Abstract

The capacity of dendritic cells (DCs) to migrate from peripheral organs to lymph nodes (LNs) is important in the initiation of a T cell–mediated immune response. The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters P-glycoprotein (P-gp; ABCB1) and the multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1; ABCC1) have been shown to play a role in both human and murine DC migration. Here we show that a more recently discovered family member, MRP4 (ABCC4), is expressed on both epidermal and dermal human skin DCs and contributes to the migratory capacity of DCs. Pharmacological inhibition of MRP4 activity or down-regulation through RNAi in DCs resulted in reduced migration of DCs from human skin explants and of in vitro generated Langerhans cells. The responsible MRP4 substrate remains to be identified as exogenous addition of MRP4's known substrates prostaglandin E2, leukotriene B4 and D4, or cyclic nucleotides (all previously implicated in DC migration) could not restore migration. This notwithstanding, our data show that MRP4 is an important protein, significantly contributing to human DC migration toward the draining lymph nodes, and therefore relevant for the initiation of an immune response and a possible target for immunotherapy.

Introduction

The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters were initially identified by their roles in clinical multidrug resistance (MDR) against a broad range of functionally and structurally unrelated anticancer agents.1 Over the past 10 years, it has become apparent that several of the ABC transporters transport not only cytostatic agents but also inflammatory mediators such as platelet activating factor,2 leukotrienes,3 or prostaglandins.4 Unraveling the specific roles of ABC transporters in the functioning of the immune system may therefore reveal new links for future immunotherapeutic approaches

Dendritic cells (DCs) are key initiators of the immune response, sampling their surroundings for foreign antigens.5 They are also seen as a promising tool for targeted immunotherapeutic strategies.6 We have shown that dendritic cell differentiation is impaired when the transporter activity of Multidrug Resistance Protein 1 (MRP1; ABCC1) is inhibited.7 Randolph and coworkers previously reported that both P-glycoprotein (P-gp; ABCB1) and MRP1 are required for optimal DC migration.8,9 The ABC transporter MRP4 (ABCC4)10–12 is an organic anion transporter and has been described to transport prostaglandins such as PGA2, PGE1, and PGE2.4 Because PGE2 is believed to be crucial for DC migration,13–15 we explored the role of this ABC transporter in DC migration. Moreover, a recent study showed that MRP4, like MRP1, can transport leukotrienes (eg, LTB4 and LTC4).16 Thus, when expressed on DCs, MRP4 could have contributed to the original observations made for the role of MRP1 in DC migration,9 because the used antagonist MK-571 can inhibit both transporters. In this manuscript we show that MRP4 is abundantly expressed in epidermal human skin DCs and at lower levels in dermal human skin DCs. To demonstrate functionality and to study the involvement of MRP4 in human DC migration, we made use of the human AML cell line MUTZ3,17 which can be cultured in vitro into CD1a+ DC-SIGN+ interstitial DCs (MUTZ3-DCs) and CD1ahi langerin+, Birbeck granule+ Langerhans cells (MUTZ3-LC),18,19 and a human skin-explant migration model. After confirming expression of MRP4 in MUTZ3-DCs and MUTZ3-LCs, we made use of the MRP4 antagonist sildenafil20 and viral shRNA constructs against MRP4 to show that MRP4 is needed for optimal DC migration toward the lymph node-homing chemokines CCL19 (MIP3β) and CCL21 (6Ckine). In the human skin explant experiments, we made use of an adenoviral construct encoding shRNA against MRP1 or MRP4. Also in human skin, interference with MRP4 inhibited DC migration. Together, these data provide strong evidence that in addition to P-gp and MRP1, MRP4 plays a significant role in human DC migration.

Methods

Chemicals

Unless otherwise indicated, all chemicals and drugs were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO) except for sildenafil citrate, which was kindly provided by Pfizer (Walton Oaks, United Kingdom).

Control cell lines

The human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cell line and its MRP4-transduced sub line (HEK-MRP4)21 were used as control cell lines where indicated. For MRP1, the small-cell lung carcinoma cell line GLC4 and its MRP1 expressing subline GLC4/ADR were used.22

Viruses

The retroviral constructs pSUPER.vector, pSUPER.shMRP1 (sequence: gatcccc GGAGTGGAACCCCTCTCTG ttcaagaga CAGAGAGGGGTTCCACTCC tttttggaaa), pSUPER.shMRP4 (sequence: gatcccc GATGGTGCATGTGCAGGAT ttcaagaga ATCCTGCACATGCACCATC tttttggaaa), pRetroSUPER(pRS).puro.vector, pRS.puro.shMRP1, and pRS.puro.shMRP4 were kind gifts of Prof P. Borst (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The pRS.GFP was a kind gift of Dr R. Agami (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). pRS.GFP.shMRP4 constructs were generated by enzyme digestion (EcoRI-XhoI) of the pSUPER.shMRP4 to remove the H1-promotor and shMRP4 insert. The insert was ligated into EcoRI-XhoI digested linear pRS.GFP. Retroviruses were propagated in Phoenix A cells by plasmid DNA transfection. The culture medium was refreshed after 24 hours and viral supernatants were harvested 48 hours after transfection.

Adenoviruses encoding the shRNA against MRP1 and MRP4 were generated by enzyme digestion of pSUPER.shMRP1 and –shMRP4, with XbaI and XhoI, to isolate the H1 promotor and shRNAi constructs. These were cloned into an XbaI + XhoI digested pAdTrack.CMV adenoviral shuttle vector, which contains an eGFP reporter gene. pAdTrack.CMV, pAdTrack.shMRP1 and –shMRP4 were transformed into BJ5183-AD1 cells, stably transfected with pAdEasy1 for homologous recombination (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Colonies were analyzed for the correct homologous recombination via PacI digestion. pAdEasy.CMV, pAdEasy.shMRP1, and pAdEasy.shMRP4 plasmid DNA was generated in electrocompetent bacteria and purified. Adenoviruses were propagated in 293 cells and isolated by CsCl-gradient purification.

