Abstract

The kinetics of redox reactions of the PtIV complexes, trans-Pt(d,l)(1,2-(NH2)2C6H10)Cl4 ([PtIVCl4(dach)]) and Pt(NH2CH2CH2NH2)Cl4 ([PtIVCl4(en)]), with 5′- and 3′-dGMP (G) has been studied. These redox reactions involve substitution followed by an inner-sphere electron transfer. The substitution is catalyzed by PtII and follows the classic Basolo-Pearson PtII-catalyzed PtIV-substitution mechanism. We found that the substitutution rates depend on the steric hindrance of PtII, G, and PtIV with the least sterically hindered PtII complex catalyzing at the highest rate. 3′-dGMP undergoes substitution faster than 5′-dGMP, and [PtIVCl4(en)] substitutes faster than [PtIVCl4(dach)]. The enthalpies of activation of the substitution, ΔH‡s, of 3′-dGMP is only 70% greater than that of 5′-dGMP (50.4 vs. 30.7 kJ mol−1), but the entropy of activation of the substitution, ΔS‡s, of 3′-dGMP is much greater than that of 5′-dGMP (−59.4 vs. −129.5 J K−1 mol−1), indicating that steric hindrance plays a major role in the substitution. The enthalpy of activation of electron transfer, ΔH‡e, of 3′-dGMP is smaller than that of 5′-dGMP (88.8 vs. 137.8 kJ mol-1). The entropy of activation of electron transfer, ΔS‡e, of 3′-dGMP is negative but that of 5′-dGMP is positive (−27.8 vs. +128.8 J K−1 mol−1). The results indicate that 5′-hydroxo has less rotational barrier than 5′-phosphate, but is geometrically unfavorable for internal electron transfer. The electron transfer rate also depends on the reduction potential of PtIV. Due to its higher reduction potential, [PtIVCl4(dach)] has a faster electron transfer than [PtIVCl4(en)].

