Abstract

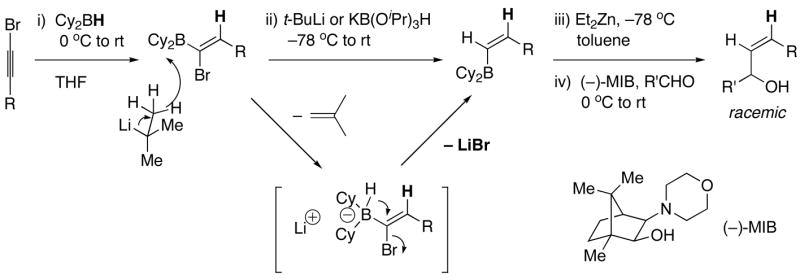

A one-pot method for the direct preparation of enantioenriched (Z)-disubstituted allylic alcohols is introduced. Hydroboration of 1-halo-1-alkynes with dicyclohexylborane, reaction with t-BuLi, and transmetallation with dialkylzinc reagents generates (Z)-disubstituted vinylzinc intermediates. In situ reaction of these reagents with aldehydes in the presence of a catalyst derived from (−)-MIB generates (Z)-disubstituted allylic alcohols. It was found that the resulting allylic alcohols were racemic, most likely due to a rapid addition reaction promoted by LiX (X = Br and Cl). To suppress the LiX promoted reaction, a series of inhibitors was screened. It was found that 20–30 mol % tetraethylethylene diamine (TEEDA) inhibited LiCl without inhibiting the chiral zinc-based Lewis acid. In this fashion, (Z)-disubstituted allylic alcohols were obtained with up to 98% ee. The asymmetric (Z)-vinylation could be coupled with tandem diastereoselective epoxidation reactions to provide epoxy alcohols and allylic epoxy alcohols with up to three contiguous stereogenic centers, enabling the rapid construction of complex building blocks with high levels of enantio- and diastereoselectivity.

Introduction

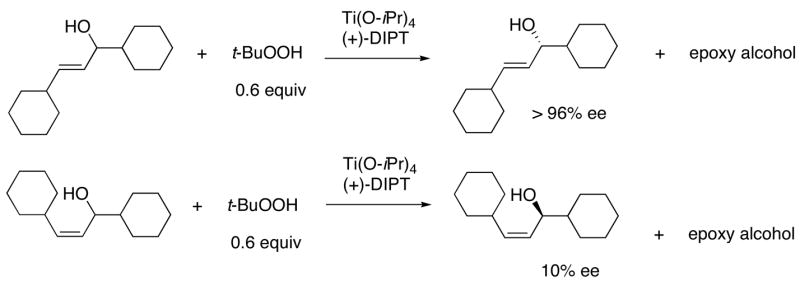

Enantioenriched allylic alcohols are among the most commonly used chiral building blocks and have been widely applied in natural and non-natural product synthesis.1–4 They are also precursors to enantioenriched epoxy alcohols,5–7,4,1,8–10 allylic amines,11–14 α- and β-amino acids,13,15 and cyclopropyl alcohols.16–19 Enantioenriched allylic alcohols are often isolated from kinetic resolution (KR) with the Sharpless-Katsuki asymmetric epoxidation catalyst.5–7,4 Although (E)-allylic alcohols are excellent substrates for the KR, (Z)-disubstituted allylic alcohols are not (Scheme 1).5–7,4 Other drawbacks to the KR include the need to separate the desired allylic alcohol from the epoxy alcohol product and a maximum yield of 50%.20

Scheme 1.

Application of the Sharpless-Katsuki Catalyst to the Kinetic Resolution of (E)- and (Z)-Allylic Alcohols.

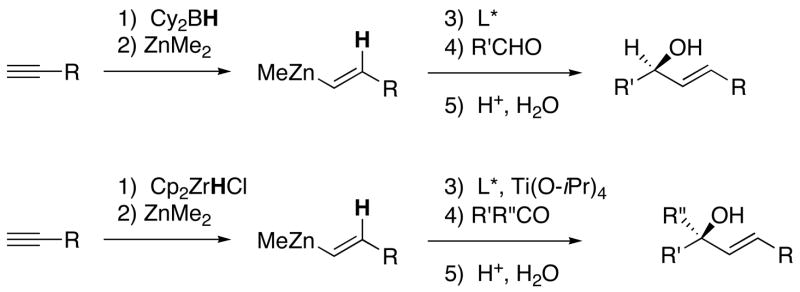

More efficient methods to prepare allylic alcohols include asymmetric vinylation of aldehydes21–25,13,15,8–10,26–28 or ketones29,30 (Scheme 2) and reductive coupling of alkynes and carbonyl compounds.31–36 These methods simultaneously generate the C-C bond and a stereogenic center in a single step. Almost all vinylation methods are initiated by hydrometallation of terminal alkynes, via hydroboration37,21–23 or hydrozirconation,38,24,25 followed by addition of the resulting (E)-vinyl organometallic reagents to aldehydes or ketones to furnish (E)-allylic alcohols (Scheme 2). Similar methods to prepare (Z)-allylic alcohols would require trans hydrometallations, which are rarely observed.39,40 One direct (Z)-vinylation of aldehydes has been reported involving the Nozaki-Hiyama-Kishi reaction with (Z)-vinyl halides. The only (Z)-vinyl halide in this study, however, underwent addition with 30% enantioselectivity.41

Scheme 2.

Catalytic Asymmetric Vinylation of Aldehydes and Ketones via Hydrometallation of Terminal Alkynes, Transmetallation, and Addition.

