Abstract

Protein transduction (PT) is a method for delivering proteins into mammalian cells. PT is accomplished by linking a small peptide tag—called a PT domain (PTD)—to a protein of interest, which generates a functional fusion protein that can penetrate efficiently into mammalian cells. In order to study the functions of a transcription factor (TF) of interest, expression plasmids that encode the TF often are transfected into mammalian cells. However, the efficiency of DNA transfection is highly variable among different cell types and is usually very low in primary cells, stem cells and tumor cells. Zinc-finger transcription factors (ZF-TFs) can be tailor-made to target almost any gene in the human genome. However, the extremely low efficiency of DNA transfection into cancer cells, both in vivo and in vitro, limits the utility of ZF-TFs. Here, we report on an artificial ZF-TF that has been fused to a well-characterized PTD from the human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) transcriptional activator protein, Tat. This ZF-TF targeted the endogenous promoter of the human VEGF-A gene. The PTD-attached ZF-TF was delivered efficiently into human cells in vitro. In addition, the VEGF-A-specific transcriptional repressor retarded the growth rate of tumor cells in a mouse xenograft experiment.

INTRODUCTION

Protein transduction is a powerful method for delivering proteins into mammalian cells both in vivo and in vitro (1–6). Although there are several different protein delivery methods, the most widely used approach is to link a small peptide tag—called a protein transduction domain (PTD)—to a protein of interest, which generates a fusion protein that can penetrate efficiently into mammalian cells. Dozens of diverse proteins, including transcription factors (TFs) (7) and enzymes (5,8,9), have been delivered successfully into cells via protein transduction methods.

Unlike growth factors, cytokines and peptide hormones, which function extracellularly, TFs do their job inside the cells. In order to study the functions of a TF of interest, expression plasmids that encode the TF often are transfected into mammalian cells. The efficiency of DNA transfection is highly variable among different cell types and is usually very low in primary cells, stem cells and tumor cells (10,11).

Artificial TFs based on custom-designed zinc-finger proteins (ZFPs) provide an unique opportunity to regulate a gene of interest (12–22). Zinc-finger-transcription factors (ZF-TFs) can be tailor-made to target almost any gene in the human genome. For example, we and others have produced ZF-TFs that selectively regulate diverse genes both in vivo and in vitro. We have found, however, that the extremely low efficiency of DNA transfection into cancer cells limits the utility of ZF-TFs in cancer therapy.

Here, we report on an artificial ZF-TF that has been fused to a well-characterized PTD from the human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) transcriptional activator protein, Tat. This ZF-TF was delivered efficiently into human cells both in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of plasmids

Vector constructs for the expression of ZF-TFs in mammalian cells are described elsewhere (14). Nucleic acids that encode preassembled ZFPs were inserted into the pTAT expression plasmid (2) as follows. First, KpnI restriction sites were added to the ZFP coding sequences with the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a forward primer that contained a KpnI site at the 5′-end. The inserts and vector (pTAT) were then prepared by digestion with KpnI and XhoI. After ligation, the pTAT-ZFP constructs were sequenced. When the pTAT-ZFP plasmids were constructed, nucleotide sequences were produced that encode polypeptides with the following structure (from N- to C-terminus): an ATG start codon, a hexa-histidine tag, the HIV Tat PTD sequence, a nuclear localization signal (NLS), and an array of ZF domains that were each fused to an effector domain isolated from TFs. We refer to these polypeptides as PTDTAT–ZF-TF fusion proteins.

Expression and purification of PTDTAT–ZF-TF fusion proteins

Expression vectors that encode the various transducible chimeric PTDTAT–ZF-TF fusion proteins were transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) pLysS, and the resulting bacterial cells were plated onto LB-agarose containing ampicillin. Single colonies of E. coli that had been transformed with PTDTAT–ZF-TF were picked and inoculated into selection medium. The initial culture was inoculated into 300 ml of LB selection medium and cultivated until the culture reached an OD of ∼0.8. Then, 1 mM IPTG was added to the culture to induce protein expression and the cells were incubated for ∼2 h at 37°C.

