Abstract

We have characterized the properties and putative role of a mammalian thioredoxin-like protein, ERp16 (previously designated ERp18, ERp19, or hTLP19). The predicted amino acid sequence of the 172-residue human protein contains an NH2-terminal signal peptide, a thioredoxin-like domain with an active site motif (CGAC), and a COOH-terminal endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention sequence (EDEL). Analyses indicated that the mature protein (comprising 146 residues) is generated by cleavage of the 26-residue signal peptide and is localized in the lumen of the ER. Biochemical experiments with the recombinant mature protein revealed it to be a thioldisulfide oxidoreductase. Its redox potential was about -165 mV; its active site cysteine residue Cys66 was nucleophilic with a pKa value of ∼6.6; it catalyzed the formation, reduction, and isomerization of disulfide bonds, with the unusual CGAC active site motif being responsible for these activities; and it existed as a dimer and underwent a redox-dependent conformational change. The observations that the redox potential of ERp16 (-165 mV) was within the range of that of the ER (-135 to -185 mV) and that ERp16 catalyzed disulfide isomerization of scrambled ribonuclease A suggest a role for ERp16 in protein disulfide isomerization in the ER. Expression of ERp16 in HeLa cells inhibited the induction of apoptosis by agents that elicit ER stress, including brefeldin A, tunicamycin, and dithiothreitol. In contrast, expression of a catalytically inactive mutant of ERp16 potentiated such apoptosis, as did depletion of ERp16 by RNA interference. Our results suggest that ERp16 mediates disulfide bond formation in the ER and plays an important role in cellular defense against prolonged ER stress.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 is a subcellular compartment specialized for the folding and maturation of proteins destined for secretion or for targeting to the plasma membrane (1, 2). The formation of disulfide bonds is an important step in the maturation of these secreted and membrane proteins (3). The most common mechanism for the formation of such bonds is a thiol-disulfide exchange reaction of free thiols with disulfide-bonded molecules (3). A class of proteins known as thioldisulfide oxidoreductases catalyzes this reaction. The activity of these proteins depends on a CXXC motif, which is usually present in a domain related to the small redox protein thioredoxin (Trx) (4).

The most extensively studied thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase is protein-disulfide isomerase (PDI), which is an abundant ER protein with two redox-active Trx domains (5). PDI catalyzes the formation, reshuffling, or reduction of disulfide bonds in a manner dependent on the redox environment and the characteristics of the substrate protein (6, 7). PDI consists of four structural domains: a, b, b′, and a′ (8). The homologous a and a′ domains share amino acid sequence similarity with Trx and contain the active site sequence, CGHC. Biochemical studies with the isolated domains have shown that the thiol-disulfide exchange reaction requires only the a or a′ domain and that the b′ domain provides a binding site for small peptides (9). Several ER-resident proteins with sequence similarity to PDI have been identified, including ERp57 (also known as GRP58), P5 (CaBP1), PDIp (pancreatic PDI), ERp72 (CaBP2), and PDIR (PDI-related) (8). Although structural information is not yet available for these PDI-like proteins, their domain composition can be predicted on the basis of their sequence similarities. ERp57 and PDIp share a similar domain organization of a-b-b′-a′ with PDI, although the sequences of the b′ domains differ substantially. ERp72 and PDIR harbor three Trx-related domains. Each Trx-like domain of PDIR contains a different active site sequence (CSMC, CGHC, or CPHC), with each motif possibly being optimal for different substrates. These findings suggest that PDI-like proteins perform a similar function but possess distinct substrate binding properties. Additional PDI family members have been identified in the human genome data base, and two PDI-like proteins, ERp28 and ERp44, have been found not to contain the CXXC motif (10-12). This diversity of PDI-like proteins suggests that these proteins possess various substrate specificities and are probably required for disulfide bond formation and correct protein folding in the ER.

Rearrangement of disulfide bonds is also required for efficient protein folding, and the reduction of such bonds in misfolded proteins is necessary for quality control of this process in the ER (10). The accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER results in three cellular responses: (i) transcriptional induction of molecular chaperones, such as BiP (GRP78), and folding enzymes, such as PDI, via a signaling pathway known as the unfolded protein response; (ii) attenuation of translation; and (iii) ER-associated degradation of misfolded proteins (11). Apoptosis is induced if these stress responses are unable to rescue the affected cells (12). Caspase-12, which is localized on the outer membrane of the ER and is processed by calpain in response to ER stress, mediates such apoptosis (13, 14) by activating caspase-9 in a cytochrome c-independent manner (15). In parallel with caspase-12 activation, ER stress triggers the activation of caspase-8, resulting in cytochrome c release and caspase-9 activation via Bid processing (16). Both of these caspase cascades converge on caspase-3, the active form of which mediates the degradation of many apoptotic substrates, including poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (17). However, the function of caspase-12 in human cells is questionable, because those cells are known to express either a truncated protein or a full-length protein with no catalytic activity (18-20).

We have now characterized a novel ER-resident protein, ERp16, that possesses a single Trx-like domain with an atypical active site sequence, CGAC, that has not been detected in other Trx-like proteins. Its biochemical properties suggest that ERp16 may function as a thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase that is required for correct disulfide bond formation in the ER. Furthermore, the effects of overexpression or depletion of ERp16 on ER stress-induced apoptosis suggest that this protein plays an important role in cellular defense against prolonged ER stress.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies—Ribonuclease (RNase) A, cytidine 2′,3′-monophosphate, insulin, and dithiothreitol as well as GSH and GSSG were obtained from Sigma; bovine liver PDI, NADPH, brefeldin A, and tunicamycin were from Calbiochem; the fluorogenic caspase substrate DEVD-aminomethylcoumarin (DEVD-AMC) was from BD Biosciences; and propidium iodide was from Molecular Probes. Rabbit antiserum to ERp16 was generated in response to injection of a purified glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein of human ERp16 according to standard procedures. Mouse monoclonal antibodies to PDI, to BiP (GRP78), and to PARP were obtained from BD Biosciences, and monoclonal antibodies to lamin B, to β-actin, and to α-tubulin were from Calbiochem, Abcam, and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), respectively.

Purification of ERp16 from Mouse Liver and NH2-terminal Sequence Determination—An ER-enriched fraction was prepared from the liver of male C57BL/6 mice as described previously (21). The ER pellet was resuspended in a solution containing 20 mm HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.0), 1 mm EDTA, protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and 0.5% Triton X-100, and the suspension was maintained on ice for 20 min before centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4 °C. Saturated ammonium sulfate solution was slowly added to the resulting supernatant on ice until the concentration reached 1 m, after which the precipitate was removed by centrifugation, and the soluble fraction was applied at a flow rate of 1 ml/min to a TSK Phenyl-5PW 7.5/7.5 column (Tosoh Bioscience) that had been equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.0) containing 1 mm EDTA and 1 m ammonium sulfate. Proteins were eluted from the column with a linear gradient of ammonium sulfate from 1 to 0 m over 120 min at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The fractions corresponding to the peak of ERp16 immunoreactivity were collected and dialyzed against 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1 mm EDTA. The dialyzed proteins were applied to a Mono-Q HR 5/5 column (Amersham Biosciences) that had been equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1 mm EDTA. Proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl from 0 to 0.8 m over 100 min at a flow rate of 0.25 ml/min. The fractions corresponding to the peak of ERp16 immunoreactivity were pooled. All chromatography was performed at 4 °C. For NH2-terminal sequencing, the protein preparation was subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the separated proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). The membrane was stained with Ponceau S (Sigma), and the band corresponding to ERp16 was subjected to automated Edman sequencing with the use of a PerkinElmer Life Sciences 491 protein sequencer at the Korea Basic Science Institute (Seoul, Korea).