DC and LC cultures

Interstitial DCs were either cultured from human peripheral blood monocytes of healthy donors (MoDC) as described before23 or from the human acute myeloid leukemia cell line MUTZ-3, also as described previously.18 In brief, MUTZ3 progenitors were cultured in MUTZ3 routine medium consisting of minimum essential medium-α (MEM-α; Lonza, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 IU/mL sodium-penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μmol/L β-mercaptoethanol (2ME), and 10% conditioned medium from the 5637 renal cell carcinoma cell line (MUTZ3 routine medium). Cells were plated in 12-well plates (Costar; Corning Life Science, Acton, MA) at a concentration of 0.2 million cells/mL and were passaged twice weekly. The DCs and LCs were cultured in MEM-α with 20% FCS, 100 IU/mL sodium-penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 50 μmol/L 2ME. MUTZ3-DCs were cultured from MUTZ3 by adding 1000 IU/mL recombinant human granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (rhGM-CSF, Sagramostim; Berlex Laboratories, Wayne, NJ), 10 ng/mL interleukin-4 (IL-4; R&D Diagnostics, Minneapolis, MN), and 2.5 ng/mL tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) for 6 days, adding fresh cytokines on day 3. MUTZ3-LCs were cultured with 1000 IU/mL rhGM-CSF, 10 ng/mL transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1; Biovision, Mountain View, CA), and 2.5 ng/mL TNFα as described previously.7 Where applicable, immature DCs/LCs were matured at day 6 or 10, respectively, by adding 50 ng/mL TNFα, 100 ng/mL interleukin-6 (IL-6; Strathmann Biotec), 25 ng/mL IL-1β (Strathmann Biotec), and 1 μg/mL prostaglandin E2 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 days.

Immunocytochemistry

Sections were made from frozen skin biopsies. Cytospin preparations were made of cell suspensions by centrifugation for 4 minutes at 650 rpm. Skin sections and cytospins were air-dried overnight and fixed in 100% acetone for 10 minutes. Immunocytochemical analysis was performed as described previously,7 using the anti-MRP4 rat monoclonal antibody M4I-10 (5 μg/mL)24 to detect MRP4. Cytospins and tissues were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted with Kaiser's glycerol gelatin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Isotype-matched rat IgG antibodies were used as negative controls. Fluorescent double-stainings of skin sections for MRP4 (M4I-10) and CD1a (CD1a-FITC; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) were performed as described previously.7 At room temperature, with air as medium, expression was analyzed using a Leica DMR fluorescent microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with 40×/0.75 HCX PL Fluotar and 10×/0.30 and 20×/0.50 HC PL Fluotar objectives (Leica). Images were captured using a Leica DC200 digital camera (Leica Microsystems, Rijswijk, The Netherlands) and Leica DC Viewer (Leica Microsystems, Heerbrugg, Germany) and RVC Research assistant 3 (RVC, Baarn, The Netherlands) software.

Flow cytometric phenotypic analyses

DCs were immunophenotyped using fluorescein isothiocyanate-, phosphatidylethanolamine-, or allophycocyanin-conjugated monoclonal antibody: anti-CD1a (1:25), anti-CD54 (1:25), anti-CD86 (1:25), anti-CD40 (1:10; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), anti-CD14 (1:25), anti–HLA-DR (1:25; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), anti-langerin (CD207), anti-CD83 (1:10; Immunotech, Marseilles, France), and anti-CD34 (1:10; Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands); 2.5 to 5 × 104 cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 0.02% NaN3 and incubated with specific or corresponding control Mabs for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) equipped with CellQuest analysis software.

Skin explant DCs

Skin explant cultures and skin DC migration assays, with subsequent analysis, were performed as described previously.25 For MRP4 blocking during migration sildenafil citrate diluted in water was injected intradermally at indicated doses (range, 6.7-60 μmol/L) in a total volume of 20 μL, after which 6-mm punch biopsies were taken. Sildenafil was also added to the culture medium in the same indicated concentrations. DCs were allowed to migrate from the biopsies for 2 days before harvesting, quantification by Trypan blue exclusion and flow cytometric analysis to phenotype the cells.

For adenoviral shRNA experiments, human skin was preconditioned by injecting 1000 IU/mL GM-CSF and 10 ng/mL IL-4 to mature the skin DCs and induce CD40 expression for CD40-targeted adenovirus (Ad) mediated transductions as described previously.25 Six-mm punch biopsies were made and incubated on grids for 24 hours. Biopsies were injected by 109 viral particles/biopsy as described previously.6 Ad were preincubated with 625 ng of the CD40-targeting sCAR-mCD40L fusion protein CFm40L26 at room temperature for 60 minutes and then injected into biopsies in a total volume of 10 μL. Biopsies were transferred to 48-well plates containing 1 mL Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM), 5% human pooled serum, and 100 IU/mL sodium-penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine per well. Cells were allowed to migrate for 2 days, after which migrated DCs were harvested, quantified by trypan blue exclusion, and phenotyped by flow cytometry.