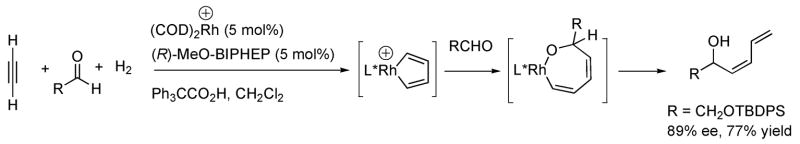

Progress toward the generation of enantioenriched (Z)-dienyl alcohols has recently been reported by the Krische group36 employing acetylene, hydrogen, and an aldehyde or α-ketoester in the presence of a rhodium catalyst (Scheme 3). Preliminary studies directed toward enantioselective versions of this dienylation reaction are promising.

Scheme 3.

Generation of (Z)-Dienyl Alcohols and Proposed Intermediates by Krische and Coworkers.

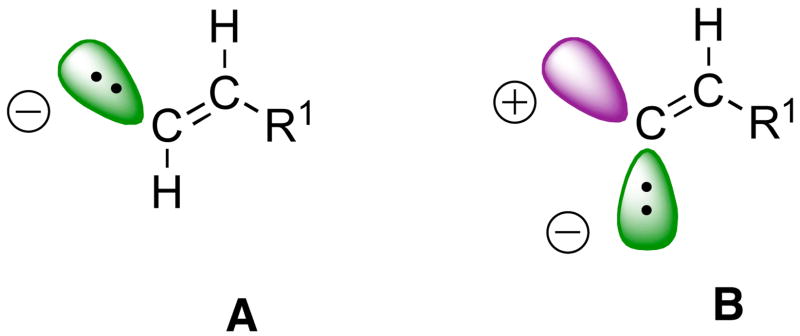

We have been interested in the development and applications of vinyl organometallic reagents that enable the construction of di- and trisubstituted olefins and allylic alcohols.13,15,8,9,30,29,10,19,42 Synthons for these species are shown in Figure 1. The synthon for the (E)-disubstituted vinyl groups represented in Scheme 2 (A, Figure 1) is readily derived from hydrometallation of terminal alkynes. A synthon for a (Z)-di- or trisubstituted vinyl group (Figure 1, B), on the other hand, contains two reactive positions, a nucleophilic site cis to R1 and an electrophilic site trans to R1.43–45 For generation of (Z)-disubstituted allylic alcohols, the nucleophilic reagent added to the electrophillic site is a hydride. In the development of reagents for synthon B, it is critical that the double bond stereochemistry be preserved during bond-forming processes.

Figure 1.

Synthon A represents (E)-disubstituted vinyl organometallics while synthon B represents (Z)-di- or trisubstituted reagents.

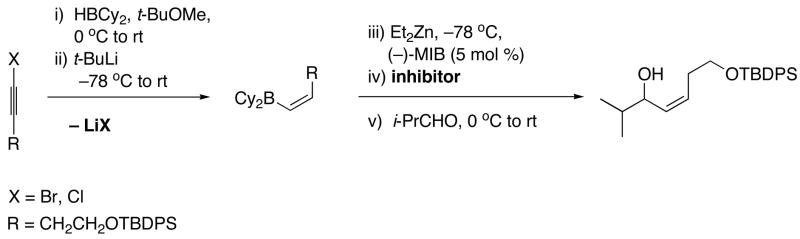

We recently reported a one-pot stereospecific method for the synthesis of (Z)-disubstituted allylic alcohols based on synthon B (Scheme 4).46 Initial hydroboration of 1-bromo-1-alkynes with dicyclohexylborane furnishes 1-bromo-1-alkenylboranes regioselectively. It is known that nucleophiles react with 1-bromo-1-alkenylboron derivatives via addition of the nucleophile to the open coordination site on boron followed by migration of the nucleophile47,48 or a boron alkyl to the vinylic position with inversion at the vinylic center.49–51,48,52,42 In our investigations we chose to use t-BuLi, which had been shown to be an excellent hydride source by Molander48 for the formation of (Z)-vinylboranes. Vinylboranes are fairly unreactive toward carbonyl additions. We envisioned that the (Z)-vinyl group would undergo boron to zinc transmetallation with dialkylzinc reagents to generate more reactive vinylzinc reagents. In fact, the increased reactivity of the vinylzinc reagent enabled additions to aldehydes to proceed smoothly to generate (Z)-allylic alcohols.46 Using this method, a variety of racemic (Z)-allylic alcohols were prepared in high yields. Additions of (Z)-vinyl groups to enantioenriched protected α- and β-hydroxy aldehydes resulted in formation of (Z)-allylic alcohols with high diastereoselectivity.46 Unfortunately, attempts at enantioselective versions of this transformation afforded only racemic products.

Scheme 4.

Our Stereospecific Method for the Synthesis of (Z)-Allylic Alcohols.

We now disclose the first general and direct catalytic asymmetric synthesis of (Z)-allylic alcohols. The application of this method to the one-pot preparation of highly functionalized epoxy alcohols and allylic epoxy alcohols is also demonstrated. These reactions lead to a rapid increase in molecular complexity and enable the synthesis of highly functionalized chiral building blocks.

Experimental Section

General Methods

All reactions were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere with oven-dried glassware using standard Schlenk or vacuum line techniques. The progress of all reactions was monitored by thin-layer chromatography which was performed on Whatman precoated silica gel 60 K6F plates and visualized by ultra-violet light or by staining with phosphomolybdic acid. t-BuOMe was distilled from Na/benzophenone and hexanes was dried through alumina columns. Tetraethylethylene diamine (TEEDA) was distilled and stored under nitrogen. The 1H NMR and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were obtained on a Brüker AM-500 Fourier transform NMR spectrometer at 500 and 125 MHz, respectively. 1H NMR spectra were referenced to tetramethylsilane in CDCl3 or residual protonated solvent; 13C{1H} NMR spectra were referenced to residual solvent. Analysis of enantiomeric excess was performed using a Hewlett-Packard 1100 Series HPLC and a chiral column specific for each compound. The optical rotations were recorded using a JASCO DIP-370. Infrared spectra were obtained using a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 100 series spectrometer. All reagents were purchased from Aldrich or Acros unless otherwise described. 1-Bromo-1-alkynes53 and 1-chloro-1-alkynes54 were made according to known procedure. All commercially available aldehyde substrates were distilled prior to use. Silica gel (Silicaflash P60 40–63 μm, Silicycle) was used for air-flashed chromatography and deactivated silica gel was prepared by addition of 15 mL NEt3 to 1 L of silica gel. Complete experimental procedures and characterization are located in the Supporting Information.

