Abstract

Canine vector-borne diseases (CVBDs) are highly prevalent in Brazil and represent a challenge to veterinarians and public health workers, since some diseases are of great zoonotic potential. Dogs are affected by many protozoa (e.g., Babesia vogeli, Leishmania infantum, and Trypanosoma cruzi), bacteria (e.g., Anaplasma platys and Ehrlichia canis), and helminths (e.g., Dirofilaria immitis and Dipylidium caninum) that are transmitted by a diverse range of arthropod vectors, including ticks, fleas, lice, triatomines, mosquitoes, tabanids, and phlebotomine sand flies. This article focuses on several aspects (etiology, transmission, distribution, prevalence, risk factors, diagnosis, control, prevention, and public health significance) of CVBDs in Brazil and discusses research gaps to be addressed in future studies.

Background

Canine vector-borne diseases (CVBDs) constitute an important group of illnesses affecting dogs around the world. These diseases are caused by a diverse range of pathogens, which are transmitted to dogs by different arthropod vectors, including ticks, fleas, lice, triatomines, mosquitoes, tabanids, and phlebotomine sand flies.

CVBDs are historically endemic in tropical and subtropical regions and have increasingly been recognized, not only in traditionally endemic areas, but also in temperate regions [1]. This may be attributed to several factors, including the availability of improved diagnostic tools, higher public awareness about CVBDs, dog population dynamics, and environmental and climate changes [2], which directly influences the distribution of arthropod vectors and the diseases they transmit.

CVBDs have long been recognized in Brazil [3]. At the beginning of the 21st century, CVBDs are prevalent in all regions of the country and some of them have increasingly been recognized in previously free areas, as it is the case of canine leishmaniasis in São Paulo, Southeast Brazil [4-11]. Despite their recognized importance, many aspects concerning epidemiology and public health significance of CVBDs in Brazil are still poorly known and data have not been comprehensively discussed.

This article summarizes several aspects (etiology, transmission, distribution, prevalence, risk factors, diagnosis, control, prevention, and public health significance) of CVBDs in Brazil and discusses research gaps to be addressed in future studies.

Protozoal diseases

Canine babesiosis

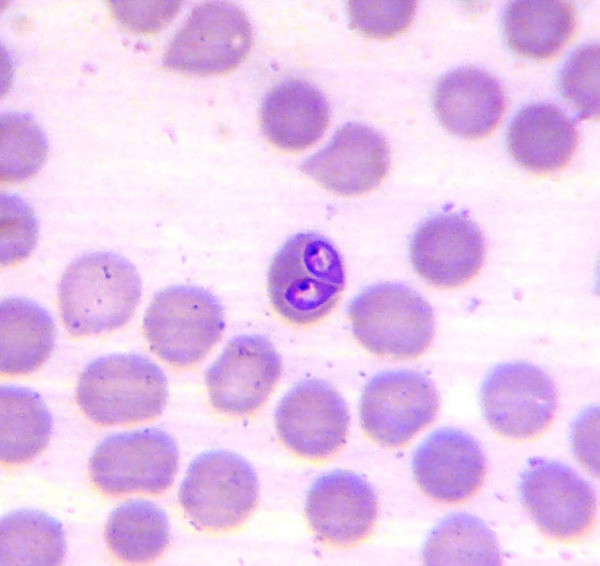

Canine babesiosis has been recognized in Brazil since the beginning of the 20th century [12]. This disease is caused by Babesia vogeli (= Babesia canis vogeli) (Piroplasmida: Babesiidae) (Fig. 1), which has recently been molecularly characterized in Brazil [13]. Cases of Babesia gibsoni infection in Brazilian dogs have also been reported [14]. The only proven vector of B. vogeli in Brazil is Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Fig. 2), which is also the suspected vector of B. gibsoni [15].

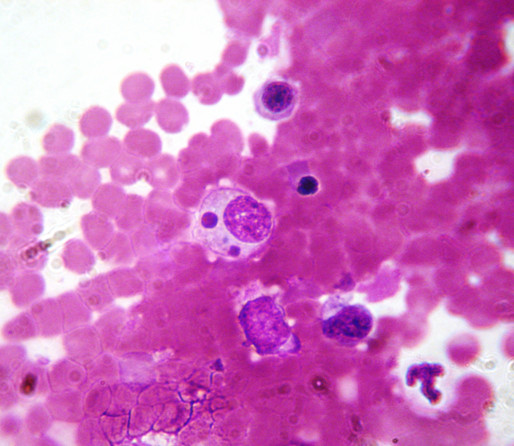

Figure 1.

Babesia vogeli. Two Babesia sp. trophozoites in a blood smear from a naturally infected dog.

Figure 2.

Rhipicephalus sanguineus. A dog heavily infested by Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks.

Canine babesiosis is prevalent in virtually all Brazilian regions [12,16-24]. The prevalence of infection ranges from 35.7 [24] to 66.9% [16] in serological surveys and from 1.9 [23] to 42% [21] by cytology on blood smears. The incidence of disease seems to be higher among adult dogs [24], although young dogs are also highly susceptible to infection [22]. Apparently, there are no breed or sex predilections [16,21,24-26].

The diagnosis of canine babesiosis is usually based on the presence of suggestive clinical signs (e.g., apathy, fever, anorexia, weigh loss, pale mucous membranes, and jaundice) and patient history. The infection by Babesia spp. is confirmed by the examination of Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smears. A detailed review of all aspects, including diagnosis and treatment, of canine babesiosis in Brazil can be found elsewhere [22].

Canine leishmaniasis

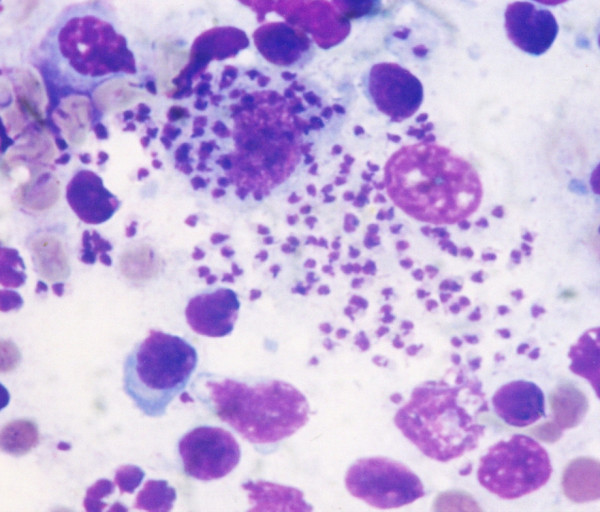

Canine leishmaniasis was firstly recognized in Brazil during the 1930s [27]. This disease is mainly caused by Leishmania infantum (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) (Fig. 3), sometimes referred to as Leishmania chagasi or Leishmania infantum chagasi [28]. Infection by other Leishmania species (e.g., Leishmania amazonensis) have also been reported [7,10] and cases of co-infection by two species (e.g., L. infantum and Leishmania braziliensis) as well [29]. The main vector of L. infantum in Brazil is Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae). Other modes of transmission, including by Rh. sanguineus ticks, are suspected to occur [30,31], particularly in foci where suitable phlebotomine sand fly vectors are absent (e.g., Recife, Northeast Brazil) [32]. The vectors of L. amazonensis and L. braziliensis vary from region to region and several species may eventually be involved, including Lutzomyia whitmani (Fig. 4) and Lutzomyia intermedia (reviewed in [33]).

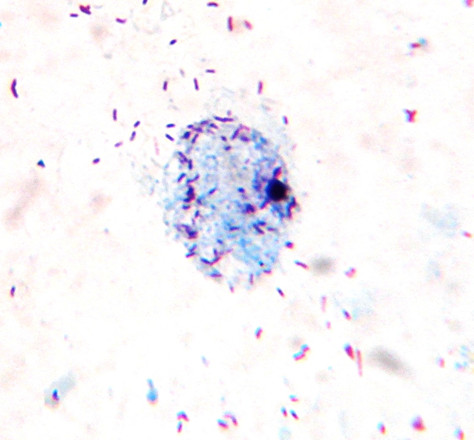

Figure 3.

Leishmania infantum. Several Leishmania infantum amastigotes in a bone marrow smear from a naturally infected dog.

Figure 4.

Lutzomyia whitmani. External genitalia of a male of Lutzomyia whitmani, which contains structures of major taxonomic importance.

Canine visceral leishmaniasis by L. infantum is endemic in all Brazilian regions [34-47], except in South where the disease is seldom recognized [44,48,49]. Canine cutaneous leishmaniasis by L. braziliensis is also prevalent in all regions [7,10,38,50-58], except in Center-West. The only two cases of L. amazonensis infection in dogs reported so far were diagnosed in Southeast Brazil [10]. The prevalence of Leishmania spp. infection in dogs varies widely [38,47,59,60] and may be as high as 67% in highly endemic foci [61]. Risk factors associated with canine leishmaniasis have extensively been studied in Brazil. There appears to be no sex predilection [35,60]. Although the prevalence of infection is often higher among males [47], this seems to be a matter of exposition rather than sex-related susceptibility. The prevalence is also higher in young dogs [47]. Some breeds (e.g., boxer and cocker spaniel) are apparently more susceptible to L. infantum infection [60]. Short-furred dogs are at a higher risk of infection [60] and this has been attributed to the fact that their short-hair makes them more exposed to phlebotomine sand fly bites.

