Abstract

The Lewis acid-mediated reactions of substituted cyclopropanone acetals with alkyl azides were found to strongly depend on the structure of the ketone component. When cyclopropanone acetal was treated with alkyl azides, N-substituted 2-azetidinones and ethyl carbamate products were obtained, arising from azide addition to the carbonyl, followed by ring expansion or rearrangement, respectively. When 2,2-dimethylcyclopropanone acetals were reacted with azides in the presence of BF3•OEt2, the products obtained were α-amino-α′-diazomethyl ketones, which arose from C2–C3 bond cleavage of the corresponding cyclopropanone, giving oxyallyl cations, that were captured by azides. Aryl-substituted cyclopropanone acetals, when subjected to these conditions, afforded [1,2,3]oxaborazoles exclusively, which were also the result of C2–C3 bond rupture, azide capture and then loss of nitrogen. In the reactions of n-hexyl-substituted cyclopropanone acetals with alkyl azides, a mixture of 2-azetidinones and regioisomeric [1,2,3]oxaborazoles were obtained. The reasons for the different behavior of the various systems is discussed.

Cyclopropanones display unusual properties arising from the incorporation of the carbonyl group into a strained three-membered ring.1 Initially, cyclopropanones attracted interest due to their role as intermediates in Favorskii rearrangements.2 Since then, there have been numerous experimental and theoretical studies aimed at understanding the nature of cyclopropanone reactivity.3 Inherently reactive, cyclopropanones are usually generated in situ from the corresponding hemiketals (or their derivatives), which are readily synthesized and easily handled (Scheme 1).4 In general, the chemistry of cyclopropanones is dominated by ketone addition or ring-opening to form oxyallyl cations.5 The latter species can be trapped with a nucleophile6 or cyclized with a dipolarophile to give bicyclic ketones.7

Scheme 1.

In the 1970’s, Wasserman et al. showed that cyclopropanones react with sodium azide, to afford β-lactams (Scheme 2).8 This reaction presumably proceeds due to the release of strain upon ring expansion coupled with the generation of nitrogen as the byproduct. Our group has previously studied the intermolecular reaction of alkyl azides with cyclic ketones, which generally leads to ring-expanded lactams in a process reminiscent of the Schmidt reaction.9 Following Wasserman, we were initially interested in reacting cyclopropanones with alkyl azides under Lewis acidic conditions as a means of synthesizing N-substituted β-lactams. In the course of this study, we discovered that the Lewis acid promoted reactions of azides and cyclopropanones provide a rich array of products that depend on the nature of the cyclopropanone substitution. Previously, we disclosed that the reactions of 2,2-dimethylcyclopropanone equivalents with azides provide α-amino-α2-diazomethyl ketones.10 Herein, we describe the results of a broader investigation on the reactions of substituted cyclopropanones with alkyl azides. In so doing, we describe several previously unknown reaction pathways that result from both C1/C2 and C2/C3 bond rupture of the cyclopropanone reactant. The mechanisms of the various reactions will also be discussed.

Scheme 2.

Results

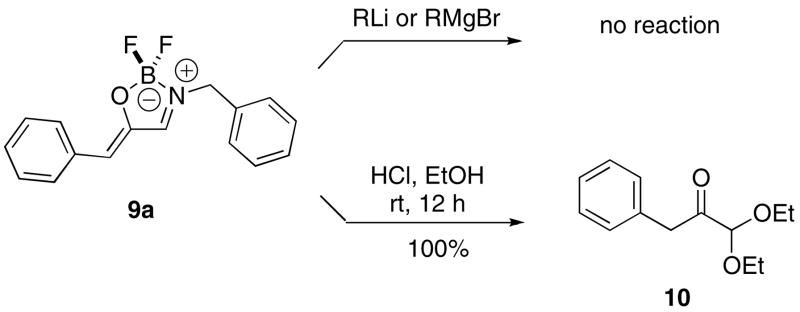

Cyclopropanone proper

As noted above, the present study began as an attempt to make N-substituted β-lactams through azide-mediated ring-expansion processes.9 To this end, a mixture of cyclopropanone hemiketal and alkyl azide were allowed to react in the presence of BF3•OEt2. Although the expected ring-expanded β-lactams 2 were consistently formed in 27–58% yield, a significant amount of ethyl carbamate product of type 3 was also observed in every case (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reactions of Cyclopropanone Acetal 1 with Azides

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | product (yield, %) | |

| A | C6H5CH2 | 2a (45) | 3a (13) |

| b | n-C6H14 | 2b (58) | 3b (40) |

| c | 3-MeO(C6H4)CH2 | 2c (36) | 3c (60) |

| d | 4-MeO(C6H4)CH2 | 2d (27) | 3d (35) |

| e | 4-MeO2C(C6H4)CH2 | 2e (38) | 3e (43) |

| f | 4-Br(C6H4)CH2 | 2f (45) | 3f (34) |

In an effort to increase the β-lactam yield, a variety of acids such as TiCl4, SnCl4, BF3•OEt2, TfOH, and TFA were surveyed. Only BF3•OEt2 was found to reproducibly provide the desired products, although TFA also gave very low yields of β-lactam and ethyl carbamate. The highest yields were obtained when 2.5 equiv of BF3•OEt2 was used. Although the combined yield of β-lactam and carbamates was good to excellent for the series of alkyl azides examined (51–98% combined), we were unable to obtain β-lactam products to the exclusion of carbamate products, which in several cases were the major products.