Caution

Dialkylzinc reagents and t-BuLi are pyrophoric. Care must be used when handling solutions of these reagents.

Synthesis of (Z)-Disubstituted Allylic Alcohols

Preparation o f (Z)-5-(tert-butyl-diphenyl-silanyloxy)-1-phenyl-pent-2-en-1-ol (3ac)

Dicyclohexylborane (88 mg, 0.5 mmol) was weighed into a Schlenk flask under nitrogen and dry t-BuOMe (1 mL) was added. tert-Butyl-(4-chloro-but-3-ynyloxy)-diphenyl-silane (1a, 160 μL, 0.5 mmol) was then added slowly to the reaction mixture at 0 °C. After 15 min, the solution was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 45 min, resulting in a clear solution. t-BuLi (0.37 mL, 0.55 mmol, 1.5 M pentane solution) was added dropwise at −78 °C and stirred for 60 min before the solution was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 60 min. During this time, a precipitate, presumably LiCl, formed. Diethylzinc (0.28 mL, 0.55 mmol, 2 M hexanes solution) was slowly added to the reaction mixture at −78 °C and the solution was stirred for 20 min. Next, TEEDA (14 μL, 0.066 mmol) and hexanes (4 mL) were added at –78 °C, the solution was warmed to 0 °C, and (−)-MIB (166 μL, 0.017 mmol) and benzaldehyde (34 μL, 0.33 mmol) were added. The reaction was then slowly warmed to room temperature and stirred for 16 hours. After the reaction was complete by TLC analysis, the mixture was diluted with 3 mL hexanes and quenched with H2O. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous solution was extracted with EtOAc (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (hexanes:EtOAc, 95:5) to give 3ac (83.8 mg, 61% yield) as an oil. The ee was determined by HPLC equipped with a Chiralcel AD-H column (hexanes:2-propanol, 99:1, flow rate = 0.5 mL/min), tr (1) = 38.2 min, tr (2) = 44.6 min, [α]D20 = + 131.11 (c = 0.001, CHCl3, 95% ee); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 1.12 (s, 9H), 2,20 (br, 1H), 2.45–2.51 (m, 1H), 2.58–2.65 (m, 1H), 3.73–3.80 (m, 2H), 5.50–5.51 (dd, J = 1.9, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.60–5.67 (dt, J = 7.8, 11.2 Hz, 1H), 5.77–5.81 (dd, J = 8.5, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (m 10H), 7.71 (m, 5H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ 19.4, 27.1, 31.4, 63.5, 69.9, 126.1, 127.6, 127.9, 128.7, 128.8, 129.9, 133.8, 134.5, 135.8, 143.7 ppm; IR (neat): 3369, 3069, 2931, 1958, 1890, 1824, 1656, 1589, 1472, 1427, 1389 cm−1; HRMS calcd for C27H32NaO2Si (M+Na)+: 439.2069, found 439.2054.

The number of peaks in the 13C NMR reflects the fact that the two phenyl groups attached to silicon are too far from the stereocenter to be seen as diastereotopic, thus only 4 signals are present for those two phenyl groups.

Asymmetric Addition/Diastereoselective Epoxidation Reactions

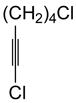

Preparation of [3-(4-chloro-butyl)-oxiranyl]-phenyl-methanol (4cc)

Dicyclohexylborane (88 mg, 0.5 mmol) was weighed into a Schlenk flask under nitrogen and dry t-BuOMe (1 mL) was added. 1,6-Dichloro-hex-1-yne (66 μL, 0.5 mmol) was then added slowly to the reaction mixture at 0 °C. After 15 min, the solution was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 45 min. t-BuLi (0.37 mL, 0.55 mmol, 1.5 M pentane solution) was added dropwise at −78 °C and the solution stirred for 60 min. The reaction mixture was then warmed to room temperature and stirred for an additional 60 min. During this time, a white precipitate formed. Diethylzinc (0.28 mL, 0.55 mmol, 2 M hexanes solution) was slowly added to the reaction mixture at −78 °C and the solution stirred for 20 min. Addition of TEEDA (14 μL, 0.066 mmol) and hexanes (4 mL) was performed at −78 °C and the solution warmed to 0 °C. Addition of (−)-MIB (166 μL, 0.017 mmol) was followed by addition of benzaldehyde (34 μL, 0.332 mmol). The reaction mixture was then slowly warmed to room temperature and stirred for 16 hours. After the reaction was complete by TLC analysis, the temperature was brought to −20 °C and ZnEt2 (0.28 mL, 0.55 mmol, 2 M solution in hexanes) was added. The reaction was stirred for 30 min and then TBHP (tert-butylhydroperoxide, 0.30 mL, 1.68 mmol, 5.5 M solution in decane) was added. After an additional 30 min at − 20 °C, Ti(Oi-Pr)4 (48 μL, 0.067 mmol, 1.4 M solution in hexanes) was added and the mixture stirred until the allylic alkoxide had been consumed (TLC, ~16 h). The reaction mixture was then quenched with 2 mL saturated aq. NH4Cl, stirred for 30 min at room temperature, and quenched with an aqueous solution of Na2S2O3. The organic and aqueous layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic layers were then washed with 5 mL brine, 5 mL H2O, dried over MgSO4, and filtered. The filtrate was collected, concentrated in vacuo, and the crude product was purified by column chromatography on deactivated silica gel (hexanes:EtOAc, 90:10) to give 4cc (53.6 mg, 67% yield) as an oil. [a]D20 = + 56.03 (c = 0.041, CHCl3); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 1.64 (m, 6H), 2.46 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 3.1 (m, 1H), 3.20 (dd, J = 4.4, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.56 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 4.58 (dd, J = 2.8, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (m, 5H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ 24.5, 28.0, 32.3, 44.9, 58.3, 61.4, 72.5, 126.4, 128.6, 129.0, 140.1 ppm; IR (neat): 3419, 3062, 3031, 2955, 2866, 1807, 1604, 1492, 1454, 1278, 1195, 1040 cm−1; HRMS calcd for C13H16OCl (M-OH)+:223.08897, found 223.08883. Analysis of diastereomeric ratio was performed by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Results and Discussion

