Abstract

Microarrays provide a means of studying expression level of tens of thousands of genes by providing one or more oligonucleotide probe(s) for each transcript studied. Affymetrix® GeneChip™ platforms historically pair each 25-base perfect match (PM) probe with a mismatch probe (MM) differing by a complementary base located in the 13th position to quantify and deflate effects of cross-hybridization. Analytical routines for analyzing these arrays take into account difference in expression levels of MM and PM probes to determine which ones are useful for further study. If a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) occurs at the 13th base, a probe with a higher MM expression level may be incorrectly omitted. In order to examine SNP affects on PM and MM expression levels, known human SNPs from dbSNP were mapped to probe sets within the Affymetrix® HG-U133A platform. Probe sets containing one or more probe pairs with a single SNP at the 13th position were extracted. A set of twelve microarray experiments were analyzed for the PM and MM expression levels for these probe sets. Over 6,000,000 human SNPs and their flanking regions were extracted from dbSNP. These sequences were aligned against each of the 247,965 probe pair sequences from the Affymetrix® HG-U133A platform. A total of 915 probe sets containing a single probe sequence with a SNP mapped to the 13th base were extracted. A subset containing 166 probe sets result in complementary base SNPs. Comparison of gene expression levels for the SNP to non-SNP PM and MM probes does not yield a significant difference using χ2 analysis. Thus, omission of probes with MM expression levels higher than PM expression levels does not appear to result in a loss of information concerning SNPs for these regions.

Keywords: Affymetrix HG-U133A, single nucleotide polymorphism, microarray, probe, mismatch

Background

Microarray technology

Technological breakthroughs within the past couple of decades have changed the face of molecular biology by allowing researchers to generate large volumes of biologically relevant data in a short period of time. These advances have led to the “omics” era of research [1] marked by genomics (study of genomes), proteomics (study of protein expression), cellomics (study of the cell), and transcriptomics (study of transcribed regions). Transcriptomics has been aided by the invention of the microarray [2] which allows researchers to study patterns of gene expression across tens of thousands of genes simultaneously. Major companies providing commercial solutions include Affymetrix®, Agilent®, and CodeLink®. Each of these approaches provides one or more short oligonucleotide probe(s) sequence complementary to the product of the transcript of interest.

The Affymetrix® oligonucleotide platforms are constructed to allow multiple oligonucleotide probes per probe set, where each probe set represents a single gene or transcript. For the HU-133A platform for studying human transcripts, there are over 22,000 different probe sets represented, with each non-control probe set containing 11 25-base oligonucleotide sequence probes [3]. In order to help quantify and control the effects of cross-hybridization, the Affymetrix® approach groups probes into pairs consisting of a perfect match probe (PM) and a mismatch probe (MM). The perfect match probe is a 25 base oligonucleotide complementary to the transcript and the mismatch probe is the same as the PM with the exception that the 13th base is complementary to the corresponding position in the PM set. For example, one of the eleven probe pairs for the 206055_s_at probe set is as follows: PM GCACAGCTTGCAAAGGATATTGCCA MM GCACAGCTTGCATAGGATATTGCCA

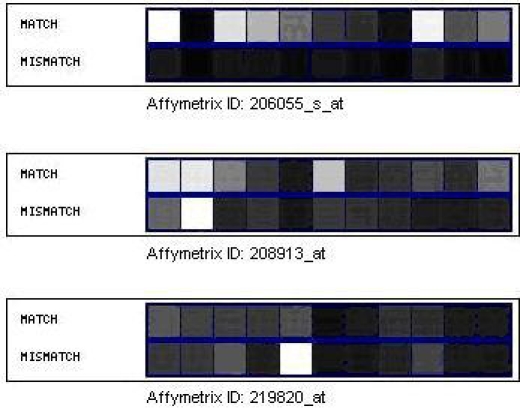

Figure 1 shows an example of the expression levels of the MM and PM probes for three Affymetrix® probe sets found within the HU-133A platform.

