Abstract

Background

Patients who leave hospitals against medical advice (AMA) may be at risk for adverse health outcomes. Their decision to leave may not be clearly understood by providers. This study explored providers’ experiences with and attitudes toward patients who leave the hospital AMA.

Objective

To explore providers’ experiences with and attitudes toward patients who leave the hospital AMA.

Methods

We conducted interviews with university-based internal medicine residents and practicing internal medicine clinicians caring for patients at a community hospital from July 2006 to August 2007. We approached 34 providers within 3 days of discharging a patient AMA. The semi-structured instrument elicited perceptions of care, emotions, and challenges faced when caring for patients who leave AMA. Using an editing analysis style, investigators independently coded transcripts, agreeing on the coding template and its application.

Participants

All 34 providers (100%) participated. Providers averaged 32.6 years of age, 22 (61%) were men, 20 (59%) were housestaff from three residency programs, 13 (38%) were faculty, hospitalist physicians, or chief residents serving as ward attendings, and one (3%) was a physician assistant.

Main Results

Four themes emerged: 1) providers’ beliefs that patients lack insight into their medical conditions; 2) suboptimal communication, mistrust, and conflict; 3) providers’ attempts to empathize with patients’ concerns; and 4) providers’ professional roles and obligations toward patients who leave AMA.

Conclusion

Our study revealed that patients who leave AMA influence providers’ perceptions of their patients’ insight, and their own patient–provider communication, empathy for patients, and professional roles and obligations. Future research should investigate educational interventions to optimize patient-centered communication and support providers in their decisional conflicts when these challenging patient–provider discussions occur.

KEY WORDS: hospitalization, patient discharge, patient–provider communication, difficult patient, professionalism

INTRODUCTION

Patients go to hospitals to receive care for illnesses they cannot manage at home. Appropriate inpatient care requires that providers understand and treat each patient’s presenting complaints and address comorbidities, health behaviors, and psychosocial risk factors that may contribute to poor outcomes. In their report Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institute of Medicine described optimal inpatient care as patient-centered: “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”1

One in every 70 hospital discharges occurs against medical advice (AMA).2 Patients who leave AMA may be at risk for adverse health outcomes leading to more frequent hospital readmissions and increased morbidity and mortality.3–6 Prior retrospective chart review studies have found that the likelihood of AMA discharges is associated with hospital factors such as size and location2 and patient factors such as mental illness,4,7 substance abuse,4,5,7–9 gender,2,5,7–9 income,2,5 lack of medical insurance,8,9 whether the individual is a Medicaid recipient,2,9 race,2,8–10 and young age2,5,7,9,11. One chart review found that providers document patients’ reasons for leaving AMA as personal issues, financial problems, and legal matters.12

A patient’s choice to leave AMA may represent a breakdown in communication, which in turn relates to a variety of patient, provider, and relationship factors.13–15 In addition, this decision may create conflict for providers in balancing their ethical obligations: respecting patient autonomy and self-determination, and protecting the patient from harm.16 While some information is known about patient factors associated with leaving AMA, no studies have assessed providers’ perspectives on their interactions with these patients. Since providers may have insight into the events leading to premature departure, our research focused on providers’: 1) actions when they found out a patient wished to leave prematurely; 2) feelings regarding the experience; and 3) lessons learned.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

We conducted one-on-one interviews to investigate providers’ experiences with and perspectives regarding patients who leave the hospital AMA. We chose a qualitative methodology, which allows greater in-depth exploration and emergence of themes unanticipated by the investigators than is possible using closed-ended questionnaires.17 We also attempted to telephone patients within 7 days of an AMA discharge to learn their reasons for leaving and perspectives on care. Although multiple attempts were made, we reached only four patients, which we deemed an insufficient number to analyze.

We targeted all internal medicine providers (physicians-in-training, attending physicians, or physician assistants) providing inpatient care for a patient who left AMA from an urban hospital in Connecticut. This 405-bed hospital located in Waterbury, Connecticut, hosts inpatient rotations for three internal medicine residencies from the Yale University School of Medicine, has a 13-provider hospitalist service and a cadre of community physicians who admit patients with and without resident coverage. Waterbury has a population of 107,000 and a per capita average income $4,000 less than the national average.18 See Table 1 for other regional and national demographic comparisons.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Who Chose to Leave Against Medical Advice from a Connecticut Hospital Compared with Regional and National Characteristics*

| Study patient demographics | Regional demographics | US demographics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 44.8 | 36.7 | 36.2 |