Introduction

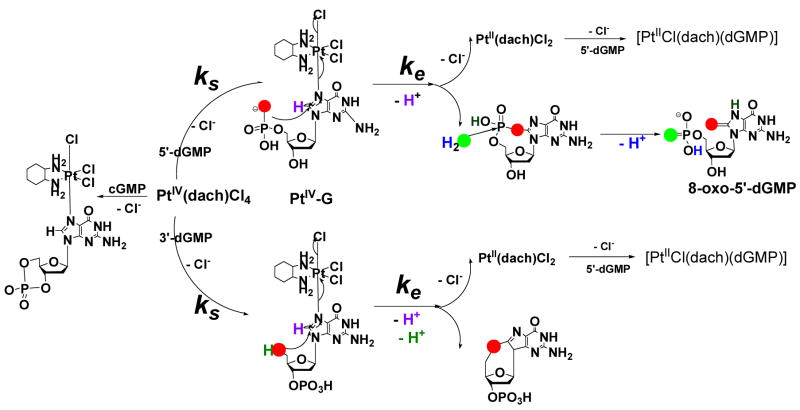

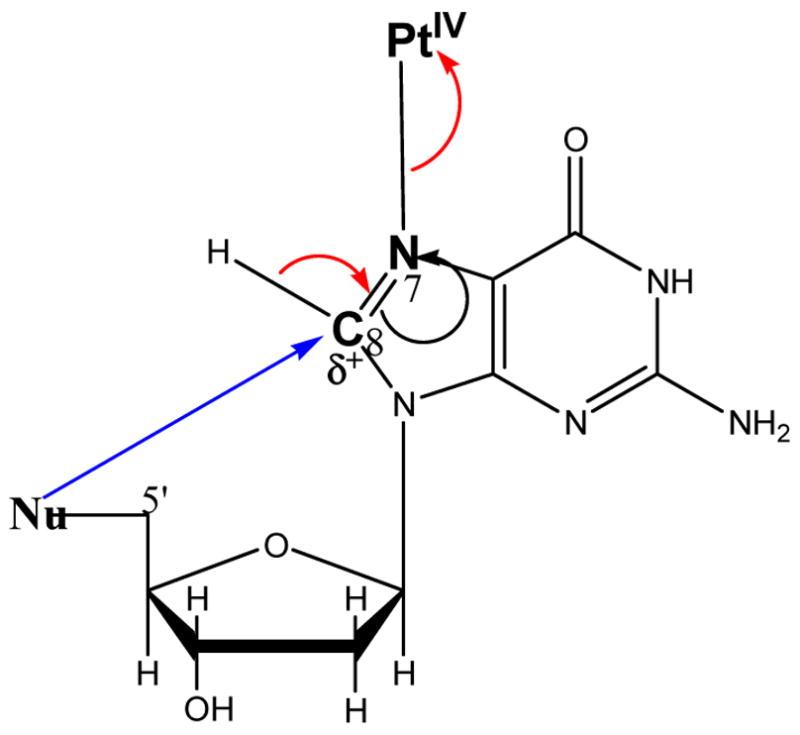

Platinum complexes are biologically important because of their anticancer activities. In particular, the interaction of DNA with PtII complexes has been extensively studied.1 On the other hand PtIV complexes, which are relatively inert, have not been the focus of much research because potential reactivity with DNA is not generally expected for such inert molecules. However our lab recently discovered that trans-Pt(d,l)(1,2-(NH2)2C6H10)Cl4, [PtIVCl4(dach)], oxidizes 5′-dGMP, 3′-dGMP and 5′-d[GTTTT]-3′.2 The proposed mechanism involves PtIV binding to N7 of the guanosine (G) moiety followed by nucleophilic attack of a 5′-phosphate or a 5′-hydroxyl oxygen to C8 of the G moiety and an inner-sphere, two-electron transfer to produce cyclic (5′-O-C8)-G and a PtII complex (Scheme 1). The identity of the final oxidized G depends on the hydrolysis rate of the cyclic intermediate. The cyclic phosphodiester intermediate formed from [PtIVCl4(dach)]/5′-dGMP is hydrolyzed to 8-oxo-5′-dGMP. However the cyclic ether intermediate formed from [PtIVCl4(dach)]/3′-dGMP (or 5′-d[GTTTT]) does not hydrolyze, and this cyclic form is the final oxidation product. The PtIV complex simply binds to N7 of the G moiety in 3′,5′-cyclic guanosinemonophosphate (cGMP), 9-methylxanthine (9-Mxan), 5′-d[TTGTT]-3′ and 5′-d[TTTTG]-3′ without further redox reaction. These prior results indicate that a nucleophilic group at the 5′ position is required for the redox reaction between G and the PtIV complex.

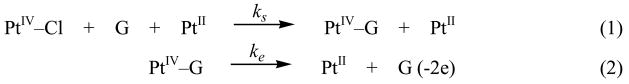

Scheme 1.

Proposed Mechanism for the Reaction of [PtIVCl4(dach)] with 5′-dGMP, 3′-dGMP and cGMP.2a,b

Although the kinetics of PtII complex binding to DNA is fairly well understood,3,4 the corresponding PtIV chemistry is not. Roat and co-workers reported that the reaction of several PtIV complexes with 9-Mxan undergo PtII-catalyzed PtIV substitution reactions without autocatalysis, where the added PtII catalysts were PtIV analogs.5 Elding’s group established a redox mechanism for reductive elimination at PtIV where two electrons transfer between the reductant (thiol or ascorbate) and the PtIV via a halide ligand.6 Several other groups reported the autocatalytic nature of PtIV reduction by ascorbate via an outer- as well as an inner-sphere one electron transfer.7 None of these cases have a mechanism similar to the [PtIVCl4(dach)]/dGMP redox reaction, where substitution precedes inner-sphere two electron transfer.2a.b

In our previous work,2a we observed that 3′- and 5′-dGMP reactions with [PtIVCl4(dach)] were autocatalyzed, and 3′-dGMP reacted faster than 5′-dGMP. The aim of the present work is to expand on our earlier studies of substitution and electron transfer mechanism by use of quantitative kinetic measurements. Using an autocatalytic kinetic model and the DynaFit Software,8 we obtained the substitution rate constant (ks) and the electron transfer rate constant (ke). Activation parameters were obtained from the rate constants at temperatures between 30 and 45 °C. We also compared the [PtIVCl4(dach)] reaction rates to [PtIVCl4(en)] to see how the size of the carrier ligand and the reduction potential of PtIV complexes affect substitution and electron transfer rates. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first detailed kinetic study of a PtIV/DNA reaction.

Experimental Section

Sample Preparation

[PtIVCl4(dach)] was obtained from the National Cancer Institute, Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, Developmental Therapeutics Program, Division of Cancer Treatment. The [PtIICl2(diam)] and [PtII(tetam)] complexes were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. [PtIICl2(dach)],9a [PtIICl2(en)]9b and [PtIVCl4(en)]9b were synthesized following previously published procedures. They were characterized by IR (Bruker Equinox 55 Spectrometer), 1H NMR (Bruker 400 Ultrashield spectrometer), and HPLC (Waters Alliance 2695 equipped with a Waters 2996 Photodiode Array Detector and a Waters Atlantis dC18 column). [PtIICl(dach)(5′-dGMP)] and [PtII(diam)(5′dGMP)2] were synthesized by the reactions of 5′-dGMP with stoichiometric amounts of [PtIICl2(dach)] and [PtIICl2(diam)] respectively. Stock platinum complex solutions were prepared by dissolving in saline water (0.1 M NaCl, pH 8.3~8.6). pH 8.3–8.6 was used to fully deprotonate the phosphate group in dGMP,10 and 0.1 M NaCl solution was used to prevent hydrolysis of the platinum complexes.