Cloning and Mutagenesis of Human ERp16—The DNA sequence encoding mature human ERp16 (amino acids 27-172) was amplified by PCR from human colon cDNA (Clontech) with a forward primer (5′-ACGCCTCATATGCATAATGGGCTTGGAAAGGGTTTTG-3′) containing both an NdeI site (underlined) and the initiation codon (boldface type) and with a reverse primer (5′-GCCTCGAGTTACAATTCATCTTCAAGATGTTTC-3′) containing both a XhoI site (underlined) and the stop codon (boldface type). The amplification product was cloned into the NdeI and XhoI sites of pET-17b (Novagen) for expression in Escherichia coli. For expression of a GST-ERp16 fusion protein, the ERp16 cDNA was cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pGEX4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences). Three ERp16 mutant proteins (C66S, C69S, and CS in which Cys66, Cys69, or both cysteine residues were replaced by serine, respectively) were generated with the use of a QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with complementary primers containing a 1-bp mismatch that converts the codon for cysteine to one for serine. The ERp16 cDNA was also cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pCR3.1 (Invitrogen) for expression in mammalian cells.

Purification of Recombinant ERp16—Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) transformed with pET-17b encoding mature human ERp16 was cultured at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 0.4 mm when the optical density of the culture at 600 nm reached 0.5-0.6. After incubation for an additional 3 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at -70 °C until use. The frozen cells were suspended in an ice-cold solution containing 20 mm HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.0), 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride and were then disrupted by ultrasonic treatment. After removal of nucleic acid from the cell lysate with streptomycin sulfate, the remaining proteins were precipitated by the slow addition of solid ammonium sulfate to 80% saturation at 4 °C and were then dissolved in 20 mm HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.0) containing 1 mm EDTA and 1 m ammonium sulfate. Debris was removed by centrifugation, and the soluble fraction was subjected to sequential high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on TSK Phenyl-5PW 21.5/15 (Tosoh Bioscience) and Mono-Q HR 10/10 (Amersham Biosciences) columns. The chromatographic procedures were similar to those described above for the purification of ERp16 from mouse liver with the exception that the flow rates for the two columns were 5 and 2 ml/min, respectively. The fractions of the Mono-Q HR column corresponding to the peak of ERp16 were pooled and dialyzed against 10 mm HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.0).

The GST-ERp16 fusion protein was purified from E. coli transformed with the corresponding pGEX4T-1 vector by chromatography on GSH-Sepharose resin and was then digested with thrombin at 4 °C. The GST moiety was removed by chromatography on a GSH-Sepharose column, and ERp16 was further purified with the use of a Mono-Q HR 5/5 column.

Confocal Microscopy—HeLa cells cultured on glass coverslips were transfected with pCMV/Myc/ER/GFP (Invitrogen). After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 10 min at room temperature and then immediately washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline. They were exposed to blocking solution (10% fetal bovine serum and 0.02% sodium azide in phosphate-buffered saline) and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with antibodies to ERp16 in blocking solution containing 0.2% saponin. After three washes with blocking solution, the cells were incubated for 1 h with tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated goat antibodies to rabbit immunoglobulin G (Sigma) and then washed an additional three times with blocking solution. The coverslips were mounted on slide glasses with the use of the SlowFade antifade kit (Molecular Probes), and the cells were examined with a laser-scanning confocal microscope system (Zeiss LSM 510).

Determination of Redox Potential—The reduced form of recombinant mature human ERp16 (1 μm) was incubated for 16 h at 25 °C in a solution containing 100 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 1 mm EDTA, 100 μm GSSG, and various concentrations (10 μm to 10 mm) of GSH. Oxidation by air was prevented by degassing the filtered buffer and subsequent flushing with nitrogen as well as by incubation of the protein samples in an anaerobic chamber. The redox state of ERp16 in the glutathione redox buffers was monitored as the change in fluorescence intensity at 335 nm (excitation wavelength of 285 nm). The redox potential of ERp16 was calculated from the equilibrium constant with glutathione and a value of -240 mV for the standard redox potential of the GSH-GSSG redox couple (22).

Determination of pKa Values of Thiol Groups—The thiolate ion has a higher absorbance at 240 nm, with an extinction coefficient (ε240) of ∼4000 m-1 cm-1, than does the unionized thiol group (23). The pKa values of thiol groups can therefore be determined by monitoring UV absorbance during pH titration. The pH of a solution containing 100 μm recombinant mature human ERp16 was titrated within the range of 3-9 by the addition of HCl or NaOH, and A240 was measured. For measurement of only thiolate-dependent A240, the absorbance of a double cysteine mutant of ERp16 (ERp16-CS) was subtracted. The pH-dependent change in ε240 was fitted according to the Henderson-Hasselbach equation to obtain the pKa values of the thiol groups.

Preparation of Reduced, Denatured RNase A or Scrambled RNase A—Reduced, denatured RNase A was prepared by incubating the native enzyme overnight at room temperature in a solution containing 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 100 mm dithiothreitol, 6 m guanidine hydrochloride, and 1 mm EDTA. The reduced, denatured enzyme was separated from dithiothreitol and guanidine hydrochloride by chromatography on a PD10 column (Amersham Biosciences) that had been equilibrated with 10 mm HCl. The RNase A fractions were stored under anaerobic conditions. Scrambled RNase A was prepared by allowing the reduced enzyme to undergo reoxidation under denaturing conditions as described previously (24).

Depletion of ERp16 by RNA Interference—A small interfering RNA that targets human ERp16 mRNA was based on nucleotides 40-58 relative to the translation start site (GGCTTCAGTTTCCTGCTCC). The small interfering RNA was synthesized with the use of T7 RNA polymerase (25) and was introduced into HeLa cells as described previously (26).

RESULTS

Identification and NH2-terminal Sequencing of ERp16—A search of the Conserved Domain Data base with the human Trx1 sequence and with the use of the reverse position-specific BLAST program identified a Trx-like protein (GenBank™ accession number AAH08953; also represented as AAH01493, AAD20035, NP_056997, and AAN34781). A human BLAST search for this protein yielded the clone 24952 mRNA sequence (accession number AF131758), which consists of an open reading frame of 516 bp, a 5′-untranslated region of 110 bp including an in-frame stop codon (TAG), and a 3′-untranslated region containing a putative polyadenylation signal (AATAAA). The predicted open reading frame encodes a protein of 172 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 19.2 kDa. Although this protein has been described previously with three different names (ERp19, ERp18, and hTLP19), it was renamed ERp16, as described below. ERp19 was identified as a new ER protein during mass spectral analysis of ER proteins from mouse liver (27), ERp18 as the result of a data base search for new human PDI-like proteins (28), and hTLP19 as a novel human Trx-like secretory protein.