Purified preparations of the PTDTAT–ZF-TF fusion proteins were obtained with the use of Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the PTDTAT–ZF-TF—expressing BL21 cells were subjected to centrifugation, and the cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris·Cl, 8 M Urea, protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 8.0) and lyzed by five cycles of sonication on ice with a Fischer Scientific 550 Sonic Dismembrator (each cycle included 10 s of sonication followed by a 30 s pause). The lysates were then incubated with Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen) for 45 min, and the beads were washed twice with wash solution (100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris–Cl, 8 M urea, pH 6.3). Protein was eluted from the beads with elution buffer (100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris–Cl, 8 M urea, pH 4.5) and dialyzed against refolding solution (20 mM Tris, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM ZnCl, pH 8.0) at 4°C. The dialyzed proteins were then concentrated using CENTRICON™ filtration, quantified with the Bradford assay, subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), and visualized with Coomassie blue staining. The purified protein preparations were stored at −70°C in refolding solution with 10% glycerol.

Protein transduction into HEK 293 cells and reporter assay

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). For the luciferase assay, 104 cells/well were precultured in a 96-well plate. Using a Lipofectamine transfection kit (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA), HEK293 cells were transfected with 15 ng of a reporter plasmid pGL-VEGF in which the native VEGF promoter was fused to the luciferase gene in pGL3-basic (Promega) and 68.5 ng of internal control reporter pRL-SV40 encoding Renilla luciferase. Cells were then treated with different amount of purified PTDTAT–F435-KRAB protein. After 2 h exposure to PTDTAT–F435-KRAB protein, cells were washed and incubated for 24 h with fresh growth medium. The luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase™ Reporter Assay System (Promega).

For the measurement of VEGF mRNA and protein, 5 × 104 cells/well were precultured in a 24-well plate. Cells were treated with 250 μg of purified PTDTAT–F435-KRAB protein for 2 h, then were washed with fresh growth medium. Cells and culture medium were harvested at 48 h after protein transduction. Methods for VEGF mRNA and protein analysis are described elsewhere (14).

Mouse xenograft experiments

Human colorectal cancer cells (the HM7 cell line) were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Confluent HM7 cell cultures were harvested by brief trypsinization (0.05% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA in Hanks’ balanced salt solution without calcium and magnesium), washed three times with a calcium- and magnesium-free PBS solution and resuspended at a final concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml in serum-free DMEM.

Single-cell suspensions were confirmed by phase-contrast microscopy, and cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion; only single-cell suspensions with a viability of >90% were used. Pathogen-free female BALB/cAnNCrj-nu athymic nude mice (4-weeks old; Charles River Laboratories, Kanazawa, Japan) were anesthetized, by inhalation, with diethyl ether and 5 × 105 HM7 colon cancer cells in 100 µl of serum-free DMEM were inoculated subcutaneously into the mice's dorsal sacs. When the tumors were between 50 and 100 mm3, the animals were paired, matched into control groups (PBS) and treatment groups [PTDTAT–ZF-TF alone, 5-flurouracil (5-FU) alone, or PTDTAT–ZF-TF plus 5-FU (each at 35 mg/kg/injection)]. Mice were treated intratumorally with either (i) 10 PTDTAT–ZF-TF injections (one per day); (ii) five 5-FU injections (one per day); (iii) 10 PBS injections (one per day) or (iv) for the group that received PTDTAT–ZF-TF and 5-FU, five PTDTAT–ZF-TF and five 5-FU injections (one each per day for the first 5 days) and the five PTDTAT–ZF-TF and five PBS injections (one each per day for the next 5 days). The mice were surveyed regularly, tumors were measured with a caliper and tumor volumes were determined using the following formula: volume = 0.5 × (width)2 × length. Each experimental group consisted of eight animals and a P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Immunohistochemistry

After the mice were sacrificed, tumors were removed and bisected as described elsewhere (23). To immunolocalize tumor blood vessels, cryosections were stained with a monoclonal rat antimouse CD31 antibody (PECAM-1; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:50. Visualization of the antigen–antibody reaction was carried out using an antirat immunoglobulin—horseradish peroxidase detection kit (BD PharMingen), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Vessel density was determined by counting the stained vessels at a magnification of 200×.