Isolation of CD1a+ epidermal and dermal skin DCs

CD1a+ epidermal and dermal skin DCs were isolated by collecting 2 to 3-mm thick skin sheets from healthy donor skin with a dermatome (Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany). Skin was incubated in 50 ng/mL Dispase II (Roche, Penzbeg, Germany) for 20 to 60 minutes at 37°C to separate the dermis and epidermis. Epidermal sheets were then incubated in 0.05% trypsin at 37°C for 15 to 30 minutes and resuspended in IMDM + 10% FCS. Single cell suspensions were made by pushing 1% trypsin-treated epidermal sheets through a 100-μm sterile filter. Dermal skin was incubated in collagenase (200 mg of collagenase diluted in 26.6 mL of PBS and 6.6 mL of Dispase II) for 90 minutes at 37°C. Single-cell suspensions were made by filtration through 100-μm sterile filters. Viable cells were counted by Trypan blue exclusion and CD1a+ cells were purified by magnetic bead sorting (MACS) using Miltenyi anti–CD1a-magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). The isolated populations were checked for purity, based on CD1a expression in conjunction with Langerin. Cytospins were made of the CD1a+ epidermal and dermal cells and were stained for MRP4 as described above.

Lightcycler PCR

RNA was isolated using RNA-Bee (Bio-connect, Huissen, The Netherlands), following the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA concentration was determined on a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of RNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA samples were diluted 1:15, and 5 μL cDNA was used in a Lightcycler PCR reaction using Lightcycler FastStart DNA Masterplus HybProbe (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using fluorescence-labeled TaqMan probes for MRP4 and β-actin, which were designed using Lightcycler probe design software (Roche Molecular Diagnostics). (MRP4: forward 5′→3′ primer, TGGATTCTGTGGCTTTGAACAC; reverse 5′→3′ primer, AGCCAAAATGAGCGTGCAA; probe, CGTACGCCTATGCCACGGTGCTG; β-actin: forward 5′→3′ primer: TCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTACGA; reverse 5′→3′ primer, CAGCGGAACCGC-TCATTGCCAATGG; probe, ATGCCCTCCCCCATGCCATCCTGCGT). The relative mRNA ratios given are the concentration of MRP4 mRNA divided by the concentration of β-actin mRNA for the given samples, based on a titration curve of MRP4 mRNA levels of the MRP4-positive cell line HEK-MRP4.

MUTZ3 retroviral transduction

MUTZ3 cells were passaged 24 hours before transduction. MUTZ3 progenitor cells (5 × 105) were transferred to 40 μg/mL retronectin-coated (Takara, Kyoto, Japan) non–tissue culture-coated 24-well plates (BD Bioscences) in 1 mL of control vector, shMRP1, or shMRP4 retroviral supernatant. Plates were centrifuged for 90 minutes at 2000 rpm at 25°C. Transduced MUTZ3 cells were retransduced with fresh viral supernatant 24 hours later. Hereafter, cells were washed and plated in routine MUTZ3 culture medium. After 3 days, cells were analyzed for green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression, and the GFP+ cells were sorted using a FACS STAR flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Low-density DNA microarray

ABC transporter gene expression of the MUTZ3-control vector and MUTZ3-shMRP4 cell lines was analyzed with the use of an ABC transporter low-density DNA microarray (DualChip human ABC, kindly provided by J. P. Gillet and J. Remacle, University of Namur, Namur, Belgium) as described previously.27 In short, mRNA was isolated using RNA-Bee, following the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA concentration was determined on a Nanodrop spectrophotometer, and RNA integrity was verified by capillary electrophoresis on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Labeled cDNA were prepared from 10 to 20 μg of mRNA. As internal standard, 3 synthetic poly-A+ tailed RNA samples were added to the purified mRNA at 3 different concentrations (10, 1, and 0.1 ng per reaction), as described in more detail previously.28 Hybridization and statistical analysis were performed as described previously.28 All microarray data have been deposited at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE12089.

Transwell migration toward CCL19 and CCL21

For in vitro transwell migration assays, 105 mature MUTZ3-LCs cultured from MUTZ3-pRS.GFP.vector and MUTZ3-shMRP4 were seeded in the upper compartment of Costar 24-well transwells with a pore size of 6 μm. The lower compartment contained 600 μL of serum-free IMDM supplemented with 100 IU/mL sodium-penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 25 μg/mL CCL19 (Peprotech, Huissen, The Netherlands) or CCL21 (Invitrogen). Cells were allowed to migrate for 4 hours at 37°C. After migration, 500 μL of medium was harvested from the lower compartment, and migrated cells were phenotyped and quantified with flow-count fluorospheres (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) by flow cytometry. To study the effect of known MRP4 substrates on migration, cells were preincubated with 1 to 2 μg/mL PGE2, 1-200 nM LTB4, or 100 to 200 nM LTD4 (Cayman Chemicals, Montigny de Bretonneux, France), 50 μmol/L 8Br-cGMP (Sigma-Aldrich), or a combination of the 4 substrates for 60 minutes at room temperature before starting the migration toward CCL19. The substrates remained present during migration.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses of the data were performed using the paired or unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P less than .05.

Results

MRP4 is expressed on CD1a+ epidermal and dermal DCs

Human skin biopsies were used to study the expression of MRP4 on epidermal and dermal DCs. Sections from frozen skin were stained for MRP4 using the M4I-10 Mab.24 MRP4 was found to be present in the epidermal layer of the skin on cells with dendritic morphology (Figure 1A,B). MRP4 expression was studied in 6 different donors; in all donors, cells with clear DC morphology were found to express this transporter in the epidermis. Figure 1B shows close-up views of epidermal and dermal cells positive for MRP4 from 2 donors. MRP4 expression on dermal DCs was detected, though less frequently (3/6 donors) and with a lower staining intensity.

