Possibly 10 years. The longest published follow-up extended five years, at which time antibody levels and cell-mediated immunity were still readily detectable (1). The slow antibody decay pattern suggests that protection will last for at least 10 years (2). However, antibody levels do not correlate well with protection against pertussis, so proof of ongoing protection will have to come from epi-demiological studies.

A major challenge for pertussis control is that neither natural infection nor immunization induce life-long immunity against subsequent infection.

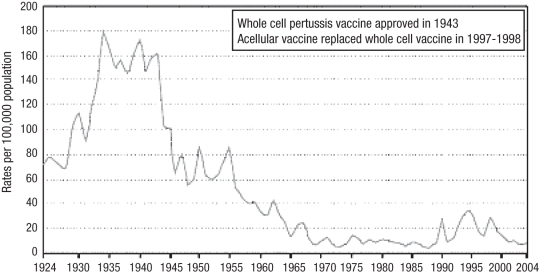

After the introduction of pertussis vaccine more than five decades ago, disease incidence decreased dramatically from 157 per 100,000 individuals in the prevaccine era to less than one per 100,000 individuals in the early 1970s, a decrease of more than 99%. The majority of remaining cases were noted in children younger than 10 years of age. Over the past two decades, a gradual increase in pertussis incidence has occurred (Figure 1), reaching 8.9 per 100,000 individuals per year in 2004, with the majority of cases now seen in adolescents and adults (1,2), who are the major source of infection for young infants (3). Fully immunized children older than six months of age are well protected by acellular vaccines. Young infants often have severe pertussis, and account for most related deaths (4). To improve disease control, all provinces and territories have expanded their pertussis immunization programs to include a booster dose for adolescents, namely the tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis (Tdap) vaccine. Two such products that contain reduced amounts of diphtheria and certain pertussis antigens to minimize side effects are currently approved for use in adolescents and adults. Adverse effects occur at approximately the same rates with Tdap, and combined tetanus-diphtheria vaccines.

Figure 1.

Incidence rate of pertussis infections in Canada between 1924 and 2004, based on notifications to Health Canada. Reproduced from reference 10

The mechanism of immunity to pertussis after natural infection or immunization is complex and not fully understood. Immunity has been shown to wane seven to 20 years after natural infection and five to 10 years after immunization with whole cell vaccines (5). Current acellular vaccines elicit antibodies to the key antigens of pertussis including pertussis toxin, pertactin (PRN), filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) and fimbriae, but the minimum serum antibody concentrations that protect against infection have not yet been determined. Cell-mediated immunity against pertussis is also elicited by immunization, but its role in protecting against infection is unclear (6,7). Edelman et al (7) recently reported persistence of immunoglobulin G antibodies against PRN and FHA, five years after Tdap booster vaccination of adolescents. They also demonstrated persistent cell-mediated immunity responses against pertussis toxin, PRN and FHA, consistent with ongoing immune memory. Thus, the authors predicted that adequate protection would extend beyond five years and probably to 10 years postimmunization (7). That means adolescent vaccinees may again become susceptible to pertussis as young adults and/or parents, and pose a risk for young infants. Developing strategies to extend protection among adults will be essential for maximal disease control. Implementing Tdap boosters every 10 years in adults is unlikely to be sufficient given the poor compliance with 10-yearly tetanus-diphtheria boosters. Innovative approaches are needed, such as targeting adults about to start a family or possibly boosting women during pregnancy (a subject of ongoing studies) (8). Recently, a group of pertussis researchers recommended a ‘cocooning’ strategy, which entails immunization of family members and close contacts of the newborn, aiming to create a protective environment for the most vulnerable infants where it is economically feasible (9).

Awareness about pertussis, its risks and the importance of vaccination needs to be emphasized to adolescents and adults, including health care workers and day care providers who care for children. Paediatricians should ensure that they and their office staff have set a good example.

The Upshots column in Paediatrics & Child Health is meant to address practical questions without ready answers in standard references such as the Red Book or the Canadian Immunization Guide. Readers are invited to submit questions to the journal office. A timely response will be provided, whenever possible, from one member of a panel of experts. The most interesting exchanges will be selected for publication. Submitters should identify themselves, but will be given the option of anonymity in the published version. Submitted questions may be edited for clarity and brevity.

David Scheifele MD

Associate Editor, Paediatrics & Child Health

REFERENCES

- 1.Cherry JD. Immunity to pertussis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1278–9. doi: 10.1086/514350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg DP. Pertussis in adolescents: Increasing incidence brings attention to the need for booster immunization of adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:721–8. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000172905.08606.a3. (Erratum in 2005;24:983) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendelboe AM, Njamkepo E, Bourillon A, et al. Transmission of Bordetella pertussis to young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:293–9. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000258699.64164.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mikelova LK, Halperin SA, Scheifele D, et al. Members of the Immunization Monitoring Program, ACTive (IMPACT) Predictors of death in infants hospitalized with pertussis: A case-control study of 16 pertussis deaths in Canada. J Pediatr. 2003;143:576–81. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00365-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wendleboe AM, Van Rie A, Salmaso S, Englund JA. Duration of immunity against pertussis after natural infection or vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(Suppl 5):S58–61. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000160914.59160.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran Minh NN, He Q, Edelman K, et al. Cell-mediated immune responses to antigens of Bordetella pertussis and protection against pertussis in school children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:366–70. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199904000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelman K, He Q, Mäkinen J, et al. Immunity to pertussis 5 years after booster immunization during adolescence. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1271–7. doi: 10.1086/514338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards KM, Halasa N. Are pertussis fatalities in infants on the rise? What can be done to prevent them? J Pediatr. 2003;143:552–3. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsyth KD, Wirsing von Konig CH, Tan T, Caro J, Plotkin S. Prevention of pertussis: Recommendations derived from the second Global Pertussis Initiative roundtable meeting. Vaccine. 2007;25:2634–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Public Health Agency of Canada. Pertussis. < http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/vpd-mev/pertussis_e.html> (Version current as November 23, 2007)