbonate 53. Compared to the analogous 49h, the carboxyl migration rate upon treatment with 10 mol% of the catalyst 1 increased by ca. 8-fold at room temperature. Additionally, the selectivity improved substantially (entries 20–21), and could be further enhanced by lowering the temperature to 0 °C (entries 22 and 24), leading to the functionalized C-carboxylated oxindole 54 in 75–78% ee, >98% yield.

Scheme 8.

In a final series of experiments, the carboxyl migration methodology was extended to the N-protected 3-phenylindole 55 as a model substrate corresponding to 37, the indole precursor that would be needed in a carboxyl migration approach to diazonamide A as discussed in connection with Scheme 6. Enol carbonate 55 was obtained in 87% yield by reaction of 3-phenyloxindole with phenyl chloroformate and triethylamine. Subsequent treatment of 55 with 10 mol% TADMAP, (R)-1, produced the desired carboxyl migration product 56. The enantioselectivity in various solvents was good to excellent (Table 5), but the reaction was slow compared to the N-alkyl-3-methylindole examples of Table 4 (entries 12–18). Reactivity was improved for 55 compared to the N-phenoxycarbonyl-3-methyl analog 49a, probably due to the stabilizing effect of the 3-phenyl substituent at the stage of the ion pair intermediate, but several days or more were required for conversion of 55 at room temperature. Fortunately, the reaction could be conducted at 35–40 °C with only modest erosion of the enantiomeric excess (Table 5, entries 3, 5, 7, 9), resulting in good conversion within 18 hours. In the best case (entry 9), using t-amyl alcohol as the solvent, the desired oxindole 56 was formed in 93% yield and 86% ee.

Table 5.

3-Phenylindole enol carbonate rearrangement

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solvent | Temp. (°C) | Timea (h) | ee (%) |

| 1 | CH2Cl2 | 23 | 96 | 73 |

| 2 | THF | 23 | 96 | 82 |

| 3 | THF | 40 | 18 | 82 |

| 4 | Et2O | 23 | 96 | 90 |

| 5 | Et2O | 35 | 18 | 83 |

| 6 | toluene | 23 | 96 | 87 |

| 7 | toluene | 40 | 18 | 74 |

| 8 | t-amyl-OH | 23 | 96 | 90 |

| 9 | t-amyl-OH | 40 | 18 | 86b |

time required for >95% conversion of 55

93% isolated yield

Compared to the relatively facile, highly enantioselective phenoxycarbonyl migrations with oxazole, furan, and benzofuran substrates, the analogous indole enol carbonates are substantially less reactive, and the enantioselectivity trends in Tables 4–5 are somewhat different. Much of the reactivity difference probably reflects the decreased stability of ion pair 51 compared to analogous intermediates in the oxazole, furan, and benzofuran series. Qualitatively, this difference can be appreciated by comparing the pKa values of the unsubstituted benzofuranone 38 with R1= H (pKa = 11.9) and the corresponding N-methyloxindole, 47 with R1= H (pKa= 15.7),37 adjusted for the added delocalization by R1= Ph (pKa 8.4 for 38 with R1= Ph).38

Assuming that the enantioselectivity-determining transition states for product formation in the more facile oxazole and furan enol carbonate rearrangements resemble tetrahedral intermediates leading to the C-carboxylated products, two isomeric transition structures 57 or 58 can be considered for substrates where R1 has a methylene group connected to the ring (Fig. 4). Structure 57 would be formed from the less hindered phenoxycarbonyl pyridinium salt conformer, and should be favored since it would also have fewer interactions between the phenoxy and trityl groups. As drawn, these structures somewhat exaggerate the role of one of the trityl phenyl groups in blocking the lower face of the pyridine ring,39 but preferred bonding from the top face is expected. Analogous structures are plausible in the most highly enantioselective oxazole (59), furan (60), and benzofuran (61) rearrangements, provided that Ra corresponds to the eventual carbonyl group in the product, Rb is the unbranched carbon substituent required for optimum ee, and Rc is the aromatic substituent (C2 aryl in 59; C5 aryl in 60; benzo-fused ring in 61). In these examples, the favored conformer is relatively devoid of unfavorable steric interactions, and the qualitative models correspond to the sense of enantioselectivity. However, the analogous indole structure (62) would project the N-R substituent toward the acetoxy group of the catalyst. The added steric requirements of the indole N-R group may contribute to the decreased reactivity of 49a–d as well as to the low enantioselectivity observed with 49e. Thus, the faster rearrangements are observed with the smallest N-R group (Me > allyl or benzyl, Table 4, entry 12 vs. entries 6, 8). However, there is no simple correlation of reactivity with enantioselectivity in Table 4. The qualitative model sheds no light on the preferred geometry for the indole rearrangements, and does not address the detailed differences among the alkoxycarbonyl migrating groups.