Figure 1.

MRP4 expression on human cutaneous DCs. Human skin was stained with isotype control antibody or the Mab M4I-10 to detect MRP4. (A) An overview of the skin section (original magnification, 100×) and (B) details of MRP4-positive cells within the epidermis (left) or dermis (right) are shown (original magnification, 400×). (C) Epidermis was stained for MRP4 (red, Cy3) and CD1a (green, fluorescein-labeled tyramine; original magnification, 400×). Both MRP4 and CD1a are expressed in the same cells (merge). MRP4 signals were weaker than CD1a signals and were therefore measured with a longer shutter time. (D) CD1a+ epidermal (left) and dermal (right) cells were isolated by magnetic bead sorting and analyzed for CD1a and Langerin expression by flow cytometry and cytospins were stained for MRP4 expression (original magnification, 400×).

To demonstrate that the MRP4-expressing cells indeed represented DCs, skin sections were costained for MRP4 and the DC marker CD1a. Epidermal cells expressing MRP4 (red) were also positive for the LC/DC marker CD1a (green), proving that these are in fact DCs expressing MRP4 (Figure 1C). CD1a+ epidermal DCs and CD1a+ dermal DCs were also isolated from epidermis and dermis through CD1a-based magnetic bead separation. Cell purity and characteristics of the epidermal DCs (Figure 1D) and the dermal DCs (Figure 1E) were determined by flow cytometry. All isolated cells from epidermis and dermis were CD1a+, whereas only the epidermal cells expressed the LC-specific marker langerin. Analysis of cytospin preparations of these cells showed that both CD1a+ epidermal and dermal DCs expressed MRP4 and that the staining was strongest on the epidermal LCs (Figure 1D,E).

Inhibition of MRP4 activity decreases skin DC migration

To study a putative contribution for MRP4 in skin DC migration, the previously described MRP4 inhibitor sildenafil was intradermally injected into skin explants in 3 concentrations (6.7, 20, and 60 μmol/L, 20 μmol/L being the reported IC50 for MRP4 inhibition20). DCs were allowed to migrate from the 6-mm biopsies for 2 days, after which the biopsies were removed and migrated cells were harvested, quantified, and phenotyped. Figure 2 shows a dose-dependent reduction of migrated numbers of skin-DCs from the biopsies. The migration was significantly reduced by 20 μmol/L sildenafil (P = .02) and 60 μmol/L sildenafil (P < .01) by about 50% and 60%, respectively (n = 3). Analysis of marker expression of the migrated DCs did not show substantial differences with respect to the percentage of CD1a+ cells within the migrated DCs population or the maturation status of the migrated cells (data not shown).

Figure 2.

MRP4 inhibition reduces human skin DC migration. Human skin explants were intradermally injected with 20 μL of plain medium, or 20 μL containing 6.7, 20, or 60 μmol/L sildenafil. Sildenafil was also added to the culture medium of the respective samples at the same concentrations. Migrated skin DCs were harvested after 24 hours and quantified. Compared with the medium condition, significantly less cells migrated when skin was injected with 20 μmol/L (50% reduction; P < .03) or 60 μmol/L (60% reduction; P < .01) sildenafil (n = 3; 20 biopsies per condition per experiment).

MRP4 knock-down inhibits MUTZ3-LC migration toward CCL19 and CCL21

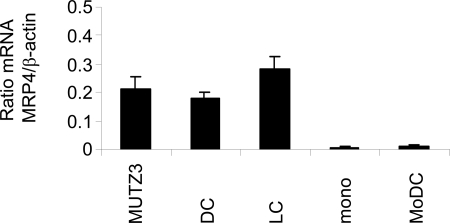

MRP4 protein expression was below the limit of immunohistochemical detection on monocytes or immature and mature monocyte-derived DCs (MoDC). However, MRP4 protein expression was detected on MUTZ3 progenitor cells and on in vitro cultured immature and mature MUTZ3-DCs and MUTZ3-LCs by immunocytochemistry (data not shown). Because the MUTZ3 cell line functions as a previously described relevant model for in vitro generation of human interstitial DCs and LCs that phenotypically and functionally closely resemble their physiological cutaneous counterparts,19,29,30 this cell line was used for further in vitro MRP4 studies. Given the notion that a previous study by Angénieux et al31 reported MRP4 mRNA expression in MoDC, mRNA levels were also checked by semiquantitative RT-PCR for monocytes and MUTZ3 progenitors as well as for differentiated MoDC and MUTZ3-DCs and MUTZ3-LCs. Whereas only low levels of MRP4 mRNA were detected in monocytes and MoDC, MRP4/β-actin mRNA ratios were much higher in MUTZ3 progenitors, MUTZ3-DCs, or MUTZ3-LCs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

MRP4 mRNA levels in in vitro cultured DCs. MRP4 mRNA levels were determined in MUTZ3 progenitors, in differentiated, immature MUTZ3-DCs (DC) and MUTZ3-LCs (LC), in monocytes (mono) and in immature MoDC (MoDC) by Lightcycler RT-PCR. Depicted are the mRNA ratios compared with mRNA values for β-actin (n = 3; mean ± SD).