The diagnosis of canine leishmaniasis is based on the presence of suggestive clinical signs (e.g., weight loss, dermatitis, hair loss, mouth and skin ulcers, enlarged lymph nodes, onychogryphosis, and conjunctivitis) (Fig. 5) and on a positive serological response to Leishmania antigens [47,62]. Detailed information on several aspects of canine leishmaniasis, including diagnosis and treatment, can be found elsewhere [31,63,64].

Figure 5.

Canine visceral leishmaniasis. A dog displaying a typical clinical picture of visceral leishmaniasis.

The treatment of canine leishmaniasis is not routinely practiced in Brazil. Until the middle of the 1980s, most attempts to treat Brazilian dogs affected by leishmaniasis were unsuccessful [65]. Nowadays, there is scientific evidence supporting the treatment of canine leishmaniasis in Brazil [66-69]. However, although the available protocols are effective in promoting clinical improvement, a parasitological cure is seldom achieved [66-71]. Hence, considering the importance of dogs in the epidemiology of zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply have recently prohibited the treatment of canine visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil [see Addendum].

Canine hepatozoonosis

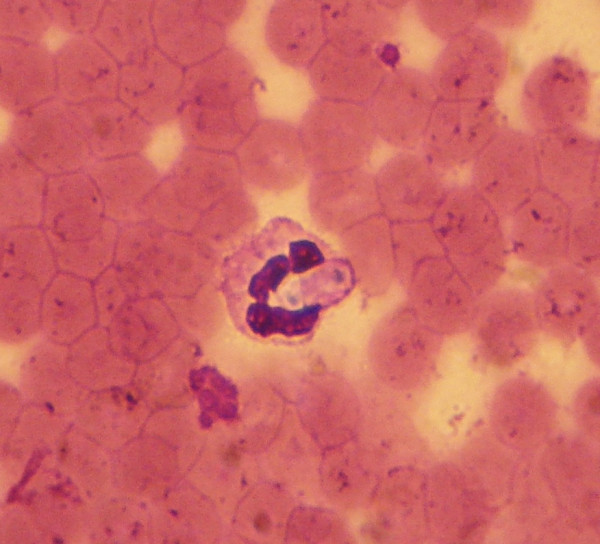

Canine hepatozoonosis was firstly diagnosed in Brazil during the 1970s [72]. This disease is caused by Hepatozoon canis (Apicomplexa: Hepatozoidae) (Fig. 6), which has recently been molecularly characterized in Brazil [73-75]. Dogs become infected by ingestion of a tick containing mature H. canis oocysts. Ticks involved in the transmission of H. canis in Brazil include some Amblyomma species, particularly Amblyomma aureolatum, Amblyomma ovale (Fig. 7), and Amblyomma cajennense [76-78]. Rhipicephalus sanguineus, which is a known vector of H. canis in the Old World, may also play a role in the transmission of this pathogen in Brazil.

Figure 6.

Hepatozoon canis. A gamont of Hepatozoon canis in a blood smear from a naturally infected dog.

Figure 7.

Amblyomma ovale. A female of Amblyomma ovale firmly attached to and feeding on a dog.

Canine hepatozoonosis is prevalent in Center-West, Northeast, South, Southeast [72-82], and much probably in the North region. The prevalence of infection may be as high as 39% in some rural areas [76]. Little is known about the risk factors associated with H. canis infection in Brazil. The infection is more prevalent in rural areas [76], where dogs are more exposed to Amblyomma ticks. However, this association is not fully understood, because dogs from urban areas are highly exposed to Rh. sanguineus [83], a major vector of H. canis in the Old World [84].

The diagnosis of canine hepatozoonosis is based on the presence of suggestive clinical signs (e.g., apathy, anorexia, pale mucous membranes, fever, weight loss, diarrhoea, vomit, and muscle pain) and on the observation of H. canis gamonts in leucocytes in Giemsa-stained blood smears [79,84-87]; the sensitivity is higher if peripheral blood is used [78]. More information on diagnosis and treatment of canine hepatozoonosis can be found elsewhere [84,86].

Canine trypanosomiasis

Canine trypanosomiasis has been studied in Brazil since the beginning of the 20th century [88]. This disease is caused by protozoa of the genus Trypanosoma (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) and has sporadically been recognized in Brazil. Trypanosoma species known to infect dogs in Brazil are Trypanosoma evansi [89-96], Trypanosoma cruzi [97-100], and possibly Trypanosoma rangeli [101], the latter species is normally nonpathogenic.

The vectors of T. cruzi (a stercorarian species) are triatomines of the genera Panstrongylus, Rhodnius, and Triatoma (Hemiptera: Triatominae). Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks feed on dogs infected by T. cruzi can acquire the infection [102], but there is no evidence supporting the development and subsequent transmission to naïve dogs. Trypanosoma cruzi infection in dogs is prevalent in all regions, except in South [103]. In areas where American trypanosomiasis (or Chagas disease) is endemic, it is estimated that around 15–50% of the dogs are exposed to T. cruzi infection [97-100,104,105]. Clinically, the infection is of minor significance; that is, infected dogs are often asymptomatic carriers. In an experimental model, only sporadic febrile episodes were noted during the first weeks post inoculation [106]. Some dogs developed chronic focal and discrete myocarditis, which was only noticed during necropsy [106].

The vectors of T. evansi (a salivarian species) are hematophagous flies of the genera Tabanus (Diptera: Tabanidae) and Stomoxys (Diptera: Muscidae) (Fig. 8). Trypanosoma evansi infection in dogs is found predominately in Center-West and South regions [89-96,107,108]. In Mato Grosso (Center-West Brazil), for instance, the prevalence of T. evansi infection is serologically estimated to be around 30% [90]. Dogs are regarded as efficient reservoirs of T. evansi, which is the causative agent of a severe disease affecting horses, commonly known as mal de cadeiras or surra. The infection in dogs is also severe and potentially fatal [93]. Clinical signs include edema of the hind limbs, anorexia, apathy, dehydration, pale mucous membranes, fever, and weight loss [93,108-110].

Figure 8.

Stomoxys calcitrans. Several stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans) feeding on a dog.

Vectors of T. rangeli are triatomines of the genus Rodnius. While T. cruzi is transmitted through the feces of triatomines, T. rangeli is can be transmitted through both feces and saliva. Trypanosoma rangeli is widely spread in Brazil and has been found on a large number of hosts, including marsupials, rodents, and humans [101,111-114]. While nonpathogenic neither to dogs nor to humans, T. rangeli can be confounded with T. cruzi, which poses a challenge for the diagnosis of Chagas diseases, particularly in areas where both species are endemic. The distinction between T. rangeli and T. cruzi can be done by several biological, immunological, biochemical and molecular assays. The characteristic biological behavior in the invertebrate host is considered the best method for their differentiation [115].

Nambiuvú

Nambiuvú (in English, bloody ears) or peste de sangue (bleeding plague) was firstly recognized in Brazil in 1908 [116]. This little known disease is caused by Rangelia vitalli (Piroplasmorida), a protozoan whose current taxonomic position is uncertain. The infection is thought to be transmitted by ticks [117]. Cases of Nambiuvú have been recognized in Center-West, South, and Southeast regions [117-120]. The diagnosis of Nambiuvú is based on the presence of suggestive clinical signs (e.g., anemia, jaundice, fever, splenomegaly, and persistent bleeding from the nose, oral cavity, and tips, margins and outer surface of the pinnae) (Fig. 9) and on the observation of the parasites within endothelial cells of blood capillaries in necropsy samples. Recent information on several aspects of Nambiuvú can be found elsewhere [117,121].

Figure 9.

A dog with clinical signs of the so-called Nambiuvú. Massive bleeding from the skin covering the dorsal surface of the pinna.

Bacterial diseases

Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis

Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis was firstly recognized in Brazil in the 1970s [122]. This disease is caused by Ehrlichia canis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) (Fig. 10), which was firstly isolated in Brazil in 2002 [123]. The agent of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis is well characterized in Brazil [124-128], where it is transmitted by Rh. sanguineus [124]. Other Ehrlichia species found in Brazil – e.g., Ehrlichia chaffeensis; [129] – are also suspected to infect dogs. In fact, there is serological evidence of E. chaffeensis infection in Brazilian dogs [130].

Figure 10.

Ehrlichia canis. A morula of Ehrlichia canis in a bone marrow smear from a naturally infected dog.

Canine ehrlichiosis is prevalent in virtually all regions of Brazil [24,124-127,131,132]. This disease affects around 20–30% of the dogs referred to veterinary clinics and hospitals in Brazil [24,124,131], but the prevalence of infection vary widely from region to region [23,76,126,128,131-135]. The prevalence of infection can be as high as 46.7% in asymptomatic [128] and 78% in symptomatic dogs [132]. The risk of E. canis infection is higher for dogs that live in houses when compared to dogs living in apartments [23]. This is expected because dogs that live in houses with backyards are theoretically more exposed to ticks than those living in apartments. Seroepidemiological studies revealed that male adult dogs are more likely to present antibodies to E. canis, particularly those infested by ticks [24,134].

The diagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis is usually based on clinical signs (e.g., fever, pale mucous membranes, apathy, anorexia, lymphnode enlargement, and weight loss) and on the observation of E. canis morulae in Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smears. More information on diagnosis and treatment of canine ehrlichiosis can be found elsewhere [136].