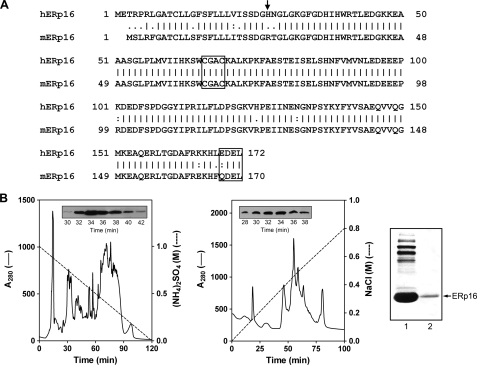

Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of human and mouse ERp16 is shown in Fig. 1A. Both proteins contain a putative NH2-terminal signal sequence and COOH-terminal ER retention motif (EDEL and QDEL in the human and mouse proteins, respectively). Prediction of the NH2-terminal amino acid of the mature ERp16 protein by the PSORT and SignalP programs was not conclusive, with the former identifying Ser24 as the NH2-terminal residue of the human protein and the latter identifying His27 (28, 29). This ambiguous prediction of the cleavage site led the three previous groups that identified ERp16 to prepare recombinant proteins with different NH2 termini and sizes: a 149-residue human protein (Ser24-Leu172) (28), a 150-residue mouse protein (Ser21-Leu170, equivalent to Ser23-Leu172 of the human sequence) (27), and a 146-residue human protein (His27-Leu172) (30).

FIGURE 1.

Primary structure of ERp16 and its purification from mouse liver. A, alignment of the amino acid sequences of human (h) and mouse (m) ERp16. The NH2-terminal residue of the mature protein is indicated with an arrow. The active site sequence (CGAC) and ER retention motif (EDEL or QDEL) are boxed. B, purification of ERp16 from an ER-enriched fraction of mouse liver. ER proteins were subjected to sequential HPLC on Phenyl-5PW (left) and Mono-Q HR (middle) columns as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Insets, immunoblot analysis of column fractions with antibodies to ERp16. Peak fractions (numbers 32-34) from the Mono-Q HR column were pooled. Proteins in the pooled fraction (right, first lane) and recombinant mature human ERp16 (right, second lane) were subjected to SDS-PAGE on an 8% gel, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and stained with Ponceau S. The mouse protein that migrated at the same position as recombinant ERp16 (arrow) was excised from the gel and subjected to NH2-terminal sequencing.

To determine the NH2-terminal sequence of mature ERp16 unambiguously, we purified the protein from an ER fraction of mouse liver by two HPLC steps (Fig. 1B). The protein preparation was further fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and the band corresponding to ERp16 was excised and subjected to NH2-terminal sequencing. The first five residues were determined to be RTGLG (data not shown), indicating that the cleavage site is located between positions 24 and 25 of the mouse sequence, corresponding to positions 26 and 27 of the human sequence. The molecular mass of the predicted mature human protein (amino acids 27-172) was thus calculated to be 16.4 kDa. We therefore renamed this protein ERp16. It possesses a Trx-like domain with a putative active site sequence, CGAC, that has not been previously detected in Trx family members. A BLAST homology search yielded several ERp16 orthologs, multiple sequence alignment of which revealed that the CGAC motif is completely conserved (28).

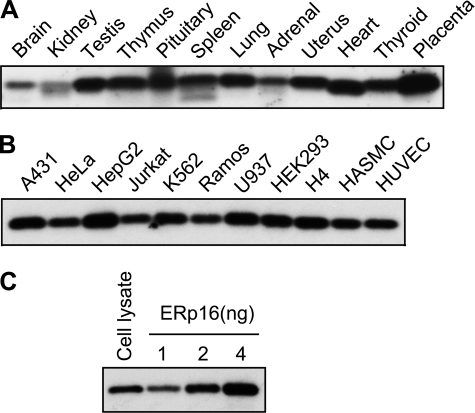

Total soluble fractions prepared from rat tissues and cultured human cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16. ERp16 was detected in most of the tissues examined, being especially abundant in testis, lung, uterus, heart, thyroid, and placenta (Fig. 2A). It was also detected in all human cell lines examined (Fig. 2B). Its abundance in HeLa cells was assessed by immunoblot analysis with the use of recombinant mature human ERp16 (amino acids 27-172) as a reference (Fig. 2C). HeLa cell lysate was thus found to contain 0.15 μg of ERp16/mg of protein (0.015% of total HeLa cell proteins).

FIGURE 2.

Tissue and cellular distribution of ERp16. A and B, total homogenates (20 μg of protein) prepared from rat tissues (A) or total soluble fractions (10 μg of protein) prepared from various human cell lines (B) were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16. HASMC, human aortic smooth muscle cell; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell. C, the relative abundance of ERp16 in HeLa cells was also investigated by subjecting cell lysate (10 μg of protein) and the indicated amounts of purified recombinant mature human ERp16 to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16.

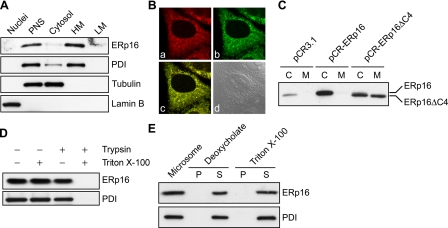

Subcellular Distribution and ER Topology of ERp16—The subcellular localization of ERp16 had not been completely resolved by the previous studies (24-26); ERp18 and ERp19 were found in the ER, whereas hTLP19 was shown to be a secretory protein. To determine the localization of ERp16, we fractionated HeLa cell homogenates into nuclear, organellar, plasma membrane, and cytosolic fractions. Each fraction was then subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16, and successful preparation of the organellar fraction was confirmed with antibodies to PDI (Fig. 3A). ERp16 was detected predominantly in the heavy membrane fraction containing the ER, mitochondria, peroxisomes, and other organelles, suggesting that it is probably localized in the ER. The small amount of ERp16 detected in the cytosolic fraction was probably attributable to leakage from the ER during fractionation, given that a similar amount of PDI also was detected in the cytosolic fraction.

FIGURE 3.