When our (Z)-vinylation of aldehydes (Scheme 4) was conducted in the presence of the amino alcohol-based catalyst derived from (−)-MIB,55,56 the (Z)-allylic alcohol product was isolated in good yields, but the product was found to be racemic. This was surprising because the zinc-based catalyst derived from (−)-MIB is one of the most efficient and enantioselective amino alcohol-based catalysts known for carbonyl additions. The absence of enantioselectivity was attributed to the rapid addition reaction promoted by the liberated Lewis acid byproduct, LiBr (Scheme 4). Rather than attempt to remove the LiBr byproduct by filtration57 or centrifugation,58 which would be impractical on large scale, we decided to deactivate it.

Our first attempts to inhibit the salt byproduct were based on observations reported by Bolm. In a study involving the addition of Ph2Zn to aldehydes, Bolm and coworkers emphasized the beneficial effect of dimethoxy poly(ethyleneglycol) (DiMPEG) on the reaction enantioselectivity.57 They proposed that DiMPEG suppressed reactions catalyzed by trace achiral Lewis acids, including LiBr, allowing most of the arylation reaction to proceed via the ligand accelerated59 Lewis acid catalyzed pathway.60

To suppress the LiBr-promoted vinyl addition to aldehydes, we employed DiMPEG as inhibitor (Scheme 5). Addition of 5–7 mol % DiMPEG (MW 2000 g/mol) proved most effective, with enantioselectivities in the (Z)-vinylation reaching 86% (Table 1, entries 1–4). Although this result was exciting and promising, we found that the reactions were very sensitive to the mol % DiMPEG and enantioselectivities were difficult to reproduce. Tetraglyme was used as a DiMPEG analog but was significantly less effective at inhibiting LiBr (Table 1, entries 5–7). After significant effort to identify reliable polyether inhibitors, this strategy was abandoned.

Scheme 5.

Optimization of the Catalytic Asymmetric Generation of (Z)-Allylic Alcohols.

Table 1.

Enantioselective Addition of (Z)-Vinylzinc Reagents to Aldehydes in the Presence of Various Inhibitors (Scheme 5)

| entry | additive (mol %) | X | ee (%) | entry | additive (mol %) | X | ee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DiMPEG (5.5) | Br | 75 | 10 | none | Cl | 0 |

| 2 | DiMPEG (6) | Br | 79 | 11 | TEEDA (10) | Cl | 82 |

| 3 | DiMPEG (6.5) | Br | 86 | 12 | TEEDA (15) | Cl | 89 |

| 4 | DiMPEG (7) | Br | 80 | 13 | TEEDA (20) | Cl | 90 |

| 5 | tetraglyme (90) | Br | 10 | 14 | TEEDA (25) | Cl | 90 |

| 6 | tetraglyme (110) | Br | 26 | 15 | TEEDA (30) | Cl | 90 |

| 7 | tetraglyme (220) | Br | 5 | 16 | TEEDA (40) | Cl | 45 |

| 8 | TEEDA (20) | Br | 10 | ||||

| 9 | TEEDA (20) | Br | 10 |

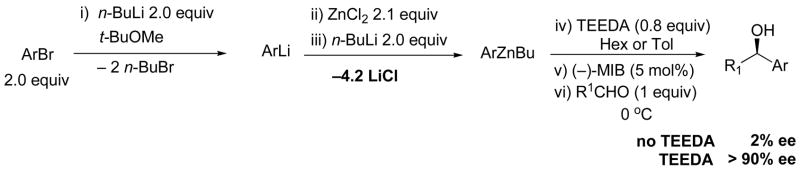

Instead, we turned to a diamine inhibitor that we had successfully used to solve a similar problem in our development of the first highly enantioselective one-pot asymmetric synthesis of enantioenriched diarylmethanols beginning from aryl bromides (Scheme 6).61 Like the vinylation in Scheme 4, initial attempts at the asymmetric arylation reactions also resulted in formation of essentially racemic products. In the transmetallation reactions used to generate the aryl group donor, Ar-Zn(n-Bu), over 4 equiv LiCl were formed. As seen in the vinylation reactions, this Lewis acidic byproduct was significantly faster at promoting the aryl addition to provide diarylmethanols than the chiral amino alcohol-based catalyst, resulting in formation of racemic product. Another possible mechanism for the LiCl accelerated addition to aldehydes is via formation of a more reactive zincate by interaction of the LiCl with the organozinc to generate R2ZnCl−Li+.62,45 Although this mechanism cannot be ruled out at this time, we favor the Lewis acid activation of the aldehyde on the basis of the results in the following paragraph.

Scheme 6.

Asymmetric Arylation of Aldehydes with TEEDA to Inhibit LiCl.