Figure 4.

Qualitative models for stereochemical induction.

Summary

TADMAP (1) has been shown to catalyze the carboxyl migration of oxazolyl, furanyl, and benzofuranyl enol carbonates with good to excellent levels of enantioselection. In general these findings compare well in terms of yield, reactivity, and catalyst loading to the results reported earlier by Fu et al. using their planar chiral catalyst for similar rearrangements,23,31 although the enantioselectivities are somewhat lower for the benzofuran and indole substrates. The oxazole reactions are especially efficient, and applications in more highly functionalized substrates allow the synthesis of convenient precursors of chiral lactams and lactones containing a quaternary asymmetric carbon. The analogous TADMAP-catalyzed indole reactions suffer from inconsistent enantioselectivity and low reactivity requiring the use of 10 mol% of catalyst. Better enantioselection was observed by Fu et al. for the indoles, although a similar reactivity problem was encountered. Further studies will be needed to improve reactivity as well as catalyst accessibility. Even with the relatively short synthesis, TADMAP is probably not suitable for applications where 10% catalyst loading is necessary. However, shorter routes to analogous 3-substituted DMAP derivatives are easily imagined, and relevant studies are under way.

As a final comment, we will briefly note that TADMAP is only modestly selective as a catalyst for kinetic resolution. In a preliminary study, the best enantioselectivity s= 4.4 was observed for the iso-butyroylation of 1-naphthyl-1-ethanol at room temperature. If kinetic resolution had been used as the exclusive probe for the potential utility of TADMAP as a chiral nucleophilic catalyst, we may have opted to explore new catalysts and to bypass the experiments leading to the highly enantioselective carboxyl migrations reported above.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures, characterization and crystal structures (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (CA17918), and by fellowships provided to S.A.S. by the University of Michigan, Board of Regents, and to P.A. by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Culture.

References

- 1.For reviews on asymmetric nucleophilic catalysis: Spivey AC, Maddaford A. Org Prep Proced Int. 2000;32:333.Spivey AC, Andrews BI. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:3131. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010216)40:4<769::aid-anie7690>3.0.co;2-5.Dalko PI, Moisan L. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2001;49:3726. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011015)40:20<3726::aid-anie3726>3.0.co;2-d.Jarvo ER, Miller SJ. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:2481.Taggi AE, Hafez AM, Lectka T. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:10. doi: 10.1021/ar020137p.France S, Guerin DJ, Miller SJ, Lectka T. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2985. doi: 10.1021/cr020061a.Dalko PI, Moisan L. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:5138. doi: 10.1002/anie.200400650.

- 2.For general reviews on nucleophilic organocatalysis: Höfle G, Steglich W, Vorbruggen H. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1978;17:569.Scriven EFV. Chem Soc Rev. 1983;12:129.Lu X, Zhang C, Xu Z. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:535. doi: 10.1021/ar000253x.Murugan R, Scriven EFV. Aldrichimica Acta. 2003;36:21.Basavaiah D, Rao AJ, Satyanarayana T. Chem Rev. 2003;103:811. doi: 10.1021/cr010043d.Methot JL, Roush WR. Adv Syn Catal. 2004;346:1035.Spivey AC, Arseniyadis S. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:5436. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460373.