| Male, (%) | 68.8 | 47.3 | 49.1 |

| Race, (%) | |||

| White | 68.8 | 67.1 | 75.1 |

| African American | 12.5 | 16.3 | 12.3 |

| Hispanic | 18.7 | 21.8 | 12.5 |

| Asian | 0 | 1.5 | 3.6 |

| High school or greater education, % | — | 71.7 | 80.4 |

| Marital status (married), % | 25.0† | 45.0 | 54.4 |

| Employment rate, % | 25.0‡ | 61.2 | 63.9 |

| Median per capita income, $ | — | 17,701 | 21,587 |

| Uninsured, % | 37.0 | 10.4§ | 15.3%|| |

*Regional and national demographics were obtained from the 2000 Census Report except were indicated (Census 2000 demographic profiles. Available athttp://www.ctnow.com/extras/census/0600900980070.pdf.) Regional demographics are specific to Waterbury, Connecticut except for the uninsured rate

†Marital status was unknown for 13% of patients

‡Employment status was not available for 19% of patients

§Represents Connecticut’s overall uninsured rate obtained from U.S. Census Bureau. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2006. http://www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/p60-233.pdf

||National uninsured rate obtained from U.S. Census Bureau. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2006. http://www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/p60-233.pdf

From July 2006 to August 2007, we examined daily hospital discharge logs for patients who left AMA. We contacted each AMA patient’s medical providers within three days of discharge in order to obtain the most accurate account of experiences and emotions. One provider had two AMA patients but only the interview about the first patient was included in our analysis. Sampling was discontinued when thematic saturation was achieved.17

We obtained written consent from each participant. The Waterbury Hospital Institutional Review Board and the Yale University Human Investigation Committee approved the study protocol.

Data Collection

One investigator (DMW) conducted audiotaped, semi-structured interviews with consenting respondents in a private setting inside the hospital. Each interview began with the participant describing the medical circumstances surrounding the patient’s admission to the hospital. The interview instrument was in part derived from the Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire,19 a survey instrument with high construct validity and internal consistency designed to examine patients’ hospital experiences. We included the 10 items deemed most pertinent to communication with patients who choose to leave AMA (Appendix). The interviewer used reflective probes to encourage respondents to clarify and expand on their statements. We obtained patient demographic characteristics by chart review.

Data Analysis

We analyzed transcripts using an “editing analysis style,” wherein the analysts seek meaningful segments of data to create codes, deriving the coding template from the data itself.17 The two study investigators independently analyzed six randomly selected transcripts to generate a list of codes summarizing the subjects’ statements. Each code could occur more than once in a transcript, and each quotation could be associated with more than one code. Investigators compared codes and negotiated discrepancies to create a consensus coding template, discussing and agreeing on the application of final coding categories. We independently applied this template to all remaining transcripts. Coder agreement was high (κ = 0.97). Themes presented were chosen by consensus based on the most frequent codes. We reviewed all available quotations for associated themes and chose representative quotations with the aim of presenting viewpoints from all provider types. To help establish validity of our themes, a random sample of 50% of provider respondents reviewed our data and agreed with our summary.

We managed and analyzed data using Atlas.ti 5.0 software (Atlas.ti GmbH, Berlin, Germany, 2005), a qualitative analysis software developed from a type of editing analysis style called the grounded theory approach.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Patients who left AMA were more likely to be older, male, unemployed, and uninsured compared to regional and national demographics (Table 1). Many patients smoked (75%), and some were involved with illicit drugs (38%).

Respondent Characteristics

All 34 clinicians agreed to be interviewed (100% response rate). Providers included resident trainees, attending physicians, and one physician assistant. More trainees had patients who left AMA compared to private or hospitalist physicians. Provider characteristics are described in Table 2. Interviews lasted 8 to 25 minutes.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 34 Physicians Interviewed Regarding Patients Who Choose to Leave Against Medical Advice from a Connecticut Hospital

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 32.6 (6.2) |

| Men, (%) | 22 (61.1) |

| Provider description, (%) | |

| Preliminary intern, primary care program | 2 (5.9) |

| Intern, primary care program | 8 (23.5) |

| Resident, primary care program | 7 (20.6) |

| Resident, medicine/pediatrics program | 2 (5.9) |

| Resident, traditional internal medicine program | 1 (2.9) |

| Chief resident serving as ward attending | 3 (8.8) |

| Hospitalist | 6 (17.7) |

| Subspecialist | 2 (5.9) |

| General internist | 2 (5.9) |

| Physician assistant | 1 (2.9) |

Providers’ Quantitative Characterizations of AMA Interactions

Providers reported spending an average of 44 minutes with patients discussing their decisions to leave AMA. A majority of providers stated that their patients explicitly told them why they were leaving AMA. However, most providers speculated that patients’ reasons may have been multi-factorial and only partially disclosed to them. Actions taken by providers at the time the patient wished to leave AMA and their assessment of the patient are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Actions Taken or Assessment of Patients by 34 Providers whose Patients Left the Hospital Against Medical Advice