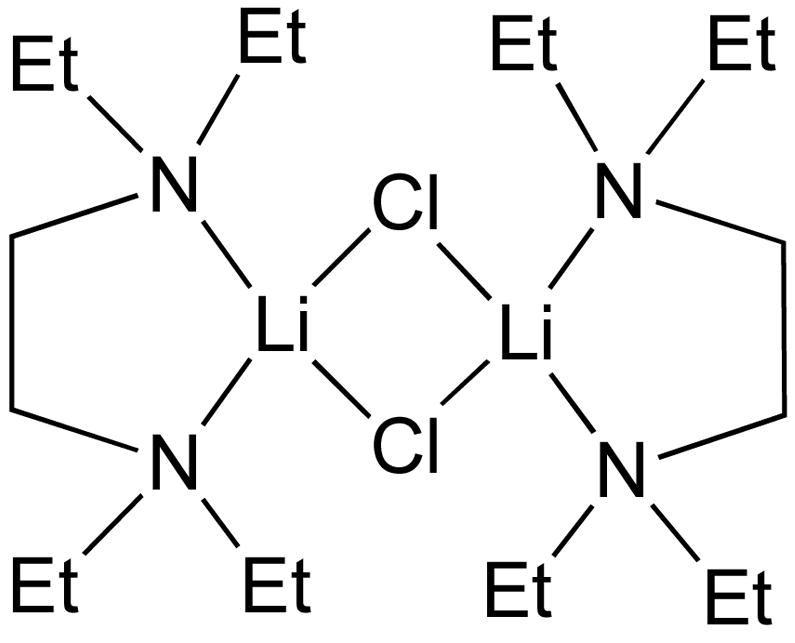

The key to our successful development of an asymmetric arylation system was inhibition of the LiCl byproduct with tetraethylethylene diamine (TEEDA). The diamine is believed to chelate the LiCl to form a chloride-bridged dimer [(TEEDA)LiCl]2 that is coordinatively saturated and catalytically inactive (Figure 2).63,64 Using this technique, the racemic background reaction was completely suppressed, resulting in formation of diarylmethanols with enantioselectivities as high as 97%.

Figure 2.

Possible structure of the coordinatively saturated TEEDA adduct of LiCl.

When our diamine-based strategy in Scheme 6 was applied to the synthesis of (Z)-allylic alcohols in Scheme 5, enantioselectivities peaked at 10% under our best conditions (Table 1, entries 8 and 9). These results suggested to us that inhibition of LiBr would be significantly different from inhibition of LiCl. We speculate that the bromide analogs of [(TEEDA)LiCl]n (Figure 2) dissociate more readily to generate an open coordination site capable of aldehyde activation. Rather than search for a new inhibitor for LiBr, we chose to examine 1-chloro-1-alkynes in this process, which would generate LiCl.

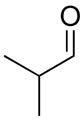

Examination of 1-chloro-1-alkynes was approached in a similar fashion to the optimization of 1-bromo-1-alkynes. When 1-bromo-1-alkynes were employed in our previous study46 (Scheme 4), we found it necessary to perform the addition of t-BuLi in THF. A solvent switch was then needed, because the vinylzinc addition proceeds in low yield in THF. Using the 1-chloro-1-alkynes, however, the entire reaction could be performed in t-BuOMe solvent, without the need to switch solvents. Hydroboration of 1-chloro-1-alkynes (1.5 equiv) with Cy2BH (1.5 equiv) proceed in 1 h at 0 °C – room temperature with excellent regioselectivity. Reaction of the resulting 1-chloro-1-vinylborane with t-BuLi (1.65 equiv) occurred with inversion at the vinylic center, generating the (Z)-vinylborane. Transmetallation with diethylzinc (1.65 equiv) and addition to an aldehyde (1 equiv) in the presence of the (−)-MIB-based catalyst provided the racemic allylic alcohol. Repeating the sequence with the addition of increasing amounts of TEEDA resulted in the formation of enantioenriched (Z)-allylic alcohol products (Table 1, entries 10 – 16). The highest enantioselectivities were obtained with 20–30 mol % TEEDA. Further increases in the mol % diamine caused a decrease in both enantioselectivity and yield. This observation is likely due to inhibition of the chiral zinc-based catalyst by the diamine, allowing the uncatalyzed background reaction to become competitive with the catalyzed addition, eroding the product ee. Note that less than an equivalent of diamine per equivalent of LiCl is needed. Much of the LiCl precipitates from solution and is not active in promoting the addition reaction.

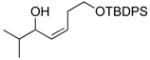

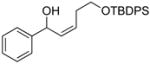

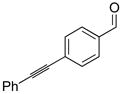

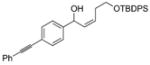

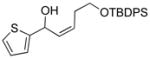

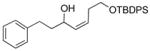

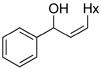

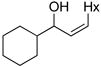

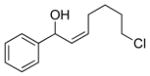

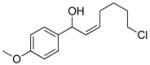

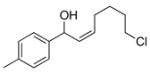

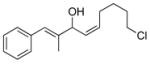

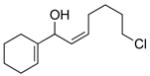

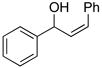

With the optimized conditions in Table 1, we examined the scope of the asymmetric vinylation (Table 2). Employing 20–30 mol % TEEDA, a variety of 1-chloro-1-alkynes and aldehydes underwent the addition in good yields (61–93%, based on aldehyde as the limiting reagent) and good to excellent enantioselectivities (75–98%). 1-Chloro-1-alkynes bearing a TBDPS protected alcohol (entries 1 – 6), alkyl (entries 7 and 8), chloro alkyl (entries 9 – 16), or phenyl groups (entries 17 and 18) were successfully employed in the asymmetric vinylation reaction. Although aliphatic aldehydes with α-branching underwent addition with high enantioselectivity (84 – 90%, entries 1, 8, and 11), β-branched isovaleraldehyde was a more challenging substrate, undergoing addition with 76% enantioselectivity (entry 2). Likewise, dihydrocinnamaldehyde underwent addition with 75% enantioselectivity (entry 6). α,β-Unsaturated aldehydes reacted to form dienols with 88–94% enantioselectivity (entries 15 and 16). Aryl aldehydes were also good substrates for the vinylation reaction, providing benzylic alcohols with enantioselectivities between 86 and 98%. The electron withdrawing trifluoromethyl benzaldehyde exhibited the lowest enantioselectivity of this class of substrates, possibly due to an earlier transition state with less bond formation and reduced steric bias (entry 12). The heterocyclic aldehyde, 2-thiophene carboxaldehyde, proved to be an excellent substrate for (Z)-vinylations proceeding in 92–94% enantioselectivity (entries 5, 10, and 18). This route to thiophene containing allylic alcohols avoids potential problems with catalyst poisoning that can arise in hydrogenation of thiophene-containing propargylic alcohols.65–70 Beyond catalyst poisoning, over reduction and contamination with the undesired (E)-isomer have been reported to be problematic.70 Similarly, the alkyne-bearing product in entry 4 would be difficult to prepare by selective Lindlar reduction.

