Abstract

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) system is altered in post-mortem brains of individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD), but the functional relevance of this observation remains to be elucidated. To this end, we tested whether administering agents that act on FGF receptors would have antidepressant-like effects in rodents. We microinjected either FGF2 (200ng, i.c.v.) or the FG loop (FGL) of neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) (5μg, i.c.v.) into the lateral ventricle of rats and tested them on the forced swim test. Activating FGF receptors acutely had an antidepressant-like effect in the forced swim test. Furthermore, chronic FGF2 decreased depression-like behavior as assessed by two independent tests. Finally, the FGF system itself was altered after FGF2 administration. Specifically, there was an increase in FGFR1 mRNA in the dentate gyrus 24 h post FGF2, suggesting the potential for self-amplification of the initial signal. These results support the potential therapeutic use of FGF2 or related molecules in the treatment of MDD and point to alternate mechanisms of neuronal remodeling that may be critical in this treatment.

Keywords: Depression, Neurotrophin, Hippocampus, NCAM, Acute, Chronic

1. INTRODUCTION

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family has been shown to be dysregulated in post-mortem studies of individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD). Specifically, several ligands (i.e. FGF1, FGF2) and receptors (i.e. FGFR2, FGFR3) were downregulated in the anterior cingulate and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Evans et al., 2004a). More recent studies have also extended these findings to the hippocampus (Evans et al., 2004b), pointing to an overall ‘net decrease’ in the tone of the FGF system in MDD. Whether the FGF system dysregulation is primary to MDD and leads to the disease process or whether it is secondary to it remains unclear. However, it is important to ask whether the change in FGF system expression is likely to have functional relevance in depression, which requires the use of animal models.

The FGF receptors are tyrosine kinase receptors that dimerize and autophosphorylate after binding of two FGF2 molecules bound with heparin. The receptors contain three Ig-like domains (D1, D2 and D3). Much of the ligand binding properties are conferred by D2 and D3. Furthermore, the binding parameters of neural cell adhesion molecule to FGF receptors have been reasonably well described (Christensen et al., 2006; Kiselyov et al., 2005; Williams et al., 1994). A recent review of the FGF system highlights the functions of the various FGF ligands and receptors (Turner et al., 2006).

FGF2 appears responsive to treatment with various psychoactive drugs. Thus, the protein is increased in the hippocampus after treatment with the anxiolytic diazepam (Gomez-Pinilla et al., 2000). Perhaps most relevant to this study, chronic administration of several antidepressants resulted in an increase in FGF2 in hippocampal and cortical areas (Mallei et al., 2002).

Literature on the role of the FGF system in animal models of depression is lacking. However, another neurotrophin, BDNF, has been found to exert antidepressant-like effects acutely (Nestler and Carlezon, 2006; Shirayama et al., 2002). Recent studies with transgenic mice overexpressing BDNF also support the antidepressant-like properties of BDNF (Govindarajan et al., 2006). Similarly, BDNF knockout mice show an increase in antidepressant-like behavior in females and an overall resistance to antidepressant treatment (Monteggia et al., 2007). Moreover, chronic antidepressants increase levels of BDNF in cortical and hippocampal areas (Russo-Neustadt et al., 1999), and this increase in growth factor levels has been thought to be critical to the mode of action of these drugs.

Interestingly, social defeat has been suggested as an animal model of depression (Kollack-Walker et al., 1997) and appears associated with altered levels of BDNF (Berton et al., 2006). We have also observed FGF system alterations following social defeat (Turner et al., 2007). Given the clinical evidence of decreased levels of FGF2 in the brains of depressed individuals and its apparent modulation by a history of antidepressants (Evans et al, 2004a; Mallei et al., 2002), it is reasonable to hypothesize that FGF2 may prove to have antidepressant properties—a hypothesis being tested in this report.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether acute FGF2 administration can modulate affective responsiveness in a rodent test used to screen for antidepressant effects-the Porsolt Swim Test. We tested another molecule that acts on FGF receptors and is expected to mimic the effects of FGF2, the F and G β strands and interconnecting loop region of NCAM’s second fibronectin type 3 module (FGL) (Kiselyov et al., 2003). We also assessed the effects of chronic FGF2 administration on depression-like behavior in two different paradigms. Finally, we determined whether FGF2 administration alters the levels of either the endogenous ligand (i.e. FGF2 itself) or one of its receptors (i.e. FGFR1).