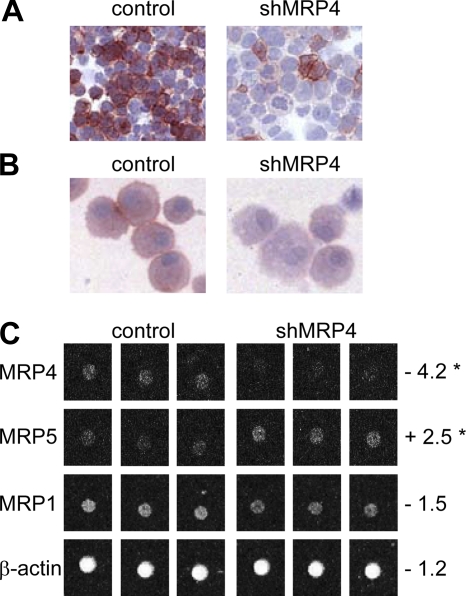

Sildenafil citrate is known to increase intracellular cGMP levels by inhibition of the enzyme phosphodiesterase 5,32 and cyclic nucleotide levels have been described to influence DC migration and maturation.33–35 Therefore, a retroviral vector encoding shRNA against MRP4 (pRS.GFP.shMRP4) was generated to distinguish between the effects of sildenafil on cGMP levels and a specific role of MRP4 in DC migration. MUTZ3 progenitor cells were transduced with pRS.GFP.shMRP4. The shRNA construct was first tested in MRP4-positive human embryonic kidney cells (HEK-MRP4). As depicted in Figure 4A, transfection of HEK-MRP4 cells with the pRS.shMRP4.puro construct resulted in a clear reduction in MRP4 expression compared with the vector control (pRS.puro). Figure 4B shows reduced MRP4 expression in LCs cultured from MUTZ3.shMRP4 cells compared with MUTZ3-pRS.GFP (control); mRNA expression for MRP4 and, as a control, for MRP1 and MRP5, was analyzed with the use of a low-density ABC transporter array.27 MRP4 mRNA was consistently and significantly reduced to background levels (Figure 4C). It is noteworthy that there was a significant induction of MRP5 mRNA expression, whereas mRNA levels for MRP1 or β-actin were not significantly altered upon MRP4 RNA interference (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

shMRP4 down-regulates MRP4 protein and mRNA expression. MRP4 protein expression analyzed by immunocytochemistry in HEK-MRP4 cells transduced with pRetroSUPER.puro.vector (A, left; control) or pRetroSUPER.shMRP4.puro (A, right) or LC cultures from MUTZ3 stably transfected with pRetroSUPER.GFP.vector (B, left; control), or pRetroSUPER.GFP.shMRP4 (B, right). Original magnification, 100×. (C) Triplicate MRP4 mRNA levels measured by low-density array in MUTZ3-vector control (left) or MUTZ3-shMRP4 cells (right). Numbers indicate the fold increase (+) or decrease (−) with respect to MUTZ3-vector control levels (*P < .05).

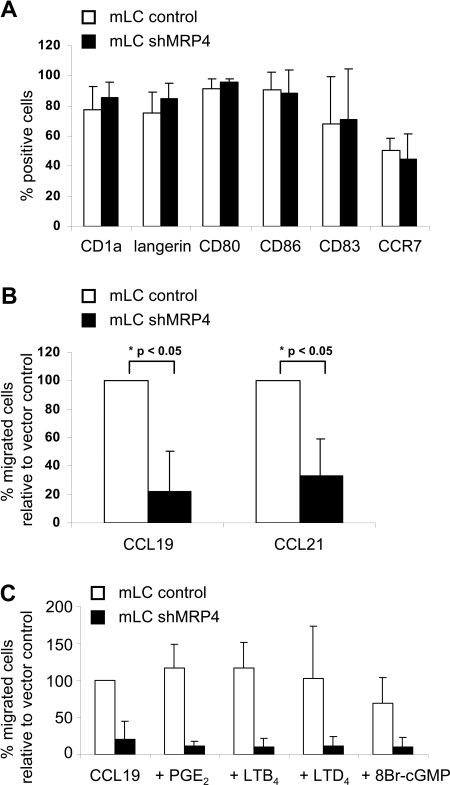

Flow cytometric analysis of LCs cultured from MUTZ3-control or MUTZ3-shMRP4 showed normal LC phenotype after differentiation and maturation (Figure 5A). These LCs were used in trans-well migration assays toward the chemokines CCL19 and CCL21. It is noteworthy that the percentage of CCR7-positive cells (Figure 5A) and the expression levels of CCR7 were similar on MUTZ3-control and -shMRP4 mLC (mean fluorescence, 22.8 ± 6.2 and 27.2 ± 4.4 for MUTZ3-control and -shMRP4 mLC, respectively). Nonetheless, down-regulation of MRP4 expression on LCs significantly reduced their migration toward CCL19 (P = .041) and CCL21 (P = .047) compared with control MUTZ3-LCs (Figure 5B; n = 3). This result suggests that lack of proficient MRP4 expression withholds cellular extrusion of a MRP4 substrate that promotes DC migration. However, exogenous addition before and during migration of a relevant concentration of known MRP4 substrates PGE2 (1-2 μg/mL),13–15 LTB4 (1-200 nmol/L),36 the LTC4-derivative LTD4 (100-200 nmol/L)9 or 8-bromo-cGMP (50 μmol/L35; Figure 5C), previously reported to promote DC migration, could not restore migration of MUTZ3-shMRP4 LCs. Also, the addition of a combination of all of the above mentioned substrates did not improve DC migration (data not shown).

Figure 5.

MRP4 down-regulation hampers mLC migration toward CCL19 and CCL21. (A) MUTZ3-vector control and MUTZ3-shMRP4 cells were differentiated into LCs and matured by addition of a cytokine cocktail (see “Methods”). Phenotypic analysis (n = 4) is depicted and shows no abnormal differentiation due to the absence of MRP4. Mature LCs were allowed to migrate in a transwell assay toward the chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 either immediately (B) or after (C) preincubation with typical MRP4 substrates (PGE2, 1 μg/mL; LTB4 and LTD4, 200 nmol/L; 8-Br-cGMP, 50 μmol/L). The percentages migrated cells are given relative to the vector control migrated cells (n = 3 for panels B and C; mean ± SD).

