Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is recognized as a leading cause of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal failure. Chronic renal failure is associated with insulin resistance and, in advanced renal failure, decreased insulin degradation. Both of these abnormalities are partially reversed with the institution of dialysis. Except for diet with protein restriction, patients with diabetes should be preferably treated with insulin. The management of the patients with hyperglycemia and chronic renal failure calls for close collaboration between the diabetologist and the nephrologists. This collaboration is very important so that the patient will not be confused and will not lose confidence to the doctors. Furthermore good glycemic control in these patients seems to reduce microvascular and macrovascular complications.

Keywords: hyperglycemia therapy, diabetes, chronic kidney disease

Diabetes mellitus is a major health problem of increasing magnitude worldwide with a great impact on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality1. Moreover diabetes mellitus is recognized as a leading cause of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States and in Western Countries2. Large epidemiological studies have shown that one third of the patients on hemodialysis or renal transplant recipients are diabetics, predominantly with type 2 diabetes3. Moreover well designed randomized studies have provided convincing evidence on the value of glycemic control in preventing both micro and macrovascular disease4. The UK Prospective Diabetes Study have shown that intensive treatment of patients with newly diagnosed diabetes reduced the risk for myocardial infarction by 16%, amputation or death from peripheral vascular disease by 35%,fatal myocardial infarction by 6%, nonfatal myocardial infarction by 21%, fatal sudden death by 45% and amputation by 39%. Every 1% reduction in glycosylated hemoglobin was associated with reductions in risk of 21% for any end point related to diabetes 21% for diabetes related deaths, 14% for myocardial infarction and 37% for microvascular complications. Therefore the glycemic control is very important for the prevention of diabetic complications5, 6.

The problem of diabetic nephropathy

In the past is has been believed that fewer patient with type 2 diabetes developed nephropathy and that proteinuria in these patients had relatively better prognosis compared to patients with type 1 diabetes. Well designed prospective studies have shown that once proteinuria develops the risk of end-stage renal disease is similar in both types of diabetes7. Moreover recent epidemiologic data have shown that end-stage renal failure has increased dramatically in patients with type 2 diabetes The reason for this is that the treatment of hypertension and coronary heart disease have improved life expectancy of the patients with type 2 diabetes and larger proportion of them will develop nephropathy and end-stage renal disease8,9.

The role of kidney in the metabolism of insulin in normal man and in renal failure

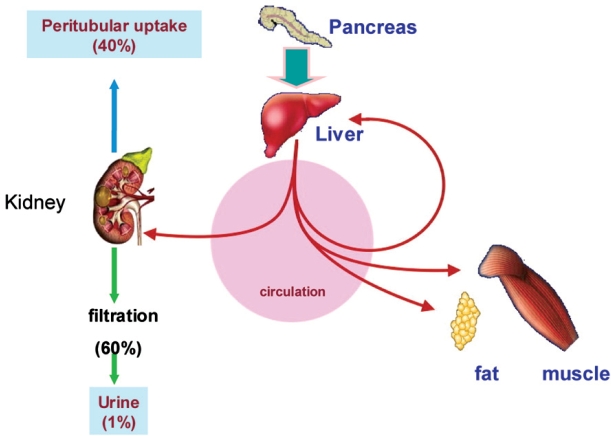

In non-diabetic individual, 40-50% of insulin secreted by pancreas is extracted during its first passage through the liver10,11. Consequently, the kidney plays a smaller role in disposing of insulin secreted in non-diabetic individual than in disposing of insulin injected into diabetic patients (Figure 1). Endogenously secreted insulin is degraded by liver, exogenous insulin is primarily eliminated by the kidney.

Figure 1. Metabolism of insulin. Insulin is freered at the glomerulus and then extensively reabsorbed by the proximal tubule. Of the total renal insulin clearance, approximately 60% occurs by glomerular filtration and 40% by extraction from peritubular vessels. (Adapted from Rabkin R et al. The renal metabolism of insulin. Diabetoligia 1984; 27: 351-357).