2. RESULTS

Acute Microinjection Studies

In the forced swim test, the FGF2-injected (n=12) animals exhibited significantly more swimming [t(23) = 2.20, p<0.05] and less immobility [t(23) = 2.88, p<0.01] than controls (n=13), see Figure 1A. This is indicative of less depression-like behavior in FGF2 animals. In a separate experiment, the FGL-injected animals (n=13) exhibited significantly less immobility [t(24) = 2.13, p < 0.05] than controls (n=13), see Figure 1B. Again, this is indicative of less depression-like behavior. These results are also in the same direction as the FGF2 data consistent with the fact that both molecules stimulate FGF receptors.

Figure 1. Acute microinjections of FGF2 and FGL alter depression-like behavior.

(a) Effect of FGF2 microinjections on depression-like behavior in the forced swim test. *p < .05; **p < .01 (b) Effect of FGL microinjections on depression-like behavior in the forced swim test. *p < .05

Chronic FGF2 Microinjection

In the forced swim test, the FGF2 animals (n=10) exhibited significantly less immobility [t(19) = 2.70, p < 0.05] and significantly more swimming [T(10,11) = 149, p < 0.01] than vehicle (n=11) animals, see Figure 2A. However, climbing was not significantly different between the groups [t(19) = -0.02, p = 0.98]. Novelty-suppressed feeding, a marker of chronic antidepressant effects, was altered between FGF2 (n=9) and vehicle (n=11) animals. Here, the FGF2 animals exhibited a significant decrease in latency to feed [t(18) = 2.17, p < 0.05], see Figure 2B. However, chronic administration of FGF2 did not alter locomotor activity [t(17) = 0.66, p = 0.52] between FGF2 (n=8) and vehicle (n=11) animals, see Figure 2C. Together these results suggest that chronic FGF2 can have antidepressant-like effects without altering locomotor activity.

Figure 2. Chronic microinjections of FGF2 decreased depression-like behavior.

(a) Effect of chronic FGF2 microinjections on depression-like behavior in the forced swim test. *p < .05; **p < .01 (b) Effect of chronic FGF2 microinjections on latency to feed in the novelty-suppressed feeding test. *p < .05 (c) Effect of chronic FGF2 microinjections on locomotor activity.

FGF2 and FGFR1 mRNA In Situ Hybridization

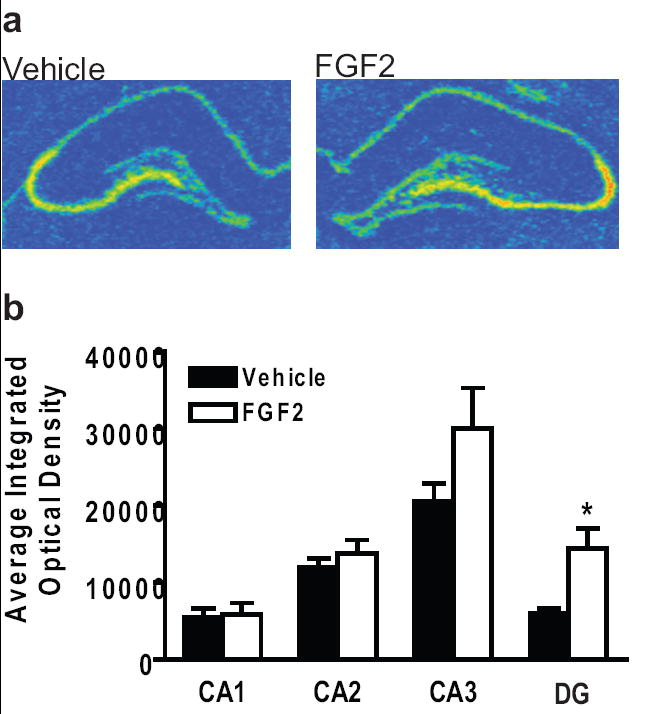

Figure 3A is an illustration of FGFR1 expression levels in the hippocampus after vehicle or FGF2. Twenty-four hours after treatment, the FGF2-injected animals exhibited significantly higher levels of FGFR1 mRNA in the dentate gyrus than the vehicle-injected animals [t(8) = -3.25, p < 0.05], see Figure 3B. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in any other areas of the hippocampus for FGFR1. There were also no significant differences in the expression of FGF2 in the hippocampus between the two groups (see Table 1).

Figure 3. FGFR1 mRNA was increased in the dentate gyrus 24 h after FGF2 microinjection.