- 3.(a) Wegler R. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1932;498:62. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wegler R. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1933;506:77. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wegler R. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1934;510:72. [Google Scholar]; (d) Wegler W, Rüber A. Chem Ber. 1935;68:1055. [Google Scholar]; (e) Bird CW. Tetrahedron. 1962;18:1. [Google Scholar]; (f) Stegmann W, Uebelhart P, Heimgartner H, Schmid H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:3091. [Google Scholar]; (g) Potapov VM, Dem’yanovich VM, Khlebnikov VA, Korovina TG. Zh Org Khim. 1988;24:759. and references therein. [Google Scholar]; (h) Weidert PJ, Geyer E, Horner L. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1989:533. [Google Scholar]; (i) Oriyama T, Hori Y, Imai K, Sasaki R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8543. [Google Scholar]; (j) Sano T, Imai K, Ohashi K, Oriyama T. Chem Lett. 1999:265. [Google Scholar]; (k) Sano T, Miyata H, Oriyama T. Enantiomer. 2000;5:119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Vedejs E, Chen X. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:1809. [Google Scholar]; (b) Harper LA. Studies Toward an Enantioselective Nucleophilic Catalyst Based on Dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) Chem Abs. 2001;136:369315. [Google Scholar]; (c) Shaw SA, Aleman P, Vedejs E. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13368. doi: 10.1021/ja037223k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Ruble JC, Fu GC. J Org Chem. 1996;61:7230. doi: 10.1021/jo961433g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fu GC. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:412. doi: 10.1021/ar990077w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fu GC. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:542. doi: 10.1021/ar030051b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Kawabata T, Nagato M, Takasu K, Fuji K. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:3169. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kawabata T, Yamamoto K, Momose Y, Yoshida H, Nagaoka Y, Fuji K. Chem Commun. 2001:2700. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kawabata T, Stragies R, Fukaya T, Fuji K. Chirality. 2003;15:71. doi: 10.1002/chir.10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kawabata T, Stragies R, Fukaya T, Nagaoka Y, Schedel H, Fuji K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:1545. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Spivey AC, Fekner T, Spey SE. J Org Chem. 2000;65:3154. doi: 10.1021/jo0000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Spivey AC, Maddaford A, Fekner T, Redgrave AJ, Frampton CS. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 2000:3460. [Google Scholar]; (c) Spivey AC, Zhu F, Mitchell MB, Davey SG, Jarvest RL. J Org Chem. 2003;68:7379. doi: 10.1021/jo034603f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Spivey AC, Leese DP, Zhu F, Davey SG, Jarvest RL. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:4513. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Priem G, Anson MS, Macdonald SJF, Pelotier B, Campbell IB. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:6001. [Google Scholar]; (b) Priem G, Pelotier B, Macdonald SJF, Anson MS, Campbell IB. J Org Chem. 2003;68:3844. doi: 10.1021/jo026485m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pelotier B, Priem G, Campbell IB, Macdonald SJF, Anson MS. Synlett. 2003:679. doi: 10.1021/jo026485m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.K-S, Kim S-H, Park H-J, Chang K-J, Kim KS. Chem Lett. 2002:1114. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabanella S, Valancogne I, Jackson RFW. Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:4254. doi: 10.1039/b308750f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Miller SJ, Copeland GT, Papaioannou N, Horstmann TE, Ruel EM. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:1629. [Google Scholar]; (b) Copeland GT, Jarvo ER, Miller SJ. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6784. doi: 10.1021/jo981642w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Copeland GT, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4306. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jarvo ER, Copeland GT, Papioannou N, Bonitatebus PJ, Jr, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11638. [Google Scholar]; (e) Harris RF, Nation AJ, Copeland GT, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:11270. [Google Scholar]; (f) Jarvo ER, Vasbinder MM, Miller SJ. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:9773. [Google Scholar]; (g) Copeland GT, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6496. doi: 10.1021/ja0108584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Vasbinder MM, Jarvo ER, Miller SJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:2824. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010803)40:15<2824::aid-anie2824>3.3.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Jarvo ER, Evans CA, Copeland GT, Miller SJ. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5522. doi: 10.1021/jo015803z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Papaioannou N, Evans CA, Blank JT, Miller SJ. Org Lett. 2001;3:2879. doi: 10.1021/ol016372+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Fierman MB, O’Leary DJ, Steinmetz WE, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6967. doi: 10.1021/ja049661c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishihara K, Kosugi Y, Akakura M. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12212. doi: 10.1021/ja045850j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birman VB, Uffman EW, Jiang H, Li X, Kilbane CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12226. doi: 10.1021/ja0491477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kano T, Sasaki K, Maruoka K. Org Lett. 2005;7:1347. doi: 10.1021/ol050174r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan A, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2005;7:905. doi: 10.1021/ol050100f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Vedejs E, Daugulis O, Diver ST. J Org Chem. 1996;61:430. doi: 10.1021/jo951661v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vedejs E, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:5813. doi: 10.1021/ja021224f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Vedejs E, MacKay JA. Org Lett. 2001;3:535. doi: 10.1021/ol006923g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Vedejs E, Daugulis O, MacKay JA, Rozners E. Synlett. 2001:1499. [Google Scholar]; (e) Vedejs E, Rozners E. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2428. doi: 10.1021/ja0035405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Vedejs E, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4166. doi: 10.1021/ja021224f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Vedejs E, Daugulis O, Harper LA, MacKay JA, Powell DR. J Org Chem. 2003;68:5020. doi: 10.1021/jo030007+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassner A, Krepski LR, Alexanian V. Tetrahedron. 1978;34:2069. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis FA, Reddy RE, Szewczyk JM, Reddy GV, Portonovo PS, Zhang H, Fanelli D, Reddy RT, Zhou P, Carroll PJ. J Org Chem. 1997;62:2555. doi: 10.1021/jo970077e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groziak MP, Melcher LM. Heterocycles. 1987;26:2905. [Google Scholar]

- 20.pKaDMSO: Bordwell FG. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:456. pKaMeCN: (b) ChemFiles, Fluka, vol. 3