| Providers’ Action/Assessment | # of providers |

|---|---|

| Patient asked questions about their condition or treatment | Many |

| Patient had anxieties/fears about condition or treatment | A few |

| Action taken after hearing patient wanted to leave | |

| Went to patient bedside to discuss desire to leave | Many |

| Contacted another provider (colleague or supervising physician) | A few |

| Found out after the fact | A few |

| Did nothing | A few |

| Contacted risk management | A few |

| Contacted security | A few |

| Contacted psychiatry | A few |

| Patient was asked to sign a form stating they were leaving AMA | A majority |

| Follow-up plans were made to ensure patient’s safety | A majority |

| Illness of patient at time of leaving | |

| Poor | A few |

| Fair | Many |

| Good | A few |

| Very good | A few |

| Excellent | None |

| Treated patient with dignity and respect | |

| Sometimes | A few |

| Always | A majority |

| Would change something that happened with the patient if could | Many |

| Would change something in care of other patients given this experience | Many |

Results of Qualitative Analysis

Four themes emerged from the interviews: 1) providers’ beliefs that patients lack insight into their medical conditions; 2) suboptimal communication, mistrust, and conflict; 3) providers’ attempts to empathize with patients’ concerns; and 4) providers’ professional roles and obligations towards patients who leave AMA. Table 4 shows code counts for these themes.

Table 4.

Code Count from an Interview Study of 34 Providers Caring for Patients who Left Against Medical Advice from a Connecticut Hospital

| Category | # of codes | # of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Patients’ lack of insight about their medical conditions | ||

| Providing medical information | 58 | A majority |

| Limited or no insight about medical conditions | 55 | A majority |

| Feeling fine | 41 | Many |

| Suboptimal communication, mistrust, and conflict | ||

| Withholding information: I just want to go home | 47 | A majority |

| Suspicion about true movies/substance abuse | 47 | Many |

| Conflict | 55 | Many |

| Providers’ attempts to empathize with patients’ concerns | ||

| Competing responsibilities | 28 | A few |

| Fear | 24 | Many |

| Upset about care | 61 | A majority |

| Communicating empathy and respect to patients | ||

| Spending time with patient | 48 | A majority |

| Showing respect and caring | 35 | All |

| Eliciting patient concerns | 28 | Many |

| Negotiating to meet other concerns | 55 | A majority |

| Providers’ professional roles and obligations towards patients who leave AMA | ||

| Self-doubt | 58 | A majority |

| Missed opportunities | 42 | A majority |

| Did all I could do | 42 | A majority |

| Autonomy | 21 | Many |

| Futility | 13 | A few |

Theme 1: Providers’ beliefs that patients lack insight into their medical conditions Regardless of patients’ stated motivations, providers felt that patients’ decisions to leave AMA demonstrated lack of comprehension about the dangers of their current medical conditions. This left providers attempting to provide their patients with medical information in hopes of convincing them to stay.

Lack of Insight Concern about patients’ lack of insight — expressed by a majority of providers — was explained by one attending physician this way:

He did not seem to make the connection that dealing with his active inpatient issues was an important part of his recovery from his illness.

One resident felt that his patient did not comprehend what hospitalization and hospital care meant:

I don’t think that the patient ever really wanted to be in the hospital. It is almost like he thought that the hospital was like fast food. You are hungry and you go and get a meal really quickly, and then you get out. That is pretty much it.

Feeling Fine Many providers attributed lack of insight to patients “feeling fine,” either having recovered from their symptoms or having an underlying asymptomatic condition. A resident stated:

I do not think that he had any real understanding of how sick he was. I think that, in his mind, what he was saying was true. He felt better. He was eating. His strength was improved, and there was no reason for him to stay there.

Providing Medical Information Providing medical information to patients was a common strategy for trying to convince patients to stay in the hospital. Providers gave patients detailed medical information regarding the dangers of leaving, including health risks of deferring treatment, need for further diagnostic testing, and potential for serious illness or death.

One intern detailed:

I talked about the risks of him going home. Not being monitored by medical personnel. We talked about the risk of him being home with two young children and no adults. The risk of him going into a seizure and not having anyone to help him, especially when his medications are not therapeutic.

Theme 2: Suboptimal Communication, Mistrust, and Conflict Overall, providers felt that the quality of provider–patient communication was suboptimal, either due to resistance on the patient’s part or miscommunication by providers.

