Abstract

A new photocaged nucleoside was synthesized and incorporated into DNA using standard synthesis conditions. This approach enabled the disruption of specific H-bonds and allowed for the analysis of their contribution to the activity of a DNAzyme. Brief irradiation with non-photodamaging UV light led to rapid decaging and almost quantitative restoration of DNAzyme activity. The developed strategy has the potential to find widespread application in the light-induced regulation of oligonucleotide function.

Many recent discoveries have revealed the multifactorial roles oligonucleotides play in vitro and in vivo. It has been demonstrated, that they can act as catalysts (ribozymes and DNAzymes),1, 2 sensors (aptamers),3 gene expression platforms (riboswitches and antiswitches),4, 5 and gene regulatory elements (antisense DNA, siRNA, and miRNA).4, 6

In order to study the function of oligonucleotides in a detailed fashion and to employ them as highly specific biological research tools, precise control over their activity in a spatial and a temporal manner is required. In this context, light represents an ideal control element since it can be precisely controlled in amplitude, location, and timing thus imposing spatio-temporal control on the system under study.7 The most common technique of conveying light-regulation to biological processes involves the installation of a photo-protecting group on a biologically active molecule which can be completely removed via light irradiation. This process, termed ‘caging’, has been successfully employed to the light-controlled activation of small molecule inducers of gene expression, fluorophores, peptides, and proteins.7 DNA and RNA have been caged as well, mostly through statistical reaction of the phosphate backbone of the synthesized or transcribed oligonucleotide with reactive diazo-derivatives of caging groups.8 The major disadvantage of this approach is that no control over the position and number of installed caging groups can be achieved. Moreover, caging groups are only installed on the phosphate backbone, not on the heterocyclic base itself, failing to disrupt Watson-Crick base pairing. Recently, approaches to the site-specific caging of DNA have been reported. The introduction of a O-4 caged thymidine has been successfully applied to the photochemical activation of transcription and aptamer binding.9 However, due to the lability of the caging group special DNA synthesis conditions were necessary. An adenosine modified with a sterically demanding, photo-removable imidazolylethylthio group has been used to photochemically activate an 8-17E DNAzyme.10 After irradiation for 8-10 min with short-wavelength UV light (254-310nm) only 30% of RNA cleavage was observed after a 60 min reaction time. Since the caging group was installed at C-8, no hydrogen bonding of the adenosine was disrupted. Reversible switching of DNAzyme activity was previously achieved through incorporation of diazobenzene motifs, however, only a 5- to 9-fold rate modulation upon irradiation was obtained.11