Figure 1.

Affymetrix probe set pair expression levels. Shown are the expression levels for three separate Affymetrix probe sets represented on a 0-255 color scale. Each probe set contains eleven probe pairs, with each pair represented by a match and mismatch sequence.

Since mismatch data allows for detection of cross-hybridization, a probe set could be selected for inclusion or exclusion based on the corresponding match/mismatch values. For the probe set 206055_s_at in Figure 1, each of the probe pairs could be used since the expression values of the match is consistently higher than the value of the corresponding mismatch probe located directly below. However, for probe set 219820_at in Figure 1, the fifth match/mismatch pair from the left is potentially excluded since the mismatch expression value is much greater than the match expression value. This probe pair would be excluded since the resulting differences in expression level is thought to be due to cross hybridization.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, often pronounced as snips) are single nucleotide base differences in a specific position of genomic DNA among two different individuals of the same species. SNPs are the most common form of genetic variation that helps to differentiate individuals in a population. A number of diseases and abnormalities, including sickle cell anemia [4], cystic fibrosis [5], muscular dystrophy [6], type II diabetes [7], and migraine headaches [8] are influenced by the presence of SNPs occurring within gene coding regions.

The rate of occurrence of SNPs in the human genome is around one every 100 to 300 base pairs. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) maintains a publicly available database of annotated human SNPs, known as dbSNP [9]. The current build of dbSNP (build 127) contains nearly 12 million annotated human SNPs.

While SNPs are important in disease association studies, their presence becomes problematic for genome wide analysis. As an example, one of the difficulties with the Affymetrix® microarray platforms is that each of the chips are designed to be representative for all individuals within an organism-level classification. However, with the high frequency of SNPs, it is possible that a SNP locus is found within a particular probe sequence. This becomes especially problematic if the locus corresponds to the 13th base pair, and the SNP variant is the complementary base. Such a case would result in a higher hybridization rate for the mismatch probe as opposed to the match probe.

The independent and dependent effect of both SNPs and copy number variants (CNVs) on gene expression has been known to be an issue when studying microarrays [10]. The development of SNP chips [11] has made it possible to genotype SNPs and has led to the real possibility of Whole Genome Association Studies (WGAS). However, a large number of gene expression studies using microarray probe technology exist that might label certain probes for exclusion due to higher MM hybridization rates that is actually due to the presence of complementary SNPs.

In order to test for the effect of SNPs on probe hybridization, we looked at all 247,965 match probes within the Affymetrix® HU-133A platform and compared them against dbSNP to see which probes contained SNP loci within them. For those where the sole SNP loci was found at the 13th base, we compared the expression levels of the PM probe to the MM probe for each of the probes within the probe set. We specifically wanted to see if the MM probe with the SNP at the 13th base varied more than those probes that did not contain any SNP loci.

Methodology

Data acquisition

For the purposes of this study, three key data components were required: human genomic data, human SNP data, and probe sequence data. Human genomic sequence was obtained from the University of California-Santa Cruz’s goldenpath web site (http://goldenpath.ucsc.edu) [12,13] for the hg17 build of the human genome. The resulting data was contained in 27 files. Human SNPs were downloaded from build 124 of the dbSNP database [14] maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). This data is itself based on build 33 of the NCBI Human genome. Probe sequence data representing the 247,965 twenty-five base perfect match oligomers from the HG-U133A microarray manufactured by Affymetrix® were downloaded from the netaffx utility on the Affymetrix® web site http://www.affymetrix.com/.

Expression levels of probe sequences containing SNPs were compared within a set of twelve samples for the GEO [15] record GDS1758. This dataset originates from a study on the developmental pathway involved in pterygium, an ocular surface disorder within a sample set of Chinese patients [16]. Rather than focus on a large dataset with a mixture of patients from different ethnicities, this smaller dataset was chosen from a single ethnic group so that ethnic specific major and minor allele frequencies could be determined. The individual CEL files used are labeled GSM48026.CEL, GSM48027.CEL, GSM48028.CEL, GSM48029.CEL, GSM48030.CEL, GSM48031.CEL, GSM48032.CEL, GSM48033.CEL, GSM48034.CEL, GSM48035.CEL, GSM48036.CEL, and GSM48037.CEL.