RESULTS

VEGF-A-specific transcriptional repressors

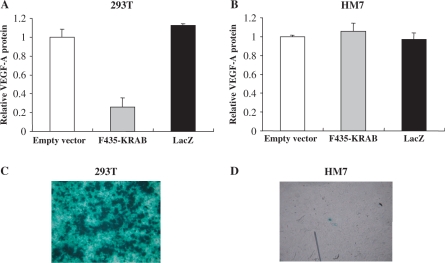

We first tested whether plasmids that encode ZF-TFs could be transfected efficiently into cancer cells in vitro. We chose a ZFP [termed F435 in Bae et al(24)] that had been designed to recognize two nearly identical 9-bp DNA sequences in the promoter of the human VEGF-A gene. We prepared a plasmid that encodes a ZF-TF (termed F435-KRAB) that consists of the F435 ZFP and the Kruppel-associated box (KRAB) transcriptional repression domain derived from the human KOX1 protein. Noncancerous human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells and human cancer HM7 cells were transfected with the plasmid that encodes F435-KRAB or the plasmid that encodes the Lac Z product, β-galactosidase using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). As shown in Figure 1A and B, F435-KRAB efficiently suppressed the expression of VEGF-A in 293 cells, but not in HM7 cells. HEK 293 cells and HM7 cells transfected with the LacZ plasmid were stained to visualize the enzyme activity (Figure 1C and D). Greater than 90% of the transfected 293 cells were β-galactosidase positive, but <1% of the HM7 cells were β-galactosidase positive. These results indicate that F435-KRAB was not able to suppress the expression of VEGF-A in HM7 cells, because of the extremely poor efficiency of liposome-mediated transfection into HM7 cells.

Figure 1.

Liposome-mediated transfection of plasmids that encode either a ZF-TF or LacZ into HEK 293 cells and HM7 cancer cells. HEK 293T cells (A) and HM7 human cancer cells (B) were transfected with a plasmid that expressed F435-KRAB or the LacZ gene product, β-galactosidase (pcDNA3.1/His/LacZ; Invitrogen) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and the amounts of secreted VEGF-A were measured by ELISA at 2 days after transfection. The F435-KRAB-encoding plasmid efficiently suppressed the expression of VEGF-A in 293T cells, but not in HM7 cells. (C and D) HEK 293T cells and HM7 cells transfected with the LacZ plasmid were stained to visualize the enzyme activity. Greater than 90% of the transfected 293T cells were LacZ positive, but <1% of the HM7 cells were LacZ positive.