In the case of β-lactam formation, typical azido-Schmidt chemistry is at work: the azide attacks the ketone and the ensuing azidohydrin collapses with the loss of nitrogen and concomitant ring expansion to give β-lactams 2 (Scheme 3).9

Scheme 3.

The ethyl carbamates 3 could arise from an azidohydrin intermediate that, instead of bond migration, undergoes ring-opening to give a carbocation. This step is analogous to the well-known cyclopropylcarbinyl cation homoallylic rearrangement.11 Pirrung’s work in the study of ethylene biosynthesis invokes a similar carbocation intermediate derived from 1-aminopropanecarboxylic acid, which fragments to produce ethylene.12 Loss of ethylene provides an isocyanate which reacts with ethanol to give the product. Other mechanisms that include concerted cheletropic elimination of ethylene (not shown) could also be envisioned. We did not pursue extensive mechanistic study of this interesting, if not especially useful, process.

2,2-Dimethylcyclopropanone

To extend the above study to encompass differently substituted cyclopropanones, we treated triethyl(1′-methoxy-2′,2′-dimethylcyclopropoxy)silane 4 with 2.0 equiv of benzyl azide and 1.0 equiv of BF3•OEt2 in CH2Cl2 (−78 °C to rt, 12 h).10 Workup followed by chromatography provided two products, neither of which was the β-lactam or carbamate anticipated from the previous study. Specifically, the IR spectra lacked the characteristic carbonyl β-lactam stretching frequency at ca. 1740 cm−1, but instead had two strong absorbances at 2099 and 1633 cm−1. In addition, the 13C NMR spectrum contained a ketone signal at 201 ppm and the mass spectrum indicated the retention of all three nitrogen atoms in the major product. Unfortunately, the 1H NMR spectrum provided almost no connectivity information, consisting almost entirely of singlets at 1.3, 3.7, and 6.0 ppm. In contrast, the minor product, (in 4% yield) was readily identified as the known N-benzyl-2,2-dimethyl-3-azetidinone13 by NMR and IR spectroscopy. In particular, the IR spectrum contained a prominent absorption at 1840 cm−1, while the 13C NMR spectrum contained a carbonyl resonance at 209.1 ppm. After some experimentation, the identity of the major product was confirmed through X-ray crystallographic analysis of the product isolated from the reaction of cyclopropanone acetal 4 with p-carbomethoxybenzyl bromide (5c, Table 2).

Table 2.

Reactions of Azides with Cyclopropanone Acetal 4

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | products (yield, %) | |

| a | C6H5CH2 | 5a (47) | 6a (4) |

| b | 4-Br(C6H4)CH2 | 5b (41) | - |

| c | 4-MeO2C(C6H4)CH2 | 5c (46) | - |

| d | 2-napthyl | 5d (38) | 6d (5) |

| e | 9-anthacenyl | 5e (54) | - |

| f | n-C6H14 | 5f (44) | - |

We surveyed a variety of alkyl azides in this reaction. The α-amino-α′-diazomethyl ketones were obtained in ca. 40–50%, but the 3-azetidinone was formed only occasionally and in low yield (Table 2). After a brief survey of acids and various conditions, we found that our initial conditions gave the highest yields and that BF3•OEt2 was the only acid that led to these products, while other conditions resulted only in decomposition of the starting materials.

The retention of all three nitrogen atoms of the alkyl azide in products 5c suggested that this conversion involved the acid-promoted C2–C3 bond cleavage of 2,2-dimethylcyclopropanone to yield the corresponding oxyallyl cation.7,14 We propose that the cation-stabilizing character of the two methyl groups allowed this pathway to predominate over azide addition to the carbonyl.15 The oxyallyl cation could then react with the alkyl azide in several ways (Scheme 4). A stepwise pathway involving nucleophilic attack of the azide on the most-substituted carbon of the oxyallyl cation providing A, followed by electrophilic capture by the azide of the resulting anion, could give rise to the 1,2,3-triazin-5-one intermediate B. In principle, this order of events could also be reversed as azides have both nucleophilic and electrophilic tendencies.16 Intermediate B could also result from a concerted [3 + 3] cycloaddition or from a [3 + 2] cycloaddition of azide with the oxyallyl cation, followed by 1,2-migration of the resulting triazole cation C. Another possibility is that azide attacks at the unsubstituted terminus of the oxyallyl cation followed by allylic transposition, giving rise to A (path c).17 We do not currently have strong evidence to rule out any of these possibilities, although we did attempt to react the bromo silyl enol ether shown in Scheme 5 with benzyl azide under a variety of conditions.18 We were unable to isolate any product from these reactions. Although the intermediacy of C cannot be completely ruled out, we favor the stepwise or concerted formation of B via paths a/a′ due to the observation of similar intermediates under other conditions (see discussion accompanying Scheme 6, below).

Scheme 4.

Scheme 5.

Scheme 6.

In work reported by Pearson, azido-tethered indoles were submitted to acidic conditions to afford triazines incorporated into a complex indole-containing framework.18 Schultz et al. also reported tetracyclic triazines arising from a photo-induced cycloaddition of an azido-tethered quinone.19 Recently, West and coworkers found that Nazarov intermediates derived from dienones could be trapped with pendant azides when treated with BF3•OEt2 leading to a variety of products.20 They propose two possible mechanisms to account for their observations: (1) direct attack of the proximal nitrogen of this azide onto the oxyallyl cation to give a boron enolate diazo cation species or (2) [3 + 3] cycloaddition of the tethered azide with the oxyallyl cation followed by ring opening of the 1,2,3-triazin-5-one to provide the same enolate cation.