- 21.PC SPARTAN PRO, ver 1. Wavefunction, Inc; Irvine, CA: 1999. Wavefunction. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Steglich W, Höfle G. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1968;7:61. [Google Scholar]; (b) Steglich W, Höfle G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968;9:1619. [Google Scholar]; (c) Steglich W, Höfle G. Chem Ber. 1969;102:883. [Google Scholar]; (d) Steglich W, Höfle G. Chem Ber. 1969;102:899. [Google Scholar]; (e) Steglich W, Höfle G. Tetradedron Lett. 1970;11:4727. [Google Scholar]; (f) Steglich W, Höfle G. Chem Ber. 1971;104:3644. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruble JC, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11532. [Google Scholar]

- 24.For reviews on asymmetric quaternary carbon synthesis: Martin SF. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:419.Fuji K. Chem Rev. 1993;93:2037.Corey EJ, Guzman-Peres A. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1998;37:389. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980302)37:4<388::AID-ANIE388>3.0.CO;2-V.Christoffers J, Mann A. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:4591. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4591::aid-anie4591>3.0.co;2-v.Christoffers J, Baro A. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:1688. doi: 10.1002/anie.200201614.Denissova I, Barriault L. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:10105.

-

25.Structure i for the byproduct is consistent with NMR and IR data.

- 26.For reviews α,α-disubstituted amino acids, see Cativiela C, Diaz-de-Villegas MD. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1998;9:3517.Cativiela C, Diaz-de-Villegas MD. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2000;11:645.. For an alternative approach to α,α-disubstituted amino acids from azlactones, see Trost BM, Chulbom L. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12191. doi: 10.1021/ja0118338.

- 27.Black TH, Arrivo SM, Schumm JS, Knobeloch JM. J Org Chem. 1987;52:5425. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Wang J. Diss. Abs. Int., B. Vol. 59. Ph D Thesis, University of Wisconsin, 1997; 1997. 1998. Studies Toward the Asymmetric Synthesis of Diazonamide A; p. 1121. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vedejs E, Wang J. Org Lett. 2000;2:1031. doi: 10.1021/ol005547x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Li J, Burgett AWG, Esser L, Amezcua C, Harran PG. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:4770. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4770::aid-anie4770>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Bella M, Chen DYK, Huang XH, Ling TT, Snyder SA. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:3495. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3495::AID-ANIE3495>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nicolaou KC, Rao PB, Hao JL, Reddy MV, Rassias G, Huang XH, Chen DYK, Snyder SA. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:1753. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Burgett AWG, Li Q, Wei Q, Harran PG. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:4961. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peris, G.; Vedejs, E., to be published.

- 31.Hills ID, Fu GC. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:3921. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351666. A related acyl migration approach to saturated furanones is reported by Mermerian AH, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5604. doi: 10.1021/ja043832w.

- 32.38 with R1= Me, Piccolo O, Filippini L, Tinucci L, Valoti E, Attilio C. J Chem Res Synop. 1985:258.

- 33.38 with R1= misc. alkyls, Yoneda E, Sugioka T, Hirao K, Zhang SW, Takahashi S. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1998:477. R = Ph.Padwa A, Dehm D, Oine T, Lee GA. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:1837.

- 34.The rearrangement of 39b works very well using simple phosphine catalysts and is complete within 2h at rt with 1 equiv Et3P or Bu3P, or 24h using Et2PPh (see ref. 28, p. 149). A modestly enantioselective version of the rearrangement can be effected using the P-Ph analog of 16 (32% ee, 84–7% yield after 24h at rt with ca. 7% of the catalyst in CH2Cl2). However, attempts to achieve similar rearrangement with more highly substituted enol carbonates of general structure 32 resulted in low reactivity and formation of the parent benzofuranone as a sideproduct. This side-reaction, superficially corresponding to enolate protonation at the stage of the ion pair, was observed in nearly all attempts, and little Ccarboxylated product was obtained even with simple phosphines. The side-reaction was also dominant in the case where 10% Et3P was used to catalyze the rearrangement of 39b with Ph replaced by o-tolyl (Barda, D. A.; Vedejs, E., unpublished results).

- 35.Garst ME, Bonfiglio JN, Grudoski DA, Marks J. J Org Chem. 1980;45:2307. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takase S, Uchida I, Tanaka H, Aoki H. Tetrahedron. 1986;42:5879. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kresge AJ, Meng Q. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9189. doi: 10.1021/ja020367z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heathcote DM, De Boos GA, Atherton JH, Page MI. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 2. 1998:535. [Google Scholar]

- 39.A more more sterically demanding analog of TADMAP was prepared with the trityl group replaced by tris(3,5-dimethylphenyl)methyl. Virtually identical results were obtained using this catalyst in dichloromethane (rt) for the carboxyl migrations of 39b (28% ee) and 41b (73% ee) compared to TADMAP, while lower enantioselectivities were observed starting with 13a (12% ee) and 44b (79% ee).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures, characterization and crystal structures (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.