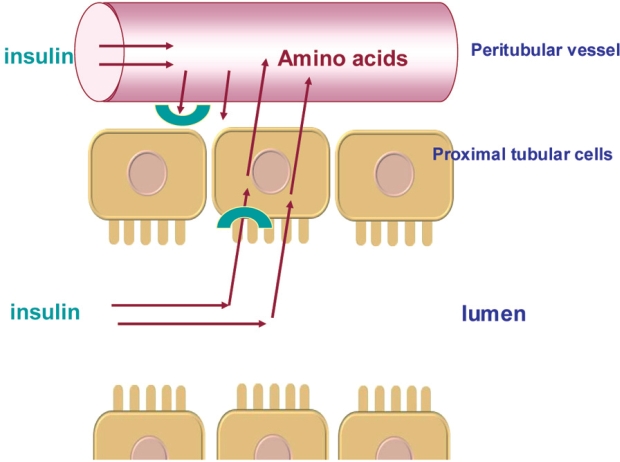

The kidneys play an important role in the clearance of insulin from the systemic circulation. Insulin has a molecular weight of 5734 and is therefore freely filtered at the glomerulus and then extensively reabsorbed by the proximal tubule. Of the total renal insulin clearance, approximately 60% occurs by glomerular filtration and 40% by extraction from peritubular vessels. Insulin in the tubular lumen enters the proximal tubular cell by carrier-mediated endocytosis and is then transported into lysosomes where it is metabolized into amino acids that are released into peritubular vessels by diffusion. In addition to luminal clearance via glomerulal filtration, the kidneys clear insulin from the post-glomerular peritubular circulation (Figure 2). These intrarenal pathways of insulin removal involve both receptor and non-receptor mediated uptake. The net effect is that less than 1% of filtered insulin appears in final urine12–14.

Figure 2. Intrarenal pathways of insulin removal. Filtrered insulin is internalized by by endocytosis and thereafter degraded into amino acids into the peritubular vessls. Insulin removed from postglomerular peritubular vessels binds to the contraluminal cell membrave. This process in both receptor and non-reveprot mediated. (Adapted from Rabkin R et al. The renal metabolism of insulin. Diabetoligia 1984; 27: 351-357).

In patients with advanced renal failure basal plasma levels of insulin, proinsulin and C-peptide are elevated. The renal clearance of C-peptide is greater than of insulin in renal insufficiency, therefore the use of C-peptide concentration as an index of insulin secretion in these patients is no accurate12,15. During the early phase of renal insufficiency, impaired renal insulin clearance is due to reduced renal blood flow, but as renal function declines, the effect of reduced blood flow is aggravated by a decline of tissue extraction of insulin13. As renal failure progresses, peritubular insulin uptake increases. This compensates for the decline in degradation of filtered insulin until the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decreases to less than about 20 ml/min, after which insulin clearance decreases, the half-life of insulin increases, and overall requirements for insulin decline12,16–18. There is evidence from animal studies that renal failure suppresses insulin metabolism in extrarenal sites, e.g. in skeletal muscles and in the liver. Insulin-dependent diabetic patients often occur a decrease in insulin requirement, and in some patients with residual β cell function, the need for exogenous insulin may disappear19. Some patients with endstage renal disease and hemodialysis occur hypoglycemia because of prolonged persistence of circulating insulin, altered dietary and exercise patterns20.

Under normal circumstances, the capacity of renal tubules to absorb filtered insulin is enormous and saturation does not occur, therefore insulin clearance normally is constant over a wide range of insulin concentration.

The role of insulin resistance

Patients with renal failure have impaired insulin sensitivity with consequent abnormal glucose metabolism. The underlying mechanism is not clear, but an increase of gluconeogenesis in the liver, reduction of hepatic and/or skeletal muscle glucose uptake and an impairment of the intracellular glucose metabolism due either to decreased oxidation to carbon dioxide and water or to diminished synthesis of glycogen may be involved18,21,22. The exact mechanism of insulin resistance in diabetics with renal failure is still debated. There are some controversies in the literature, but experimental and clinical studies indicate that in uremia glucose production and uptake in the liver are normal and that skeletal muscle is the primary site of insulin resistance18,23. Moreover glucogen synthesis abnormality seems to be of great importance, as the rate of glucose oxidation is relatively normal.

Other factors contributing to insulin resistance in uremic patients are an accumulation of uremic toxins and an excess of parathyroid hormone. The role of uremic toxins was supported by the observation that hemodialysis improved insulin sensitivity24–26. Some studies have also shown that intravenous therapy with calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D) and hyperparathyroidism therapy enhanced insulin sensitivity and improved glucose tolerance. Decreased tissue oxygen delivery because of anemia also contributes to insulin resistance in uremia as evidenced by significant increase in insulin sensitivity after correction of anemia by erythropoietin27,28.