(a) Representative FGFR1 mRNA levels in the hippocampus of vehicle (left) and FGF2 (right) animals 24 h after microinjection of FGF2. Red color denotes high level of expression. (b) Average integrated optical density values of FGFR1 mRNA expression for vehicle and FGF2 animals in the hippocampus. *p < .05

Table 1.

Average integrated optical density values of FGF2 mRNA by in situ hybridization in the hippocampus.

| Region | n | Vehicle ± s.e.m. | n | FGF2 ± s.e.m. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA1 | 5 | 2225 ± 451 | 5 | 1997 ± 619 |

| CA2 | 5 | 17458 ± 2037 | 5 | 21509 ± 2849 |

| CA3 | 5 | 1574 ± 327 | 5 | 1568 ± 431 |

| DG | 5 | 3203 + 696 | 5 | 2852 ± 521 |

3. DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate the following: 1) Both acute and chronic administration of FGF2 has antidepressant-like effects; 2) Acute administration of FGL can also have antidepressant-like effects; 3) The antidepressant-like effect of acute FGF2 treatment was observed with a specific increase in FGFR1 mRNA in the dentate gyrus.

Acute FGF2 decreased immobility in the forced swim test and increased swimming behavior. These findings are also similar to the acute antidepressant-like effects observed with BDNF (Shirayama et al., 2002). Chronic FGF2 was also effective in decreasing depression-like behavior. The depression tests utilized are sensitive to numerous antidepressants, as well as FGF-related treatments. Additional experiments should be performed following the chronic treatment, as it is possible that performing behavioral testing during the chronic treatment may have confounded the results.

Although the dendrimer of FGL is more potent than the monomer, the cell adhesion molecules function to promote cell migration, neurite outgrowth, synaptic plasticity, and maintain synaptic structures (Doherty et al., 2000; Kiselyov et al., 2005). Previously, FGL has been shown to improve learning and memory in a spatial memory task (Cambon et al., 2004). This same loop has also been shown to be neuroprotective in ischemia models and enhance social memory retention (Secher et al., 2006; Skibo et al., 2005). In this study, acute administration of FGL resulted in a significant decrease in immobility in the forced swim test. This effect is consistent with the above findings for FGF2. Chronic microinjection studies should be performed for FGL to further define its role in depression-like behavior.

FGL mimics NCAM activation of FGF receptors. Interestingly, NCAM-deficient mice exhibit increased depression-like behavior (Conboy et al., 2008). This is consistent with our findings that FGL decreased depression-like behavior and suggests that FGL may be a potential treatment for MDD. In further support of this notion, a recent review summarizes the role of NCAM in mood disorders (Sandi and Bisaz, 2007).

FGL differs from FGF2 in activation of FGF receptors. Although both FGF2 and FGL activate similar intracellular signaling cascades, FGL has a weaker effect. Thus, convergence at the intracellular level is necessary to regulate the cytoskeleton and for synapse formation. NCAM’s fibronectin 3 modules 1-2 bind to FGF receptor Ig modules 2-3. This, in effect, allows for calcium entry into the cell and downstream activation of signaling cascades (for review see Hinsby et al., 2004; Kiryushko et al., 2004).

Finally, FGF2 was accompanied by an increase in FGFR1 levels, specifically in the dentate gyrus 24 h after treatment. The mechanism for this rapid receptor regulation needs further investigation. However, levels of another neurotrophin receptor, trkB, are known to exhibit a circadian rhythm in the dentate gyrus, suggesting complex acute regulatory mechanisms (Dolci et al., 2003). Furthermore, BDNF levels have been shown to change rapidly following immobilization stress (Marmigere et al., 2003).

In summary, convergent evidence suggests an important role of the FGF family in the regulation of depressive behavior. This includes findings of significant dysregulation in this system in postmortem brains of human subjects with a history of major depression. It also includes the present evidence demonstrating that agonists of FGF receptors, i.e. FGF2 or FGL, have antidepressant-like effects. As importantly, the system may have an acute self-amplifying effect—i.e. FGF2 exposure induces the expression of one of its own receptors. Although the time course and mechanism(s) responsible for these effects remains to be elucidated, the FGF family emerges as an interesting and novel target for the modulation or treatment of major depression.

4. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (220-250g; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA.) were housed under a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. Animals were allowed to acclimate to the housing conditions for 7 days prior to any experiments. Animals were housed two per cage until surgery and then were singly housed after surgery. All animals were treated in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines on laboratory animal use and care and in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC).