Canine anaplasmosis

Canine anaplasmosis is caused by Anaplasma platys (formerly Ehrlichia platys) (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) and has been recognized sporadically in Brazil. There are different A. platys strains circulating in Brazilian dogs, as revealed by analysis of partial sequences of the 16S rRNA gene [137]. The vector of A. platys is still unknown or unproven. Ticks of various genera (e.g., Rhipicephalus, Dermacentor, and Ixodes) have been found naturally infected by A. platys around the world [138-142]. The suspected vector of A. platys in Brazil is Rh. sanguineus.

Canine anaplasmosis has been found in all regions of Brazil, although few cases have been formally published in the literature [124,127,143-145]. The prevalence of A. platys infection ranges from 10.3 [146] to 18.8% [145]. Little is known about risk factors associated with canine anaplasmosis in Brazil. The infection by A. platys is seldom associated with clinical disease, except in cases of co-infection with other organisms (e.g., E. canis and B. vogeli), which is common in Brazil [19,21,127,134]. Typically, dogs infected by A. platys display only a cyclic thrombocytopenia, but no hemorrhagic events are noted. The laboratory diagnosis is based on the observation of A. platys inclusions in platelets in peripheral blood smears stained with ordinary hematological staining methods. Serological studies have never been performed and molecular techniques are currently restricted to research.

Canine Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Canine Rocky Mountain spotted fever is caused by Rickettsia rickettsii (Fig. 11) and has been associated with significant morbidity and occasional mortality in the United States [147,148]. Serological surveys conducted in Brazil have shown that dogs from some Rocky Mountain spotted fever-endemic areas (e.g., Minas Gerais and São Paulo) are exposed to R. rickettsii infection [129,149-154]. The vectors of R. rickettsii are Amblyomma ticks, mainly Am. cajennense [155] (Fig. 12) and Am. aureolatum [156]. Additionally, Rh. sanguineus ticks have the potential to be involved in the R. rickettsii transmission cycle in areas other than Mexico and United States, including Brazil [157]. Serological surveys in Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo, Rondônia, and São Paulo revealed that the prevalence of anti-R. rickettsii antibodies in dogs ranges from 4.1 to 64% [129,149-154,158]. However, it is difficult to estimate the actual prevalence of R. rickettsii infection in dogs using serological tests, because of their low specificity [157].

Figure 11.

Rickettsia rickettsii. Rickettsia rickettsii growing in Vero cells.

Figure 12.

Amblyomma cajennense. Amblyomma cajennense ticks feeding on a horse.

Little is known about the risk factors associated with R. rickettsii infection in Brazilian dogs. In a study conducted in São Paulo, the proportion of dogs positive to anti-R. rickettsii antibodies increased with age [158]. Although there is no information about clinical cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in dogs in Brazil, veterinarians working in areas where human cases have been reported must consider the possibility of this disease to request laboratory tests that will allow a proper diagnosis.

Canine haemobartonellosis

Canine haemobartonellosis has been sporadically recognized in Brazil, but little is known about this disease in this country, because few reports have been formally published in the literature. This disease is caused by Mycoplasma haemocanis (formerly Haemobartonella canis) (Mycoplasmatales: Mycoplasmataceae), which is transmitted by Rh. sanguineus [159]. Mycoplasma haemocanis infection in dogs has been recognized in South and Southeast Brazil [17,144,160-162]. Clinical disease in immunocompetent animals is uncommon. On the other hand, immunosuppressed dogs (e.g., splenectomized dogs) are particularly susceptible to infection [161,163].

Clinical signs include pale mucous membrane, weight loss, apathy, anorexia, and fever [164]. The diagnosis of M. haemocanis infection is based on microscopic examination of blood smears stained with ordinary hematological staining techniques. Serological and molecular assays have also been used [164].

Canine borreliosis

A Lyme-like illness has been recognized in humans in Brazil since 1989 [165], although the true identity of the causative agent has not yet been determined. Serological surveys conducted in Southeast Brazil confirmed that dogs are often exposed to infection by Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato). Borrelia-like spirochetes have been detected in Ixodes ticks in the State of São Paulo [166], but the possible vectors of B. burgdorferi s. l. in Brazil are largely unknown. Amblyomma ticks are also suspected to be involved in transmission [167].

The prevalence of anti-B. burgdorferi s. l. antibodies in Brazilian dogs ranges from less than 1 up to 20% [130,132,168,169]. The infection in dogs is usually asymptomatic and there appears to be no correlation between seropositivity and sex or age of the animals [169]. As expected, the seropositivity correlates with history of previous contact with ticks [169]. At present, there is no information about the treatment of dogs with suspected B. burgdorferi s. l. infection in Brazil.

Helminthiasis (heartworm and tapeworm)

Canine dirofilariasis

Canine heartworm was firstly recognized in Brazil in 1878 [3]. The disease is caused by Dirofilaria immitis (Nematoda: Onchocercidae), which is transmitted by many mosquito species. Aedes scapularis and Aedes taeniorhynchus are implicated as the primary vectors, while Culex quinquefasciatus is a secondary vector [170-174]. Another filarid nematode commonly found infecting dogs in Brazil is Acanthocheilonema reconditum (formerly Dipetalonema reconditum) (Nematoda: Onchocercidae), whose intermediate hosts are fleas (Ctenocephalides canis and Ctenocephalides felis) (Fig. 13) and lice (Heterodoxus spiniger and Trichodectes canis) [175,176]. Acanthocheilonema reconditum infection usually causes no clinical signs in dogs. Despite this, it is important to distinguish the microfilaria of A. reconditum from that of D. immitis, as these filarid nematodes are often found in sympatry.

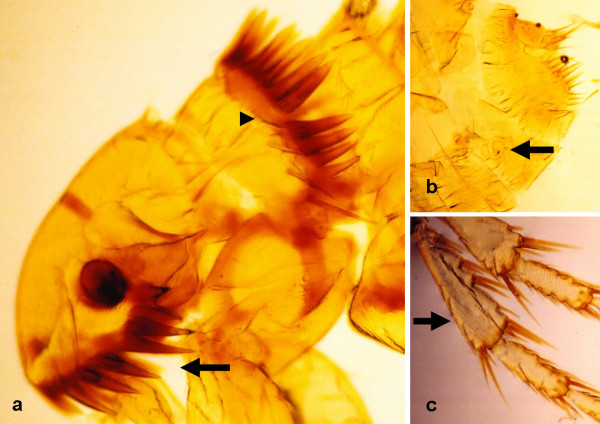

Figure 13.

Ctenocephalides felis female. (a) Flea's head, exhibiting the characteristic genal (arrow) and pronotal (arrowhead) combs. (b) Spermatheca (arrow). (c) Chaetotaxy of tibia (arrow) of leg III.

Dirofilaria immitis is prevalent in virtually all regions of Brazil [3,172,177-185]. The prevalence of D. immitis infection in dogs varies widely and can be higher than 60% in highly endemic foci [185]. The countrywide prevalence has decreased from 7.9% in 1988 to 2% in 2001 [186]. The possible reasons for this decrease include the reduction of transmission as a result of effective chemoprophylaxis and/or reduction of microfilaremic dog populations due to the off-label use of injectable ivermectin [187]. The risk of D. immitis infection is grater in dogs living in coastal regions [170,172,182,187] and in dogs older than two years [185]. Apparently there is no sex or breed predisposition [172,182]. In some areas, the prevalence of infection is higher among males [177,185], although this is likely to be a matter of exposure rather than sex-related susceptibility. Likewise, the prevalence of infection seems to be higher among mixed-breed dogs [188].

The diagnosis of canine heartworm is based on clinical signs (e.g., coughing, exercise intolerance, dyspnea, weight loss, cyanosis, hemoptysis, syncope, epistaxis, and ascites). The infection is confirmed by the observation of microfilariae in blood samples using the modified Knott's test or the detection of antigens produced by adult heartworms using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits [189].

Dipylidiasis (tapeworm infection)

Dipylidiasis is caused by Dipylidium caninum (Cestoda: Dipylidiidae), whose intermediate hosts include fleas (C. felis and C. canis) and lice (T. canis and H. spiniger). Dogs become infected by ingestion of intermediate hosts containing infective cysticercoids (i. e., the adult tapeworm encysted in the intestinal wall of an intermediate host) [190]. In a recent study on endosymbionts of C. felis felis collected from dogs in Minas Gerais, of 1,500 fleas examined, six (0.4%) were infested by D. caninum [191]. Not surprisingly, the infestation by D. caninum in dogs (and also in cats) is commonly found in all regions of Brazil [192-198]. The infestation is usually asymptomatic. Some dogs may be seen scooting or dragging the rear end across the floor. This behavior is a consequence of the intense perianal pruritus caused by the rice grain-like proglottids, which can be eventually seen crawling around the anus.

Control and prevention of CVBDs in Brazil

Vaccination

At present, only two CVBDs are preventable by vaccination in Brazil. A vaccine (Leishmune, Fort Dodge Animal Health Brazil) against canine visceral leishmaniasis was recently licensed in Brazil [199]. This vaccine is only recommended for healthy, seronegative dogs at the minimum age of four months. The vaccine is well tolerated, although some dogs display transient mild adverse events (e.g., pain, anorexia, apathy, local swelling reactions, vomit, and diarrhea) [200]. Its efficacy is around 80% [43]. However, it is important to state that this vaccine protects dogs against the disease (i. e., appearance of clinical signs), but not against L. infantum infection [199].