Insulin secretion in renal failure

As glomerular filtration decreases below 50 ml/min insulin secretion seems to be blunted and this is probably due to the presence of metabolic acidosis, the parathyroid hormone excess that contribute to the elevation of intracellular calcium concentration and decrease of the cellular content of ATP and Na-K-ATPase pump activity in the pancreatic β cells. Experimental studies have shown that this changes may be prevented by prior parathyroidectomy or by the administration of the calcium channel blocker verapamil and that the effect of metabolic acidosis to insulin secretion may be reversed by hemodialysis23,29–31.

There are some controversies about the effect of erythropoietin therapy on insulin secretion. Some studies showed increase of insulin secretion and decrease of blood glucose levels after a test meal and other studies showed no change in insulin secretion after an oral glucose load32,33.

Insulin requirements in diabetes mellitus with renal disease

Insulin requirements show a biphasic course in patients with diabetes and renal disease. In the beginning glucose control deteriorates because of insulin resistance, therefore more insulin is needed to achieve glycemic control. In advanced renal failure with creatinine clearance below 50 ml/min, the need for insulin is lower or even the cessation of insulin may be necessary. The need for insulin is decreased because of less caloric intake in uremic patients. With the institution of hemodialysis the need for insulin changes because the insulin sensitivity and liver metabolism improve23,34,35.

In both non-diabetic and diabetic subjects with chronic renal failure spontaneous hypoglycemia may develop because of decreased caloric intake, reduced renal gluconeogenesis, impaired release of counterregulatory hormone epinephrine due to the autonomic neuropathy, concurrent hepatic disease, and decreased metabolism of drugs that might promote a reduction in plasma glucose concentrations such as alcohol, nonselective blockers, and disopyramide23,36,37. The plasma elimination half-time is significantly increased in patients with renal insufficiency when clereance of creatinine is below 40ml/min, therefore in these patients the dose adjustment of disopyramide is necessary.

Glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus and renal failure

Measurement of the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) seems to be the most accurate method to assess glycemic control in patients with diabetes. However there are some limitations in patients with renal insufficiency, due to interference from carbamylated hemoglobin that leads to false elevations in the HbA1c level. Other factors that affect the accuracy of the HbA1c measurement are reduced red blood cell life span, recent transfusion, iron deficiency, accelerated erythropoesis due to erythropoietin therapy, and metabolic acidosis38–43. Despite this limitations results on the range of six to seven percent appear to estimate glycemic control similarly to patients without advanced kidney disease, while values over 7.5% may overestimate the extent of hyperglycemia.

Self blood glucose monitoring (SMBG) permits estimation of chronic glycemic control. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that patients with type 1 diabetes monitor blood glucose at last three times daily, and type 2 diabetes patients that are treated with insulin or oral hypoglycemic drugs monitor blood glucose daily44,45. Self-blood glucose monitoring is especially important in type 1 diabetes, because their blood glucose concentrations are less stable from day to day than are those in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Fasting blood glucose levels < 140 mg/dl, < 200 mg/ dl one hour after meal and values of HbA1c between 6- 7% in type 1 diabetes and between 7-8% in patients with type 2 diabetes that are on hemodialysis are considered acceptable46.

Excellent glycemic control has not been emphasized as much in diabetic dialysis patients than in those without renal failure because of the possible precipitation of hypoglycemia with aggressive control, especially with fluctuating dietary intake47.

Management of patients with diabetes mellitus and advanced kidney disease

The management of diabetic patients with advanced kidney disease include diet with protein restriction and oral agents or insulin. Patients with renal failure are often confused with the diet recommendations and have the impression that different specialists have contradictory objectives and give opposing nutritional advice.

In patients with type 1 diabetes insulin therapy imposes regularity in food intake and particularly the intake of carbohydrates. A dietary pattern in these patients should include carbohydrate from fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and low-fat milk. Moreover, monitoring carbohydrate whether by carbohydrate counting, exchanges or experienced-based estimation remains a key strategy in achieving glycemic control and maintain a stable body weight.

