Abstract

Promoter recognition by TATA-binding protein (TBP) is an essential step in the initiation of RNA polymerase II (pol II) mediated transcription. Genetic and biochemical studies in yeast have shown that Mot1p and NC2 play important roles in inhibiting TBP activity. To understand how TBP activity is regulated in a genome-wide manner, we profiled the binding of TBP, NC2, Mot1p, TFIID, SAGA, and pol II across the yeast genome using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)–chip for cells in exponential growth and during reprogramming of transcription. We find that TBP, NC2, and Mot1p colocalize at transcriptionally active pol II core promoters. Relative binding of NC2α and Mot1p is higher at TATA promoters, whereas NC2β has a preference for TATA-less promoters. In line with the ChIP–chip data, we isolated a stable TBP–NC2–Mot1p–DNA complex from chromatin extracts. ATP hydrolysis releases NC2 and DNA from the Mot1p–TBP complex. In vivo experiments indicate that promoter dissociation of TBP and NC2 is highly dynamic, which is dependent on Mot1p function. Based on these results, we propose that NC2 and Mot1p cooperate to dynamically restrict TBP activity on transcribed promoters.

Keywords: TATA-box-binding protein, NC2, Mot1, TFIID, SAGA, genome-wide location analysis

Transcription regulation in eukaryotes is a dynamic process that involves the coordinated action of numerous protein complexes. The TATA-box-binding protein (TBP) is an essential component of RNA polymerase II (pol II) transcription complexes. The activity of TBP is subjected to positive regulation by the TFIID and SAGA complexes, which have overlapping functions in TBP recruitment and transcription regulation (Lee et al. 2000). TBP can be regulated negatively by the Mot1p and NC2 complexes (Pugh 2000). Mot1p is a conserved member of the Snf2p ATPase family and was initially identified in genetic screens as a negative regulator of transcription (Davis et al. 1992). Mot1p forms a high-affinity heterodimer with TBP both on and off DNA (Davis et al. 1992; Poon et al. 1994; Gumbs et al. 2003). Upon ATP hydrolysis Mot1p can disrupt a TBP–DNA complex to repress transcription in vitro (Auble et al. 1994). Interestingly, Mot1p seems to alter the DNA-binding specificity of TBP (Gumbs et al. 2003). The negative cofactor NC2 can also form a high-affinity complex with DNA-bound TBP (Meisterernst et al. 1991). NC2 does not bind efficiently to TBP in the absence of DNA. In yeast NC2 consists of the Bur6p (NC2α) and Ydr1p (NC2β) proteins. NC2 binding to TBP blocks preinitiation complex (PIC) assembly by preventing the association of TFIIA and TFIIB (Inostroza et al. 1992; Goppelt et al. 1996). Recent work indicates that NC2 induces dynamic changes in the TBP–DNA complex, allowing TBP reallocation from TATA-box sequences (Schluesche et al. 2007). Several observations indicate that NC2 and Mot1p overlap in function. In a genetic screen it was shown that mutation of the MOT1 (BUR3) and BUR6 genes can bypass the upstream activating sequence (UAS) of the SUC2 gene (Prelich and Winston 1993). In addition, MOT1 and BUR6 interact genetically, as certain mutations in NC2α suppress the bur phenotype of mot1-301 (Wang et al. 2006). Growth defects, caused by depletion of NC2 or Mot1p, can be suppressed by pol II mutants (Peiro-Chova and Estruch 2007).

Whereas in vitro experiments have shown that in yeast NC2 and Mot1p are general repressors of transcription, several lines of evidence indicate positive roles for these factors. Microarray mRNA expression profiles of NC2 and mot1 mutants identified genes that were repressed, but also genes that were positively regulated by these factors (Geisberg et al. 2001; Andrau et al. 2002; Cang and Prelich 2002; Dasgupta et al. 2002). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis indicated that NC2 and Mot1p can localize to actively transcribed genes (Andrau et al. 2002; Creton et al. 2002; Geisberg et al. 2002). In addition, ChIP–reChIP experiments indicated that Mot1p, TFIIB, and RNA pol II can co-occupy heat stress-induced promoters (Geisberg and Struhl 2004). Also, genetic interactions between mot1 mutants with spt8 and spt3 deletion strains suggest that there is a functional link between transcriptional activators like SAGA and Mot1p (Collart 1996; Madison and Winston 1997; van Oevelen et al. 2005). A recent report indicates that NC2 can also stimulate PIC complex formation at selective promoters (Masson et al. 2008).

It is clear that Mot1p, NC2, SAGA, and TFIID can regulate TBP distribution and activity. A detailed view of how these factors cooperate is lacking, however. We addressed this by profiling the genome-wide localization of TBP, NC2, and Mot1p for yeast cells in exponential growth and during transcriptional reprogramming in a shift from high to low glucose. To examine the interplay with TFIID, SAGA, and transcription, the binding profiles of Taf1p (TFIID), Spt20p (SAGA), and Rpb3p (pol II) were also determined. Our data indicate that there is substantial overlap between the TBP, NC2, and Mot1p binding profiles. The binding of NC2 and Mot1p also correlates with SAGA and TFIID occupancy. Furthermore, NC2 and Mot1p binding show a strong correlation with active transcription. During the low glucose shift, the NC2α and NC2β subunits are differentially localized. We isolated a stable NC2–Mot1p–TBP–DNA complex, which is disrupted upon ATP hydrolysis. Based on these results, we propose that Mot1p and NC2 act in a cooperative mechanism to regulate the transcriptional output of active genes.

Results

Genomic binding profiles of TBP, NC2α, NC2β, and Mot1p correlate with active transcription

In trying to understand the functional interaction between NC2 and Mot1p, we profiled their genomic binding across the yeast genome and compared these with TBP binding. In addition, we examined the genomic distribution of Taf1p and Spt20p. Taf1p is the largest subunit of the TFIID complex, which consists of TBP and 13–14 evolutionarily conserved TBP-associated factors (TAFs) (Sanders and Weil 2000). Both TAF-dependent and TAF-independent forms of TBP have been detected on active promoters (Kuras et al. 2000; Li et al. 2000). TFIID shares some of its TAF subunits with SAGA/SLIK coactivator complexes (Grant et al. 1998). Spt20p is a core subunit of this multifunctional histone acetyl transferase complex, which coactivates transcription through different mechanisms (Timmers and Tora 2005; Daniel and Grant 2007). To correlate the genomic distribution of these factors to the transcription state of genes we also included the Rpb3p subunit of pol II. Two biological replicates were processed for ChIP analysis. Cross-linked protein–DNA complexes were recovered via a biotin tag engineered at the N- or C-terminal end of the proteins (van Werven and Timmers 2006). High-density oligonucleotide arrays covering the whole Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome and a T7 RNA polymerase-based linear amplification method were used to determine genomic locations (van Bakel et al. 2008). After quantification and normalization, the binding profiles were corrected for nonspecific signals generated by a ChIP–chip experiment of an untagged yeast strain.