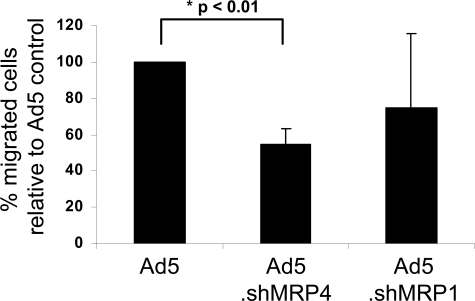

Targeted Ad5.eGFP.shMRP4 reduces human skin DC migration

To specifically target and modulate human skin DC migration by RNA interference, adenoviral constructs containing the shMRP4 sequence (Ad5.eGFP.shMRP4) or a shMRP1 sequence (Ad5.eGFP.shMRP1) were cloned. The Ad5.eGFP.shMRP1 was constructed from the pSUPER.shMRP1 plasmid and the efficiency of the shMRP1 was analyzed in the MRP1-overexpressing cell line GLC4-ADR. Transduction of GLC4-ADR cells with the pSUPER.shMRP1 efficiently reduced MRP1 protein expression (data not shown). Because MRP1 function was linked to murine and human DC migration,9 reduced migration was expected after DCs infection with the shMRP1 virus. Although commonly used wtAd5 vectors poorly infect human skin DCs, because their lack of the Ad5-binding receptor CAR,6 skin DCs can be efficiently infected and targeted in situ by a CD40-CD40L interaction.25 Here, we used a fusion protein consisting of a soluble CAR-domain linked to mouse CD40L (CFm40L),26 to target the adenoviral vectors to human skin DCs. This mCD40L was previously shown to bind human CD40 and enhance infection of human DCs.26 Adenoviruses, preincubated with CFm40L, were intradermally injected into human skin biopsies presensitized with GM-CSF + IL-4 to induce CD40 expression on cutaneous DCs and to optimize DC migration.25 The differences in the amount of migrated cells after Ad5.eGFP, Ad5.eGFP.shMRP1, and Ad5.eGFP.shMRP4 targeted Ad-injection are depicted in Figure 6. Specifically, cell migration from the biopsies injected with CD40-targeted Ad5.eGFP.shMRP4 was reduced by approximately 50% (P = .002) compared with Ad5.eGFP injected biopsies. A moderate (20%) reduction in DC migration was observed after Ad5.eGFP.shMRP1 injection, but this difference over Ad5.eGFP did not reach statistical significance. These data suggest that MRP4 might play an even more dominant role in human skin DC migration than MRP1.

Figure 6.

DC-targeted down-regulation of MRP4 reduced human skin DC migration. GM-CSF– and IL-4–activated human skin DCs were in situ (intradermally) targeted with adenoviruses encoding shMRP4 or shMRP1, using a sCAR-CD40L fusion protein (CFm40L) and a human skin explant culture model. After 48 hours, migrated DCs were harvested and quantified (n = 4 donors, 12-20 biopsies per condition per experiment; mean ± SD).

Discussion

This study provides several lines of evidence that the ABC transporter MRP4 contributes to human skin DC migration. Inhibition of MRP4 activity via intradermal injection of the MRP4 antagonist sildenafil reduced the amount of migrated skin DCs by 60% to 70% at the highest dose (60 μmol/L). Sildenafil was reported to block both MRP4 and MRP5 transporter activity.20 Because MRP5 expression was not observed in human skin sections (data not shown), effects of sildenafil on DC migration could not be attributed to blockade of MRP5 activity. The reduction in DC migration observed by the injection of sildenafil could conceivably be caused by a combined contribution of sildenafil-induced inhibition of MRP4 activity and elevation of intracellular cGMP levels. To pinpoint the effect to MRP4, we have therefore used RNAi. When infected with CD40-targeted Ad5.eGFP.shMRP4, skin DC migration was inhibited by approximately 40% to 50%. A measurable reduction in migrated cell numbers, but no significant inhibition was observed when a shMRP1-encoding Ad was used, suggesting that MRP4 might contribute more to human skin DC migration than MRP1. In the study by Robbiani et al,9 in which the authors showed that MRP1 is important for murine and human DC migration, human MRP1 activity in the skin was blocked with 10-25 μmol/L of the antagonist MK-571. This antagonist, however, can also block MRP4 activity at these concentrations,20 so possibly the inhibition on DC migration observed by Robbiani et al9 could be due to both MRP4 and MRP1 inhibition. A contribution of MRP1 in murine DC migration was clearly established based on observations that (1) DC migration was markedly attenuated in mrp1−/− animals, and (2) migration of murine mrp1-deficient bone marrow–derived DCs could effectively be restored by adding the MRP1 substrate LTC4 or its derivative LTD4. In this context, it is of interest to note that LTC4 was recently reported to be transported by human MRP4 as well.16 It could well be that the expression and function of the ABC transporters is different in different species (eg, mouse and human). It would be interesting to investigate to what extent DC migration, and thereby the general immune response, is hampered in mice lacking mrp4 expression. However, murine and human MRP4 have been reported to display different substrate specificities37; thus, MRP4 might conceivably play a different (and possibly less dominant) role in murine DC migration than in human DC migration.