Mass Spectrometry

Liquid Chromatography/Mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analyses were conducted on an 1100 Series LC and LC/MSD Trap XCT Plus from Agilent Technologies. The LC component was equipped with a photodiode array detector and an Eclipse X-D8-C8 Column (5 m, 4.6 mm ×150 mm) running isocratic (0.5 mL/min) conditions with a solvent of 0.5% formic acid in water. An ion trap mass spectrometer to select for specific masses was used with fragmentation both on and off. The MS parameters were set to scan from 50–2200 m/z using positive detection with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). For tuning, the nebulizer was set to 50 psi, the dry gas flow to 9 L/min and the dry temperature to 365 °C.

Kinetic Studies

To achieve the desired dGMP concentrations, appropriate amounts of 3′- or 5′-dGMPwere added to vials containing equal volumes of platinum stock and saline solutions. The pH values of the solutions were adjusted to pH 8.3 with NaOH using a pH meter (Orion Research 960) equipped with a Mettler-Toledo Inlab combination pH microelectrode. Attainment of desired the pH constituted the beginning of the reaction. UV/visible spectra were obtained in 10-mm cells on a Varian Cary 4000i Spectrophotometer with Cary WinUV kinetic assay software. The absorbances at 360 and 390 nm were monitored. The sample temperature was maintained by a Varian-Cary temperature controller. Kinetic experiments were repeated at least three times.

Results and Discussion

Effect of added PtII complexes on the reaction of [PtIVCl4(dach)] and 5′-dGMP

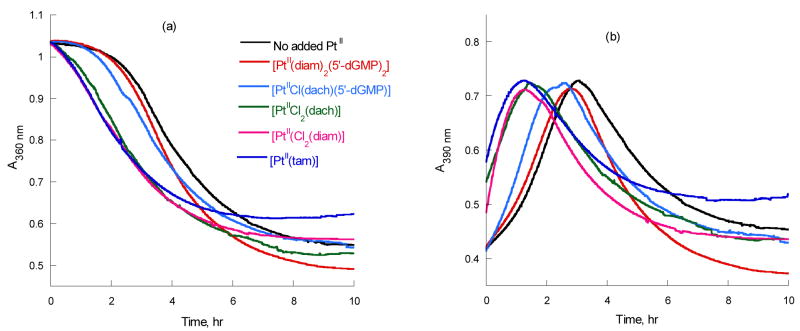

Figure 1 compares the A360 and A390 versus time of the reactions of [PtIVCl4(dach)] and 5′-dGMP without and with added PtII complexes such as [PtIICl2(dach)], [PtIICl(dach)(5′-dGMP)], [PtIICl2(diam)], [PtIICl(diam)(5′-dGMP)2], and [PtII(tetam)]. The absorbances at 360 and 390 nm are mainly due to initial [PtIVCl4(dach)] and the intermediate [PtIVCl3(dach)(5′-dGMP)] ([PtIV–G]), respectively.2a,b Without added PtII catalysts, there is a long induction time for the reaction to start. All of the PtII complexes shorten the induction time (Figure 1a) and produce the [PtIV–G] intermediate at an earlier time, than when the reaction is run without a catalyst (Figure 1b). Without added PtII, the [PtIV–G] intermediate reached maximum concentration around 3 hrs, but with the addition of 10% (mol) of [PtII(diam)(5′-dGMP)2], [PtIICl(dach)(5′-dGMP)], [PtIICl2(dach)], [PtIICl2(diam)], and [PtII(tetam)] it became 2.78, 2.52, 1.48, 1.28, and 1.27 hrs, respectively. The smallest catalysts, [PtII(tetam)] and [PtIICl2(diam)] are the most efficient, followed by [PtIICl2(dach)], [PtIICl(dach)(5′-dGMP)], and [PtII(diam)(5′-dGMP)2] in order, coinciding with increasing ligand size.

Figure 1.

Absorbance at (a) 360 nm (b) 390 nm vs time of 5 mM [PtIVCl4(dach)] and 50 mM 5′-dGMP with 0.5 mM PtII complexes, pH 8.6 at 37 °C.