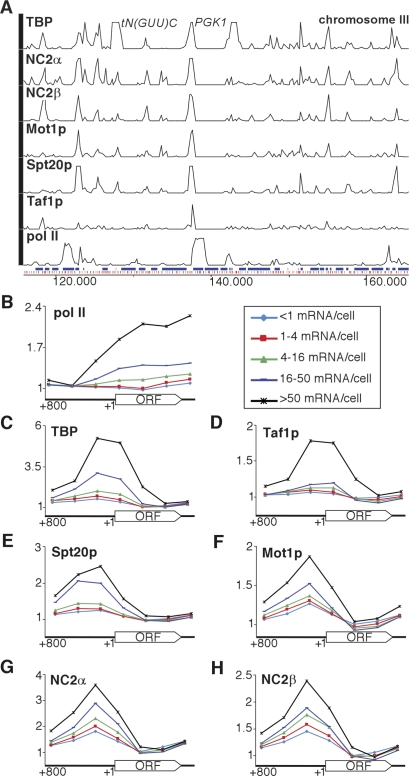

An overview plot of a part of chromosome III illustrates that NC2 binding overlaps with TBP on the promoters of pol II transcribed genes (Fig. 1A). Although Mot1p ChIP signals were lower in general, we observe a strong overlap of the binding profiles of Mot1p with NC2 and TBP. In contrast, Taf1p binding overlaps with only a subset of TBP-binding sites. However, these sites also contain NC2 and Mot1p. TBP-binding peaks were observed on genes corresponding to tRNAs and snoRNAs (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. 1). In contrast, little binding of Mot1p, NC2, Taf1p, or Spt20p is found at these RNA pol III-transcribed genes (Supplemental Fig. 1). For subsequent analysis, we excluded binding signals within 2 kb of pol III transcribed genes, as the strong TBP binding in these regions would interfere with the analysis of adjacent pol II transcribed genes. The resulting data set contains 90% of all pol II transcribed genes (5865 in total).

Figure 1.

ChIP–chip analysis of TBP, NC2α, NC2β, TBP, Mot1p, Taf1p, Spt20p, and pol II and the correlation to gene expression levels. (A) Overview plot of a part of chromosome III (115–165 kb) of the different binding profiles is shown. The locations of the oligos on the array are indicated in red and gene annotations in blue. The binding profiles are presented on the same scale (one- to fourfold over background). The location of the promoters for the pol II-transcribed PGK1, and for the pol III-transcribed tN(GUU)C genes are indicated at the top of the figure. Please note that as expected (Kuras et al. 2000) low levels of Taf1p can be detected at the TAF-independent PGK1 promoter. (B–H) Average binding analysis of pol II, TBP, Taf1p, Spt20p, Mot1p, NC2α, and NC2β for gene groups with <1, 1–4, 4–16, 16–50, or >50 mRNA copies per cell. Average binding profiles were determined for regions in the ORF (5′ end, middle, and 3′ end), promoter (fragments: −800/−551, −550/−301 or −300/−50 relative to the ATG start codon) and 3′ end region (200 bp downstream from the ORF).

To compare the genomic binding profiles of the different factors to the transcriptional state of pol II genes, we selected gene clusters ranging from low to high mRNA expression levels (Holstege et al. 1998; Pokholok et al. 2005). For each cluster we computed the average binding profile for the factor to the ORF (5′ end, middle, and 3′ end), promoter (fragments: −800/−551, −550/−301, or −300/−50 relative to the ATG start codon) and 3′ end region (200 bp downstream from the ORF). As expected, pol II localizes mainly to the ORF and 3′ end of genes and pol II binding strongly correlated with mRNA levels (Fig. 1B). TBP binding peaks at the −300/−50 region encompassing the core promoter and at the 5′ end of the ORF. Similar to pol II, TBP binding correlates well with the transcription rate (Fig. 1C). Taf1p (Fig. 1D) and Spt20p (Fig. 1E) display similar binding patterns as TBP, but we noted that Spt20p binding was shifted upstream. Similar to TBP, binding of Mot1p (Fig. 1F) and the NC2α and NC2β subunits (Fig. 1G,H) peaks at the core promoter region (−300/−50). Surprisingly, the binding of these negative regulators of TBP shows a strong positive correlation with mRNA expression levels. In conclusion, our genome localization data indicate that Mot1p and NC2 localize mostly to promoters of actively transcribed genes.

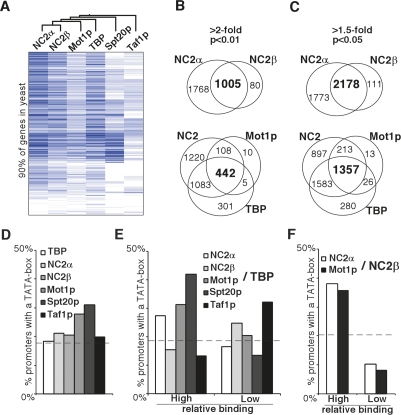

Genomic binding profiles of TBP, NC2α, NC2β, and Mot1p are overlapping

To investigate the relation between the TBP regulatory factors in more detail we performed an unsupervised hierarchical clustering on the average promoter binding profiles of TBP, NC2α, NC2β, Mot1p, Spt20p, and Taf1p (Fig. 2A). This reveals that the binding profiles of the NC2 subunits closely cluster together with Mot1p, but not with Taf1p or Spt20p. To examine the overlap in promoter binding of NC2, Mot1p, and TBP, two different binding cutoffs (more than twofold binding over input and a P-value <0.01 [Fig. 2B] and >1.5-fold binding over input and a P-value <0.05 [Fig. 2C]) were applied. When applying the stringent cutoff (Fig. 2B), NC2α localizes to almost 2800 promoters. In the less stringent statistical analysis, NC2α binds to ∼3900 promoters (Fig. 2C). By both criteria NC2β predominantly localizes to NC2α-bound promoters. Next, we compared Mot1p and TBP binding to promoters that carried either NC2α or NC2β. Almost all of Mot1p (>97%) and most of TBP-bound promoters (>83%) overlap with NC2-bound promoters. The outcome of this is comparable when NC2α and NC2β are analyzed separately (Supplemental Fig. 2A,B). In addition, Taf1p and Spt20p binding profiles display a substantial overlap with NC2-, Mot1p-, and TBP-bound promoters (Supplemental Fig. 2C,D).

Figure 2.

The genomic binding profiles of NC2 and Mot1p overlap. (A) Cluster diagram of the average promoter binding profiles of 5865 genes (clustered vertically). Dark blue indicates strong binding and white indicates no binding. The dendrogram at the top of the panel represents the hierarchical cluster analysis of the different binding profiles. (B,C) The overlap between significantly bound promoters of NC2α and NC2β (top panels), NC2 (NC2α or NC2β), TBP, and Mot1p (bottom panels) binding profiles are presented in Venn diagrams. Significantly bound promoters were selected in an ANOVA analysis with P-value of <0.01 and an enrichment of at least twofold (B) or P-value of <0.05 and a ratio of at least 1.5-fold (C). (D) Binding of TBP complexes to TATA-box-containing promoters. Promoters significantly bound (P < 0.05 and 1.5-fold enrichment) by the indicated factors were analyzed for occurrence of a canonical TATA-box. On the Y-axis the percentage of promoters containing a TATA-box is indicated for each binding profile. The dashed line indicates the overall percentage of TATA-box promoters in our data set. (E) Occurrence of TATA-box promoters within groups of promoters that were selected for relative high or low occupancy of the indicated TBP regulators. The ratios of NC2α, NC2β, Mot1p, Spt20p, or Taf1p over TBP were computed for significantly bound promoters. Subsequently, promoters were ranked and the occurrence of TATA-box-containing promoters was analyzed for the bottom 10% and top 10% of promoters. (F) Same as E except that the ratios were related to NC2β.

