Abstract

Chromosome segregation requires stable bipolar attachments of spindle microtubules to kinetochores. The dynein/dynactin motor complex localizes transiently to kinetochores and is implicated in chromosome segregation, but its role remains poorly understood. Here, we use the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo to investigate the function of kinetochore dynein by analyzing the Rod/Zwilch/Zw10 (RZZ) complex and the associated coiled-coil protein SPDL-1. Both components are essential for Mad2 targeting to kinetochores and spindle checkpoint activation. RZZ complex inhibition, which abolishes both SPDL-1 and dynein/dynactin targeting to kinetochores, slows but does not prevent the formation of load-bearing kinetochore–microtubule attachments and reduces the fidelity of chromosome segregation. Surprisingly, inhibition of SPDL-1, which abolishes dynein/dynactin targeting to kinetochores without perturbing RZZ complex localization, prevents the formation of load-bearing attachments during most of prometaphase and results in extensive chromosome missegregation. Coinhibition of SPDL-1 along with the RZZ complex reduces the phenotypic severity to that observed following RZZ complex inhibition alone. We propose that the RZZ complex can inhibit the formation of load-bearing attachments and that this activity of the RZZ complex is normally controlled by dynein/dynactin localized via SPDL-1. This mechanism could coordinate the hand-off from initial weak dynein-mediated lateral attachments, which help orient kinetochores and enhance their ability to capture microtubules, to strong end-coupled attachments that drive chromosome segregation.

Keywords: Centromere, aneuploidy, mitosis, kinetochore, microtubule, spindle, chromosome

In higher eukaryotes, kinetochores are built on the centromere region of chromosomes to connect to the microtubules of the nascent mitotic spindle after nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD). To avoid chromosome loss, kinetochores must be efficient at capturing microtubules emanating from the two spindle poles and at converting initial transient contacts into stable end-coupled attachments capable of resisting the forces that drive chromosome alignment (Nicklas 1988). A safeguard is provided by the mitotic spindle checkpoint, which delays cell cycle progression by producing a diffusible inhibitor at kinetochores that have not yet captured microtubules (Musacchio and Salmon 2007). Stable end-on attachments shut off production of the inhibitory signal, allowing the cell to exit mitosis.

The core microtubule attachment site at the kinetochores is formed by a set of conserved interacting proteins, collectively named the KMN network after its constituent components KNL-1, the Mis12 complex, and the Ndc80 complex (Cheeseman et al. 2004). The network contains two microtubule-binding sites, one in KNL-1 and the other in the Ndc80 complex (Cheeseman et al. 2006; Wei et al. 2007). In eukaryotes ranging from yeast to human cells, compromising Ndc80 complex function in vivo leads to severe chromosome alignment defects correlated with an inability of kinetochores to form stable bipolar attachments (Kline-Smith et al. 2005).

Additional kinetochore–microtubule interactions are mediated by the microtubule minus-end-directed motor cytoplasmic dynein and its cofactor dynactin. Because dynein/dynactin has multiple functions in the cell, insight into its kinetochore roles has primarily come from studies on the conserved Rod/Zwilch/Zw10 (RZZ) complex (Smith et al. 1985; Karess and Glover 1989; Williams and Goldberg 1994; Scaerou et al. 1999, 2001; Williams et al. 2003), which is essential for kinetochore recruitment of dynein/dynactin (Starr et al. 1998). Inhibitions of RZZ subunits (Savoian et al. 2000; Li et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2007) and direct disruption of dynein/dynactin (Vorozhko et al. 2008) have shown that the minus-end-directed motility of kinetochore dynein contributes to transient poleward movement of chromosomes in early prometaphase (Rieder and Alexander 1990). Inhibition of dynein/dynactin also affects the microtubule-based poleward transport of checkpoint proteins and RZZ subunits, which is thought to constitute an important mechanism for silencing the spindle checkpoint (Howell et al. 2001; Wojcik et al. 2001).

Despite significant work over the past decade, the relevance of kinetochore dynein/dynactin for the process of chromosome alignment remains unclear. When dynein/dynactin is inhibited following bipolar spindle assembly, metaphase plate formation occurs normally (Howell et al. 2001; Vorozhko et al. 2008). Similarly, Drosophila melanogaster null mutations in the rod and zw10 genes were reported as having no obvious phenotype prior to anaphase in mitotic cells (Williams et al. 1992; Williams and Goldberg 1994). In contrast, recent work in mammalian cells showed significant delays in chromosome alignment after depletion of Zw10 (Li et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2007). The dissection of RZZ complex function in chromosome alignment is complicated by its role in spindle checkpoint signaling. Analysis in D. melanogaster embryos, human cells, and Xenopus extracts demonstrated that the RZZ complex is essential for spindle checkpoint function (Basto et al. 2000; Chan et al. 2000; Kops et al. 2005) and for the localization to unattached kinetochores of two essential spindle checkpoint components, Mad1 and Mad2 (Buffin et al. 2005; Kops et al. 2005).

The detection of a two-hybrid interaction between Zw10 and the dynactin subunit dynamitin suggested that the RZZ complex is directly involved in recruiting dynein/dynactin (Starr et al. 1998). A recent study in D. melanogaster identified Spindly, a component acting downstream from the RZZ complex, which is required for targeting dynein, but not dynactin, to kinetochores (Griffis et al. 2007). NudE and NudEL, two proteins that associate with dynein, have also been implicated in dynein targeting to kinetochores (Stehman et al. 2007; Vergnolle and Taylor 2007).

We developed the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo as a system to identify proteins that play important roles in chromosome segregation and characterize their mechanism of action (Oegema et al. 2001; Desai et al. 2003; Cheeseman et al. 2004). Here, we use this system to study the function of the Rod/Zwilch/Zw10 (RZZ) complex and Spindly (SPDL-1), components of the outer kinetochore that are essential for spindle checkpoint function and constitute a module that targets the dynein/dynactin motor to the kinetochore during chromosome alignment. A comparative analysis of SPDL-1 and RZZ complex function revealed that, despite their equivalent requirement for dynein/dynactin recruitment, SPDL-1 inhibition results in a significantly more severe defect in chromosome segregation, which, until just prior to anaphase onset, closely mimics the lack of stable end-coupled attachments. This defect can be quantitatively reduced to match that of inhibiting the RZZ complex alone by coinhibiting SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex. Thus, by uncoupling kinetochore localization of the RZZ complex from that of dynein/dynactin, we uncovered a regulatory relationship between the RZZ complex and the formation of stable end-coupled attachments. We discuss the implications of these findings for dynein/dynactin function at the kinetochore.

Results

The C. elegans Spindly homolog C06A8.5/SPDL-1 is required for chromosome segregation

All C. elegans proteins essential for chromosome segregation are required for embryonic viability. Embryos individually depleted of each of the ∼2000 gene products required for embryonic viability have been filmed using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy to identify genes whose inhibition results in the presence of extra nuclei (karyomeres) due to chromosome missegregation (Sonnichsen et al. 2005). However, since missegregation does not always lead to the formation of karyomeres and DIC does not directly visualize chromosomes, it is likely that chromosome segregation genes have been missed by this approach. To test this idea, we used RNAi to target 50 genes of unknown function required for embryonic viability but annotated as having no defects by DIC analysis in a strain coexpressing GFP:histone H2B and GFP:γ-tubulin to visualize chromosomes and spindle poles, respectively (Oegema et al. 2001). This screen identified one previously uncharacterized gene, C06A8.5, whose depletion resulted in severe chromosome missegregation. C06A8.5 encodes a 479-amino-acid protein that contains five predicted coiled-coil domains in its N-terminal 360 residues. Sequence searches identified potential homologs throughout the animal kingdom, including the previously characterized D. melanogaster Spindly (Griffis et al. 2007). Although C06A8.5 shows low sequence identity with the other proteins, it shares a highly conserved motif located near a break in the coiled-coils (Fig. 1C; Supplemental Fig. 1). As our functional analysis supports the idea that C06A8.5 is a Spindly homolog, we named the C. elegans protein SPDL-1.

Figure 1.