Preprocessing

Perfect match probe sequences for the HG-U133A platform were stored in a tab-delimited format with information concerning the probe set name, probe x position, probe y position, interrogation position, probe sequence, and strandedness (Table 1 under supplementary material). The resulting tab-delimited files were parsed using perl scripts to reconstruct sequence files in FASTA format for sequence comparison.

Sequences originating from the dbSNP database each represent a single instance of a known SNP denoted by the standard IUPAC-IUB code [17]. dbSNP sequences typically range from a few hundred to a few thousand bases in length. For the purpose of our study we were only interested in the sequence immediately surrounding the SNP for alignment with the twenty-five base oligomer sequence from the HG-U133A microarray. A perl script was created to extract a forty-nine base segment from each dbSNP sequence, spanning twenty-four bases upstream and downstream of the SNP location, when available. In some cases, the allele position or length of the original sequence did not allow for all of the bases to be extracted.

The original downloaded dbSNP sequences were soft-masked for low-complexity regions and tandem repeats. While this can be beneficial in order to remove regions of low significance and to avoid spurious sequence hits, our study required us to unmask the source data in order to produce exact alignments with microarray probe sequences. Sequences were thus restored to their original format for sequence alignment purposes. The resulting unmasked data was verified by comparison between the original and truncated data.

Sequence alignment

Alignments between the microarray oligomer probes and the dbSNP sequences were performed using the nucleotide-nucleotide comparison tool wublastn from the WU-BLAST 2.0 suite of programs [18,19]. The dbSNP database was formatted into a BLASTable database using the xdformat utility, leaving the microarray probes as the query sequences. Since the sequences were expected to be exact matches with the exception of any SNPs present, ungapped alignments were performed. This has the additional benefit of decreasing search time. A word size of eight was used to allow for alignments with up to two mismatches within a 25 base alignment. A score cutoff of 95 was used to allow for a combination of two mismatches/gaps within a 25 base alignment using a scoring scheme of +5/−4 for matches and −10 for gap open penalty. The remaining parameters were set at the default values. In summary, the blast command line was as follows: blastn <database> <query> -nogaps −S=95 −W=8. To further maintain the focus of the project, the parameterized wublastn results were filtered through a Perl script to only store those alignments that were at least 22 bases in length.

Parsing and storing the results

The wublastn searches were conducted chromosome-wise, keeping the structure of the source data intact. wublastn output was piped through Perl scripts to filter out the basic statistical information required for a database table. A Perl script incorporating BPlite [20] was used to further parse the output to store alignments of 22 or more bases with the following information stored in plain text files are as follows:

Reference numbers of the query and target sequences.

Sequence locations on the microarray and on the dbSNP and genomic databases.

Location of the SNP within a dbSNP segment.

Lengths of the query and target sequences.

Start and end positions of the alignments found.

Aligned segment pairs.

Alignment string itself, which is a means of depicting the matched and mismatched base pairs within a sequence. Matching pairs have a ‘|’ between them, mismatches remain blank and where a base in the query sequence matches any one of the possible variations of the SNP, a plus sign (‘+’) is used to show this ‘partial’ match.

Length of the alignment found.

Number of matches within the sequence.

Percent identity of the matches (number of matches divided by the alignment length).

Raw score of the alignment from the standard scoring scheme of wublastn.

A MySQL database was created to store the parsed results. The database schema consists of six tables. One of these tables captures the database information, and a second is used for the organism records. The remaining four tables captured alignment data: one to hold the identification for the microarray probes; a second to hold the identification information for the segments from the dbSNP files; a third to store the alignment data such as the source and target alignment strings; and the fourth to store the statistical data corresponding to the alignments. A shared key field was generated for each of the tables using the chromosome and alignment number.