Transduction of a VEGF-A-specific transcriptional repressor in vitro

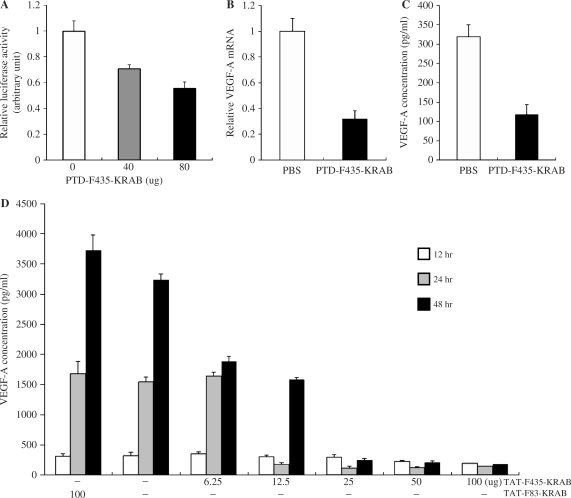

We then tested whether ZF-TFs could be transduced into mammalian cells in vitro. As a first step in generating a transducible TF, we prepared a tripartite fusion protein by joining the F435 ZFP to the C terminus of the 11—amino acid PTD from the HIV-1 Tat protein, and then fusing this construct to the N-terminus of the KRAB domain derived from the human KOX1 protein; the resulting fusion protein was named PTDTat–F435-KRAB. PTDTat–F435-KRAB was expressed in and purified from E. coli, and then added to HEK 293 cells that had been previously transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid in which the luciferase gene was under the control of the VEGF-A promoter. As shown in Figure 2A, the PTDTat–F435-KRAB fusion protein suppressed expression of the luciferase reporter gene in 293 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Purified recombinant F435-KRAB protein that had not been attached to the Tat PTD was used as a control and showed no suppression of luciferase expression (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Regulation of luciferase reporter activity by PTDTAT–F435-KRAB. (A) HEK 293 cells were cotransfected with 15 ng of pGL-VEGF and 68.5 ng of the Renilla luciferase expression plasmid pRL-SV40. The cells were then treated with the indicated amount of purified PTDTAT–F435-KRAB 24 h after transfection. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h after protein transduction. (B) Repression of endogenous VEGF-A at the mRNA level. HEK 293 cells (105 cells/24-well plate) were treated with either PBS or PTDTAT–F435-KRAB (250 μg) for 2 h, then the culture medium was replaced with fresh growth medium (DMEM, 10% FBS). VEGF-A mRNA was analyzed by RT–PCR using specific primers. The amount of VEGF mRNA was normalized to the amount of GAPDH mRNA from the same RT product, then relative VEGF mRNA amounts from PTDTAT–F435-KRAB-treated cells were represented as values compared to normalized values from control PBS-treated cells. (C) From the same experiments described in (B), the culture medium at 24 h after transduction with either PBS (control) or effector (PTDTAT–F435-KRAB) was harvested. The amount of secreted VEGF-A protein was measured by ELISA with an antibody specific to human VEGF-A. (D) Dose-dependent repression of VEGF-A protein expression by PTDTAT–F435-KRAB. HEK293F cells were treated with various amounts of PTDTAT–F435-KRAB for 2 h, and then the culture medium was replaced with fresh growth medium. Culture supernatants were harvested at the indicated times (white bar, after 12 h; gray bar, after 24 and black bar, after 48 h). Secreted VEGF-A amounts were measured by ELISA. TAT-F83-KRAB was used as a negative control. All of the results in Figure 1 are the mean values and SEs of three independent experiments.

Next, we investigated whether the transducible TF was able to downregulate expression of the endogenous VEGF-A gene in HEK 293 cells. The cells were treated with purified PTDTat–F435-KRAB for 3 h, and then incubated for 48 h in fresh culture media. We then harvested the culture supernatants and cells, and analyzed both VEGF-A protein and mRNA concentrations. Treatment of HEK cells with the PTDTat–F435-KRAB fusion protein reduced VEGF-A mRNA concentrations 3.1-fold (i.e. 68% suppression), compared to PBS-treated control cells (Figure 2B). VEGF-A protein production was also decreased by 2.7-fold (63% suppression) in the culture treated with PTDTat–F435-KRAB, relative to the control culture (Figure 2C).

PTDTat–F435-KRAB also effectively suppressed the expression of VEGF-A in cancer cells. VEGF-A protein concentrations in the human colorectal cancer HM7 cell line are several fold higher than those in the noncancerous 293 cells. HM7 cells were treated with varying amounts of PTDTat–F435-KRAB, and VEGF-A protein concentrations were measured at various time points after addition of the transducible protein to the culture media. We observed strong dose-dependent inhibition of VEGF-A production by PTDTat–F435-KRAB (Figure 2D). No significant decrease in the VEGF-A protein concentrations were observed at 12 h after treatment of the HM7 cells with PTDTat–F435-KRAB. However, the transducible protein yielded efficient (up to 18-fold) suppression of VEGF-A production after 24 and 48 h of incubation. In contrast, PTDTat–F83-KRAB, which was used as a negative control, failed to suppress the expression of VEGF-A by the cancer cells (Figure 2D). The F83 protein is a ZFP designed to recognize the human VEGF-A promoter and binds tightly to its target site in vitro. However, F83 is unable to regulate expression of the endogenous VEGF-A gene (24).

Inhibition of tumor growth in vivo by the transducible transcriptional repressor PTDTat–F435-KRAB