Withholding Information: “I Just Want to Go Home.” One type of suboptimal communication was demonstrated by providers’ perceptions that patients did not truly articulate a reason for leaving AMA. Providers most often said that patients simply stated they did not want to be in the hospital or wanted to go home. As noted by an attending:

All she said was that she wanted to go home and sleep in her own bed.

Similarly, a resident discussed the reasons for his patient’s decision:

He mentioned that he was just tired of being in the hospital. He did not give any particular irritating or inciting problems for those feelings. He said just very nonspecifically a phrase like, “I have things to do.” There was no particular thing that seemed to be bothering him.

Suspicion about True Motives The lack of explicit rationale led some providers to speculate that “wanting to go home” masked patients’ true reasons for leaving AMA, including intentions to engage in less desirable activities. Many providers cited alcohol or other substance abuse as potential motivators, as a resident described:

My thought is that he may not have been interested in doing the rehabilitation, as well as his need to do more substance abuse, which he cannot do in a hospital. When the social worker talked to him, he had no interest in quitting his cocaine or heroin....

This intern explained how suspicion of substance abuse surfaces in her conversations with certain patients who choose to leave AMA:

I think that is a question that we as housestaff ask ourselves every time: ‘Why did this patient want to leave?’ Was he withdrawing from alcohol? He knows that if he goes outside that he will either drink again or can potentially get into serious problems with withdrawal.

Conflict Providers also noted past conflicts with patients. One attending felt that he could never see eye to eye with his patient regarding medical diagnoses:

[The patient] actively disagreed when you suggested that anything else might be wrong.

Another attending relayed a similar story of conflict:

People were telling him that he had colitis, but he said, ‘Well, no, I do not have any diarrhea. They are diagnosing me wrong’.... [I replied,] ‘We are not saying that you have diarrhea, it is just that is what it is termed and so we need to investigate that.’

Another attending described conflict over concerns for patient deception:

I felt just frustrated and taken advantage of. From the beginning when I heard her story it just seemed like this was a woman who was drug-seeking and then, after I met her and examined her, she seemed so fine. I really felt like she was trying to manipulate the system, and I resented it.

Theme 3: Providers’ Attempts to Empathize with Patients’ Concerns Some providers expressed empathy for their patients’ feelings and decisions.

Competing Responsibilities Providers acknowledged that some patients may have competing concerns that they prioritized over their health.

An intern described his patient’s family obligations and commitments:

He stayed with his sister with two young children.... He felt that it was his responsibility to go back home and take care of those kids so that his sister could go back to work.

An attending cited her patient’s responsibilities as a parent and caregiver as motivating factors to leave:

She said that she has some personal issues to take care of, and there was an issue with one of her children and court, and then her grandchildren that she takes care of, and she really needed to get home.

Fear Other providers felt that patients chose to leave because of emotional distress with their medical conditions.

An attending felt that the patient’s fear about his illness was truly behind his desire to leave:

He definitely had some fears that he discussed even on the last day. He had multiple friends who had died from HIV-related complications.

Upset About Care Some providers expressed understanding of why patients might have felt anger or frustration with the care they received in the hospital.

An intern explained how the patient felt uninvolved in his care:

I think that he got frustrated with sitting in a hospital bed and not much was changing, and waiting for something to happen, and not knowing what decisions, advice, or suggestions were being debated among his caregivers.

Communicating Empathy and Respect to Patients The capacity to understand patients’ competing concerns and emotional reactions to their health allowed some providers to try different approaches to discussing patients’ decisions to leave AMA.

The most common communication approach by providers was to spend time with the patient. One intern reflected on the importance of time:

Foremost, I spent a great deal of time with the person. I spent an hour with the patient. I took the time to inquire why the patient wanted to leave the hospital.

Showing caring for patients was also a common communication strategy, as noted by this intern:

If you put in enough effort and communicate in an open, caring fashion, they tend to listen and respect your opinion.

Providers also described the importance of eliciting patients’ concerns. In the words of one attending:

Most of the time, it requires sitting down with someone and identifying their concerns.

This intern recounted a similar strategy with his patient:

Mainly, I started with an opening question to see what was on his mind.... What is the reasoning around his wanting to leave?

Providers also discussed negotiating with patients to meet other concerns and needs in a way that would allow them to stay in the hospital:

I try to sit down and talk to them and try to understand what their frustrations are. I try to get to the core of why they want to leave AMA. I offer them support and try to get social work involved. If necessary, I try to do some give and take. Sometimes the patients may want something as simple as a pass to just leave the floor to see the light of day. Sometimes you can get someone to assist them to go down. Just simple things like that.