Discussion

SNP and probe alignments

Over six million ungapped alignments were found between microarray probes and SNP segments. These resulted in a total of 45,984 perfect match sequences between the probes and SNP segments. An additional of 1,656 probe sequence alignments result in a mismatch nucleotide in the 13th base. Further filtering yields 915 alignments where the probe sequence contains only a single SNP, and that probe is the only one within its corresponding probe group to contain any known SNPs. Of these 915, a subset of 166 results in a complementary base mismatch. Bearing in mind that Affymetrix® microarrays have pairs of probes where one half of the pair has the complement of the other's 13th base, these probes were marked for further analysis. A total of 58,505 sequences with a single mismatch were detected, but not included in our analysis.

The 166 alignments resulting in a single, complementary base mismatch originate from unique probe sets. Those probe pairs containing a region where a SNP is present have the potential to have higher expression level in the mismatch probe than in the match probe depending upon the individual's genotype. In order to test if this was the case, each of the eleven probe pairs within each corresponding probe sets were compared to see how frequently the match expression level was greater than the mismatch expression both in those probe pairs without a SNP and those probe pairs where a SNP is mapped to the 13th position. Expression data was obtained using CEL files for 12 different experiments as discussed in the Methodology section. The resulting data set yields 1670 non-SNP containing probes, and 166 SNP containing probes. For the complete set of 1836 probes, the number of times that the mismatch expression data was higher than the match expression data was reported. Table 2 (see supplementary material) is constructed from this dataset, noting the number of times that the mismatch probe expression level is observed to be greater than the match probe expression level.

Analysis

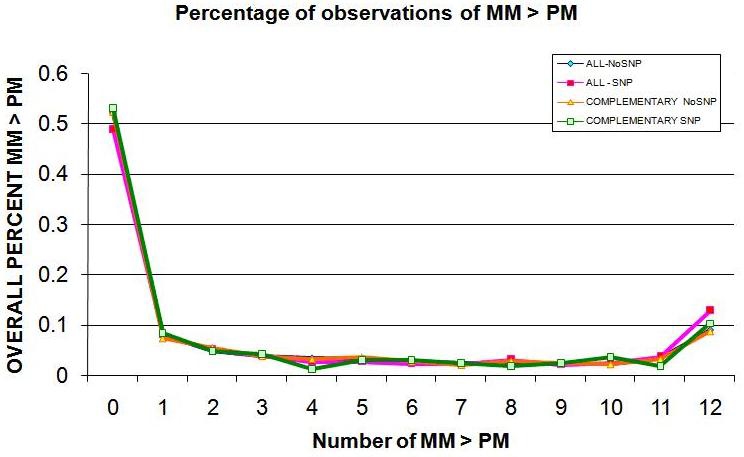

Table 2 (see supplementary material) indicates the number of times the MM probe is greater than the PM probe occurs with less frequency in the probes with a SNP in the 13th base than it does in probes without SNPs, debunking our hypothesis. It is observed that about 52% of the time in probes without SNPs, the perfect match probe expression level is always greater than the mismatch probe expression level, while this occurs at approximately the same rate in probes with a SNP in the 13th base. One interesting piece of information is that the mismatch probe expression level is always greater than the match expression level in both instances around 9% of the time. A graph of the frequency of these events is shown in Figure 2. The number of observations from the SNP and nonSNP data was compared using χ2 analysis. The resulting χ2 value of 6.0108 with 12 degrees of freedom has a p-value of 0.9155, thus rejecting the alternative hypothesis that the SNP and nonSNP data are significantly different.