We neither observed nor isolated 1,2,3-triazin-5-ones in any of the experiments described. However, their involvement is strongly suggested by the observation of products 5 and 6. We propose that fragmentation of the 1,2,3-triazin-5-one followed by proton transfer gives products 5 (Scheme 4, above). The difference in reactivity between the triazines formed in the present project and those reported by Schultz and Pearson may be ascribed to stabilization of the latter through electronic means or by virtue of their presence in more complex ring systems. We also note that the Schultz experiment was done under photochemical, not Lewis acid-mediated, conditions.

The small amount of 3-azetidinones 6 isolated in two of these reactions could conceivably arise from the direct cyclization reaction of intermediate D or from the acid-promoted decomposition of 5 (Scheme 4). We did not observe formation of 3-azetidinone after isolating ketone 5a and resubmitting it to the acidic reaction conditions for several days, which suggests that 6a and 6d arise directly from D as shown. α-Amino-α′-diazomethyl ketones are known precursors to 3-azetidinones by metallocarbene-mediated NH insertion reactions.20 Therefore, we treated α-amino-α′-diazomethyl ketones 5 with Rh2(OAc)4, which afforded the cyclized products 6 in high yield (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rh2(OAc)4-Catalzyed Cyclization of 5

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | product | yield (%) |

| a | C6H5CH2 | 6a | 90 |

| b | 4-Br(C6H4)CH2 | 6b | 87 |

| c | 4-MeO2C(C6H4)CH2 | 6c | 77 |

| d | 2-napthyl | 6d | 95 |

| e | 9-anthacenyl | 6e | 100 |

| f | n-C6H14 | 6f | 72 |

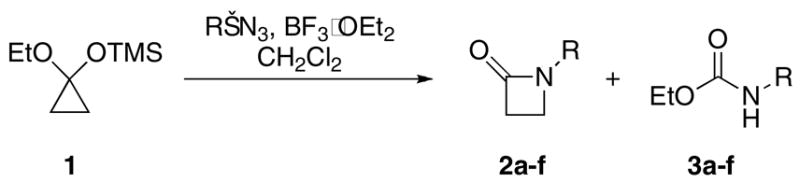

Aryl-substituted cyclopropanones

The observation of ring-opening products from 2,2-dimethyl substituted cyclopropanone, but not from the parent ring system suggested that the former pathway was favored by the ability of the methyl groups to stabilize the oxyallyl cation internediate. If so, we reasoned that a phenyl group might be able to play a similar role. Thus, triethyl(1-methoxy-2-phenyl-cyclopropoxy)silane21 7 was treated with 2.0 equiv of benzyl azide and 1.0 equiv of BF3•OEt2 in CH2Cl2 (−78 °C to rt, 12 h). After NaHCO3 workup and silica gel chromatography, a light yellow solid was obtained. In light of the previous described experiments, we had expected to obtain an α-amino-α′-diazomethyl ketone or a 2- or 3-azetidinone from this experiment. However, the spectral data obtained for the reaction product ruled out all of these possibilities. Both IR and 13C NMR spectra indicated the lack of a carbonyl group. Additionally, the absorbance corresponding to the diazoalkane group at ca. 2100 cm−1 was lacking. Interestingly, the product from this reaction fluoresced strongly under ultraviolet radiation, giving a bright blue spot when irradiated. As before, only reactions promoted by BF3•OEt2 gave the observed products. In particular, other boron-containing Lewis acids including BBr3 and BCl3 did not lead to the formation of any tractable products.

An X-ray crystallographic analysis of the product resulting from reaction of cyclopropanone acetal 8 with phenylethyl azide was performed following recrystallization from Et2O/CH2Cl2. The product obtained was a [1,2,3]oxaborazole in which oxygen and boron form a complex and nitrogen and boron share a coordinate covalent bond. This unusual heterocycle 9 had incorporated a stoichiometric quantity of BF2, readily explaining why using more than 1 equiv of BF3•OEt2 gave better yields and why only boron-based Lewis acids led to formation of this product. These 1,2,3-oxaborazoles proved remarkably stable, surviving chromatography, extended heating, and strongly basic conditions.22 Related heterocycles, such as the examples shown, have been used as fluorescent probes and participate in photo-triggered [2+2] cycloadditions (Figure 1).23

Figure 1.

Examples of known [1,2,3]oxaborazole analogs.

A series of these products was generated in yields ranging from 32–50% when 1.5 equiv of BF3•OEt2 were used. We also noted that both phenyl- and p-methoxyphenyl-substituted cyclopropanone acetals gave comparable yields, suggesting that the electronic differences between these two cyclopropanones did not significantly affect reaction outcome (Table 4). These reactions could be conveniently performed in a microwave reactor (135 °C, CH2Cl2, 10 min) to give the same products in comparable or slightly higher yield in much less time.24 Lastly, variation of the acetal function did not appreciably affect the reaction. Reactions in which the trimethylsilyl acetal or the hemiketal of 7 were used provided the corresponding 1,2,3-oxaborazoles 9 in yields comparable to those employing triethylsilyl acetals (± 5% in each case).

Table 4.