Acute Microinjections

Rats were anesthetized using isoflurane and guide cannulae (22-gauge, Plastics One Inc., VA. USA) were implanted into the left lateral ventricle (coordinates from bregma: AP -1.1; ML +1.3; DV -3.0) using a small animal stereotaxic apparatus. The guide cannula was anchored to the skull and fitted with an obdurator. Five days after surgery, the obdurators were removed and a 28-gauge injector cannula was inserted extending 1.5mm below the tip of the guides. The microinjection cannula was connected by PE-20 tubing to a Hamilton syringe mounted on a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, MA. USA). Rats were microinjected with either recombinant human FGF2 (200ng, Sigma) or FGL peptide (EVYVVAENQQGKSKA; 5μg, synthesized at University of Michigan) dissolved in artificial extracellular fluid (aECF) with the addition of 100μg/ml bovine serum albumin (Cambon et al., 2004; Kuhn et al., 1997; Williams et al., 2001).

The rationale for the FGF2 dose was based on a dose that chronically stimulated neurogenesis in the subventricular zone (Kuhn et al., 1997). Similarly, the dose of the FGL peptide that was used was based on a dose that enhanced fear conditioning and spatial learning (Cambon et al., 2004). The FGL peptide is known to be involved in the binding of NCAM to FGF receptors. Although NCAM has only been crystallized in binding to FGFR1 and FGFR2, it is likely that NCAM interacts with all of the FGF receptors (Christensen et al., 2006; Kiselyov et al., 2005).

Total volumes were infused (FGF2: 8μl; FGL: 5μl) in freely moving animals at 1.0μl/min, and the injector was left in place for an additional 5 min to allow for diffusion. Animals were then subjected to behavioral testing. After testing, the rats were killed by decapitation and the brains were snap frozen in isopentane. A subset of animals was sacrificed 24 hrs after the microinjections and brains processed for mRNA in situ hybridizations. The brains were sliced and cresyl violet staining was performed to verify the placement of the microinjection cannulae.

Forced Swim Test

Animals were placed in cylinders filled with water (25°C) so that the rat’s tail could not touch the bottom of the cylinder. Day One consisted of a 15-minute session, immediately after which the animals were microinjected, and Day Two (24-h post-injection for the acute study) consisted of the 5-minute test. The twenty-four hour time point was chosen due to the half-life of FGF2 in the cerebrospinal fluid (Wagner et al., 1999). After testing, rats were dried and returned to their home cages. Behaviors were monitored from above by a video camera and subsequently scored by an observer blind to experimental condition as described by (Lucki, 1997). Swimming consisted of horizontal movement in the swim chamber. Climbing consisted of a vertically-directed movement with the forepaws typically above water along the walls of the swim chamber. Immobility was defined as the minimal movement necessary to keep the head above water level. Percent total duration of swimming, climbing and immobility episodes was scored using The Observer software (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands).

Chronic FGF2

Rats were administered FGF2 (200ng, i.c.v.) or vehicle (aECF, i.c.v.) daily for a total of 18 days between 8:00 AM and 10:00 AM. Rats were tested for locomotor activity (Day 18), and in the forced swim (Days 15 and 16) and novelty-suppressed feeding paradigms (Day 17). The rats were tested between 1:00 PM and 4:00 PM with each test separated by 24 hours (Mineur et al., 2007).

Novelty-Suppressed Feeding

Food was removed from the cage twenty-four hours prior to testing in an open-field apparatus (100 × 100 × 50 cm) under dim light. The floor was black Plexiglas and the sides were clear Plexiglas made opaque by the addition of white paint. A small piece of rat chow was placed in the center of the arena and the latency to the first feeding was recorded in seconds. Each animal started in a corner of the arena and was allowed a maximum of 5 min to begin feeding. After testing, the animals were returned to their home cage with food and water available ad libitum. One animal was omitted from the study prior to testing due to an unhealthy appearance.

Locomotor Activity

Rats were tested in a locomotion apparatus for 1 h following chronic microinjections of vehicle or FGF2. The environment consisted of a 43 × 21.5 × 25.5 cm acrylic cage with stainless steel grid flooring. Horizontal and vertical movement was monitored by photocell beam breaks for a one-hour period. Horizontal and vertical movement was added together for a measure of total locomotor activity for each animal and an average was calculated for each animal and group. One animal was omitted due to a malfunctioning locomotor chamber.