Next, we generated standard correlation plots for TBP, NC2, and Mot1p to analyze resemblance of binding profiles. As expected, there is a substantial degree of correlation between NC2α and NC2β binding (R = 0.67), NC2α and Mot1p (R = 0.61), and NC2β and Mot1p (R = 0.64) (Supplemental Fig. 3A–C). In contrast, the correlation between TBP and NC2α (R = 0.33), TBP and NC2β (R = 0.33), and TBP and Mot1p (R = 0.33) is more limited (Supplemental Fig. 3D–F). This is expected, as TBP is also present in TFIID and SAGA protein complexes and may bind to promoters independent of Taf1p. Thus, TBP binding represents the sum of the different protein complexes. To summarize, we find that NC2, TBP, and Mot1p colocalize on a large portion of promoters and that TFIID or SAGA bind to a subset of the NC2- and Mot1p-bound promoters.

NC2β has a preference for TATA-less promoters

Previous studies have shown that basal transcription factors can have different preferences for promoters depending on the presence of a canonical TATA-box (Lemaire et al. 2000; Geisberg et al. 2002). Global expression analysis indicated that TFIID is important for the maintenance of transcription from promoters lacking a canonical TATA-box, whereas SAGA is important for TATA-box-containing promoters (Basehoar et al. 2004). This prompted us to examine the TATA preference of the different factors included in this study. Among the TBP-, NC2α-, or NC2β-enriched promoters, ∼20% contains a TATA-box (Fig. 2D), which is comparable with the genome-wide distribution of TATA-boxes (Basehoar et al. 2004). In contrast, 27% of the Mot1p-bound promoters have a TATA-box, suggesting that Mot1p has a slight preference for TATA-box-containing promoters. Also, Spt20p preferentially binds to TATA promoters (31%), whereas Taf1p shows no enrichment of TATA promoters.

The analysis of Figure 2D only does not take in account whether promoter binding of a factor is strong or weak. To examine this in more detail, promoters were selected that have either strong or weak binding of Mot1p, NC2, TFIID, or SAGA and calculated the binding ratio of each factor relative to TBP binding. As expected, promoters that have a relatively strong binding of Mot1p and Spt20p display an increased preference for TATA promoters (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, in this analysis strong NC2α binding also correlates with a preference for TATA promoters. The fraction of TATA-containing promoters is reduced for genes that have a relatively high occupancy of NC2β and Taf1p. To examine the NC2β preference in more detail, relative occupancies of NC2α or Mot1p to NC2β were determined (Fig. 2F). This reveals that TATA promoters are underrepresented when the binding of NC2α and Mot1p is low relative to NC2β. This indicates that NC2β, but not NC2α, has a binding preference for promoters lacking a canonical TATA-box.

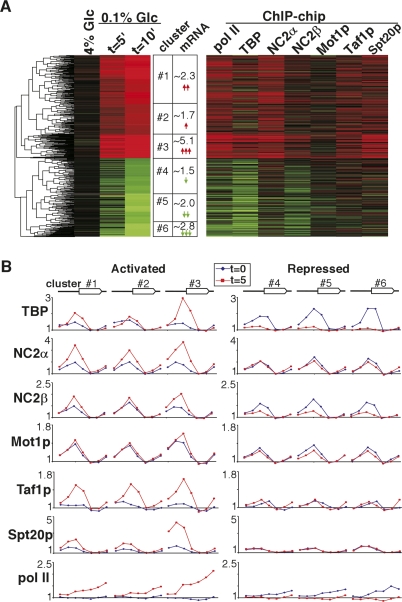

Differential binding of the NC2 subunits during transcriptional reprogramming

The presence of NC2 and Mot1p on the promoters of transcribed genes suggests that they are directly involved in transcription. Given that TFIID and SAGA are also present at these promoters, it is also possible that NC2 and Mot1p have a repressive function at active promoters. To examine interplay between activators and repressors more closely, we profiled the changes in binding patterns in response to changes in gene expression. To achieve this, mRNA expression profiles were determined in response to lowering glucose levels for 5 and 10 min (Fig. 3A, left panel). This analysis indicates that 522 genes are up-regulated (>1.5-fold) (Fig. 3A, colored red) and 400 genes are down-regulated (>−1.5-fold) (Fig. 3A, colored green) at 10 min after shifting from 4% to 0.1% glucose. ChIP samples from the different strains were prepared after the shift to low glucose in order to correlate changes in transcription factor binding with expression changes. Our previous analyses (van Oevelen et al. 2005) indicate that the primary changes in transcription factor binding occur already 5 min after the glucose shift. Figure 3A (right panel) displays the average binding changes to the promoter region or to the ORF for pol II after the glucose shift. Clustering analysis of the expression data resulted in three clusters of gene activation (∼2.3-, ∼1.7-, and ∼5.1-fold average increase in expression) and three clusters of gene repression (∼1.5-, ∼2.0-, and ∼2.8-fold average decrease in expression). The transcription activation and repression in these clusters strongly correlates to average pol II binding (Fig. 3B). For example, cluster 3 (activation ∼5.1-fold) displays the largest increase of pol II binding (from onefold to 2.5-fold), whereas cluster 2 (activation ∼1.7-fold) shows smallest increase in pol II binding. Changes in TBP binding also correlate well to transcription activation, with the largest increase of TBP binding in cluster 3. Strikingly, irrespective of the extent of repression, TBP is almost completely lost at all repressed genes. This suggests that there is a rapid reprogramming mechanism that actively removes TBP from promoters. Possibly, the different repression clusters originated from differences in pol II elongation rates and/or in mRNA half-lives. Interestingly, NC2α and NC2β are also recruited upon activation of transcription. In a similar analysis we find that Taf1p and Spt20p are recruited to activated promoters. This implies that there is a dynamic interplay between positive and negative regulators of TBP upon activation of transcription. At repressed genes, almost no loss of NC2α was detected, whereas NC2β binding is significantly reduced. Strikingly, Mot1p and Spt20p binding also do not change upon gene repression. This suggests that there are distinct roles of NC2α and NC2β during gene repression after shifting to low glucose.

Figure 3.

Reprogramming of pol II, TBP, NC2α, NC2β, Mot1p, Taf1p, and Spt20p binding during a shift from 4% to 0.1% glucose-containing medium. (A) Cluster diagram of genes that significantly changed in expression at 10 min after shifting cells from 4% to 0.1% glucose. Red indicates activated genes and green indicates repressed genes. Based on the gene expression we selected six top-level clusters that were used for subsequent analysis in B. The corresponding change in binding was measured at 5 min after the low glucose shift for TBP, NC2α, NC2β, Mot1p, Taf1p, and Spt20p at promoters and pol II in the ORF. Red indicates increased binding and green decreased binding. (B) Average binding of TBP, NC2α, NC2β, Mot1p, Taf1p, Spt20p, and pol II at t = 0 (blue line) and t = 5 min (red line) within the six clusters that are indicated in A.