Reactions of Azides with Cyclopropanone Acetals 7 and 8

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | cyclopropanone | R2 | product | yield (%) |

| a | 7 | C6H5CH2 | 9a | 50 |

| b | 7 | 4-Br(C6H4)CH2 | 9b | 40 |

| c | 7 | C6H5CH2CH2 | 9c | 44 |

| d | 7 | n-C 6H14 | 9d | 50 |

| e | 8 | C6H5CH2 | 9e | 40 |

| f | 8 | 4-Br(C6H4)CH2 | 9f | 32 |

| g | 8 | C6H5CH2CH2 | 9g | 30 |

The observation of oxaborazoles is consistent with either a 1,2,3-triazin-5-one intermediate or nucleophilic attack with azide onto the oxyallyl cation, the latter of which directly affords a boron enolate diazonium cation (Scheme 7). The 1,2,3-triazin-5-one, if formed, may then undergo ring opening to form this enolate cation as well. Although azide may add to either terminus of the oxyallyl cation, only oxaborazoles 9 corresponding to azide addition to the unsubstituted terminus were observed. It appears that only one mode of addition is favored (kinetically or thermodynamically) or the azide addition step is reversible and elimination of Ha is faster than elimination of Hb. This regiochemistry issue and the comparison of these results with those obtained from 4 will be discussed below.

Scheme 7.

The 1,2,3-oxaborazoles are formal equivalents of an activated iminium ion and an enolate coordinated by a Lewis acid. We wondered if these compounds might display reactivity characteristic of either species, or conceivably of an amine-stabilized oxyallyl cation.25 With approximately a gram of 1,2,3-oxaborazole 9a at our disposal, a variety of reaction types were surveyed, including reactions with alkyl lithiums, Grignards, carbenes, and dipolarophiles. In only one case was reaction with this heterocycle observed. Thus, subjecting the 1,2,3-oxaborazole 9a to acidic ethanolic conditions furnished the 1,2 keto acetal 10 in ca. 100% yield (Scheme 8).

Scheme 8.

Monoalkyl cyclopropanones

We also examined the analogous reactions of singly substituted cyclopropanone acetals. Thus, we treated trimethyl(1-methoxy-2-heptylcyclopropoxy)silane21 11 with 2.0 equiv of benzyl azide and 1.5 equiv of BF3•OEt2 in CH2Cl2 (−78 °C to rt, 12 h). These conditions did not result in any isolable product or recovery of the starting material. In contrast, heating the components with BF3•OEt2 at 135 °C for 30 min afforded small amounts of β-lactam 12 and 1,2,3-oxaborazole 13. Extensive optimization attempts did not result in greater than ca. 15% total yields (Scheme 9). The reaction products from phenylethyl azide were constitutionally isomeric adducts of the 1,2,3-oxaborazoles 14a (ca. 4:1 Z:E) and 14b, which were obtained in 6% and 5% yields, respectively. However, no β-lactam was obtained from this particular reaction. Due to the poor yields, we opted not to study this cyclopropanone further.

Scheme 9.

It appears that a bifurcation between two poorly productive mechanistic pathways occurs in these examples (Scheme 10). Thus, Schmidt ring-expansion chemistry leading to β-lactam 12, as well as ring-opening processes leading to constitutionally isomeric 1,2,3-oxaborazoles 13, 14a, and 14b were noted. The observation of two regioisomeric 1,2,3-oxaborazoles obtained from the reaction of 11 and phenylethyl azide can be ascribed to the non-specific formation of boron enolate diazo cation intermediates, each having a proton adjacent to the N-N bond. As before, triazinone involvement is possible here but not necessary (and not depicted in Scheme 10).

Scheme 10.

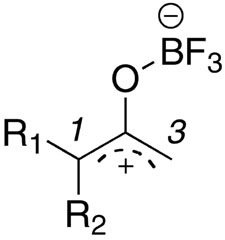

Discussion

Five chemotypes of products were observed from the Lewis acid-promoted reactions of azides with cyclopropanones (β-lactams, carbamates, α-amino-α′-diazomethylketones, 3-azetidinones, and [1,2,3]oxaborazoles). The first two of these were only observed in reasonable yields when cyclopropanone itself was used as the ketone substrate. This observation is most likely a consequence of more facile ring-opening of the latter compounds to afford alkyl- or aryl-stabilized oxyallyl cations.

The determination of whether the oxyallyl cation affords α-amino-α′-diazomethylketones, or 1,2,3-oxaborazoles depends on whether there is a proton α to the ketone and the regiochemistry of azide addition to the oxyallyl cation. Consider the example of 2,2-dimethylcyclopropanone, which affords α-amino-α′-diazomethyl ketones 4 along with small amounts of 3-azetidinones 5 (Scheme 11). The dimethyl-substituted oxyallyl cation is able to undergo attack by azide to afford two sets of regioisomeric products. One set consists of azide addition product A along with the analogous product of concerted [3+3] addition B; note that exclusive attack of electrophiles on the proximal nitrogen of the azide is well-precedented and also supported by theory (see below). The alternative regioisomeric products A′ and B′ are also possible, in principle. In this set of reactions, the formation of the observed products 4 and 5 require the intermediacy of B, which can break down as indicated in Scheme 4. However, note that the alternative regioisomer B′ cannot afford an isomeric α-amino-α′-diazomethylketone because doing so would require the cleavage of a C–C bond (there is no proton α to the ketone). Furthermore, either A′ or B′ could lead to an alternative 1,2,3-oxazaboroline product as shown at the bottom of the scheme. Thus, a key factor that determines the product profile in this reaction is the apparently exclusive formation or preferred reaction of regioisomers A/B in lieu of A′ or B′.