Subcellular localization of ERp16. A, HeLa cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation to yield nuclear, postnuclear supernatant (PNS), and cytosolic as well as heavy (HM) and light (LM) membrane fractions. Equal amounts of protein (10 μg) from each fraction were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16. PDI, lamin B, and α-tubulin were also probed as ER, nuclear, and cytosolic markers, respectively. B, HeLa cells transfected with a vector for ER-GFP were subjected to immunofluorescence staining (red) for ERp16 (a) and were monitored for GFP fluorescence (b). The merged fluorescence image (c) and a differential interference contrast image (d) are also shown. C, HeLa cells were transfected with pCR3.1 (vector alone), pCR-ERp16 (encoding wild-type mature human ERp16), or pCR-ERp16ΔC4 (encoding a COOH-terminal deletion mutant of mature ERp16 lacking the EDEL sequence). After incubation of the cells for 36 h, the culture medium (M) was collected, and the cells (C) were lysed in a volume of lysis solution equal to that of the collected medium. Equal volumes of culture medium and cell lysate were then subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16. D, microsomes isolated from HeLa cells were exposed for 30 min at 35 °C to 0.05% trypsin and to 1% Triton X-100, as indicated. The fractions were then subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16 and to PDI. E, microsomes isolated from HeLa cells were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing either 0.05% sodium deoxycholate plus 0.1 m KCl or 1% Triton X-100 plus 0.6 m KCl, as indicated. After centrifugation, equal proportions of the resulting pellet (P) and supernatant (S) were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16 and to PDI. A corresponding amount of intact microsomes was also probed.

To confirm the ER residency of ERp16, we transiently transfected HeLa cells with a vector for an ER-targeted form of green fluorescent protein (ER-GFP). The cells were then permeabilized and subjected to immunofluorescence analysis with antibodies to ERp16. The pattern of ERp16 immunoreactivity was typical of that for ER marker proteins (Fig. 3B). The cells expressing ER-GFP showed a similar pattern of GFP fluorescence present both surrounding the nucleus and in a network of reticular structures. Moreover, merged images showed that endogenous ERp16 colocalized with ER-GFP. These findings are thus consistent with those of subcellular fractionation.

The putative ER retention sequence of human ERp16 was EDEL, whereas the conventional sequence is KDEL in mammalian cells (31). Given that secretory proteins also reside in the ER until they are secreted, we investigated whether the EDEL sequence is able to mediate ER retention. We transfected HeLa cells with a vector for a COOH-terminal deletion mutant of human ERp16 lacking the EDEL sequence (ERp16ΔC4) and compared the steady state levels of ERp16 in cell culture medium and cell lysates. Whereas endogenous ERp16 was detected almost exclusively in cell lysates, ERp16ΔC4 was distributed equally in both fractions (Fig. 3C). To exclude the possibility that ERp16ΔC4 was secreted because of its overexpression, we also examined HeLa cells overexpressing wild-type ERp16. The overexpressed wild-type protein was detected only in cell lysates. These results thus indicated that the EDEL sequence is responsible for ER retention of ERp16.

To determine the localization of ERp16 within the ER, we performed a protease protection assay with microsomes isolated from HeLa cells. ERp16 was protected from trypsin digestion in the absence of detergent, whereas it was completely digested by trypsin in the presence of 1% Triton X-100 (Fig. 3D). These results indicated that, like PDI, ERp16 is present in the luminal compartment of the ER. High concentrations of nonionic detergents in combination with high salt concentrations solubilize most integral membrane proteins of the ER (32), whereas milder treatment with deoxycholate releases only the cisternal content, with integral membrane proteins remaining in the particulate fraction (33). Both treatments resulted in solubilization of ERp16 (Fig. 3E), indicating that ERp16 is not a membrane protein but rather is an ER luminal protein.

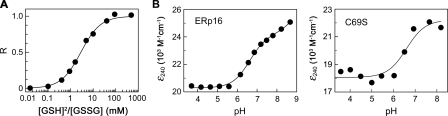

Redox Potential and pKa Values of ERp16—Trx-like proteins function as disulfide reductases, thiol oxidases, or disulfide isomerases, as exemplified by Trx, DsbA, and PDI, respectively. The reductase reaction results in the formation of two free thiols, whereas oxidases catalyze the reverse reaction. The isomerization (oxidoreductase) reaction, a linked cycle of reductionoxidation, does not alter the overall number of disulfides but results in rearrangement of their positions within the substrate protein. Previous observations did not provide a clear indication of the function of ERp16. The 146-residue recombinant hTLP19 protein was found to manifest disulfide reductase activity with insulin as the substrate (30), whereas the 149-residue recombinant ERp18 exhibited thiol oxidase activity with a peptide containing two cysteine residues (28). The 150-residue recombinant ERp19 was tested for neither oxidase nor reductase activity, but when tested for PDI function by yeast complementation analysis, it was found not to be able to substitute for yeast PDI, whereas other mammalian PDI-like proteins could (27). Whether Trx-like proteins act as a reductant or oxidant is largely dependent on their redox potential. The redox potential of cellular reductants ranges from -270 mV for E. coli Trx to -240 mV for GSH, whereas the redox potential of the strong oxidant DsbA of E. coli is -124 mV (34). The redox potential of ERp16 was determined to be about -165 mV by measurement of the equilibrium constant of ERp16 with glutathione at pH 7.0 and 25 °C (Fig. 4A), based on a value of -240 mV for the redox potential of the glutathione redox couple.

FIGURE 4.

Redox potential and pKa values of ERp16. A, redox potential of ERp16. The fraction of reduced ERp16 (R) at equilibrium with glutathione at pH 7.0 and 25 °C was measured on the basis of the redox-dependent change in ERp16 fluorescence at 335 nm (excitation at 285 nm), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, the pKa values of ERp16. The A240 of wild-type (left) and C69S mutant (right) forms of ERp16 was measured at various pH values, and ε240 was plotted against pH and fitted according to the Henderson-Hasselbach equation. The A240 of the cysteine double mutant (ERp16-CS) was subtracted to obtain the pKa values of the two thiols.

The pKa value of the NH2-terminal cysteine residue within the CXXC motif is also an important determinant of thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase activity. Initial nucleophilic attack of the substrate disulfide by the NH2-terminal thiolate anion is required for reductase activity. The thiolate ion can be readily detected on the basis of its absorbance at ∼240 nm (35). We therefore determined the pKa values for the active site cysteines of ERp16 by monitoring its UV absorbance during pH titration (Fig. 4B). To measure only thiolate-dependent A240, we subtracted the absorbance of the ERp16-CS mutant, in which the two active site cysteines are replaced by serine. The values of ε240 were plotted as a function of pH and fitted according to the Henderson-Hasselbach equation, revealing the pKa values of ERp16 to be 6.63 and 8.96. The NH2-terminal cysteine (Cys66) of the CGAC motif appears to be responsible for the lower pKa value, given that the pKa of the C69S mutant was calculated to be 6.60 (Fig. 4B).