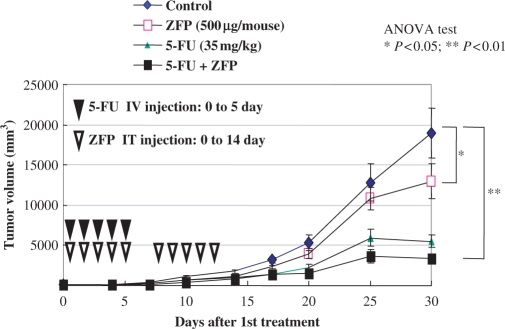

We next investigated whether the VEGF-A-specific PTDTat–F435-KRAB fusion protein could inhibit the formation of new blood vessels around tumor cells and retard the growth rate of tumor cells in vivo. HM7 cells were injected into the dorsal sacs of nude mice (BALB/c) and allowed to grow for 7 days. The animals were then divided into the following four treatment groups: group 1, treatment with PTDTat–F435-KRAB alone [10 daily intratumoral (IT) injections]; group 2, treatment with 5-FU (an antineoplastic drug) alone (5 daily IT injections); group 3, treatment with PTDTat–F435-KRAB and 5-FU (5 daily IT injections with PTDTat–F435-KRAB and 5-FU, followed by 5 daily IT injections with PBS) and group 4, treatment with PBS (control) (10 daily IT injections).

Tumors injected with PTDTat–F435-KRAB alone showed a significant reduction in size compared to PBS-treated control tumors (Figure 3). The VEGF-targeting protein showed 34 and 27% reduction in the average tumor volume compared to control at days 14 and 17, respectively, after the first injection (P < 0.05). Similarly, at day 30, the average tumor volume of the protein—treated mice was only 67% of that of PBS-treated mice (P < 0.05). Thus, the transducible TF alone inhibited tumor growth by 33% at day 30. 5-FU alone strongly inhibited tumor growth by 70% compared to the PBS-treated control group. The combination treatment of both 5-FU and PTDTat–F435-KRAB led to an 83% reduction in tumor size, relative to the PBS-treated control group. [However, the difference between the antitumor effect of 5-FU treatment and that of the combination treatment was not statistically significant (P = 0.058).] These results suggest that the VEGF-A targeting, synthetic transducible TF functions as an antitumor agent and may enhance the response of tumor cells to 5-FU treatment.

Figure 3.

Tumor growth inhibition in xenograft mice. Human colorectal cancer cells (HM7 cell line) were xenografted into nude mice. The mice either received no treatment (control) or were treated by injection with PTDTAT–F435-KRAB (ZFP) alone; 5-FU in combination with PTDTAT–F435-KRAB (ZFP + 5-FU) or 5-FU alone at the indicated dose and injection time (see Materials and methods section). Tumor volumes were assessed for 30 days after the first injection of the various substances. All data are presented as means and SEMs. IV, intravenous; IT, intratumoral.

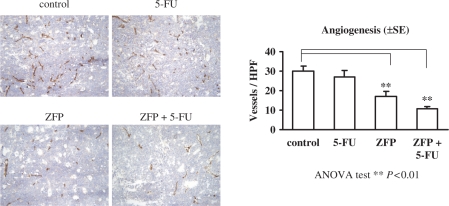

To confirm the mechanism of the antitumor activity of PTDTat–F435-KRAB, we carried out immunohistochemical analyses. After the mice were sacrificed, the tumors were removed and bisected. Blood vessels were visualized by staining tumor cryosections with a monoclonal rat antimouse CD31 antibody. As shown in Figure 4, both the number and size of CD31-positive blood vessels were decreased significantly (43%) in tumor sections from mice treated with PTDTat–F435-KRAB, relative to PBS controls. 5-FU treatment alone did not elicit a reduction of CD31-positive vessels. 5-FU is a potent inhibitor of thymidylate synthase and does not inhibit angiogenesis. The small reduction of CD31-positive vessels in animals treated with 5-FU in our results is statistically insignificant. In contrast, the combination treatment of 5-FU and PTDTat–F435-KRAB strongly inhibited the formation of blood vessels; microvessel density was reduced by 64% in response to the combination treatment, compared to the PBS control group (P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of tumor blood vessels. Cryosections of tumors from xenografted mice described in Figure 2 were stained to visualize CD31 (PECAM-1). Angiogenesis indices were determined by calculating vessel densities from at least three cryosections prepared from mice of each group. The differences between the angiogenesis index of tumors from control (PBS-treated) mice and the angiogenesis indices of tumors from mice treated with PTDTAT–F435-KRAB (ZFP) or PTDTAT–F435-KRAB and 5-FU (ZFP + 5-FU) were statistically significant (++) (ANOVA test, P < 0.01). The angiogenesis indices shown are the mean values and SE of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Artificial TFs constructed by assembling ZF DNA-binding modules and appropriate transcriptional effector domains have been developed for the regulation of a variety of viral and endogenous mammalian genes (12,14–22,24). In these studies, ZF-TFs of choice have been delivered to target cells via DNA transfection or viral vectors, methods that have limitations for use in research and medicine. The DNA delivery efficiency of liposome-mediated transfection is highly dependent on cell types and usually very low in primary cultures and certain tumor cells (10,11). Naked DNA transfection, while inefficient, is often used in animal experiments and clinical studies in humans, largely because of its favorable safety profile (25). Safety concerns also make the use of viral vectors in clinical trials difficult, if not impossible. PT is an alternative method with a few important advantages. Various peptide tags and protein domains have been developed as carriers of cargo proteins to their desired locations in the cell. The Tat-derived PT peptide used in this study has been shown to be highly efficient for the delivery of diverse proteins into mammalian cells both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, the precise dose of transducible proteins is more readily determined, compared to viral delivery or DNA transfection. Indeed, it is usually quite difficult to control the concentration of effective proteins expressed in cells when the proteins are introduced via DNA transfection or viral delivery.