Scheme 11.

The aryl or alkyl monosubstituted examples could in principle lead to any of the observed products because of the presence of at least one proton at either side of the ketone (Scheme 12). However, the lack of any α-amino-α′-diazomethylketone products analogous to 5 suggests that this pathway is intrinsically less favorable than the alternative loss of a proton and formation of 1,2,3-oxazaboroline. For the observed products 9, 13, or 14, the intermediacy of a 1,2,3-triazin-5-one intermediate (B in Scheme 7) is permitted but not required. Indeed, it is not possible to settle on either pathway at the present.

Scheme 12.

Taken together, these results suggested that we address the source of the apparent regiochemical differences between cyclopropanones bearing 2,2-dimethyl vs. 2-aryl vs. 2-alkyl substitution. To this end, we carried out preliminary ab initio calculations to determine whether the regiochemical trends might be understood on the basis of frontier orbital considerations.26,27 Thus, B3LYP/6-31+G(d) calculations were performed on the three oxyallyl cations shown in Figure 2 and methyl azide (Figure 3).28 For a, the structure shown in Figure 2 was the only conformer that could be located at this level of theory. At the RHF/6-31G(d) level of theory, a second conformer had been located, while no conformers could be found at the MP2/6-31G(d) level of theory. For b, only one conformer could be located at all levels of theory. This could mean that dimethyl and phenyl substituted analogues a and c are more stable than the methyl oxyallyl cation b. Three conformers were found for oxyallyl cation c at all levels of theory. The lowest energy conformer for the phenyl substituted oxyallyl cation c is depicted in Figure 2. All structures were confirmed to be ground state structures via frequency calculations. For a particular molecular orbital, the coefficients for each atom were calculated by summing the squares of the coefficients for each basis set orbital on that atom.

Figure 2.

Low energy conformations used for the calculation of oxyallyl LUMO coefficients.

Figure 3.

B3LYP/6-31+G* molecular orbital coefficients for the HOMOs of methyl azide.

In all cases, the energy gap between the HOMO of the methyl azide and the LUMO of the oxyallyl cation was much smaller than the energy gap between the LUMO of the methyl azide and the HOMO of the oxyallyl cation.29 The coefficients of the HOMO of methyl azide and the LUMO of the oxyallyl cation, reported in Table 5 suggest that both orbitals are similar to the allyl nonbonding orbital.30 For methyl azide, the proximal nitrogen has a larger coefficient than the distal nitrogen (Figure 3).31 It is likely that the same regioisomeric preferences would be observed regardless of stepwise nucleophilic attack of azide upon oxyallyl cation or in a HOMOazide–LUMOoxyallyl cation controlled [3+3] concerted reaction.

Table 5.

B3LYP/6-31+G* molecular orbital coefficients for the LUMOs of oxyallyl cations

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUMO coefficients

|

|||||

| entry | oxyallyl cation | R1 | R2 | C(1) | C(3) |

| 1 | a | CH3 | CH3 | 0.51 | 0.23 |

| 2 | b | CH3 | H | 0.38 | 0.30 |

| 3 | c | C6H5 | H | 0.26 | 0.23 |

The calculated azideHOMO-oxyallylLUMO coefficients for oxyallyl cation a are in line with the results obtained with this substrate: α-amino-α′-diazomethyl ketones, which result from proximal azide attack at C1, were exclusively observed. The small difference in the calculated LUMO cofficients at C1 and C3 for oxyallyl cation b are likewise consistent with non-specific formation of a mixture of constitutionally isomeric 1,2,3-oxaborazoles 13 and 14. Furthermore, the apparent lack of stability of the oxyallyl cation b may be reflected in the poor efficiency of these reactions. This same effect could also contribute to the small amount of 3-azetidone 12 observed by making the ring opening to the oxyallyl cation less favorable in comparison to ketone addition.

The most difficult case to understand is that of the oxyallyl cation c derived from phenylcyclopropane. This species has comparable LUMO coefficients at C1 and C3, yet a single 1,2,3-oxaborazole consistent with proximal bond formation of the azide onto the oxyallyl cation at C-3 was formed in its reactions with alkyl azides. There are several possible explanation for this. Since the LUMO coefficients at C1 and C3 are of comparable magnitude, a simple steric bias may override any small electronic preference for attack at C1. On the other hand, it is possible that the initial addition reaction or even the [3+3] reaction is reversible and that the elimination of a proton Hb from intermediate A′ is favored over the alternative loss of Ha (Scheme 7). However, the present studies do not address how likely this possibility is. The presence of the phenyl group could also stabilize the oxyallyl cation and contribute to the reversibility of the initial reaction.

Summary

The Lewis acid-mediated reactions of cyclopropanones with alkyl azides provide access to a variety of distinct products. Marked differences in reaction course and regiochemistry were encountered depending on the substitution pattern of the starting cyclopropanone acetal. We believe that the products obtained from the reactions described in this paper are the result of divergent reaction pathways (1) exploiting the “traditional” ketone behavior for unsubstituted cyclopropanone, providing 2-azetidinone and carbamates and (2), the oxyallyl cationic behavior of substituted cyclopropanones. In these cases, the nature of the oxyallyl cation appears to affect the regiochemistry of azide addition and whether the products are α-amino-α′-diazomethyl ketones or 1,2,3-oxaborazoles. The regiochemistry of azide addition appears to be in accordance with simple FMO theory, although that method does not fully address the situation with the phenyl case. To that end, future studies will include a full ab initio study of the various pathways in hopes of understanding the mechanisms of this suite of reactions and how they are modulated by substitution.