Minor allele frequencies

The 166 unique complementary SNPs have been mapped according to known SNPs from the dbSNP database which contains SNPs for all population types. However, since the experiments selected are focused on the HapMap Han Chinese in Beijing (HCB) population, it is possible the observed results are skewed according to population-specific SNPs. Each of the 166 dbSNP references were searched against HapMap using HapMart release 23a. Sixty-four of the 166 SNP containing probes have been genotyped for the HCB group by the HapMap project, each with between 72 and 90 allelic observations. However, only 20 of these have a minor allele frequency of 5% or greater (Table 3 in supplementary material). The SNP to nonSNP probe groups for this set of 20 SNPs were compared as previously discussed. A comparison of the number of times the MM probes was greater than the PM probes is given in Table 4 (shown under supplementary material) for these 20 SNPs. Since the number of observations is low, Fisher's exact test was performed on the SNP to nonSNP group, resulting in a p-value of 0.04113. The p-value is much lower than before, and indicates a significant difference in the distributions when a p-value threshold of 0.05 is considered. This indicates that perhaps with more observations, it could be possible to differentiate between differences in MM and PM arising due to allelic variations and those from cross hybridizations.

Conclusion

The recent publications of the complete diploid genome of two individual humans indicate that the rate of SNP variation within an individual is much larger than previously expected [21]. The higher rate of variation in the zygosity presents an issue when looking at gene expression. Our hypothesis states that we would expect to see higher hybridization rates for mismatch probes in regions where a SNP is found in the 13th base of a probe sequence. However, initial results on twelve microarray experiments illustrate this is not the case, and in fact, the opposite is true. Further analysis of the samples used, including genotyping information, would be useful in determining if these discrepancies result due to the frequency of certain haplotypes within a population.

When known haplotype frequencies are considered, it is still difficult to differentiate between true SNPs and cross hybridization although the distributions are more distinct. Part of this inability may be due to low number of SNPs (20) falling into this category. As more haplotype frequency information becomes available for all 166 candidate SNPs through the HapMap project, it may become plausible to differentiate between cross-hybridization. Additional haplotype information for the other HapMap populations may result in additional alleles with higher minor allele frequencies.

The ability to discern between cross-hybridization and infrequent SNPs based on PM and MM data is difficult at best. SNPs remain a tricky issue when microarray probe design is considered. It is our conclusion that information is not lost when these probes are discarded, since the source of the discrepancy cannot be consistently determined.

Supplementary material

Figure 2.

Percentage of observations of mismatch probe expression greater than perfect match probe expression.

Acknowledgments

Support for this project was provided by NIH-NCRR grant P20RR16481 and NIH-NIEHS grant P30ES014443. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and may not represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources, the National Institute for Environmental and Health Science, or the National Institutes of Health. ECR and AWP contributed equally to this project. The authors would like to thank the University of Louisville Bioinformatics Research Group (BRG) and the University of Louisville Bioinformatics Laboratory for numerous fruitful discussions.

References

- 1.Palsson B. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:649. doi: 10.1038/nbt0702-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schena M, et al. Science. 1995;270:467. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. http://www.affymetrix.com/

- 4.Chang JC, Kan YW. Lancet. 1981;2:1127. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90584-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mateu E, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:111. doi: 10.1086/316940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig M, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;45:498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vionnet N, et al. Nature. 1992;356:721. doi: 10.1038/356721a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wessman M, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;270:467. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherry ST, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stranger BE, et al. Science. 2007;315:848. doi: 10.1126/science.1136678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan JB, et al. Genome Res. 2000;10:853. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.6.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kent WJ, Haussler D. Genome Res. 2001;11:1541. doi: 10.1101/gr.183201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kent WJ, et al. Genome Res. 2002;12:996. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherry ST, et al. Genome Res. 1999;9:677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrett T, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D760. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong YW, et al. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:769. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.087486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IUPAC-IUB commission on biochemical nomenclature (CBN) J Mol Biol. 1971;55:299. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altschul SF, et al. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouchka EC. Conversation with: W. Gish. 2004.

- 20.Rouchka EC. Conversation with: I. Korf. 2004.

- 21.Levy S, et al. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.