Theme 4: Providers’ Professional Roles and Obligations toward Patients Who Leave AMA Providers reflected how their experiences with patients leaving AMA made them reconsider their professional roles and obligations toward challenging patient relationships.

Self-Doubt and Uncertainty about Missed Opportunities Providers most often discussed self-doubt about their inability to secure patients’ diagnoses by the time they left the hospital. One resident noted:

Because he had something going on but we just could not figure out what it was....

Providers also discussed uncertainty regarding other resources that could have been offered to the patient. One attending recounted:

I don’t know what else, what other resources we have to talk to the patient about. It is too complicated, patient care is, and the time we spend.... I am not an expert in social services, but maybe they can spend some time.

Many providers experienced a missed opportunity to interact with their patients prior to their leaving, as explained by one attending:

I just wish that we were able to know that he was leaving. I wish that somehow we could have identified that he was leaving the hospital and tried to intervene.

Missed opportunities often occurred because providers were busy with other patients or activities, and thus unavailable to the patient. One resident reflected:

I did not feel very good about the way that he left. I think that it was mainly because we were not there and there was a lot going on that day.

The Dilemma of Respecting Patient Autonomy In achieving empathy for patients’ non-medical concerns, providers still struggled with their patients’ right to prioritize those concerns over their health. An intern described this dilemma as follows:

Especially in these situations, it is hard to understand a patient’s rationales because, from a care providers’ perspective, health is the most important thing, because that is what we try to address. A lot of time, patients have other circumstances in life that are more important to them than health.

The importance of allowing patients’ their autonomy was acknowledged by one attending who asserted:

I think that it was a difficult situation, a troubling situation because I acknowledge and believe the importance of giving people determination over their own decision making.

Another attending felt that yielding control and autonomy in making decisions would help convince patients to stay:

Sometimes I feel that if you say to the patient, ‘You know you are a grown up and you are free to leave, but these are the reasons why I think that you should stay and this is what is going to happen to you if you leave’ then they often calm down and make the decision to stay.

Maintaining Responsibility versus Accepting Futility Many providers maintained their sense of responsibility to patients who wished to leave AMA, with a majority participants citing ways they would improve future interactions. One intern discussed improving her communication with patients by providing more information regarding their condition and treatment:

I would make more of an effort to help patients understand their condition, the implications of their condition, and the prognosis, and then allow them to make a decision on whether or not to leave the hospital.

An attending took responsibility for eliciting the patient’s concerns:

I would identify the reason that they are in the hospital from their perspectives and try to talk about it at length so the patients do not get disillusioned.

At the same time, an overlapping group of participants expressed the view that they did all they could do to help their patients. A few providers felt that trying to change approaches would be futile. One intern reflected:

I feel like I covered all of the bases with my approach to him, and unfortunately, regardless of our efforts, we can not make a patient do what we want them to do all of the time.

The sense of futility was shared by another intern who said:

Despite all of our efforts, there is no way to ensure 100% of the people are going to stay in the hospital. I think that the lesson to this is that, no matter what we do sometimes you can’t keep everyone in-house. It is unfortunate.

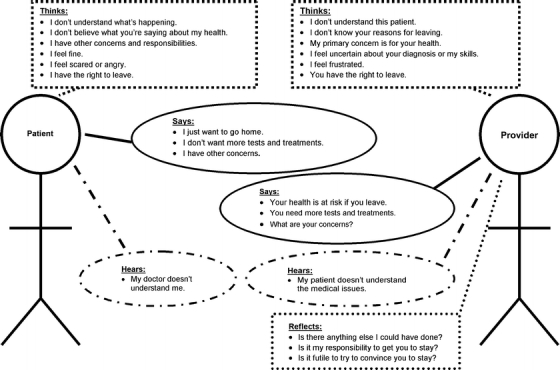

Conceptual Diagram of Patient–Provider Communication about Decisions to Leave AMA

Based on the codes and themes from our study, we have created a pictorial representation from the provider perspective of what providers and patients think, say, and hear when communicating about decisions to leave AMA. (See Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Conceptual depiction of providers’ perceptions of what is thought, said, and heard when a patient chooses to leave the hospital against medical advice from an interview study of 34 providers in a Connecticut Hospital.

DISCUSSION

Patients who leave the hospital prior to a desired endpoint present a challenge to many providers. These challenges often evoke strong feelings, including concern for a patient’s health and safety, frustration, and ineptitude.