Table 2.

Scope of the Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of (Z)-Allylic Alcohols

| entry | chloroalkyne | Aldehyde | product | yielda (%) | ee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

1a |

2a |

3aa |

61 | 90 |

| 2 |

2b |

3ab |

74 | 76 | |

| 3 |

2c |

3ac |

61 | 95 | |

| 4 |

2d |

3ad |

84 | 98 | |

| 5 |

2e |

3ae |

69 | 93 | |

| 6 |

2f |

3af |

72 | 75 | |

|

| |||||

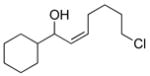

| 7 |

1b |

2c |

3bc |

63 | 93 |

| 8 |

2f |

3bg |

81 | 84 | |

|

| |||||

| 9 |

1c |

2c |

3cc |

84 | 88 |

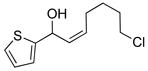

| 10 |

2e |

3ce |

73 | 94 | |

| 11 |

2f |

3cg |

74 | 88 | |

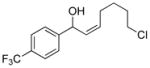

| 12 |

2g |

3ch |

72 | 86 | |

| 13 |

2h |

3ci |

84 | 93 | |

| 14 |

2i |

3cj |

93 | 97 | |

| 15 |

2j |

3ck |

73 | 88 | |

| 16 |

2k |

3cl |

80 | 94 | |

|

| |||||

| 17 |

1d |

2c |

3dc |

82 | 97 |

| 18 |

2e |

3de |

63 | 92 | |

Yields based on aldehyde as the limiting reagent.

Important in the development of practical methods with potential utility in target oriented synthesis is the evaluation of scalability. With this in mind, we examined the substrate combination in entry 14 using 5.0 mmol of the aldehyde. The desired (Z)-allylic alcohol was obtained in 79% yield at this scale with 96% ee. The high yield and enantioselectivity in this reaction bode well for large-scale applications of these asymmetric addition reactions.

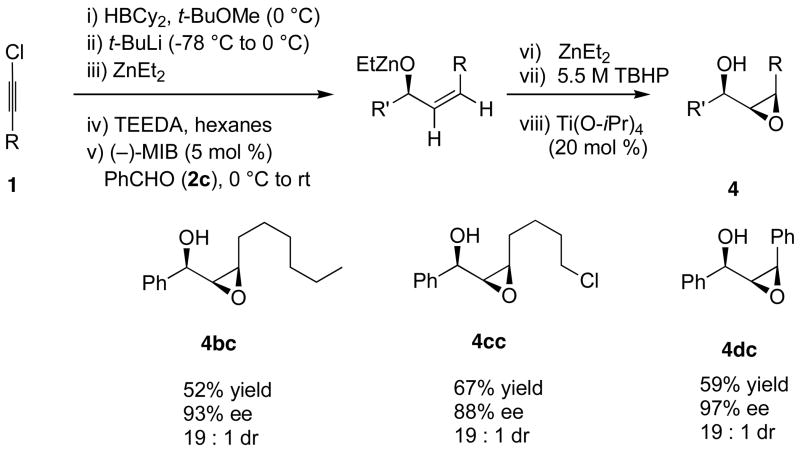

Having developed a viable method for the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of (Z)-disubstituted allylic alcohols, we wanted to briefly examine the potential application of this process in tandem addition/epoxidation reactions. We recently developed methods for tandem asymmetric alkylation of enones71,72 and enals9,8,10 followed by diastereoselective epoxidation of the resulting allylic alkoxide to provide epoxy alcohols with up to three contiguous stereogenic centers. The oxidant in the epoxidation was a zinc peroxide generated upon reaction of either TBHP or dioxygen with dialkylzinc reagents. Adaptation of our addition/epoxidation method to the (Z)-vinylation reagents is illustrated in Scheme 7. Initially we were concerned that the reaction would be hampered by the presence of the TEEDA, due to its known coordination to titanium alkoxides73 or oxidation to the N-oxide, as was observed in the KR of racemic β-amino alcohols by Sharpless.74 Fortunately, these side reactions did not interfere with the epoxidation.

Scheme 7.

Tandem Asymmetric Addition/Diastereoselective Epoxidation.

The generation of the allylic zinc alkoxide was performed as outlined in Scheme 5. Rather than addition of water to quench the allylic alkoxide intermediate, however, 2 equiv of diethylzinc were injected into the flask. Dropwise addition of a 5.5 M solution of TBHP in decane was then followed by titanium tetraisopropoxide (20 mol %). The epoxidations were conducted at −20 °C and stirred for 24 h before workup. The crude epoxy alcohols were chromatographed and isolated in 52 – 67% yield with excellent dr (19:1 in each case, Scheme 7).