Most of the patients with type 2 diabetes are obese, with insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion. These patients must be encouraged to loss weight with hypocaloric diet and exercise 48. Protein restriction is in practice replaced by carbohydrates or fat in order to maintain an adequate caloric intake. It has been shown that both short-term and long-term increases in the carbohydrate ratio are accompanied by an improvement in the action of insulin 49. However beyond a threshold of 55% of carbohydrates hypertriglyceridemia may develop. On the other hand increases in the saturated fat ratio was accompanied by the inhibition of insulin action, while the use of monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fats did not rise the insulin resistance50. Therefore it is appropriate to compensate this reduction in protein caloric intake by carbohydrate calories. Patients of both types of diabetes with renal failure should be advised to go on a protein restriction and to compensate the loss in calories by carbohydrates. The dietary management in these patients calls for close collaboration between the dietician, the diabetologist and the nephrologist.

Pharmacological treatment of hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes mellitus and advanced kidney disease

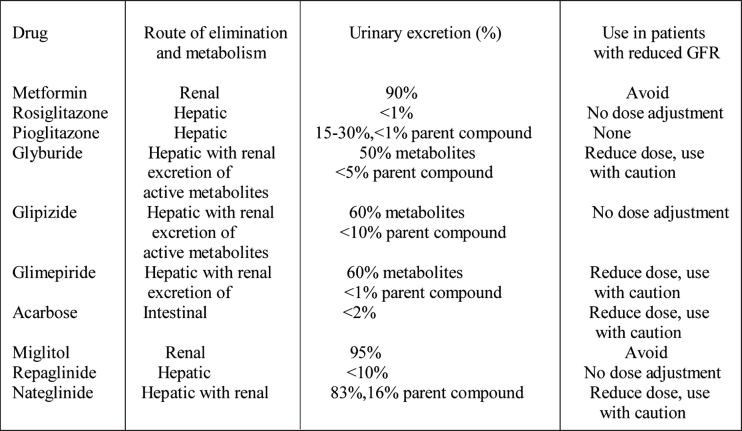

The antihyperglycemic drugs available for the treatment of type 2 diabetes includes secretagogues (sulphonylureas and meglitinides), metformin, -glucosudase inhibitors, the thiazolidinediones (Table 1) and insulin, while patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus are treated with insulin.

Table 1. Oral anti hyperglycemic agents (adapted from RW Snyder and JS Berns, Seminars in Dialysis 2004, Vol 17, No 5, pp 365-370).

Sulphonylureas (Glyburide, Glipizide, Glimepiride) are strongly protein bound, particularly to albumin, therefore elevated drug plasma levels cannot be efficiently reversed by hemodialysis. The administration of these drugs in patients with end-stage renal disease requires careful attention to dosing and the routes of elimination.51 .

Glyburide has weak metabolites that are excreted in the urine and accumulate in patients with renal failure. This drug can be given at reduced dose if the GFR is above 50 ml/min, but should be avoided in more sever renal impairment.

Glipizide is metabolized in the liver into several inactive metabolites. Less than 10% of a dose of Glipizide is excreted unchanged in urine and about 60% is excreted as metabolites. Glipizide metabolites accumulate in patients with renal failure and, one of them may have small amount of activity, that does not cause hypoglycemia. Moreover, Glipizide clearance and elimination half-life is short (two to four hours), therefore dose adjustment in patients with reduced GFR is not necessary. Glipizide should probably be the sulphonylurea of choice in patients with renal failure, but this drug is not available in Greek market at present time.

Glimepiride is metabolized in the liver, the elimination half-time is about 5-8 hours and about 60% of a dose appears in the urine. Virtually all of the urinary excretion is as metabolites that accumulate in patients with renal failure. Glimepiride may cause prolonged hypoglycemia in patients with renal dysfunction, so the drug should be used cautiously, and the dose of this drug must be reduced in patients with a reduced GFR.

Repaglinide is a drug that is exclusively metabolized in the liver, with a half-elimination life 0.6-1.8 hours and is excreted in the bile and stool. Only 10% of the total dose appears in urine, while drug concentration and elimination half-life are increased in patients with renal failure and on dialysis. Nevertheless, dose reduction is not necessary in these patients54.

Nateglinide, is a drug with hepatic metabolism and elimination half-life of about 1.2-1.8 hours. Several of the metabolites are active and accumulate and in patients with impaired renal function causing hypoglycemia. Therefore this drug should be used cautiously in such patients55,56.

Metformin is primary excreted unchanged in the urine. Patients with renal failure are more susceptible to drug accumulation and lactic acidosis. Therefore this drug is contraindicated when creatinine creatinine clearance is below 60 ml/min51.