Four themes emerged from our study. The first involved the providers’ assessment that patients lack insight into their medical condition. To address this issue, providers often spent time discussing the patient’s medical condition and treatment options. Despite attempts at patient education, providers’ and patients’ views toward health, disease, and illness may differ fundamentally. Arthur Kleinman distinguishes between the illness — the patient’s “lived experience” — and the disease — the provider’s biomedical explanation for what is occurring.20 A patient’s meaning of illness may be shaped by their symptoms, how those symptoms translate into knowledge about themselves and the culture of their wider psychosocial environment.20 Thus, the common reaction to leaving AMA — offering medical information to raise the patient’s awareness about their disease — may be insufficient by itself.

In our second theme, we found that suboptimal communication, mistrust, and conflict emerged as potential reasons patients left AMA. A study evaluating views of hospitalization by patients and providers found little agreement between the two groups with respect to justification of hospital stay and discharge planning.21 This discrepancy was felt to be due in part to poor patient-physician communication.21 Another study to determine what patients’ value most during hospitalization established that confidence and trust in providers, treatment with respect and dignity, and adequacy of involvement in care were the most important factors.22 These studies support the importance of effective communication and relationship building skills. Governing and accreditation bodies23–25 and the Institute of Medicine1 also recognize these skills as paramount; they have also been linked to important outcomes including improved diagnostic and clinical proficiency,26,27 reduced patient emotional distress,26 and increased patient and provider satisfaction.28–30

Many providers attempted to empathize with their patients in the third theme that emerged. In doing so, they made an effort to elicit concerns and communicate in an open, caring fashion. Some providers recognized a power struggle between themselves and their patients regarding individual needs. These providers identified the importance of negotiation and working together to find common ground as keys to persuading patients to stay in the hospital. Educators recommend that providers in challenging interactions take an approach characterized by collaboration through improved partnership, and appropriate use of power, negotiation, and empathy.31,32 Opening the lines of communication earlier and often during patient interactions may have prevented many of the misconceptions providers described in our study from occurring (Fig. 1).

Our fourth theme addressed professional roles and obligations toward patients who leave AMA. The code of medical ethics,33 which emphasizes respecting the rights of patients and their right to self-determination, appears to conflict with what providers learn regarding the legality of patients who leave AMA. Literature about AMA patients often focuses on the provider’s duty to determine patient capacity and qualifications for involuntary commitment.34,35 Scholarship in this domain discusses risk management strategies, noting that improving patient-physician communication can lead to decreased patient complaints and fewer malpractice claims.36,37 Articles also articulate the importance of careful and thorough documentation of the actions taken by the patient and the provider in the sequence of events that lead up to and include leaving the hospital AMA.34 These legal and procedural themes echo loudly in providers’ thoughts as they try to balance patient autonomy, potential harm, and beneficence. This leaves some providers conflicted about their roles and obligations.

What strategies could help providers struggling with the four themes described above? Interpersonal conflicts may be remedied if providers embrace different responsibilities in their care. Carrese discusses the exploration of treatment refusal in order to better understand the patient’s beliefs, expectations, fears, and personal needs.16 He recommends exploring “religious beliefs, cultural background, various psychosocial factors, previous interactions with the health care system, influential personal experiences, or the preferences of family members or friends.”16 Beginning in the first interview, this process may reveal that patients don’t actually lack insight, but are informed about their health in different ways. If, despite this effort, a patient still desires to leave before treatment is deemed completed, Swota recommends maximizing patient autonomy through mandatory post-hospital follow-up contact.38 These two methods use a patient-centered approach to care, and move beyond conflict, and allow both parties to effectively carry out their individual roles and obligations.

Providers struggling to come to terms with how these experiences shape their professional identity may benefit from reflecting on their own assumptions, feelings, and attitudes when a patient wants to leave AMA. Based on the themes in this study, we offer eight questions that providers may ask themselves — rather than their patients — to assess their own capacity and insight in these situations (Table 5).

Table 5.

Assessing Your Own Capacity: Eight Questions Providers Should Ask Themselves When a Patient Wants to Leave Against Medical Advice

| Theme encountered when a patient wishes to leave AMA | Questions for self-reflection |

|---|---|

| Belief that the patient lacks insight into their medical conditions | 1. Do I have full insight into this patient’s beliefs about health and illness? |

| 2. How can I use my insight to counsel this patient in a patient-centered way? | |

| Suboptimal communication, mistrust, or conflict | 3. What factors are making it difficult for us to communicate? |

| What is it about: | |

| •This patient? | |

| •The system? | |

| •Me? | |

| 4. How can I re-establish my trust in this patient and this patient’s trust in me? | |

| Empathizing with the patient’s concerns | 5. What are this patient’s concerns about remaining in the hospital? |

| 6. How can I acknowledge those concerns and communicate empathy and respect for this patient? | |

| Professional roles and obligations towards the patient who wishes to leave AMA | 7. How does this patient’s desire to leave make me feel about myself? |

| 8. How does this patient’s desire to leave make me feel about my professional responsibilities toward this patient? |