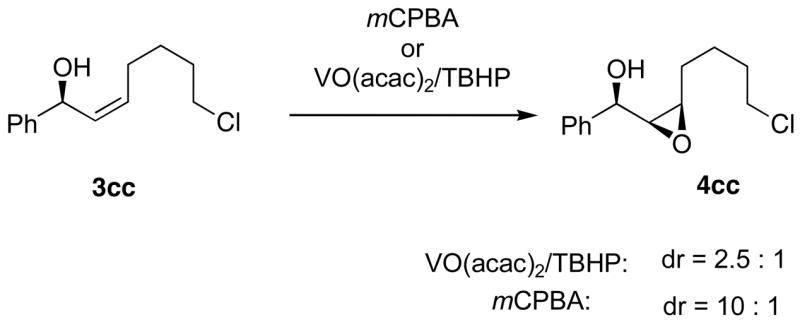

To aid in the assignment of the relative stereochemistry in the epoxy alcohol products in Scheme 7, we examined the diastereoselective epoxidation of an isolated allylic alcohol with the complementary epoxidizing agents mCPBA and VO(acac)2/TBHP (Scheme 8). It is well known that VO(acac)2/TBHP exhibits high diastereoselectivity with allylic alcohols that possess A1,2 strain in one of the diastereomeric epoxidation transition states. In contrast, mCPBA is known to epoxidized with high diastereoselectivity when allylic alcohols lead to A1,3 strain in one of the diastereomeric epoxidation transition states.3 Subjecting the preformed allylic alcohol in Scheme 8 to the typical epoxidation conditions with VO(acac)2/TBHP and mCPBA afforded the epoxy alcohols with 2.5:1 and 10:1 dr, respectively. The mCPBA epoxidation resulted in high stereoselectivity and formed the same diastereomer as our one-pot addition/epoxidation procedure. This observation indicates that the syn diastereomer is formed in the tandem reaction, as shown in Scheme 7. Furthermore, the stereochemistry of 4dc was assigned by derivatization with (−)-camphanic acid chloride to afford the expected ester, which was characterized by X-ray crystallography (see Supporting Information).

Scheme 8.

Epoxidation of the Isolated Allylic Alcohol with VO(acac)2/TBHP and mCPBA.

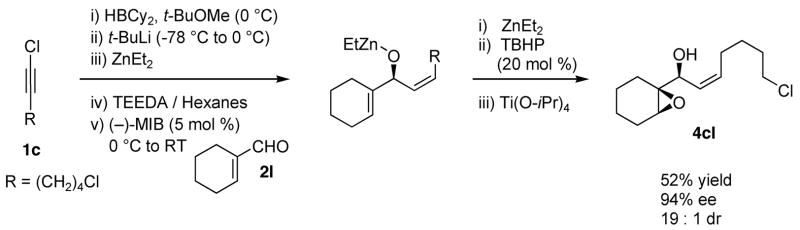

Having demonstrated that the epoxidation of the (Z)-allylic alkoxide could be performed in the tandem addition/epoxidation reaction, we wanted to explore the preferential epoxidation of a more substituted double bond in the presence of the (Z)-vinyl group. Thus, addition of the (Z)-vinylzinc reagent to cyclohexenecarboxaldehyde generated the intermediate dienyl alkoxide, which was subsequently exposed to zinc peroxide and titanium tetraisopropoxide to furnish the allylic epoxy alcohol derived from oxidation of the more electron rich trisubstituted double bond in 52% yield with 94% ee and 19:1 dr. The results in Scheme 7 and Scheme 9 highlight a unique feature of this epoxidation system: the ability to perform highly diastereoselective epoxidations with either A1,2 or A1,3 strain in one of the diastereomeric epoxidation transition states.10 In contrast, low diastereoselectivity is observed with mCPBA when selectivity is dependent on A1,2 strain in one of the diastereomeric transition states and with VO(acac)2/THBP or Ti(Oi-Pr)4/TBHP when selectivity is dependent on A1,3 strain.3

Scheme 9.

Tandem Asymmetric Addition/Diastereo- and Chemoselective Epoxidation.

Outlook and Conclusions

Herein we have presented the first general highly enantioselective addition of (Z)-vinyl groups to aldehydes to afford enantioenriched (Z)-allylic alcohols. Employing readily available 1-chloro-1-alkynes, hydroboration, addition of t-BuLi and transmetallation to zinc affords (Z)-vinylzinc intermediates. The resulting (Z)-vinylzinc reagents undergo addition to aldehydes with high enantioselectivity in the presence of a zinc-based catalyst derived from MIB. A variety of enantioenriched (Z)-allylic alcohols can be accessed in this simple one-pot procedure, including some that would be difficult to prepare using Lindlar hydrogenations of enantioenriched propargylic alcohols due to catalyst poisoning or functional group incompatibility.

Furthermore, we have found the conditions for the (Z)-vinylation of aldehydes are compatible with our diastereoselective epoxidation procedure, allowing access to epoxy alcohols and allylic epoxy alcohols with three contiguous stereogenic centers with high ee and dr. Previous methods to prepare such compounds required several synthetic steps and purifications. Using the procedures introduced herein, such compounds can be readily synthesized in a single flask without isolation or purification of intermediates.

Given the rapid increase in molecular complexity with defined stereochemical outcome, we anticipate that these methods will be very useful in enantioselective synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Procedures, full characterization, and stereochemical assignments of new compounds are available (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NSF (CHE-065210) and NIH (National Institute of General Medical Sciences GM58101) for partial support of this work. We are also grateful to Akzo Nobel Polymer Chemicals for a gift of dialkylzinc reagents.