The thiazolidinediones (Pioglitazone, Rosiglitazone) are virtually completely metabolized in the liver, each forming several metabolites. For both drugs there is no accumulation of the parent drug or the major metabolites in the setting of renal insufficiency. These drugs may cause fluid retention and congestive heart failure. Plasma volume increases in patients treated with thiazolidinediones with consequent anemia due to hemodilution. The risk for edema is more prominent when these drugs are used in patients in combination with insulin51,57,58. Given the risk of edema formation and heart failure these drugs should be avoided in patients with advanced kidney disease, especially if they have preexisting heart failure. Whether these drugs should be avoided in patients on dialysis is uncertain.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors such as acarbose or miglitol are renally excreted with an increased accumulation in renal dysfunction and are contraindicated in patients with renal failure51

Use of insulin in chronic renal failure

Chronic renal failure is associated with decreased renal and hepatic metabolism of insulin. With decreased clearance and metabolism of insulin, the metabolic effects of insulin preparations persist longer and the risk for hypoglycemia increases. According to current recommendations no dose adjustment is required if the GFR is above 50 ml/min. The insulin dose should be reduced to approximately 75% when the GFR is between 10-50 ml/min and by as much as 50% when the GFR is less than 10 ml/min51,52,59.

It is of great importance that the net effect on glycemic control will vary from patient to patient, therefore dose adjustment may be necessary.

The 2005 K/DOQI guidelines suggest that in patients with end-stage renal disease insulin regimen should be encouraged for glycemic control, and oral antihyperglycemic drugs should be avoided with exception of Glipizide60.

Insulin regimens are the same as in patients without renal insufficiency51,61,62.

The pharmacokinetics of various insulin preparations have not been well studied in patients with varying degrees of renal dysfunction, and there are no absolute guidelines defining appropriate dosing adjustment of insulin that should be made based on the level of GFR 51. In patients with end-stage renal disease some suggest that long-acting insulin preparations should be avoided, while other support that such agents should be used.

Patients treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis or continuous cycler peritoneal dialysis (CAPD and CCPD) can be treated with intraperitoneal insulin. This regimen provides a continuous insulin infusion, eliminates the need for injections and provide a more physiological route of absorption63–65. The disadvantage of this therapy is that there is an additional source of bacterial contamination of dialysate during injection of the insulin into the bags, the need of higher total dose of insulin because of losses of spent dialysate and increased risk of pereitoneal fibroblastic proliferation66 and hepatic subcapsular steatosis63. Moreover the absorption of insulin may significantly vary among patients or may decline over time due to acquired abnormalities in the peritoneal membrane.

In conclusion patients with diabetes mellitus and advanced kidney disease should be treated by diet with protein restriction and, preferably by insulin regimen. Oral hypoglycemic agents should be avoided because of risk of hypoglycemia, with exception of glipizide or repaglinide. Insulin dose should be adjusted on the basis of glucose values obtained by home glucose meters (self blood glucose monitoring). In addition to self-monitoring of blood glucose, while periodic measurement of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) permits estimation of chronic glycemic control.