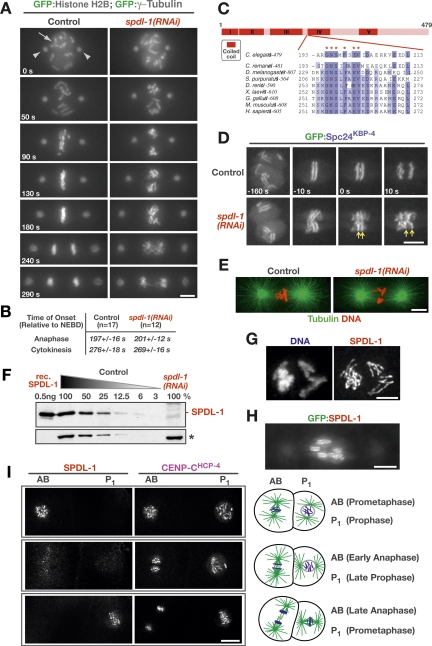

SPDL-1 is a transient kinetochore component essential for chromosome segregation. (A) Selected frames from a live-imaging sequence of the first division in unperturbed and spdl-1(RNAi) embryos expressing GFP:histone H2B and GFP:γ-tubulin to simultaneously visualize chromosomes (arrow) and spindle poles (arrowheads), respectively (see also Supplemental Movie 1). Images are time-aligned relative to NEBD (0 sec). Bar, 5 μm. (B) Timing of anaphase onset and cytokinesis onset in unperturbed and spdl-1(RNAi) embryos. Anaphase onset was defined as the first visible sister chromatid separation (GFP:histone H2B) and cytokinesis onset by the first visible ingression of the cleavage furrow in DIC images acquired in parallel. Values represent the S.E.M with a 95% confidence interval. (C) Primary sequence features of SPDL-1 and related proteins. The highly conserved motif that defines this conserved coiled-coil protein family is depicted (see also Supplemental Fig. 1). (D) Chromosome condensation, sister centromere resolution, and the separation of sister chromatids at anaphase onset are normal in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos. Selected frames of a live-imaging sequence are shown (see also Supplemental Movie 2). Kinetochores are marked by GFP:Spc24KBP-4, a subunit of the NDC-80 complex. Arrows highlight separating sister kinetochores at anaphase onset (0 sec) in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos. Bar, 5 μm. (E) Mitotic spindle morphology in control and spdl-1(RNAi) embryos fixed and stained with a fluorescently labeled antibody against α-tubulin (see also Supplemental Movie 3). Bar, 5 μm. (F) Immunoblotting with an affinity-purified polyclonal antibody raised against SPDL-1 detects purified recombinant (rec.) SPDL-1 and a protein of equal size in wild-type (N2) worms, which is depleted >95% by RNAi. The relative amount of worm extract loaded is indicated above each lane. A cross-reacting protein band (*) serves as the loading control. (G) Immunofluorescence image of a one-cell embryo at prometaphase immunostained for SPDL-1. Bar, 2 μm. (H) Snapshot of a one-cell embryo in prometaphase expressing GFP:SPDL-1. Bar, 5 μm. (I) SPDL-1 localizes transiently to kinetochores from prometaphase to anaphase onset. Two-cell embryos at different stages are shown costained for CENP-CHCP-4, which is present at kinetochores throughout mitosis, and SPDL-1. The natural difference in cell cycle timing of the AB and P1 cells (with AB entering and exiting mitosis prior to P1, as diagrammed on the right) defines the transient period of SPDL-1 kinetochore localization (see also Supplemental Movie 4). Bar, 5 μm.

Embryos depleted of SPDL-1 exhibited defective chromosome alignment, premature spindle pole separation, and significant chromatin bridges in anaphase (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Movie 1). The onset of both sister chromatid separation and cytokinesis occurred with normal timing in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos, indicating that cell cycle progression was unaffected (Fig. 1B).

The chromosome missegregation observed in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos could be the result of compromised mitotic chromosome structure, an aberrant mitotic spindle, or a defect in kinetochore function. To distinguish between these possibilities, we imaged a worm strain expressing GFP:Spc24KBP-4, a subunit of the outer kinetochore NDC-80 complex (Cheeseman et al. 2004). In spdl-1(RNAi) embryos, GFP:Spc24KBP-4 localized normally to paired diffuse kinetochores that maintained a rigid parallel conformation during prometaphase chromosome movements, demonstrating that centromere resolution and chromosome condensation were unaffected (Fig. 1D; Supplemental Movie 2). Sister kinetochores remained paired until the onset of anaphase, when individual chromatids separated from each other (Fig. 1D, arrows), indicating proper regulation of sister chromatid cohesion. All microtubule-dependent events in the early embryo (pronuclear migration, rotation of the centrosome–pronuclear complex, spindle assembly, and asymmetric spindle positioning) were normal in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos. In particular, fixed and live analysis in a worm strain expressing GFP:β-tubulin showed that mitotic spindle formation in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos was not perturbed (Fig. 1E; Supplemental Movie 3). We conclude that the severe chromosome segregation defect in embryos depleted of SPDL-1 does not result from problems with either the microtubule cytoskeleton, mitotic spindle formation, or chromosome structure.

Immunoblotting using affinity-purified antibodies confirmed that our RNAi conditions resulted in penetrant depletion of SPDL-1 (Fig. 1F). Immunostaining revealed that SPDL-1 is recruited to kinetochores at NEBD and localizes there until the metaphase–anaphase transition, after which it is no longer detected (Fig. 1G,I). Imaging of a worm strain expressing GFP:SPDL-1 confirmed this transient localization pattern and also revealed a weak spindle pole localization (Fig. 1H; Supplemental Movie 4). We conclude that SPDL-1 is a transiently kinetochore-localized protein that plays an essential role in chromosome segregation.

SPDL-1 is recruited to kinetochores by the RZZ complex

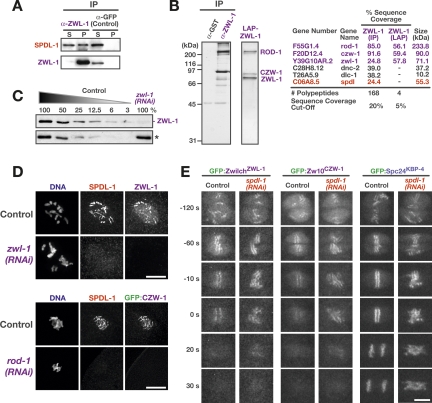

To understand SPDL-1 function at kinetochores, we first sought to determine if it interacts with other known kinetochore components. We immunoprecipitated several inner and outer kinetochore proteins (CENP-AHCP-3, CENP-CHCP-4, MCAKKLP-7, KNL-1, BUB-1, ZwilchZWL-1, NDC-80, HCP-1, CLASPCLS-2) and probed the precipitates for SPDL-1. Only affinity-purified antibodies to ZwilchZWL-1 (Fig. 2C) coprecipitated a detectable amount of SPDL-1 (Fig. 2A). Mass spectrometric analysis of the ZwilchZWL-1 immunoprecipitate (Fig. 2B) confirmed the presence of SPDL-1 and identified the two other subunits of the RZZ complex, ROD-1 and Zw10CZW-1. In contrast, a more stringent tandem purification of ZwilchZWL-1 using the localization and affinity purification (LAP) tag (Cheeseman et al. 2004) isolated only the three RZZ subunits, which could be readily visualized on a silver-stained gel (Fig. 2B), but not SPDL-1, suggesting that SPDL-1 is peripherally associated rather than a stable core subunit of the RZZ complex. Consistent with this idea, gel filtration experiments revealed that endogenous SPDL-1 exhibited the same fractionation profile as recombinant SPDL-1, and that this fractionation behavior was clearly distinct from that of endogenous ZwilchZWL-1 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

SPDL-1 is recruited to the kinetochore by the RZZ complex. (A) SPDL-1 coimmunoprecipitates with ZwilchZWL-1. Worm extracts were depleted of ZwilchZWL-1 using an affinity-purified polyclonal antibody, and the resulting supernatant (S) and pellet (P) was analyzed by immunoblot. Loading of pellet is 20× relative to supernatant. An antibody against GFP was used in the control immunoprecipitation experiment. (B) SPDL-1 associates with the RZZ complex but is not a core subunit. A one-step immunoprecipitation of ZwilchZWL-1 and a stringent two-step isolation of GFPLAP-tagged ZwilchZWL-1 were visualized on a silver-stained gel and analyzed by mass spectrometry as shown on the right. (C) Immunoblotting with the anti-ZwilchZWL-1 antibody detects a 70-kDa band, which is depleted >95% following RNAi. A cross-reacting protein band (*) serves as the loading control. (D) Immunofluorescence images of early embryos stained for SPDL-1 after depletion of ZwilchZWL-1 or ROD-1. Bars, 5 μm. (E) Depletion of SPDL-1 affects neither kinetochore targeting of RZZ subunits nor their rapid disappearance from kinetochores at anaphase onset. Selected frames from time-lapse sequences of embryos expressing GFP:ZwilchZWL-1, GFP:Zw10CZW-1, and GFP:Spc24KBP-4 are shown (see also Supplemental Movies 5, 6). Time is relative to the onset of sister chromatid separation. Bar, 5 μm.