Besides LTC4, the other known physiological MRP4 substrates, PGE2, LTB4, and cAMP/cGMP, could possibly influence DC migration. It has been established that endogenously processed PGE2 is important for the migratory capacity of DCs13; in addition, cyclic nucleotides can affect DC migration.33 Moreover, a recent study by Del Prete et al36 showed a role for LTB4 and LTB4 receptors in DC migration. Thus, conceptually speaking, DCs could use MRP4 for the secretion of endogenously produced cAMP, cGMP, PGE2, LTB4, or LTC4 and thereby promote their own migration. However, preincubation of MUTZ3-shMRP4 mLC with any or a combination of the above mentioned substrates could not abrogate the migration defect in these cells. Hence, the relevant MRP4 substrate that triggers DC migration remains to be identified. Because Del Prete et al reported that only low concentrations of LTB4 promoted DC migration, preincubation of MUTZ3.shMRP4 mLC with 1 nmol/L LTB4 before migration was also tested, but no effect on the migratory capacity of the cells was observed (data not shown).

The present data add an important physiological function to one of the ABC transporters, MRP4. ABC transporters were initially identified for their role in clinical multidrug resistance and seemed a promising target to increase intracellular drug levels by inhibiting their activity. However, emerging data show that these transporters are required for optimal functioning (and protection) of several organs38–41 and the immune system7–9,42 and fulfill essential tasks for the functioning of immune effector cells. Our observation that MRP4 is necessary for the migration of human skin DCs warrants caution when planning to use specific MRP4, or pan ABC transporter, antagonists to reduce MDR in patients who are resistant to (chemo)therapy. If such a treatment would lead to hampered DC migration and consequently a deprived immune response, this could give rise to more serious problems with respect to tumor surveillance by the immune system and protection against viral and bacterial infections during chemotherapy treatment. On the other hand, one could envision a combined chemoimmunotherapy strategy to augment MRP4 expression and functionality on human DCs (eg, by low-dose administration of cytostatic drugs or DC-targeted gene therapy) in combination with DC-activating adjuvants and tumor associated antigens, to enhance the DC migratory capacity in immune-suppressed patients, as a means to break immune suppression and induce an effective antitumor response.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pfizer United Kingdom for supplying us with the MRP4 antagonist sildenafil citrate.

This work was supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF) to R.J.S., G.L.S. and T.D.G. (KWF2003-2830), a grant from the National Institutes of Health to D.T.C. (P01CA104177), and travel grants from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF), the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), and the Dutch Society for Immunology (NvvI) to R.V.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: R.V. performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript. A.W.R. performed research and analyzed data. J.J.L and R.O. performed research. J.P.G performed low-density MDR array. G.J. contributed to the manuscript draft. J.N.G. and D.T.C. supervised adenoviral work and interpreted data. A.P. made and contributed CFm40L. G.L.S., R.J.S., and T.D.G. designed the research, interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tanja D. de Gruijl, PhD, Division of Immunotherapy, Department of Medical Oncology, VU University Medical Center, de Boelelaan 1117-CCA 2.22, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: td.degruijl@vumc.nl.