Experimental Section

General procedure for the preparation of β-lactam and ethyl carbamate Products

To a solution of alkyl azide (2.0 equiv) in 8 mL of CH2Cl2 at 0 °C was added [(1-ethoxycyclopropyl)oxy]trimethylsilane (1.0 equiv). The mixture was stirred for 10 min and BF3•OEt2 (2.5 equiv) was added dropwise; gas evolution was observed. The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 20 h at which time 10 mL saturated NaHCO3 and 10 mL CH2Cl2 were added. The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (4 × 10 mL), and the combined organic layers were washed with brine and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. Concentration followed by chromatography (20% EtOAc/hex) afforded the β-lactam and ethyl carbamate products.

|

N-Phenylmethyl azetidin-2-one (2a)

Clear oil (45%). Known compound.32

|

N-Phenylmethylcarbamic acid ethyl ester (3a)

Clear oil (13%). Known compound.33

General procedure for the reaction of triethyl-(1-methoxy-2,2-dimethyl-cyclopropoxy)-silane with alkyl azides

Triethyl-(1-methoxy-2,2-dimethyl-cyclopropoxy)silane (1.0 equiv) was added to a solution of alkyl azide (2.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL). The reaction mixture was cooled to −78 °C and BF3•OEt2 (1.0 equiv) was added dropwise. The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred overnight, at which time it was poured into saturated NaHCO3 (10 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 10 mL). The organic layer was then dried with MgSO4 and evaporated to provide a residue, which was purified by flash chromatography (20% EtOAc/hex).

|

1-Diazo-3-methyl-3-phenylaminobutan-2-one (5a)

Yellow oil (47%): Rf = 0.06 (20% EtOAc/hex); IR (neat) 3326, 2099, 1633 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ7.37-7.26 (m, 5H), 5.96 (br s, 1H), 3.66 (s, 2H), 1.60 (br s, 1H), 1.34 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 201.3, 140.7, 128.9, 128.4, 127.5, 62.6, 52.2, 48.6, 25.8; CIMS m/z (relative intensity) 218 (MH+, 100), 190 (97); HRMS calcd for C12H16N3O: 218.1293, found: 218.1268.

|

1-Benzyl-2,2-dimethyl-azetidin-3-one (6a)

Yellow oil (4%): Rf = 0.14 (20% ethyl acetate/hexanes); IR (neat) 2970, 1804 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ7.25–7.39 (m, 5H), 4.03 (s, 2H), 3.84 (s, 2H), 1.30 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 209.1, 139.3, 128.8, 128.7, 127.5, 83.8, 71.0, 55.4, 20.3; CIMS m/z (relative intensity) 190 (MH+, 76), 160(11), 148(23), 91 (100), 70 (81); HRMS calcd for C12H16NO 190.1232, found 190.1221.

General procedure for the reaction of aryl- and monalkyl-substituted cylopropanone silyl acetals with alkyl azides

To a solution of cyclopropanone acetal (1.0 equiv) and alkyl azide (2.0 equiv), was added BF3•OEt2 (2.0 equiv). The reaction vial was immediately sealed and placed in a microwave and heated at 135° C for 10 minutes. The reaction mixture was then diluted in CH2Cl2 15 (mL) and washed with a saturated solution of NaHCO3 (50 mL). The mixture was extracted twice with CH2Cl2 (25mL). The combined extracts were then dried with MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. The remaining residue was then purified by column chromatography using 5–20% EtOAc/hexanes as eluent.

|

3-Benzyl-5-benzylidene-2,2-difluoro-2,5-dihydro-[1,2,3]oxaborazole (9a)

White solid (51 mg, 50%). Rf = 0.13 (20% EtOAc/hex); mp 153–156 °C; IR (KBr pellet) 3450, 1644, 1629 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3 δ 7.88 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.59 (br s, 1H), 7.41 (m, 8H), 5.98 (s, 1H), 4.86 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 163.8, 149.1, 133.6, 132.3, 130.6, 129.7, 129.5, 129.4, 129.3, 128.7, 128.6, 119.0, 52.0; MS (FAB) m/z 285 (M+), 266; HRMS calcd for C16H14BF2NO: 285.1137, found 285.1136.

General procedure for the Rh2(OAc)2-catalyzed cyclization of α-amino-α′-diazomethylketones

Compounds 2 (0.138 mmol) in 2 mL of CH2Cl2 were added to a solution of Rh2(OAc)4 (3 mg, 0.007 mmol) in 2 mL of CH2Cl2 at 0 °C. The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 20 h at which time 10 mL of water was added. The aqueous layer was partitioned between CH2Cl2 and brine and dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and evaporated to provide a yellow oil, which was purified by flash chromatography (20% EtOAc/hex).

|

1-Benzyl-2,2-dimethyl-azetidin-3-one (6a)

Yellow oil (90%): Rf = 0.14 (20% ethyl acetate/hexanes); IR (neat) 2970, 1804 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ7.25–7.39 (m, 5H), 4.03 (s, 2H), 3.84 (s, 2H), 1.30 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 209.1, 139.3, 128.8, 128.7, 127.5, 83.8, 71.0, 55.4, 20.3; CIMS m/z (relative intensity) 190 (MH+, 76), 160(11), 148(23), 91 (100), 70 (81); HRMS calcd for C12H16NO 190.1232, found 190.1221.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedure for the preparation of substituted cyclopropanone acetals, and acidic ethanolysis of 9a, characterization data for compounds 2b–4, 5b–8, 9b–14b, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra for compounds 2b, 2c, 2d–9g, 12–14b; CIF for compound 9g; and details of calculations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health for financial support via GM-49093. S.G. gratefully acknowledges receipt of a Madison and Lila Self Graduate Fellowship.