We next analyzed the localization dependencies between SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex. Immunofluorescence and live imaging of GFPLAP fusions to ZwilchZWL-1 and Zw10CZW-1 showed that these two RZZ subunits localize transiently to kinetochores in a fashion essentially identical to SPDL-1 (Fig. 2D,E; Supplemental Movies 5, 6). ROD-1 depletion abolished kinetochore localization of both Zw10CZW-1 and ZwilchZWL-1, suggesting that the three RZZ subunits are likely interdependent for kinetochore targeting (Fig. 2D; data not shown). Depletion of ZwilchZWL-1 or ROD-1 abolished SPDL-1 targeting to kinetochores (Fig. 2D), whereas SPDL-1 depletion did not alter the kinetics of kinetochore localization for either RZZ subunit (Fig. 2E; Supplemental Movies 5, 6). Specifically, rapid disappearance of ZwilchZWL-1 and ROD-1 from kinetochores in early anaphase was observed in both control and spdl-1(RNAi) embryos. This loss occurred prior to mitotic kinetochore disassembly, monitored using the NDC-80 complex subunit Spc24KBP-4, suggesting the existence of a regulatory step controlling RZZ complex removal from kinetochores that is not affected by SPDL-1 depletion. We conclude that SPDL-1 is recruited to kinetochores by the RZZ complex and that both the localization and cell cycle progression-dependent loss of the RZZ complex from kinetochores are independent of SPDL-1.

SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex are dispensable for building the core kinetochore microtubule attachment site

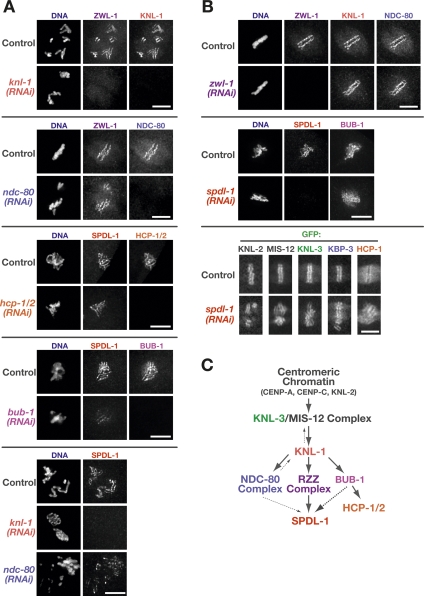

Next we positioned SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex within the established hierarchy for kinetochore assembly. SPDL-1 and RZZ complex localization was dependent on KNL-1 (Fig. 3A), which is required for the localization of multiple outer kinetochore proteins in C. elegans (Desai et al. 2003). Depletion of the CENP-F-like proteins HCP-1 and HCP-2 had no effect on SPDL-1 localization. An intermediate effect on SPDL-1 localization was observed following depletion of NDC-80 or BUB-1; the effect of BUB-1 depletion was consistently more severe than that of NDC-80 depletion. RZZ complex targeting was not affected by any of these depletions (Fig. 3A; A. Essex and A. Desai, unpubl.).

Figure 3.

SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex are dispensable for the formation of the core kinetochore microtubule attachment site. (A) Consequences of outer kinetochore component depletion on the localization of SPDL-1 and ZwilchZWL-1, assayed by immunofluorescence. Bars, 5 μm. (B) Normal localization of outer kinetochore components after depletion of SPDL-1 and ZwilchZWL-1, assayed by immunofluorescence or live imaging of previously characterized GFP-fusions (Cheeseman et al. 2004, 2005; Maddox et al. 2007). Bars, 5 μm. (C) Summary of the dependency analysis for kinetochore targeting of SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex. For each depletion-localization experiment, between five and 10 one-cell or two-cell embryos were examined.

Depletion of SPDL-1 and RZZ subunits had no effect on the localization of KNL-1, KNL-2, KNL-3, MIS-12, NDC-80, the NDC-80 complex subunit Spc25KBP-3, BUB-1, HCP-1, or CLASPCLS-2 (Fig. 3B; data not shown). We conclude that outer kinetochore assembly, including formation of the core microtuble attachment site constituted by the KMN network, does not require either the RZZ complex or SPDL-1 (Fig. 3C).

SPDL-1, like the RZZ complex, is required for a functional spindle checkpoint and Mad2MDF-2 recruitment to unattached kinetochores

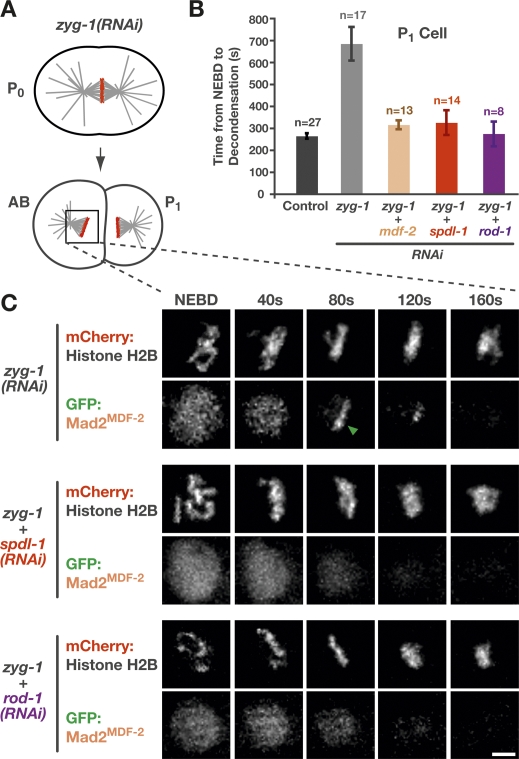

Having established that SPDL-1 functions in close proximity to the RZZ complex, we sought to test if any of the roles ascribed to the RZZ complex require SPDL-1. Work in D. melanogaster and vertebrates has shown that the RZZ complex is required for a functional spindle checkpoint and for localization of the checkpoint protein Mad2 to kinetochores. To probe spindle checkpoint activation in the early C. elegans embryo, we used an assay based on controlled formation of monopolar spindles in the second embryonic division following inhibition of centriole duplication (A. Essex and A. Desai, in prep.). These monopolar spindles elicit a checkpoint-mediated cell cycle delay (Fig. 4B). Depletion of SPDL-1 in cells with monopolar spindles abrogated the delay, demonstrating that the spindle checkpoint requires SPDL-1 (Fig. 4B). The same result was observed for depletions of the RZZ subunit ROD-1. The delay was correlated with transient enrichment of GFP:Mad2MDF-2 on the unattached kinetochores that are distal to the monopole (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Movie 7). Depletion of SPDL-1 or ROD-1 abrogated GFP:Mad2MDF-2 localization to kinetochores of monopolar spindles. We conclude that SPDL-1, like the RZZ complex, is required for spindle checkpoint activation and kinetochore recruitment of GFP:Mad2MDF-2.

Figure 4.

SPDL-1 is required for a functional spindle checkpoint and kinetochore localization of Mad2MDF-2. (A) Perturbation to generate monopolar spindles in the second division and trigger spindle checkpoint activation in C. elegans embryos. ZYG-1 is a kinase required for centriole duplication (O’Connell et al. 2001). In zyg-1(RNAi) embryos, the first division is normal, because two intact centrioles are contributed by sperm that is not affected by RNAi. These centrioles are unable to duplicate, however, resulting in a monopolar spindle in the subsequent division. (B) Average time from NEBD to chromosome decondensation in the P1 cell of a worm strain expressing GFP:histone H2B. ZYG-1 single depletion results in a significant delay that depends on Mad2MDF-2, SPDL-1, and ROD-1. Error bars represent the SEM with a 95% confidence interval. A similar result is observed in the AB cell (data not shown). (C) Stills from a time-lapse sequence of the AB cell monopolar division in a worm strain coexpressing GFP:Mad2MDF-2 and mCherry:histone H2B. In ZYG-1 single depletions, GFP:Mad2MDF-2 accumulates on kinetochores that are distal to the pole (arrow). Codepletion of ZYG-1 with SPDL-1 or ROD-1 prevents kinetochore accumulation of GFP:Mad2MDF-2 (see also Supplemental Movie 7). Bar, 5 μm.