Until recently, there was no vaccine against canine babesiosis in Brazil [22]. A vaccine (Nobivac® Piro, Intervet Brazil) was recently licensed for commercialization in Brazil, but no information about efficacy and safety of this vaccine in preventing canine babesiosis in Brazil is currently available.

Chemoprophylaxis

The chemoprophylaxis of canine heartworm is usually undertaken in Brazil, using different microfilaricides, such as ivermectin, milbemycin oxime, and selamectin [189]. The chemoprophylaxis of canine babesiosis has been recommended in Brazil [22]. Imidocarb can protect dogs from B. canis infection for 2–6 weeks [201], whereas doxycycline is effective in preventing clinical disease, but not infection [202].

Vector control

Vector control is the only effective measure for the control of most CVBDs in Brazil. The strategies currently used for the control of ticks in Brazil have recently been reviewed elsewhere [22,203]. The control of vectors other than ticks (i. e., fleas, lice, mosquitoes, triatomines, and phlebotomine sand flies) is performed by using insecticides under different formulations (pour-on, spot on, spray, etc.). The use of insecticide-impregnated collars limits the exposure of dogs to phlebotomine sand flies. However, it has been demonstrated that the impact of such intervention is dependent on collar coverage and loss rate [204]. Moreover, experience shows that this approach is of limited impact, mainly because most dog owners living in endemic areas cannot afford the costs such collars.

Other control measures

While not universally accepted, the culling of dogs positive to anti-Leishmania antibodies is still practiced in Brazil [70,72]. This control measure has been subject of intense, ongoing debate in Brazil. Many dog owners, veterinarians, and non-governmental organizations have opposed the culling of seropositive dogs, both for ethical reasons and due to the lack of scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of this strategy.

From 1990 to 1994, more than 4.5 million dogs were screened and more than 80,000 were culled in Brazil [205]. In the same period, there was an increase of almost 100% in the incidence of human visceral leishmaniasis [205]. Actually, China is probably the only country where the culling of seropositive dogs seems to have been effective [206]. The possible reasons for the failure of the culling of seropositive dogs in Brazil include: high incidence of infection, limited sensitivity and specificity of available diagnostic methods, the time delays between diagnosis and culling, rapid replacement of culled dogs by susceptible puppies or already infected dogs, and owner's unwillingness to give up asymptomatic seropositive dogs [11,70,206,207]. A recent study conducted in Southeast Brazil suggests that the dog culling as a control measure for human visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil should be re-evaluated [11].

CVBDs from the public health standpoint

CVBDs constitute a group of diseases of great interest because some vector-borne pathogens affecting dogs in Brazil (e.g., L. infantum,T. cruzi, and E. canis) are potentially zoonotic (see Tables 1, 2, and 3). Despite this, in some instances, there is little research-based evidence supporting the role of dogs in the transmission to these pathogens to humans in Brazil.

Table 1.

Vector-borne protozoa affecting dogs in Brazil.

| Agent | Vector(s) | Distribution a | Zoonotic potential |

| Babesia vogeli |

Rhipicephalus sanguineus |

Center-West, North, Northeast, South, Southeast |

Yes (but low) |

| Babesia gibsoni | Rh. sanguineus? | Southeast, South | No |

| Hepatozoon canis |

Amblyomma spp., Rh. sanguineus |

Center-West, Northeast, South, Southeast |

No |

|

Leishmania amazonensis |

Lutzomyia spp. | Southeast | Yes b |

|

Leishmania braziliensis |

Lutzomyia spp. | North, Northeast, South, Southeast, |

Yes b |

| Leishmania infantum |

Lutzomyia longipalpis, Lutzomyia spp. |

Center-West, North, Northeast, South, Southeast |

Yes |

| Rangelia vitalli |

Amblyomma spp.?, Rh. sanguineus? |

Center-West, South, Southeast |

No |

| Trypanosoma cruzi |

Panstrongylus spp., Triatoma spp., Rhodnius spp. |

Center-West, North, Northeast, South, Southeast |

Yes |

| Trypanosoma evansi |

Tabanus spp., Stomoxys spp. |

Center-West, South | No |

a Includes some reports not formally published.

b Dogs are unlikely to be important reservoir hosts for human infection.

Table 2.

Vector-borne bacteria affecting dogs in Brazil.

| Agent | Vector(s) | Distribution a | Zoonotic potential |

| Anaplasma platys |

Rhipicephalus sanguineus? |

Center-West, North, Northeast, South, Southeast |

Yes (but low) |

| Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. |

Amblyomma spp.?, Rh. sanguineus? |

Center-West, Northeast, Southeast |

Yes b |

| Ehrlichia canis | Rh. sanguineus | Center-West, North, Northeast, South, Southeast |

Yes |

| Mycoplasma haemocanis | Rh. sanguineus | South, Southeast | No |

| Rickettsia rickettsii |

Amblyomma spp., Rh . sanguineus? |

Southeast | Yes b |

a Includes some reports not formally published.

b Dogs are unlikely to be important reservoir hosts for human infection.

Table 3.

Vector-borne helminths affecting dogs in Brazil.

| Agent | Vector(s) | Distribution a | Zoonotic potential |

| Acanthocheilonema reconditum |

Ctenocephalides spp., Heterodoxus spiniger, Trichodectes canis |

Center-West, Northeast, South, Southeast |

Yes (but low) |

| Dipylidium caninum |

Ctenocephalides spp., H. spiniger, T. canis |

Center-West, North, Northeast, South, Southeast |

Yes |

| Dirofilaria immitis |

Aedes spp., Culex spp. |

Center-West, North, Northeast, South, Southeast |

Yes |

a Includes some reports not formally published.

Dogs are implicated as important reservoirs of L. infantum in Brazil [206-211]. It is interesting to note that in some areas a high proportion of dogs are exposed to L. infantum infection [47], but human cases of visceral leishmaniasis are only sporadically notified [210]. In these areas, the low incidence of visceral leishmaniasis may be because of the difficulties in diagnosing and notifying the human cases [207,210], but it also indicate that the role of dogs in the epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis may vary from region to region [211].

Near a century after its discovery, Chagas disease is still a serious public health concern in Brazil. Dogs are considered to be an efficient source of T. cruzi infection and are thought to play a role in the peridomestic transmission cycle [212,213]. However, Southern Cone countries (e.g., Brazil) have experienced significant changes in the epidemiology of Chagas disease in recent years [214]. New studies to understand the current role of dogs in the cycle of transmission of T. cruzi in Brazil are needed.

Human ehrlichiosis is an emerging zoonosis that has been suspected to occur in Brazil since 2004 [215,216]. The suspected causative agent is E. chaffeensis [216], but tick vectors are completely unknown. Cases of natural infection by E. chaffeensis in dogs are suspected to occur in Brazil [129], but this has not yet been confirmed [126]. Cases of human ehrlichiosis caused by E. canis infection have been reported in Venezuela [217]. This raises a number of questions about the risk of E. canis infection in humans in Brazil as the main vector (i. e., Rh. sanguineus) of this rickettsial agent is already known to parasitize humans in this country [218,219]. Further molecular studies are urgently needed to characterize the cases of human ehrlichiosis in Brazil.

Human pulmonary dirofilariasis, a zoonosis that has been diagnosed in Brazil since 1887 [220], has been reported in Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Santa Catarina [179,220-227], where the prevalence of D. immitis infection in dogs is moderate to high [183,186]. Cases of human dipylidiasis have also been reported in Brazil [228-230]. Dogs play a major role in the transmission of D. caninum for humans, and thus must be periodically evaluated for the presence of gastrointestinal helminths and treated accordingly.

Little is known about human babesiosis in Brazil, where clinical cases of are seldom recognized [231-233]. As B. canis is rarely involved in cases of babesiosis in humans [234], dogs are unlikely to play a role in the epidemiology of human babesiosis in Brazil. Although dogs are also unlikely reservoirs of R. rickettsii [157], they may play a role in bringing ticks to human dwellings, particularly if ticks like Am. aureolatum and Rh. sanguineus are involved in the transmission.

Research gaps

Rhipicephalus sanguineus is potentially involved in the transmission of at least nine pathogens affecting dogs in Brazil. Despite this, little is known of the relationship between the ecology of Rh. sanguineus and the dynamics of CVBDs in Brazil. Further research is needed to clarify the role of Rh. sanguineus in the transmission of A. plays, B. gibsoni, H. canis, R. rickettsii, and L. infantum in Brazil.

Considering that dogs and humans live in close contact and that both dogs and humans are susceptible to infection by L. infantum and L. braziliensis, it is reasonable to imagine that in areas where dogs are exposed to these pathogens, humans are exposed as well. However, the finding of a dog infected by a given Leishmania species should be analyzed carefully to avoid misinterpretation. While the role of dogs in L. infantum transmission is well known, their role as reservoirs of other Leishmania species is probably minor [208]. The epidemiology of the leishmaniases is complex and varies from region to region and even within each region. The pattern of transmission of Leishmania parasites is intimately linked to the behavior of hosts and vectors involved. Local studies are crucial to understand the dynamics of transmission and to provide information for the establishment of vector control programs.