FGF2 and FGFR1 mRNA In Situ Hybridization

Tissue was sectioned at -20°C at 10μm (n=5/group) and sliced in series throughout the hippocampus, mounted on SuperFrost Plus slides (FisherScientific) and stored at -80°C until processed. The hippocampus was chosen for analysis since other antidepressants are known to increase both neurogenesis and growth factors, such as FGF2, in this region (Mallei et al., 2002; Berton & Nestler, 2006; (Sairanen et al., 2005). The hippocampus exhibits a high level of FGF2 and FGFR1 gene expression, and we have observed post-mortem alterations in MDD of the FGF system in the hippocampus. In situ hybridization methodology has been previously described elsewhere (Kabbaj et al., 2000). Sections were taken every 200μm. The sequences of rat mRNA used for generating probes of genes are complementary to the following RefSeq database nos. FGF2 (NM019305, 716-994); FGFR1 (NM024146, 320-977). All probes were synthesized in our laboratory. Exposure times were experimentally determined for each probe to maximize signal and are as follows: FGF2 (7 days) and FGFR1 (7 days). After appropriate exposure times, the films were developed (Kodak D-19; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA). Brain section images were captured from film with a CCD camera (TM-745, Pulnix) using MCID. Radioactive signals were quantified using computer-assisted optical densitometry software (Scion Image). Optical densities were found by outlining the region of interest from both hemispheres throughout the dorsal hippocampus. Optical density measurements were corrected for background, and the signal threshold was defined as the mean gray value of background plus 3.5X its standard deviation. Only pixels with gray values exceeding the above-defined threshold were included in the analysis. Data from multiple sections per animal were averaged resulting in a mean integrated optical density value for each animal and then averaged for each group.