SPDL-1 is required for the recruitment of dynein and dynactin to unattached kinetochores

Dynein/dynactin recruitment to kinetochores has been hypothesized to occur via the dynactin subunit p50/dynamitin, a two-hybrid interactor of Zw10 (Starr et al. 1998). D. melanogaster Spindly (DmSpindly) was reported to be required for dynein but not dynactin targeting to kinetochores, suggesting that dynactin-Zw10 and DmSpindly make independent contributions to dynein localization (Griffis et al. 2007). To test if this is the case in C. elegans, we generated worm strains stably coexpressing mCherry:histone H2B and GFP:fusions of cytoplasmic dynein heavy chainDHC-1 or dynamitinDNC-2. Both fusion proteins localized diffusely to the spindle and the spindle poles in mitosis and significant enrichment at kinetochores over the spindle signal was not evident in unperturbed embryos (data not shown). However, in cells with monopolar spindles, GFP:dynein heavy chainDHC-1 and GFP:dynamitinDNC-2 became prominently enriched at kinetochores (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Movie 8). Both fusion proteins were excluded from the nucleus in interphase and localized to the nuclear periphery opposite the single spindle pole prior to NEBD. After NEBD, both proteins accumulated at kinetochores. This behavior was distinct from that of GFP:KNL-2, a centromeric chromatin protein (Maddox et al. 2007), whose levels at kinetochores did not appreciably change throughout monopolar mitosis (Fig. 5A). GFP:KNL-2 was also present on all sister kinetochores regardless of their orientation relative to the spindle pole. In contrast, the accumulation of both GFP:dynein heavy chainDHC-1 and GFP:dynamitinDNC-2 was restricted to kinetochores that were located on the distal, unattached side of the monopolar spindle. These results indicate that both dynein and dynactin accumulate at unattached kinetochores in C. elegans, as is the case in vertebrates.

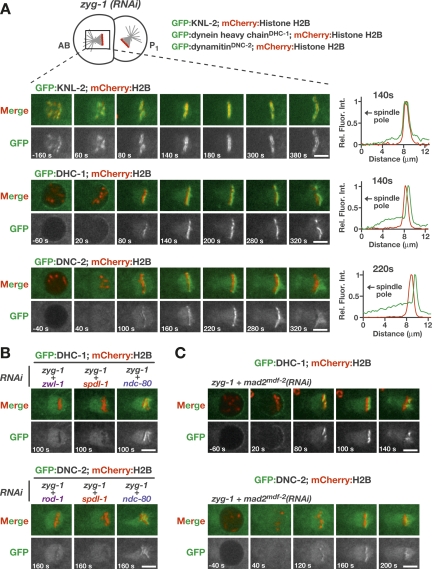

Figure 5.

Localization of dynein and dynactin to kinetochores requires SPDL-1. (A) Unattached kinetochores on second-division monopolar spindles accumulate dynein and dynactin. Strains stably coexpressing GFP:fusions of either KNL-2, full-length dynein heavy chainDHC-1, or dynamitinDNC-2 with mCherry:histone H2B were used to monitor kinetochore localization (see also Supplemental Movie 8). All images are of the AB cell, and the single spindle pole is always to the left. Times are relative to NEBD. Line scans (5 pixels wide; normalized relative to maximum intensity in each channel) indicate the bilaterally symmetric distribution of KNL-2 relative to mCherry:histone H2B, which contrasts with the asymmetric enrichment of DHC-1 and DNC-2 on the chromosomal face pointing away from the single pole. Bars, 5 μm. (B) Kinetochore accumulation of GFP:dynein heavy chainDHC-1 and GFP:dynamitinDNC-2 requires SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex but not NDC-80. For brevity, a single frame is shown for each condition (see also Supplemental Movies 9, 10). Bars, 5 μm. (C) Abrogating the spindle checkpoint by depleting Mad2MDF-2 does not prevent recruitment of GFP:dynein heavy chainDHC-1 or GFP:dynamitinDNC-2 to unattached kinetochores. However, accumulation of the GFP:fusion proteins is limited because of premature mitotic exit. Bars, 5 μm.

We next investigated the role of SPDL-1 in the accumulation of dynein and dynactin on kinetochores of monopolar spindles. We found that both GFP:dynein heavy chainDHC-1 and GFP:dynamitinDNC-2 failed to localize to kinetochores of monopolar spindles in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Movies 9, 10). A similar result was observed following RZZ complex inhibition. In contrast, depletion of NDC-80 did not prevent kinetochore localization of either GFP:dynein heavy chainDHC-1 or GFP:dynamitinDNC-2. Since both SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex are required for the spindle checkpoint-mediated delay elicited by monopolar spindles, we used Mad2MDF-2 depletion to test whether the lack of dynein/dynactin localization was caused by accelerated cell cycle progression. Although their gradual accumulation was cut short by premature mitotic exit, both GFP: dynein heavy chainDHC-1 and GFP:dynamitinDNC-2 were visible at kinetochores in Mad2MDF-2-depleted cells with monopolar spindles (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Movies 9, 10). Of note, none of the perturbations affected the localization of GFP:dynein heavy chainDHC-1 or GFP: dynamitinDNC-2 to the nuclear periphery. We conclude that kinetochore localization of both dynein and dynactin is dependent on SPDL-1.

Depletion of SPDL-1 results in a more severe defect in kinetochore–microtubule attachments than depletion of RZZ complex subunits

SPDL-1 localizes downstream from the RZZ complex and is required for all RZZ complex functions established to date: spindle checkpoint activation, kinetochore recruitment of Mad2, and kinetochore recruitment of dynein/dynactin. These findings predict that chromosome segregation defects in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos should be of similar or reduced severity compared with those observed in embryos depleted of RZZ subunits. We first tested whether depletion of the three RZZ subunits resulted in embryonic lethality, as is the case for depletion of SPDL-1. This analysis confirmed the results of functional genomic studies (Sonnichsen et al. 2005) that the three RZZ subunits are not functionally equivalent. Depletion of Zw10CZW1 causes penetrant sterility of the injected worm, whereas depletion of ROD-1 or ZwilchZWL-1 results in embryonic lethality of its progeny (A. Essex and A. Desai, in prep.). This difference is explained by the requirement of Zw10CZW1, but not ROD-1 or ZwilchZWL-1, for membrane trafficking in the gonad (Anjon Audhya, pers. comm.); defects in trafficking pathways prevent oocyte formation and cause sterility in C. elegans. Consequently, we focused on ROD-1 and ZwilchZWL-1 to specifically analyze RZZ complex function at kinetochores.

We compared the consequences of SPDL-1 depletion with those of ROD-1 or ZwilchZWL-1 depletions in a strain coexpressing GFP:histone H2B, which allowed visual inspection of chromosome alignment and separation, and GFP:γ tubulin, which facilitated spindle pole tracking (Fig. 6A). The latter assay is particularly useful in the one-cell C. elegans embryo, where kinetochore–spindle attachments counteract cortical forces pulling on astral microtubules anchored at the spindle poles; premature pole separation following perturbation of kinetochore-localized proteins is diagnostic of impairment in the formation of load-bearing kinetochore–microtubule attachments, and specific pole separation profiles have proven important in categorizing different types of defects (Oegema et al. 2001; Desai et al. 2003; Cheeseman et al. 2004).

Figure 6.

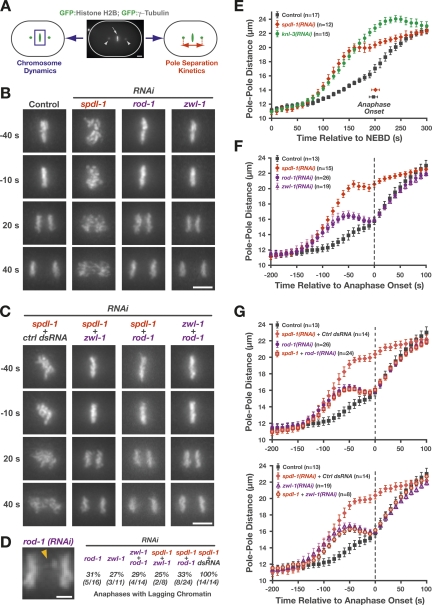

Depletion of SPDL-1 results in a more severe chromosome segregation defect than depletion of ROD-1 or ZwilchZWL-1. (A) Cartoon outlining the two parameters monitored in a strain expressing GFP:histone H2B and GFP:γ-tubulin: chromosome dynamics and kinetics of spindle pole separation. (B) Frames from time-lapse sequences of the first embryonic division, highlighting the differences in chromosome dynamics after depletion of SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex subunits ROD-1 and ZwilchZWL-1 (see also Supplemental Movie 11). The time point 0 sec denotes the onset of sister chromatid separation. Bar, 5 μm. (C) Selected frames from time-lapse sequences of embryos codepleted of RZZ subunits and SPDL-1, which significantly reduces the severe chromosome missegregation phenotype of SPDL-1 single depletions to match that of RZZ subunit single depletions (see also Supplemental Movie 12). Bar, 5 μm. (D) Representative image of anaphase with lagging chromatin in a rod-1(RNAi) one-cell embryo. The frequency of one-cell embryos with lagging anaphase chromatin is indicated for single and double inhibitions involving RZZ subunits and SPDL-1. Bar, 2 μm. (E) Pole separation kinetics in wild-type, spdl-1(RNAi), and knl-3(RNAi) embryos. Images were acquired at 10-sec intervals, and sequences were time-aligned relative to NEBD. Pole–pole distances in the time-aligned sequences were measured, averaged for the indicated number (n) of embryos, and plotted against time. Error bars represent the SEM with a 95% confidence interval. (F) Pole separation kinetics of the perturbations shown in B. Sequences were time-aligned relative to the onset of sister chromatid separation (“Anaphase Onset”). Error bars represent the SEM with a 95% confidence interval. (G) Pole separation kinetics of the perturbations shown in C, demonstrating that double depletions of SPDL-1 and RZZ complex subunits result in a pole separation profile that is indistinguishable from RZZ subunit single depletions. For controls, spdl-1 dsRNA was diluted equally with dsRNA corresponding to the budding yeast gene CTF13 or the C. elegans gene sas-5, which is not required for the first embryonic division (both conditions gave identical results). Error bars represent the SEM with a 95% confidence interval.