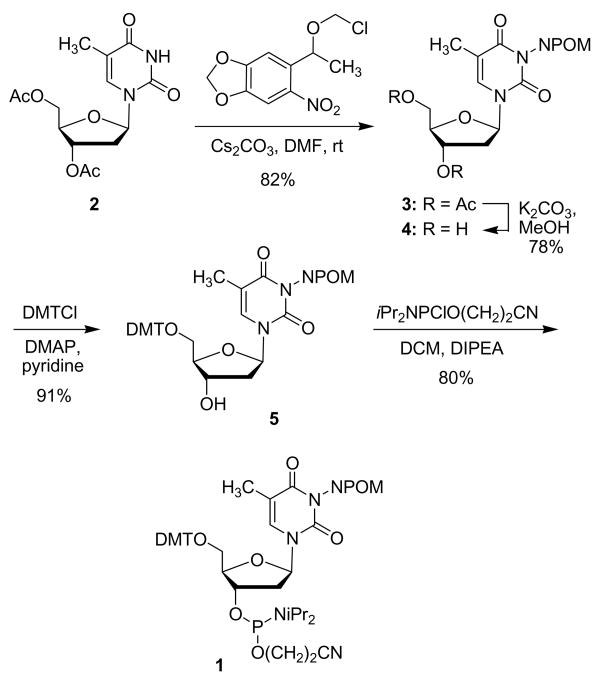

Our goal was to develop a caging approach which fulfills all of the following requirements: a) allows for specific probing of hydrogen bonding of oligonucleotide bases, b) enables introduction of the caged monomer under standard DNA synthesis conditions, c) provides a caged oligomer which is stable to a wide range of chemical and physiological conditions, and d) allows for excellent restoration of DNA activity upon brief irradiation with non-photodamaging UV light. Recently, we developed a new caging group (NPOM = 6-nitropiperonyloxymethyl) which proved to be highly efficient in the caging of nitrogen heterocycles.12 This group was specifically designed to solve previous problems associated with chemical stability or slow decaging rates of photo-protecting groups on nitrogen atoms. Here, we report the application of this group to the caging of the thymidine N-3, thus disrupting an essential hydrogen bond. The phosphoramidite 1 (Scheme 1) was synthesized in 5 steps from thymidine starting with the preparation of the known acetylated thymidine 2 (Ac2O, DMAP, 98%).13 Caging with 6-nitropiperonyloxymethyl chloride (NPOM-Cl)12 was achieved in 82% (Cs2CO3, DMF, rt) yielding 3. Removal of the actetate groups (K2CO3, MeOH, 78%) towards 4 followed by selective tritylation of the primary hydroxy group (DMTCl, DMAP, pyridine) delivered 5 in 91% yield. Installation of the phosphoramidite (2-cyanoethyl-diisopropyl-chloro phosphoramidite, DCM DIPEA) was achieved in 80% under classical conditions completing the synthesis of 1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the caged phosphoramidite 1.

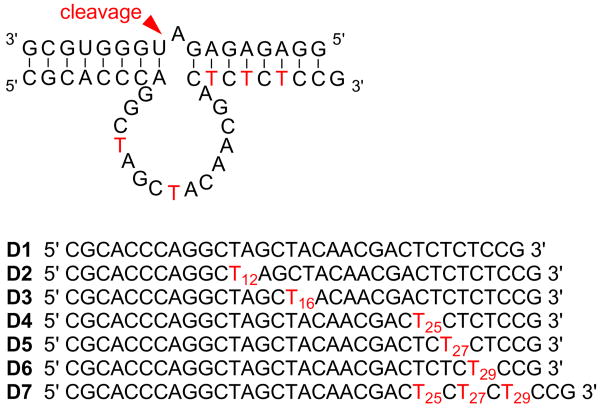

The stability of 1 to DNA synthesis conditions and its rapid decaging through irradiation with UV light of 356 nm (ε365 = 6887 cm−1 M−1) was demonstrated (see supporting information). The quantum yield (φ = 0.094) for the photochemical removal of the NPOM group was determined by 3,4-dimethoxynitrobenzene actinometry.14 Using standard DNA synthesis conditions 1 has been incorporated at all thymidine positions of the 10-23 DNAzyme D1 providing the mutants D2-D7 (Figure 1). The 10-23 DNAzyme is a highly active and sequence specific RNA cleaving deoxyoligonucleotide.2, 15 It has been successfully applied to the suppression of genes in vitro and in model organisms.16

Figure 1.

10-23 DNAzyme bound to its RNA substrate; thymidines are highlighted in red. Wild-type DNAzyme D1 and DNAzymes D2-D7 having 1 incorporated at various thymidine positions.

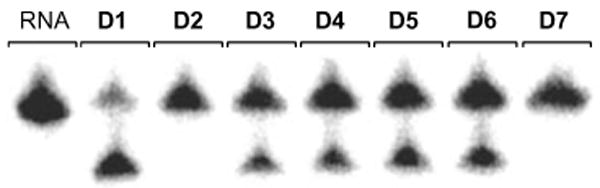

To probe the necessity of free 3-NH groups in these thymidine residues for the maintenance of DNAzyme activity, the RNA substrate 5′-GGAGAGAGAUGGG-UGCG-3′ was radioactively 5′-labeled using 32P-ATP and exposed to the seven DNAzymes D1-D7 in a standard reaction buffer (100 mM MgCl2, pH 8.2, 15 mM Tris buffer) for 30 min at 37°C (Figure 2). As expected, the original 10-23 DNAzyme D1 led to almost complete RNA cleavage. DNAzyme D2 exhibited completely inhibited activity due to the installation of a single caging group on T12. This was expected, since a previous mutagenesis study of the catalytic core revealed this to be an essential residue.17 These experiments also demonstrated that the least essential thymidine residue is located at position 16. This was confirmed through the incorporation of 1 at this position leading to still catalytically active D3, even in presence of the sterically demanding caging group. We then probed the tolerance of base pair mismatches in the substrate recognition domains by caging the thymidine residues T25, T27, and T29. The resulting DNAzymes D4-D6 displayed lower activity but still induced substantial RNA cleavage. Previously, single mismatches between the RNA substrate and the flanking regions have led to reduced cleavage activity as well.15 However, selective installation of three caging groups on T25, T27, and T29 lead to complete inhibition of RNA cleavage activity in D7, presumably due to the disruption of multiple Watson-Crick base paring interactions with the substrate.