References

- 1.(a) Turro NJ. Acc Chem Res. 1969;2:25–23. [Google Scholar]; (b) Turro NJ, Gagosian RB, Edelson SE, Darling TR, Williams JR, Hammond WB. T New York Acad Sci. 1971;33:396–404. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wasserman HH, Clark GM, Turley PC. Top Curr Chem. 1974;47:73–156. [Google Scholar]; (d) Salaun J. Chem Rev. 1983;83:619–632. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Baretta A, Waegell B. In: Reactive Intermediates. Abromovich RA, editor. Vol. 2. New York: 1982. pp. 527–585. [Google Scholar]; (b) Moulay S. Chemistry Education: Research and Practice in Europe. 2002;3:33–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Turro NJ, Edelson SS, Williams JR, Darling TR, Hammond WB. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:2283–2292. [Google Scholar]; (b) Liberles A, Greenberg A, Lesk A. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:8685–8688. [Google Scholar]; (c) Zandler ME, Choc CE, Johnson CK. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:3317–3319. [Google Scholar]; (d) Turecek F, Drinkwater DE, McLafferty FW. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5950–5958. [Google Scholar]; (e) Hess BA, Jr, Eckart U, Fabian J. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12310–12315. [Google Scholar]; (f) Hess BA, Jr, Smentek L. Eur J Org Chem. 1999:3363–3367. [Google Scholar]; (g) Lim D, Hrovat DA, Borden WT, Jorgensen WL. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:3494–3499. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) McElvain SM, Weyna PL. J Am Chem Soc. 1959;81:2579–2588. [Google Scholar]; Dull MF, Abend PG. J Am Chem Soc. 1959;81:2588–2591. [Google Scholar]; (b) Giusti G, Morales C. Bull Soc Chim France. 1973:382–387. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rousseau G, Slougui N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:1251–1254. [Google Scholar]; (d) Salaun J, Marguerite J. Org Synth Coll. 1989;VII:131–134. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Wasserman HH, Clagett DC. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:5368–5369. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wasserman HH, Cochoy RE, Baird MS. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:2375–2376. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wasserman HH, Baird MS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971:3721–3724. [Google Scholar]; (d) Van Tilborg WJM, Steinberg H, De Boer TJ. Synth Commun. 1973;3:189–196. [Google Scholar]; (e) Wasserman HH, Glazer E. J Org Chem. 1975;40:1505–1506. doi: 10.1021/jo00898a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turro NJ, Hammond WB. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:6017–6028. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Turro NJ, Hammond WB. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:1028–1029. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bakker BH, van Ramesdonk HJ, Steinberg H, de Boer TJ. RTCPB. 1975;94:64–69. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hess BA, Jr, Eckart U, Fabian J. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12310–12315. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cho SY, Lee HI, Cha JK. Org Lett. 2001;3:2891–2893. doi: 10.1021/ol016354s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Wasserman HH, Adickes HW, Espejo de Ochoa O. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:5586–5587. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wasserman HH, Baird MS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971:3721–3724. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wasserman HH, Glazer EA, Hearn MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973:4855–4858. [Google Scholar]; (d) Wasserman HH, Glazer E. J Org Chem. 1975;40:1505–1506. doi: 10.1021/jo00898a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Aubé J, Milligan GL. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:8965–8966. [Google Scholar]; (b) Aubé J, Milligan GL, Mossman CJ. J Org Chem. 1992;57:1635–1637. [Google Scholar]; (c) Aubé J, Rafferty PS, Milligan GL. Heterocycles. 1993;35:1141–1147. [Google Scholar]; (d) Milligan GL, Mossman CJ, Aubé J. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:10449–10459. [Google Scholar]; (e) Mossman CJ, Aubé J. Tet. 1995;52:3403–3408. [Google Scholar]; (f) Gracias V, Frank KE, Milligan GL, Aubé J. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:16241–16252. [Google Scholar]; (g) Forsee JE, Smith BT, Frank KE, Aubé J. Synlett. 1998:1258–1260. [Google Scholar]; (h) Schildknegt K, Agrios KA, Aubé J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:7687–7690. [Google Scholar]; (i) Desai P, Aubé J. Org Lett. 2000;2:1657–1659. doi: 10.1021/ol0056628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Desai P, Schildknegt K, Agrios KA, Mossman C, Milligan GL, Aubé J. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7226–7232. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai P, Aubé J. Org Lett. 2000;2:1657–1659. doi: 10.1021/ol0056628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Olah GA, Kelly DP, Jeuell CL, Porter RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:2544–2546. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mayr H, Olah GA. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:510–513. [Google Scholar]; (c) Olah GA, Liang G, Ledlie DB, Costopoulos MG. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:4196–4198. [Google Scholar]; (d) Olah GA, Reddy VP, Prakash GKS. Chem Rev. 1992;92:69–95. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Pirrung MC. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:7207–7209. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pirrung MC. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:711–718. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katritzky AR, Cundy DJ, Chen J. J Heterocycl Chem. 1994;31:271–275. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakker BH, van Ramesdonk HJ, Steinberg H, de Boer TJ. RTCPB. 1975;94:64–69. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Deno NC, Jaruzelski JJ, Schriesheim A. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:3044–3051. [Google Scholar]; (b) Arnett EM, Hofelich TC. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:2889–2895. [Google Scholar]

- 16.For an outstanding recent review of alkyl azide chemistry, see Bräse S, Gil C, Knepper K, Zimmermann V. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:5188–5240. doi: 10.1002/anie.200400657.