Surprisingly, we observed that chromosome segregation and kinetochore–spindle microtubule interaction defects were significantly worse in SPDL-1-depleted embryos than in embryos depleted of RZZ subunits. In spdl-1(RNAi) embryos, which never congressed their chromosomes to a compact metaphase plate (Fig. 6B), the pole separation profile was identical to that of knl-3(RNAi) embryos in which outer kinetochore assembly was prevented (Cheeseman et al. 2004), except for a short period (∼40 sec) prior to sister chromatid separation (Fig. 6E). Although pole separation slowed during this period, suggesting engagement of spindle microtubules by kinetochores, spindles were significantly longer at the time of sister chromatid separation in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos (20 ± 0.5 μm) compared with controls (16.2 ± 0.5 μm). By comparison, the chromosome segregation and premature pole separation defects in rod-1(RNAi) or zwl-1 (RNAi) embryos were markedly less severe (Fig. 6B,F; Supplemental Movie 11). Chromosomes were able to congress and form a metaphase plate, and sister chromatid separation appeared successful in the majority of embryos. A small amount of lagging anaphase chromatin was consistently observed in ∼30% of first divisions in RZZ subunit depletions (Fig. 6D), whereas SPDL-1 depletion resulted in massive chromatin bridges in every first division examined. Pole tracking analysis also revealed a significantly less severe defect in rod-1 or zwl-1(RNAi) embryos compared with spdl-1(RNAi) embryos (Fig. 6F). In RZZ subunit depletions, initial premature pole separation was observed indicating a defect in establishing load-bearing attachments. However, ∼100 sec prior to sister chromatid separation, kinetochores engaged spindle microtubules and spindle length at the time of sister chromatid separation [zwl-1(RNAi), 16 ± 0.3 μm; rod-1(RNAi), 15.6 ± 0.2 μm] was indistinguishable from controls (16.2 ± 0.5 μm).

Both quantitative immunoblotting (Figs. 1F, 2C) and immunofluorescence (Figs. 2D, 3B) indicate that the difference in phenotypic severity described above is unlikely due to reduced depletion efficiency of RZZ subunits relative to SPDL-1. The identical qualitative and quantitative phenotypes of rod-1(RNAi) and zwl-1(RNAi) also argue against this trivial explanation. To further establish that the weaker RZZ inhibition phenotype is not due to partial depletion of the targeted subunits, we codepleted ROD-1 and ZwilchZWL-1. The observed phenotypes in both assays were indistinguishable from single depletions of ROD-1 or ZwilchZWL-1 (Fig. 6C; Supplemental Fig. 2; Supplemental Movie 12).

Thus, RZZ complex inhibition slows but does not prevent formation of load-bearing kinetochore–microtubule attachments and leads to an increase in anaphase lagging chromatin, which is indicative of incorrectly attached kinetochores. Depletion of SPDL-1 results in significantly more severe defects both in the formation of load-bearing kinetochore–microtubule attachments and chromosome segregation. Based on the pole-tracking analysis, the severity of the SPDL-1 inhibition defects closely resembles loss of core microtubule attachment until just prior to anaphase onset.

Coinhibition of SPDL-1 with RZZ subunits results in the less severe RZZ inhibition phenotype

The greater phenotypic severity of SPDL-1 inhibitions noted above may reflect additional nonkinetochore functions of SPDL-1 that are not affected by its displacement from the kinetochore in RZZ subunit depletions. To test this possibility, we codepleted ROD-1 or ZwilchZWL-1 with SPDL-1. In all embryos analyzed (n = 32), the resulting phenotype was indistinguishable from the weaker RZZ subunit depletions (Fig. 6C,G; Supplemental Movie 12). To control for reduced efficacy of RNAi in the double depletions, the SPDL-1 single depletions were repeated after appropriate dilution with control dsRNA. The reduction in phenotypic severity in the double depletions was evident in both the chromosome segregation profile (Fig. 6C) and in the quantitative analysis of spindle pole separation (Fig. 6G). These results are consistent with the assembly epistasis at kinetochores, which showed that SPDL-1 depends on the RZZ complex for localization (Fig. 2), and exclude the possibility that the additional defects observed in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos are due to nonkinetochore functions of SPDL-1. We conclude that the severe defects in SPDL-1-depleted embryos are derived from RZZ complex localized to kinetochores in the absence of associated SPDL-1 and/or dynein/dynactin.

Codepletion of SPDL-1 or RZZ subunits with NDC-80 synergistically recapitulates the “kinetochore-null” phenotype

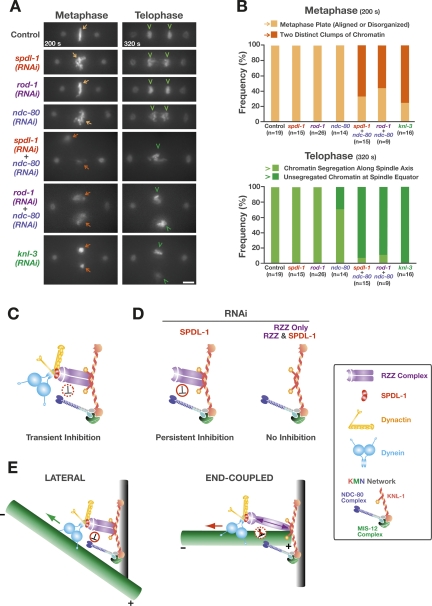

Two microtubule-binding entities are independently targeted to the C. elegans kinetochore via KNL-1: dynein/dynactin (via the RZZ complex and SPDL-1) and the NDC-80 complex, a component of the KMN network (Fig. 3C). In spdl1(RNAi) embryos, just prior to sister chromatid separation, pole separation slowed down significantly and severe chromosome missegregation was observed along the spindle axis (Figs. 1A, 6B). We hypothesized that the eventual slowing of pole separation in spdl-1(RNAi) embryos reflected belated load-bearing attachments made by the NDC-80 complex, while the residual chromosome movements in ndc-80(RNAi) embryos (Supplemental Movie 13) were mediated by kinetochore dynein/dynactin. Codepletion experiments confirmed this view (Fig. 7A,B). While embryos singly depleted of SPDL-1 and NDC-80 were partially successful at congressing their chromosomes to the spindle equator and at segregating sister chromatids in anaphase, double depletions resulted in a phenotype identical to that of knl-3(RNAi) embryos (Supplemental Movie 13), in which outer kinetochore assembly is abolished (Cheeseman et al. 2004). A “kinetochore-null”-like phenotype was also observed in codepletions of NDC-80 with ROD-1 (Supplemental Movie 14). We conclude that it is the absence of the two independently targeted microtubule-interacting components, dynein/dynactin and the NDC-80 complex, that accounts for the synergistic defect. These results further indicate that the reduction in pole separation just prior to anaphase onset and the missegregation of chromosomes observed in SPDL-1-depleted embryos are attributable to the action of the NDC-80 complex.

Figure 7.