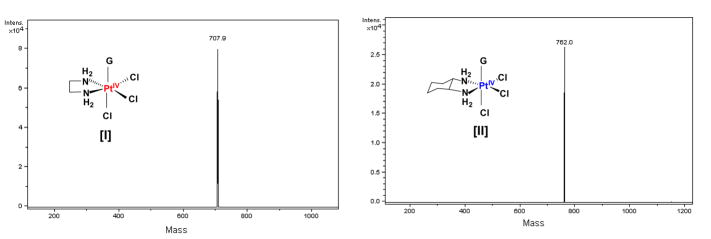

Identification of Intermediate, PtIV G

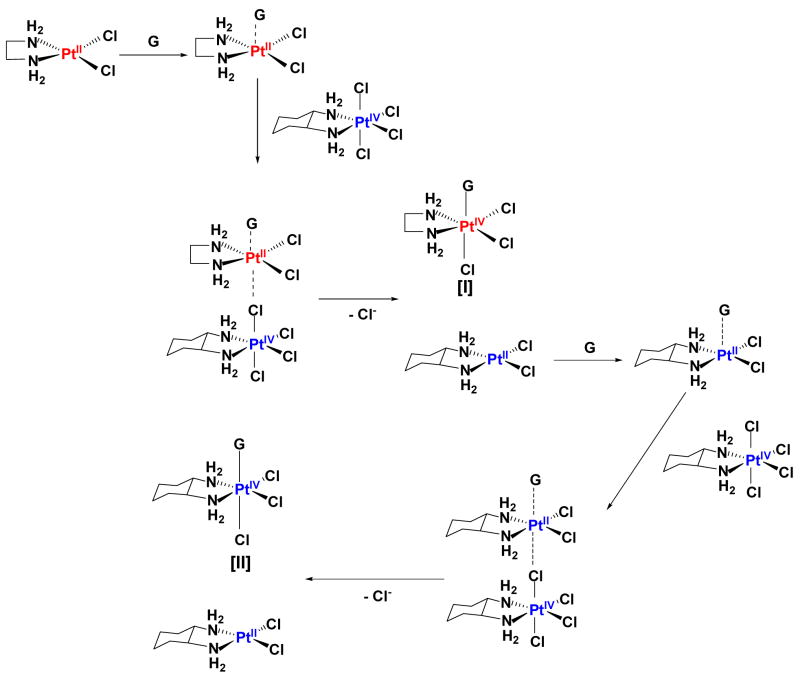

In order to further elucidate the substitution reaction, the PtIV–G intermediates of the [PtIVCl4(dach)]/5′-dGMP reaction catalyzed by [PtIICl2(en)] and by [PtIICl2(dach)] were identified by LC/MS. The LC/MS was performed on each reaction when the intermediate concentration observed by A390 nm was maximum. Figure 2 displays the LC/MS spectra of the [PtIVCl4(dach)]/[PtIICl2(en)]/5′-dGMP reaction. It shows a 707.9 amu peak due to [PtIVCl3(en)(5′-dGMP)] (I) as well as a 762.0 amu peak due to [PtIVCl3(dach)(5′-dGMP)] (II). The LC/MS spectrum of [PtIVCl4(dach)]/[PtIICl2(dach)]/5′-dGMP reaction only shows a 762 amu peak due to [PtIVCl3(dach)(5′-dGMP)] (II). These results are best explained by consideration of the Basolo-Pearson PtII catalyzed PtIV substitution reaction where the central platinum is exchanged between PtII catalyst and PtIV substrate (Scheme 2).11 For the [PtIVCl4(dach)]/[PtIICl2(en)]/5′-dGMP reaction, 5′-dGMP binds to PtIICl2(en) to produce 5-coordinate [PtIICl2(en)(5′-dGMP)], which then binds to [PtIVCl4(dach)] through a chloro ligand to form [PtIVCl3(dach)Cl…PtIICl2(en)(5′-dGMP)]. Two electrons transfer from PtII to PtIV through chloride ligand to generate [PtIICl2(dach)] and [PtIVCl3(en)(5′-dGMP)]. In the subsequent reaction, 5′-dGMP binds to [PtIICl2(dach)] to produce 5-coordinate [PtIICl2(dach)(5′-dGMP)], which then binds to [PtIVCl4(dach)] through a chloro ligand to form [PtIVCl3(dach)Cl…PtIICl2(dach)(5′-dGMP)]. Two electrons transfer from PtII to PtIV through a chloride ligand to generate [PtIICl2(dach)] and [PtIVCl3(dach)(5′-dGMP)].

Figure 2.

Mass spectra of [PtIVCl3(en)(5′-dGMP)] (I) and [PtIVCl3(dach)(5′-dGMP)] (II). The intermediate complex was acquired using the ion trap set for a mass of (I) 708 amu and (II) 762 with no fragmentation from the reaction of [PtIVCl4(dach)]/[PtII(en)Cl2]/5′-dGMP (1 mM/0.7 mM/10 mM). The [PtIVCl4(dach)]/[PtIICl2(dach)]/5′-dGMP (1 mM/0.7 mM/10 mM) reaction generates only II.

Scheme 2.

PtII-catalyzed PtIV substitution reaction.