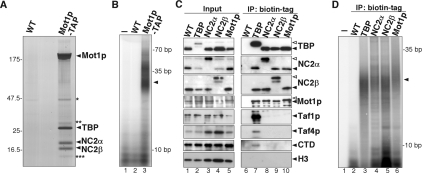

NC2, TBP, and Mot1p form a stable protein complex on DNA

The genomic binding profiles of Figure 2 indicated that TBP, NC2α, NC2β, and Mot1p bind to a similar set of promoters. To examine a physical association of these proteins on chromatin, we prepared extracts by micrococcal nuclease digestion of chromatin pellets. These extracts contained significant amounts of TBP, Mot1p, NC2, and TFIID (data not shown). Using a C-terminal TAP-tagged Mot1p strain we purified Mot1p from these chromatin extracts. Affinity-purified material was separated on a protein gel, and Coomassie-stained bands were analyzed by mass spectrometry (Fig. 4A). As expected, the band of ∼200 kDa corresponds to Mot1p. In addition, TBP was identified in the band that migrates at 27 kDa. Interestingly, the two smaller bands correspond to the NC2α and NC2β subunits. All four proteins were identified with high confidence scores. The association of TBP and NC2 with Mot1p was also confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Supplemental Fig. 4A). It has been shown that binding of NC2 to TBP depends on DNA. Therefore the presence of DNA in the affinity-purified Mot1p sample was investigated by T4 polynucleotide kinase labeling reactions. As expected, no signal was detected in the buffer only and wild-type control samples (Fig. 4B, lanes 1,2). A diffuse DNA pattern centered around 25 bp was detected in the Mot1p sample (Fig. 4B, lane 3). Quantification of the proteins and the DNA suggest that they are present in equimolar amounts (data not shown).

Figure 4.

TBP, NC2, and Mot1p copurify in chromatin extracts. (A) Chromatin extracts were isolated from C-terminal TAP-tagged Mot1p yeast cells and affinity-purified using a TAP-tag purification procedure. Eluates were separated on a SDS–polyacrylamide gradient gel, and Coomassie-stained bands were excised, subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion, and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The band labeled Mot1p was identified with 108 unique peptides with a 46% coverage. The labeled TBP, NC2α, and NC2β bands were identified with 17 (42% coverage), 19 (63% coverage), or 15 (54% coverage) unique peptides, respectively. The band labeled with one asterisk (*) is also present in the mock and represents Tef1p. The band labeled with two asterisks (**) mostly contained Mot1p and TBP derived peptides. In the band labeled with three asterisks (***), mostly NC2α peptides were found. (B) To determine the presence of DNA, part of the purification described in A was labeled in in a T4 polynucleotide kinase reaction using [γ-32P]ATP and loaded on a 20% polyacrylamide gel. The arrow indicates the position of the diffuse band. (C) Chromatin extracts were isolated from biotin-tagged TBP, NC2, or Mot1p strains expressing Escherichia coli BirA biotin ligase. Biotinylated proteins were immobilized using streptavidin beads. Input and eluates were analyzed by immublotting and probed for the indicated proteins. As a control, a nontagged strain expressing BirA was used. (D) To determine the presence of DNA, part of the samples described in C was eluted in TE buffer. Subsequently, samples were treated similarly to those described in B.

To confirm that NC2 interacts with the Mot1p–TBP protein complex, we purified TBP, NC2α, NC2β, and Mot1p individually from chromatin extracts using the biotin tag, and the bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblot. As expected, Mot1p copurifies with TBP (Fig. 4C, lane 7). In addition, NC2α, NC2β, and the TFIID subunits, Taf4p and Taf1p, are also present in the TBP purification. Small amounts of pol II can be detected by CTD antibodies, suggesting that this is partly a transcriptionally active form of TBP. The results are comparable when we purified TBP via the HA tag (Supplemental Fig. 4B). Mot1p, NC2, and TBP copurified with biotin-tagged NC2α or NC2β (Fig. 4C, lanes 8,9). Interestingly, pol II and TFIID subunits could not be detected. In line with these data, TBP, NC2α, and NC2β, but not pol II or TFIID, copurifies with biotin-tagged Mot1p (Fig. 4C, lane 10). Histone H3 was not detected in any of the samples (Fig. 4C, lanes 6–10). Analysis of a nontagged control strain further confirmed that the detected signals are specific (Fig. 4C, lane 6). DNA labeling of these samples results in a comparable DNA pattern as for affinity-purified Mot1p (Fig. 4D, lanes 3–6). Dnase I treatment after the labeling reaction eliminates this pattern, verifying the presence of DNA (Supplemental Fig. 4C). These data show that NC2, TBP, and Mot1p can form a complex on DNA in vivo.

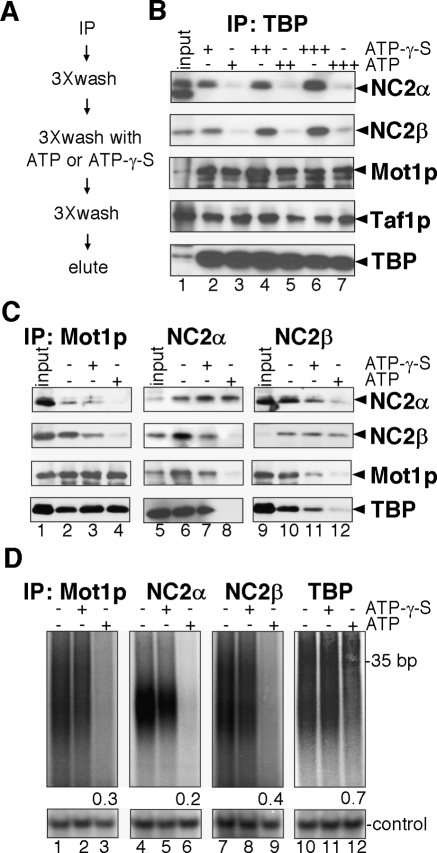

ATP dependent dissociation of NC2 from TBP and Mot1p

An important function of Mot1p is its ability to remove TBP from DNA (Auble et al. 1994). For this action Mot1p uses its intrinsic (d)ATPase activity. To test whether ATP hydrolysis disrupts the TBP, NC2, and Mot1p interactions, the TBP–Mot1p–NC2–DNA complex was purified from chromatin extracts and incubated with ATP or a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog (ATP-γ-S) (Fig. 5A). Upon ATP treatment, Taf1p and Mot1p association with TBP remained unchanged (Fig. 5B, lanes 2–7), whereas binding of NC2α and NC2β is strongly decreased (Fig. 5B, lanes 3,5,7). In agreement with this, binding of NC2α and NC2β, but not of TBP, is reduced after ATP addition in samples purified via tagged Mot1p (Fig. 5C, lane 4). Conversely, an ATP dependent reduction in Mot1p and TBP is observed when the complex was purified via NC2α or NC2β. Interestingly, ATP addition results in partial disruption of the NC2 heterodimer (Fig. 5C, lanes 5–12). Part of each sample was processed for DNA analysis. Addition of ATP to the Mot1p-, NC2α-, and NC2β-purified complexes results in a loss of >60% of the DNA (Fig. 5D, lanes 1–9). In contrast, the amount of DNA in the TBP sample is only reduced by 30% (Fig. 5D, lanes 10–12). This is expected, as this DNA also represents TFIID–DNA or TBP–DNA complexes, which would be resistant to ATP treatment (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that Mot1p is involved in active disruption of NC2-TBP-DNA interactions, and perhaps can also dissociate the NC2α and NC2β heterodimer.

Figure 5.

The TBP–NC2–Mot1p–DNA complex is disrupted upon treatment with ATP. (A) Experimental scheme. (B) TBP–NC2–Mot1p was isolated via TBP and treated as described in A with 1 μM (lanes 2,3), 10 μM (lanes 4,5), and 100 μM (lanes 6,7) of ATP or ATP-γ-S as indicated. (C) TBP-NC2-Mot1p was isolated via Mot1p (lanes 1–4), NC2α (lanes 5–8), and NC2β (lanes 9–12). Samples were assayed as described in A, and were either untreated (lanes 2,6,10), treated with 10 μM ATP-γ-S (lanes 3,7,11), or ATP (lanes 4,8,12). (D) To determine the presence of DNA, samples were treated like B and C except that 1 μM of ATP or ATP-γ-S was used, and samples were eluted in TE buffer. Subsequently, samples were radioactively labeled in a T4 polynucleotide kinase reaction using [γ -32P]ATP and analyzed on a 20% polyacrylamide gel. To control for equal labeling efficiency a single-stranded 19-mer oligo was included in each labeling reaction. The samples were quantified and corrected for the 19-mer control oligo and nontreated sample. The relative quantification of DNA levels for each sample is indicated.