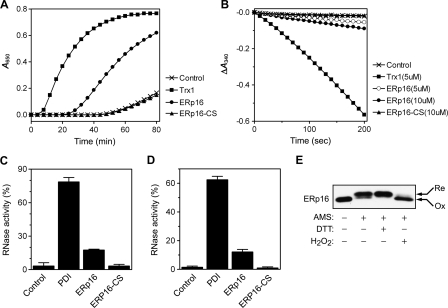

Reductase, Oxidase, and Isomerase Activities of ERp16—The insulin disulfide reductase activity of ERp16 was measured by monitoring the increase in the turbidity of reaction mixtures due to the formation of fine precipitates of the dissociated B chain of insulin (Fig. 5A). In a negative control with dithiothreitol alone, no precipitation was observed during incubation for up to 50 min. The addition of ERp16 or Trx1 resulted in an increase in optical density at 650 nm, whereas the double cysteine mutant of ERp16 (ERp16-CS) failed to reduce insulin. Oxidized Trx1 is reduced by TrxR1 (thioredoxin reductase 1) with electrons of NADPH, and TrxR1 is known to have broad substrate specificity and to reduce oxidized PDI (36). Although ERp16 as an ER luminal protein would not be expected to encounter TrxR1 in the cytosol of cells, TrxR1 was found to reduce oxidized ERp16 in the presence of NADPH in vitro (data not shown). We were therefore able to evaluate the insulin reductase activity of ERp16 in a more quantitative manner by coupling NADPH oxidation to insulin reduction in the presence of TrxR1. Determination of the initial rates of NADPH oxidation suggested that the insulin reductase activity of ERp16 was ∼6% of that of Trx1 (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Reductase, oxidase, and isomerase activities of ERp16. A, ERp16-dependent reduction of insulin monitored on the basis of an increase in turbidity. Reaction mixtures containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 0.3 mm dithiothreitol, and 2.5 μm ERp16, ERp16-CS, or Trx1 were incubated at room temperature for 10 min before the addition of insulin to a final concentration of 0.16 mm and incubation at 30 °C for an additional 80 min. Reductase activity was measured by monitoring the increase in OD at 650 nm. Dithiothreitol alone served as a negative control. B, ERp16-dependent insulin reduction monitored by coupling the reaction to NADPH oxidation. Reduction of insulin by ERp16 was assayed at 30 °C by monitoring A340 in a 0.2-ml reaction mixture containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 0.2 mm NADPH, 50 nm TrxR1, 100 μm insulin, and 5 μm Trx1, 5 or 10 μm ERp16, or 10 μm ERp16-CS. A reaction mixture lacking enzyme served as a control. C, renaturation of reduced, denatured RNase A by ERp16. ERp16, ERp16-CS, or PDI, each at 1 μm, was incubated with 1 mm GSH and 0.2 mm GSSG for 20 min at room temperature before the addition of reduced, denatured RNase A to a final concentration of 20 μm. After incubation for 30 min at 30 °C, a sample of the reaction mixture was removed for determination of RNase activity. The activity was determined by measurement of the increase in A296 of a reaction mixture containing 100 mm HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.0), 0.5 mm cytidine 2′,3′-monophosphate, and 1 μm RNase A, and it is expressed relative to that of the native enzyme. Data are means ± S.E. of values from two independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. D, reactivation of scrambled RNase A by ERp16. ERp16, ERp16-CS, or PDI, each at 1 μm, was incubated with 10 μm dithiothreitol for 20 min at room temperature before the addition of scrambled RNase A to a final concentration of 20 μm. After incubation for 30 min at 30 °C, RNase activity was determined as described in C. E, cellular redox status of ERp16. HeLa cells were exposed or not at 37 °C to 6 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) or 1 mm H2O2, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and then precipitated and washed with 10% trichloroacetic acid. After washing with acetone, the samples were suspended in a reaction mixture containing 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 1 mm EDTA, 1.5% SDS, 1 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride, leupeptin (10 μg/ml), and aprotinin (10 μg/ml), with or without 20 mm 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonate (AMS). They were then incubated for 90 min at 30 °C and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16 under nonreducing conditions. Re and Ox, reduced and oxidized forms of ERp16, respectively.

The oxidase activity of ERp16 was determined by measuring its ability to mediate the oxidative refolding of reduced, denatured RNase A and thereby to yield the catalytically active enzyme. The isomerase activity of ERp16 was similarly determined by measuring its ability to reactivate scrambled RNase A by rearranging its undefined disulfide bonds. PDI from bovine liver was used as a positive control for both activities. ERp16 exhibited ∼22% of the oxidase activity and ∼20% of the isomerase activity of PDI (Fig. 5, C and D). On a per mole active site basis (PDI contains two CXXC domains), these activities of ERp16 correspond to ∼44 and ∼40% of those of PDI, respectively. The cysteine mutant ERp16-CS showed no detectable oxidase or isomerase activity in comparison with the control lacking any enzyme. These results suggested that ERp16 possesses oxidase and isomerase activities for which two cysteine residues (Cys66 and Cys69) are required.

The intracellular redox status of thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases is thought to be an important predictor of their cellular function. To determine the redox state of ERp16 in HeLa cells, we used 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonate, which alkylates free thiol groups and thereby lowers the electrophoretic mobility of proteins (37), given that each bound 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonate moiety theoretically increases the molecular mass of the target protein by 490 Da. ERp16 was found to be partially oxidized in resting cells (Fig. 5E), whereas PDI was present almost exclusively in the reduced form (data not shown). Treatment of cells with dithiothreitol or H2O2 resulted in the complete reduction or oxidation of both proteins, respectively.

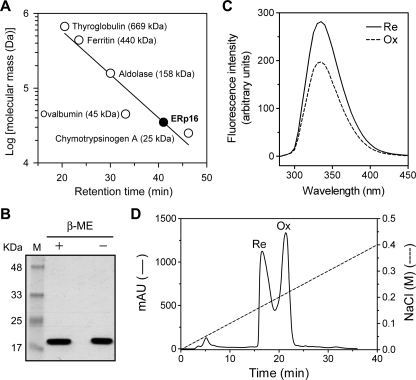

Physical Properties of ERp16—Gel filtration chromatography was performed to determine the molecular size of recombinant mature human ERp16. Its retention time of 41.03 min was less than that (46.2 min) of chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa). Linear regression of the data for the set of gel filtration markers yielded a molecular mass of 34.9 kDa for ERp16 (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the native protein exists as a homodimer. We examined whether the two active site cysteine residues (Cys66 and Cys69) of ERp16 might contribute to such dimerization through formation of intermolecular disulfide bonds. The mobility of ERp16 during SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions was identical to that under reducing conditions (Fig. 6B), however, suggesting that ERp16 exists as a dimer in the ER and forms an intramolecular disulfide upon oxidation.

FIGURE 6.

Physical properties of ERp16. A, purified recombinant human ERp16 (amino acids 27-172) and molecular size markers were subjected to gel filtration on a TSK G3000SW column at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The plot of log molecular mass versus retention time for the markers was fitted by linear regression. B, purified recombinant human ERp16 (4 μg) was subjected to SDS-PAGE in the presence (reducing condition (+)) or absence (nonreducing condition (-)) of β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME). Lane M, molecular size standards. C, the fluorescence emission spectra of oxidized (Ox) and reduced (Re) forms of recombinant human ERp16 were recorded at an excitation wavelength of 285 nm and at 25 °C with the use of a thermostat-controlled spectrofluorometer (Shimadzu). The bandwidth for both excitation and emission was 5 nm. The samples contained 1 μm ERp16 in 2 ml of 20 mm MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.0) and 1 mm EDTA. Reduction of ERp16 was induced by the addition of dithiothreitol to a final concentration of 2 mm. The spectra of appropriate solvent controls were subtracted from those of ERp16. D, partially reduced recombinant human ERp16 was subjected to anion exchange chromatography on a Mono-Q HR 5/5 column that had been equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1 mm EDTA. Protein was eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl from 0 to 0.4 m over 40 min and at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The thiol content of ERp16 in each fraction was determined by spectrophotometric titration with 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) in the presence of 6 m guanidinium chloride and on the basis of an extinction coefficient at 412 nm of 13,700 m-1 cm-1 for thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid.