In this study, we employed the well-characterized 11 amino acid PTD derived from the HIV-1 Tat transcriptional activator to produce transducible TFs for targeted regulation of an endogenous human gene. The efficiency of PTD-mediated protein delivery is highly dependent on many factors, including but not limited to, cargo proteins, target cells and the PTD itself (4). Tachikawa et al(26) showed that artificial transcription factors fused to the Tat-derived PTD were efficiently delivered into mammalian cells in vitro. To the best of our knowledge, the study described herein is the first report in which artificial TFs were transduced into mammalian cells in vivo. Although many ZF-TFs have been designed to target specifically various mammalian genes, only one factor has been tested in animal studies thus far. Rebar et al(16) reported that ZF transcriptional activators that target the VEGF-A gene are able to elicit blood vessel formation in rodent models, when delivered via naked DNA transfection or viral vectors. An expression plasmid encoding this VEGF-A transcriptional activator is now being tested in clinical studies in the US for the treatment of cardiovascular disease (27). Here, we report on a second ZF-TF whose efficacy has been demonstrated in animal models. Our ZF-TF downregulated the expression of VEGF-A and functioned as an anticancer agent in mouse xenograft experiments.

Unlike the ZF-TFs described in this report, the artificial TFs used by others were constructed by introducing mutations at key positions in given framework sequences of ZFPs. These mutations are likely to lead to the production of proteins that induces an immune response, especially when the proteins are tranduced in vivo. Our ZF-TFs contain naturally occurring ZFs derived from sequences in the human genome and thus are less likely to elicit an immune response (24). The use of a PTD derived from a human protein (6) instead of the viral Tat PTD to make transducible TFs would also help to minimize the host immune response.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (R01-2006-000-10084-0, R15-2004-024-02001-0 and M10416130002-04N1613-00210 to C.-O.Y.; R17-2007-019-01001-0 to J.-S.K.). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by SNU.