Most information on CVBDs in Brazil has been informally presented in scientific meetings, which makes it difficult to access the actual distribution and prevalence of these diseases across the different geographical regions of the country. For instance, only five CVBDs have been formally reported to occur in the North region, while 13 CVBDs have been recognized in Southeast Brazil. Indeed, this situation reflects the limited number of studies on CVBDs carried out in North in comparison with Southeast Brazil, where there is a large number of researchers working in this field. Further studies to access the countrywide distribution and prevalence of CVBDs should be encouraged. It is also important to evaluate the impact of environmental changes and human behavior on the prevalence and zoonotic potential of CVBDs in Brazil. CVBDs are likely influenced by climate variations and environmental changes. Also, the zoonotic potential of these diseases is probably greater in remote areas where the access to education and healthcare services is limited.

Co-infection by vector-borne pathogens is a common condition among Brazilian dogs [19,21,29,94,127,134,235]. This is expected because these pathogens often share the same arthropod vector. The occurrence of mixed infections is of great practical importance. Just to give an example, the use of serological tests with low specificity to access L. infantum infection may lead to an unnecessary culling of dogs infected by L. braziliensis or even by T. cruzi [236,237], in areas where both species occur. The use of contemporary techniques to distinguish the species of Leishmania infecting dogs [7] is highly desirable, particularly where L. infantum and L. braziliensis occur in sympatry. The burden of co-infections in Brazilian dogs should be investigated and better molecular tools should be developed to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis.

Conclusion

In this review, it became clear that CVBDs in Brazil should be faced as a priority by public health authorities. Certain vector-borne pathogens infecting dogs in Brazil are of great significance for human health, as it is the case of L. infantum and T. cruzi. In this scenario, veterinarians play a key role in providing information to owners about what they should do to reduce the risk of infection by zoonotic vector-borne pathogens in their dogs and in themselves.

CVBDs are prevalent in all geographical regions of Brazil and have been increasingly recognized in recent years. In part, this is a result of the improvements achieved in terms of diagnostic tools. On the other hand, factors such as deforestation, rapid urbanization, climate changes, and the indiscriminate use of chemicals may cause a significant impact on the dispersion of arthropod vectors and on the incidence of CVBDs. The impact of such factors on CVBDs in Brazil has not yet been fully addressed and deserves further research.

Today, the use of molecular biology techniques is contributing to the knowledge on the etiology and epidemiology of CVBDs in Brazil. A better understanding about the ecology of the arthropods involved in the transmission of pathogens to dogs in Brazil is essential to reduce the burden of CVBDs, whose magnitude is probably much greater than is actually recognized.

Addendum

After this manuscript was submitted, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply have published an ordinance prohibiting the treatment of canine leishmaniasis in Brazil [238]. Indeed, this ordinance will enhance the debate around the treatment of canine leishmaniasis in Brazil, in the years to come.

Note added in proof

After the provisional PDF of this review was available, Dr. Michele Trotta (Laboratorio d’Analisi Veterinarie “San Marco,” Padova, Italy) asked me whether there are cases of canine bartonellosis in Brazil. Cases of Bartonella spp. infection in dogs have been reported worldwide. It was, however, only recently that antibodies to and DNA of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii were detected in dogs from Southeast Brazil [132,239]. Further studies are needed to assess the clinical and zoonotic significance of Bartonella spp. infection in dogs from different Brazilian regions.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Domenico Otranto and Luciana A. Figueredo for their critical reading of the manuscript and to Andrey J. de Andrade for kindly provide the Fig. 4. Thanks also to the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for a PhD scholarship.

References

- Irwin PJ. Companion animal parasitology: a clinical perspective. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:581–593. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter PR. Climate change and waterborne and vector-borne disease. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;94:37S–46S. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.94.s1.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Araújo A. Filaria immitis e a Filaria sanguinolenta no Brasil. Gaz Méd Bahia. 1878;7:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo-Neves VL, Katz G, Rodas LA, Poletto DW, Lage LC, Spínola RM, Cruz OG. Utilização de ferramentas de análise espacial na vigilância epidemiológica de leishmaniose visceral americana – Araçatuba, São Paulo, Brasil, 1998–1999. Cad Saúde Pública. 2001;17:1263–1267. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2001000500026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savani ESMM, Schimonsky B, Camargo MCGO, D'auria SRN. Vigilância de leishmaniose visceral americana em cães de área não endêmica, São Paulo. Rev Saúde Publica. 2003;37:260–262. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102003000200016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa AP, Dossi AC, Oliveira Vasconcelos R, Munari DP, Lima VM. Evaluation of transformation growth factor beta1, interleukin-10, and interferon-gamma in male symptomatic and asymptomatic dogs naturally infected by Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi. Vet Parasitol. 2007;143:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes AH, Ferreira IM, Lima ML, Cunha EA, Garcia AS, Araújo MF, Pereira-Chioccola VL. PCR identification of Leishmania in diagnosis and control of canine leishmaniasis. Vet Parasitol. 2007;144:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira MA, Luvizotto MC, Garcia JF, Corbett CE, Laurenti MD. Comparison of parasitological, immunological and molecular methods for the diagnosis of leishmaniasis in dogs with different clinical signs. Vet Parasitol. 2007;145:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosypal AC, Cortés-Vecino JA, Gennari SM, Dubey JP, Tidwell RR, Lindsay DS. Serological survey of Leishmania infantum and Trypanosoma cruzi in dogs from urban areas of Brazil and Colombia. Vet Parasitol. 2007;149:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolezano JE, Uliana SR, Taniguchi HH, Araújo MF, Barbosa JA, Barbosa JE, Floeter-Winter LM, Shaw JJ. The first records of Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis indogs (Canis familiaris) diagnosed clinically as having canine visceral leishmaniasis from Araçatuba County, São Paulo State, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2007;149:280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes CM, Lima VM, Paula HB, Perri SH, Andrade AM, Dias FE, Burattini MN. Dog culling and replacement in an area endemic for visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2008;153:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regendanz P, Muniz J. O Rhipicephalus sanguineus como transmissor da piroplasmose canina no Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1936;31:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Passos LM, Geiger SM, Ribeiro MF, Pfister K, Zahler-Rinder M. First molecular detection of Babesia vogeli in dogs from Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2005;127:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp SM, Messick JB, Vidotto O, Jojima FS, Morais HS. Babesia gibsoni genotype Asia in dogs from Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2006;141:177–180. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F. Causative agents of canine babesiosis in Brazil. Prev Vet Med. 2008;83:210–211. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro MFB, Lima JD, Passos LMF, Guimarães AM. Freqüência de anticorpos fluorescentes anti-Babesia canis em cães de Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 1990;42:511–517. [Google Scholar]

- Braccini GL, Chaplin EL, Stobbe NS, Araujo FAP, Santos NR. Protozoology and rickettsial findings of the laboratory of the Veterinary Faculty of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 1986–1990. Arq Fac Vet UFRGS. 1992;20:134–149. [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Porto A, Oliveira MR, Miguel O. Babesia canis in stray dogs from the city of São Paulo. Comparative studies between the clinical and hematological aspects and the indirect fluorescence antibody test. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 1993;2:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F, Faustino MAG, Alves LC. Coinfection by Anaplasma platys, Babesia canis and Ehrlichia canis in a dog from Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil: case report. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2004;13:371. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães JC, Albernaz AP, Machado JA, Junior OAM, Garcia LNN. Aspectos clínico-laboratoriais da babesiose canina na cidade de Campos do Goytacazes, RJ. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2004;13:229. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos CV, Moreira SM, Passos LM. Retrospective study (1998–2001) on canine babesiosis in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1026:158–160. doi: 10.1196/annals.1307.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F, Figueredo LA. Canine babesiosis: A Brazilian perspective. Vet Parasitol. 2006;141:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares AO, Souza AD, Feliciano EA, Rodrigues AF, D'Agosto M, Daemon E. Avaliação ectoparasitológica e hemoparasitológica em cães criados em apartamentos e casas com quintal na cidade de Juiz de Fora, MG. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2006;15:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp SM, Dagnone AS, Vidotto O, Freire RL, Amude AM, Morais HS. Seroepidemiology of canine babesiosis and ehrlichiosis in a hospital population. Vet Parasitol. 2006;140:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães AM, Oliveira TMFS, Santa-Rosa ICA. Babesiose canina: uma visão dos clínicos veterinários de Minas Gerais. Clin Vet. 2002;41:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão LP, Hagiwara MK. Babesiose canina: revisão. Clín Vet. 2002;7:50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha AM. Experimental infections in American visceral leishmaniasis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1938;33:581–616. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F. Final comments on an interesting taxonomic dilemma: Leishmania infantum versus Leishmania infantum chagasi. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:929–930. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000800018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira MF, Schubach A, Schubach TM, Pacheco RS, Oliveira FS, Pereira SA, Figueiredo FB, Baptista C, Marzochi MC. Mixed infection with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis and Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi in a naturally infected dog from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:442–445. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho MT, Bueno LL, Sterzik A, Fujiwara RT, Botelho JR, Maria M, Genaro O, Linardi PM. Participation of Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the epidemiology of canine visceral leishmaniasis. Vet Parasitol. 2005;128:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baneth G, Koutinas AF, Solano-Gallego L, Bourdeau P, Ferrer L. Canine leishmaniosis – new concepts and insights on an expanding zoonosis: part one. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F, Faustino MAG, Lima OC, Acioli RV. Epidemiologic surveillance of canine visceral leishmaniasis in the municipality of Recife, Pernambuco. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:444–445. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822005000500017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel EF, Lainson R. Ecologia das leishmanioses: transmissores de leishmaniose tegumentar americana. In: Rangel EF, Lainson R, editor. Flebotomíneos do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2003. pp. 291–310. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas E, Cunha AM, Ferreira LC, Deane L, Deane G, Guimarães FN, Von Paumgartten MJ, Sá B. Leishmaniose visceral americana (Relatório dos trabalhos realizados pela Comissão encarregada do estudo da Leishmaniose visceral americana, em 1937) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1938;33:89–283. [Google Scholar]