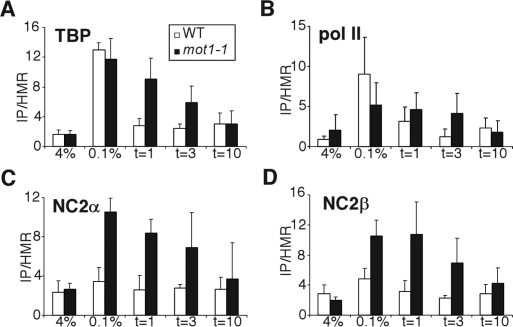

TBP and NC2 dissociation kinetics are delayed in mot1-1 mutant

In line with our in vitro data, it has been found that promoter binding of NC2 is increased in a mot1-1 mutant strain (Geisberg et al. 2002). We decided to examine the role of NC2 and Mot1p in TBP dissociation during transcriptional shut-off in vivo. This was tested by analyzing their binding to the HXT2 promoter. HXT2 encodes a high-affinity hexose transporter, whose expression is highly responsive to changes in glucose concentration (Ozcan and Johnston 1995). HXT2 expression was first induced by shifting the yeast cells from 4% to 0.1% glucose. Next, glucose was added back to 4% to repress the gene, and samples were taken after 1, 3, or 10 min. To reduce variation between samples, we carried out the ChIPs from a single chromatin extract using antibodies against TBP, NC2α, NC2β, and pol II. A primer set corresponding to the core promoter region of HXT2 (−170/−76) was used, and the signals were normalized to a fragment of the silent HMR locus. In wild-type cells TBP dissociation from the HXT2 promoter is complete in less than 1 min (Fig. 6A). In contrast, TBP binding in the mot1-1 mutant is reduced to 50% only after 3 min. Similarly, dissociation of pol II is delayed (Fig. 6B). Upon HXT2 transcription activation, binding of NC2α and NC2β is increased in mot1-1 mutant compared with wild type. In the mot1-1 mutant, TBP and the NC2 subunits display a comparable delay in dissociation (Fig. 6C,D). Since the ChIP signals of NC2α and NC2β in wild-type cells were difficult to detect, we used biotin-tagged NC2α and NC2β to determine the dissociation rate in wild-type cells. In line with the results obtained for TBP, most of NC2α and NC2β are lost after 3 min (Supplemental Fig. 5A,B). In conclusion, TBP and NC2 display a delayed dissociation rate in the mot1-1 mutant. These in vivo data are in agreement with the in vitro results of Figure 5 showing that Mot1p can disrupt a TBP-NC2-DNA complex. Taken together, our study indicates that NC2 and Mot1p cooperate to restrict the transcription of active genes.

Figure 6.

The kinetics of TBP, NC2, and pol II dissociation during transcriptional repression of the HXT2 gene. Wild-type or mot1-1 mutant cells grown in 4% glucose-containing medium were shifted to 0.1% glucose for 5 min. Subsequently, glucose was added back to 4% and samples were taken after 1, 3, and 10 min. Using different antibodies, the binding of TBP (A), pol II (B), NC2α (C), and NC2β (D) in wild-type and mot1-1 mutant yeast strains were analyzed. A primerset (−170/−76) corresponding to the core promoter of HXT2 was used for quantification of isolated DNA. A fragment of the HMR locus was used as a nonbinding control.

Discussion

Here we present a detailed map of the genome wide localization of TBP, NC2, Mot1p, SAGA, TFIID, and pol II for yeast cells grown in exponential phase and during a shift from high to low glucose. We isolated and characterized a Mot1p–NC2–TBP–DNA complex from chromatin extracts, which dissociates into Mot1p–TBP, NC2 subunits, and DNA, depending on ATP hydrolysis. This is consistent with the observation that NC2 binding is increased in mot1 loss-of-function mutants (Geisberg et al. 2002). Together, our observations indicate that NC2 and Mot1p coordinately act to regulate the output of active promoters in yeast. These findings have important ramifications for the dynamic interplay between negative (NC2 and Mot1p) and positive regulators (TFIID and SAGA) of TBP function in transcription initiation.

Our findings are consistent with a model in which Mot1p and NC2 cooperate to restrict TBP activity stimulated by TFIID and SAGA, thereby limiting the transcriptional output of active genes. On promoters of active genes ATP hydrolysis by Mot1p would act to dissociate the transcriptionally inert Mot1p–NC2–TBP complex from the promoter to allow association of TFIID or free TBP, which would direct productive preinitiation complex assembly and subsequent transcription (Fig. 7). This dynamic exchange model is supported by the following observations. First, the genomic binding profiles of Mot1p, NC2, and TBP are largely overlapping (Fig. 2A,B). Second, NC2 and Mot1p binding positively correlates with promoter activity (Fig. 1F–H). Third, SAGA and TFIID association to promoters overlaps with NC2 and Mot1p binding (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. 2C,D). Fourth, both NC2 and TFIID association is increased upon activation of promoters (Fig. 3A). And, lastly, consistent with sequential ChIP experiments (Geisberg and Struhl 2004) no TFIID, pol II (Fig. 4C), or TFIIB (data not shown) could be detected in the Mot1p–NC2–TBP–DNA complexes isolated from chromatin, indicating that this represents a transcriptionally inactive complex.

Figure 7.

Model for the interplay between TBP–NC2–Mot1p and TFIID or free TBP. On an active promoter the Mot1p–NC2–TBP complex turns over to allow TFIID or free TBP association to direct productive preinitiation complex assembly and transcription.

An attractive feature of this dynamic exchange model is that on active promoters TBP can be kept in a equilibrium of active (TFIID or free TBP) and inactive (NC2–Mot1p) forms. Altering the activities of the TBP regulatory complexes would allow a very rapid adjustment of the transcriptional response. Indeed, cellular stress conditions have been shown to alter the properties of Mot1p–TBP complexes (Geisberg and Struhl 2004). The dynamic exchange model is also consistent with observations that transcription in eukaryotic cells occurs in a discontinuous manner with intermittent pulses of transcription. The pulses are irregular in length and spacing and they are referred to as transcriptional bursts (Chubb et al. 2006; Raj et al. 2006). During these bursts TFIID or free TBP would be occupying the promoter directing transcription, while between bursts the promoter would be occupied by the inactive Mot1p-NC2-TBP complex. Interestingly, the sequence of the TATA-box has been found to determine variability of transcriptional bursts (Blake et al. 2006).