References

- 1.Grundy SM, Howard B, Smith SJr, Eckel R, Redberg R, Bonow RO. Prevention Conference VI: Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: executive summary: conference proceeding for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105:2231–2239. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013952.86046.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, et al. The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991-1998. JAMA. 1999;282:1519–1522. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.USRDS 1999 annual data report. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease; 1999. US Renal Data System; pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerstein HC. Dysglycaemia: a cardiovascular risk factor. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;40(Suppl):9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(98)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil AW, et al. Association of glycaemia with microvascular and macrovascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee Canadian Diabetes Association 2003 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2003;27(Suppl 2):s21–s23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasslacher C, Ritz E, Wahl P, Michael C. Similar risks of nephropathy in patients with type I or type II diabetes mellitus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1989;4:859–863. doi: 10.1093/ndt/4.10.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritz E, Stefanski A. Diabetic nephropathy in type II diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;27:167–194. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90538-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabkin R, Ryan MP, Duckworth WC. The renal metabolism of insulin. Diabetologia. 1984;27:351–357. doi: 10.1007/BF00304849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrannini E, Wahren J, Faber OK, Felig P, Binder C, DeFronzo RA. Splanchnic and renal metabolism of insulin in human subjects: a dose-response study. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:E517–E527. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1983.244.6.E517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubenstein AH, Mako ME, Horowitz DL. Insulin and the kidney. Nephron. 1975;15:306–326. doi: 10.1159/000180518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabkin R, Simon NM, Steiner S, Colwell JA. Effect of renal disease on renal uptake and excretion of insulin in man. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:182–187. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197001222820402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz AI, Rubenstein AH. Metabolism of proinsulin, insulin and C-peptide in rat. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:1113–1121. doi: 10.1172/JCI107277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaspen JB, Mako ME, Kuzuya H, Blix PM, Horowitz DL, Rubenstein AH. Abnormalities in circulating beta cell peptides in chronic renal failure: comparison of C-peptide, proinsulin and insulin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1977;45:441–446. doi: 10.1210/jcem-45-3-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rave K, Heise T, Pfutzner A, Heinemann L, Sawicki PT. Impact of diabetic nephropathy on pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of insulin in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:886–890. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biesenbach G, Raml A, Schmekal B, Eichbauer-Sturm G. Decreased insulin requirement in relation to GFR in nephropathic type 1 and insulin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 2003;20:642–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mak RH, DeFronzo RA. Glucose and insulin metabolism in uremia. Nephron. 1992;61:377–382. doi: 10.1159/000186953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maack T, Johnson V, Kan ST, Figueiredo J, Sigulem D. Renal filtration, transport and metabolism of low molecular weight proteins: a review. Kidney Int. 1979;16:251–270. doi: 10.1038/ki.1979.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg AP, Hagberg JM, Delmez JA, Haynes ME, Harter HR. Metabolic effects of exercise training in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1980;18:754–761. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvestrand A. Carbohydrate and insulin metabolism in renal failure. Kidney Int. 1997;62(52Suppl):S48–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carone FA, Peterson DR. Hydrolysis and transport of small peptides by the proximal tubule. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:F151–158. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1980.238.3.F151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adrogu HJ. Glucose homeostasis and the kidney. Kidney Int. 1992;42:1266–1272. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mak RH. Intravenous 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol corrects glucose intolerance in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1992;41:1049–1054. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kautzsky-Willer A, Pacini G, Barnas U, et al. Intravenous calcitriol normalizes insulin sensitivity in uremic patients. Kidney Int. 1995;47:200–206. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin S, Lin Y, Lu K, et al. Effects of intravenous calcitriol on lipid profiles and glucose tolerance in uraemic patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Clin Sci. 1994;87:533–538. doi: 10.1042/cs0870533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borissova AM, Djambazova A, Todorov K, Dakovska L, Tankova T, Kirilov G. Effect of erythropoietin on the metabolic state and peripheral insulin sensitivity in diabetic patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8:93–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a092282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mak RH. Effect of recombinant human erythropoietin on insulin, amino acid, and lipid metabolism in uremia. J Pediatr. 1996;129:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fadda GZ, Hajjar SM, Perna AF, Zhou XJ, Lipson LG, Massry SG. On the mechanism of impaired insulin secretion in chronic renal failure. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:255–261. doi: 10.1172/JCI114979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perna AF, Fadda GZ, Zhou XJ, Massry SG. Mechanisms of impaired insulin secretion after chronic excess of parathyroid hormone. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:F210–206. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.259.2.F210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh H, Fadda GZ, Smogorzewski M, Liou HH, Massry SG. Abnormal leucine-induced insulin secretion in chronic renal failure. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:F853–860. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.5.F853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kokot F, Wiecek A, Grzeszczak W, Klin M, Zukovska-Szczechowska E. Influence of erythropoietin treatment on glucose tolerance, insulin, glucagon, gastrin, and pancreatic polypeptide secretion in hemodialyzed patients with end stage renal disease. Contrib Nephrol. 