Codepletion of SPDL-1 or ROD-1 with NDC-80 recapitulates the “kinetochore-null” phenotype. (A) Frames from time-lapse sequences representing metaphase (200 sec after NEBD) and telophase (320 sec after NEBD). Codepletion of SPDL-1 or ROD-1 with NDC-80 approximates the “kinetochore-null” phenotype of knl-3(RNAi) embryos (see also Supplemental Movies 13 and 14), in which chromosomes of the two pronuclei are often visible as separate clumps at metaphase (arrows), and unsegregated chromatin remains at the spindle equator in telophase (arrowheads). Bar, 5 μm. (B) Percentage of first divisions displaying the chromosome morphologies described in A at 200 sec and 320 sec after NEBD. (C) Schematic summary of the relationship between the RZZ complex, SPDL-1, dynein/dynactin, and the NDC-80 complex. The negative regulation of the KMN network by the RZZ complex, which is transient in the wild-type situation, may be either direct or indirect. (D) Model explaining the difference in phenotypic severity between SPDL-1 and RZZ complex inhibitions. Specifically, we propose that SPDL-1 depletion results in persistent RZZ complex-mediated inhibition of the KMN network (until just prior to anaphase onset), because RZZ complex localization to kinetochores is uncoupled from dynein/dynactin. In RZZ subunit depletions or codepletions of SPDL-1 with RZZ subunits, the inhibitory mechanism is absent, resulting in the weaker phenotype, which reflects loss of dynein contribution to the establishment and orientation of load-bearing attachments. (E) A speculative model for the physiological role of a RZZ complex-mediated inhibition of the KMN network during prometaphase. Dynein/dynactin laterally captures microtubules to accelerate formation of end-coupled attachments of correct geometry. While a microtubule is laterally bound, dynein motility does not experience significant resistance (green arrow); consequently, there is low intrakinetochore tension, and the RZZ complex inhibits the KMN network from binding prematurely to the microtubule, which would interfere with dynein-mediated kinetochore orientation. When the plus end of the microtubule becomes embedded into the outer plate (end-coupled attachment) and provides resistance to dynein/dynactin motility (red arrow), the increased intrakinetochore tension turns off the inhibitory action of the RZZ complex, allowing formation of stable load-bearing attachments.

Discussion

Our analysis of the RZZ complex and SPDL-1, kinetochore-localized components that are sequentially required for dynein/dynactin targeting, gives new insight into how this minus-end-directed motor complex contributes to chromosome segregation. Specifically, the results suggest that kinetochore dynein/dynactin accelerates the formation of load-bearing attachments and provides an important fidelity mechanism, which prevents inappropriate attachments in prometaphase and reduces the missegregation frequency after anaphase onset. This fidelity mechanism likely involves negative regulation of load-bearing kinetochore–microtubule attachments by the RZZ complex. We speculate below that this negative regulation is modulated by dynein/dynactin to ensure the orderly conversion of weak dynein/dynactin-mediated lateral attachments to load-bearing end-coupled attachments during prometaphase.

SPDL-1 targets dynein/dynactin to kinetochores and is required to activate the spindle checkpoint

SPDL-1 targets to the kinetochore immediately downstream from the RZZ complex and is not involved in the assembly of the core kinetochore–microtubule-binding site constituted by the KMN network. Functional analysis showed that SPDL-1 is required for the recruitment of dynein/dynactin and Mad2MDF-2 to unattached kinetochores. The requirement for Mad2MDF-2 targeting explains why SPDL-1 is essential for spindle checkpoint activation. In contrast, D. melanogaster Spindly was shown to be essential for the recruitment of dynein, but not dynactin, to kinetochores, and was found to be dispensable for Mad2 accumulation and spindle checkpoint activation. We also did not observe any abnormalities in cell shape or microtubule organization in SPDL-1-depleted embryos that resembled the defects seen following RNAi of DmSpindly in interphase S2 cells. Preliminary work in human tissue culture cells indicates that human Spindly is similar to C. elegans SPDL-1 in that it is required to recruit both dynein and dynactin to kinetochores, and its inhibition does not result in detectable defects in interphase microtubule organization or cell shape. However, like DmSpindly, the human homolog is not required for Mad2 localization or spindle checkpoint activation (R. Gassmann and A. Desai, unpubl.).

Previous studies have shown that cytoplasmic dynein as well as its accessory factors dynactin and LIS-1 are involved in multiple processes during the first embryonic division of C. elegans, including pronuclear migration, centrosome separation, and bipolar spindle assembly (Gonczy et al. 1999; Cockell et al. 2004; Schmidt et al. 2005; O’Rourke et al. 2007). All of these processes are unaffected following SPDL-1 depletion, indicating that SPDL-1 does not globally control dynein function.

The C. elegans RZZ complex

The close relationship between SPDL-1 and the RZZ homologs led us to functionally characterize the RZZ complex in C. elegans. The RZZ complex has been studied primarily in D. melanogaster with recent contributions from vertebrate systems (Karess 2005). Our results in C. elegans confirm that ROD-1, ZwilchZWL-1, and Zw10CZW-1 function as a complex that localizes transiently to kinetochores from NEBD until the onset of anaphase. The RZZ complex localizes to the outer kinetochore downstream from KNL-1 and, like SPDL-1, is not required for kinetochore targeting of the NDC-80 complex. In vertebrates, the coiled-coil protein Zwint acts as an intermediary between KNL-1 and the RZZ complex, but Zwint-like molecules have not been identified in C. elegans or D. melanogaster (Starr et al. 2000; Cheeseman et al. 2004; Kops et al. 2005). The two known roles of the RZZ complex, recruitment of dynein/dynactin to unattached kinetochores and activation of the spindle checkpoint through kinetochore targeting of Mad2, are conserved in C. elegans.

RNAi in C. elegans suggests that Zw10CZW-1, but not ROD-1 or ZwilchZWL-1, has an additional nonkinetochore function in membrane trafficking, as previously reported in vertebrates (Hirose et al. 2004). This difference between the RZZ subunits raises a cautionary note about interpreting Zw10 perturbations strictly in terms of kinetochore function, and we were careful to focus on ROD-1 and ZwilchZWL-1 as targets to specifically inhibit RZZ complex activity at kinetochores.

Implications of C. elegans RZZ complex analysis for the role of dynein/dynactin at the kinetochore

Chromosome movement

Dynein/dynactin and the microtubule-binding NDC-80 complex are independently targeted to kinetochores downstream from KNL-1. While the NDC-80 complex is required to make load-bearing kinetochore–microtubule attachments, its inhibition does not result in a “kinetochore-null” phenotype as clear residual chromosome movements are observed (Desai et al. 2003). Such Ndc80 complex-independent movements have also been described in vertebrate cells and dynein/dynactin has been implicated as their source (McCleland et al. 2004; DeLuca et al. 2005; Vorozhko et al. 2008). Our finding that double depletions of NDC-80 with either ROD-1 or SPDL-1 synergistically recapitulate the “kinetochore-null” phenotype is consistent with the conclusion that both of these microtubule-binding activities contribute to chromosome–spindle microtubule interactions downstream from KNL-1.

Kinetics of load-bearing attachment formation

In the absence of the NDC-80 complex, kinetochore-localized dynein/dynactin is insufficient to generate load-bearing attachments that can oppose the effects of aster-based cortical pulling forces during chromosome alignment. In RZZ complex-inhibited embryos, formation of load-bearing attachments occurs, but is delayed. This result suggests that kinetochore-localized dynein/dynactin accelerates the formation of NDC-80 complex dependent end-coupled attachments. We speculate that this kinetic acceleration is due to the ability of dynein/dynactin to efficiently collect microtubules that pass by the kinetochore. Such microtubules would remain laterally associated with the kinetochore until their dynamic plus ends are close enough to be integrated into the outer plate by the KMN network. Importantly, in RZZ complex-inhibited embryos, despite the kinetic defect in forming load-bearing attachments, spindles always reached wild-type length at anaphase onset and had a tightly aligned metaphase plate. Thus, kinetochore dynein/dynactin is dispensable for end-coupled load-bearing attachments, but it accelerates their formation in early prometaphase.

Attachment geometry

In addition to the kinetic effect on the formation of load-bearing attachments, RZZ complex inhibitions revealed an increased frequency of lagging chromatin during anaphase. Importantly, depletion of either Mad1MDF-1 or Mad2MDF-2, both essential components of the spindle checkpoint, does not have any deleterious effects on chromosome segregation in the first embryonic division (A. Essex and A. Desai, in prep.). Thus, the lack of a spindle checkpoint-mediated cell cycle delay cannot explain the chromosome missegregation observed in RZZ complex inhibitions. This finding is similar to the situation in D. melanogaster, where mad2-null mutants are reported to have little or no chromosome segregation defects, while the signature phenotype of zw10- and rod-null mutants is lagging anaphase chromatin (Karess and Glover 1989; Williams et al. 1992; Buffin et al. 2007). Since RZZ complex-inhibited embryos have no noticeable defects in chromosome condensation, it is likely that the chromatin bridges in anaphase are caused by incorrect merotelic attachments, where a single kinetochore is connected to both poles (Cimini et al. 2003). We propose that a major role of kinetochore dynein/dynactin is to prevent the generation of such maloriented kinetochores in early prometaphase, when kinetochore–microtubule interactions are first established. When an unattached sister kinetochore binds laterally to an astral microtubule, the minus-end-directed motility of dynein/dynactin would provide a force that orients the kinetochore toward the spindle pole at which that particular microtubule originates, thereby decreasing the probability that the same kinetochore captures a microtubule from the opposite pole. Thus, dynein/dynactin would ensure correct attachment geometry by forcing sister kinetochores to face opposite poles.