Statistical Analyses

All studies were analyzed by a Student’s t-test or Mann Whitney Rank Sum test when normality failed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Sharon Burke, James Stewart and Jennifer Fitzpatrick for their technical assistance and expertise. This work was supported by the Pritzker Neuropsychiatric Disorders Research Consortium, NIH Conte center grant #MH060398, NIMH Program Project Grant #MH042251, NIDA Program Project Grant #DA021633 and NIDA Training Grants #DA007268 and #DA007267.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST CAT, LPT, SJW and HA are members of the Pritzker Neuropsychiatric Disorders Research Consortium, which is supported by the Pritzker Neuropsychiatric Disorders Research Fund L.L.C. A shared intellectual property agreement exists between this philanthropic fund and the University of Michigan, the University of California, Stanford University and Cornell University to encourage the development of appropriate findings for research and clinical applications. ELG does not have any conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berton O, McClung CA, Dileone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Graham D, Tsankova NM, Bolanos CA, Rios M, Monteggia LM, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science. 2006;311:864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1120972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambon K, Hansen SM, Venero C, Herrero AI, Skibo G, Berezin V, Bock E, Sandi C. A synthetic neural cell adhesion molecule mimetic peptide promotes synaptogenesis, enhances presynaptic function, and facilitates memory consolidation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4197–4204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0436-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen C, Lauridsen JB, Berezin V, Bock E, Kiselyov VV. The neural cell adhesion molecule binds to fibroblast growth factor receptor 2. FEBS Letters. 2006;580:3386–3390. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy L, Bisaz R, Markram K, Sandi C. Role of NCAM in Emotion and Learning. Neurochem Res. 2008 doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1170-4_18. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty P, Williams G, Williams EJ. CAMs and axonal growth: a critical evaluation of the role of calcium and the MAPK cascade. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:283–295. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolci C, Montaruli A, Roveda E, Barajon I, Vizzotto L, Grassi Zucconi G, Carandente F. Circadian variations in expression of the trkB receptor in adult rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2003;994:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SJ, Choudary PV, Neal CR, Li JZ, Vawter MP, Tomita H, Lopez JF, Thompson RC, Meng F, Stead JD, Walsh DM, Myers RM, Bunney WE, Watson SJ, Jones EG, Akil H. Dysregulation of the fibroblast growth factor system in major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004a;101:15506–15511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406788101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SJ, Li J, Choudary PV, Tomita H, Vawter MP, Turner CA, Lopez JF, Thompson RC, Meng F, Bolstad BM, Speed TP, Myers RM, Bunney WE, Jones EG, Watson SJ, Akil H. Society for Neuroscience. 2004b. Dysregulation of growth factor system gene expression in limbic structures of subjects with major depressive disorder. Vol. Program No. 114.10, eds. 2004 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner Online, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Pinilla F, Dao L, Choi J, Ryba EA. Diazepam induces FGF-2 mRNA in the hippocampus and striatum. Brain Res Bull. 2000;53:283–289. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan A, Rao BS, Nair D, Trinh M, Mawjee N, Tonegawa S, Chattarji S. Transgenic brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression causes both anxiogenic and antidepressant effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13208–13213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605180103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsby AM, Lundfald L, Ditlevsen DK, Korshunova I, Juhl L, Meakin SO, Berezin V, Bock E. ShcA regulates neurite outgrowth stimulated by neural cell adhesion molecule but not by fibroblast growth factor 2: evidence for a distinct fibroblast growth factor receptor response to neural cell adhesion molecule activation. J Neurochem. 2004;91:694–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbaj M, Devine DP, Savage VR, Akil H. Neurobiological correlates of individual differences in novelty-seeking behavior in the rat: differential expression of stress-related molecules. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6983–6988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06983.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiryushko D, Berezin V, Bock E. Regulators of neurite outgrowth: role of cell adhesion molecules. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1014:140–154. doi: 10.1196/annals.1294.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselyov VV, Skladchikova G, Hinsby AM, Jensen PH, Kulahin N, Soroka V, Pedersen N, Tsetlin V, Poulsen FM, Berezin V, Bock E. Structural basis for a direct interaction between FGFR1 and NCAM and evidence for a regulatory role of ATP. Structure. 2003;11:691–701. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselyov VV, Soroka V, Berezin V, Bock E. Structural biology of NCAM homophilic binding and activation of FGFR. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1169–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollack-Walker S, Watson SJ, Akil H. Social stress in hamsters: defeat activates specific neurocircuits within the brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8842–8855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-22-08842.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn HG, Winkler J, Kempermann G, Thal LJ, Gage FH. Epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2 have different effects on neural progenitors in the adult rat brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5820–5829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucki I. The forced swimming test as a model for core and component behavioral effects of antidepressant drugs. Behav Pharmacol. 1997;8:523–532. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199711000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallei A, Shi B, Mocchetti I. Antidepressant treatments induce the expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in cortical and hippocampal neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:1017–1024. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.5.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmigere F, Givalois L, Rage F, Arancibia S, Tapia-Arancibia L. Rapid induction of BDNF expression in the hippocampus during immobilization stress challenge in adult rats. Hippocampus. 2003;13:646–655. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineur YS, Picciotto MR, Sanacora G. Antidepressant-like effects of ceftriaxone in male C57BL/6J mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:250–252. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteggia LM, Luikart B, Barrot M, Theobold D, Malkovska I, Nef S, Parada LF, Nestler EJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor conditional knockouts show gender differences in depression-related behaviors. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo-Neustadt A, Beard RC, Cotman CW. Exercise, antidepressant medications, and enhanced brain derived neurotrophic factor expression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:679–682. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen M, Lucas G, Ernfors P, Castren M, Castren E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and antidepressant drugs have different but coordinated effects on neuronal turnover, proliferation, and survival in the adult dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1089–1094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3741-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandi C, Bisaz R. A model for the involvement of neural cell adhesion molecules in stress-related mood disorders. Neuroendocrinology. 2007;85:158–176. doi: 10.1159/000101535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secher T, Novitskaia V, Berezin V, Bock E, Glenthoj B, Klementiev B. A neural cell adhesion molecule-derived fibroblast growth factor receptor agonist, the FGL-peptide, promotes early postnatal sensorimotor development and enhances social memory retention. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1289–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama Y, Chen AC, Nakagawa S, Russell DS, Duman RS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor produces antidepressant effects in behavioral models of depression. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3251–3261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03251.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibo GG, Lushnikova IV, Voronin KY, Dmitrieva O, Novikova T, Klementiev B, Vaudano E, Berezin VA, Bock E. A synthetic NCAM-derived peptide, FGL, protects hippocampal neurons from ischemic insult both in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1589–1596. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CA, Akil H, Watson SJ, Evans SJ. The fibroblast growth factor system and mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1128–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CA, Calvo N, Frost DO, Akil H, Watson SJ. The fibroblast growth factor system is downregulated following social defeat. Neurosci Lett. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JP, Black IB, DiCicco-Bloom E. Stimulation of neonatal and adult brain neurogenesis by subcutaneous injection of basic fibroblast growth factor. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6006–6016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06006.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EJ, Furness J, Walsh FS, Doherty P. Activation of the FGF receptor underlies neurite outgrowth stimulated by L1, N-CAM, and N-cadherin. Neuron. 1994;13:583–594. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]