Kinetic data analysis of 3′- and 5′-dGMP reactions with [PtIVCl4(dach)]

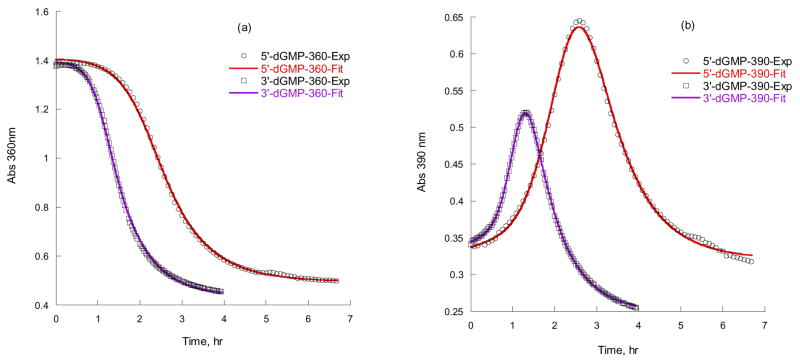

The time courses of 5 mM [PtIVCl4(dach)] reactions with 50 mM 5′- or 3′-dGMP at 40 °C are displayed in Figure 3. The A360 curve of 3′-dGMP has a much shorter induction time than 5′-dGMP, and the A390 curve shows that the intermediate [PtIV–3′-dGMP] reaches a maximum faster than for [PtIV–5′-dGMP] (3 hr vs. 1 hr). The kinetic curves are sigmoidal-shaped indicating autocatalysis. The mechanism shown in Scheme 1 is a combination of a substitution reaction and an inner-sphere electron transfer reaction. As demonstrated by the identity of the PtIV–G intermediate (Figure 2), the substitution follows the Basolo-Pearson PtII-catalyzed PtIV substitution mechanism, and therefore the overall substitution reaction can be written as equation (1) in Scheme 3.11 Even if no external PtII is added, a small amount is assumed to be present as an impurity.

Figure 3.

A360 (a) and A390 (b) vs. time of 5 mM [PtIVCl4(dach)] with 50 mM 5′- and 3′-dGMP reactions in 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.3 at 40 °C. Both fits give ks = 20.4 M−2s−1 and ke = 3.9 × 10−4 s−1 for 3′-dGMP, and ks = 8.1 M−2s−1 and ke = 3.6 × 10−4 s−1 for 5′-dGMP.

Scheme 3.

Kinetic Model for the oxidation of G by [PtIVCl4(dach)]

The A360 and A390 vs. time kinetic curves were processed by the DynaFit Software8 utilizing the kinetic model in Scheme 3. Figure 3 shows the close agreement between experimental and modeled absorbance vs. time. The data fit best when the initial PtII concentration was fixed at 0.4 % of initial PtIV. We assume that [PtIVCl4(dach)] contained 0.4 % of [PtIICl2(dach)] as an impurity.

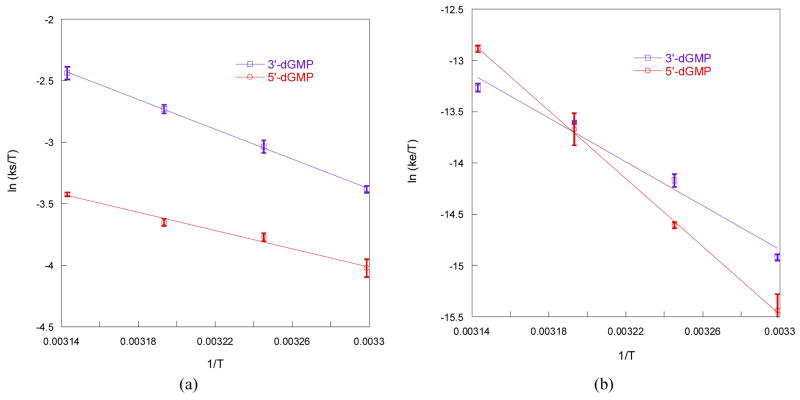

Rate constants determined over a temperature range of 30–45 °C are reported in Table 1. The activation parameters, ΔH‡ and ΔS‡, calculated from a linear least-squares fit to plots of ln (k/T) vs 1/T (Figure 4) are also reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Rate Constants and Activation Parameters for Reactions of [PtIVCl4(dach)] with 5′-dGMP and 3′-dGMP. [PtIV] = 5 mM, [PtII] = 0.02 mM and [dGMP] = 50 mM in 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.3

| ks (M−2s−1) | ΔH‡s, kJ mol−1 | ΔS‡s, J K −1 mol−1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 °C | 35 °C | 40 °C | 45 °C | |||

| 3′-dGMP | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 14.8 ± 0.6 | 20.4 ± 0.5 | 27.9 ± 1.5 | 50.4 ± 0.9 | −59.4 ± 1.3 |

| 5′-dGMP | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 8.1 ± 0.2 | 10.4 ± 0.2 | 30.7 ± 2.8 | −129.5 ± 16.8 |

| ke x 104 (s−1) | ΔH‡ e, kJ mol −1 | ΔS ‡ e, J K−1 mol−1 | ||||

| 30 °C | 35 °C | 40 °C | 45 °C | |||

| 3′-dGMP | 1.0 ± 0.02 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.06 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 88.8 ± 9.5 | −27.8 ± 5.0 |

| 5′-dGMP | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.04 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 8.1 ± 0.2 | 137.8 ± 2.9 | +128.8 ± 3.6 |

Figure 4.

Plot of (a) ln (ks/T) and (b) ln (ke/T) vs 1/T for the reaction of 5 mM [PtIVCl4(dach)] with 50 mM 5′-dGMP and 3′-dGMP.