- Alencar JE, Cunha RV. Survey of canine kala-azar in Ceara. Latest results. Rev Bras Malariol Doencas Trop. 1963;15:391–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock IA, Almeida SP. Findings on kala-azar in Jacobina, Bahia. II. Canine leishmaniasis. Rev Bras Malariol Doencas Trop. 1969;21:535–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinola Guedes G, Maroja A, Chaves E, Estélio J, Cunha MJ, Arcoverde S. Kala-azar in the coast of Region of the State of Paraiba, Brazil. Findings of 70 human and 16 canine cases. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1974;16:265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho SG, Nunes MP, Marzochi MC, Tramontano N. A survey for American cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis among 1,342 dogs from areas in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) where the human diseases occur. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1985;80:17–22. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761985000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senra MS, Pimentel PS, Souza PE. Visceral leishmaniasis in Santarem/PA: general aspects of the control, serological survey in dogs and treatment of the human cases. Rev Bras Malariol Doencas Trop. 1985;37:47–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos IA, Vasconcelos AW, Momen H, Grimaldi G, Jr, Alencar JE. Epidemiological studies on American leishmaniasis in Ceará State, Brazil. Molecular characterization of the Leishmania isolates. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1988;82:547–554. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1988.11812290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellón EG, Domingos ED. On the focus of kala-azar in the state of Roraima, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1991;86:375. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761991000300014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vexenat JA, Fonseca de Castro JA, Cavalcante R, Silva MR, Batista WH, Campos JH, Pereira FC, Tavares JP, Miles MA. Preliminary observations on the diagnosis and transmissibility of canine visceral leishmaniasis in Teresina, NE Brazil. Arch Inst Pasteur Tunis. 1993;70:467–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borja-Cabrera GP, Correia-Pontes NN, Silva VO, Paraguaide-Souza E, Santos WR, Gomes EM, Luz KG, Palatnik M, Palatnik-de-Sousa CB. Long lasting protection against canine kala-azar using the FML-QuilA saponin vaccine in an endemic area of Brazil (Sao Goncalo do Amarante, RN) Vaccine. 2002;20:3277–3284. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes CB, Pirmez C, Silva ES, Laurentino-Silva V, Steindel M, Santos AJ, Smaniotto H, Silva CF, Schuck Neto VF, Donetto A. Levantamento de leishmaniose visceral em cães de Santa Maria e municípios próximos, Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2003;36:499–501. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822003000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida MA, Jesus EE, Sousa-Atta ML, Alves LC, Berne ME, Atta AM. Clinical and serological aspects of visceral leishmaniasis in northeast Brazilian dogs naturally infected with Leishmania chagasi. Vet Parasitol. 2005;127:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F. Presence of Leishmania amastigotes in peritoneal fluid of a dog with leishmaniasis from Alagoas, Northeast Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop São. 2006;48:219–221. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652006000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F, Brito ME, Brandão-Filho SP. Seroepidemiological survey on canine leishmaniasis among dogs from an urban area of Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2006;140:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocai EA, Frozza L, Headley SA, Graça DL. Leishmaniose visceral (calazar). Cinco casos em cães de Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Ciênc Rural. 1998;28:501–505. [Google Scholar]

- Krauspenhar C, Beck C, Sperotto V, Silva AA, Bastos R, Rodrigues L. Leishmaniose visceral em um canino de Cruz Alta, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Ciênc Rural. 2007;37:907–910. [Google Scholar]

- Dias M, Mayrink W, Deane LM, Costa CA, Magalhães PA, Melo MN, Batista SM, Araujo FG, Coelho MV, Williams P. Epidemiology of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis Americana. I. Study of reservoirs in an endemic region of the State of Minas Gerais. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1977;19:403–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuba Cuba CA, Miles MA, Vexenat A, Barker DC, McMahon Pratt D, Butcher J, Barreto AC, Marsden PD. A focus of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in Três Braços, Bahia, Brazil: characterization and identification of Leishmania stocks isolated from man and dogs. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79:500–507. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falqueto A, Coura JR, Barros GC, Grimaldi Filho G, Sessa PA, Carias VR, Jesus AC, Alencar JT. Participation of the dog in the cycle of transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the municipality of Viana, State of Espirito Santo, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1986;81:155–163. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761986000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida EL, Correa FM, Marques SA, Stolf HO, Dillon NL, Momen H, Grimaldi G., Jr Human, canine and equine (Equus caballus) leishmaniasis due to Leishmania braziliensis (= L. braziliensis braziliensis) in the south-west region of São Paulo State, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1990;85:133–134. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761990000100026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira MF, Uchoa CM, Leal CA, Macedo Silva RM, Duarte R, Magalhães CM, Barrientos Serra CM. Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis em cães naturalmente infectados. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2003;36:551–555. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822003000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade HM, Reis AB, Santos SL, Volpini AC, Marques MJ, Romanha AJ. Use of PCR-RFLP to identify Leishmania species in naturally-infected dogs. Vet Parasitol. 2006;140:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanzarini PD, Santos DR, Santos AR, Oliveira O, Poiani LP, Lonardoni MV, Teodoro U, Silveira TG. Leishmaniose tegumentar americana canina em municípios do norte do Estado do Paraná, Brasil. Cad Saúde Publica. 2005;21:1957–1961. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2005000600047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonardoni MV, Silveira TG, Alves WA, Maia-Elkhoury AN, Membrive UA, Membrive NA, Rodrigues G, Reis N, Zanzarini PD, Ishikawa E, Teodoro U. Leishmaniose tegumentar americana humana e canina no município de Mariluz, Estado do Paraná, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2006;22:2713–2716. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006001200020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro EA, Thomaz-Soccol V, Augur C, Luz E. Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis: epidemiology of canine cutaneous leishmaniasis in the State of Paraná (Brazil) Exp Parasitol. 2007;117:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversson LB, Camargo ME, Villanova A, Reichmann ML, Andrade EA, Tolezano JE. Inquérito sorológico para pesquisa de leishmaniose visceral em população canina urbana no Município de São Paulo, Brasil (1979–1982) Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1983;25:310–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- França-Silva JC, Costa RT, Siqueira AM, Machado-Coelho GL, Costa CA, Mayrink W, Vieira EP, Costa JS, Genaro O, Nascimento E. Epidemiology of canine visceral leishmaniosis in the endemic area of Montes Claros municipality, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2003;111:161–173. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(02)00351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranhos-Silva M, Freitas LA, Santos WC, Grimaldi G, Jr, Pontes-de-Carvalho LC, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ. A cross-sectional serodiagnostic survey of canine leishmaniasis due to Leishmania chagasi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:39–44. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lira RA, Cavalcanti MP, Nakazawa M, Ferreira AG, Silva ED, Abath FG, Alves LC, Souza WV, Gomes YM. Canine visceral leishmaniosis: a comparative analysis of the EIE-leishmaniose-visceral-canina-Bio-Manguinhos and the IFI-leishmaniose-visceral-canina-Bio-Manguinhos kits. Vet Parasitol. 2006;137:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes YM, Paiva Cavalcanti M, Lira RA, Abath FG, Alves LC. Diagnosis of canine visceral leishmaniasis: biotechnological advances. Vet J. 2008;175:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miró G, Cardoso L, Pennisi MG, Oliva G, Baneth G. Canine leishmaniosis – new concepts and insights on an expanding zoonosis: part two. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzochi MC, Coutinho SG, Souza WJ, Toledo LM, Grimaldi Júnior G, Momen H, Pacheco RS, Sabroza PC, Souza MA, Rangel Júnior FB. Canine visceral leishmaniasis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Clinical, parasitological, therapeutical and epidemiological findings (1977–1983) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1985;80:349–357. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761985000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro VM, Rajao RA, Diniz SA, Michalick MSM. Evaluation of the potential transmission of visceral leishmaniasis in a canine shelter. Revue Méd Vét. 2005;156:20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Schettini DA, Costa Val AP, Souza LF, Demicheli C, Rocha OG, Melo MN, Michalick MS, Frézard F. Pharmacokinetic and parasitological evaluation of the bone marrow of dogs with visceral leishmaniasis submitted to multiple dose treatment with liposome-encapsulated meglumine antimoniate. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2005;38:1879–1883. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005001200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda-Garcia FA, Lopes RS, Marques FJ, Lima VM, Morinishi CK, Bonello FL, Zanette MF, Perri SH, Feitosa MM. Clinical and parasitological evaluation of dogs naturally infected by Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi submitted to treatment with meglumine antimoniate. Vet Parasitol. 2007;143:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miret J, Nascimento E, Sampaio W, França JC, Fujiwara RT, Vale A, Dias ES, Vieira E, Costa RT, Mayrink W, Campos Neto A, Reed S. Evaluation of an immunochemotherapeutic protocol constituted of N-methyl meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime((R))) and the recombinant Leish-110f((R))+MPL-SE((R)) vaccine to treat canine visceral leishmaniasis. Vaccine. 2008;26:1585–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro VM. Leishmaniose visceral canina: aspectos de tratamento e controle. Clín Vet. 2007;71:66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda-Garcia FA, Lopes RS, Ciarlini PC, Marques FJ, Lima VM, Perri SH, Feitosa MM. Evaluation of renal and hepatic functions in dogs naturally infected by visceral leishmaniasis submitted to treatment with meglumine antimoniate. Res Vet Sci. 2007;83:105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massard CA. MSc dissertation. Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Parasitologia; 1979. Hepatozoon canis (James, 1905) (Adeleida: Hepatozoidae) de cães do Brasil, com uma revisão do gênero em membros da ordem carnívora. [Google Scholar]