Transient inhibition of load-bearing kinetochore–microtubule attachments by the RZZ complex: a mechanism to coordinate the transition from lateral to end-coupled attachments?

The RZZ complex and SPDL-1 are equivalently required for both dynein/dynactin targeting to kinetochores and spindle checkpoint activation. Yet, the consequences of their inhibition are strikingly different. Pole tracking analysis revealed that the consequences of inhibiting SPDL-1 are indistinguishable from complete loss of load-bearing attachments until just prior to anaphase onset. In contrast, in the RZZ complex inhibitions, after a slight delay, kinetochore–microtubule attachments eventually bear load equally well as those of unperturbed embryos, resulting in wild-type spindle length at anaphase onset.

This comparison reveals that following SPDL-1 inhibition there is a significant defect in formation of KMN network-mediated load-bearing attachments. The defect is attributable to the presence of the RZZ complex at kinetochores, as coinhibition of SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex reduces the phenotypic severity to match that of inhibiting the RZZ complex alone. This observation indicates that the RZZ complex negatively regulates KMN network activity and that this negative regulation persists for most of prometaphase in the absence of SPDL-1 (Fig. 7C,D). The RZZ complex may inhibit the KMN network either directly or via other regulators of KMN network function. Aurora B kinase is known to negatively regulate the microtubule-binding activity of the Ndc80 complex (Cheeseman et al. 2006; DeLuca et al. 2006). In preliminary work using a temperature-sensitive Aurora BAIR-2 mutant, coinhibition of Aurora B did not reduce the severity of the chromosome segregation defect following SPDL-1 depletion (R. Gassmann and A. Desai, unpubl.), suggesting that the RZZ complex does not regulate the KMN network through Aurora B. In the absence of the RZZ complex from kinetochores, the mechanism for negatively regulating KMN network activity is no longer present, explaining why coinhibition of SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex quantitatively reduces the phenotypic severity to match that of the RZZ complex alone (Fig. 7D).

We propose that the physiological function of the regulatory link between the RZZ complex and the KMN network is to ensure a coordinated transition from transient lateral attachments made by dynein, which accelerate formation of end-coupled attachments of correct geometry, to stable load-bearing end-coupled attachments that do the job of chromosome segregation. In this model, RZZ complex inhibition of the KMN network is modulated by the microtubule minus-end-directed motility of dynein/dynactin, which is linked to the outer kinetochore via SPDL-1 and the RZZ complex (Fig. 7E). When dynein/dynactin is laterally attached to a microtubule that extends past the kinetochore, the RZZ complex is under low tension and negatively regulates the microtubule-binding activity of the KMN network. This prevents the KMN network from tightly binding to a microtubule extending past the kinetochore that has been captured by dynein/dynactin. When dynein/dynactin translocation toward the microtubule minus end is met with resistance due to the microtubule plus end being embedded in the kinetochore outer plate, the RZZ complex is placed under tension and inhibition of the KMN network is relieved. We envision that such a feedback mechanism prevents premature lateral binding of the KMN network to microtubules, which would interfere with dynein-mediated kinetochore orientation and increase the likelihood of forming incorrect merotelic attachments.

In summary, our results reveal a new mechanism regulating kinetochore–microtubule attachments that involves the RZZ complex and is likely to be modulated by dynein/dynactin activity. We speculate on the underlying reason for why such a regulatory mechanism would be necessary for the fidelity of chromosome segregation. This mechanism is likely to be integrated with spindle checkpoint signaling that also requires the RZZ complex in all metazoans.

Materials and methods

Worm strains and antibodies

Worm strains used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table 1. For worm GFPLAP fusions of SPDL-1, ZWL-1, CZW-1, and MDF-2, the genomic locus was cloned into pIC26 (Cheeseman et al. 2004); the genomic locus of DNC-2 was cloned into pAZ132 (Praitis et al. 2001). For DHC-1, the start codon was replaced with GFP by recombineering a full-length dhc-1 fosmid clone (details will be described elsewhere). All constructs were integrated into the DP38 strain [unc-119(ed3)] using microparticle bombardment (Praitis et al. 2001) with a PDS-1000/He Biolistic Particle Delivery System (Bio-Rad), and mCherry: histone H2B was subsequently introduced by mating (Green et al. 2008). Affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies against full-length SPDL-1 and ZwilchZWL-1 were generated as described previously (Desai et al. 2003).

RNAi

L4 worms were injected with dsRNA (Supplemental Table 2) prepared as described previously (Oegema et al. 2001) and incubated for 48 h at 20°C. For double depletions, dsRNAs were mixed to obtain equal concentrations of ≥0.75 mg/mL for each dsRNA.

Immunofluorescence

For stainings with the anti-SPDL-1 antibody, embryos were fixed for 5 min in 3% paraformaldehyde as detailed previously (Howe et al. 2001). Immunofluorescence for other antibodies and microscopy was performed as described in Oegema et al. (2001) and Cheeseman et al. (2004), respectively. All antibodies used were directly labeled with fluorescent dyes (Cy2, Cy3, or Cy5; Amersham Biosciences).

Live imaging

Time-lapse movies of worm strain TH32 (coexpressing GFP: histone H2B and GFP:γ-tubulin) (Oegema et al. 2001) were acquired at 21°C on a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope using a charge-coupled device camera (Orca-ER; Hamamatsu Photonics) at 2 × 2 binning, and a 60× 1.4 NA Plan Apochromat objective. Acquisition parameters, shutters, and focus were controlled by MetaMorph software (MDS Analytical Technologies). Quantitative analysis of spindle pole elongation was performed using a MetaMorph algorithm (Desai et al. 2003). Movies of strain TH32 for the spindle checkpoint assay were recorded at 18°C on a DeltaVision microscope (Applied Precision) equipped with a CoolSnap charge-coupled device camera (Roper Scientific) at 2 × 2 binning and a 100× NA 1.3 U-planApo objective (Olympus). Imaging of all other worm strains was performed at 21°C on a spinning disc confocal head (McBain Instruments) mounted on an inverted Nikon TE2000e microscope equipped with a 60× 1.4 NA Plan Apochromat lens (Nikon), a krypton-argon 2.5 W water-cooled laser (Spectra-Physics), and a charge-coupled device camera (iXon; Andor Technology, or Orca-ER; Hamamatsu Photonics). Acquisition parameters, shutters, and focus were controlled by MetaMorph software. Imaging conditions for individual strains are listed in Supplemental Table 3.

Immunoprecipitations, LAP purifications, and mass spectrometry

Immunoprecipitations were conducted on high-speed supernatant from adult worms as described previously (Cheeseman et al. 2004). For Western blotting, proteins were eluted from the antibody–Protein A resin with sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.8, 15% [w/v] sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, 3% SDS) for 15 min at 70°C. For mass spectrometric analysis, the elution was performed with 8 M urea in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5). LAP purification of ZwilchZWL-1 and mass spectrometry were conducted as described previously (Cheeseman et al. 2001, 2004). Tandem mass spectra were searched against the most recent version of the predicted C. elegans proteins (Wormpep111).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ana Carvalho, Andrew Holland, and Alex Dammermann for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a National Science Foundation of Switzerland fellowship (to R.G.), the UCSD Genetics Training Grant (to A.E.), a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society fellowship (to S.O.), a Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation fellowship (to P.M.), grants from the NIH to A.D. (GM074215) and to B.B (GM49869), a Scholar Award from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation to A.D. (DRS 38-04), and funding from the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research to A.D. and K.O.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1687508.