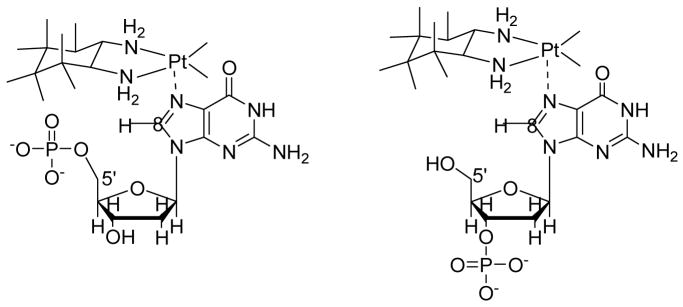

The substitution rate of 3′-dGMP is approximately twice as fast as that of 5′-dGMP at temperatures between 30 and 45 °C (ks35 = 14.8 M−2 s−1 and 7.1 M−2 s−1, respectively). The ΔH‡s of 3′-dGMP is approximately 70% bigger than that of 5′-dGMP (50.4 kJ mol−1 and 30.7 kJ mol-1). The enthalpic stabilization of 5′-dGMP may be due to the hydrogen bonding between the 5′-phosphate and the NH of the (dach) ligand.10 The 3′-phosphate is too far away to participate in hydrogen bonding with the NH of the ligand. The ΔS‡s of 3′-dGMP is significantly bigger than that of 5′-dGMP (−59.4 J K−1 mol−1 and −129.5 J K−1 mol−1, respectively), indicating that steric hindrance plays a major role in the substitution. The 5′-hydroxyl group exerts less steric hindrance than the 5′-phosphate group when the G binds to N7 (Chart 2). Dependence of a substitution on the steric hindrance of a carrier ligand has been well characterized by many researchers.5

Chart 2.

Steric hindrance between (dach) ligand and 5′- and 3′-dGMP.

3′-dGMP transfers electrons approximately twice as fast as 5′ ′-dGMP at 35 °C (2.2 × 10−4 s−1 and 1.4 × 10−4 s−1, respectively), but slightly slower at 45 °C (5.5 × 10−4 s−1 and 8.1 × 10−4 s−1, respectively). The ΔH‡e of 3′-dGMP is smaller than that of 5′-dGMP (88.8 kJ mol−1 and 137.8 kJ mol−1, respectively). The ΔS‡e of 3′-dGMP is much lower than that of 5′-dGMP (−27.8 J K−1 mol−1 and +128.8 J K−1 mol−1, respectively). At low temperature, ΔH‡e plays a major role in determining the rate constant. In order to initiate electron transfer, the nucleophilic group at the 5′-position should rotate to attack C8 as shown in Scheme 4. The lower ΔH‡e of 3′-dGMP indicates that the 5′-hydroxo group in 3′-dGMP has a lower rotational barrier than the 5′-phosphate in 5′-dGMP. The lower rotational barrier of Pt–N for 3′-

Scheme 4.

Internal electron transfer through cyclization.

GMP than for 5′-GMP is also reported by the Marzilli group.12 But above 40 °C, ΔS‡e plays a more important role. Cyclization and bond breaking are involved in the internal electron transfer, the former contributes a negative ΔS‡ and the latter a positive ΔS‡. Since the 5′-hydroxo group is much farther away from the C8 position than the 5′-phosphate group (Chart 2), 3′-dGMP must have a large negative ΔS‡ of cyclization, which is not compensated by the positive ΔS‡ of the bond breaking. However, since the 5′-phosphate in 5′-dGMP is close to C8, it may not have a large negative ΔS‡ of cyclization, and the positive ΔS‡ of bond breaking dominates in ΔS‡e, resulting in the positive Δ S‡ e.