- Rubini AS, Paduan KS, Cavalcante GG, Ribolla PEM, O'Dwyer LH. Molecular identification and characterization of canine Hepatozoon species from Brazil. Parasitol Res. 2005;97:91–93. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criado-Fornelio A, Ruas JL, Casado N, Farias NA, Soares MP, Muller G, Brumt JG, Berne ME, Buling-Saraña A, Barba-Carretero JC. New molecular data on mammalian Hepatozoon species (Apicomplexa: Adeleorina) from Brazil and Spain. J Parasitol. 2006;92:93–99. doi: 10.1645/GE-464R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano MD, Teixeira KR, Scofield A, Elisei C, Yotoko KS, Fernandes KR, Linhares GF, Ewing SA, Massard CL. Molecular characterization of Hepatozoon sp. from Brazilian dogs and its phylogenetic relationship with other Hepatozoon spp. Vet Parasitol. 2007;145:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dwyer LH, Massard CL, Souza JCP. Hepatozoon canis infection associated with dog ticks of rural areas of Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2001;94:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(00)00378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano M, Scofield A, Elisei C, Fernandes KR, Ewing SA, Massard CL. Diagnosis of Hepatozoon spp. in Amblyomma ovale and its experimental transmission in domestic dogs in Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2005;134:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubini AS, Paduan KD, Lopes VV, O'Dwyer LH. Molecular and parasitological survey of Hepatozoon canis (Apicomplexa: Hepatozoidae) in dogs from rural area of Sao Paulo state, Brazil. Parasitol Res. 2008;102:895–899. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0846-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondim LF, Kohayagawa A, Alencar NX, Biondo AW, Takahira RK, Franco SR. Canine hepatozoonosis in Brazil: description of eight naturally occurring cases. Vet Parasitol. 1998;74:319–323. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(96)01120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paludo GR, Dell'Porto A, Castro e Trindade AR, McManus C, Friedman H. Hepatozoon spp.: report of some cases in dogs in Brasília, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2003;118:243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dwyer LH, Saito ME, Hasegawa MY, Kohayagawa A. Tissue stages of Hepatozoon canis in naturally infected dogs from Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Parasitol Res. 2004;94:240–242. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundim AV, Morais IA, Tavares M, Cury MC, Mundim MJS. Clinical and hematological signs associated with dogs naturally infected by Hepatozoon sp. and with other hematozoa. A retrospective study in Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2008;153:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F, Figueredo LA, Faustino MAG. Ectoparasitos de cães provenientes de alguns municípios da região metropolitana do Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2004;13:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Baneth G, Mathew JS, Shkap V, Macintire DK, Barta JR, Ewing AS. Canine hepatozoonosis: two disease syndromes caused by separate Hepatozoon spp. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(02)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar DM, Ribeiro MG, Silva WB, Dias JG, Jr, Megid J, Paes AC. Hepatozoonose canina: achados clínico-epidemiológicos em três casos. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2004;56:411–413. [Google Scholar]

- O'Dwyer LH, Massard CL. Hepatozoonose em pequenos animais domésticos e como zoonose. In: Almosny NRP, editor. Hemoparasitoses em pequenos animais domésticos e como zoonose. Rio de Janeiro: L.F. Livros de Veterinária; 2002. pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing SA, Panciera RJ. American canine hepatozoonosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:688–697. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.4.688-697.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas CRJ. Nova tripanosomíase humana. Estudos sobre a morphologia e o ciclo evolutivo do Schizotrypanum cruzi n. gen. n. esp., agente da nova entidade mórbida do homem. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1909;1:159–218. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JR, Nunes VL, Lanham SM, Oshiro ET. Isoenzyme characterization of Trypanosoma evansi isolated from capybaras and dogs in Brazil. Acta Trop. 1989;46:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(89)90021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke CR, Greiner M, Mehlitz D. Investigations on naturally occurring Trypanosoma evansi infections in horses, cattle, dogs and capybaras (Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris) in Pantanal de Poconé (Mato Grosso, Brazil) Acta Trop. 1994;58:159–169. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz AO, Cabello PH, Jansen AM. Biological and biochemical characterization of isolates of Trypanosoma evansi from Pantanal of Matogrosso–Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2000;92:107–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(00)00286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera HM, Dávila AM, Norek A, Abreu UG, Souza SS, D'Andrea PS, Jansen AM. Enzootiology of Trypanosoma evansi in Pantanal, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2004;125:263–275. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpo CB, Monteiro SG, Stainki DR, Colpo ETB, Henriques GB. Infecção natural por Trypanosoma evansi em cães. Ciênc Rural. 2005;35:717–719. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera HM, Norek A, Freitas TP, Rademaker V, Fernandes O, Jansen AM. Domestic and wild mammals infection by Trypanosoma evansi in a pristine area of the Brazilian Pantanal region. Parasitol Res. 2005;96:121–126. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savani ESMM, Nunes VL, Galati EA, Castilho TM, Araujo FS, Ilha IM, Camargo MCGO, D'auria SRN, Floeter-Winter LM. Occurrence of co-infection by Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi and Trypanosoma (Trypanozoon) evansi in a dog in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:739–741. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762005000700011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciscato C, Lopes STA, Teixeira MMG, Monteiro SG, Garmatz BC, Paim CB. Cão naturalmente infectado por Trypanosoma evansi em Santa Maria, RS, Brasil. Ciênc Rural. 2007;37:288–291. [Google Scholar]

- Mott KE, Mota EA, Sherlock I, Hoff R, Muniz TM, Oliveira TS, Draper CC. Trypanosoma cruzi infection in dogs and cats and household seroreactivity to T. cruzi in a rural community in northeast Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:1123–1127. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett TV, Hoff R, Mott KE, Guedes F, Sherlock IA. An outbreak of acute Chagas's disease in the São Francisco Valley region of Bahia, Brazil: triatomine vectors and animal reservoirs of Trypanosoma cruzi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979;73:703–709. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maywald PG, Machado MI, Costa-Cruz JM, Gonçalves-Pires M. Leishmaniose tegumentar, visceral e doença de Chagas caninas em municípios do Triângulo Mineiro e Alto Paranaíba, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 1996;12:321–328. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x1996000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera L, D'Andrea PS, Xavier SC, Mangia RH, Fernandes O, Jansen AM. Trypanosoma cruzi infection in wild mammals of the National Park 'Serra da Capivara' and its surroundings (Piaui, Brazil), an area endemic for Chagas disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucheis SB, Silva AV, Araújo Júnior JP, Langoni H, Meira DA, Machado JM. Trypanosomatids in dogs belonging to individuals with chronic Chagas disease living in Botucatu town and surrounding region, São Paulo State, Brazil. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis. 2005;11:492–509. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto Dias JC, Schofield CJ, Machado EM, Fernandes AJ. Ticks, ivermectin, and experimental Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:829–832. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762005000800002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falavigna-Guilherme AL, Santana R, Pavanelli GC, Lorosa ES, Araújo SM. Triatomine infestation and vector-borne transmission of Chagas disease in northwest and central Parana, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2004;20:1191–1200. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2004000500012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane LM. Animal reservoirs of Trypanosoma cruzi in Brazil. Rev Bras Malariol Doenças Trop. 1964;16:27–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alencar JE, Almeida YM, Santos AR, Freitas LM. Epidemiology of Chagas' disease in the state of Ceará, Brazil. Rev Bras Malariol D Trop. 1975;26:5–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado EM, Fernandes AJ, Murta SM, Vitor RW, Camilo DJ, Jr, Pinheiro SW, Lopes ER, Adad SJ, Romanha AJ, Pinto Dias JC. A study of experimental reinfection by Trypanosoma cruzi in dogs. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:958–965. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dávila AM, Herrera HM, Schlebinger T, Souza SS, Traub-Cseko YM. Using PCR for unraveling the cryptic epizootiology of livestock trypanosomosis in the Pantanal, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2003;117:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AS, Zanette RA, Colpo CB, Santurio JM, Monteiro SG. Sinais clínicos em cães naturalmente infectados por Trypanosoma evansi (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) no RS. Clín Vet. 2008;13:66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino LPCT, Machado RZ, Alessi AC, Marques LC, Castro MB, Malheiros EB. Clinical, parasitological and immunological aspects of experimental infection with Trypanosoma evansi in dogs. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:255–260. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000200025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandão LP, Larsson MHMA, Birgel EH, Hagiwara MK, Ventura RM, Teixeira MMA. Infecção natural pelo Trypanosoma evansi em cão – Relato de caso. Clín Vet. 2002;7:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MA, Arias JR, Valente SA, Naiff RD, de Souza AA, Povoa MM, Lima JA, Cedillos RA. Vertebrate hosts and vectors of Trypanosoma rangeli in the Amazon Basin of Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:1251–1259. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez LE, Lages-Silva E, Alvarenga-Franco F, Matos A, Vargas N, Fernandes O, Zingales B. High prevalence of Trypanosoma rangeli and Trypanosoma cruzi in opossums and triatomids in a formerly-endemic area of Chagas disease in Southeast Brazil. Acta Trop. 2002;84:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Ramalho ED, Duarte MA, Palma AR, Abad-Franch F, Carranza JC, Cuba Cuba CA. Enzootic transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi and T. rangeli in the Federal District of Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2004;46:323–330. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652004000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia da Silva F, Rodrigues AC, Campaner M, Takata CS, Brigido MC, Junqueira AC, Coura JR, Takeda GF, Shaw JJ, Teixeira MM. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis of Trypanosoma rangeli and allied species from human, monkeys and other sylvatic mammals of the Brazilian Amazon disclosed a new group and a species-specific marker. Parasitology. 2004;128:283–294. doi: 10.1017/s0031182003004554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisard EC, Steindel M, Guarneri AA, Eger-Mangrich I, Campbell DA, Romanha AJ. Characterization of Trypanosoma rangeli strains isolated in Central and South America: an overview. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:203–209. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carini A. Notícias sobre zoonoses observadas no Brasil. Rev Méd São Paulo. 1908;22:459–462. [Google Scholar]