1990;87:42–51. doi: 10.1159/000419478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chagnac A, Weinstein T, Zevin D, et al. Effects of erythropoetin on glucose tolerance in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 1994;42:398–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Runyan JW, Hurwitz D, Robbins SL. Effect of Kimmelstiel-Wilson syndrome on insulin requirements in diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1955;252:388–391. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195503102521004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinrauch LA, Healy RW, Leland OS, Jr, et al. Decreased insulin requirements in acute renal failure in diabetic nephropathy. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138:399–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peitzman SJ, Agarwal BN. Spontaneous hypoglycemia in end stage renal failure. Nephron. 1977;19:131–139. doi: 10.1159/000180877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arem R. Hypoglycemia associated with renal failure. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1989;18:103–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ansari A, Thomas S, Goldsmith D. Assessing glycemic control in patients with diabetes and end-stage renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:523–531. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Boer MJ, Miedema K, Casparie AF. Glycosylated haemoglobin in renal failure. Diabetologia. 1980;18:437–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00261697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott MG, Hoffman JW, Meltzer VN. Effects of azotemia on results of the boronate-agarose affinity method and in exchange methods for glycated hemoglobin. Clin Chem. 1984;30:896–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wettre S, Lundberg M. Kinetics of glycosylated hemoglobin in uremia determined on ion-exchange and affinity chromatography. Diabetes Res. 1986;3:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paisey R, Banks R, Holton R, et al. Glycosylated haemoglobin in uraemia. Diabet Med. 1986;3:445–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1986.tb00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joy MS, Cefalu WT, Hogan SL, Nachman PH. Long-term glycemic control measurements in diabetic patients receiving hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:297–307. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.30549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldstein DE, Little RR, Lorenz RA, Malone JI, Nathan D, Peterson CM. Test of glycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S91–S93. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Position statement. Standard of Medical Care in Diabetes-2007. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:s4–s41. doi: 10.2337/dc07-S004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tzamaloukas AH, Murata GH, Zager PG, Eisenberg B, Avasthi PS. The relationship between glycemic control and morbidity and mortality for diabetics on dialysis. ASAIO J. 1993;39:880–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tzamaloukas AH. The use of glycosylated hemoglobin in dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 1998;11:143–147. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gin H, Rigaleau V, Aparicio M. Which diet for diabetic patients with chronic renal failure? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2577–2579. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.11.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gin H, Aparicio M, Aubertin J. Low protein and low phosphorus diet in patients with chronic renal failure: influence on glucose tolerance and tissue-insulin sensitivity. Metabolism. 1987;11:1080–1085. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(87)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gin H, Rigalleau V, Aparicio M. Which diet for diabetic patients with chronic renal failure? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2577–2579. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.11.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Snyder RW, Berns JS. Use of insulin and oral hypoglycemic medications in patients with diabetes mellitus and advanced kidney disease. Semin Dial. 2004;17:365–370. doi: 10.1111/j.0894-0959.2004.17346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arnoff GR, Berns JS, Brier ME. Drug prescribing in renal failure: dosing guidelines for adults. 4th ed. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skillman TG, Feldman JM. The pharmacology of sulphonylureas. Am J Med. 1981;70:361–372. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90773-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasslacher C. Safety and efficacy of repaglinide in type 2 diabetic patients with and without impaired renal function. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:886–891. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Inoue T, Shibahara N, Miyagawa Ketal. Pharmacokinetics of nateglinide and its metabolites in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus and renal failure. Clin Nephrol. 2003;60:90–95. doi: 10.5414/cnp60090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagai T, Imamura M, Iizuka K, Mori M. Hypoglycemia due to nateglinide in diabetic patient with chronic renal failure. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;59:191–194. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(02)00242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charpentier G, Riveline JP, Varroud-Vial M. Management of drugs affecting blood glucose in diabetic patients with renal failure. Diabetes Metab. 2000;26(Suppl 4):73–85. K/D. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sambanis C, Tziomalos K, Kountana E, et al. Effect of pioglitazone on heart function and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels of patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00592-007-0014-7. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sampanis Ch, Tziomalos K, Kehagia T, et al. Heart failure after thiazolidinedione therapy. Hippocratia. 2005;9:8–91. [Google Scholar]

- 60.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;4(Suppl 3):S1–S360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tunbridge FK, Newens A, Home PD, et al. A comparison of human ultralente- and lente-based twice-daily injection regimens. Diabet Med. 1989;6:496–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1989.tb01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Freeman SL, OBrien PC, Rizza RA. Use of human ultralente as the basal insulin component in treatment of patients with IDDM. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1991;12:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(91)90076-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Diaz-Buxo JA. Blood glucose control in diabetics: I. Semin Dial. 1993;6:392–397. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Daniels ID, Markell MS. Blood glucose control in diabetics: II. Semin Dial. 1993;6:394–399. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tzamaloukas AH, Oreopoulos DG. Subcutaneous versus intraperitoneal insulin in the management of diabetics on CAPD: a review. Adv Perit Dial. 1991;7:81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Selgas R, Lopez-Riva A, Alvaro F, et al. Insulin influence on the mitogenic-induced effect of the peritoneal effluent in CAPD patients used as an additive to dialysate. Adv Perit Dial. 1989;5:161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]