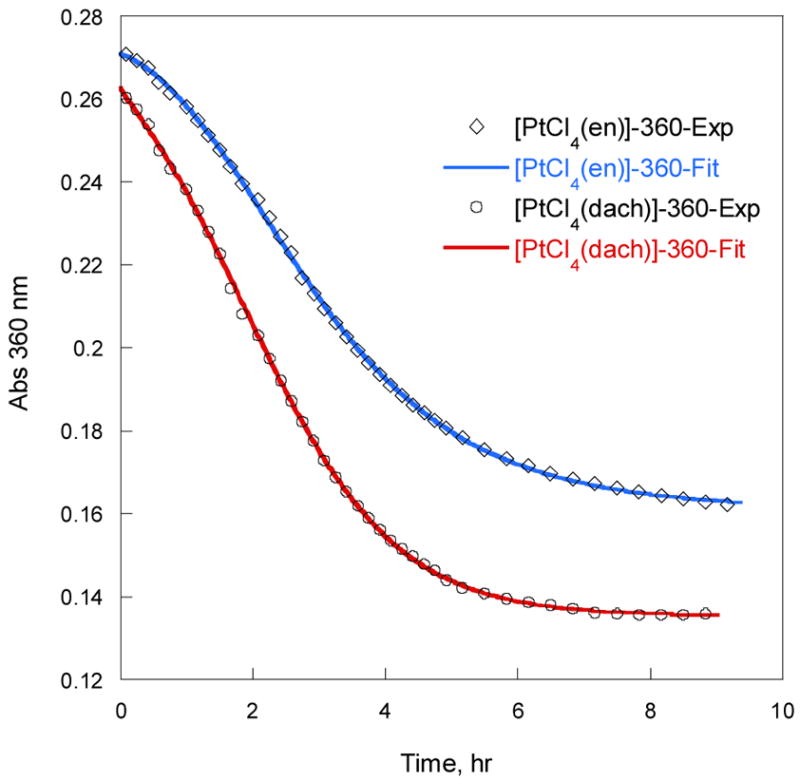

Comparison of [PtIVCl4(en) with [PtIVCl4(dach)]

The final G product of [PtIVCl4(en)]/5′-dGMP was the same as that of [PtIVCl4(dach)]/5′-dGMP, which was identified as 8-oxo-5′-dGMP by HPLC.2a The integration of the peaks reveals that the amount of 8-oxo-5′-dGMP generated by [PtIVCl4(en)] was approximately 70% of the amount by [PtIVCl4(dach)].

Figure 5 compares the time course of A360 of the [PtIVCl4(en)]/[PtIICl2(en)]/5′-dGMP reactions with [PtIVCl4(dach)]/[PtIICl2(dach)]/5′-dGMP at 50 °C. It clearly shows that [PtIVCl4(en)] reacts with 5′-dGMP in the same manner as [PtIVCl4(dach)] but at a different rate. The ks and ke of [PtIVCl4(en)] obtained by fitting A360 to eqs. (1) and (2) using DynaFit8 are 25.2 M−2s−1 and 1.5 × 10−4 s−1, respectively. The ks and ke of [PtIVCl4(dach)] are 11.1 M−2 s−1 and 14.2 × 10−4 s−1, respectively. The results indicate that [PtIVCl4(en)] is approximately twice faster in substitution but approximately ten times slower in electron transfer than [PtIVCl4(dach)]. The (en) is a smaller carrier ligand than (dach), which is responsible for the higher substitution rate of [PtIVCl4(en)]. But [PtIVCl4(en)] has lower reduction potential (Ec = −159 ± 5 mV vs Ag/AgCl) than [PtIVCl4(dach)] (Ec = −71 ± 10 mV vs Ag/AgCl), which explains the slow electron transfer rate of [PtIVCl4(en)].

Figure 5.

A360 vs. time of [PtIVCl4(en)]/[PtIICl2(en)] and [PtIVCl4(dach)]/[PtIICl2(dach)] with 5′-dGMP reactions at 50 °C. [PtIV] = 1 mM, [PtII] = 0.2 mM, [5′-dGMP] = 20 mM. 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.3. The solid lines are the fit to eqs. (1) and (2).

Conclusion

We have compared the substitution rate constant (ks) and the electron transfer rate constant (ke) in the redox reaction between PtIV and 3′- (or 5′-) dGMP using an autocatalytic kinetic model and DynaFit Software.8 Activation parameters were obtained from the rate constants at temperatures between 30 and 45 °C. The results show that 3′-dGMP substitutes faster than 5′-dGMP due to its small steric hindrance. In the electron transfer step, the reaction with 3′-dGMP is faster only at temperatures below 45 °C; the reaction with 3′-dGMP is enthalpically favorable, while the reaction with 5′-dGMP is entropically favorable. We have also shown that [PtIVCl4(en)] is faster than [PtIVCl4(dach)] in substitution due to its smaller carrier ligand, but slower in electron transfer due to its low reduction potential. The results reported here contribute to our understanding of platinum anticancer drugs and DNA reactions, which may be important in developing new anticancer therapies.

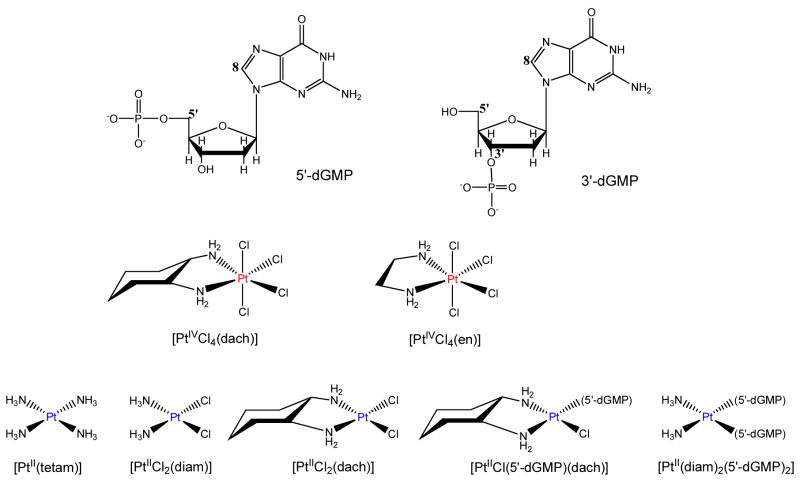

Chart 1.