References

- 1.Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J. A family of drug transporters: the multidrug resistance-associated proteins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1295–1302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raggers RJ, Vogels I, van Meer G. Multidrug-resistance P-glycoprotein (MDR1) secretes platelet-activating factor. Biochem J. 2001;357:859–865. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leier I, Jedlitschky G, Buchholz U, et al. The MRP gene encodes an ATP-dependent export pump for leukotriene C4 and structurally related conjugates. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27807–27810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid G, Wielinga P, Zelcer N, et al. The human multidrug resistance protein MRP4 functions as a prostaglandin efflux transporter and is inhibited by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9244–9249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1033060100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuurhuis DH, Fu N, Ossendorp F, Melief CJ. Ins and outs of dendritic cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;140:53–72. doi: 10.1159/000092002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Gruijl TD, Ophorst OJ, Goudsmit J, et al. Intradermal delivery of adenoviral type-35 vectors leads to high efficiency transduction of mature, CD8+ T cell-stimulating skin-emigrated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:2208–2215. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Ven R, de Jong MC, Reurs AW, et al. Dendritic cells require multidrug resistance protein 1 (ABCC1) transporter activity for differentiation. J Immunol. 2006;176:5191–5198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randolph GJ, Beaulieu S, Pope M, et al. A physiologic function for p-glycoprotein (MDR-1) during the migration of dendritic cells from skin via afferent lymphatic vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6924–6929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robbiani DF, Finch RA, Jager D, et al. The leukotriene C(4) transporter MRP1 regulates CCL19 (MIP-3beta, ELC)-dependent mobilization of dendritic cells to lymph nodes. Cell. 2000;103:757–768. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allikmets R, Gerrard B, Hutchinson A, Dean M. Characterization of the human ABC superfamily: isolation and mapping of 21 new genes using the expressed sequence tags database. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1649–1655. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kool M, de Haas M, Scheffer GL, et al. Analysis of expression of cMOAT (MRP2), MRP3, MRP4, and MRP5, homologues of the multidrug resistance-associated protein gene (MRP1), in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3537–3547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borst P, de Wolf C, van de Wetering K. Multidrug resistance-associated proteins 3, 4, and 5. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:661–673. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luft T, Jefford M, Luetjens P, et al. Functionally distinct dendritic cell (DC) populations induced by physiologic stimuli: prostaglandin E(2) regulates the migratory capacity of specific DC subsets. Blood. 2002;100:1362–1372. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scandella E, Men Y, Legler DF, et al. CCL19/CCL21-triggered signal transduction and migration of dendritic cells requires prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2004;103:1595–1601. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legler DF, Krause P, Scandella E, Singer E, Groettrup M. Prostaglandin E2 is generally required for human dendritic cell migration and exerts its effect via EP2 and EP4 receptors. J Immunol. 2006;176:966–973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rius M, Hummel-Eisenbeiss J, Keppler D. ATP-dependent transport of leukotrienes B4 and C4 by the multidrug resistance protein ABCC4 (MRP4). J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:86–94. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu ZB, Ma W, Zaborski M, et al. Establishment and characterization of two novel cytokine-responsive acute myeloid and monocytic leukemia cell lines, MUTZ-2 and MUTZ-3. Leukemia. 1996;10:1025–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masterson AJ, Sombroek CC, de Gruijl TD, et al. MUTZ-3, a human cell line model for the cytokine-induced differentiation of dendritic cells from CD34+ precursors. Blood. 2002;100:701–703. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santegoets SJ, Masterson AJ, van der Sluis PC, et al. A CD34+ human cell line model of myeloid dendritic cell differentiation: evidence for a CD14+CD11b+ Langerhans cell precursor. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1337–1344. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0206111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid G, Wielinga P, Zelcer N, et al. Characterization of the transport of nucleoside analog drugs by the human multidrug resistance proteins MRP4 and MRP5. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1094–1103. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wielinga PR, Reid G, Challa EE, et al. Thiopurine metabolism and identification of the thiopurine metabolites transported by MRP4 and MRP5 overexpressed in human embryonic kidney cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:1321–1331. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zijlstra JG, de Vries EG, Mulder NH. Multifactorial drug resistance in an adriamycin-resistant human small cell lung carcinoma cell line. Cancer Res. 1987;47:1780–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroeijers AB, Reurs AW, Scheffer GL, et al. Up-regulation of drug resistance-related vaults during dendritic cell development. J Immunol. 2002;168:1572–1578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leggas M, Adachi M, Scheffer GL, et al. Mrp4 confers resistance to topotecan and protects the brain from chemotherapy. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7612–7621. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7612-7621.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Gruijl TD, Luykx-de Bakker SA, Tillman BW, et al. Prolonged maturation and enhanced transduction of dendritic cells migrated from human skin explants after in situ delivery of CD40-targeted adenoviral vectors. J Immunol. 2002;169:5322–5331. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereboev AV, Nagle JM, Shakhmatov MA, et al. Enhanced gene transfer to mouse dendritic cells using adenoviral vectors coated with a novel adapter molecule. Mol Ther. 2004;9:712–720. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillet JP, Efferth T, Steinbach D, et al. Microarray-based detection of multidrug resistance in human tumor cells by expression profiling of ATP-binding cassette transporter genes. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8987–8993. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Longueville F, Surry D, Meneses-Lorente G, et al. Gene expression profiling of drug metabolism and toxicology markers using a low-density DNA microarray. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santegoets SJ, Schreurs MW, Masterson AJ, et al. In vitro priming of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes using allogeneic dendritic cells derived from the human MUTZ-3 cell line. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1480–1490. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0142-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santegoets SJ, Bontkes HJ, Stam AG, et al. Inducing antitumor T cell immunity: comparative functional analysis of interstitial versus Langerhans dendritic cells in a human cell line model. J Immunol. 2008;180:4540–4549. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angénieux C, Fricker D, Strub JM, et al. Gene induction during differentiation of human monocytes into dendritic cells: an integrated study at the RNA and protein levels. Funct Integr Genomics. 2001;1:323–329. doi: 10.1007/s101420100037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeremy JY, Angelini GD, Khan M, et al. Platelets, oxidant stress and erectile dysfunction: an hypothesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:50–54. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luft T, Rodionova E, Maraskovsky E, et al. Adaptive functional differentiation of dendritic cells: integrating the network of extra- and intracellular signals. Blood. 2006;107:4763–4769. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kambayashi T, Wallin RP, Ljunggren HG. cAMP-elevating agents suppress dendritic cell function. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:903–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giordano D, Magaletti DM, Clark EA. Nitric oxide and cGMP protein kinase (cGK) regulate dendritic-cell migration toward the lymph-node-directing chemokine CCL19. Blood. 2006;107:1537–1545. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Del Prete A, Shao WH, Mitola S, et al. Regulation of dendritic cell migration and adaptive immune response by leukotriene B4 receptors: a role for LTB4 in up-regulation of CCR7 expression and function. Blood. 2007;109:626–631. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Wolf CJ, Yamaguchi H, van der Heijden I, et al. cGMP transport by vesicles from human and mouse erythrocytes. FEBS J. 2007;274:439–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rius M, Thon WF, Keppler D, Nies AT. Prostanoid transport by multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4/ABCC4) localized in tissues of the human urogenital tract. J Urol. 2005;174:2409–2414. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000180411.03808.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nies AT, Jedlitschky G, Konig J, et al. Expression and immunolocalization of the multidrug resistance proteins, MRP1-MRP6 (ABCC1-ABCC6), in human brain. Neuroscience. 2004;129:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denk GU, Soroka CJ, Takeyama Y, et al. Multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 is up-regulated in liver but down-regulated in kidney in obstructive cholestasis in the rat. J Hepatol. 2004;40:585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belinsky MG, Guo P, Lee K, et al. Multidrug resistance protein 4 protects bone marrow, thymus, spleen, and intestine from nucleotide analogue-induced damage. Cancer Res. 2007;67:262–268. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sundkvist E, Jaeger R, Sager G. Pharmacological characterization of the ATP-dependent low Km guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) transporter in human erythrocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:945–949. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00940-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]