References

- Basto R., Gomes R., Karess R.E. Rough deal and Zw10 are required for the metaphase checkpoint in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:939–943. doi: 10.1038/35046592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffin E., Lefebvre C., Huang J., Gagou M.E., Karess R.E. Recruitment of Mad2 to the kinetochore requires the Rod/Zw10 complex. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:856–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffin E., Emre D., Karess R.E. Flies without a spindle checkpoint. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:565–572. doi: 10.1038/ncb1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan G.K., Jablonski S.A., Starr D.A., Goldberg M.L., Yen T.J. Human Zw10 and ROD are mitotic checkpoint proteins that bind to kinetochores. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:944–947. doi: 10.1038/35046598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman I.M., Brew C., Wolyniak M., Desai A., Anderson S., Muster N., Yates J.R., Huffaker T.C., Drubin D.G., Barnes G. Implication of a novel multiprotein Dam1p complex in outer kinetochore function. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:1137–1145. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman I.M., Niessen S., Anderson S., Hyndman F., Yates J.R., Oegema K., Desai A. A conserved protein network controls assembly of the outer kinetochore and its ability to sustain tension. Genes & Dev. 2004;18:2255–2268. doi: 10.1101/gad.1234104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman I.M., MacLeod I., Yates J.R., Oegema K., Desai A. The CENP-F-like proteins HCP-1 and HCP-2 target CLASP to kinetochores to mediate chromosome segregation. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:771–777. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman I.M., Chappie J.S., Wilson-Kubalek E.M., Desai A. The conserved KMN network constitutes the core microtubule-binding site of the kinetochore. Cell. 2006;127:983–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimini D., Moree B., Canman J.C., Salmon E.D. Merotelic kinetochore orientation occurs frequently during early mitosis in mammalian tissue cells and error correction is achieved by two different mechanisms. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:4213–4225. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockell M.M., Baumer K., Gonczy P. lis-1 is required for dynein-dependent cell division processes in C. elegans embryos. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:4571–4582. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J.G., Dong Y., Hergert P., Strauss J., Hickey J.M., Salmon E.D., McEwen B.F. Hec1 and nuf2 are core components of the kinetochore outer plate essential for organizing microtubule attachment sites. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:519–531. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J.G., Gall W.E., Ciferri C., Cimini D., Musacchio A., Salmon E.D. Kinetochore microtubule dynamics and attachment stability are regulated by Hec1. Cell. 2006;127:969–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A., Rybina S., Muller-Reichert T., Shevchenko A., Shevchenko A., Hyman A., Oegema K. KNL-1 directs assembly of the microtubule-binding interface of the kinetochore in C. elegans. Genes & Dev. 2003;17:2421–2435. doi: 10.1101/gad.1126303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonczy P., Pichler S., Kirkham M., Hyman A.A. Cytoplasmic dynein is required for distinct aspects of MTOC positioning, including centrosome separation, in the one cell stage Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:135–150. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R.A., Audhya A., Pozniakovsky A., Dammermann A., Pemble H., Monen J., Portier N., Hyman A., Desai A., Oegema K. Expression and imaging of fluorescent proteins in the C. elegans gonad and early embryo. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;85:179–218. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)85009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffis E.R., Stuurman N., Vale R.D. Spindly, a novel protein essential for silencing the spindle assembly checkpoint, recruits dynein to the kinetochore. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:1005–1015. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose H., Arasaki K., Dohmae N., Takio K., Hatsuzawa K., Nagahama M., Tani K., Yamamoto A., Tohyama M., Tagaya M. Implication of ZW10 in membrane trafficking between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. EMBO J. 2004;23:1267–1278. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe M., McDonald K.L., Albertson D.G., Meyer B.J. HIM-10 is required for kinetochore structure and function on Caenorhabditis elegans holocentric chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1227–1238. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell B.J., McEwen B.F., Canman J.C., Hoffman D.B., Farrar E.M., Rieder C.L., Salmon E.D. Cytoplasmic dynein/dynactin drives kinetochore protein transport to the spindle poles and has a role in mitotic spindle checkpoint inactivation. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:1159–1172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karess R. Rod–Zw10–Zwilch: A key player in the spindle checkpoint. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karess R.E., Glover D.M. rough deal: A gene required for proper mitotic segregation in Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:2951–2961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline-Smith S.L., Sandall S., Desai A. Kinetochore–spindle microtubule interactions during mitosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kops G.J., Kim Y., Weaver B.A., Mao Y., McLeod I., Yates J.R., Tagaya M., Cleveland D.W. ZW10 links mitotic checkpoint signaling to the structural kinetochore. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:49–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Yu W., Liang Y., Zhu X. Kinetochore dynein generates a poleward pulling force to facilitate congression and full chromosome alignment. Cell Res. 2007;17:701–712. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox P.S., Hyndman F., Monen J., Oegema K., Desai A. Functional genomics identifies a Myb domain-containing protein family required for assembly of CENP-A chromatin. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:757–763. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleland M.L., Kallio M.J., Barrett-Wilt G.A., Kestner C.A., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D.F., Gorbsky G.J., Stukenberg P.T. The vertebrate Ndc80 complex contains Spc24 and Spc25 homologs, which are required to establish and maintain kinetochore–microtubule attachment. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A., Salmon E.D. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:379–393. doi: 10.1038/nrm2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas R.B. The forces that move chromosomes in mitosis. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1988;17:431–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.17.060188.002243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell K.F., Caron C., Kopish K.R., Hurd D.D., Kemphues K.J., Li Y., White J.G. The C. elegans zyg-1 gene encodes a regulator of centrosome duplication with distinct maternal and paternal roles in the embryo. Cell. 2001;105:547–558. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oegema K., Desai A., Rybina S., Kirkham M., Hyman A.A. Functional analysis of kinetochore assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1209–1226. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke S.M., Dorfman M.D., Carter J.C., Bowerman B. Dynein modifiers in C. elegans: Light chains suppress conditional heavy chain mutants. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praitis V., Casey E., Collar D., Austin J. Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2001;157:1217–1226. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder C.L., Alexander S.P. Kinetochores are transported poleward along a single astral microtubule during chromosome attachment to the spindle in newt lung cells. J. Cell Biol. 1990;110:81–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoian M.S., Goldberg M.L., Rieder C.L. The rate of poleward chromosome motion is attenuated in Drosophila zw10 and rod mutants. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:948–952. doi: 10.1038/35046605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaerou F., Aguilera I., Saunders R., Kane N., Blottiere L., Karess R. The rough deal protein is a new kinetochore component required for accurate chromosome segregation in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:3757–3768. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.21.3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaerou F., Starr D.A., Piano F., Papoulas O., Karess R.E., Goldberg M.L. The ZW10 and Rough Deal checkpoint proteins function together in a large, evolutionarily conserved complex targeted to the kinetochore. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:3103–3114. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.17.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D.J., Rose D.J., Saxton W.M., Strome S. Functional analysis of cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain in Caenorhabditis elegans with fast-acting temperature-sensitive mutations. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:1200–1212. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.A., Baker B.S., Gatti M. Mutations in genes encoding essential mitotic functions in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1985;110:647–670. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.4.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnichsen B., Koski L.B., Walsh A., Marschall P., Neumann B., Brehm M., Alleaume A.M., Artelt J., Bettencourt P., Cassin E., et al. Full-genome RNAi profiling of early embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2005;434:462–469. doi: 10.1038/nature03353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr D.A., Williams B.C., Hays T.S., Goldberg M.L. ZW10 helps recruit dynactin and dynein to the kinetochore. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:763–774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr D.A., Saffery R., Li Z., Simpson A.E., Choo K.H., Yen T.J., Goldberg M.L. HZwint-1, a novel human kinetochore component that interacts with HZW10. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:1939–1950. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehman S.A., Chen Y., McKenney R.J., Vallee R.B. NudE and NudEL are required for mitotic progression and are involved in dynein recruitment to kinetochores. J. Cell Biol. 2007;178:583–594. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle M.A., Taylor S.S. Cenp-F links kinetochores to Ndel1/Nde1/Lis1/dynein microtubule motor complexes. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1173–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorozhko V.V., Emanuele M.J., Kallio M.J., Stukenberg P.T., Gorbsky G.J. Multiple mechanisms of chromosome movement in vertebrate cells mediated through the Ndc80 complex and dynein/dynactin. Chromosoma. 2008;117:169–179. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R.R., Al-Bassam J., Harrison S.C. The Ndc80/HEC1 complex is a contact point for kinetochore–microtubule attachment. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:54–59. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B.C., Goldberg M.L. Determinants of Drosophila zw10 protein localization and function. J. Cell Sci. 1994;107:785–798. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B.C., Karr T.L., Montgomery J.M., Goldberg M.L. The Drosophila l(1)zw10 gene product, required for accurate mitotic chromosome segregation, is redistributed at anaphase onset. J. Cell Biol. 1992;118:759–773. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.4.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B.C., Li Z., Liu S., Williams E.V., Leung G., Yen T.J., Goldberg M.L. Zwilch, a new component of the ZW10/ROD complex required for kinetochore functions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:1379–1391. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik E., Basto R., Serr M., Scaerou F., Karess R., Hays T. Kinetochore dynein: Its dynamics and role in the transport of the Rough deal checkpoint protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:1001–1007. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Tulu U.S., Wadsworth P., Rieder C.L. Kinetochore dynein is required for chromosome motion and congression independent of the spindle checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:973–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]