Structures of the guanine derivatives and platinum complexes studied.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant CHE-0450060), the donors of Petroleum Research Fund administered by the American Chemical Society (Grant PRF-37873-B3), and the Vermont Genetics Network through the NIH Grant number P20 RR16462 from the INBRE program of the National Center for Research Resources..

References

- 1.(a) Fuertes MA, Alonso C, Perez JM. Chem Rev. 2003;103:645–662. doi: 10.1021/cr020010d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lippert B. Cisplatin: Chemistry and Biochemistry of a Leading Anticancer Drug. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 1999. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartley FR. Chemistry of the Platinum Group Metals, Recent Developments. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1993. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hall MD, Hambley TW. Coor Chem Rev. 2002;232:49–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Choi S, Cooley RB, Voutchkova A, Leung CH, Vastag L, Knowles DE. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1773–1781. doi: 10.1021/ja045194n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Choi S, Cooley RB, Hakemian AS, Larrabee YC, Bunt RC, Maupaus SD, Muller JG, Burrows CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:591–598. doi: 10.1021/ja038334m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Choi S, Delaney S, Orbai L, Padgett EJ, Hakemian AS. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:5481–5482. doi: 10.1021/ic015549t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Choi S, Mahalingaiah S, Delaney S, Neale NR, Masood S. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:1800–1805. doi: 10.1021/ic9809815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Choi S, Filotto C, Bisanzo M, Delaney S, Lagasee D, Whitworth JL, Jusko A, Li C, Wood NA, Willingham J, Schwenker A, Spaulding K. Inorg Chem. 1998;37:2500–2504. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Bancroft DP, Lepre CA, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6860–6871. [Google Scholar]; (b) McGowan G, Parsons S, Sadler P. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:7459–7467. doi: 10.1021/ic050763t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Arpalahti J, Lippert B. Inorg Chem. 1990;29:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) van Eldik R, Palmer DA, Kelm H. Inorg Chem. 1979;18:572–577. [Google Scholar]; (b) Inagaki K, Dijit FJ, Lempers ELM, Reedijk J. Inorg Chem. 1988;27:382–387. [Google Scholar]; (c) Summa N, Schiessl W, Puchta R, Hommes Nvan E, Eldik R. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:2948–2959. doi: 10.1021/ic051955r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wong HC, Coogab R, Intini FP, Natile G, Marzilli L. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:777–787. doi: 10.1021/ic980987u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Schmulling M, Lippert B, van Eldik R. Inorg Chem. 33:3276–3280. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kasparkova J, Marini V, Najajreh Y, Gibson D, Brabec V. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6321–32. doi: 10.1021/bi0342315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Williams KM, Rowan C, Mitchell J. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:1190–1196. doi: 10.1021/ic035212m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roat RM, Jerardi MJ, Kopay CB, Heat DC, Clark JA, DeMars JA, Weaver JM, Bezemer E, Reedijk J. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1997:3615–3621. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Lemma K, Shi T, Elding LI. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:1728–1734. doi: 10.1021/ic991351l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lemma K, Sargeson AM, Elding LI. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 2000:1167–1172. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lemma K, Berglund J, Farrell N, Elding LI. J Bio Inorg Chem. 2000;5:300–306. doi: 10.1007/pl00010658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Weaver EL, Bose RN. J Inorg Biochem. 2003;95:231–239. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(03)00136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bose RN, Weaver EL. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1997:1797–1799. [Google Scholar]; (c) Evans DJ, Green M. Inorg Chim Acta. 1987:183–185. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuzmic P. Anal Biochem. 1996;237:260–273. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Blatter EE, Vollano JF, Krishna BS, Babrowiak JC. Biochemistry. 1984;21:4817–4820. doi: 10.1021/bi00316a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ellis LT, Er HM, Hambley TW. Aust J Chem. 1995;48:793–806. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berbeners-Price SJ, Frey U, Ranford JD, Sadler PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:8649–8659. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Basolo F, Wilks PH, Pearson RG, Wilkins RG. J Inorg Nucl Chem. 1958;6:161. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mason WR. 1972;7:241–255. [Google Scholar]; (c) Summa GM, Scott BA. Inorg Chem. 1980;19:1079. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cox LT, Collins SB, Martin DS. J Inorg Nucl Chem. 1961;17:383. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Colonna G, Di Masi NG, Marzilli LG, Natile G. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:997–1005. doi: 10.1021/ic020506d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Carlone M, Fanizzi FP, Intini FP, Margiotta N, Larzilli LG, Natile G. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:634–641. doi: 10.1021/ic990517f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Carlone M, Marzilli LG, Natile G. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:584–592. doi: 10.1021/ic030236e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]