Figure 2.

Cleavage of the RNA substrate for 30 min with the 10-23 DNAzymes D1-D7 without prior UV irradiation. 100 mM MgCl2, pH 8.2, 15 mM Tris buffer, 37 °C, 40 nM substrate, 400 nM enzyme.

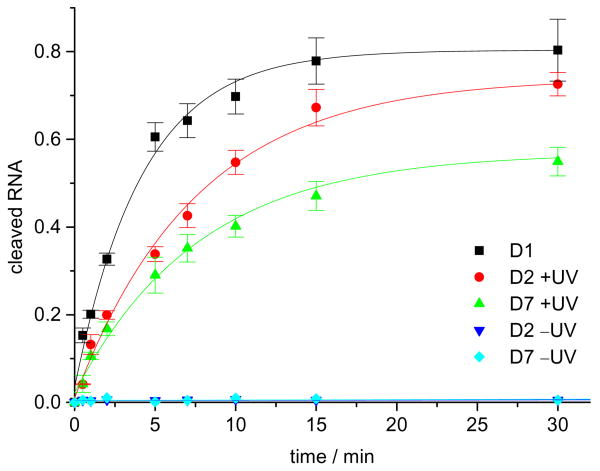

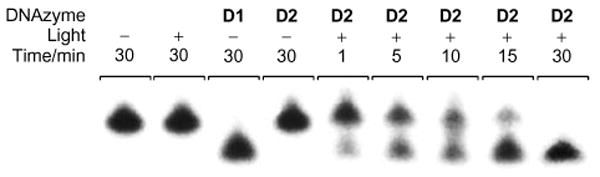

Subsequently, a more detailed time-course investigation of the light-activation of D2 was conducted (Figure 3). A control experiment of just the RNA substrate exposed to UV light did not result in any cleaved product. Complete cleavage of the RNA substrate was achieved within 30 min using the unmodified D1, whereas no cleavage was observed with caged D2 under identical conditions. However, brief irradiation with non-photodamaging UV light of 365 nm (25 W) for 1 min initiated decaging and activation of D2. Figure 3 displays the resulting RNA cleavage with complete consumption of the substrate by 30 min.

Figure 3.

Progressing cleavage of the RNA substrate with the 10-23 DNAzyme D2 after a 1 min UV irradiation (365 nm). Complete RNA cleavage is observed after 30 min. 100 mM MgCl2, pH 8.2, 15 mM Tris buffer, 37 °C, 40 nM substrate, 400 nM enzyme.

In order to determine the cleavage rates k of the DNAzymes D1, D2, and D7, the amount of cleaved RNA was quantified at nine different time points under single-turnover conditions through integration (using Molecular Dynamics ImageQuant 5.2™) of the corresponding radioactive bands in 15% denaturing TBE polyacrylamide gels using a PhosphorImager (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cleavage of the RNA substrate with the wild-type DNAzyme D1 and the caged DNAzymes D2 and D7 (with and without UV irradiation). 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4, 15 mM Tris buffer, 37 °C, 40 nM substrate, 400 nM enzyme. The cleaved RNA has been normalized and the experiments were conducted in triplicate.

The data was fitted (using Microcal Origin 5.0™) with an exponential decay curve ∼ –ekt),18 and, as previously observed, the wild-type DNAzyme D1 showed a high cleavage rate (kD1 = 0.242±0.013 min−1) under the assay conditions. As expected from the results shown in Figure 2, the caged DNAzymes D2 and D7 displayed no cleavage activity (kD2 = ND and kD7 = ND), demonstrating that caging group installation on thymidine can completely abrogate both catalytic activity and substrate binding. Gratifyingly, brief irradiation for 1 min (365 nm, 25 W) of the caged DNAzymes led to restoration of catalytic acitivity of D2 (kD2,UV = 0.131±0.007 min−1) and D7 (kD7,UV = 0.129±0.011 min−1) to 54% and 53% of the original D1 activity, respectively. After a 30 min incubation time 80% of the RNA substrate was cleaved by D1, 73% by irradiated D2, and 55% by irradiated D7. Thus DNAzymes with an excellent light-triggered switch have been developed.