NC2 and Mot1p reside on active genes

Our results extend earlier proposals of NC2 and Mot1p as transcriptional repressors (for review, see Pugh 2000). A substantial amount of yeast genetic data have been accumulating, which supports a repressive function for the Mot1p and NC2 complexes (e.g., Davis et al. 1992; Prelich 1997; Lee et al. 1998; Peiro-Chova and Estruch 2007). The first indications for positive functions for Mot1p and NC2 came from in vitro transcription experiments showing that under certain conditions addition of these proteins stimulates transcription (Muldrow et al. 1999; Willy et al. 2000). mRNA expression profiling studies of Mot1p and NC2 mutant strains also indicated positive functions for these complexes (Andrau et al. 2002; Cang and Prelich 2002; Dasgupta et al. 2002; Geisberg et al. 2002). These were supported by ChIP studies on selected genes, which indicated that Mot1p and NC2 are recruited to promoters upon gene activation (Geisberg et al. 2001, 2002; Andrau et al. 2002; Dasgupta et al. 2002; Geisberg and Struhl 2004; Zanton and Pugh 2004). Our study now expands this analysis to the entire genome, showing that binding of Mot1p and both NC2 subunits positively correlates with gene activity rather than with gene repression. Our localization results for yeast NC2 are supported by a recent study of human cells, which indicated that human NC2α is also localized to a large number of active promoters (Albert et al. 2007). The overlapping profiles of NC2 and Mot1p with TBP support the view that NC2 and Mot1p require TBP for association to pol II promoters (Geisberg et al. 2002). It is interesting to note that promoters with a high ratio of NC2 and Mot1p to TBP are also enriched for TFIID and SAGA (data not shown). Surprisingly, these genes are expressed at a lower level, which suggests that this set of genes is highly regulated. In line with this, we found that many of these promoters have a high histone turnover rate (Dion et al. 2007; data not shown).

By analyzing a selected set of promoters it was found that the DNA surrounding the TATA-box plays an important role for Mot1p function, as the TATA-less promoters of HIS3 and HIS4 are more dependent on Mot1p than the canonical TATA promoters (Collart 1996; Geisberg et al. 2002). In contrast, microarray mRNA expression analysis indicated that Mot1p functions to repress TATA promoters (Basehoar et al. 2004). In the Mot1p binding profile we find a modest enrichment for TATA promoters (Fig. 2D). This does not correspond to the relaxed specificity of Mot1p–TBP and human BTAF1–TBP complex (Gumbs et al. 2003; Klejman et al. 2005). Similar to Mot1p, SAGA-enriched promoters display a slightly higher proportion of TATA-boxes (Fig. 2D), which is consistent with the observation that TATA-box promoters preferentially use SAGA (Basehoar et al. 2004). Together, this supports previous models that Mot1p and SAGA collaborate in regulating gene expression (Collart 1996; Madison and Winston 1997; van Oevelen et al. 2005).

Differential roles of the NC2 subunits

The genomic localization profiles of NC2α and NC2β are largely overlapping during normal growth, which indicates that these proteins work as a complex. Previous ChIP analyses indicated that, upon diauxic shift, the two subunits may play different functions. A relative enrichment of NC2α was observed on activated promoters, and NC2β was more abundant on repressed promoters (Creton et al. 2002). In contrast, we find that, upon glucose-induced transcriptional reprogramming, both NC2α and NC2β are recruited to activated promoters. Fifty percent of these activated promoters bear a canonical TATA-box. The extent of NC2β recruitment to the activated promoters seems less compared with NC2α (Fig. 3B), and NC2β is slightly underrepresented on TATA promoters (Fig. 2E,F). Previous analyses showed that transcription from the TATA-less promoter of HIS3 requires functional NC2α and NC2β (Lemaire et al. 2000). Clearly, more experiments are needed to elucidate the selective functions of NC2α and NC2β.

It is interesting to note that ChIP–reChIP experiments showed that Mot1p and TFIIB can co-occupy activated promoters during heat shock (Geisberg and Struhl 2004). Structural analysis of the human TBP–NC2 complex indicates that NC2β and TFIIB binding are mutually exclusive (Kamada et al. 2001). And a mutational study of human TBP indicated that the BTAF1 and TFIIB interact with different residues of human TBP (Klejman et al. 2005). Possibly, selective NC2β dissociation from the NC2–Mot1p–TBP–promoter complex induced by heat shock allows TFIIB entry to direct productive transcription. It is possible that the relative differences in NC2 subunit association during promoter activation, e.g., induced by low glucose shift or heat shock, represent transient effects. As they are most prevalent during transcriptional reprogramming, this suggests regulation of Mot1p-mediated dissociation of NC2–Mot1p–TBP–promoter complexes.

Concluding remarks

Our genomic localization study now provides an explanation for the seemingly contradictory results for NC2 and Mot1p obtained from biochemical and mRNA profiling experiments. Whereas previous models indicated that Mot1p and NC2 compete for binding to TBP-DNA complexes (Geisberg et al. 2002), we now propose that Mot1p and NC2 cooperate in a dynamic manner to restrict TBP activity stimulated by SAGA and TFIID to limit transcription levels. This dynamic exchange model provides a framework for further experiments regarding the interplay of TBP regulatory proteins.

Materials and methods

Strains and plasmids

NC2α and NC2β were tagged with the biotin-acceptor-sequence (avitag) at the N terminus and Mot1p, Spt20p, and Taf1p at the C terminus in wild-type W303B (MATα ade2-1 ura3-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 can1-100) as described previously (van Werven and Timmers 2006). Strains used in this study are described in Supplemental Table 1. In order to achieve biotinylation of the avitag, strains were transformed with pRS313-BirA-NLS plasmid expressing Escherichia coli BirA biotin ligase.

ChIP

ChIP has been carried out as described previously (van Werven and Timmers 2006). In short, 400 mL of mid-log growing yeast cells (OD600 = 0.4) were cross-linked with 1% formadehyde for 20 min at room temperature, the reaction was quenched with glycine, and cells were collected by centrifugation. Subsequently, cells were disrupted using a beadbeater and sonicated (Bioruptor, Diagenode: seven cycles, 30 sec on/off, medium setting) to produce an average DNA fragment size of 400 bp. For the biotinylation tag ChIPs, 500 μL of extract were incubated with 80 μL of Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin (Invitrogen) for 1 h and 45 min. Samples were subsequently washed three times with 0.5 M LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% Na-deoxycholate and three times with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 3% SDS. For the antibody ChIPs in Figure 6, 2.5 μL of antibodies (CTD, TBP, NC2α, and NC2β) were coupled to 30 μL Protein A Dynabeads (Invitrogen). After incubation with 500 μL of extract the antibody ChIPs were washed three times in FA lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES KOH at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) and three times with FA lysis buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl. Cross-links of the ChIP samples was reversed overnight at 65°C in 150 μL 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS. Samples were treated with proteinase K, and DNA was recovered for further analysis.

Microarray expression profiling

W303B wild-type strain was grown in synthetic complete (SC) medium containing 4% glucose till OD600 = 0.4. For the low glucose shift, cells were collected by centrifugation and suspended in SC containing 0.1% glucose. Samples were taken after 5 and 10 min. Total RNA was isolated as described (van Oevelen et al. 2005). Samples were subsequently amplified using the T7 amplification method, labeled with Cy3 or Cy5 dyes, and hybridized to yeast oligo microarray arrays. Each time point was grown, amplified, and hybridized in quadruplicate against a common reference pool. Slides were scanned and normalized, and P-values were computed as described (van de Peppel et al. 2005). Probes with P < 0.05 value and average 1.5-fold change were considered as significantly changed. For the clustering analysis Genespring 7.0 (Agilent) was used.