References

- 1.Katsuki T, Martin VS. Org React. 1996:1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonini C, Righib G. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:4981–5021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam W, Wirth T. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:703–710. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katsuki T. In: Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis. Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Vol. 2. Springer; Berlin: 1999. pp. 621–648. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martín VS, Woodard SS, Katsuki T, Yamada Y, Ikeda M, Sharpless KB. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:6237–6240. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharpless KB, Behrens CH, Katsuki T, Lee AWM, Martin VS, Takatani M, Viti SM, Walker FJ, Woodard SS. Pure & Appl Chem. 1983;55:589–604. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Y, Klunder JM, Hanson RM, Masamune H, Ko SY, Sharpless KB. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5765–5780. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lurain AE, Maestri A, Kelly AR, Carroll PJ, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13608–13609. doi: 10.1021/ja046750g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lurain AE, Carroll PJ, Walsh PJ. J Org Chem. 2005;70:1262–1268. doi: 10.1021/jo048345d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowley Kelly A, Lurain AE, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14668–14674. doi: 10.1021/ja051291k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johannsen M, Jørgensen KA. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1689–1708. doi: 10.1021/cr970343o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overman LE. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:2901–2910. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YK, Lurain AE, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12225–12231. doi: 10.1021/ja027271p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen B, Mapp AK. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5364–5365. doi: 10.1021/ja0490469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lurain AE, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10677–10683. doi: 10.1021/ja035213d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charette AB, Marcoux JF. Synlett. 1995:1197–1207. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charette AB, Lebel H. J Org Chem. 1995;60:2966–2967. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lebel H, Marcoux JF, Molinaro C, Charette AB. Chem Rev. 2003;103:977–1050. doi: 10.1021/cr010007e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HY, Lurain AE, García-García P, Carroll PJ, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13138–13139. doi: 10.1021/ja0539239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keith JM, Larrow JF, Jacobsen EN. Adv Synth Catal. 2001;1:5–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oppolzer W, Radinov RN. Helv Chim Acta. 1992;75:170–173. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oppolzer W, Radinov RN. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1593–1594. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oppolzer W, Radinov RN, Brabander JD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:2607–2610. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wipf P, Ribe S. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6454–6455. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wipf P, Xu W, Takahashi H, Jahn H, Coish PDG. Pure Appl Chem. 1997;69:639–644. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bräse S, Dahmen S, Höfener S, Lauterwasser F, Kreis M, Ziegert RE. Synlett. 2004:2647–2669. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richmond ML, Sprout CM, Seto CT. J Org Chem. 2005;70:8835–8840. doi: 10.1021/jo051313l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sprout CM, Richmond ML, Seto CT. J Org Chem. 2005;70:7408–7417. doi: 10.1021/jo051342w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6538–6539. doi: 10.1021/ja049206g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8355–8361. doi: 10.1021/ja0425740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller KM, Huang WS, Jamison TF. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3442–3443. doi: 10.1021/ja034366y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller KM, Jamison TF. Org Lett. 2005;7:3077–3080. doi: 10.1021/ol051075g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt F, Rudolph J, Bolm C. Synthesis. 2006:3625–3630. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens BD, Bungard CJ, Nelson SG. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6397–6402. doi: 10.1021/jo0605851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montgomery J. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:467–473. doi: 10.1021/ar990095d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kong JR, Ngai MY, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:718–719. doi: 10.1021/ja056474l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srebnik M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:2449–2452. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hart DW, Schwartz J. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:8115–8116. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohmura T, Yamamoto Y, Miyaura N. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4990–4991. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexakis A, Duffault JM. Tetrahedron Letters. 1988;29:6243–6246. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wan Z-K, Choi H-w, Kang F-A, Nakajima K, Demeke D, Kishi Y. Org Lett. 2002;4:4431–4434. doi: 10.1021/ol0269805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen YK, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3702–3703. doi: 10.1021/ja0396145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kocienski P, Barber C. Pure and Applied Chemistry. 1990;62:1933–1940. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kocienski P, Klein W, editors. Wieweg. 1993. p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shibli A, Varghese JP, Knochel P, Marek I. Synlett. 2001:818–820. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jeon SJ, Fisher EL, Carroll PJ, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9618–9619. doi: 10.1021/ja061973n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corey EJ, Albonico SM, Koelliker U, Schaaf TK, Varma RK. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1971;93:1491–1493. doi: 10.1021/ja00735a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell JBJ, Molander GA. J Organomet Chem. 1978;156:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zweifel G, Arzoumanian H. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:5086–5088. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Negishi E, Yoshida T. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1973:606–607. doi: 10.1021/ja00801a056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Negishi E, Williams RM, Lew G, Yoshida T. J Organomet Chem. 1975;92:C4–C6. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown HC, Imai T, Bhat NG. J Org Chem. 1986;51:5277–5282. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leroy J. Organic Syntheses. 1997;74:212–216. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray RE. Synth Commun. 1980;10:345–349. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen YK, Jeon SJ, Walsh PJ, Nugent WA. Org Synth. 2005;82:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nugent WA. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1999:1369–1370. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rudolph J, Hermanns N, Bolm C. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3997–4000. doi: 10.1021/jo0495079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weber B, Seebach D. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:7473–7484. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berrisford DJ, Bolm C, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1995;34:1059–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmidt F, Stemmler RT, Rudolph J, Bolm C. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:454– 470. doi: 10.1039/b600091f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim JG, Walsh PJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:4175–4178. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meyer C, Marek I, Courtemanche G, Normant JF. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:11665–11692. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chitsaz S, Pauls J, Neumuller B. Z Naturforsch, B. 2001;56:245–248. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoffmann D, Dorigo A, Schleyer PvR, Reif H, Stalke D, Sheldrick GM, Weiss E, Geissler M. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:262–269. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rylander PN. Catalytic Hydrogenation Over Platinum Metal. Academic Press; New York: 1967. p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Freifelder M. Catalytic Hydrogenation in Organic Synthesis: Procedures and Commentary. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1978. p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Belen’kii LI, Gol’dfarb YL. In: In Thiophene and Its Derivatives, The Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds. pt 1. Gronowitz S, editor. Vol. 44. John Wiley & Son; New York: 1985. p. 465. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maxted EB, Evans HC. Journal of the Chemical Society. 1937:603–606. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bateman L, Shipley FW. Journal of the Chemical Society. 1958:2888–2890. [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Sousa PT, Jr, Taylor RJK. J Braz Chem Soc. 1993;4:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jeon SJ, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9544–9545. doi: 10.1021/ja036302t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jeon SJ, Li H, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16416–16425. doi: 10.1021/ja052200m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Larsen AO, White PS, Gagné MR. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:4824–4828. doi: 10.1021/ic990473a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miyano S, Lu LDL, Viti SM, Sharpless KB. J Org Chem. 1985;50:4350–4360. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Procedures, full characterization, and stereochemical assignments of new compounds are available (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.