In summary, we synthesized a new photocaged nucleoside, which was incorporated into DNA using standard synthesis conditions. This caging approach was then used to probe the necessity of specific hydrogen bonds for activity of a DNAzyme, and we found that disruption of a single H-bond can be sufficient to completely inhibit the enzyme. Surprisingly, installation of the bulky caging group was tolerated at several positions within the DNAzyme and the caging of three thymidine residues was necessary to abrogate binding to the RNA substrate. Restoration of DNAzyme activity was achieved through decaging with a brief irradiation of 365 nm UV light (UVA light of this wavelength is far less toxic to cells than UVB light of shorter wavelenght and is typically considered to be non-photodamaging7c,19), providing an excellent on/off switch for oligonucleotide activity.

We believe that the photocaged phosphoramidite 1 will find widespread application in the light-induced regulation of oligonucleotide function. Most importantly, caged DNAzymes could allow for the spatio-temporal control of gene suppression in model organisms, thus providing powerful tools for functional genomics studies.

Supplementary Material

Synthesis and analytical data of 1-5 and D1-D7, enzyme assay protocols, and enzyme decaging study. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support by the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation (grant 5-FY05-1215), and the Department of Education (GAANN Fellowship for D.D.Y.). DNA synthesis was conducted in the Biomolecular Resource Facility of the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest University, supported in part by NIH grant P30 CA-12197-30. We also thank Dr. Richard Pon, University of Calgary, for his advice on the DNA incorporation of 1.

References

- 1.Doudna JA, Cech TR. Nature. 2002;418:222. doi: 10.1038/418222a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santoro SW, Joyce GF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breaker RR. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002;13:31. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breaker RR. Nature. 2004;432:838. doi: 10.1038/nature03195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Mandal M, Breaker RR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:451. doi: 10.1038/nrm1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bayer TS, Smolke CD. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:337. doi: 10.1038/nbt1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Scherer LJ, Rossi JJ. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1457. doi: 10.1038/nbt915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Nature. 1998;391:806. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Young DD, Deiters A. Org Biomol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1039/b616410m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tang X, Dmochowski IJ. Mol BioSyst. 2007 doi: 10.1039/b614349k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Goeldner M, Givens R. Dynamic Studies in Biology: Phototriggers, Photoswitches and Caged Biomolecules. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. p. xxvii. [Google Scholar]; (d) Mayer G, Heckel A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4900. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Dorman G, Prestwich GD. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:64. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lawrence DS. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:570. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Shah S, Rangarajan S, Friedman SH. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:1328. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ando H, Furuta T, Tsien RY, Okamoto H. Nat Genet. 2001;28:317. doi: 10.1038/ng583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Krock L, Heckel A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:471. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Heckel A, Mayer G. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:822. doi: 10.1021/ja043285e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ting R, Lermer L, Perrin DM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12720. doi: 10.1021/ja046964y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Liu Y, Sen D. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:887. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keiper S, Vyle JS. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:3306. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lusic H, Deiters A. Synthesis. 2006:2147. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saladino R, Crestini C, Occhionero F, Nicoletti R. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:3607. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Zhang JY, Esrom H, Boyd IW. Appl Surf Sci. 1999;139:315. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pavlickova L, Kuzmic P, Soucek M. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 1986;51:368. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santoro SW, Joyce GF. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13330. doi: 10.1021/bi9812221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cairns MJ, Saravolac EG, Sun LQ. Curr Drug Targets. 2002;3:269. doi: 10.2174/1389450023347722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaborowska Z, Furste JP, Erdmann VA, Kurreck J. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cairns MJ, King A, Sun LQ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2883. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Robert C, Muel B, Benoit A, Dubertret L, Sarasin A, Stary A. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:721. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12345616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schindl A, Klosner G, Honigsmann H, Jori G, Calzavara-Pinton PC, Trautinger F. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998;44:97. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(98)00127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Synthesis and analytical data of 1-5 and D1-D7, enzyme assay protocols, and enzyme decaging study. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.