Conflict of interest statement. JSK holds stock in Toolgen, Inc. JSK is currently conducting research sponsored by the company.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nagahara H, Vocero-Akbani AM, Snyder EL, Ho A, Latham DG, Lissy NA, Becker-Hapak M, Ezhevsky SA, Dowdy SF. Transduction of full-length TAT fusion proteins into mammalian cells: TAT-p27Kip1 induces cell migration. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1449–1452. doi: 10.1038/4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarze SR, Ho A, Vocero-Akbani A, Dowdy SF. In vivo protein transduction: delivery of a biologically active protein into the mouse. Science. 1999;285:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwarze SR, Hruska KA, Dowdy SF. Protein transduction: unrestricted delivery into all cells? Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:290–295. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01771-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. Protein transduction technology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002;13:52–56. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia H, Mao Q, Davidson BL. The HIV Tat protein transduction domain improves the biodistribution of beta-glucuronidase expressed from recombinant viral vectors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:640–644. doi: 10.1038/90242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Coupade C, Fittipaldi A, Chagnas V, Michel M, Carlier S, Tasciotti E, Darmon A, Ravel D, Kearsey J, Giacca M, et al. Novel human-derived cell-penetrating peptides for specific subcellular delivery of therapeutic biomolecules. Biochem. J. 2005;390:407–418. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon YD, Oh SK, Kim HS, Ku SY, Kim SH, Choi YM, Moon SY. Cellular manipulation of human embryonic stem cells by TAT-PDX1 protein transduction. Mol. Ther. 2005;12:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H, Ryu J, Kim KA, Lee KS, Lee JY, Park JB, Park J, Choi SY. Transduction of yeast cytosine deaminase mediated by HIV-1 Tat basic domain into tumor cells induces chemosensitivity to 5-fluorocytosine. Exp. Mol. Med. 2004;36:43–51. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vocero-Akbani AM, Heyden NV, Lissy NA, Ratner L, Dowdy SF. Killing HIV-infected cells by transduction with an HIV protease-activated caspase-3 protein. Nat. Med. 1999;5:29–33. doi: 10.1038/4710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamm A, Krott N, Breibach I, Blindt R, Bosserhoff AK. Efficient transfection method for primary cells. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:235–245. doi: 10.1089/107632702753725003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cemazar M, Sersa G, Wilson J, Tozer GM, Hart SL, Grosel A, Dachs GU. Effective gene transfer to solid tumors using different nonviral gene delivery techniques: electroporation, liposomes, and integrin-targeted vector. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:399–406. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beerli RR, Dreier B, Barbas CF. Positive and negative regulation of endogenous genes by designed transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1495–1500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040552697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang JS, Kim JS. Zinc finger proteins as designer transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:8742–8748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon HS, Shin HC, Kim JS. Suppression of vascular endothelial growth factor expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon RJ, Kim SK, Lee SI, Hwang SJ, Lee GM, Kim J.-S, Seol W. Artificial transcription factors increase production of recombinant antibodies in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnol. Lett. 2006;28:9–15. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-4680-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rebar EJ, Huang Y, Hickey R, Nath AK, Meoli D, Nath S, Chen B, Xu L, Liang Y, Jamieson AC, et al. Induction of angiogenesis in a mouse model using engineered transcription factors. Nat. Med. 2002;8:1427–1432. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren D, Collingwood TN, Rebar EJ, Wolffe AP, Camp HS. PPARgamma knockdown by engineered transcription factors: exogenous PPARgamma2 but not PPARgamma1 reactivates adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:27–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.953802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds L, Ullman C, Moore M, Isalan M, West MJ, Clapham P, Klug A, Choo Y. Repression of the HIV-1 5′ LTR promoter and inhibition of HIV-1 replication by using engineered zinc-finger transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1615–1620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252770699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snowden AW, Zhang L, Urnov F, Dent C, Jouvenot Y, Zhong X, Rebar EJ, Jamieson AC, Zhang HS, Tan S, et al. Repression of vascular endothelial growth factor A in glioblastoma cells using engineered zinc finger transcription factors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8968–8976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan S, Guschin D, Davalos A, Lee YL, Snowden AW, Jouvenot Y, Zhang HS, Howes K, McNamara AR, Lai A, et al. Zinc-finger protein-targeted gene regulation: genomewide single-gene specificity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11997–12002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2035056100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L. Synthetic zinc finger transcription factor action at an endogenous chromosomal site. Activation of the human erythropoietin gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33850–33860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segal DJ, Goncalves J, Eberhardy S, Swan CH, Torbett BE, Li X, Barbas C.F., III Attenuation of HIV-1 replication in primary human cells with a designed zinc finger transcription factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:14509–14519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon WH, Jung YJ, Kim TD, Li G, Park BJ, Kim JY, Lee YC, Kim JM, Park JI, Park HD, et al. Gabexate mesilate inhibits colon cancer growth, invasion, and metastasis by reducing matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:4517–4526. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bae KH, Kwon YD, Shin HC, Hwang MS, Ryu EH, Park KS, Yang HY, Lee DK, Lee Y, Park J, et al. Human zinc fingers as building blocks in the construction of artificial transcription factors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff JA, Budker V. The mechanism of naked DNA uptake and expression. Adv. Genet. 2005;54:3–20. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(05)54001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tachikawa K, Schroder O, Frey G, Briggs SP, Sera T. Regulation of the endogenous VEGF-A gene by exogenous designed regulatory proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15225–15230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406473101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rebar EJ. Development of pro-angiogenic engineered transcription factors for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2004;13:829–839. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.7.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]