Fluorescence spectroscopy has shown that reduction of oxidized Trx1 is accompanied by a localized conformational change, as revealed by a 2.5-fold increase in the strongly quenched tryptophan emission of the oxidized protein (38). ERp16 contains two tryptophan residues (Trp40 and Trp65 in the human protein). The fluorescence spectra of ERp16 showed a peak with a λmax of 335 nm (excitation wavelength of 285 nm) under both oxidized and reduced conditions (Fig. 6C). The reduction of oxidized ERp16 was accompanied by a 1.4-fold increase in fluorescence intensity at 335 nm, suggesting that the microenvironment around Trp40 or Trp65 might be changed upon reduction. In addition, oxidized and reduced forms of ERp16 behaved differently on anion exchange chromatography (Fig. 6D). The redox status of ERp16 in each peak was confirmed by spectrophotometric titration with 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) under denaturing conditions. These results thus suggested that ERp16 undergoes a local conformational change that affects its surface properties during a change in redox status.

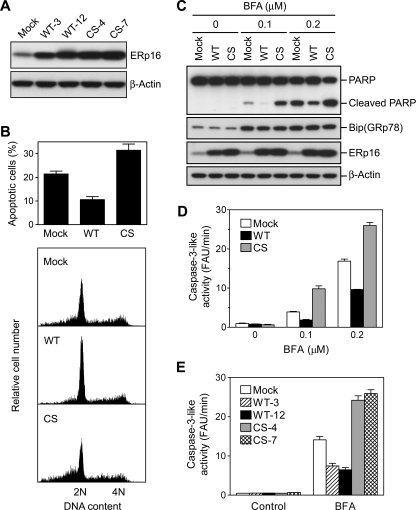

Inhibition of ER Stress-induced Apoptosis by ERp16—To explore the biological function of ERp16, we established HeLa cell lines stably expressing the wild-type protein or the enzymatically inactive mutant ERp16-CS. We isolated clones in which the wild-type or mutant proteins were expressed at a level >10 times that apparent in mock-transfected cells (Fig. 7A). WT-12 and CS-4 were chosen as clones expressing wild-type and mutant ERp16, respectively, because of their similar expression levels for the exogenous proteins. Given that ERp16 is an ER luminal protein with substantial PDI activity, we first examined the effects of its overexpression on ER stress-induced apoptosis. ER stress can be induced by agents such as brefeldin A (which inhibits ER-Golgi transport), tunicamycin (which blocks N-linked protein glycosylation), and dithiothreitol (which prevents the formation of disulfide bonds). Cells were treated with 0.2 μm brefeldin A for 28 h and then stained with propidium iodide for the detection of apoptotic cells (those with a subdiploid (<2 n) DNA content) by flow cytometry. Overexpression of wild-type ERp16 inhibited brefeldin A-induced apoptosis by ∼50%, whereas expression of ERp16-CS increased the level of apoptosis by a factor of ∼1.5 (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Effects of forced expression of ERp16 or the ERp16-CS mutant on brefeldin A-induced apoptosis. A, expression of ERp16 in HeLa cell clones stably transfected with the vector alone (mock), pCR-ERp16 (WT), or pCR-ERp16-CS (CS). Cell lysates (10 μg of protein) were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16 and to β-actin (loading control). B, flow cytometric analysis of brefeldin A-induced apoptosis. Mock-transfected, WT-12, or CS-4 cells were exposed to 0.2 μm brefeldin A for 28 h and were then stained with propidium iodide for flow cytometric analysis of DNA content. The relative cell number was plotted against DNA content (bottom), and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined as that of cells with a subdiploid (<2 n) DNA content (top). C, immunoblot analysis of brefeldin A-induced apoptosis. Lysates (20 μg of protein) of cells treated (or not) with 0.1 or 0.2 μm brefeldin A (BFA) for 28 h as in B were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to PARP, to BiP (GRP78), to ERp16, and toβ-actin. D-E, caspase-3-like activity in brefeldin A-treated cells. WT-12 and CS-4 cells (D) or the indicated HeLa cell lines (E) were incubated for 28 h with the indicated concentrations of brefeldin A (D) or in the absence or presence of 0.2 μm brefeldin A (E), after which total cell lysates (10 μg of protein) were incubated at 37 °C in a reaction mixture of 200 μl containing 100 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 10% (w/v) sucrose, 0.1% CHAPS detergent, 10 mm dithiothreitol, and 25 μm DEVD-AMC. The amount of AMC liberated from DEVD-AMC was measured with the use of a CytoFluor 4000 fluorescence multiwell plate reader (PerSeptive Biosystems) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 380 and 460 nm, respectively. Caspase-3-like activity was determined as the reaction rate in fluorescence arbitrary units (FAU)/min. Data in B (top), D, and E are means ± S.E. of values from three independent experiments.

We next examined the effects of forced expression of ERp16 on PARP cleavage to probe further its role in brefeldin A-induced apoptosis. The cleavage of PARP was inhibited by overexpression of wild-type ERp16 but was markedly potentiated by expression of ERp16-CS (Fig. 7C). All cells responded to ER stress by eliciting the unfolded protein response, as revealed by induction of BiP (GRP78). The brefeldin A-induced increase in caspase-3-like activity, measured with a fluorogenic substrate (DEVD-AMC), was also inhibited by wild-type ERp16 and enhanced by ERp16-CS (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, these effects of the wild-type and mutant forms of ERp16 were apparent in another pair of stable cell lines, WT-3 and CS-7 (Fig. 7E). Together, these results thus suggested that wild-type ERp16 suppresses brefeldin A-induced apoptosis, whereas the inactive mutant ERp16-CS augments it.