- Loretti AP, Barros SS. Hemorrhagic disease in dogs infected with an unclassified intraendothelial piroplasm in southern Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2005;134:193–213. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestana BR. O nambyuvú (nota preliminar) Rev Soc Sci São Paulo. 1910;5:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana BR. O nambiuvú. Rev Med São Paulo. 1910;22:423–426. [Google Scholar]

- Carini A, Maciel J. Sobre a molestia dos cães, chamada Nambi-uvú, e o seu parasita (Rangellia vitalli) An Paul Med Cir. 1914;3:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Loretti AP, Barros SS. Parasitismo por Rangelia vitalli em cães ("nambiuvú", "peste de sangue") – uma revisão crítica sobre o assunto. Arq Inst Biol. 2004;71:101–131. [Google Scholar]

- Costa JO, Silva M, Batista Junior JA, Guimarães MP. Ehrlichia canis infection in dogs in Belo Horizonte – Brazil. Arq Esc Vet UFMG. 1973;25:199–200. [Google Scholar]

- Torres HM, Massard CL, Figueiredo MJ, Ferreira T, Almosny NRP. Isolamento e propagação da Ehrlichia canis em células DH82 e obtenção de antígeno para a reação de imunofluorescência indireta. Rev Bras Ciênc Vet. 2002;9:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dagnone AS, Morais HS, Vidotto MC, Jojima FS, Vidotto O. Ehrlichiosis in anemic, thrombocytopenic, or tick-infested dogs from a hospital population in South Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2003;117:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macieira DB, Messick JB, Cerqueira AM, Freire IM, Linhares GF, Almeida NK, Almosny NR. Prevalence of Ehrlichia canis infection in thrombocytopenic dogs from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Vet Clin Pathol. 2005;34:44–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165x.2005.tb00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Pinter A, Gennari SM, Camargo LM, Labruna MB. Prevalence of Ehrlichia canis (Rickettsiales:Anaplasmataceae) in dogs and Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae) ticks from Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2007;44:126–132. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[126:poecra]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labruna MB, McBride JW, Camargo LM, Aguiar DM, Yabsley MJ, Davidson WR, Stromdahl EY, Williamson PC, Stich RW, Long SW, Camargo EP, Walker DH. A preliminary investigation of Ehrlichia species in ticks, humans, dogs, and capybaras from Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2007;143:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos F, Coppede JS, Pereira AL, Oliveira LP, Roberto PG, Benedetti RB, Zucoloto LB, Lucas F, Sobreira L, Marins M. Molecular evaluation of the incidence of Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma platys and Babesia spp. in dogs from Ribeirão Preto, Brazil. Vet J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Machado RZ, Duarte JM, Dagnone AS, Szabó MP. Detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in Brazilian marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) Vet Parasitol. 2006;139:262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvão MA, Lamounier JA, Bonomo E, Tropia MS, Rezende EG, Calic SB, Chamone CB, Machado MC, Otoni ME, Leite RC, Caram C, Mafra CL, Walker DH. Rickettsioses emergentes e reemergentes numa região endêmica do Estado de Minas Gerais, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2002;18:1593–1597. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2002000600013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarthe N, Campos Pereira M, Barbarini O, McKee W, Coimbra CA, Hoskins J. Serologic prevalence of Dirofilaria immitis, Ehrlichia canis, and Borrelia burgdorferi infections in Brazil. Vet Ther. 2003;4:67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva Diniz PP, Schwartz DS, Morais HS, Breitschwerdt EB. Surveillance for zoonotic vector-borne infections using sick dogs from southeastern Brazil. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:689–697. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos RS, Muniz Neta ES, Spagnol FH, Oliveira LL, Brito RL, Albuquerque GR, Almosny NR. Freqüência de anticorpos anti-Erhlichia canis, Borrelia burgdorferi e antígenos de Dirofilaria immitis em cães na microrregião Ilhéus-Itabuna, Bahia, Brasil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2007;16:117–120. doi: 10.1590/s1984-29612007000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa LM, Jr, Rembeck K, Ribeiro MF, Beelitz P, Pfister K, Passos LM. Sero-prevalence and risk indicators for canine ehrlichiosis in three rural areas of Brazil. Vet J. 2007;174:673–676. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira D, Nishimori CT, Costa MT, Machado RZ, Castro MB. Detecção de anticorpos anti-Ehrlichia canis em cães naturalmente infectados, através do "DOT-ELISA". Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2000;9:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Almosny NRP, Massard CL. Erliquiose em pequenos animais domésticos e como zoonose. In: Almosny NRP, editor. Hemoparasitoses em pequenos animais domésticos e como zoonose. Rio de Janeiro: L.F. Livros de Veterinária;; 2002. pp. 13–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo GP, Oliveira LP, Zissou VG, Donini IAN, Roberto PG, Marins M. Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene of Anaplasma platys detected in dogs from Brazil. Braz J Microbiol. 2007;38:478–479. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822009000200006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokuma H, Raoult D, Brouqui P. Detection of Ehrlichia platys DNA in brown dog ticks (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) in Okinawa Island, Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4219–4221. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4219-4221.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoi Y, Satoh H, Inokuma H, Kiyuuna T, Muramatsu Y, Ueno H, Morita C. First detection of Ehrlichia platys in dogs and ticks in Okinawa, Japan. Microbiol Immunol. 2001;45:89–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola P, Cornet JP, Sanogo YO, Miller RS, Thien HV, Gonzalez JP, Raoult D, Telford SR, III, Wongsrichanalai C. Detection of Ehrlichia spp., Anaplasma spp., Rickettsia spp., and other eubacteria in ticks from the Thai-Myanmar border and Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1600–1608. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1600-1608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanogo YO, Davoust B, Inokuma H, Camicas JL, Parola P, Brouqui P. First evidence of Anaplasma platys in Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodida) collected from dogs in Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2003;70:205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CM, Yi YH, Yu DH, Lee MJ, Cho MR, Desai AR, Shringi S, Klein TA, Kim HC, Song JW, Baek LJ, Chong ST, O'guinn ML, Lee JS, Lee IY, Park JH, Foley J, Chae JS. Tick-borne rickettsial pathogens in ticks and small mammals in Korea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5766–5776. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00431-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Almeida SMJ, Abboud LC, Bricio AS, Coutinho V, O'Dwyer LH, Daniel C. Ocorrência de Ehrlichia platys em cães no município do Rio de Janeiro examinados no Instituto Municipal de Medicina Veterinária Jorge Vaitsman. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 1993;2:102. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira SM, Bastos CV, Araújo RB, Santos M, Passos LMF. Retrospective study (1998–2001) on canine ehrlichiosis in Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2003;55:141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira RF, Cerqueira AMF, Pereira AM, Guimarães CM, Sá AG, Abreu FS, Massard CL, Almosny NRP. Anaplasma platys diagnosis in dogs: comparison between morphological and molecular tests. Int J Appl Res Vet Med. 2007;5:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sales KG, Braga FRR, Silva ACF, Muraro LS, Siqueira KB. Estudo retrospectivo (2006) da erlichiose canina no Laboratório do Hospital Veterinário da Universidade de Cuiabá. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae. 2007;35:s555–557. [Google Scholar]

- Breitschwerdt EB, Meuten DJ, Walker DH, Levy M, Kennedy K, King M, Curtis B. Canine Rocky Mountain spotted fever: a kennel epizootic. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:2124–2128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser AM, Birkenheuer AJ, Breitschwerdt EB. Canine Rocky Mountain Spotted fever: a retrospective study of 30 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2001;37:41–48. doi: 10.5326/15473317-37-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]