ChIP–chip amplification, labeling, and hybridization

Samples were amplified using a double round T7 based amplification procedure as described previously (van Bakel et al. 2008). In short, in a terminal transferase reaction a poly-dT was generated at the 3′ end of the DNA. In a klenow fill reaction the poly-dT was used as a template for the T7-(dA)18 oligo. Next, samples were amplified using MEGAscript T7 kit (Ambion). After the first round, samples were reverse transcribed using random primers followed by a Klenow fill in reaction using T7-(dA)18 oligo. Similar to the first round, samples were amplified using MEGAscript T7 kit (Ambion) except that 3-aminoallyl-UTP was used in the reaction. Amplified samples were labeled using monofunctional NHS-ester Cy3 or Cy5 dye (GE Healthcare) and hybridized to oligonucleotide arrays (Agilent Technologies) that contain 60-mer oligonucleotide probes covering the complete yeast genome at an average of 266-bp resolution. The slides were washed and scanned accordingly. Genome-wide localization analysis data were generated from two biological samples that were differentially labeled (Cy3 or Cy5) and hybridized independently.

ChIP–chip data analysis

Following quantification, the microarray data was normalized using a density lowess-normalization algorithm (for detailed description see the Supplemental Material). The binding enrichment was computed by dividing the normalized chip signal over the input signal. With use of MAANOVA statistical package, P-values were determined by a permutation F2 test in which residuals were shuffled 1000 times. A combination of P-values and binding ratio cutoffs was used to identify significantly bound genomic regions. Average binding analysis was carried out as described by van Bakel et al. (2008).

Preparation of chromatin extracts

Chromatin extracts were prepared essentially as described (Vermeulen et al. 2007). Briefly, cells were disrupted using glass beads in nucleosome isolation buffer (NIB) 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES NaOH (pH 7.8), 250 mM sucrose. The pellet was collected by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. This pellet was washed and resuspended in NIB plus 2 mM CaCl2. Next, samples were treated with 8 units of micrococcal nuclease per 1 mL extract (Sigma) for 2 min at 30°C. The reaction was stopped with 10 mM EGTA (pH 8.0). The NaCl concentration of each sample was adjusted to 150 mM before samples were centrifugated at 14,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant represents the chromatin extract. In these extracts nucleosomal particles are the most abundant protein–DNA complex, as evidenced by the prominence of nucleosomal-sized DNA of ∼150 bp.

Immunoprecipitation

One liter of cultured yeast cells (OD600 = 0.7) was collected by centrifugation from which a chromatin extract was prepared. For the immunoprecipitation 1 mL of chromatin extracts were incubated with 20 μL of Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin (Invitrogen) or 20 μg anti-HA (12CA5) antibodies coupled to 20 μL Protein A Dynabeads (Invitrogen) for 2 h at 4°C. Samples were then washed six times with NIB buffer plus 150 mM NaCl and eluted by incubating for 5 min at 95°C in sample buffer for immunoblot analysis or 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA for labeling of DNA.

Radioactive DNA labeling

DNA isolated during the immunoprecipitation experiments was treated with 1 μL of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP) (Roche) for 1 h at 37°C followed by inactivation of the enzyme at 65°C for 20 min. Samples were radioactively labeled in a reaction containing kinase buffer, 5 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs), and 25 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min at 37°C. The labeled material was treated with 0.5 μL RNase (10 mg/mL) and analyzed on a 20% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was dried and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen for analysis and quantification with a Storm 820 scanner (Molecular Dynamics) using ImageQuant TL software.

TAP purification

One liter of wild-type or Mot1-TAP-tagged cells were grown in YPD till OD600 = 3 and were collected by centrifugation. Approximately 12 mL of chromatin extract was prepared from these cell pellets. The chromatin extracts were incubated with 200μL IgG sepharose fast flow column (Pharmacia) for 2 h at 4°C on a rotating platform. The samples were subsequently treated according to a standard TAP tag procedure as described (Rigaut et al. 1999). Purified proteins were concentrated as described (Wessel and Flugge 1984).

Protein identification by mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry analysis was performed as described previously (Mousson et al. 2007). Selected bands from the SDS/PAGE gel were digested using sequencing grade trypsin (Roche) and analyzed using LTQ-FTICR (Thermo Fisher Scientific) mass spectrometry. LTQ-FTICR data were searched, using an in-house-licensed mascot (Matrix Science) search engine, against the Yeast SGD database with carbamidomethyl cysteine as a fixed modification and oxidized methionines as variable modification. The mass tolerance of the precursor ion was set to 3 ppm and that of fragment ions to 0.6 Da. Scaffold (Proteome Software) was used to validate protein identifications. Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at >99.9% probability and contained at least two identified peptides. For detailed description of the method see Supplemental Material.

Accession numbers

The raw and normalized ChIP–chip and microarray expression data have been submitted to the public microarray ArrayExpress database with accession numbers E-MTAB-21 and E-MTAB-22, respectively. Mass spectrometry protein data have been submitted to the proteomics identifications database (PRIDE) with accession numbers 3355–3368.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M.A. Collart and P.A. Weil for generously providing antibodies and K. Struhl for providing yeast strains. We are grateful to D. van Leenen and D. Bouwmeester from the UMC Utrecht/Utrecht University microarray facility for technical assistance. We thank G. Spedale and W.W.M. Pijnappel for advice on the TAP tag purification method. We also gratefully acknowledge our laboratory members for discussions and F. Mousson, W.W.M. Pijnappel, and P. de Graaf for critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by grants (805.47.080 and 825.06.033) of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), the Netherlands Proteomics Centre (NPC), and the European Union (LSHG-CT-2006-037445).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1682308.