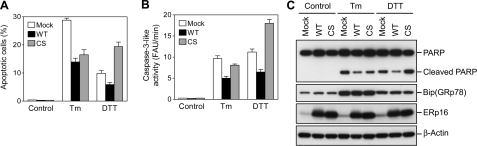

We also investigated the effects of ERp16 expression on apoptosis induced by tunicamycin or dithiothreitol. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that overexpression of wild-type ERp16 inhibited apoptosis induced by treatment of cells with 3 μm tunicamycin for 54 h or with 6 mm dithiothreitol for 12 h (Fig. 8A). Expression of ERp16-CS potentiated dithiothreitol-induced apoptosis but inhibited that induced by tunicamycin. Similar effects of ERp16 and ERp16-CS were also apparent on caspase-3-like activity (Fig. 8B) and PARP cleavage (Fig. 8C). The induction of BiP (GRP78) by tunicamycin or dithiothreitol in all cells confirmed that these agents elicited ER stress (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

Effects of forced expression of ERp16 or ERp16-CS on apoptosis induced by tunicamycin or dithiothreitol. HeLa cells stably expressing wild-type ERp16 (WT) or ERp16-CS (CS) were treated with 3 μm tunicamycin (Tm) for 54 h or with 6 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) for 12 h, after which they were subjected to flow cytometric analysis of the number of apoptotic cells (A), to assay of caspase-3-like activity (B), or to immunoblot analysis (C) as described in the legend to Fig. 7. Data in A and B are means ± S.E. of values from three independent experiments. FAU, fluorescence arbitrary units.

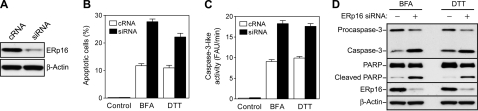

To investigate the possible role of endogenous ERp16 in ER stress-induced apoptosis, we examined the effect of depletion of ERp16 by RNA interference on this process. About 60 h after transfection of cells with a small interfering RNA specific for ERp16 mRNA, the abundance of ERp16 was reduced by ∼90% compared with that in cells transfected with a control RNA (Fig. 9A). Such depletion of ERp16 resulted in ∼2-fold increases in both the number of apoptotic cells and caspase-3-like activity in cells treated with brefeldin A or dithiothreitol (Fig. 9, B and C). The cleavage of both procaspase-3 and PARP induced by these two agents was also enhanced by depletion of ERp16 (Fig. 9D). These results thus indicated that endogenous ERp16 suppresses apoptosis induced by ER stress.

FIGURE 9.

Effects of ERp16 depletion on ER stress-induced apoptosis. A, HeLa cells were transfected with ERp16 small interfering RNA or a control RNA (cRNA) for ∼60 h, after which cell lysates (20 μg of protein) were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to ERp16 and to β-actin. B-D, cells transfected as in A were treated with 0.2 μm brefeldin A (BFA) for 28 h or with 6 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) for 12 h, after which they were subjected to flow cytometric analysis of the number of apoptotic cells (B), to assay of caspase-3-like activity (C), or to immunoblot analysis (D), as described in Fig. 7. Data in B and C are means ± S.E. of values from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized a Trx-like protein that harbors a putative NH2-terminal signal sequence and COOH-terminal ER retention motif (EDEL in the human protein) and was previously described with the name ERp18, ERp19, or hTLP19 (27, 28, 30). Direct determination of the NH2-terminal sequence of the purified mouse protein indicated that the 172-residue human precursor is processed to a mature form comprising 146 amino acids by cleavage of the 26-residue signal peptide. The calculated molecular mass of the mature form of the human protein is 16.4 kDa. We therefore renamed the protein ERp16 (ER-resident protein of 16 kDa). The previous names of ERp19 and ERp18 were assigned on the basis of the molecular mass of the precursor protein and of the recombinant protein consisting of 149 amino acids (assuming that cleavage of the signal peptide occurs between residues 23 and 24) attached to a His6 tag, respectively. Our subcellular fractionation and immunofluorescence analyses revealed ERp16 to be an ER protein, as previously demonstrated for ERp19 and ERp18 (27, 28). The specific localization of ERp16 in the luminal compartment of the ER was demonstrated on the basis of its sensitivity to trypsin digestion. Although the typical ER retention sequence is KDEL in mammalian cells (39), deletion analysis showed that the EDEL sequence at the COOH terminus of human ERp16 mediates ER retention of the protein. The previous identification of hTLP19 as a secretory protein may have been an artifact resulting from overexpression of Myc-tagged hTLP19 and its detection with antibodies to Myc (30).

We found that ERp16 is widely expressed in rat tissues and human cell lines, and its cDNA was detected in several human tissues, including kidney, brain, prostate, pancreas, ovary, colon, skin, and placenta, suggesting that ERp16 may be ubiquitous in mammalian cells. Although the active site sequence of ERp16, CGAC, has not been found in other Trx family members, this motif was shown to be required for disulfide reductase, thiol oxidase, and disulfide isomerase activities, as revealed by assays based on the reduction of insulin, oxidation of reduced RNase A, and isomerization of scrambled RNase A. In addition, the active site cysteine Cys66 of human ERp16 was shown to be nucleophilic, with a pKa value of ∼6.6.

Comparison of the relative redox potentials of Trx-like proteins is a means of predicting whether they function as reductants, oxidants, or isomerases in vivo. For example, a role for Trx1 as a cytosolic reductase is predicted from the finding that its redox potential (-270 mV) is more reducing than that of the cytoplasm (-220 to -240 mV), whereas the redox potential of the strong oxidant DsbA is -124 mV (34). The redox potential of ERp16 as determined by an assay based on redox equilibrium with glutathione was about -165 mV. The redox potential of the ER is in the range of -135 to -185 mV (3). The intracellular redox status of oxidoreductases is also an important predictor of cellular function. The cellular reductant Trx1 exists predominantly in the reduced form (40), whereas the oxidant DsbA is present exclusively in the oxidized form (37). In resting cells, most ERp16 was present in the reduced form, but a substantial proportion was found to be in the oxidized form, suggesting that this protein functions as both a reductase and an oxidase. Together, these various observations indicate that ERp16 may function as a disulfide isomerase in the ER, as does PDI, which has a redox potential of -150 mV (3). Indeed, ERp16 exhibited disulfide isomerase activity with scrambled RNase A that was ∼40% of that of PDI on a per mole active site (CXXC) basis. Reshuffling of disulfide bonds first requires reduction of these bonds by an isomerase. PDI was previously shown to possess 1-2% of the insulin disulfide reductase activity of mammalian Trx1 (36), whereas we found that ERp16 exhibited 6% of the insulin disulfide reductase activity of Trx1. The disulfide reduction step is thus not likely to be responsible for the slower isomerase activity of ERp16 compared with that of PDI. Instead, a difference in the rates of formation of disulfides between the correct pairs of cysteine residues might be largely responsible for the slower isomerase activity of ERp16. The oxidase activity of ERp16 was only ∼44% of that of PDI on a per mole active site basis. PDI possesses b and b′ domains in addition to the catalytic a and a′ domains, whereas ERp16 does not contain b and b′ domains. The b′ domain is implicated in substrate binding (41).

Accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER induces ER stress, with prolonged ER stress leading to apoptosis (12, 42). Several ER-resident proteins, including BiP, PDI, ERp57, and ERp72, are induced by ER stress, but we found that ERp16 was not inducible. We have now shown that overexpression of ERp16 in HeLa cells attenuated the induction of apoptosis by brefeldin A, tunicamycin, or dithiothreitol, whereas depletion of ERp16 potentiated ER stress-induced apoptosis. This inhibitory role of ERp16 in apoptosis induced by ER stress is probably dependent on its thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase activity, given that expression of the catalytically inactive mutant ERp16-CS enhanced the apoptotic response to brefeldin A or dithiothreitol. The dominant negative effect of this mutant protein on apoptosis is probably due to the formation of a heterodimer with the endogenous wild-type protein or to competition with the wild-type protein for association with substrates. Given that dithiothreitol penetrates cell membranes and reversibly inhibits protein oxidation in the ER, inhibition of dithiothreitol-induced apoptosis by ERp16 suggests that this protein contributes to disulfide bond formation by nascent proteins. ERp16-CS inhibited tunicamycin-induced apoptosis, suggesting that ERp16 may affect the tunicamycin-induced apoptosis in an oxidoreductase-independent manner.

Our results suggest that ERp16 is a novel thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase in the ER and plays an important role in cellular defense against prolonged ER stress. PDI and related proteins, such as ERp57 and ERp44, interact with other ER proteins and regulate their functions. For example, PDI and ERp57 interact with calreticulin and regulate its chaperone function (43); ERp57 interacts with SERCA (sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase) and modulates the redox state of thiol groups of this protein that face the lumen of the ER, providing dynamic control of Ca2+ homeostasis in the ER in a manner dependent on ER redox status (44); and ERp44 interacts with the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and thereby inhibits its Ca2+ release function (45). The redox status-dependent changes in the conformation and chromatographic behavior of ERp16 observed in the present study suggest that its potential interaction with target proteins may be regulated by changes in its redox state. Further characterization of the precise biological function of ERp16 will require the identification of interacting proteins as well as structural comparison of the reduced and oxidized forms of ERp16.

This work was authored, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health staff. This work was supported by Bio R&D Program Grants M10642040002-07N4204-00210 (to W. J.) and M10642040001-07N4204-00110 (to S. G. R.), National Honor Scientist Program Grant R09-2006-000-10002-0 (to S. G. R.), and National Core Research Center Program Grant R15-2006-020 (to W. J.) through the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, and by the Brain Korea 21 Scholars Program (to S. P). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Trx, thioredoxin; PDI, protein-disulfide isomerase; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; RNase A, ribonuclease A; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; GFP, green fluorescent protein; AMC, aminomethylcoumarin; CHAPS, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid.

References

- 1.Stevens, F. J., and Argon, Y. (1999) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 10 443-454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellgaard, L., and Helenius, A. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4 181-191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sevier, C. S., and Kaiser, C. A. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3 836-847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmgren, A. (1985) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 54 237-271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman, R. B., Hirst, T. R., and Tuite, M. F. (1994) Trends Biochem. Sci. 19 331-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman, R. B. (1989) Cell 57 1069-1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noiva, R. (1999) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 10 481-493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrari, D. M., and Soling, H. D. (1999) Biochem. J. 339 1-10 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman, R. B., Klappa, P., and Ruddock, L. W. (2002) EMBO Rep. 3 136-140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fassio, A., and Sitia, R. (2002) Histochem. Cell Biol. 117 151-157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mori, K. (2000) Cell 101 451-454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferri, K. F., and Kroemer, G. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3 E255-E263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakagawa, T., Zhu, H., Morishima, N., Li, E., Xu, J., Yankner, B. A., and Yuan, J. (2000) Nature 403 98-103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakagawa, T., and Yuan, J. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150 887-894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morishima, N., Nakanishi, K., Takenouchi, H., Shibata, T., and Yasuhiko, Y. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 34287-34294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jimbo, A., Fujita, E., Kouroku, Y., Ohnishi, J., Inohara, N., Kuida, K., Sakamaki, K., Yonehara, S., and Momoi, T. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 283 156-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casciola-Rosen, L., Nicholson, D. W., Chong, T., Rowan, K. R., Thornberry, N. A., Miller, D. K., and Rosen, A. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183 1957-1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer, H., Koenig, U., Eckhart, L., and Tschachler, E. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293 722-726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saleh, M., Vaillancourt, J. P., Graham, R. K., Huyck, M., Srinivasula, S. M., Alnemri, E. S., Steinberg, M. H., Nolan, V., Baldwin, C. T., Hotchkiss, R. S., Buchman, T. G., Zehnbauer, B. A., Hayden, M. R., Farrer, L. A., Roy, S., and Nicholson, D. W. (2004) Nature 429 75-79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinon, F., and Tschopp, J. (2007) Cell Death Differ. 14 10-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amar-Costesec, A., Beaufay, H., Wibo, M., Thines-Sempoux, D., Feytmans, E., Robbi, M., and Berthet, J. (1974) J. Cell Biol. 61 201-212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber-Wunderlich, M., and Glockshuber, R. (1998) Fold Des. 3 161-171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graminski, G. F., Kubo, Y., and Armstrong, R. N. (1989) Biochemistry 28 3562-3568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkins, H. C., Blackburn, E. C., and Freedman, R. B. (1991) Biochem. J. 275 349-353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donze, O., and Picard, D. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30 e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong, W., Chang, T. S., Boja, E. S., Fales, H. M., and Rhee, S. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 3151-3159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knoblach, B., Keller, B. O., Groenendyk, J., Aldred, S., Zheng, J., Lemire, B. D., Li, L., and Michalak, M. (2003) Mol. Cell Proteomics 2 1104-1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alanen, H. I., Williamson, R. A., Howard, M. J., Lappi, A. K., Jantti, H. P., Rautio, S. M., Kellokumpu, S., and Ruddock, L. W. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 28912-28920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen, H., Engelbrecht, J., Brunak, S., and von Heijne, G. (1997) Protein Eng. 10 1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, F., Rong, Y. P., Zeng, L. C., Zhang, X., and Han, Z. G. (2003) Gene (Amst.) 315 71-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teasdale, R. D., and Jackson, M. R. (1996) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12 27-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hjelmeland, L. M., and Chrambach, A. (1984) Methods Enzymol. 104 305-318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreibich, G., and Sabatini, D. D. (1974) J. Cell Biol. 61 789-807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aslund, F., Berndt, K. D., and Holmgren, A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 30780-30786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lo Bello, M., Parker, M. W., Desideri, A., Polticelli, F., Falconi, M., Del Boccio, G., Pennelli, A., Federici, G., and Ricci, G. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 19033-19038 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lundstrom, J., and Holmgren, A. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265 9114-9120 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi, T., Kishigami, S., Sone, M., Inokuchi, H., Mogi, T., and Ito, K. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 11857-11862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holmgren, A. (1972) J. Biol. Chem. 247 1992-1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munro, S., and Pelham, H. R. (1987) Cell 48 899-907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watson, W. H., and Jones, D. P. (2003) FEBS Lett. 543 144-147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klappa, P., Ruddock, L. W., Darby, N. J., and Freedman, R. B. (1998) EMBO J. 17 927-935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaufman, R. J. (1999) Genes Dev. 13 1211-1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corbett, E. F., and Michalak, M. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25 307-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li, Y., and Camacho, P. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 164 35-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higo, T., Hattori, M., Nakamura, T., Natsume, T., Michikawa, T., and Mikoshiba, K. (2005) Cell 120 85-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]