Our study has several limitations. First, as a qualitative study limited to clinicians at a single institution, our findings may not apply to health care providers in other hospitals or settings. At the same time, our study design was strengthened by our high response rate and our inclusion of providers from a variety of levels. Second, our study did not include the perspectives of the patients who left AMA, their significant others, or their other care providers in the hospital. Although soliciting patients’ perspectives was an additional aim of this study, the investigators were unable to recruit sufficient numbers of participants for theoretical saturation. Given the fact that many of these challenges are interpersonal in nature, it is especially important that future research gather data from all stakeholders in the decision to leave AMA.

In conclusion, our study revealed that patients who leave AMA raise questions for providers about their patients’ level of insight, quality of communication, need for empathy and professional roles and obligations. Future research should investigate educational interventions to optimize patient-centered communication and support providers in their decisional conflicts when these challenging patient–provider discussions occur.

Acknowledgement

None. No financial disclosures.

Conflicts of Interest None disclosed.

APPENDIX

Interview Guide for Semi-Structured Interviews with Providers Regarding Their Experiences with a Patient Who Has Left the Hospital Against Medical Advice

Do you recall taking care of patient X in the hospital recently?

Could you review the circumstances around the patient’s admission to the hospital?

Did your patient ask you questions about their condition or treatment? (Yes, No my patient had no questions)

If your patient did have questions, do you feel that you answered them thoroughly? (Yes always, Yes sometimes, No)

Did you feel that your patient had anxieties or fears about their condition or treatment? (Yes, No my patient did not have anxieties/fears)

If your patient had anxieties or fears, did you discuss them with the patient? (Yes completely, Yes to some extent, No)

Did your patient have friends or family members with questions regarding the patient’s condition or treatment? (Yes, No family or friends were involved, Family/friends did not need/request information)

If friends or family were involved, do you feel that you provided all of the information they needed? (Yes definitely, Yes to some extent, No)

Did your patient ever complain of pain when they were in the hospital? (Yes, No)

-

If they were in pain, do you think did everything you could to help control their pain?

(Yes definitely, Yes to some extent, No)

When you were in the room with the patient, did you talk in front of your patient as if he/she was not there? (Yes often, Yes sometimes, No)

Do you recall the circumstances in which the patient left the hospital?

Did the patient give any suggestions prior to their leaving that they did not want to stay in the hospital?

How ill was the patient when he/she left? Could you rate their health as either: Poor, Fair, Good, Very Good, or Excellent?

What were the reasons you felt he/she should have stayed in the hospital?

How many more days did you think he/she needed to be hospitalized?

How did you find out that the patient was leaving when he/she did?

What did you do when you heard he/she wished to leave?

Who was directly involved with the actual execution of the discharge?

If you were directly involved with their discharge, approximately how much time did you spend with the patient in discussing their desire to leave?

What was discussed with the patient at the time the patient wished to leave AMA?

Did the patient have new medications or a change in their medication schedule when they left the hospital? (Yes, No)

If yes, did you provide an explanation of these medications or changes? (Yes, No, No the nurse or other team member provided this information)

If yes, do you feel that you explained the purpose of the medications or changes in a way that he/she could understand? (Yes completely, Yes to some extent, No)

Did you inform your patient about possible side effects to watch for when he/she went home? (Yes completely, Yes to some extent, No)

Did you tell your patient about danger signals regarding his/her illness or treatment to watch for after he/she was discharged? (Yes completely, Yes to some extent, No)

Did the patient tell you exactly why he/she wished to leave? If so, what did he/she say?

Why do you think the patient left the hospital when he/she did?

Are you aware of any follow-up plans that were made to ensure the patient’s safety after leaving the hospital?

Do you think that he/she will return to the hospital in the next month?

Could you describe the feelings you had regarding the patient’s leaving the way he/she did?

Overall, did you feel that you treated your patient with respect and dignity? (Yes always, Yes sometimes, No)

If you could change anything that happened with the way this person left, what would you do differently?

Will you change anything in your care of patients because of this experience?

-

Have you had other patients in the hospital who wished to leave AMA? If so, were you able to convince anyone to stay? How?