- 17.Attack of nucleophiles at the terminal end of an azide, i.e., as seen in the Staudinger reaction, is known: Nyffeler PT, Liang CH, Koeller KM, Wong CH. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10773–10778. doi: 10.1021/ja0264605. and references cited therein.

- 18.Sakurai H, Shirahata A, Hosomi A. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1979;91:178–179. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Pearson WH, Fang W-k, Kampf JW. J Org Chem. 1994;59:2682–2684. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schultz AG, Myong SO, Puig S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:1011–1014. [Google Scholar]; (c) Schultz AG, Macielag M, Plummer M. J Org Chem. 1988;53:391–395. [Google Scholar]; (d) Rostami A, Wang Y, Arif AM, McDonald R, West FG. Org Lett. 2007;9:703–706. doi: 10.1021/ol070053m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Regitz M, Maas G. Diazo Compounds: Properties and Synthesis. Academic; Orlando: 1986. p. 596. [Google Scholar]; (b) Baumann H, Duthaler RO. Helv Chim Acta. 1988;71:1035–1041. [Google Scholar]; (c) Podlech J, Seebach D. Helv Chim Acta. 1995;78:1238–1246. [Google Scholar]; (d) Axenrod T, Watnick C, Yazdekhasti H, Dave PR. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1959–1964. doi: 10.1021/jo9614755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rousseau G, Slougui N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:1251–1254. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) White DL, Faller JW. Inorg Chem. 1982;21:3119–3122. [Google Scholar]; (b) Joseph-Nathan P, Garibay ME, Santillan RL. J Org Chem. 1987;52:759–763. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yuan G, Jiang M, Zhang G. Wuji Huaxue Xuebao. 1990;6:314–318. [Google Scholar]; (d) Joseph-Nathan P, Burgueno-Tapia E, Santillan RL. J Nat Prod. 1993;56:1758–1765. [Google Scholar]; (f) Patel BP. US Patent 5348948. 1994; (g) Agustin D, Rima G, Gornitzka H, Barrau J. Organometallics. 2000;19:4276–4282. [Google Scholar]; (h) Hopfl H, Barba V, Vargas G, Farfan N, Santillan R, Castillo D. Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds. Vol. 35. New York: 2000. pp. 912–927. [Google Scholar]; (i) Ramos J, Soderquist JA. ARKIVOC. 2001:43–58. [Google Scholar]; (j) Tavassoli A, Benkovic SJ. WO Patent 2003059916. 2003

- 23.(a) Chow YL, Cheng X. Chem Commun. 1990:1043–1045. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chow YL, Cheng X. Can J Chem. 1991;69:1575–1583. [Google Scholar]; (c) Cogne-Laage E, Allemand JF, Ruel O, Baudin JB, Croquette V, Blanchard-Desce M, Jullien L. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:1445–1455. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Kingston HM, Haswell SJ, editors. Microwave-Enhanced Chemistry: Fundamentals, Sample Preparation, and Applications. American Chemical Society; Washington D. C.: 1997. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lidstrom P, Tierney J, Wathey B, Westman J. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:9225–9283. [Google Scholar]; (c) Loupy A. Microwaves in Organic Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Xiong H, Huang J, Ghosh SK, Hsung RP. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12694–12695. doi: 10.1021/ja030416n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rameshkumar C, Hsung RP. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:615–618. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walters MA, Arcand HR. J Org Chem. 1996;61:1478–1486. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frisch MJ, GWT, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Zakrzewski VG, Montgomery JA, Jr, Stratmann RE, Burant JC, Dapprich S, Millam JM, Daniels AD, Kudin KN, Strain MC, Farkas O, Tomasi J, Barone V, Cossi M, Cammi R, Mennucci B, Pomelli C, Adamo C, Clifford S, Ochterski J, Petersson GA, Ayala PY, Cui Q, Morokuma K, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Cioslowski J, Ortiz JV, Baboul AG, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Gomperts R, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Andres JL, Gonzalez C, Head-Gordon M, Replogle ES, Pople JA. Gaussian 98 RevisionA. 11. Gaussian, Inc.; Pittsburgh: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cramer CJ, Barrows SE. J Phys Org Chem. 2000;13:176–186. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noyori R, Shimizu F, Fukuta K, Takaya H, Hayakawa Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:5196–5198. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inclusion of solvent (dichloromethane) via the IEFPCM algorithm in Gaussian03 gave a similar trend with the differences in coefficients being 0.12 for methyl azide, 0.08 for a, 0.21 for b and 0.07 for c.

- 31.Houk KN, Sims J, Duke RE, Jr, Strozier RW, George JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:7287–7301. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holley RW, Holley AD. J Am Chem Soc. 1949;71:2124–2129. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reimer M. J Am Chem Soc. 1926;48:2454–2462. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedure for the preparation of substituted cyclopropanone acetals, and acidic ethanolysis of 9a, characterization data for compounds 2b–4, 5b–8, 9b–14b, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra for compounds 2b, 2c, 2d–9g, 12–14b; CIF for compound 9g; and details of calculations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.