References

- Albert T.K., Grote K., Boeing S., Stelzer G., Schepers A., Meisterernst M. Global distribution of negative cofactor 2 subunit-α on human promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:10000–10005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703490104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrau J.C., Van Oevelen C.J., Van Teeffelen H.A., Weil P.A., Holstege F.C., Timmers H.T. Mot1p is essential for TBP recruitment to selected promoters during in vivo gene activation. EMBO J. 2002;21:5173–5183. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auble D.T., Hansen K.E., Mueller C.G., Lane W.S., Thorner J., Hahn S. Mot1, a global repressor of RNA polymerase II transcription, inhibits TBP binding to DNA by an ATP-dependent mechanism. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:1920–1934. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basehoar A.D., Zanton S.J., Pugh B.F. Identification and distinct regulation of yeast TATA box-containing genes. Cell. 2004;116:699–709. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake W.J., Balazsi G., Kohanski M.A., Isaacs F.J., Murphy K.F., Kuang Y., Cantor C.R., Walt D.R., Collins J.J. Phenotypic consequences of promoter-mediated transcriptional noise. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cang Y., Prelich G. Direct stimulation of transcription by negative cofactor 2 (NC2) through TATA-binding protein (TBP) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:12727–12732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202236699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb J.R., Trcek T., Shenoy S.M., Singer R.H. Transcriptional pulsing of a developmental gene. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart M.A. The NOT, SPT3, and MOT1 genes functionally interact to regulate transcription at core promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6668–6676. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creton S., Svejstrup J.Q., Collart M.A. The NC2 α and β subunits play different roles in vivo. Genes & Dev. 2002;16:3265–3276. doi: 10.1101/gad.234002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J.A., Grant P.A. Multi-tasking on chromatin with the SAGA coactivator complexes. Mutat. Res. 2007;618:135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta A., Darst R.P., Martin K.J., Afshari C.A., Auble D.T. Mot1 activates and represses transcription by direct, ATPase-dependent mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:2666–2671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052397899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J.L., Kunisawa R., Thorner J. A presumptive helicase (MOT1 gene product) affects gene expression and is required for viability in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:1879–1892. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion M.F., Kaplan T., Kim M., Buratowski S., Friedman N., Rando O.J. Dynamics of replication-independent histone turnover in budding yeast. Science. 2007;315:1405–1408. doi: 10.1126/science.1134053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisberg J.V., Struhl K. Cellular stress alters the transcriptional properties of promoter-bound Mot1–TBP complexes. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:479–489. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisberg J.V., Holstege F.C., Young R.A., Struhl K. Yeast NC2 associates with the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex and selectively affects transcription in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:2736–2742. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2736-2742.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisberg J.V., Moqtaderi Z., Kuras L., Struhl K. Mot1 associates with transcriptionally active promoters and inhibits association of NC2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:8122–8134. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.23.8122-8134.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goppelt A., Stelzer G., Lottspeich F., Meisterernst M. A mechanism for repression of class II gene transcription through specific binding of NC2 to TBP-promoter complexes via heterodimeric histone fold domains. EMBO J. 1996;15:3105–3116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.A., Schieltz D., Pray-Grant M.G., Steger D.J., Reese J.C., Yates J.R., Workman J.L. A subset of TAF(II)s are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell. 1998;94:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbs O.H., Campbell A.M., Weil P.A. High-affinity DNA binding by a Mot1p-TBP complex: Implications for TAF-independent transcription. EMBO J. 2003;22:3131–3141. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege F.C., Jennings E.G., Wyrick J.J., Lee T.I., Hengartner C.J., Green M.R., Golub T.R., Lander E.S., Young R.A. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell. 1998;95:717–728. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inostroza J.A., Mermelstein F.H., Ha I., Lane W.S., Reinberg D. Dr1, a TATA-binding protein-associated phosphoprotein and inhibitor of class II gene transcription. Cell. 1992;70:477–489. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada K., Shu F., Chen H., Malik S., Stelzer G., Roeder R.G., Meisterernst M., Burley S.K. Crystal structure of negative cofactor 2 recognizing the TBP–DNA transcription complex. Cell. 2001;106:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klejman M.P., Zhao X., van Schaik F.M., Herr W., Timmers H.T. Mutational analysis of BTAF1–TBP interaction: BTAF1 can rescue DNA-binding defective TBP mutants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5426–5436. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuras L., Kosa P., Mencia M., Struhl K. TAF-containing and TAF-independent forms of transcriptionally active TBP in vivo. Science. 2000;288:1244–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.I., Wyrick J.J., Koh S.S., Jennings E.G., Gadbois E.L., Young R.A. Interplay of positive and negative regulators in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:4455–4462. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.I., Causton H.C., Holstege F.C., Shen W.C., Hannett N., Jennings E.G., Winston F., Green M.R., Young R.A. Redundant roles for the TFIID and SAGA complexes in global transcription. Nature. 2000;405:701–704. doi: 10.1038/35015104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire M., Xie J., Meisterernst M., Collart M.A. The NC2 repressor is dispensable in yeast mutated for the Sin4p component of the holoenzyme and plays roles similar to Mot1p in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;36:163–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.Y., Bhaumik S.R., Green M.R. Distinct classes of yeast promoters revealed by differential TAF recruitment. Science. 2000;288:1242–1244. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison J.M., Winston F. Evidence that Spt3 functionally interacts with Mot1, TFIIA, and TATA-binding protein to confer promoter-specific transcriptional control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:287–295. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson P., Leimgruber E., Creton S., Collart M.A. The dual control of TFIIB recruitment by NC2 is gene specific. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:539–549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisterernst M., Roy A.L., Lieu H.M., Roeder R.G. Activation of class II gene transcription by regulatory factors is potentiated by a novel activity. Cell. 1991;66:981–993. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90443-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousson F., Kolkman A., Pijnappel W.W., Timmers H.T., Heck A.J. Quantitative proteomics reveals regulation of dynamic components within TATA-binding protein (TBP) transcription complexes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;7:845–852. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700306-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldrow T.A., Campbell A.M., Weil P.A., Auble D.T. MOT1 can activate basal transcription in vitro by regulating the distribution of TATA binding protein between promoter and nonpromoter sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:2835–2845. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan S., Johnston M. Three different regulatory mechanisms enable yeast hexose transporter (HXT) genes to be induced by different levels of glucose. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:1564–1572. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiro-Chova L., Estruch F. Specific defects in different transcription complexes compensate for the requirement of the negative cofactor 2 repressor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2007;176:125–138. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.066829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokholok D.K., Harbison C.T., Levine S., Cole M., Hannett N.M., Lee T.I., Bell G.W., Walker K., Rolfe P.A., Herbolsheimer E., et al. Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast. Cell. 2005;122:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon D., Campbell A.M., Bai Y., Weil P.A. Yeast Taf170 is encoded by MOT1 and exists in a TATA box-binding protein (TBP)–TBP-associated factor complex distinct from transcription factor IID. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:23135–23140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelich G. Saccharomyces cerevisiae BUR6 encodes a DRAP1/NC2α homolog that has both positive and negative roles in transcription in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:2057–2065. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelich G., Winston F. Mutations that suppress the deletion of an upstream activating sequence in yeast: Involvement of a protein kinase and histone H3 in repressing transcription in vivo. Genetics. 1993;135:665–676. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh B.F. Control of gene expression through regulation of the TATA-binding protein. Gene. 2000;255:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A., Peskin C.S., Tranchina D., Vargas D.Y., Tyagi S. Stochastic mRNA synthesis in mammalian cells. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaut G., Shevchenko A., Rutz B., Wilm M., Mann M., Seraphin B. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999;17:1030–1032. doi: 10.1038/13732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S.L., Weil P.A. Identification of two novel TAF subunits of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae TFIID complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:13895–13900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluesche P., Stelzer G., Piaia E., Lamb D.C., Meisterernst M. NC2 mobilizes TBP on core promoter TATA boxes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:1196–1201. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers H.T., Tora L. SAGA unveiled. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bakel H., van Werven F.J., Radonjic M., Brok M.O., van Leenen D., Holstege F.C., Timmers H.T. Improved genome-wide localization by ChIP–chip using double-round T7 RNA polymerase-based amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Peppel J., Kettelarij N., van Bakel H., Kockelkorn T.T., van Leenen D., Holstege F.C. Mediator expression profiling epistasis reveals a signal transduction pathway with antagonistic submodules and highly specific downstream targets. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oevelen C.J., van Teeffelen H.A., Timmers H.T. Differential requirement of SAGA subunits for Mot1p and Taf1p recruitment in gene activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:4863–4872. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.4863-4872.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Werven F.J., Timmers H.T. The use of biotin tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae improves the sensitivity of chromatin immunoprecipitation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen M., Mulder K.W., Denissov S., Pijnappel W.W., van Schaik F.M., Varier R.A., Baltissen M.P., Stunnenberg H.G., Mann M., Timmers H.T. Selective anchoring of TFIID to nucleosomes by trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4. Cell. 2007;131:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Jones G.M., Prelich G. Genetic analysis connects SLX5 and SLX8 to the SUMO pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2006;172:1499–1509. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.052811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel D., Flugge U.I. A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal. Biochem. 1984;138:141–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willy P.J., Kobayashi R., Kadonaga J.T. A basal transcription factor that activates or represses transcription. Science. 2000;290:982–985. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanton S.J., Pugh B.F. Changes in genomewide occupancy of core transcriptional regulators during heat stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:16843–16848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404988101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]