* Question derived from the Picker Patient Questionnaire

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed]

- 2.Ibrahim SA, Kwoh CK, Krishnan E. Factors associated with patients who leave acute-care hospitals against medical advice. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2204–8. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Fiscella K, Meldrum S, Barnett S. Hospital discharge against advice after myocardial infarction: deaths and readmissions. Am J Med. 2007;120(12):1047–53. Dec. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hwang SW, Li J, Gupta R, Chien V, Martin RE. What happens to patients who leave hospital against medical advice? CMAJ. 2003;168(4):417–20. Feb 18. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Anis AH, Sun H, Guh DP, Palepu A, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV. Leaving hospital against medical advice among HIV-positive patients. CMAJ. 2002;167(6):633–7. Sep 17. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Fiscella K, Meldrum S, Barnett S. Hospital discharge against advice after myocardial infarction: deaths and readmissions. Am J Med. 2007;120(12):1047–53. Dec. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Seaborn Moyse H, Osmun WE. Discharges against medical advice: a community hospital’s experience. Can J Rural Med. 2004;9(4):265. Fall. [PubMed]

- 8.Aliyu ZY. Discharge against medical advice: sociodemographic, clinical and financial perspectives. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(5):325–7. Jun. [PubMed]

- 9.Weingart SN, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Patients discharged against medical advice from a general medicine service. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(8):568–71. Aug. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Moy E, Bartman BA. Race and hospital discharge against medical advice. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88(10):658–60. Oct. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Senior N, Kibbee P. Can we predict the patient who leaves against medical advice: the search for a method. Psychiatr Hosp. 1986;17(1):33–6. Winter. [PubMed]

- 12.Green P, Watts D, Poole S, Dhopesh V. Why patients sign out against medical advice (AMA): factors motivating patients to sign out AMA. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(2):489–93. May. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–15. Dec 2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication: a critical review of empirical research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:497–519. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Street RL Jr, Krupat E, Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Haidet P. Beliefs about control in the physician-patient relationship: effect on communication in medical encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):609–16. Aug. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Carrese JA. Refusal of care: patients’ well-being and physicians’ ethical obligations: “but doctor, I want to go home”. JAMA. 2006;296(6):691–5. Aug 9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1999.

- 18.Census 2000 Demographic Profiles. Available at http://www.ctnow.com/extras/census/0600900980070.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2008.

- 19.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S. The Picker patient experience questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(5):353–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition. New York: Basic Books, Inc; 1988.

- 21.Rentsch D, Luthy C, Perneger TV, Allaz AF. Hospitalisation process seen by patients and health care professionals. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(3):571–6. Aug. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Joffe S, Manocchia M, Weeks JC, Cleary PD. What do patients value in their hospital care? An empirical perspective on autonomy centred bioethics. J Med Ethics. 2003;29(2):103–8. Apr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Outcome project: enhancing residency education through outcomes assessment. Available from: http://www.acgme.org/Outcome/. Accessed May 16, 2008.

- 24.Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Learning objectives for medical student education—guidelines for medical schools: report 1 of the medical school objectives project. January 1998. Available from: http://www.aamc.org/meded/msop/. Accessed May 16, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME). Functions and structures of a medical school: standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the M.D. degree. July 2003. Available from: http://www.lcme.org/. Accessed May 16, 2008.

- 26.Evans RJ, Stanley RO, Mestrovic R, Rose L. Effects of communication skills training on students’ diagnostic efficiency. Med Educ. 1991;25:517–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Roter D, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323:908–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Roter DL, Hall JA, Katz NR. Relations between physicians’ behaviors and analogue patients’ satisfaction, recall, and impressions. Med Care. 1987;25:437–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centred consultations and outcomed in primary care: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):533–41. Nov–Dec. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Hass LJ, Leiser JP, Magill MK, Sanyer ON. Management of the difficult patient. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(10):2063–8. Nov 15. [PubMed]

- 33.AMA Principles of Medical Ethics, American Medical Association, Chicago, Illinois, 2001. http://www.cirp.org/library/statements/ama/. Accessed May 16, 2008.

- 34.Devitt PJ, Devitt AC, Dewan M. Does identifying a discharge as “against medical advice” confer legal protection? J Fam Pract. 2000;49(3):224–7. Mar. [PubMed]

- 35.Devitt PJ, Devitt AC, Dewan M. An examination of whether discharging patients against medical advice protects physicians from malpractice charges. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):899–902. Jul. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553–9. Feb 19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Virshup BB, Oppenberg AA, Coleman MM. Strategic risk management: reducing malpractice claims through more effective patient-doctor communication. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14(4):153–9. Jul–Aug. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Swota AH. Changing policy to reflect a concern for patients who sign out against medical advice. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7(3):32–4. Mar. [DOI] [PubMed]